Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Roscoe Conkling "Fatty" Arbuckle (; March 24, 1887 – June 29, 1933) was an American

In 1904,

In 1904,

Despite his physical size, Arbuckle was remarkably agile and acrobatic. Mack Sennett, when recounting his first meeting with Arbuckle, noted that he "skipped up the stairs as lightly as

Despite his physical size, Arbuckle was remarkably agile and acrobatic. Mack Sennett, when recounting his first meeting with Arbuckle, noted that he "skipped up the stairs as lightly as

At the hospital, Rappe's companion at the party, Bambina Maude Delmont, told a doctor that Arbuckle had

At the hospital, Rappe's companion at the party, Bambina Maude Delmont, told a doctor that Arbuckle had

On September 17, 1921, Arbuckle was arrested and arraigned on charges of manslaughter. He arranged

On September 17, 1921, Arbuckle was arrested and arraigned on charges of manslaughter. He arranged

The third trial began March 13, 1922, and this time the defense took no chances. McNab took an aggressive defense, completely tearing apart the prosecution's case with long and aggressive examination and cross-examination of each witness. McNab also managed to get in still more evidence about Rappe's lurid past and medical history. Another hole in the prosecution's case was opened because Prevon, a key witness, was out of the country after fleeing police custody and unable to testify. As in the first trial, Arbuckle testified as the final witness and again maintained his denials in his heartfelt testimony about his version of the events at the party. Buster Keaton is said to have been in the courtroom and provided important evidence to prove Arbuckle's innocence; Delmont was involved in prostitution, extortion, and

The third trial began March 13, 1922, and this time the defense took no chances. McNab took an aggressive defense, completely tearing apart the prosecution's case with long and aggressive examination and cross-examination of each witness. McNab also managed to get in still more evidence about Rappe's lurid past and medical history. Another hole in the prosecution's case was opened because Prevon, a key witness, was out of the country after fleeing police custody and unable to testify. As in the first trial, Arbuckle testified as the final witness and again maintained his denials in his heartfelt testimony about his version of the events at the party. Buster Keaton is said to have been in the courtroom and provided important evidence to prove Arbuckle's innocence; Delmont was involved in prostitution, extortion, and

In November 1923, Minta Durfee filed for divorce from Arbuckle, charging grounds of desertion. The divorce was granted the following January. They had been separated since 1921, though Durfee always claimed he was the nicest man in the world and they were still friends. After a brief reconciliation, Durfee again filed for divorce, this time while in

In November 1923, Minta Durfee filed for divorce from Arbuckle, charging grounds of desertion. The divorce was granted the following January. They had been separated since 1921, though Durfee always claimed he was the nicest man in the world and they were still friends. After a brief reconciliation, Durfee again filed for divorce, this time while in

Many of Arbuckle's films, including the feature '' Life of the Party'' (1920), survive only as worn prints with foreign-language inter-titles. Little or no effort was made to preserve original negatives and prints during Hollywood's first two decades. By the early 21st century, some of Arbuckle's short subjects (particularly those co-starring Chaplin or Keaton) had been restored, released on DVD, and even screened theatrically. His early influence on American

Many of Arbuckle's films, including the feature '' Life of the Party'' (1920), survive only as worn prints with foreign-language inter-titles. Little or no effort was made to preserve original negatives and prints during Hollywood's first two decades. By the early 21st century, some of Arbuckle's short subjects (particularly those co-starring Chaplin or Keaton) had been restored, released on DVD, and even screened theatrically. His early influence on American

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

In the Gumby movie entitled '' Gumby: The Movie,'' the supporting character Fatbuckle is an affectionate reference to Arbuckle. Before his death in 1997, comedian

Arbucklemania website

* * * *

Crime Library on Roscoe Arbuckle

*

Contemporary press articles pertaining to Arbuckle

Literature on Roscoe Arbuckle

Banned Film Resurfaces 90 Years After San Francisco Scandal

at

The Fatty Arbuckle Trial: The Injustice of the Century (2004)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Arbuckle, Roscoe Fatty 1887 births 1933 deaths 20th-century American comedians 20th-century American male actors 20th-century American trials American male comedians American male comedy actors American male film actors American male silent film actors Articles containing video clips False allegations of sex crimes Male actors from Kansas Manslaughter trials Paramount Pictures contract players People acquitted of manslaughter People from Smith Center, Kansas Silent film comedians Silent film directors Slapstick comedians Vaudeville performers

silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, w ...

actor, comedian, director, and screenwriter. He started at the Selig Polyscope Company

The Selig Polyscope Company was an American motion picture company that was founded in 1896 by William Selig in Chicago. The company produced hundreds of early, widely distributed commercial moving pictures, including the first films starring T ...

and eventually moved to Keystone Studios

Keystone Studios was an early film studio founded in Edendale, California (which is now a part of Echo Park) on July 4, 1912 as the Keystone Pictures Studio by Mack Sennett with backing from actor-writer Adam Kessel (1866–1946) and Charl ...

, where he worked with Mabel Normand

Amabel Ethelreid Normand (November 9, 1893 – February 23, 1930), better known as Mabel Normand, was an American silent film actress, screenwriter, director, and producer. She was a popular star and collaborator of Mack Sennett in their ...

and Harold Lloyd

Harold Clayton Lloyd, Sr. (April 20, 1893 – March 8, 1971) was an American actor, comedian, and stunt performer who appeared in many silent comedy films.Obituary '' Variety'', March 10, 1971, page 55.

One of the most influential film c ...

as well as with his nephew, Al St. John

Al St. John (also credited as Al Saint John and "Fuzzy" St. John; September 10, 1892 – January 21, 1963) was an early American motion-picture comedian. He was a nephew of silent film star Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, with whom he often performed on ...

. He also mentored Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

, Monty Banks

Montague (Monty) Banks (18 July 1897 – 7 January 1950), born Mario Bianchi, was a 20th century Italian-born American comedian, film actor, director and producer who achieved success in the UK and the United States.

Career

Banks was born Mario ...

and Bob Hope

Leslie Townes "Bob" Hope (May 29, 1903 – July 27, 2003) was a British-American comedian, vaudevillian, actor, singer and dancer. With a career that spanned nearly 80 years, Hope appeared in more than 70 short and feature films, with ...

, and brought vaudeville star Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is best known for his silent film work, in which his trademark was physical comedy accompanied by a stoic, deadpan expression ...

into the movie business. Arbuckle was one of the most popular silent stars of the 1910s and one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

, signing a contract in 1920 with Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

for $14,000 ().

Arbuckle was the defendant in three widely publicized trials between November 1921 and April 1922 for the rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

and manslaughter of actress Virginia Rappe

Virginia Caroline Rappe (; July 7, 1891 – September 9, 1921) was an American model and silent film actress. Working mostly in bit parts, Rappe died after attending a party with actor Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, who was accused of manslaughter a ...

. Rappe had fallen ill at a party hosted by Arbuckle at San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

's St. Francis Hotel

The Westin St. Francis, formerly known as St. Francis Hotel, is a hotel located on Powell and Geary Streets on Union Square, San Francisco, California. The two 12-story south wings of the hotel were built in 1904, and the double-width north wing ...

in September 1921, and died four days later. A friend of Rappe accused Arbuckle of raping and accidentally killing her. The first two trials resulted in hung juries

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again. ...

