Rolls-Royce R on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Rolls-Royce R is a British

The Rolls-Royce Racing Engines

''Flight'', p. 990. www.flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 14 November 2009. To make the R as compact as possible, several design modifications were made in comparison to the Buzzard: the propeller reduction gear housing was reshaped, and the

To make the R as compact as possible, several design modifications were made in comparison to the Buzzard: the propeller reduction gear housing was reshaped, and the

The Rolls-Royce Racing Engines

''Flight'', p. 989. www.flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 14 November 2009. The engine's length was minimised by not staggering its cylinder banks fore and aft, which meant that the connecting rods from opposing cylinders had to share a short

The keys to the R engine's high

The keys to the R engine's high

According to Arthur Rubbra's memoirs, a de-rated version of the R engine, known by the name ''Griffon'' at that time, was tested in 1933. This engine, ''R11'', was used for "Moderately Supercharged Buzzard development" (which was not proceeded with until much later), and bore no direct relationship to the volume-produced Griffon of the 1940s.

The pre-production Griffon I shared the R engine's bore and

According to Arthur Rubbra's memoirs, a de-rated version of the R engine, known by the name ''Griffon'' at that time, was tested in 1933. This engine, ''R11'', was used for "Moderately Supercharged Buzzard development" (which was not proceeded with until much later), and bore no direct relationship to the volume-produced Griffon of the 1940s.

The pre-production Griffon I shared the R engine's bore and

During the 1929 race at

During the 1929 race at

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

;Supermarine S.6

Immediately after the 1929 Schneider Trophy contest

;Supermarine S.6

Immediately after the 1929 Schneider Trophy contest

''

;''Miss England II'' and ''III''

Two R engines, ''R17'' and ''R19'', were built for Sir Henry Segrave's twin-engined water speed record boat '' Miss England II'', this craft being ready for trials on

''

;''Miss England II'' and ''III''

Two R engines, ''R17'' and ''R19'', were built for Sir Henry Segrave's twin-engined water speed record boat '' Miss England II'', this craft being ready for trials on

''Note:''

;Air speed record

: Supermarine S.6: 8 September 1929 – 355.8 mph (572.6 km/h)

: Supermarine S.6B: 29 September 1931 – 407.5 mph (656 km/h)

;Land speed record

:'' Blue Bird'': 3 September 1935 – 301 mph (484 km/h)

:''

''Note:''

;Air speed record

: Supermarine S.6: 8 September 1929 – 355.8 mph (572.6 km/h)

: Supermarine S.6B: 29 September 1931 – 407.5 mph (656 km/h)

;Land speed record

:'' Blue Bird'': 3 September 1935 – 301 mph (484 km/h)

:''

Nineteen R engines were produced at Derby between 1929 and 1931, all given odd serial numbers. This was a Rolls-Royce convention when the propeller rotated anticlockwise when viewed from the front, but an exception was made for ''R17'', the sole clockwise-rotation R engine. There is some confusion as to whether 19 or 20 R engines were produced. In his notes Leo Villa refers to an ''R18'' engine, but according to Holter this may have been ''R17'' converted to clockwise rotation at the request of Malcolm Campbell rather than an additional example. There was no ''R13'' as Rolls-Royce never used the number 13 in any of their designations. A summary production list is given below:

;1929 Development engines

:''R1'', ''R3'' and ''R5''

;1929 Schneider Trophy engines

:''R7'', ''R9'' and ''R15''

;1930 Development engine

:''R11''

;1930 Wakefield order for ''Miss England II''

:''R17'' and ''R19''

;1931 Schneider Trophy engines

:''R21'', ''R23'', ''R25'', ''R27'', ''R29'' and ''R31''

;1931 Development/factory spare engines

:''R33'', ''R35'', ''R37'' and ''R39''

Nineteen R engines were produced at Derby between 1929 and 1931, all given odd serial numbers. This was a Rolls-Royce convention when the propeller rotated anticlockwise when viewed from the front, but an exception was made for ''R17'', the sole clockwise-rotation R engine. There is some confusion as to whether 19 or 20 R engines were produced. In his notes Leo Villa refers to an ''R18'' engine, but according to Holter this may have been ''R17'' converted to clockwise rotation at the request of Malcolm Campbell rather than an additional example. There was no ''R13'' as Rolls-Royce never used the number 13 in any of their designations. A summary production list is given below:

;1929 Development engines

:''R1'', ''R3'' and ''R5''

;1929 Schneider Trophy engines

:''R7'', ''R9'' and ''R15''

;1930 Development engine

:''R11''

;1930 Wakefield order for ''Miss England II''

:''R17'' and ''R19''

;1931 Schneider Trophy engines

:''R21'', ''R23'', ''R25'', ''R27'', ''R29'' and ''R31''

;1931 Development/factory spare engines

:''R33'', ''R35'', ''R37'' and ''R39''

;Aircraft

* Supermarine S.6

* Supermarine S.6A

* Supermarine S.6B

;Cars

*''

;Aircraft

* Supermarine S.6

* Supermarine S.6A

* Supermarine S.6B

;Cars

*''

;''R25''

The

;''R25''

The

1929 Schneider Trophy, original footage and soundtrack

''Note:'' Requires

Campbell-Railton Blue Bird, ''The Motor'', 10 January 1933 – Design detailsRolls-Royce.com, 2002 C.S. Rolls lecture – Details and image of the Rolls-Royce R (Pages 12–13)

{{featured article R 1920s aircraft piston engines

aero engine

An aircraft engine, often referred to as an aero engine, is the power component of an aircraft propulsion system. Most aircraft engines are either piston engines or gas turbines, although a few have been rocket powered and in recent years many ...

that was designed and built specifically for air racing

Air racing is a type of motorsport that involves airplanes or other types of aircraft that compete over a fixed course, with the winner either returning the shortest time, the one to complete it with the most points, or to come closest to a previ ...

purposes by Rolls-Royce Limited

Rolls-Royce was a British luxury car and later an aero-engine manufacturing business established in 1904 in Manchester by the partnership of Charles Rolls and Henry Royce. Building on Royce's good reputation established with his cranes, they ...

. Nineteen R engines were assembled in a limited production run between 1929 and 1931. Developed from the Rolls-Royce Buzzard

The Rolls-Royce Buzzard was a British piston aero engine of capacity that produced about . Designed and built by Rolls-Royce Limited it is a V12 engine of Bore and Stroke. Only 100 were made. A further development was the Rolls-Royce R e ...

, it was a 37-litre (2,240 cu in) capacity, supercharged

In an internal combustion engine, a supercharger compresses the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to produce more power for a given displacement.

The current categorisation is that a supercharger is a form of forced indu ...

V-12 capable of producing just under 2,800 horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are t ...

(2,090 kW), and weighed 1,640 pounds (770 kg). Intensive factory testing revealed mechanical failures which were remedied by redesigning the components, greatly improving reliability.

The R was used with great success in the Schneider Trophy seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

competitions held in England in 1929 and 1931. Shortly after the 1931 competition, an R engine using a special fuel blend powered the winning Supermarine S.6B aircraft to a new airspeed record

An air speed record is the highest airspeed attained by an aircraft of a particular class. The rules for all official aviation records are defined by Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), which also ratifies any claims. Speed records ...

of over 400 miles per hour (640 km/h). Continuing through the 1930s, both new and used R engines were used to achieve various land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isla ...

and water speed records by such racing personalities as Sir Henry Segrave, Sir Malcolm Campbell

Major Sir Malcolm Campbell (11 March 1885 – 31 December 1948) was a British racing motorist and motoring journalist. He gained the world speed record on land and on water at various times, using vehicles called ''Blue Bird'', including a ...

and his son Donald

Donald is a masculine given name derived from the Gaelic name ''Dòmhnall''.. This comes from the Proto-Celtic *''Dumno-ualos'' ("world-ruler" or "world-wielder"). The final -''d'' in ''Donald'' is partly derived from a misinterpretation of the ...

, the last record being set in 1939. A final R-powered water speed record attempt by Donald Campbell in 1951 was unsuccessful.

The experience gained by Rolls-Royce and Supermarine designers from the R engine was invaluable in the subsequent development of the Rolls-Royce Merlin

The Rolls-Royce Merlin is a British liquid-cooled V-12 piston aero engine of 27-litres (1,650 cu in) capacity. Rolls-Royce designed the engine and first ran it in 1933 as a private venture. Initially known as the PV-12, it was late ...

engine and the Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

. A de-rated R engine, known as the ''Griffon'', was tested in 1933, but it was not directly related to the production Rolls-Royce Griffon

The Rolls-Royce Griffon is a British 37- litre (2,240 cu in) capacity, 60-degree V-12, liquid-cooled aero engine designed and built by Rolls-Royce Limited. In keeping with company convention, the Griffon was named after a bird of pre ...

of 1939, of the same exact bore/stroke and resultant displacement figures as the "R" design. Three examples of the R engine are on public display in British museums as of 2014.

