Rock reliefs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A rock relief or rock-cut relief is a

A rock relief or rock-cut relief is a

At

At

The large carved rock relief, typically placed high beside a road, and near a source of water, is a common medium in Persian art, mostly used to glorify the king and proclaim Persian control over territory. It begins with

The large carved rock relief, typically placed high beside a road, and near a source of water, is a common medium in Persian art, mostly used to glorify the king and proclaim Persian control over territory. It begins with

Although carving into solid rock is more a feature of Indian sculpture than of any other culture, most Indian sculptures fall outside the strict definition of rock reliefs because they are either fully detached statues, or are reliefs within rock-cut or natural caves, or temples entirely cut from the living rock. In the former group are many colossal

Although carving into solid rock is more a feature of Indian sculpture than of any other culture, most Indian sculptures fall outside the strict definition of rock reliefs because they are either fully detached statues, or are reliefs within rock-cut or natural caves, or temples entirely cut from the living rock. In the former group are many colossal

File:Trimurti, Cave No. 1, Elephanta Caves - 1.jpg, Inside a cave temple at Elephanta,

Buddhism, originating in India, took the traditions of cave and

Buddhism, originating in India, took the traditions of cave and

File:Buda de Avukana - 03.jpg,

The Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman

Pre-Columbian rock reliefs, mostly using a low relief, include those at

Pre-Columbian rock reliefs, mostly using a low relief, include those at

Lion Monument, Lucerne

''All About Switzerland'' travelguide. Accessed 13 November 2015

Image:IvrizRelief.JPG, The Hittite İvriz relief; King Warpalawas (right) before the god Tarhunzas

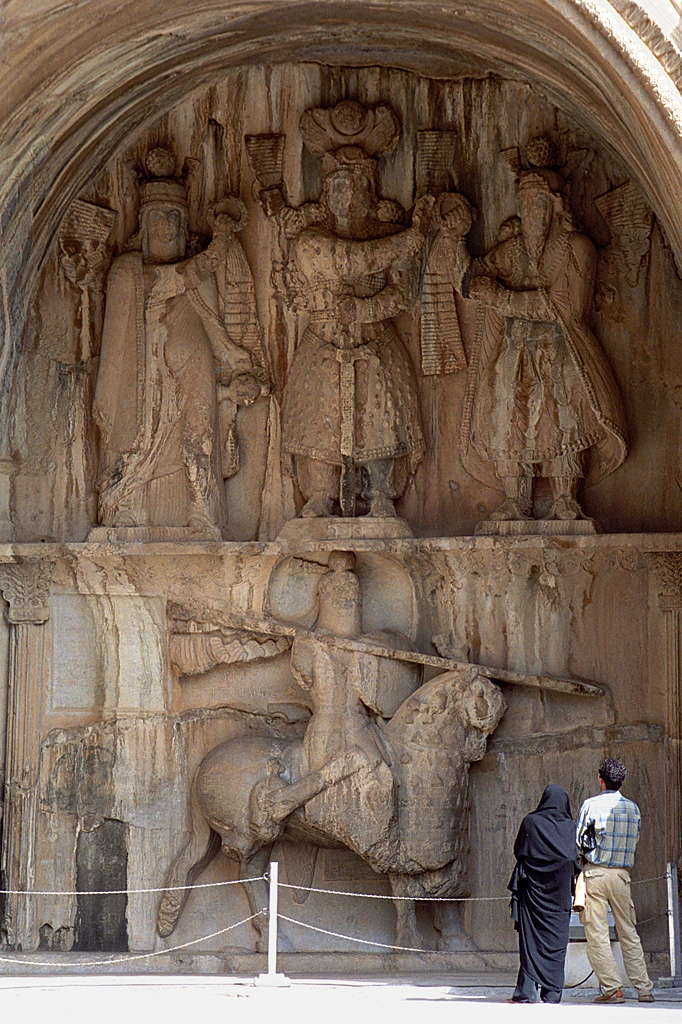

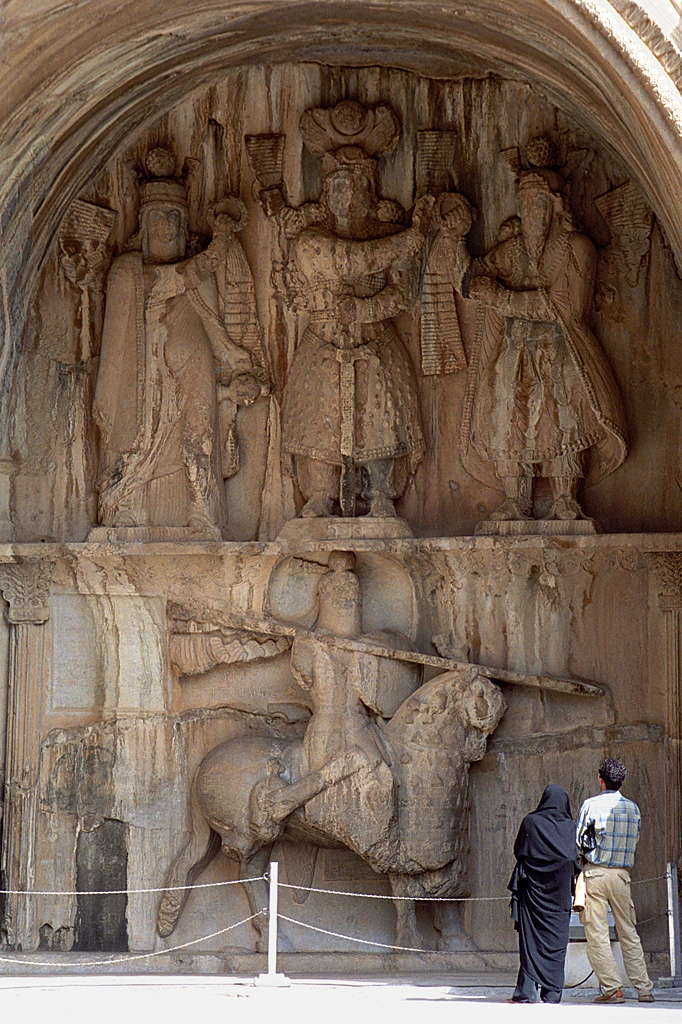

File:Naqshe Rajab Darafsh Ordibehesht 93 (2).JPG, Sassanian investiture relief of