, but Keaton testified for the defense in the third trial, which acquitted Arbuckle, and the jury gave him a formal written statement of apology.

Despite Arbuckle's acquittal, the scandal has mostly overshadowed his legacy as a pioneering comedian. At the behest of Adolph Zukor

Adolph Zukor (; hu, Zukor Adolf; January 7, 1873 – June 10, 1976) was a Hungarian-American film producer best known as one of the three founders of Paramount Pictures.Obituary '' Variety'' (June 16, 1976), p. 76. He produced one of America' ...

, president of Famous Players-Lasky

Famous Players-Lasky Corporation was an American motion picture and distribution company formed on June 28, 1916, from the merger of Adolph Zukor's Famous Players Film Company—originally formed by Zukor as Famous Players in Famous Plays—and ...

, his films were banned by motion picture industry censor Will H. Hays

William Harrison Hays Sr. (; November 5, 1879 – March 7, 1954) was an American Republican politician.

As chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1918–1921, Hays managed the successful 1920 presidential campaign of Warren G. H ...

after the trial, and he was publicly ostracized. Zukor was faced with the moral outrage of various groups such as the Lord's Day Alliance, the powerful Federation of Women's Clubs

The General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890 during the Progressive Movement, is a federation of over 3,000 women's clubs in the United States which promote civic improvements through volunteer service. Many of its activities ...

and even the Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. The FTC shares jurisdiction o ...

to curb what they perceived as Hollywood debauchery run amok and its effect on the morals of the general public. While Arbuckle saw a resurgence in his popularity immediately after his third trial (in which he was acquitted) Zukor decided he had to be sacrificed to keep the movie industry out of the clutches of censors and moralists. Hays lifted the ban within a year, but Arbuckle only worked sparingly through the 1920s. Keaton made an agreement to give him thirty-five percent of his profit from Buster Keaton Comedies Co. He later worked as a film director under the pseudonym William Goodrich. He was finally able to return to acting, making short two-reel comedies in 1932–33 for Warner Bros.

Arbuckle died in his sleep of a heart attack in 1933 at age 46, reportedly on the day that he signed a contract with Warner Bros. to make a feature film.

Early life

Roscoe Arbuckle was born on March 24, 1887, in Smith Center,Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

, one of nine children of Mary E. Gordon (d. February 19, 1898) and William Goodrich Arbuckle. He weighed in excess of at birth and his father believed that he was illegitimate, as both parents had slim builds. Consequently, he named him after Senator Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, a notorious philanderer whom he despised. The birth was traumatic for Mary and resulted in chronic health problems that contributed to her death eleven years later.

Arbuckle was nearly two when his family moved to Santa Ana, California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. He first performed on stage with Frank Bacon's company at age 8 during their performance in Santa Ana. Arbuckle enjoyed performing and continued on until his mother's death in 1898, when he was 11. Arbuckle's father had always treated him harshly and now refused to support him, so he got work doing odd jobs in a hotel. He was in the habit of singing while he worked, and a professional singer heard him and invited him to perform in an amateur talent show. The show consisted of the audience judging acts by clapping or jeering, with bad acts pulled off the stage by a shepherd's crook

A shepherd's crook is a long and sturdy stick with a hook at one end, often with the point flared outwards, used by a shepherd to manage and sometimes catch sheep. In addition, the crook may aid in defending against attack by predators. Wh ...

. Arbuckle sang, danced, and did some clowning around, but he did not impress the audience. He saw the crook emerging from the wings and somersaulted into the orchestra pit in obvious panic. The audience went wild, and he won the competition and began a career in vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

.

Career

Sid Grauman

Sidney Patrick Grauman (March 17, 1879 – March 5, 1950) was an American showman who created two of Hollywood's most recognizable and visited landmarks, the Chinese Theatre and the Egyptian Theatre.

Biography

Early years

Grauman was the s ...

invited Arbuckle to sing in his new Unique Theater in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, beginning a long friendship between the two. He then joined the Pantages Theatre Group touring the West Coast and in 1906 played the Orpheum Theater in Portland, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, in a vaudeville troupe organized by Leon Errol

Leon Errol (born Leonce Errol Sims, July 3, 1881 – October 12, 1951) was an Australian-American comedian and actor in the United States, popular in the first half of the 20th century for his appearances in vaudeville, on Broadway, and in film ...

. Arbuckle became the main act and the group took their show on tour.

On August 6, 1908, Arbuckle married Minta Durfee

Araminta Estelle "Minta" Durfee (October 1, 1889 – September 9, 1975) was an American silent film actress from Los Angeles, California, possibly best known for her role in '' Mickey'' (1918).

Biography

She met Roscoe Arbuckle when he was att ...

(1889–1975), the daughter of Charles Warren Durfee and Flora Adkins. Durfee starred in many early comedy films, often with Arbuckle. They made a strange couple, as Minta was short and petite while Arbuckle tipped the scales at 300 lbs. Arbuckle then joined the Morosco Burbank Stock vaudeville company and went on a tour of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, returning in early 1909.

Arbuckle began his film career with the Selig Polyscope Company

The Selig Polyscope Company was an American motion picture company that was founded in 1896 by William Selig in Chicago. The company produced hundreds of early, widely distributed commercial moving pictures, including the first films starring T ...

in July 1909 when he appeared in ''Ben's Kid

''Ben's Kid'' is a 1909 American short comedy film featuring Fatty Arbuckle. It was Arbuckle's film debut.

Cast

* Tom Santschi (as Thomas Santschi)

* Harry Todd

* Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle (as Roscoe Arbuckle)

See also

* List of American film ...

''. He appeared sporadically in Selig one-reelers until 1913, moved briefly to Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

, and became a star in producer-director Mack Sennett

Mack Sennett (born Michael Sinnott; January 17, 1880 – November 5, 1960) was a Canadian-American film actor, director, and producer, and studio head, known as the 'King of Comedy'.

Born in Danville, Quebec, in 1880, he started in films in the ...

's ''Keystone Cops

The Keystone Cops (often spelled "Keystone Kops") are fictional, humorously incompetent policemen featured in silent film slapstick comedies produced by Mack Sennett for his Keystone Film Company between 1912 and 1917.

History

The idea for th ...

'' comedies. Although his large size was undoubtedly part of his comedic appeal, Arbuckle was self-conscious about his weight and refused to use it to get "cheap" laughs like getting stuck in a doorway or chair.

Arbuckle was a talented singer. After famed operatic tenor Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

heard him sing, he urged the comedian to "give up this nonsense you do for a living, with training you could become the second greatest singer in the world."

Screen comedian

Despite his physical size, Arbuckle was remarkably agile and acrobatic. Mack Sennett, when recounting his first meeting with Arbuckle, noted that he "skipped up the stairs as lightly as

Despite his physical size, Arbuckle was remarkably agile and acrobatic. Mack Sennett, when recounting his first meeting with Arbuckle, noted that he "skipped up the stairs as lightly as Fred Astaire

Fred Astaire (born Frederick Austerlitz; May 10, 1899 – June 22, 1987) was an American dancer, choreographer, actor, and singer. He is often called the greatest dancer in Hollywood film history.

Astaire's career in stage, film, and tele ...