Design and development

Origin

Rolls-Royce realised that theNapier Lion

The Napier Lion is a 12-cylinder, petrol-fueled 'broad arrow' W12 configuration aircraft engine built by D. Napier & Son from 1917 until the 1930s. A number of advanced features made it the most powerful engine of its day and kept it in produ ...

engine used in the 1927 Supermarine S.5

The Supermarine S.5 was a 1920s British single-engined single-seat racing seaplane built by Supermarine. Designed specifically for the Schneider Trophy competition, the S.5 was the progenitor of a line of racing aircraft that ultimately led to ...

Schneider Trophy winner had reached the peak of its development, and that for Britain's entrant in the next race to be competitive a new, more powerful engine design was required. The first configuration drawing of the "Racing H" engine, based on the Buzzard

Buzzard is the common name of several species of birds of prey.

''Buteo'' species

* Archer's buzzard (''Buteo archeri'')

* Augur buzzard (''Buteo augur'')

* Broad-winged hawk (''Buteo platypterus'')

* Common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'')

* Eastern ...

, was sent to R. J. Mitchell of Supermarine

Supermarine was a British aircraft manufacturer that is most famous for producing the Spitfire fighter plane during World War II as well as a range of seaplanes and flying boats, and a series of jet-powered fighter aircraft after World War II ...

on 3 July 1928, allowing Mitchell to start design of the new S.6 Schneider Trophy seaplane. Shortly after this the engine's name was changed to R for "Racing".Holter 2002, p. 35. An official British Government contract to proceed with the project was not awarded until February 1929, leaving Rolls-Royce six months to develop the engine before the planned Schneider Trophy competition of that year.

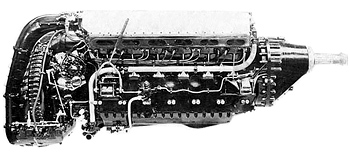

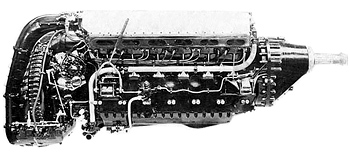

Description

The R was a physically imposing engine designed by a team led by Ernest Hives and includingCyril Lovesey

Alfred Cyril Lovesey CBE, AFRAeS, was an English engineer who was a key figure in the development of the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine.

Early life

Lovesey was born 15 July 1899 in Hereford the son of Alfred and Jessie Lovesey. 1901 Census ...

, Arthur Rowledge

Arthur John Rowledge, (30 July 1876 – 11 December 1957) was an English engineer who designed the Napier Lion aero engine and was a key figure in the development of the Rolls-Royce Merlin.

Career

Rowledge was born in Peterborough, Northampton ...

and Henry Royce

Sir Frederick Henry Royce, 1st Baronet, (27 March 1863 – 22 April 1933) was an English engineer famous for his designs of car and aeroplane engines with a reputation for reliability and longevity. With Charles Rolls (1877–1910) and Claude ...

. The R shared the Buzzard's bore, stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

and capacity, and used the same 60- degree V-12 layout. A new single-stage, double-sided supercharger

In an internal combustion engine, a supercharger compresses the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to produce more power for a given displacement.

The current categorisation is that a supercharger is a form of forced indu ...

impeller was designed along with revised cylinders

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an in ...

and strengthened connecting rod

A connecting rod, also called a 'con rod', is the part of a piston engine which connects the piston to the crankshaft. Together with the crank, the connecting rod converts the reciprocating motion of the piston into the rotation of the crank ...

s.Eves 2001, p. 225. The wet-liner cylinder block

In an internal combustion engine, the engine block is the structure which contains the cylinders and other components. In an early automotive engine, the engine block consisted of just the cylinder block, to which a separate crankcase was attac ...

s, crankcase

In a piston engine, the crankcase is the housing that surrounds the crankshaft. In most modern engines, the crankcase is integrated into the engine block.

Two-stroke engines typically use a crankcase-compression design, resulting in the fuel ...

and propeller reduction gear castings were produced from " R.R 50" aluminium alloy

An aluminium alloy (or aluminum alloy; see spelling differences) is an alloy in which aluminium (Al) is the predominant metal. The typical alloying elements are copper, magnesium, manganese, silicon, tin, nickel and zinc. There are two pr ...

; and because of the short life expectancy of these engines, forged aluminium was used to replace bronze and steel in many parts.taff author

Taff may refer to:

* River Taff, a large river in Wales

* ''Taff'' (TV series), a German tabloid news programme

* Trans-Atlantic Fan Fund, an organisation for science fiction fandom

People

* a demonym for anyone from south Wales

* Jerry Taff (b ...

2 October 1931.The Rolls-Royce Racing Engines

''Flight'', p. 990. www.flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 14 November 2009.

camshaft

A camshaft is a shaft that contains a row of pointed cams, in order to convert rotational motion to reciprocating motion. Camshafts are used in piston engines (to operate the intake and exhaust valves), mechanically controlled ignition systems ...

and rocker covers were modified to fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

into the shape of the aircraft's nose, the air intake was positioned in the vee of the engine (which also helped to avoid the ingress of spray), and beneath the engine the auxiliaries

Auxiliaries are support personnel that assist the military or police but are organised differently from regular forces. Auxiliary may be military volunteers undertaking support functions or performing certain duties such as garrison troops, ...

were raised a little to reduce the depth of the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

."taff author

Taff may refer to:

* River Taff, a large river in Wales

* ''Taff'' (TV series), a German tabloid news programme

* Trans-Atlantic Fan Fund, an organisation for science fiction fandom

People

* a demonym for anyone from south Wales

* Jerry Taff (b ...

2 October 1931.The Rolls-Royce Racing Engines

''Flight'', p. 989. www.flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 14 November 2009. The engine's length was minimised by not staggering its cylinder banks fore and aft, which meant that the connecting rods from opposing cylinders had to share a short

crankshaft

A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating shaft containing one or more crankpins, that are driven by the pistons via the connecti ...

bearing journal known as the "big end

Big or BIG may refer to:

* Big, of great size or degree

Film and television

* ''Big'' (film), a 1988 fantasy-comedy film starring Tom Hanks

* '' Big!'', a Discovery Channel television show

* ''Richard Hammond's Big'', a television show present ...

". This was initially achieved by fitting one connecting rod inside the other at the lower end in a blade and fork arrangement; however, after cracking of the connecting rods was found during testing in 1931, the rod design was changed to an articulated type.

The introduction of articulated connecting rods was regarded as a "nuisance" by Arthur Rubbra, a Rolls-Royce engine designer, as there were inherent problems with the arrangement. The complicated geometry meant that a pair of rods had different effective lengths, giving a longer stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

on the articulated side; consequently the cylinder liners on that side had to be lengthened to prevent the lower piston ring

A piston ring is a metallic split ring that is attached to the outer diameter of a piston in an internal combustion engine or steam engine.

The main functions of piston rings in engines are:

# Sealing the combustion chamber so that there is min ...

from running out of the cylinder skirt. Articulated rods were used in the Goshawk

Goshawk may refer to several species of birds of prey, mainly in the genus ''Accipiter'':

* Northern goshawk, ''Accipiter gentilis'', often referred to simply as the goshawk, since it is the only goshawk found in much of its range (in Europe and N ...

engine, but were not embodied in the later Rolls-Royce Merlin

The Rolls-Royce Merlin is a British liquid-cooled V-12 piston aero engine of 27-litres (1,650 cu in) capacity. Rolls-Royce designed the engine and first ran it in 1933 as a private venture. Initially known as the PV-12, it was late ...

, for which Arthur Rowledge had designed a revised blade and fork system.

Later production R engines featured sodium-filled exhaust valve

A poppet valve (also called mushroom valve) is a valve typically used to control the timing and quantity of gas or vapor flow into an engine.

It consists of a hole or open-ended chamber, usually round or oval in cross-section, and a plug, usual ...

stems for improved cooling, while additional modifications included a redesigned lower crankcase casting and the introduction of an oil scraper ring below the piston gudgeon pin

In internal combustion engines, the gudgeon pin (UK, wrist pin or piston pin US) connects the piston to the connecting rod, and provides a bearing for the connecting rod to pivot upon as the piston moves.Nunney, Malcolm James (2007) "The Reciproc ...

; a measure that was carried over to the Merlin engine. A balanced crankshaft was introduced in May 1931, and the compression ratio

The compression ratio is the ratio between the volume of the cylinder and combustion chamber in an internal combustion engine at their maximum and minimum values.

A fundamental specification for such engines, it is measured two ways: the stati ...

on the "sprint" engines prepared for that year was raised from 6:1 to 7:1.