google books

*Canepa, Matthew P., "Topographies of Power, Theorizing the Visual, Spatial and Ritual Contexts of Rock Reliefs in Ancient Iran", in Harmanşah (2014)

google books

*Cotterell, Arthur (ed), ''The Penguin Encyclopedia of Classical Civilizations'', 1993, Penguin, *Downey, S.B., "Art in Iran, iv., Parthian Art", ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', 1986

Online text

*Harle, J.C., ''The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent'', 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, *Harmanşah, Ömür (2014a), "Rock Reliefs are Never Finished", in ''Place, Memory, and Healing: An Archaeology of Anatolian Rock Monuments'', 2014, Routledge, , 9781317575726

google books

*Harmanşah, Ömür (ed) (2014), ''Of Rocks and Water: An Archaeology of Place'', 2014, Oxbow Books, , 9781782976745 *Herrmann, G, and Curtis, V.S., "Sasanian Rock Reliefs", ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', 2002

Online text

*Jessup, Helen Ibbetson, ''Art and Architecture of Cambodia'', 2004, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), *Kreppner, Florian Janoscha, "Public Space in Nature: The Case of Neo-Assyrian Rock-Reliefs", ''Altorientalische Forschungen'', 29/2 (2002): 367–383

online at Academia.edu

*Ledering, Joan

http://www.livius.org *Luschey, Heinz, "Bisotun ii. Archeology", ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', 2013

Online text

* Rawson, Jessica (ed). ''The British Museum Book of Chinese Art'', 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, * Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L. & Soper A., ''The Art and Architecture of China'', Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675 *Spink, Walter M., ''Ajanta: History and Development Volume 5: Cave by Cave'', 2006, Brill, Leiden,

online

{{Authority control * Types of sculpture

A rock relief or rock-cut relief is a

A rock relief or rock-cut relief is a relief sculpture

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

carved on solid or "living rock" such as a cliff, rather than a detached piece of stone. They are a category of rock art

In archaeology, rock art is human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type also m ...

, and sometimes found as part of, or in conjunction with, rock-cut architecture

Rock-cut architecture is the creation of structures, buildings, and sculptures by excavating solid rock where it naturally occurs. Intensely laborious when using ancient tools and methods, rock-cut architecture was presumably combined with quarry ...

. However, they tend to be omitted in most works on rock art, which concentrate on engravings and paintings by prehistoric peoples. A few such works exploit the natural contours of the rock and use them to define an image, but they do not amount to man-made reliefs. Rock reliefs have been made in many cultures throughout human history, and were especially important in the art of the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

. Rock reliefs are generally fairly large, as they need to be in order to have an impact in the open air. Most of those discussed here have figures that are over life-size, and in many the figures are multiples of life-size.

Stylistically they normally relate to other types of sculpture from the culture and period concerned, and except for Hittite and Persian examples they are generally discussed as part of that wider subject. Reliefs on near-vertical surfaces are most common, but reliefs on essentially horizontal surfaces are also found. The term typically excludes relief carvings inside caves, whether natural or themselves man-made, which are especially found in Indian rock-cut architecture

Indian rock-cut architecture is more various and found in greater abundance in that country than any other form of rock-cut architecture around the world. Rock-cut architecture is the practice of creating a structure by carving it out of solid n ...

. Natural rock formations made into statues or other sculpture in the round, most famously at the Great Sphinx of Giza

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a limestone statue of a reclining sphinx, a mythical creature with the head of a human, and the body of a lion. Facing directly from west to east, it stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, ...

, are also usually excluded. Reliefs on large boulders left in their natural location, like the Hittite İmamkullu relief, are likely to be included, but smaller boulders may be called stela

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), wh ...

e or carved orthostat

This article describes several characteristic architectural elements typical of European megalithic (Stone Age) structures.

Forecourt

In archaeology, a forecourt is the name given to the area in front of certain types of chamber tomb. Forecourts ...

s. Many or most ancient reliefs were probably originally painted, over a layer of plaster; in some traces of this remain.

The first requirement for a rock relief is a suitable face of stone; a near-vertical cliff minimizes the work required, otherwise a sloping rock face is often cut back to give a vertical area to carve. Most of the ancient Near East was well supplied with hills and mountains offering many cliff faces. An exception was the land of Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of ...

, where all stone had to be imported over considerable distances, and so the art of Mesopotamia

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the record from early hunter-gatherer societies (8th millennium BC) on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Ag ...

only features rock relief around the edges of the region. The Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

and ancient Persians were the most prolific makers of rock reliefs in the Near East.

The form is adopted by some cultures and ignored by others. In the many commemorative stelae of Nahr el-Kalb, 12 kilometres north of Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, successive imperial rulers have carved memorials and inscriptions. The Ancient Egyptian, Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

and Neo-Babylonian

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and be ...

rulers include relief imagery in their monuments, while the Roman and Islamic rulers do not, nor more modern ones (who erect slabs of stone carved elsewhere and fitted to the rock).

Egypt

Although prehistoric engravedpetroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s are common in Egypt, in general the form is not a very common one in Ancient Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculpture ...

, and only possible in some parts of the country, generally those away from the main centres of population, as Abu Simbel was. There are a group of figures surrounding an image of Mentuhotep II

Mentuhotep II ( egy, Mn- ṯw- ḥtp, meaning " Mentu is satisfied"), also known under his prenomen Nebhepetre ( egy, Nb- ḥpt- Rˁ, meaning "The Lord of the rudder is Ra"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh ...