" and that he "without warning went into a feather light step, clapped his hands and did a backward somersault as graceful as a girl tumbler". His comedies are noted as rollicking and fast-paced, have many chase scenes, and feature sight gag

In comedy, a visual gag or sight gag is anything which conveys its humour visually, often without words being used at all. The gag may involve a physical impossibility or an unexpected occurrence. The humor is caused by alternative interpretation ...

s. Arbuckle was fond of the " pie in the face", a comedy cliché

A cliché ( or ) is an element of an artistic work, saying, or idea that has become overused to the point of losing its original meaning or effect, even to the point of being weird or irritating, especially when at some earlier time it was consi ...

that has come to symbolize silent-film-era comedy itself. The earliest known pie thrown in film was in the June 1913 Keystone one-reeler '' A Noise from the Deep'', starring Arbuckle and frequent screen partner Mabel Normand

Amabel Ethelreid Normand (November 9, 1893 – February 23, 1930), better known as Mabel Normand, was an American silent film actress, screenwriter, director, and producer. She was a popular star and collaborator of Mack Sennett in their ...

.

In 1914, Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

made the then unheard-of offer of US$1,000 a day plus twenty-five percent of all profits and complete artistic control to make movies with Arbuckle and Normand. The movies were so lucrative and popular that in 1918 they offered Arbuckle a three-year, $3 million contract (equivalent to about $ in dollars).

By 1916, Arbuckle was experiencing serious health problems. An infection that developed on his leg became a carbuncle

A carbuncle is a cluster of boils caused by bacterial infection, most commonly with ''Staphylococcus aureus'' or ''Streptococcus pyogenes''. The presence of a carbuncle is a sign that the immune system is active and fighting the infection. The ...

so severe that doctors considered amputation. Although Arbuckle was able to keep his leg, he was prescribed morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies ('' Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a pain medication, and is also commonly used recreationally, or to make other illicit opioids. T ...

against the pain; he would later be accused of being addicted to it. Following his recovery, Arbuckle started his own film company, Comique, in partnership with Joseph Schenck

Joseph Michael Schenck (; December 25, 1876 – October 22, 1961) was a Russian-born American film studio executive.

Life and career

Schenck was born to a Jewish family in Rybinsk, Yaroslavl Oblast, Russian Empire. He emigrated to New York ...

. Although Comique produced some of the best short pictures of the silent era, Arbuckle transferred his controlling interest in the company to Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is best known for his silent film work, in which his trademark was physical comedy accompanied by a stoic, deadpan expression ...

in 1918 and accepted Paramount's $3 million offer to make up to 18 feature films over three years.

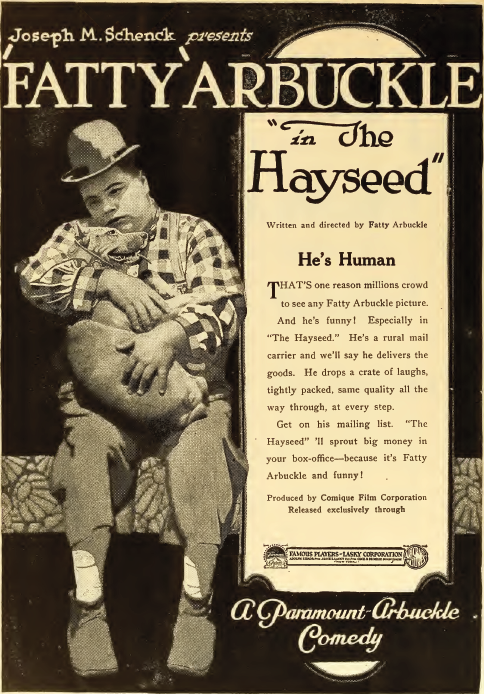

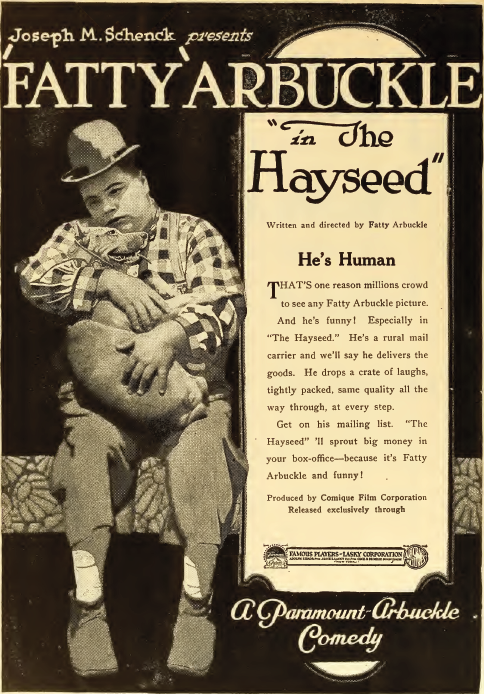

Arbuckle disliked his screen nickname. "Fatty" had also been Arbuckle's nickname since school; "It was inevitable", he said. Fans also called Roscoe "The Prince of Whales" and "The Balloonatic". However, the name ''Fatty'' identifies the character that Arbuckle portrayed on-screen (usually a naive hayseed), not Arbuckle himself. When Arbuckle portrayed a female, the character was named "Miss Fatty", as in the film '' Miss Fatty's Seaside Lovers''. Arbuckle discouraged anyone from addressing him as "Fatty" off-screen, and when they did so his usual response was, "I've got a name, you know."

Scandal

On September 5, 1921, Arbuckle took a break from his hectic film schedule and, despite suffering from second-degree burns to both buttocks from an on-set accident, drove to San Francisco with two friends, Lowell Sherman andFred Fishback

Fred C. Fishback (born Moscu Fischback; January 18, 1894January 6, 1925) was a film director, actor, screenwriter, and producer of the silent era. Following the 1921 scandal surrounding Roscoe Arbuckle, in which he was involved, Fishback worked ...

. The three checked into three rooms at the St. Francis Hotel

The Westin St. Francis, formerly known as St. Francis Hotel, is a hotel located on Powell and Geary Streets on Union Square, San Francisco, California. The two 12-story south wings of the hotel were built in 1904, and the double-width north wing ...

: 1219 for Arbuckle and Fishback to share, 1221 for Sherman, and 1220 designated as a party room. Several women were invited to the suite. During the carousing, a 30-year-old aspiring actress named Virginia Rappe

Virginia Caroline Rappe (; July 7, 1891 – September 9, 1921) was an American model and silent film actress. Working mostly in bit parts, Rappe died after attending a party with actor Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, who was accused of manslaughter a ...

was found seriously ill in room 1219 and was examined by the hotel doctor, who concluded her symptoms were mostly caused by intoxication and gave her morphine to calm her. Rappe was not hospitalized until two days after the incident.

At the hospital, Rappe's companion at the party, Bambina Maude Delmont, told a doctor that Arbuckle had

At the hospital, Rappe's companion at the party, Bambina Maude Delmont, told a doctor that Arbuckle had rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

d her friend. The doctor examined Rappe but found no evidence of rape. She died one day after her hospitalization from peritonitis

Peritonitis is inflammation of the localized or generalized peritoneum, the lining of the inner wall of the abdomen and cover of the abdominal organs. Symptoms may include severe pain, swelling of the abdomen, fever, or weight loss. One part o ...

caused by a ruptured bladder

Urinary bladder disease includes urinary bladder inflammation such as cystitis, bladder rupture and bladder obstruction (tamponade). Cystitis is common, sometimes referred to as urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by bacteria, bladder rupture occ ...