The ignition system

An ignition system generates a spark or heats an electrode to a high temperature to ignite a fuel-air mixture in spark ignition internal combustion engines, oil-fired and gas-fired boilers, rocket engines, etc. The widest application for spark i ...

consisted of two rear-mounted, crankshaft-driven magneto

A magneto is an electrical generator that uses permanent magnets to produce periodic pulses of alternating current. Unlike a dynamo, a magneto does not contain a commutator to produce direct current. It is categorized as a form of alternator, ...

s, each supplying one of a pair of spark plugs

A spark plug (sometimes, in British English, a sparking plug, and, colloquially, a plug) is a device for delivering electric current from an ignition system to the combustion chamber of a spark-ignition engine to ignite the compressed fuel/air ...

fitted to each cylinder. This is common practise for aero engines, as it ensures continued operation in the case of a single magneto failure, and has the advantage of more efficient combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combus ...

over a single spark plug application.

Cooling

Cooling

Cooling is removal of heat, usually resulting in a lower temperature and/or phase change. Temperature lowering achieved by any other means may also be called cooling.ASHRAE Terminology, https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/free-resources/as ...

this large engine whilst minimising aerodynamic drag posed new challenges for both the Rolls-Royce and Supermarine design teams. Traditional cooling methods using honeycomb-type radiator

Radiators are heat exchangers used to transfer thermal energy from one medium to another for the purpose of cooling and heating. The majority of radiators are constructed to function in cars, buildings, and electronics.

A radiator is always ...

s were known to cause high drag in flight; consequently it was decided to use the surface skins of the S.6 wings and floats as heat exchangers, employing a double-skinned structure through which the coolant could circulate. Engine oil was cooled in a similar manner using channels in the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

and empennage

The empennage ( or ), also known as the tail or tail assembly, is a structure at the rear of an aircraft that provides stability during flight, in a way similar to the feathers on an arrow.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third e ...

skins. The S.6 was described at the time as a "flying radiator", and it had been estimated that this coolant system dissipated the equivalent of 1,000 hp (745 kW) of heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

in flight. However, even with this system in use, engine overheating was noted during the race flights, requiring the pilots to reduce the throttle setting to maintain a safe operating temperature

An operating temperature is the allowable temperature range of the local ambient environment at which an electrical or mechanical device operates. The device will operate effectively within a specified temperature range which varies based on the de ...

.

A not-so-obvious cooling measure was the deliberate use of a rich fuel mixture, which accounts for the frequent reports of black smoke seen issuing from the engine exhaust stubs. Although this robbed the engine of some power, it increased reliability and reduced the possibility of detonation

Detonation () is a type of combustion involving a supersonic exothermic front accelerating through a medium that eventually drives a shock front propagating directly in front of it. Detonations propagate supersonically through shock waves with s ...

in the cylinders.

Supercharger and fuel

power-to-weight ratio

Power-to-weight ratio (PWR, also called specific power, or power-to-mass ratio) is a calculation commonly applied to engines and mobile power sources to enable the comparison of one unit or design to another. Power-to-weight ratio is a measuremen ...

were its supercharger

In an internal combustion engine, a supercharger compresses the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to produce more power for a given displacement.

The current categorisation is that a supercharger is a form of forced indu ...

design, ability to run at high revolutions due to its structural strength, and the special blends of fuel used. The double-sided supercharger impeller was a new development for Rolls-Royce: running at a ratio of almost 8:1, it could supply intake air at up to 18 pounds per square inch

The pound per square inch or, more accurately, pound-force per square inch (symbol: lbf/in2; abbreviation: psi) is a unit of pressure or of stress based on avoirdupois units. It is the pressure resulting from a force of one pound-force applied t ...

(psi) (1.24 bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

) above atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, ...

, a figure known as "boost" and commonly abbreviated as "+'' x'' lb".Holter 2002, p. 175. By comparison the maximum boost of the earlier Rolls-Royce Kestrel

The Kestrel or type F is a 21 litre (1,300 in³) 700 horsepower (520 kW) class V-12 aircraft engine from Rolls-Royce, their first cast-block engine and the pattern for most of their future piston-engine designs. Used during the interwar ...

design was +6 lb (0.4 bar), this figure not being achieved until 1934. The high boost pressures initially caused the spark plugs

A spark plug (sometimes, in British English, a sparking plug, and, colloquially, a plug) is a device for delivering electric current from an ignition system to the combustion chamber of a spark-ignition engine to ignite the compressed fuel/air ...

to fail on test, and eventually the Lodge

Lodge is originally a term for a relatively small building, often associated with a larger one.

Lodge or The Lodge may refer to:

Buildings and structures Specific

* The Lodge (Australia), the official Canberra residence of the Prime Minist ...

type X170 plug was chosen as it proved to be extremely reliable.

The development of special fuel was attributed to the work of "Rod" Banks, an engineer who specialised in fuels and engine development. After using neat benzole

In the United Kingdom, benzole or benzol is a coal-tar product consisting mainly of benzene and toluene. It was originally used as a 'motor spirit', as was petroleum spirits. Benzole was also blended with petrol and sold as a motor fuel under tra ...

for early ground test runs, a mixture of 11% aviation petrol and 89% benzole plus 5 cubic centimetre

A cubic centimetre (or cubic centimeter in US English) (SI unit symbol: cm3; non-SI abbreviations: cc and ccm) is a commonly used unit of volume that corresponds to the volume of a cube that measures 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm. One cu ...

s (cc) of tetra-ethyl lead per Imperial gallon

The gallon is a unit of volume in imperial units and United States customary units. Three different versions are in current use:

*the imperial gallon (imp gal), defined as , which is or was used in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, Austral ...

(4.5 L) was tried. This blend of fuel was used to win the 1929 Schneider Trophy race, and continued to be used until June 1931.Eves 2001, p. 230. It was discovered that adding 10% methanol

Methanol (also called methyl alcohol and wood spirit, amongst other names) is an organic chemical and the simplest aliphatic alcohol, with the formula C H3 O H (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often abbreviated as MeOH). It is ...

to this mixture resulted in a 20 hp (15 kW) increase, with the further advantage of reduced fuel weight – particularly important for aircraft use – due to its lowered specific gravity

Relative density, or specific gravity, is the ratio of the density (mass of a unit volume) of a substance to the density of a given reference material. Specific gravity for liquids is nearly always measured with respect to water at its dens ...

. For the 1931 airspeed record attempt acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscibl ...

was added to prevent intermittent misfiring; the composition of this final blend was 30% benzole, 60% methanol, and 10% acetone, plus 4.2 cc of tetra-ethyl lead per gallon.

On an early test run the R engine produced 1,400 hp (1,040 kW) and was noted to idle happily at 450 revolutions per minute

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensio ...

(rpm). With increased boost ratings and fuel developed by Banks, the R engine ultimately developed 2,530 hp (1,890 kW) at 3,200 rpm; well over double the maximum power output of the Buzzard

Buzzard is the common name of several species of birds of prey.

''Buteo'' species

* Archer's buzzard (''Buteo archeri'')

* Augur buzzard (''Buteo augur'')

* Broad-winged hawk (''Buteo platypterus'')

* Common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'')

* Eastern ...

. The engine was further tested and cleared for limited sprint racing at 2,783 hp (2,075 kW) at 3,400 rpm and +21 lb (1.45 bar) of boost, but this capability was not used due to concerns with the S.6B's airframe

The mechanical structure of an aircraft is known as the airframe. This structure is typically considered to include the fuselage, undercarriage, empennage and wings, and excludes the propulsion system.

Airframe design is a field of aerospa ...

not being able to withstand the power, and the inability of the aircraft to lift the extra fuel required to meet the increased consumption.Lumsden 2003, p. 199.

Testing

Ground testing

The first run of engine ''R1'' took place at Rolls-Royce'sDerby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

factory on 7 April 1929 with ''R7'' running the next day. Many mechanical failures were experienced during bench testing including burnt valves, connecting rod breakages and main bearing

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

seizures,Holter 2002, p. 38. while considerably more trouble than expected occurred with valve springs; at one time two or three would be found broken after a 10-minute run, but the continual redesigning and testing of components reduced all these problems. Unknown to Royce himself, the engineers had also fitted " Wellworthy" pistons that were better able to withstand the 13 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s "pressure" of each firing stroke.Holter 2002, p. 38.

Ground testing of the R involved the use of three Kestrel

The term kestrel (from french: crécerelle, derivative from , i.e. ratchet) is the common name given to several species of predatory birds from the falcon genus ''Falco''. Kestrels are most easily distinguished by their typical hunting behaviou ...

engines: one to simulate a headwind or airspeed

In aviation, airspeed is the speed of an aircraft relative to the air. Among the common conventions for qualifying airspeed are:

* Indicated airspeed ("IAS"), what is read on an airspeed gauge connected to a Pitot-static system;

* Calibrated ...