, who died in 2010 BC and was the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom.

Before they were cut away and moved, the colossal figures outside the Abu Simbel temples

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel ( ar, أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is situated on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about s ...

were very high reliefs. Other sculpture outside temples cut into the rock qualifies as rock reliefs. The reliefs at Nahr el-Kalb commemorate Rameses II

Ramesses II ( egy, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded as ...

, and are at the furthest reach of his empire (indeed beyond the area he reliably controlled) in modern Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

.

Hittites and Assyrians

The Hittites were important producers of rock reliefs, which form a relatively large part of the few artistic remains they have left. TheKarabel relief

The Hittite / Luwian Karabel relief is a rock relief in the pass of the same name, between Torbalı and Kemalpaşa, about 20 km from Izmir in Turkey. Rock reliefs are a prominent aspect of Hittite art.

Description

The monument o ...

of a king was seen by Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, who mistakenly thought it showed the Egyptian Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

Sesostris

Sesostris ( grc-gre, Σέσωστρις), also transliterated as Sesoösis, or Sesonchosis, is the name of a legendary king of ancient Egypt who, according to Herodotus, led a military expedition into parts of Europe. Tales of Sesostris are pro ...

. This, like many Hittite reliefs, is near a road, but actually rather hard to see from the road. There are more than a dozen sites, most over 1000 metres in elevation, overlooking plains, and typically near water. These perhaps were placed with an eye to the Hittite's relation to the landscape rather than merely as rulers' propaganda, signs of "landscape control", or border markers, as has often been thought. They are often at sites with a sacred significance both before and after the Hittite period, and apparently places where the divine world was considered as sometimes breaking through to the human one.

At

At Yazılıkaya

:'' Yazılıkaya, Eskişehir, also called Midas City, is a village with Phrygian ruins.''

Yazılıkaya ( tr, Inscribed rock) was a sanctuary of Hattusa, the capital city of the Hittite Empire, today in the Çorum Province, Turkey. Rock reliefs ar ...

, just outside the capital of Hattusa

Hattusa (also Ḫattuša or Hattusas ; Hittite: URU''Ḫa-at-tu-ša'', Turkish: Hattuşaş , Hattic: Hattush) was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, within the great loop of ...

, a series of reliefs of Hittite gods in procession decorate open-air "chambers" made by adding barriers among the natural rock formations. The site was apparently a sanctuary, and possibly a burial site, for the commemoration of the ruling dynasty's ancestors. It was perhaps a private space for the dynasty and a small group of the elite, unlike the more public wayside reliefs. The usual form of these is to show royal males carrying weapons, usually holding a spear, carrying a bow over their shoulder, with a sword at their belt. They have attributes associated with divinity, and so are shown as "god-warriors".

The Assyrians probably took the form from the Hittites; the sites chosen for their 49 recorded reliefs often also make little sense if "signalling" to the general population was the intent, being high and remote, but often near water. The Neo-Assyrians recorded in other places, including metal reliefs on the Balawat Gates

The Balawat Gates are three sets of decorated bronze bands that had adorned the main doors of several buildings at Balawat (ancient Imgur-Enlil), dating to the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) and Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BC). The ...

showing them being made, the carving of rock reliefs, and it has been suggested that the main intended audience was the gods, the reliefs and the inscriptions that often accompany them being almost of the nature of a "business report" submitted by the ruler. A canal system built by the Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

king Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynas ...

(reigned 704–681 BC) to supply water to Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ba ...

was marked by a number of reliefs showing the king with gods. Other reliefs at the Tigris tunnel

The so-called Tigris tunnel is a cave approximately 50 miles north of Diyarbakır in Turkey. It has a length of about . The Berkilin Cay flows through this cave. It forms a source of the Tigris, but not the main one, although the exit was long bel ...

, a cave in modern Turkey believed to be the source of the river Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, are "almost inaccessible and invisible for humans". Probably built by Sennacherib's son Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of hi ...

, Shikaft-e Gulgul

Shikaft-e Golgol-Gulgul (or Gulgulcave or Golgolcave) site is an Assyrian rock relief and inscription located in the vicinity of Gulgul, گل گل a village near Mount Pushta-e Kuh at Ilam in Iran. It was discovered by Louis Vanden Berghe (Ghent ...

is a late example in modern Iran, apparently related to a military campaign.

Persia

The large carved rock relief, typically placed high beside a road, and near a source of water, is a common medium in Persian art, mostly used to glorify the king and proclaim Persian control over territory. It begins with

The large carved rock relief, typically placed high beside a road, and near a source of water, is a common medium in Persian art, mostly used to glorify the king and proclaim Persian control over territory. It begins with Lullubi

Lullubi, Lulubi ( akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈: ''Lu-lu-bi'', akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈𒆠: ''Lu-lu-biki'' "Country of the Lullubi"), more commonly known as Lullu, were a group of tribes during the 3rd millennium BC, from a region known as ''Lulubum'', now the Sha ...

and Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

ite rock reliefs, such as those at Kul-e Farah

Kul-e Farah (Henceforth KF) is an archaeological site and open air sanctuary situated in the Zagros mountain valley of Izeh/Mālamir, in south-western Iran, around 800 meters over sea level. Six Elamite rock reliefs are located in a small gorge ...

and Eshkaft-e Salman

Eshkaft-e Salman or ''Shekaft-e Salman''

Location

On the southwest side of the valley, 2.5 km from the town center of Izeh, southwest Iran, is the majestic “''romantic grotto''” of Shekaft-e Salman (“Salomon’s Cave”) where a ...

in southwest Iran, and continues under the Assyrians. The Behistun relief and inscription, made around 500 BC for Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

, is on a far grander scale, reflecting and proclaiming the power of the Achaemenid empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

. Persian rulers commonly boasted of their power and achievements, until the Muslim conquest removed imagery from such monuments; much later there was a small revival under the Qajar dynasty

The Qajar dynasty (; fa, دودمان قاجار ', az, Qacarlar ) was an IranianAbbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3 royal dynasty of Turkic origin ...