. Rappe suffered from chronic urinary tract infection

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects part of the urinary tract. When it affects the lower urinary tract it is known as a bladder infection (cystitis) and when it affects the upper urinary tract it is known as a kidne ...

s, a condition that liquor irritated dramatically.

Delmont then told police that Arbuckle had raped Rappe; the police concluded that the impact of Arbuckle's overweight body lying on top of Rappe had eventually caused her bladder to rupture. At a later press conference, Rappe's manager, Al Semnacher, accused Arbuckle of using a piece of ice to simulate sex with Rappe, thus leading to her injuries. By the time the story was reported in newspapers, the object had evolved into a Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a carbonated soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. Originally marketed as a temperance bar, temperance drink and intended as a patent medicine, it was invented in the late 19th century by John Stith Pembe ...

or champagne bottle rather than a piece of ice. In fact, witnesses testified that Arbuckle rubbed the ice on Rappe's stomach to ease her abdominal pain. Arbuckle denied any wrongdoing. Delmont later made a statement incriminating Arbuckle to the police in an attempt to extort

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, al ...

money from Arbuckle's attorneys.

Arbuckle's trial was a major media event. The story was fueled by yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

, with the newspapers portraying Arbuckle as a gross lecher who used his weight to overpower innocent girls. William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

's nationwide newspaper chain exploited the situation with exaggerated and sensationalized

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emotion ...

stories. Hearst was gratified by the profits he accrued during the Arbuckle scandal, and he later said that it had "sold more newspapers than any event since the sinking of the ''Lusitania''." Morality groups called for Arbuckle to be sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. The resulting scandal destroyed Arbuckle's career along with his personal life.

Arbuckle was regarded by those who knew him closely as a good-natured man who was shy around women; he has been described as "the most chaste man in pictures". However, studio executives, fearing negative publicity by association, ordered Arbuckle's industry friends and fellow actors (whose careers they controlled) not to publicly speak up for him. Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

, who was in Britain at the time, told reporters that he could not and would not believe Arbuckle had anything to do with Rappe's death; having known Arbuckle since they both worked at Keystone in 1914, Chaplin "knew Roscoe to be a genial, easy-going type who would not harm a fly." Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is best known for his silent film work, in which his trademark was physical comedy accompanied by a stoic, deadpan expression ...

reportedly did make one public statement in support of Arbuckle's innocence, a decision which earned him a mild reprimand from the studio where he worked. Film actor William S. Hart, who had never met or worked with Arbuckle, made a number of damaging public statements in which he presumed that Arbuckle was guilty. Arbuckle later wrote a premise for a film parodying Hart as a thief, bully, and wife beater, which Keaton purchased from him. The resulting film, ''The Frozen North

''The Frozen North'' is a 1922 American short comedy film directed by and starring Buster Keaton. The film is a parody of early western films, especially those of William S. Hart. The film was written by Keaton and Edward F. Cline (credited ...

'', was released in 1922, almost a year after the scandal first emerged. Keaton co-wrote, directed and starred in the picture; consequently, Hart refused to speak to Keaton for many years.

Trials

The prosecutor, San Francisco District AttorneyMatthew Brady

Matthew Brady (1799 – 4 May 1826) was an English-born convict who became a bushranger in Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania). He was sometimes known as "Gentleman Brady" due to his good treatment and fine manners when robbing his victims ...

, an intensely ambitious man who planned to run for governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, made public pronouncements of Arbuckle's guilt and pressured witnesses to make false statements. Brady at first used Delmont as his star witness during the indictment hearing. The defense

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indus ...

had also obtained a letter from Delmont admitting to a plan to extort payment from Arbuckle. In view of Delmont's constantly changing story, her testimony would have ended any chance of going to trial. Ultimately, the judge found no evidence of rape. After hearing testimony from one of the party guests, Zey Prevon, that Rappe told her "Roscoe hurt me" on her deathbed, the judge decided that Arbuckle could be charged with first-degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially t ...

. Brady had originally planned to seek the death penalty. The charge was later reduced to manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

.

First trial

On September 17, 1921, Arbuckle was arrested and arraigned on charges of manslaughter. He arranged

On September 17, 1921, Arbuckle was arrested and arraigned on charges of manslaughter. He arranged bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

after nearly three weeks in jail. The trial began November 14, 1921, in the city courthouse in San Francisco. Arbuckle hired as his lead defense counsel Gavin McNab, a competent local attorney. The principal witness was Prevon. At the beginning of the trial Arbuckle told his already-estranged wife, Minta Durfee, that he did not harm Rappe; she believed him and appeared regularly in the courtroom to support him. Public feeling was so negative that Durfee was later shot at while entering the courthouse.

Brady's first witnesses during the trial included Betty Campbell, a model, who attended the party and testified that she saw Arbuckle with a smile on his face hours after the alleged rape occurred; Grace Hultson, a local hospital nurse who testified it was very likely that Arbuckle raped Rappe and bruised her body in the process; and Dr. Edward Heinrich, a local criminologist

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and ...

who claimed that the fingerprints on the door to the hallway proved that Rappe had tried to flee, but that Arbuckle had stopped her by putting his hand over hers. Dr. Arthur Beardslee, the hotel doctor who had examined Rappe, testified that an external force seemed to have damaged the bladder. During cross-examination, however, Campbell revealed that Brady had threatened to charge her with perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

if she did not testify against Arbuckle. Dr. Heinrich's claim to have found fingerprints was cast into doubt after McNab produced a maid from the St. Francis Hotel who testified that she had thoroughly cleaned the room before the investigation took place. Dr. Beardslee admitted that Rappe had never mentioned being assaulted while he was treating her. McNab was furthermore able to get Nurse Hultson to admit that the rupture of Rappe's bladder could very well have been a result of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

, and that the bruises on her body could also have been a result of the heavy jewelry she was wearing that evening.

On November 28, Arbuckle testified as the defense's final witness. He was simple, direct, and unflustered in both direct and cross-examination. In his testimony, Arbuckle claimed that Rappe (whom he testified he had known for five or six years) came into the party room (1220) around noon that day, and that sometime afterward he went to his room (1219) to change clothes after Mae Taub, daughter-in-law of Billy Sunday

William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (November 19, 1862 – November 6, 1935) was an American outfielder in baseball's National League and widely considered the most influential American evangelist during the first two decades of the 20th century.

Bo ...

, asked him for a ride into town. In his room, Arbuckle discovered Rappe in the bathroom vomiting into the toilet. He then claimed Rappe told him she felt ill and asked to lie down, and that he carried her into the bedroom and asked a few of the party guests to help treat her. When Arbuckle and a few of the guests re-entered the room, they found Rappe on the floor near the bed tearing at her clothing and going into violent convulsions. To calm Rappe down, they placed her in a bathtub of cool water. Arbuckle and Fischbach then took her to room 1227 and called the hotel manager and doctor. At this point all those present thought Rappe was just very drunk, including the hotel doctors. Probably assuming Rappe would simply sleep it off, Arbuckle drove Taub into town.