, one to provide ventilation of the test area, and another to cool the crankcase

In a piston engine, the crankcase is the housing that surrounds the crankshaft. In most modern engines, the crankcase is integrated into the engine block.

Two-stroke engines typically use a crankcase-compression design, resulting in the fuel ...

. Superchargers could be tested on a separate rig that was driven by another Kestrel engine. Eight men were required to run a test cell, led by the "Chief Tester" who had the tasks of logging the figures and directing the other operators. One of these chief testers was Victor Halliwell who later lost his life whilst on board the water speed record contender '' Miss England II''. The conditions in the test cell were particularly unpleasant; deafness and tinnitus

Tinnitus is the perception of sound when no corresponding external sound is present. Nearly everyone experiences a faint "normal tinnitus" in a completely quiet room; but it is of concern only if it is bothersome, interferes with normal hearin ...

lasting up to two days were experienced by test personnel even after plugging their ears with cotton wool

Cotton wool consists of silky fibers taken from cotton plants in their raw state. Impurities, such as seeds, are removed and the cotton is then bleached using hydrogen peroxide or sodium hypochlorite and sterilized. It is also a refined product ...

. Development time was short and the deafening sound of three Kestrels and an R engine running at high power for 24 hours a day took its toll on the local population. The Mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

of Derby stepped in and asked that the people endure the noise for the sake of British prestige; subsequently testing continued for seven months.

In the course of a 25-minute test an early R engine would consume 60 Imperial gallons (gal) (270 L) of pre-heated castor oil

Castor oil is a vegetable oil pressed from castor beans.

It is a colourless or pale yellow liquid with a distinct taste and odor. Its boiling point is and its density is 0.961 g/cm3. It includes a mixture of triglycerides in which about ...

. The majority of this was spat out of the exhaust ports and smothered the test cell walls, milk being given to staff to minimise the effects of this well-known laxative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

. Up to 200 gal (900 L) of the special fuel blend had to be mixed for each test, 80 gal (360 L) of which were used just to warm the engine to operating temperature. The same coarse-pitch propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

used for flight trials was fitted throughout these tests.

Flight testing

Overseen byCyril Lovesey

Alfred Cyril Lovesey CBE, AFRAeS, was an English engineer who was a key figure in the development of the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine.

Early life

Lovesey was born 15 July 1899 in Hereford the son of Alfred and Jessie Lovesey. 1901 Census ...

, flight testing commenced on 4 August 1929 in the new Supermarine S.6 at RAF Calshot, a seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

and flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

station on Southampton Water in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

.Eves 2001, p. 177. During pre-race scrutineering tests, metal particles were found on two of the engine's 24 spark plugs

A spark plug (sometimes, in British English, a sparking plug, and, colloquially, a plug) is a device for delivering electric current from an ignition system to the combustion chamber of a spark-ignition engine to ignite the compressed fuel/air ...

indicating a piston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder and is made gas-t ...

failure which would require an engine re-build or replacement. The competition rules did not allow an engine change, but due to the foresight of Ernest Hives, several Rolls-Royce engineers and mechanics that were familiar with the R had travelled down to Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

to witness the trials, and with their assistance one cylinder bank was removed, the damaged piston replaced and the cylinder refurbished. This work was completed overnight and allowed the team to continue in the competition.

Engine starting was achieved by a combination of compressed air and a hand-turned magneto

A magneto is an electrical generator that uses permanent magnets to produce periodic pulses of alternating current. Unlike a dynamo, a magneto does not contain a commutator to produce direct current. It is categorized as a form of alternator, ...

; however, starting problems were encountered during pre-race testing at Calshot due to moisture in the air and water contamination of the fuel. A complicated test procedure was devised to ensure clean fuel for competition flights since more than 0.3% water content made it unusable. As expected, minor engine failures continued to be experienced, and to counter this engines and parts were transported at high speed between Derby and Calshot using an adapted Rolls-Royce Phantom I

The Rolls-Royce Phantom was Rolls-Royce's replacement for the original Silver Ghost. Introduced as the New Phantom in 1925, the Phantom had a larger engine than the Silver Ghost and used pushrod-operated overhead valves instead of the Silver G ...

motor car. Travelling mostly after dark, this vehicle became known as the ''Phantom of The Night.''Holter 2002, p. 41.

Relationship to the Griffon and Merlin

stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

, but was otherwise a completely new design that first ran in the Experimental Department in November 1939. Although this single engine was never flown, the production version, the Griffon II, first flew in 1941 installed in the Fairey Firefly

The Fairey Firefly is a Second World War-era carrier-borne fighter aircraft and anti-submarine aircraft that was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm (FAA). It was developed and built by the British aircraft manufacturer Fairey Avia ...

. A significant difference between the R and the production Griffon was the re-location of the camshaft

A camshaft is a shaft that contains a row of pointed cams, in order to convert rotational motion to reciprocating motion. Camshafts are used in piston engines (to operate the intake and exhaust valves), mechanically controlled ignition systems ...

and supercharger drives to the front of the engine to reduce overall length. Another length-reducing measure was the use of a single magneto (the R had two, mounted at the rear), this again was moved to the front of the engine.

Further possible development work on the R engine was discussed in The National Archives

National archives are central archives maintained by countries. This article contains a list of national archives.

Among its more important tasks are to ensure the accessibility and preservation of the information produced by governments, both ...

' file AVIA 13/122, which contains a proposal from the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), before finally losing its identity in me ...

dated October and November 1932, to test four engines to destruction. This document states that there were five engines available for test purposes, the fifth to be used for a standard Type Test at high revolutions.

Although not directly related to the Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

, the Supermarine

Supermarine was a British aircraft manufacturer that is most famous for producing the Spitfire fighter plane during World War II as well as a range of seaplanes and flying boats, and a series of jet-powered fighter aircraft after World War II ...

engineers gained valuable experience of high-speed flight with the S.5 and S.6 aircraft, their next project being the Rolls-Royce Goshawk

The Rolls-Royce Goshawk was a development of the Rolls-Royce Kestrel that used evaporative or steam cooling. In line with Rolls-Royce convention of naming piston engines after birds of prey, it was named after the goshawk.

The engine first ...

-powered Supermarine Type 224 prototype fighter aircraft. Technological advances used in the R engine, such as sodium-cooled valves and spark plugs able to operate under high boost pressures, were incorporated into the Rolls-Royce Merlin

The Rolls-Royce Merlin is a British liquid-cooled V-12 piston aero engine of 27-litres (1,650 cu in) capacity. Rolls-Royce designed the engine and first ran it in 1933 as a private venture. Initially known as the PV-12, it was late ...

design. The author Steve Holter sums up the design of the Rolls-Royce R with these words:

Schneider Trophy use

The Schneider Trophy was a prestigious annual prize competition forseaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

s that was first held in 1913. The 1926 race was the first where all the teams fielded pilots from their armed forces, the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

financing a British team known as the High Speed Flight drawn from the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

. Sometimes known simply as The Flight, the team was formed at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment

The Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (MAEE) was a British military research and test organisation. It was originally formed as the Marine Aircraft Experimental Station in October 1918 at RAF Isle of Grain, a former Royal Naval Air Serv ...

, Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northeast of London.

H ...

, in preparation for the 1927 race in which Supermarine's Mitchell-designed, Napier Lion

The Napier Lion is a 12-cylinder, petrol-fueled 'broad arrow' W12 configuration aircraft engine built by D. Napier & Son from 1917 until the 1930s. A number of advanced features made it the most powerful engine of its day and kept it in produ ...

-powered Supermarine S.5

The Supermarine S.5 was a 1920s British single-engined single-seat racing seaplane built by Supermarine. Designed specifically for the Schneider Trophy competition, the S.5 was the progenitor of a line of racing aircraft that ultimately led to ...

s placed first and second. 1927 was the last annual competition, the event then moving onto a biannual schedule to allow more development time between races.

During the 1929 race at

During the 1929 race at Cowes

Cowes () is an English seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina, facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east bank. The two towns are linked by the Cowes Fl ...

between Great Britain and Italy, Richard Waghorn flying the Supermarine S.6 with the new Rolls-Royce R engine retained the Schneider Trophy for Great Britain with an average speed of , and also gained the 50 km and 100 km (31 mi and 62 mi) world speed records. The records were subsequently beaten when Richard Atcherley

Air Marshal Sir Richard Llewellyn Roger Atcherley, (12 January 1904 – 18 April 1970) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Pakistan Air Force from 1949 to 1951.

Early life

Richard Atcherley and ...

later registered higher speeds when he completed his laps of the circuit.Price 1986, p. 11. The Italian team placed second and fourth using Fiat AS.3

The Fiat AS.3 was an Italian 12-cylinder, liquid-cooled V engine designed and built in the mid-1920s by Fiat Aviazione especially for the 1927 Schneider Trophy air race.