.

Behistun is unusual in having a large and important inscription, which like the Egyptian Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Anci ...

repeats its text in three different languages, here all using cuneiform script

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-s ...

: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a later form of Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

). This was important in the modern understanding of these languages. Other Persian reliefs generally lack inscriptions, and the kings involved often can only be tentatively identified. The problem is helped in the case of the Sassanids by their custom of showing a different style of crown for each king, which can be identified from their coins.

Naqsh-e Rustam

Naqsh-e Rostam ( lit. mural of Rostam, fa, نقش رستم ) is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 12 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into t ...

is the necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

of the Achaemenid dynasty

The Achaemenid dynasty (Old Persian: ; Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) was an ancient Persian royal dynasty that ruled the Achaemenid Empire, an Iranian empire that stretched from Egypt and Southeastern Europe in the west to the Ind ...

(500–330 BC), with four large tombs cut high into the cliff face. These have mainly architectural decoration, but the facades include large panels over the doorways, each very similar in content, with figures of the king being invested by a god, above a zone with rows of smaller figures bearing tribute, with soldiers and officials. The three classes of figures are sharply differentiated in size. The entrance to each tomb is at the centre of each cross, which opens onto a small chamber, where the king lay in a sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

. The horizontal beam of each of the tomb's facades is believed to be a replica of the entrance of the palace at Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

.

Only one has inscriptions and the matching of the other kings to tombs is somewhat speculative; the relief figures are not intended as individualized portraits. The third from the left, identified by an inscription, is the tomb of Darius I the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

(''c.'' 522–486 BC). The other three are believed to be those of Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

(''c.'' 486–465 BC), Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

He may have been the " Artas ...

(''c.'' 465–424 BC), and Darius II

Darius II ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ), also known by his given name Ochus ( ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 423 BC to 405 or 404 BC.

Artaxerxes I, who died in 424 BC, was followed by h ...

(''c.'' 423–404 BC) respectively. A fifth unfinished one might be that of Artaxerxes III, who reigned at the longest two years, but is more likely that of Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dariu ...

(''c.'' 336–330 BC), last of the Achaemenid dynasts. The tombs were looted following the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

.

Well below the Achaemenid tombs, near ground level, are rock reliefs with large figures of Sassanian

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

kings, some meeting gods, others in combat. The most famous shows the Sassanian king Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, Šābuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardas ...

on horseback, with the Roman Emperor Valerian bowing to him in submission, and Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab ( la, Marcus Julius Philippus "Arabs"; 204 – September 249) was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. He was born in Aurantis, Arabia, in a city situated in modern-day Syria. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip, ...

(an earlier emperor who paid Shapur tribute) holding Shapur's horse, while the dead Emperor Gordian III

Gordian III ( la, Marcus Antonius Gordianus; 20 January 225 – February 244) was Roman emperor from 238 to 244. At the age of 13, he became the youngest sole emperor up to that point (until Valentinian II in 375). Gordian was the son of Anto ...

, killed in battle, lies beneath it (other identifications have been suggested). This commemorates the Battle of Edessa

The Battle of Edessa took place between the armies of the Roman Empire under the command of Emperor Valerian and Sasanian forces under Shahanshah (King of the Kings) Shapur I in 260. The Roman army was defeated and captured in its entirety ...

in 260 AD, when Valerian became the only Roman Emperor who was captured as a prisoner of war, a lasting humiliation for the Romans. The placing of these reliefs clearly suggests the Sassanid intention to link themselves with the glories of the earlier Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

. There are three further Achaemenid royal tombs with similar reliefs at Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

, one unfinished.

The seven Sassanian reliefs, whose approximate dates range from 225 to 310 AD, show subjects including investiture scenes and battles. The earliest relief at the site is Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

ite, from about 1000 BC. About a kilometre away is Naqsh-e Rajab, with a further four Sassanid rock reliefs, three celebrating kings and one a high priest. Another important Sassanid site is Taq Bostan

Taq-e Bostan ( fa, طاق بستان, ) is a site with a series of large rock reliefs from the era of the Sassanid Empire of Persia (Iran), carved around the 4th century CE.

This example of Persian Sassanid art is located 5 km from the ...

with several reliefs including two royal investitures and a famous figure of a cataphract

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalryman that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

The English word derives from the Greek ' (plural: '), literally meaning "armored" or ...

or Persian heavy cavalryman, about twice life size, probably representing the king Khosrow Parviz

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king ( shah) of Iran, ruling f ...

mounted on his favourite horse Shabdiz; the pair continued to be celebrated in later Persian literature. Firuzabad, Fars

Firuzabad ( fa, فيروزآباد or Piruzabad, also Romanized as Fīrūzābād; Middle Persian: Gōr or Ardashir-Khwarrah, literally "The Glory of Ardashir"; also Shahr-e Gūr ) is a city and capital of Firuzabad County, Fars Province, Iran. At ...

and Bishapur

Bishapur (Middle Persian: ''Bay-Šāpūr''; fa, بیشاپور}, ''Bishâpûr'') was an ancient city in Sasanid Persia (Iran) on the ancient road between Persis and Elam. The road linked the Sassanid capitals Estakhr (very close to Persepolis ...

have groups of Sassanian reliefs, the former including the oldest, a large battle scene, now badly worn. At Barm-e Delak

Barm-e Delak ( fa, برمدلک), is a site of a Sasanian rock relief located about 10 km southeast of Shiraz, in the Pars Province of Iran. The rock relief was known as Bahram-e Dundalk in Middle Persian, which means ''Bahram's heart''.

...

a king offers a flower to his queen.