During the whole trial, the prosecution presented medical descriptions of Rappe's bladder as evidence that she had an illness. In his testimony, Arbuckle denied he had any knowledge of Rappe's illness. During cross-examination, Assistant District Attorney Leo Friedman aggressively grilled Arbuckle over the fact that he refused to call a doctor when he found Rappe sick, and argued that he refused to do so because he knew of Rappe's illness and saw a perfect opportunity to rape and kill her. Arbuckle calmly maintained that he never physically hurt or sexually assaulted Rappe in any way during the party, and he also stated that he never made any inappropriate sexual advances against any woman in his life. After over two weeks of testimony with sixty prosecution and defense witnesses, including eighteen doctors who testified about Rappe's illness, the defense rested. On December 4, 1921, the jury returned five days later deadlocked after nearly forty-four hours of deliberation with a 10–2 not guilty verdict, and a mistrial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

was declared.

Arbuckle's attorneys later concentrated their attention on one woman named Helen Hubbard, who had told jurors that she would vote guilty "until hell freezes over". She refused to look at the exhibits or read the trial transcripts, having made up her mind in the courtroom. Hubbard's husband was a lawyer who did business with the D.A.'s office, and expressed surprise that she was not challenged when selected for the jury pool. While much attention was paid to Hubbard after the trial, some former jury members told reporters that they believed that Arbuckle was indeed guilty, but not beyond a reasonable doubt

Beyond a reasonable doubt is a legal standard of proof required to validate a criminal conviction in most adversarial legal systems. It is a higher standard of proof than the balance of probabilities standard commonly used in civil cases, bec ...

. During the deliberations, some jurors joined Hubbard in voting to convict, but they all recanted except for Thomas Kilkenny. Arbuckle researcher Joan Myers describes the political climate and the media attention to the presence of women on juries (which had only been legal for four years at the time) and how Arbuckle's defense immediately singled out Hubbard as a villain; Myers also records Hubbard's account of the jury foreman August Fritze's attempts to bully her into changing her vote to 'not guilty'. While Hubbard offered explanations on her vote whenever challenged, Kilkenny remained silent and quickly faded from the media spotlight after the trial ended.

Second trial

The second trial began January 11, 1922, with a new jury, but with the same legal defense and prosecution as well as the same presiding judge. The same evidence was presented, but this time one of the witnesses, Zey Prevon, testified that Brady had forced her to lie. Another witness who testified during the first trial, a former Culver Studios security guard named Jesse Norgard, testified that Arbuckle had once shown up at the studio and offered him a cashbribe

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corru ...

in exchange for the key to Rappe's dressing room. The comedian supposedly said he wanted it to play a joke on the actress. Norgard said he refused to give him the key. During cross-examination, Norgard's testimony was called into question when he was revealed to be an ex-convict who was currently charged with sexually assaulting

Sexual assault is an act in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexual violence, which ...

an eight-year-old girl, and who was also looking for a sentence reduction from Brady in exchange for his testimony. Further, in contrast to the first trial, Rappe's history of promiscuity

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by ma ...

and heavy drinking was detailed. The second trial also discredited some major evidence such as the identification of Arbuckle's fingerprints on the hotel bedroom door: Heinrich took back his earlier testimony from the first trial and testified that the fingerprint evidence was likely faked. The defense was so convinced of an acquittal that Arbuckle was not called to testify. His lawyer, McNab, made no closing argument to the jury. However, some jurors interpreted the refusal to let Arbuckle testify as a sign of guilt. After five days and over forty hours of deliberation, the jury returned on February 3, deadlocked with a 10–2 majority in favour of conviction, resulting in another mistrial.

Third trial

By the time of Arbuckle's third trial, his films had been banned, and newspapers had been filled for the past seven months with stories of Hollywood orgies, murder, and sexual perversion. Delmont was touring the country giving one-woman shows as, "The woman who signed the murder charge against Arbuckle", and lecturing on the evils of Hollywood. The third trial began March 13, 1922, and this time the defense took no chances. McNab took an aggressive defense, completely tearing apart the prosecution's case with long and aggressive examination and cross-examination of each witness. McNab also managed to get in still more evidence about Rappe's lurid past and medical history. Another hole in the prosecution's case was opened because Prevon, a key witness, was out of the country after fleeing police custody and unable to testify. As in the first trial, Arbuckle testified as the final witness and again maintained his denials in his heartfelt testimony about his version of the events at the party. Buster Keaton is said to have been in the courtroom and provided important evidence to prove Arbuckle's innocence; Delmont was involved in prostitution, extortion, and

The third trial began March 13, 1922, and this time the defense took no chances. McNab took an aggressive defense, completely tearing apart the prosecution's case with long and aggressive examination and cross-examination of each witness. McNab also managed to get in still more evidence about Rappe's lurid past and medical history. Another hole in the prosecution's case was opened because Prevon, a key witness, was out of the country after fleeing police custody and unable to testify. As in the first trial, Arbuckle testified as the final witness and again maintained his denials in his heartfelt testimony about his version of the events at the party. Buster Keaton is said to have been in the courtroom and provided important evidence to prove Arbuckle's innocence; Delmont was involved in prostitution, extortion, and blackmail

Blackmail is an act of coercion using the threat of revealing or publicizing either substantially true or false information about a person or people unless certain demands are met. It is often damaging information, and it may be revealed to fa ...

. During closing statements, McNab reviewed how flawed the case was against Arbuckle from the very start and how Brady fell for the outlandish charges of Delmont, whom McNab described as "the complaining witness who never witnessed". The jury began deliberations April 12 and took only six minutes to return with a unanimous not-guilty verdict; five of those minutes were spent writing a formal statement of apology to Arbuckle for putting him through the ordeal, a dramatic move in American justice. The jury statement as read by the jury foreman stated:

After the reading of the apology statement, the jury foreman personally handed the statement to Arbuckle, who kept it as a treasured memento for the rest of his life. Then, one by one, the 12-person jury plus the two jury alternates walked up to Arbuckle's defense table, where they shook his hand and/or embraced and personally apologized to him. The entire jury proudly posed with Arbuckle for photographers after the verdict and apology.

Some experts later concluded that Rappe's bladder might also have ruptured as a result of an abortion she might have had a short time before the fateful party. Her organs had been destroyed and it was now impossible to test for pregnancy. Because alcohol was consumed at the party, Arbuckle was forced to plead guilty to one count of violating the Volstead Act

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was an act of the 66th United States Congress, designed to carry out the intent of the 18th Amendment (ratified January 1919), which established the prohibition of alcoholic d ...

and had to pay a $500 fine. At the time of his acquittal, he owed over $700,000 (equivalent to approximately $ in dollars) in legal fees to his attorneys for the three criminal trials, and he was forced to sell his house and all of his cars to pay some of the debt.

The scandal and trials had greatly damaged Arbuckle's popularity among the general public. In spite of the acquittal and the apology, his reputation was not restored and the effects of the scandal continued. Will H. Hays

William Harrison Hays Sr. (; November 5, 1879 – March 7, 1954) was an American Republican politician.

As chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1918–1921, Hays managed the successful 1920 presidential campaign of Warren G. H ...