Design and development

The AS.3 was an increased Bore (engine), bore and St ...

V-12-powered Macchi M.52

The Macchi M.52 was an Italian racing seaplane designed and built by Macchi for the 1927 Schneider Trophy race. The M.52 and a later variant, the M.52bis or M.52R, both set world speed records for seaplanes.

Design and development

M.52

Mario C ...

aircraft. Another racing seaplane, the Fiat C.29 powered by the AS.5 engine attended the contest but did not compete.

More comparable to the R engine was the Fiat AS.6

The Fiat AS.6 was an unusual Italian 24-cylinder, liquid-cooled V configured aircraft racing engine designed and built in the late-1920s by Fiat especially for the Schneider Trophy air races, but development and running problems meant that it ...

engine developed for the 1931 contest; effectively a coupled, double AS.5 that suffered from technical problems. With the assistance of Rod Banks, the AS.6 powered the Macchi M.C.72

The Macchi M.C. 72 is an experimental seaplane designed and built by the Italian aircraft company Macchi Aeronautica. The M.C. 72 held the world speed record for all aircraft for five years. In 1933 and 1934 it set world speed records for pisto ...

to a new speed record for piston-powered seaplanes in 1934 of 440.6 mph (709.2 km/h), a record that still stands as of 2009.

In 1931 the British Government withdrew financial support, but a private donation of £100,000 from Lucy, Lady Houston allowed Supermarine to compete on 13 September using the R-powered Supermarine S.6B. For this race the engine's rating was increased by to . The Italian and French entrants however, failed to ready their aircraft and crews in time for the competition, and the remaining British team set both a new world speed record at 379 mph (610 km/h) and, unopposed, won the trophy outright with a third consecutive victory. "The Flight" was wound up within weeks of the 1931 win as there were to be no more Schneider Trophy contests. The original Trophy is on display in the London Science Museum along with the S.6B that secured it, as well as the R engine that powered this aircraft for the subsequent airspeed record flight.Supermarine Seaplane S.6B, ''S1595'', Inventory number: 1932-532 (exhibit)www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

World speed record use

New airspeed records were set after the 1929 and 1931 Schneider Trophy contests, both achieved using the R engine. In the two decades before World War II, the quest to break the land speed record was hotly contested, particularly so in the early 1930s. Aero engines were often used to power wheeled vehicles to ever-higher speeds, chosen because of their highpower-to-weight ratio

Power-to-weight ratio (PWR, also called specific power, or power-to-mass ratio) is a calculation commonly applied to engines and mobile power sources to enable the comparison of one unit or design to another. Power-to-weight ratio is a measuremen ...

s: the Liberty engine

The Liberty L-12 is an American water-cooled 45° V-12 aircraft engine displacing and making designed for a high power-to-weight ratio and ease of mass production. It saw wide use in aero applications, and, once marinized, in marine use both ...

, Napier Lion

The Napier Lion is a 12-cylinder, petrol-fueled 'broad arrow' W12 configuration aircraft engine built by D. Napier & Son from 1917 until the 1930s. A number of advanced features made it the most powerful engine of its day and kept it in produ ...

and the Sunbeam Matabele

The Sunbeam Matabele was a British 12-cylinder aero engine that was first flown in 1918. The Matabele was the last iteration of one of Sunbeam's most successful aero engines, the Cossack.

Design and development

The Cossack was a twin overhead ...

were among the engine types used in the 1920s. The Rolls-Royce R was the latest development in high-powered aero engine design at the time, and was chosen by several makers of land speed record-contending cars; the engine was also chosen for powerboats attempting the water speed record. One car and two boats successfully used the combined power of two R engines.

Airspeed record

;Supermarine S.6

Immediately after the 1929 Schneider Trophy contest

;Supermarine S.6

Immediately after the 1929 Schneider Trophy contest Squadron Leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr in the RAF ; SQNLDR in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly sometimes S/L in all services) is a commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence. It is als ...

Augustus Orlebar

Air Vice Marshal Augustus Henry Orlebar, (17 February 1897 – 4 August 1943) was a British Army and Royal Air Force officer who served in both world wars.

After being wounded during the Gallipoli campaign, Orlebar was seconded to the Royal F ...

, commanding officer of the High Speed Flight, set a new airspeed record

An air speed record is the highest airspeed attained by an aircraft of a particular class. The rules for all official aviation records are defined by Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), which also ratifies any claims. Speed records ...

of 355.8 mph (572.6 km/h) using Supermarine S.6, ''N247.''Eves 2001, p. 193.

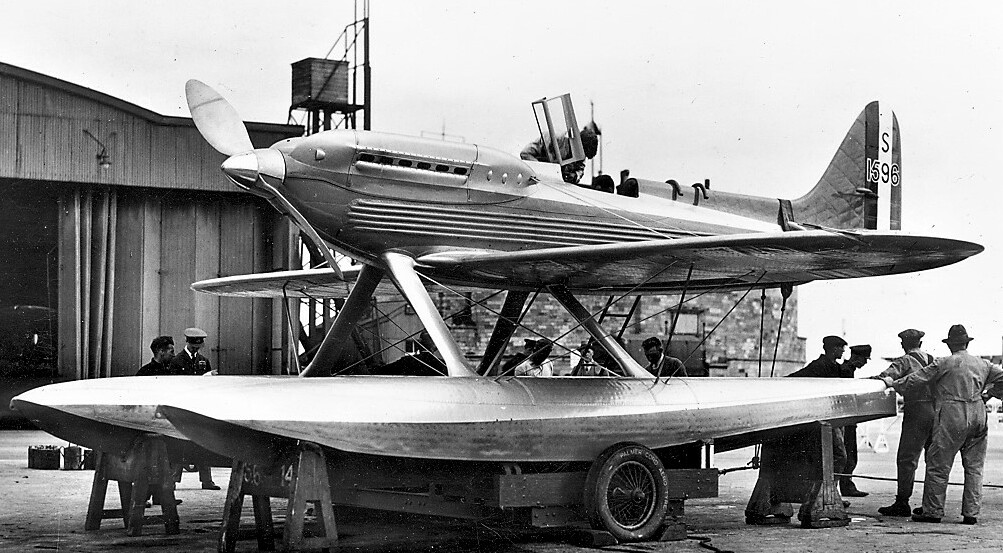

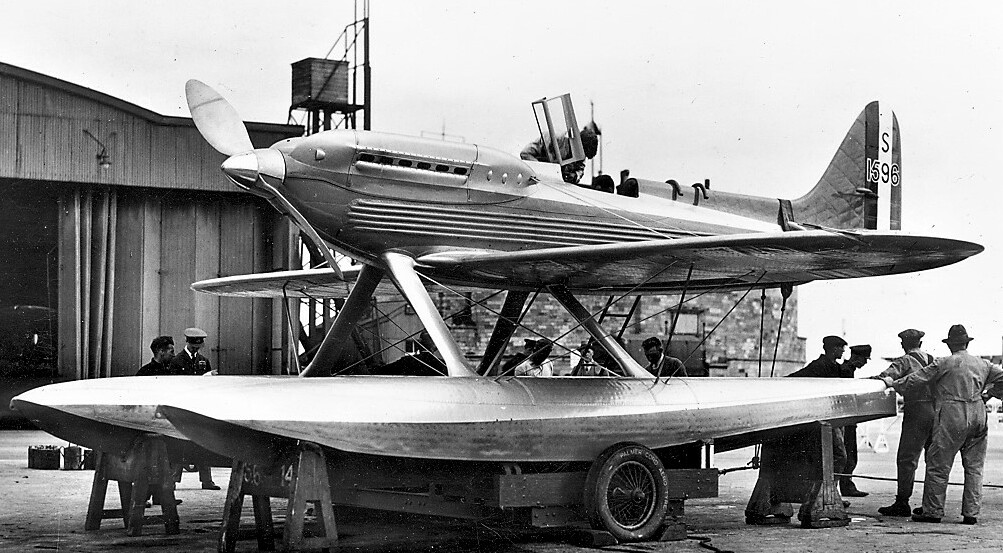

;Supermarine S.6B

On 29 September 1931, barely two weeks after the British team had secured the Schneider Trophy outright, Flight Lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior Officer (armed forces)#Commissioned officers, commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) RAF officer ranks, system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. I ...

George Stainforth

Wing Commander George Hedley Stainforth, (22 March 1899 – 27 September 1942) was a Royal Air Force pilot and the first man to exceed 400 miles per hour.

Early life

George Hedley Stainforth was the son of George Staunton Stainforth, a solicit ...

broke the world airspeed record in a Rolls-Royce R-powered Supermarine S.6B, serial ''S1595'', reaching an average speed of 407.5 mph (655.67 km/h). It had been intended to also use the identical sister aircraft, ''S1596'', for the attempt but Stainforth had capsized it on 16 September whilst testing a propeller.Eves 2001, p. 210.Price 1986, p. 10.