Sassanian reliefs are concentrated in the first 80 years of the dynasty, though one important set are 6th-century, and at relatively few sites, mostly in the Sassanid heartland. The later ones in particular suggest that they draw on a now-lost tradition of similar reliefs in palaces in stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

. The rock reliefs were probably coated in plaster and painted.

The rock reliefs of the preceding Persian Seleucids and Parthians Parthian may be:

Historical

* A demonym "of Parthia", a region of north-eastern of Greater Iran

* Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD)

* Parthian language, a now-extinct Middle Iranian language

* Parthian shot, an archery skill famously employed by ...

are generally smaller and more crude, and not all direct royal commissions as the Sassanid ones clearly were. At Behistun an earlier relief including a lion was adapted into a reclining Herakles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive ...

in a fully Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

style; he reclines on a lion skin. This was only uncovered below rubble relatively recently; an inscription dates it to 148 BC. Other reliefs in Iran include the Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyri ...

king in shallow relief at Shikaft-e Gulgul

Shikaft-e Golgol-Gulgul (or Gulgulcave or Golgolcave) site is an Assyrian rock relief and inscription located in the vicinity of Gulgul, گل گل a village near Mount Pushta-e Kuh at Ilam in Iran. It was discovered by Louis Vanden Berghe (Ghent ...

; not all sites with Persian reliefs are in modern Iran. Qajar reliefs include a large and lively panel showing hunting at the royal hunting-ground of Tangeh Savashi, and a panel, still largely with its colouring intact, at Taq Bostan showing the shah seated with attendants.

The standard catalogue of pre-Islamic Persian reliefs lists the known examples (as at 1984) as follows: Lullubi

Lullubi, Lulubi ( akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈: ''Lu-lu-bi'', akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈𒆠: ''Lu-lu-biki'' "Country of the Lullubi"), more commonly known as Lullu, were a group of tribes during the 3rd millennium BC, from a region known as ''Lulubum'', now the Sha ...

#1–4; Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

#5–19; Assyrian #20–21; Achaemenid #22–30; Late/Post-Achaemenid and Seleucid #31–35; Parthian #36–49; Sasanian #50–84; others #85–88.

India

Although carving into solid rock is more a feature of Indian sculpture than of any other culture, most Indian sculptures fall outside the strict definition of rock reliefs because they are either fully detached statues, or are reliefs within rock-cut or natural caves, or temples entirely cut from the living rock. In the former group are many colossal

Although carving into solid rock is more a feature of Indian sculpture than of any other culture, most Indian sculptures fall outside the strict definition of rock reliefs because they are either fully detached statues, or are reliefs within rock-cut or natural caves, or temples entirely cut from the living rock. In the former group are many colossal Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

figures of tirthankara

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English: literally a ' ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the '' dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a '' tirtha'', which is a fordable pass ...

, and in the later Hindu and Buddhist works at the Elephanta Caves

The Elephanta Caves are a collection of cave temples predominantly dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva. They are on Elephanta Island, or ''Gharapuri'' (literally "the city of caves"), in Mumbai Harbour, east of Mumbai in the Indian state of ...

, Ajanta Caves

The Ajanta Caves are approximately thirty rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments dating from the second century BCE to about 480 CE in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state in India. The caves include paintings and rock-cut sculptures de ...

, Ellora

Ellora is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra, India. It is one of the largest rock-cut Hindu temple cave complexes in the world, with artwork dating from the period 600–1000 CE., Quote: "These 34 ...

, the Aurangabad Caves

The Aurangabad caves are twelve rock-cut Buddhist shrines located on a hill running roughly east to west, close to the city of Aurangabad, Maharashtra. The first reference to the Aurangabad Caves is in the great chaitya of Kanheri Caves. The Aur ...

, and most of the Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram. Especially at Ajanta, there are many rock reliefs in the open, around the entrances to the caves, either part of the original designs or votive sculptures added later by individual patrons.

However, there are a number of significant rock reliefs in India, with the ''Descent of the Ganges

''Descent of the Ganges'', known locally as ''Arjuna's Penance'', is a monument at Mamallapuram, on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal, in the Chengalpattu district of the state of Tamil Nadu, India. Measuring , it is a giant open-air roc ...

'' at Mahabalipuram

Mamallapuram, also known as Mahabalipuram, is a town in Chengalpattu district in the southeastern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, best known for the UNESCO World Heritage Site of 7th- and 8th-century Hindu Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram. It ...

the best known and perhaps the most impressive. This is a large 7th-century Hindu scene with many figures that uses the form of the rock to shape the image. The Anantashayi Vishnu is an early 9th-century horizontal relief of the reclining Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

god Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" withi ...

in Orissa

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of S ...

, measuring in length, cut into a flat bed of rock. while the largest standing image is the Gommateshwara statue

The Gommateshwara statue is a high monolithic statue on Vindhyagiri Hill in the town of Shravanbelagola in the Indian state of Karnataka. Carved of a single block of granite, it is one of the tallest monolithic statues in the world second only ...

in Southern India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana, as well as the union territ ...

. At Unakoti, Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the ea ...

there is an 11th-century group of reliefs related to Shiva

Shiva (; sa, शिव, lit=The Auspicious One, Śiva ), also known as Mahadeva (; Help:IPA/Sanskrit, ɐɦaːd̪eːʋɐ, or Hara, is one of the Hindu deities, principal deities of Hinduism. He is the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one o ...

, and at Hampi

Hampi or Hampe, also referred to as the Group of Monuments at Hampi, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Hampi town, Vijayanagara district, east-central Karnataka, India.

Hampi was the capital of the Vijayanagara Empire in the 14th&n ...

scenes from the Ramayana

The ''Rāmāyana'' (; sa, रामायणम्, ) is a Sanskrit epic composed over a period of nearly a millennium, with scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text ranging from the 8th to 4th centuries BCE, and later stages ...