, who served as the head of the newly formed Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) censor board, cited Arbuckle as an example of the poor morals in Hollywood. On April 18, 1922, six days after Arbuckle's acquittal, Hays banned him from ever working in U.S. movies again. He had also requested that all showings and bookings of Arbuckle films be canceled, and exhibitors complied. In December of the same year, under public pressure, Hays elected to lift the ban. However, Arbuckle was still unable to secure work as an actor.

Most exhibitors still declined to show Arbuckle's films, several of which now have no copies known to have survived intact. One of Arbuckle's feature-length films known to survive is ''Leap Year

A leap year (also known as an intercalary year or bissextile year) is a calendar year that contains an additional day (or, in the case of a lunisolar calendar, a month) added to keep the calendar year synchronized with the astronomical year or ...

'', which Paramount declined to release in the U.S. owing to the scandal. It was eventually released in Europe. With Arbuckle's films now banned, in March 1922 Keaton signed an agreement to give Arbuckle thirty-five percent of all future profits from his production company, Buster Keaton Comedies, in hopes of easing his financial situation.

Aftermath

In November 1923, Minta Durfee filed for divorce from Arbuckle, charging grounds of desertion. The divorce was granted the following January. They had been separated since 1921, though Durfee always claimed he was the nicest man in the world and they were still friends. After a brief reconciliation, Durfee again filed for divorce, this time while in

In November 1923, Minta Durfee filed for divorce from Arbuckle, charging grounds of desertion. The divorce was granted the following January. They had been separated since 1921, though Durfee always claimed he was the nicest man in the world and they were still friends. After a brief reconciliation, Durfee again filed for divorce, this time while in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, in December 1924. Arbuckle married Doris Deane

Doris Anita Dibble (January 20, 1901 – March 24, 1974) was an actress who appeared in films. She supported Al St. John in comedy roles.

Early life

Deane was born in 1901 in Wisconsin.

Marriage to Roscoe Arbuckle

She married film director ...

on May 16, 1925.

Arbuckle tried returning to filmmaking, but industry resistance to distributing his pictures continued to linger after his acquittal. He retreated into alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

. In the words of his first wife, "Roscoe only seemed to find solace and comfort in a bottle". Keaton attempted to help Arbuckle by giving him work on his films. Arbuckle wrote the story for a Keaton short called '' Day Dreams'' (1922). Arbuckle allegedly co-directed scenes in Keaton's '' Sherlock Jr.'' (1924), but it is unclear how much of this footage remained in the film's final cut. In 1925, Carter DeHaven

Carter DeHaven (born Francis O'Callaghan; October 5, 1886 – July 20, 1977) was an American film and stage actor, film director, and screenwriter.

Career

DeHaven started his career in vaudeville in 1896 and started acting in movies in 1915. H ...

's short ''Character Studies'', shot before the scandal, was released. Arbuckle appeared alongside Keaton, Harold Lloyd

Harold Clayton Lloyd, Sr. (April 20, 1893 – March 8, 1971) was an American actor, comedian, and stunt performer who appeared in many silent comedy films.Obituary '' Variety'', March 10, 1971, page 55.

One of the most influential film c ...

, Rudolph Valentino

Rodolfo Pietro Filiberto Raffaello Guglielmi di Valentina d'Antonguolla (May 6, 1895 – August 23, 1926), known professionally as Rudolph Valentino and nicknamed The Latin Lover, was an Italian actor based in the United States who starred ...

, Douglas Fairbanks

Douglas Elton Fairbanks Sr. (born Douglas Elton Thomas Ullman; May 23, 1883 – December 12, 1939) was an American actor, screenwriter, director, and producer. He was best known for his swashbuckling roles in silent films including '' The Thi ...

, and Jackie Coogan

John Leslie Coogan (October 26, 1914 – March 1, 1984) was an American actor and comedian who began his film career as a child actor in silent films.

Charlie Chaplin's film classic '' The Kid'' (1921) made him one of the first child stars in t ...

. The same year, in ''Photoplay

''Photoplay'' was one of the first American film (another name for ''photoplay'') fan magazines. It was founded in 1911 in Chicago, the same year that J. Stuart Blackton founded '' Motion Picture Story,'' a magazine also directed at fans. For mo ...

''s August issue, James R. Quirk

James R. Quirk (September 4, 1884 – August 1, 1932) was an American magazine editor.

Career

Quirk was the vice president and editor of ''Photoplay'' magazine, one of the earliest film or fan glamour magazines and particularly popular in th ...

wrote: "I would like to see Roscoe Arbuckle make a comeback to the screen." He also said: "The American nation prides itself upon its spirit of fair play. We like the whole world to look upon America as the place where every man gets a square deal. Are you sure Roscoe Arbuckle is getting one today? I'm not."

William Goodrich pseudonym

Eventually, Arbuckle worked as a director under thepseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

"William Goodrich". Author David Yallop

David Anthony Yallop (27 January 1937 – 23 August 2018) was a British author who wrote chiefly about unsolved crimes. In the 1970s, he contributed scripts for a number of BBC comedy shows. In the same decade he also wrote 10 episodes for the I ...

cites Arbuckle's father's full name as William Goodrich Arbuckle as the inspiration behind the alias. Another tale credits Keaton, an inveterate pun

A pun, also known as paronomasia, is a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. These ambiguities can arise from the intentional use of homophoni ...

ster, with suggesting that Arbuckle become a director under the alias "Will B. Good". The pun being too obvious, Arbuckle adopted the more formal pseudonym "William Goodrich". Keaton himself told this story during a recorded interview with Kevin Brownlow

Kevin Brownlow (born Robert Kevin Brownlow; 2 June 1938) is a British film historian, television documentary-maker, filmmaker, author, and film editor. He is best known for his work documenting the history of the silent era, having become inte ...

in the 1960s.

Between 1924 and 1932, Arbuckle directed a number of comedy shorts under the pseudonym for Educational Pictures

Educational Pictures, also known as Educational Film Exchanges, Inc. or Educational Films Corporation of America, was an American film production and film distribution company founded in 1916 by Earle (E. W.) Hammons (1882–1962). Educational pr ...

, which featured lesser-known comics of the day. Louise Brooks

Mary Louise Brooks (November 14, 1906 – August 8, 1985) was an American film actress and dancer during the 1920s and 1930s. She is regarded today as an icon of the Jazz Age and flapper culture, in part due to the bob hairstyle that she helpe ...

, who played the ingenue in '' Windy Riley Goes Hollywood'' (1931), told Brownlow of her experiences in working with Arbuckle:

He made no attempt to direct this picture. He just sat in his director's chair like a dead man. He had been very nice and sweetly dead ever since the scandal that ruined his career. But it was such an amazing thing for me to come in to make this broken-down picture, and to find my director was the great Roscoe Arbuckle. Oh, I thought he was magnificent in films. He was a wonderful dancer—a wonderful ballroom dancer, in his heyday. It was like floating in the arms of a huge doughnut—really delightful.Among the more visible directorial projects under the Goodrich pseudonym was the

Eddie Cantor

Eddie Cantor (born Isidore Itzkowitz; January 31, 1892 – October 10, 1964) was an American comedian, actor, dancer, singer, songwriter, film producer, screenwriter and author. Familiar to Broadway, radio, movie, and early television audiences ...

feature '' Special Delivery'' (1927), which was released by Paramount and co-starred William Powell

William Horatio Powell (July 29, 1892 – March 5, 1984) was an American actor. A major star at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, he was paired with Myrna Loy in 14 films, including the '' Thin Man'' series based on the Nick and Nora Charles characters cr ...

and Jobyna Ralston

Jobyna Ralston (born Jobyna Lancaster Raulston, November 21, 1899 – January 22, 1967) was an American stage and film actress. She had a featured role in ''Wings'' in 1927, but is perhaps best remembered today for her on-screen chemistry with H ...