Land speed record

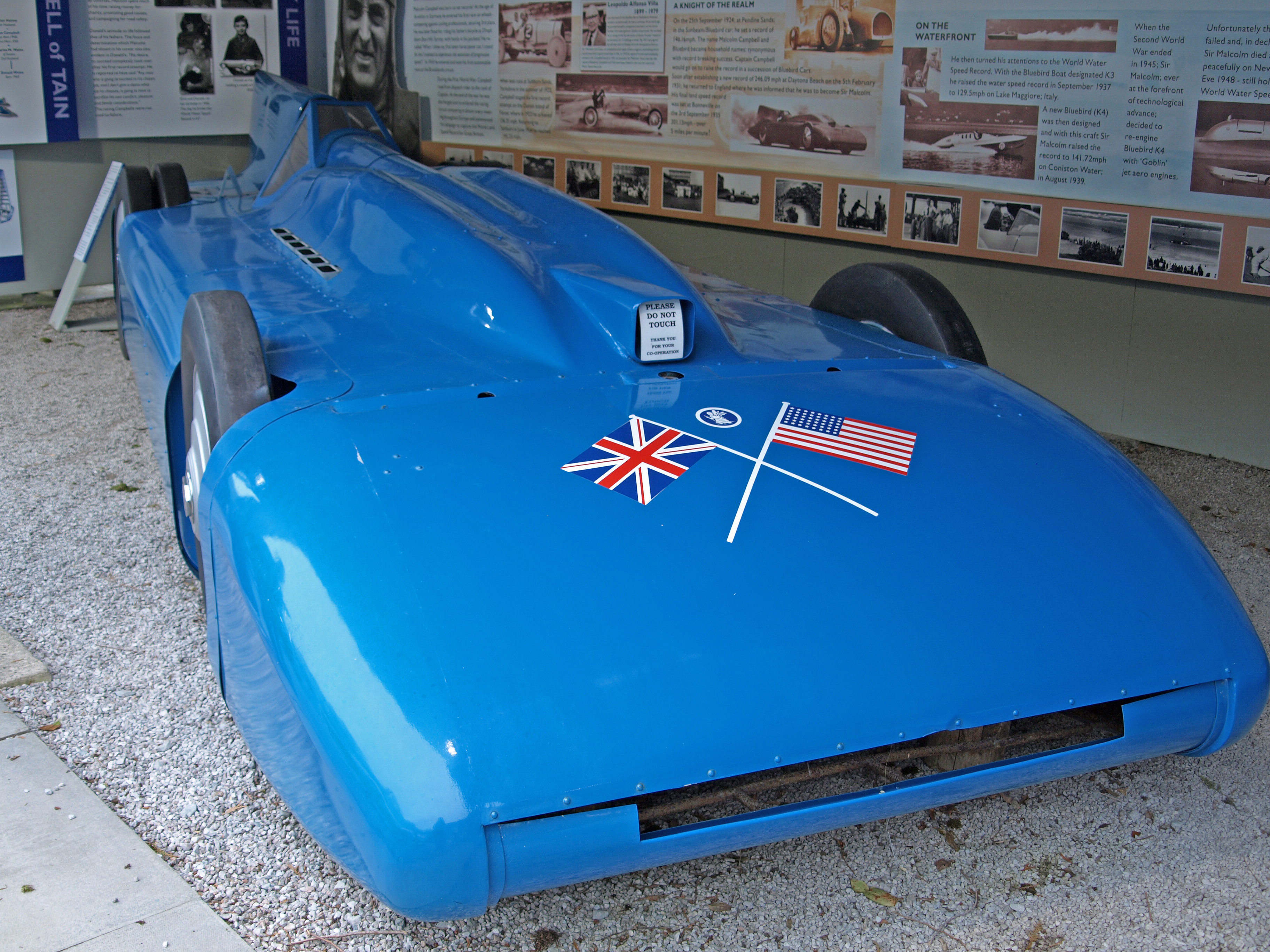

;''Campbell-Railton Blue Bird''Sir Malcolm Campbell

Major Sir Malcolm Campbell (11 March 1885 – 31 December 1948) was a British racing motorist and motoring journalist. He gained the world speed record on land and on water at various times, using vehicles called ''Blue Bird'', including a ...

, and later his son Donald

Donald is a masculine given name derived from the Gaelic name ''Dòmhnall''.. This comes from the Proto-Celtic *''Dumno-ualos'' ("world-ruler" or "world-wielder"). The final -''d'' in ''Donald'' is partly derived from a misinterpretation of the ...

, used R engines from 1931 to 1951. At Sir Malcolm's knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

ceremony in February 1931, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

expressed great interest in the R and asked many questions about its fuel consumption and performance.

In 1932, Campbell stated that he "... was fortunate in procuring a special R.R. Schneider Trophy engine" for his land speed record car to replace its Napier Lion

The Napier Lion is a 12-cylinder, petrol-fueled 'broad arrow' W12 configuration aircraft engine built by D. Napier & Son from 1917 until the 1930s. A number of advanced features made it the most powerful engine of its day and kept it in produ ...

. Lent to him by Rolls-Royce, this engine was either ''R25'' or ''R31''. By February 1933 the car, named '' Blue Bird'' had been rebuilt to accommodate the larger engine and was running at Daytona.

In late 1933 Campbell bought engine ''R37'' from Rolls-Royce; and had also been lent ''R17'' and ''R19'' by Lord Wakefield, and ''R39'' by Rolls-Royce. He then lent ''R17'' to George Eyston

Captain George Edward Thomas Eyston MC OBE (28 June 1897 – 11 June 1979) was a British engineer, inventor, and racing driver best known for breaking the land speed record three times between 1937 and 1939.

Early life

George Eyston was educ ...

. Once he had achieved the record on 3 September 1935 at the Bonneville Speedway

Bonneville Speedway (also known as the Bonneville Salt Flats Race Track) is an area of the Bonneville Salt Flats northeast of Wendover, Utah, that is marked out for motor sports. It is particularly noted as the venue for numerous land speed rec ...

, Campbell retired from further land speed endeavours.

Lord Wakefield arranged for a replica of the Rolls-Royce R to be exhibited at the 1933 Motor Show

An auto show, also known as a motor show or car show, is a public exhibition of current automobile models, debuts, concept cars, or out-of-production classics. It is attended by automotive industry representatives, dealers, auto journalists a ...

, held at Olympia, London

Olympia London, sometimes referred to as the Olympia Exhibition Centre, is an exhibition centre, event space and conference centre in West Kensington, in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, London, England. A range of internati ...

. A press report from the event provides an insight into the public perception of the engine:

''Blue Bird'' is now on display at the Daytona International Speedway

Daytona International Speedway is a race track in Daytona Beach, Florida, United States. Since opening in 1959, it has been the home of the Daytona 500, the most prestigious race in NASCAR as well as its season opening event. In addition to NASC ...

.

;''Thunderbolt''

During the mid-1930s, George Eyston set many speed records with his ''Speed of the Wind

Speed of the Wind was a record-breaking car of the 1930s, built for and driven by Captain George Eyston.

The car was designed by Eyston and E A D Eldridge, then built by the father of Tom Delaney It was powered by an unsupercharged version of t ...

'' car, powered by an unsupercharged Rolls-Royce Kestrel

The Kestrel or type F is a 21 litre (1,300 in³) 700 horsepower (520 kW) class V-12 aircraft engine from Rolls-Royce, their first cast-block engine and the pattern for most of their future piston-engine designs. Used during the interwar ...

. In 1937 he built a massive new car, ''Thunderbolt

A thunderbolt or lightning bolt is a symbolic representation of lightning when accompanied by a loud thunderclap. In Indo-European mythology, the thunderbolt was identified with the 'Sky Father'; this association is also found in later Hel ...

'', powered by two R engines to attempt the absolute land speed record. At first Eyston experienced clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device that engages and disengages power transmission, especially from a drive shaft to a driven shaft. In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts). ...

failure due to the combined power of the engines. Nevertheless, he took the record in November 1937, reaching 312 mph (502 km/h), and in 1938 when ''Thunderbolt'' reached 357.5 mph (575 km/h).Jennings 2004, p. 291. When first built at Bean Industries in Tipton

Tipton is an industrial town in the West Midlands in England with a population of around 38,777 at the 2011 UK Census. It is located northwest of Birmingham.

Tipton was once one of the most heavily industrialised towns in the Black Country, w ...

, the nearside engine fitted to ''Thunderbolt'' was ''R27'' which had powered ''S1595'' when it set the air speed record in 1931. The other was ''R25'', used by the same aircraft to win the Schneider Trophy two weeks earlier. Eyston had also borrowed ''R17'' from Sir Malcolm Campbell and, with the continuing support that Rolls-Royce extended to both Campbell and Eyston, he also had the option of using ''R39''.