. Several sites, such as Kalugumalai

Kalugumalai is a panchayat town in Kovilpatti Taluk of Thoothukudi district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Kalugumalai is 21 km and 22 km from Kovilpatti and Sankarankovil respectively. The place houses the rockcut Kalugasalamoorth ...

and the Samanar Hills

Samanar Hills, also known as Samanar Malai or Amanarmalai or Melmalai, is a rocky stretch of hills located near Keelakuyilkudi village, west of Madurai city, Tamil Nadu, India. They stretch east–west over 3 kilometers towards Muthupatti villa ...

in Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil language ...

, have Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

reliefs, mostly of meditating tirthankara

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English: literally a ' ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the '' dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a '' tirtha'', which is a fordable pass ...

s.

Trimurti

The Trimūrti (; Sanskrit: त्रिमूर्ति ', "three forms" or "trinity") are the trinity of supreme divinity in Hinduism, in which the cosmic functions of creation, maintenance, and destruction are personified as a triad of ...

Shiva flanked by the ''dvarapalas'', 5-6th century

File:Arjuna’s Penance at Mamallapuram.jpg, ''Descent of the Ganges

''Descent of the Ganges'', known locally as ''Arjuna's Penance'', is a monument at Mamallapuram, on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal, in the Chengalpattu district of the state of Tamil Nadu, India. Measuring , it is a giant open-air roc ...

'' at Mahabalipuram

Mamallapuram, also known as Mahabalipuram, is a town in Chengalpattu district in the southeastern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, best known for the UNESCO World Heritage Site of 7th- and 8th-century Hindu Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram. It ...

, 7th century

File:Bishnu AnantaShayan, Saraang.jpg, The sleeping Anantashayi Vishnu, 9th century

File:Tirumalai Neminatha Statue.jpg, Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

relief of Neminatha

Neminatha, also known as Nemi and Arishtanemi, is the twenty-second ''tirthankara'' (ford-maker) in Jainism. Along with Mahavira, Parshvanatha and Rishabhanatha, Neminatha is one of the twenty four ''tirthankaras'' who attract the most devot ...

at Tirumalai, Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil language ...

, c. 12th century

Buddhism

Buddhism, originating in India, took the traditions of cave and

Buddhism, originating in India, took the traditions of cave and rock-cut architecture

Rock-cut architecture is the creation of structures, buildings, and sculptures by excavating solid rock where it naturally occurs. Intensely laborious when using ancient tools and methods, rock-cut architecture was presumably combined with quarry ...

to other parts of Asia, including the creation of rock reliefs. In these the emphasis shifted to religious subject matter; in earlier reliefs deities had normally appeared only to show their approval of the ruler. The colossal Buddha figures are nearly all in very high relief, only still attached to the rock face at the rear. Several have or had "image houses", or buildings enclosing them, which meant that they could normally only be seen very close up, and the impressive view from further back was lost to pilgrims.

In Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

colossal Buddha figures include the Avukana Buddha statue

The Avukana statue is a standing statue of the Buddha near Kekirawa in North Central Sri Lanka. The statue, which has a height of more than , was carved out of a large granite rock face during the 5th century. It depicts a variation of the Abhay ...

, 5th century and almost free-standing, with only a narrow strip at the back still connecting it to the cliff, and the four 12-century Buddha figures at Gal Vihara; the brick foundations for image houses can be seen here. The seven 10th-century figures at Buduruvagala

Buduruwagala is an ancient buddhist temple in Sri Lanka. The complex consists of seven statues and belongs to the Mahayana school of thought. The statues date back to the 10th century. The gigantic Buddha statue still bears traces of its original s ...

are in much lower relief. There are very lively elephants carved around a temple pool at Isurumuniya. Of the colossal lion gateway to the hill-palace at Sigiriya

Sigiriya or Sinhagiri (''Lion Rock'' si, සීගිරිය, ta, சிகிரியா/சிங்ககிரி, pronounced see-gi-ri-yə) is an ancient rock fortress located in the northern Matale District near the town of Dambulla ...

, only the paws remain, the head having fallen off at some point.

The three famous ancient Buddhist sculptural sites in China are the Mogao Caves

The Mogao Caves, also known as the Thousand Buddha Grottoes or Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, form a system of 500 temples southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu p ...

, Longmen Grottoes

The Longmen Grottoes () or Longmen Caves are some of the finest examples of Chinese Buddhist art. Housing tens of thousands of statues of Shakyamuni Buddha and his disciples, they are located south of present-day Luoyang in Henan province ...

(672–673 for the main group) and Yungang Grottoes

The Yungang Grottoes (), formerly the Wuzhoushan Grottoes (), are ancient Chinese Buddhist temple grottoes near the city of Datong in the province of Shanxi. They are excellent examples of rock-cut architecture and one of the three most famous anc ...

(460–535), all of which have colossal Buddha statues in very high relief, cut back into huge niches in the cliff, though the largest figure at Mogao is still enclosed by a wooden image house superstructure in front of it; this is also thought to be a portrait of the reigning empress Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian (17 February 624 – 16 December 705), personal name Wu Zhao, was the ''de facto'' ruler of the Tang dynasty from 665 to 705, ruling first through others and then (from 690) in her own right. From 665 to 690, she was first empres ...

. One of the Longmen figures is effectively in a man-made cave, but can be seen from outside through a large window opened in the outer face (see gallery). Smaller rock-cut sculptures and paintings decorate the cave temples at these sites.

The Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

Leshan Giant Buddha

The Leshan Giant Buddha () is a tall stone statue, built between 713 and 803 (during the Tang dynasty). It is carved out of a cliff face of Cretaceous red bed sandstones that lies at the confluence of the Min River and Dadu River in the south ...