. His highest-profile project was arguably ''The Red Mill

''The Red Mill'' is an operetta written by Victor Herbert, with a libretto by Henry Blossom. The farcical story concerns two American vaudevillians who wreak havoc at an inn in Holland, interfering with two marriages; but all ends well. The musica ...

'', also released in 1927, a Marion Davies

Marion Davies (born Marion Cecilia Douras; January 3, 1897 – September 22, 1961) was an American actress, producer, screenwriter, and philanthropist. Educated in a religious convent, Davies fled the school to pursue a career as a chorus girl ...

vehicle.

Roscoe Arbuckle’s Plantation Café

Arbuckle and Dan Coombs, one of Culver City's first mayors, re-opened the Plantation Club near theMetro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

studios on Washington Boulevard as Roscoe Arbuckle's Plantation Café on August 2, 1928. By 1930, Arbuckle sold his interest and it became known as George Olsen's Plantation Café, later The Plantation Trailer Court and then Foreman Phillips County Barn Dance.

Second divorce and third marriage

In 1929, Doris Deane sued for divorce from Arbuckle inLos Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, charging desertion and cruelty. On June 21, 1932, Roscoe married Addie Oakley Dukes McPhail (later Addie Oakley Sheldon, 1905–2003) in Erie, Pennsylvania

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 ...

.Oderman 2005 p.212

Brief comeback and death

In 1932, Arbuckle signed a contract with Warner Bros. to star under his own name in a series of six two-reel comedies, to be filmed at theVitaphone

Vitaphone was a sound film system used for feature films and nearly 1,000 short subjects made by Warner Bros. and its sister studio First National from 1926 to 1931. Vitaphone was the last major analog sound-on-disc system and the only one ...

studios in Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

. These six short films constitute the only recordings of Arbuckle's voice. Silent-film comedian Al St. John

Al St. John (also credited as Al Saint John and "Fuzzy" St. John; September 10, 1892 – January 21, 1963) was an early American motion-picture comedian. He was a nephew of silent film star Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, with whom he often performed on ...

(Arbuckle's nephew) and actors Lionel Stander

Lionel Jay Stander (January 11, 1908 – November 30, 1994) was an American actor in films, radio, theater and television. He is best remembered for his role as majordomo Max on the 1980s mystery television series '' Hart to Hart''.

Early ...

and Shemp Howard

Samuel Horwitz (March 11, 1895 – November 22, 1955), known professionally as Shemp Howard, was an American actor and comedian. He was called "Shemp" because "Sam" came out that way in his mother's thick Litvak accent.

He is best known as the ...

appeared with Arbuckle. One of the films ('' How've You Bean?'') had grocery-store gags reminiscent of Arbuckle's 1917 short '' The Butcher Boy'', with vaudeville comic Fritz Hubert as his assistant, dressed like Buster Keaton. The Vitaphone shorts were very successful in America, although when Warner Bros. attempted to release the first one (''Hey, Pop!

''Hey, Pop!'' is a 1932 American pre-Code comedy film starring Fatty Arbuckle, and the first under Arbuckle's new contract with Warner Brothers.

Cast

* Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle as Fatty the Chef

* Billy Heyes as Bill

* Connie Almy as Landlady

...

'') in the United Kingdom, the British Board of Film Censors

The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC, previously the British Board of Film Censors) is a non-governmental organization, non-governmental organisation founded by the British film industry in 1912 and responsible for the national clas ...

cited the ten-year-old scandal and refused to grant an exhibition certificate.

On June 28, 1933, Arbuckle had finished filming the last of the two-reelers (four of which had already been released). The next day he signed a contract with Warner Bros. to star in a feature-length film. That night he went out with friends to celebrate his first wedding anniversary and the new Warner Bros. contract when he reportedly said: "This is the best day of my life." He suffered a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

later that night and died in his sleep. He was 46. His widow Addie requested that his body be cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre ...

, as that was Arbuckle's wish.

Legacy

Many of Arbuckle's films, including the feature '' Life of the Party'' (1920), survive only as worn prints with foreign-language inter-titles. Little or no effort was made to preserve original negatives and prints during Hollywood's first two decades. By the early 21st century, some of Arbuckle's short subjects (particularly those co-starring Chaplin or Keaton) had been restored, released on DVD, and even screened theatrically. His early influence on American

Many of Arbuckle's films, including the feature '' Life of the Party'' (1920), survive only as worn prints with foreign-language inter-titles. Little or no effort was made to preserve original negatives and prints during Hollywood's first two decades. By the early 21st century, some of Arbuckle's short subjects (particularly those co-starring Chaplin or Keaton) had been restored, released on DVD, and even screened theatrically. His early influence on American slapstick

Slapstick is a style of humor involving exaggerated physical activity that exceeds the boundaries of normal physical comedy. Slapstick may involve both intentional violence and violence by mishap, often resulting from inept use of props such ...

comedy is widely recognised.

For his contributions to the film industry, in 1960, some 27 years after his death, Arbuckle was awarded a star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Calif ...

located at 6701 Hollywood Boulevard

Hollywood Boulevard is a major east–west street in Los Angeles, California. It begins in the east at Sunset Boulevard in the Los Feliz district and proceeds to the west as a major thoroughfare through Little Armenia and Thai Town, Hollywoo ...

.

In popular culture

Neil Sedaka

Neil Sedaka (; born March 13, 1939) is an American singer-songwriter and pianist. Since his music career began in 1957, he has sold millions of records worldwide and has written or co-written over 500 songs for himself and other artists, collabo ...

references Arbuckle, along with Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

, Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is best known for his silent film work, in which his trademark was physical comedy accompanied by a stoic, deadpan expression ...

, Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel (born Arthur Stanley Jefferson; 16 June 1890 – 23 February 1965) was an English comic actor, writer, and film director who was one half of the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy. He appeared with his comedy partner Oliver Hardy in 10 ...

, and Oliver Hardy

Oliver Norvell Hardy (born Norvell Hardy; January 18, 1892 – August 7, 1957) was an American comic actor and one half of Laurel and Hardy, the double act that began in the era of silent films and lasted from 1926 to 1957. He appeared with his ...

in his 1971 song "Silent Movies", as heard on his ''Emergence

In philosophy, systems theory, science, and art, emergence occurs when an entity is observed to have properties its parts do not have on their own, properties or behaviors that emerge only when the parts interact in a wider whole.

Emergenc ...

'' album.

The James Ivory

James Francis Ivory (born June 7, 1928) is an American film director, producer, and screenwriter. For many years, he worked extensively with Indian-born film producer Ismail Merchant, his domestic as well as professional partner, and with scree ...

film '' The Wild Party'' (1975) has been repeatedly but incorrectly cited as a film dramatization of the Arbuckle–Rappe scandal. In fact it is loosely based on the 1926 poem by Joseph Moncure March

Joseph Moncure March (July 27, 1899 New York City - February 14, 1977 Los Angeles, California) was an American poet and essayist, best known for his long narrative poems '' The Wild Party'' and '' The Set-Up''.