Water speed record

''

;''Miss England II'' and ''III''

Two R engines, ''R17'' and ''R19'', were built for Sir Henry Segrave's twin-engined water speed record boat '' Miss England II'', this craft being ready for trials on

''

;''Miss England II'' and ''III''

Two R engines, ''R17'' and ''R19'', were built for Sir Henry Segrave's twin-engined water speed record boat '' Miss England II'', this craft being ready for trials on Windermere

Windermere (sometimes tautologically called Windermere Lake to distinguish it from the nearby town of Windermere) is the largest natural lake in England. More than 11 miles (18 km) in length, and almost 1 mile (1.5 km) at its wides ...

by June 1930. On Friday 13 June, Segrave was fatally injured and a Rolls-Royce technical advisor, Victor Halliwell, was killed when ''Miss England II'' capsized at high speed after possibly hitting a log. Shortly before his death Segrave learnt that he had set a new water speed record of just under 100 mph (160 km/h). On 18 July 1932, Kaye Don

Kaye Ernest Donsky (10 April 1891 – 29 August 1981), better known by his ''nom de course'' Kaye Don, was an Irish world record breaking car and speedboat racer. He became a motorcycle dealer on his retirement from road racing and set up Amba ...

set a new world water speed record of on Loch Lomond

Loch Lomond (; gd, Loch Laomainn - 'Lake of the Elms'Richens, R. J. (1984) ''Elm'', Cambridge University Press.) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault, often considered the boundary between the lowlands of ...

in a new boat, ''Miss England III

''Miss England III'' was the last of a series of speedboats used by Henry Segrave and Kaye Don to contest world water speed records in the 1920s and 1930s. She was the first craft in the Lloyds Unlimited Group of high-performance speedboats cre ...

'', which also used engines ''R17'' and ''R19''.

;''Blue Bird K3''

In late 1935, Sir Malcolm Campbell decided to challenge the water speed record. At that point he had two Napier Lion

The Napier Lion is a 12-cylinder, petrol-fueled 'broad arrow' W12 configuration aircraft engine built by D. Napier & Son from 1917 until the 1930s. A number of advanced features made it the most powerful engine of its day and kept it in produ ...

s and one Rolls-Royce R engine, ''R37'' at his disposal, and it was decided to install the R engine in ''Blue Bird K3

''Blue Bird K3'' is a hydroplane powerboat commissioned in 1937 by Sir Malcolm Campbell, to rival the Americans' efforts in the fight for the world water speed record. She set three world water speed records, first on Lake Maggiore in Septem ...

''. During trials on Loch Lomond

Loch Lomond (; gd, Loch Laomainn - 'Lake of the Elms'Richens, R. J. (1984) ''Elm'', Cambridge University Press.) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault, often considered the boundary between the lowlands of ...

in June 1937 the engine was "slightly damaged ... because of trouble with the circulating water system". In August 1937 ''Blue Bird K3'' was taken to Lake Maggiore

Lake Maggiore (, ; it, Lago Maggiore ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh Maggior; pms, Lagh Magior; literally 'Greater Lake') or Verbano (; la, Lacus Verbanus) is a large lake located on the south side of the Alps. It is the second largest l ...

in Italy where "the modified irculationsystem worked perfectly with a second engine", ''R39''.

;''Blue Bird K4 and the work of Leo Villa''

''R39'' was again used in 1939 in ''Blue Bird K4

''Blue Bird K4'' was a powerboat commissioned in 1939 by Sir Malcolm Campbell, to rival the Americans' efforts in the fight for the world water speed record.

The name "K4" was derived from its Lloyd's unlimited rating, and was carried in a prom ...

''. In 1947 Campbell unsuccessfully converted ''K4'' to jet power using a de Havilland Goblin

The de Havilland Goblin, originally designated as the Halford H-1, is an early turbojet engine designed by Frank Halford and built by de Havilland. The Goblin was the second British jet engine to fly, after Whittle's Power Jets W.1, and the ...

engine. After Campbell's death from natural causes in 1948, Donald Campbell bought ''K4'' for a nominal sum as well as the 1935 record car when his father's effects were auctioned. He also purchased ''R37'' back from a car dealer and reinstalled it in ''K4''. Attempts on the record were made in 1949, and again in 1951 when ''R37'' was "damaged beyond any immediate repair" by overheating. Another attempt was made later in the year using ''R39'', but ''K4'' suffered a structural failure and sank in Coniston Water

Coniston Water in the English county of Cumbria is the third-largest lake in the Lake District by volume (after Windermere and Ullswater), and the fifth-largest by area. It is five miles long by half a mile wide (8 km by 800 m), has a ...

. It was recovered and broken up on the shore.Holter 2002, p. 87.

The care and maintenance of the Campbell's R engines was entrusted to Leo Villa, a Cockney

Cockney is an accent and dialect of English, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by working-class and lower middle-class Londoners. The term "Cockney" has traditionally been used to describe a person from the East End, or ...

born to a Swiss father, who was described as "the man behind the Campbells" and a central figure who "fitted the first nut to the first bolt". Villa learnt his trade of "aircraft mechanic" in the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

; his first job was fitting Beardmore 160 hp

The Beardmore 160 hp is a British six-cylinder, water-cooled aero engine that first ran in 1916, it was built by Arrol-Johnston and Crossley Motors for William Beardmore and Company as a development of the Beardmore 120 hp, itself a licens ...

engines to airframes. After World War I he worked for a motor racing company and participated as co-driver and mechanic in several races.

Villa was first employed by Malcolm Campbell in 1922, and continued in the service of Donald Campbell until 1967, when Campbell was killed during a record attempt on Coniston Water. He was the chief caretaker of their R engines until the last R-powered record attempt in 1951, after which his responsibilities centred on Campbell's jet engines. Villa's many responsibilities included installing and removing the engines, repairing and tuning them, and operating the compressed air and magneto for starting them. During the World War II years, he was responsible for the upkeep of ''Blue Bird K4'' and the spare R engines, but unknown to him they had been sold along with ''K3''. Villa eventually took the three R engines to Thomson & Taylor at Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields ...

for long-term storage.

His relationship with Malcolm Campbell was strained at times: Campbell, with no engineering background, would often question Villa's intimate knowledge of the R engine, but his relations with Donald Campbell were much better, as they were of a similar age. At Lake Garda

Lake Garda ( it, Lago di Garda or ; lmo, label= Eastern Lombard, Lach de Garda; vec, Ƚago de Garda; la, Benacus; grc, Βήνακος) is the largest lake in Italy.

It is a popular holiday location in northern Italy, about halfway between ...

in 1951 Villa noted the willingness of "Don" to help with engineering tasks, and the difficulties of working on the R engine:

World speed record summary

''Note:''

;Air speed record

: Supermarine S.6: 8 September 1929 – 355.8 mph (572.6 km/h)

: Supermarine S.6B: 29 September 1931 – 407.5 mph (656 km/h)

;Land speed record

:'' Blue Bird'': 3 September 1935 – 301 mph (484 km/h)

:''

''Note:''

;Air speed record

: Supermarine S.6: 8 September 1929 – 355.8 mph (572.6 km/h)

: Supermarine S.6B: 29 September 1931 – 407.5 mph (656 km/h)

;Land speed record

:'' Blue Bird'': 3 September 1935 – 301 mph (484 km/h)

:''Thunderbolt

A thunderbolt or lightning bolt is a symbolic representation of lightning when accompanied by a loud thunderclap. In Indo-European mythology, the thunderbolt was identified with the 'Sky Father'; this association is also found in later Hel ...

'': 16 September 1938 – 357.5 mph (575 km/h)

;Water speed record

:'' Miss England II'': 9 July 1931 – 110.28 mph (177.48 km/h)

:''Miss England III

''Miss England III'' was the last of a series of speedboats used by Henry Segrave and Kaye Don to contest world water speed records in the 1920s and 1930s. She was the first craft in the Lloyds Unlimited Group of high-performance speedboats cre ...

'': 18 July 1932 – 119.81 mph (192.82 km/h)

:''Blue Bird K3

''Blue Bird K3'' is a hydroplane powerboat commissioned in 1937 by Sir Malcolm Campbell, to rival the Americans' efforts in the fight for the world water speed record. She set three world water speed records, first on Lake Maggiore in Septem ...

'': 17 August 1938 – 130.91 mph (210.67 km/h)Holter 2002, p. 171.

:''Blue Bird K4

''Blue Bird K4'' was a powerboat commissioned in 1939 by Sir Malcolm Campbell, to rival the Americans' efforts in the fight for the world water speed record.

The name "K4" was derived from its Lloyd's unlimited rating, and was carried in a prom ...