, the largest of all, was built with a superstructure covering it, which was destroyed by the Mongols. Such large figures were a novelty in Chinese art, and adapted conventions from further west. The Dazu Rock Carvings include scenes with unusually large numbers of figures, such as a famous and large scene of the Buddhist Judgement of Souls. These are set back into the cliff and the shelter has enabled them to retain their bright colours. Other Chinese Buddhist cave sites with external rock reliefs include Lingyin Temple

Lingyin Temple () is a Buddhist temple of the Chan sect located north-west of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. The temple's name is commonly literally translated as Temple of the Soul's Retreat. It is one of the largest and wealthiest Buddhis ...

with many small reliefs, and the Maijishan Grottoes

The Maijishan Grottoes (), formerly romanized as Maichishan, are a series of 194 caves cut in the side of the hill of Maijishan in Tianshui, Gansu Province, northwest China.

This example of rock cut architecture contains over 7,200 Buddhist s ...

with a main colossal group; unusually for figures of such a size, they are in bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

.

The Bamiyan Buddha figures were two standing Buddha figures of the 6th century in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

which were destroyed by the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state (polity), state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic fundamentalist, m ...

in 2001; they probably were one of the immediate influences on the Chinese sites further east on the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

. In Japan the Nihon-ji temple includes a colossal seated Buddha completed in 1783, 31 metres tall. Japanese "Great Buddha" statues are called "daibutsu

or 'giant Buddha' is the Japanese term, often used informally, for large statues of Buddha. The oldest is that at Asuka-dera (609) and the best-known is that at Tōdai-ji in Nara (752). Tōdai-ji's daibutsu is a part of the UNESCO World Herit ...

", but most are in bronze.

Sites elsewhere include Kbal Spean near Angkor

Angkor ( km, អង្គរ , 'Capital city'), also known as Yasodharapura ( km, យសោធរបុរៈ; sa, यशोधरपुर),Headly, Robert K.; Chhor, Kylin; Lim, Lam Kheng; Kheang, Lim Hak; Chun, Chen. 1977. ''Cambodian-Engl ...

in Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

, which has both Hindu and Buddhist reliefs. These are placed in rocky shallows of the river, with water flowing over them. Large numbers of short lingam

A lingam ( sa, लिङ्ग , lit. "sign, symbol or mark"), sometimes referred to as linga or Shiva linga, is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Hindu god Shiva in Shaivism. It is typically the primary '' murti'' or devoti ...

s and deities were intended to purify the water that flowed over them on its way to the city.

Avukana Buddha statue

The Avukana statue is a standing statue of the Buddha near Kekirawa in North Central Sri Lanka. The statue, which has a height of more than , was carved out of a large granite rock face during the 5th century. It depicts a variation of the Abhay ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, 5th century

File:Buddha Bamiyan 1963.jpg, The larger of the Buddhas of Bamiyan

The Buddhas of Bamiyan (or Bamyan) were two 6th-century monumental statues carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley of Hazarajat region in central Afghanistan, northwest of Kabul at an elevation of . Carbon dating of the structural ...

in 1963, before it was destroyed

File:Longmen lu she na.jpg, Part of the Longmen Grottos

File:China - Yungang Grottoes 5 (135940211).jpg, No 5 at the Yungang Grottoes

The Yungang Grottoes (), formerly the Wuzhoushan Grottoes (), are ancient Chinese Buddhist temple grottoes near the city of Datong in the province of Shanxi. They are excellent examples of rock-cut architecture and one of the three most famous anc ...

File:Majishan huge sculptures 20090226.jpg, Detail of the colossal group at the Maijishan Grottoes

The Maijishan Grottoes (), formerly romanized as Maichishan, are a series of 194 caves cut in the side of the hill of Maijishan in Tianshui, Gansu Province, northwest China.

This example of rock cut architecture contains over 7,200 Buddhist s ...

File:Kbal Spean - 018 Vishnu with Lingas near the Bridge (8584753052).jpg, Kbal Spean, Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" withi ...

and lingam

A lingam ( sa, लिङ्ग , lit. "sign, symbol or mark"), sometimes referred to as linga or Shiva linga, is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Hindu god Shiva in Shaivism. It is typically the primary '' murti'' or devoti ...

s

File:Dazu rock carvings baoding 18 layers of hell.JPG, Details of part of the Dazu rock carvings

File:Nihonji daibutsu.jpg, The Nihon-ji daibutsu

or 'giant Buddha' is the Japanese term, often used informally, for large statues of Buddha. The oldest is that at Asuka-dera (609) and the best-known is that at Tōdai-ji in Nara (752). Tōdai-ji's daibutsu is a part of the UNESCO World Herit ...

, 1783

Greek and Roman world

The Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman Athena relief of Sömek

The Athena relief of Sömek is a Greco-Roman rock relief, located some two kilometres north of the village of Sömek in Silifke district of Mersin province in Turkey, near the valley of the Limonlu river, the ancient Lamos. In antiquity, the riv ...

in modern Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, with a warrior nearby, are two of the relatively few examples from the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. Nearby at Adamkayalar there are a series of standing figures in classical niches, probably funerary memorials of the 2nd century AD; similar figures are found at Kanlidivane. All these sites are from former Hittite and Neo-Hittite

The states that are called Syro-Hittite, Neo-Hittite (in older literature), or Luwian-Aramean (in modern scholarly works), were Luwian and Aramean regional polities of the Iron Age, situated in southeastern parts of modern Turkey and northwester ...

territories. The cliff at Behistun, as well as Darius's famous relief, has a Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

reclining Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the ...

of 148 BC with a Greek inscription. Also from the fringes of the Roman world, the famous rock-cut tombs of Petra, Jordan

Petra ( ar, ٱلْبَتْرَاء, Al-Batrāʾ; grc, Πέτρα, "Rock", Nabataean: ), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu or Raqēmō, is an historic and archaeological city in southern Jordan. It is adjacent to the mountain of Jab ...

include figurative elements, mostly now battered by iconoclasm, for example the best-known tomb, known as The Treasury.

Medieval Europe

Standing alone in early medieval Europe is the Madara Rider inBulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, cut around 700 above the palace of a ruler of the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as noma ...