Life

After serving in World Wa ...

. In this film, James Coco portrays a heavy-set silent film comedian named Jolly Grimm whose career is on the skids, but who is desperately planning a comeback. Raquel Welch

Jo Raquel Welch ( Tejada; September 5, 1940) is an American actress.

She first won attention for her role in '' Fantastic Voyage'' (1966), after which she won a contract with 20th Century Fox. They lent her contract to the British studio Hamm ...

portrays his mistress, who ultimately goads him into shooting her. This film was loosely based on the misconceptions surrounding the Arbuckle scandal, yet it bears almost no resemblance to the documented facts of the case.

In Ken Russell

Henry Kenneth Alfred Russell (3 July 1927 – 27 November 2011) was a British film director, known for his pioneering work in television and film and for his flamboyant and controversial style. His films in the main were liberal adaptation ...

's 1977 biopic '' Valentino'', Rudolph Nureyev

Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev ( ; Tatar/ Bashkir: Рудольф Хәмит улы Нуриев; rus, Рудо́льф Хаме́тович Нуре́ев, p=rʊˈdolʲf xɐˈmʲetəvʲɪtɕ nʊˈrʲejɪf; 17 March 19386 January 1993) was a Soviet ...

as a pre-movie star Rudolph Valentino

Rodolfo Pietro Filiberto Raffaello Guglielmi di Valentina d'Antonguolla (May 6, 1895 – August 23, 1926), known professionally as Rudolph Valentino and nicknamed The Latin Lover, was an Italian actor based in the United States who starred ...

dances in a nightclub before a grossly overweight, obnoxious, and hedonistic celebrity called "Mr. Fatty" (played by William Hootkins

William Michael "Hoot"Austin Mutti-MewseObituary: William Hootkins ''The Guardian'', November 14, 2005, accessed December 13, 2012. Hootkins (July 5, 1948 – October 23, 2005) was an American actor, best known for supporting roles in Hollywood b ...

), a caricature of Arbuckle rooted in the public view of him created in popular press coverage of the Rappe rape trial. In the scene, Valentino picks up starlet Jean Acker (played by Carol Kane

Carolyn Laurie Kane (born June 18, 1952) is an American actress. She became known in the 1970s and 1980s in films such as '' Hester Street'' (for which she received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress), '' Dog Day Afternoon'', ''Annie ...

) off a table in which she is sitting in front of Fatty and dances with her, enraging the spoiled star, who becomes apoplectic.Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

In the Gumby movie entitled '' Gumby: The Movie,'' the supporting character Fatbuckle is an affectionate reference to Arbuckle. Before his death in 1997, comedian

Chris Farley

Christopher Crosby Farley (February 15, 1964 – December 18, 1997) was an American actor and comedian. Farley was known for his loud, energetic comedic style, and was a member of Chicago's Second City Theatre and later a cast member of the ...

expressed interest in starring as Arbuckle in a biography film. According to the 2008 biography ''The Chris Farley Show: A Biography in Three Acts'', Farley and screenwriter David Mamet

David Alan Mamet (; born November 30, 1947) is an American playwright, filmmaker, and author. He won a Pulitzer Prize and received Tony nominations for his plays ''Glengarry Glen Ross'' (1984) and '' Speed-the-Plow'' (1988). He first gained cri ...

agreed to work together on what would have been Farley's first dramatic role. In 2007, director Kevin Connor planned a film, ''The Life of the Party'', based on Arbuckle's life. It was to star Chris Kattan

Christopher Lee Kattan () (born October 19, 1970) is an American actor and comedian. He was a cast member on ''Saturday Night Live'' from 1996 to 2003. He played Doug Butabi in ''A Night at the Roxbury'', Bob on the first four seasons of '' The M ...

and Preston Lacy. However, the project was shelved. Like Farley, comedians John Belushi

John Adam Belushi (January 24, 1949 – March 5, 1982) was an American comedian, actor, and musician, best known for being one of the seven original cast members of the NBC sketch comedy show ''Saturday Night Live'' (''SNL''). Throughout his c ...

and John Candy

John Franklin Candy (October 31, 1950 – March 4, 1994) was a Canadian actor and comedian known mainly for his work in Hollywood films. Candy rose to fame in the 1970s as a member of the Toronto branch of the Second City and its '' SCTV'' seri ...

also considered playing Arbuckle, but each of them died before a biopic was made. Farley's film was signed with Vince Vaughn as his co-star.

In April and May 2006, the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of t ...

in New York City mounted a 56-film, month-long retrospective of all of Arbuckle's known surviving work, running the entire series twice.

Arbuckle is the subject of a 2004 novel titled '' I, Fatty'' by author Jerry Stahl. ''The Day the Laughter Stopped'' by David Yallop and ''Frame-Up! The Untold Story of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle'' by Andy Edmonds are other books on Arbuckle's life. The 1963 novel ''Scandal in Eden'' by Garet Rogers is a fictionalized version of the Arbuckle scandal.

Fatty Arbuckle's

Fatty Arbuckle's American Diners was an American-themed restaurant chain in the United Kingdom. The Manchester-based business was founded in 1983 by Pete Shotton, an associate of The Beatles. It focused on large portions at cheap prices. The name ...

was an American-themed restaurant chain in the UK named after Arbuckle.

The 2009 novel ''Devil's Garden'' is based on the Arbuckle trials. The main character in the story is Dashiell Hammett

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (; May 27, 1894 – January 10, 1961) was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the enduring characters he created are Sam Spade ('' ...

, a Pinkerton detective in San Francisco at the time of the trials.

NOFX

NOFX () is an American punk rock band formed in Los Angeles, California in 1983. Vocalist/bassist Fat Mike, guitarist Eric Melvin and drummer Erik Sandin are original founding and longest-serving members of the band, who have appeared on ever ...

's 2012 album '' Self Entitled'' has a song called ''I, Fatty'' about Arbuckle.

The 2020 remake of ''Perry Mason

Perry Mason is a fictional character, an American criminal defense lawyer who is the main character in works of detective fiction written by Erle Stanley Gardner. Perry Mason features in 82 novels and 4 short stories, all of which involve a c ...

'' features a minor character named Chubby Carmichael who is based on Arbuckle.

The 2021 French graphic novel ''Fatty : le premier roi d'Hollywood'', by Nadar and Julien Frey, portrays the period from Arbuckle's early days in Hollywood to his death.

Arbuckle is referred to in a nonsensical fashion in "Have You Seen Me?", a song by comedy metal band GWAR

Gwar, often stylized as GWAR, is an American heavy metal band formed in Richmond, Virginia in 1984, composed of and operated by a frequently rotating line-up of musicians, artists and filmmakers collectively known as Slave Pit Inc. After th ...

on their album ''America Must Be Destroyed

''America Must Be Destroyed'' is Gwar’s third album, released in 1992 as their second album on Metal Blade Records. The album’s lyrical content was inspired by controversy over obscenity charges against the band and an incident in Charlotte, ...

''.

Filmography

See also

*List of actors with Hollywood Walk of Fame motion picture stars