'': 19 August 1939 – 141.74 mph (228.11 km/h)

Production and individual engine history

Production summary

Individual history table

Applications

;Aircraft

* Supermarine S.6

* Supermarine S.6A

* Supermarine S.6B

;Cars

*''

;Aircraft

* Supermarine S.6

* Supermarine S.6A

* Supermarine S.6B

;Cars

*''Campbell-Railton Blue Bird

The Campbell-Railton Blue Bird was Sir Malcolm Campbell's final land speed record car.

His previous Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird of 1931 was rebuilt significantly. The overall layout and the simple twin deep chassis rails remained, but lit ...

''

*''Thunderbolt

A thunderbolt or lightning bolt is a symbolic representation of lightning when accompanied by a loud thunderclap. In Indo-European mythology, the thunderbolt was identified with the 'Sky Father'; this association is also found in later Hel ...

''

;Boats

*''Blue Bird K3

''Blue Bird K3'' is a hydroplane powerboat commissioned in 1937 by Sir Malcolm Campbell, to rival the Americans' efforts in the fight for the world water speed record. She set three world water speed records, first on Lake Maggiore in Septem ...

''

*''Blue Bird K4

''Blue Bird K4'' was a powerboat commissioned in 1939 by Sir Malcolm Campbell, to rival the Americans' efforts in the fight for the world water speed record.

The name "K4" was derived from its Lloyd's unlimited rating, and was carried in a prom ...

''

*'' Miss England II''

*''Miss England III

''Miss England III'' was the last of a series of speedboats used by Henry Segrave and Kaye Don to contest world water speed records in the 1920s and 1930s. She was the first craft in the Lloyds Unlimited Group of high-performance speedboats cre ...

''

Engines on display

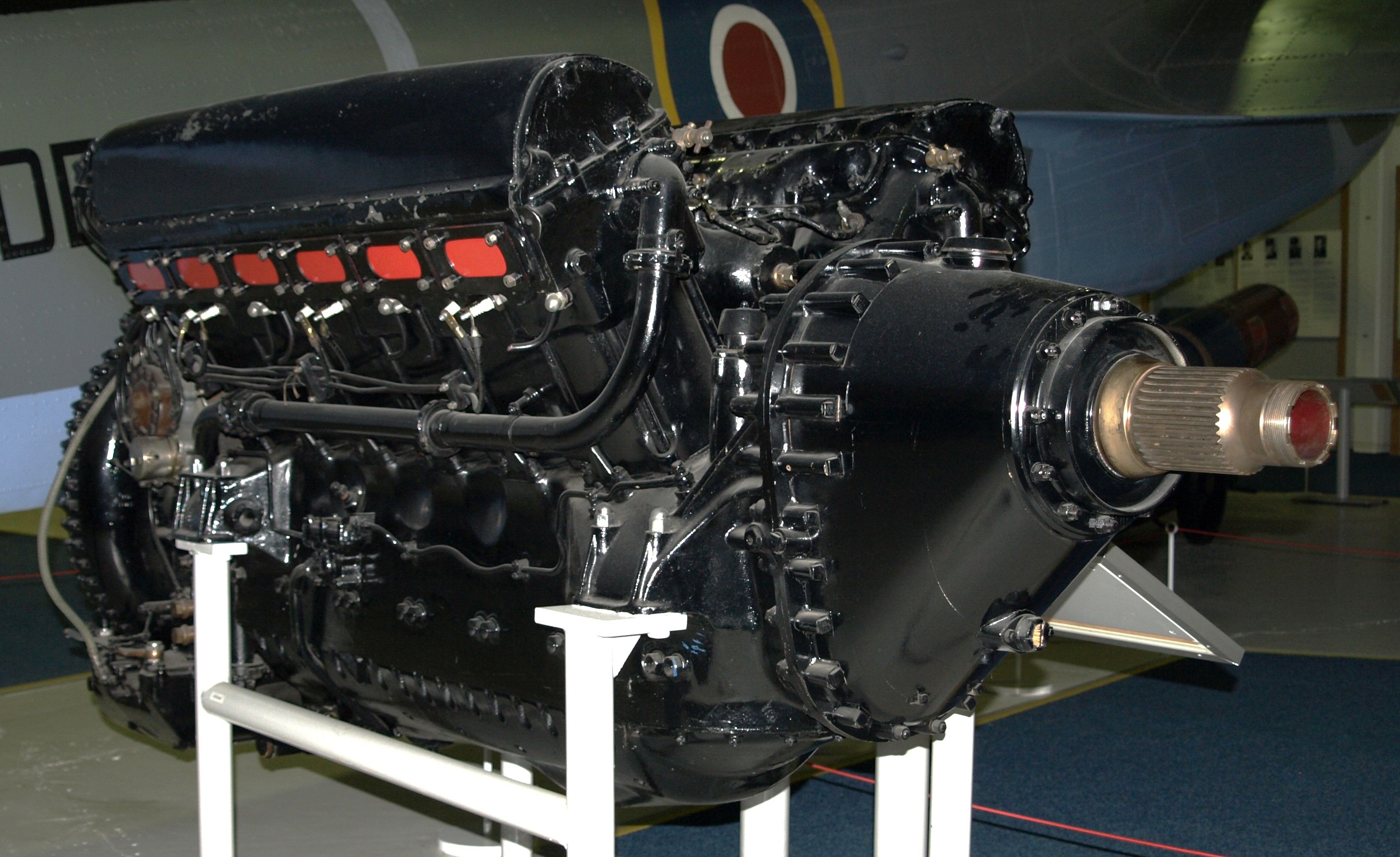

Royal Air Force Museum London

The Royal Air Force Museum London (also commonly known as the RAF Museum) is located on the former Hendon Aerodrome. It includes five buildings and hangars showing the history of aviation and the Royal Air Force. It is part of the Royal Air Fo ...

at Hendon has a Rolls-Royce R on display (museum number 65E1139) that came to the museum in November 1965 from RAF Cranwell

Royal Air Force Cranwell or more simply RAF Cranwell is a Royal Air Force station in Lincolnshire, England, close to the village of Cranwell, near Sleaford. Among other functions, it is home to the Royal Air Force College (RAFC), which trai ...

. According to the museum's records, before that it was with George Eyston as one of '' Thunderbolt's'' record engines. Its data plate states that it is ''R25'' under Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

contract number A106961 which makes it the second 1931 race engine delivered to RAF Calshot.

;''R27''

The London Science Museum has an R engine on display which is catalogued as a stand-alone item, inventory number 1948-310. This is ''R27'', the second sprint engine prepared for the successful air speed record attempt, and later used in ''Thunderbolt''. The Science Museum also has S.6B, ''S1595'', (winner of the 1931 race and the final air speed record aircraft) on display.

;''R37''

The Filching Manor Motor Museum has ''R37'' which is destined to be fitted in its restoration of the ''Blue Bird K3'' water speed record boat.

These three engines are the only ones listed by the British Aircraft Preservation Council/Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. The Solent Sky

Solent Sky is an aviation museum in Southampton, Hampshire, previously known as Southampton Hall of Aviation.

It depicts the history of aviation in Southampton, the Solent area and Hampshire. There is special focus on the Supermarine aircraft c ...

museum's S.6A, ''N248,'' (a competing aircraft in the 1929 race as an S.6, and stand-by for the 1931 race, modified as an S.6A) does not contain an R engine.Ellis 2004, p. 75.

Specifications (R – 1931)

See also

References

Footnotes

Citations

Bibliography

*Ellis, Ken. ''Wrecks and Relics - 19th Edition'', Midland Publishing, Hinckley, Leicestershire. 2004. *Eves, Edward. ''The Schneider Trophy Story''. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 2001. . *Gunston, Bill. ''World Encyclopaedia of Aero Engines''. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens Limited, 1989. *Gunston, Bill. ''Development of Piston Aero Engines''. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens Limited, 2006. *Holter, Steve. ''Leap into Legend''. Wilmslow, Cheshire, UK: Sigma Press, 2002. *Jennings, Charles. ''The Fast Set''. London, UK: Abacus, Little, Brown Book Group, 2004. *Lumsden, Alec. ''British Piston Engines and their Aircraft''. Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. . *Price, Alfred. ''The Spitfire Story'' Second edition. London, UK: Arms and Armour Press Ltd., 1986. . *Rubbra, A.A. ''Rolls-Royce Piston Aero Engines – a designer remembers'' Historical Series (16) Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, 1990.External links

1929 Schneider Trophy, original footage and soundtrack

''Note:'' Requires

Flash Video

Flash Video is a container file format used to deliver digital video content (e.g., TV shows, movies, etc.) over the Internet using Adobe Flash Player version 6 and newer. Flash Video content may also be embedded within SWF files. There ar ...

to view.Campbell-Railton Blue Bird, ''The Motor'', 10 January 1933 – Design details

{{featured article R 1920s aircraft piston engines