. It shows a rider, about double life-size, spearing a lion, with a dog running behind him. Though the medium of rock relief is without parallels anywhere near, this motif, known as the Thracian horseman, had long been common on stelae in the region, and such motifs appear in metalwork, such as the ewer with a mounted warrior and his prisoner in the enigmatic Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós

The Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós ( hu, Nagyszentmiklósi kincs; german: Schatz von Nagyszentmiklós; ro, Tezaurul de la Sânnicolau Mare) is an important hoard of 23 early medieval gold vessels, in total weighing 9.945 kg (about 22 ...

, and are common in Sasanian silver bowls, which may well have been traded as far as the Balkans.

The (probably) 12th-century Externsteine relief

The Externsteine relief is a monumental rock relief depiction of the Descent from the Cross scene, carved into the side of the Externsteine sandstone formation in the Teutoburg Forest. The Externsteine are located near Detmold, now in the German ...

in southern Germany measures 4.8 m high by 3.7 m wide. It shows the Descent from the Cross

The Descent from the Cross ( el, Ἀποκαθήλωσις, ''Apokathelosis''), or Deposition of Christ, is the scene, as depicted in art, from the Gospels' accounts of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus taking Christ down from the cross after hi ...

of Jesus, a standard scene from Christian art, with a total of ten figures. The circumstances of its making remain unclear, and despite the extensive tradition of medieval reliefs on buildings, making them on natural rock formations at a large size remained very rare.

Americas

Pre-Columbian rock reliefs, mostly using a low relief, include those at

Pre-Columbian rock reliefs, mostly using a low relief, include those at Chalcatzingo

Chalcatzingo is a Mesoamerican archaeological site in the Valley of Morelos (municipality of Jantetelco) dating from the Formative Period of Mesoamerican chronology. The site is well known for its extensive array of Olmec-style monumental art an ...

in Mexico, probably from around 900–700 BC. These reflect Olmec

The Olmecs () were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that ...

style, though the city was controlled by local rulers. They are on vertical cliff faces, and comparable in style and subject matter to stelae and architectural reliefs in the same tradition.

The Inca

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

tradition is very distinctive; they carved rock with mainly horizontal representations of landscapes as one form of huaca

In the Quechuan languages of South America, a huaca or wak'a is an object that represents something revered, typically a monument of some kind. The term ''huaca'' can refer to natural locations, such as immense rocks. Some huacas have been ass ...

; the most famous are the Sayhuite

Sayhuite (Sigh-weetey) is an archaeological site east of the city Abancay, about 3 hours away from the city of Cusco, in the province Abancay in the region Apurímac in Peru. The site is regarded as a center of religious worship for Inca peop ...

Stone and the Quinku rock. These show a landscape, but also many animals; it is not clear if the landscapes represent a real place or are imaginary. These permanent works formed part of a wider Inca tradition of visualizing and modelling landscapes, often accompanied by rituals.

Modern

Modern rock reliefs tend to be colossal, at several times life-size, and are usually memorials of some sort. In America,Mount Rushmore

Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a national memorial centered on a colossal sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore (Lakota: ''Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe'', or Six Grandfathers) in the Black Hills near Keystone, South Dakot ...

is mostly in a very high relief, and the Stone Mountain

Stone Mountain is a quartz monzonite dome Inselberg, monadnock and the site of Stone Mountain Park, east of Atlanta, Georgia. Outside the park is the small city of Stone Mountain, Georgia. The park is the most visited tourist site in the state o ...

relief commemorating three Confederate generals in bas-relief. The rock sculpture of Decebalus

The rock sculpture of Decebalus () is a colossal carving of the face of Decebalus (r. AD 87–106), the last king of Dacia, who fought against the Roman emperors Domitian and Trajan to preserve the independence of his country, which corresponds to ...

in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

is a huge face on an outcrop above the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, begun in 1994. The '' Lion Monument'' or ''Lion of Lucerne'', in Lucerne

Lucerne ( , ; High Alemannic: ''Lozärn'') or Luzern ()Other languages: gsw, Lozärn, label= Lucerne German; it, Lucerna ; rm, Lucerna . is a city in central Switzerland, in the German-speaking portion of the country. Lucerne is the capital o ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, is one of the most artistically successful, designed by Bertel Thorvaldsen

Bertel Thorvaldsen (; 19 November 1770 – 24 March 1844) was a Danish and Icelandic sculptor medalist of international fame, who spent most of his life (1797–1838) in Italy. Thorvaldsen was born in Copenhagen into a working-class Dani ...

and carved in 1820–21 by Lukas Ahorn, as a memorial for the Swiss Guard

The Pontifical Swiss Guard (also Papal Swiss Guard or simply Swiss Guard; la, Pontificia Cohors Helvetica; it, Guardia Svizzera Pontificia; german: Päpstliche Schweizergarde; french: Garde suisse pontificale; rm, Guardia svizra papala)

is ...

s who were massacred in 1792 during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

.''All About Switzerland'' travelguide. Accessed 13 November 2015

Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, Šābuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardas ...

at Naqsh-e Rajabat

File:Detmold Externsteine 1993 5 Relief.jpg, 12th-century Externsteine relief

The Externsteine relief is a monumental rock relief depiction of the Descent from the Cross scene, carved into the side of the Externsteine sandstone formation in the Teutoburg Forest. The Externsteine are located near Detmold, now in the German ...

, Germany, with the Descent from the Cross

The Descent from the Cross ( el, Ἀποκαθήλωσις, ''Apokathelosis''), or Deposition of Christ, is the scene, as depicted in art, from the Gospels' accounts of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus taking Christ down from the cross after hi ...

of Jesus

File:6308 - Luzern - Löwendenkmal.JPG, The '' Lion Monument'' of Lucerne

Lucerne ( , ; High Alemannic: ''Lozärn'') or Luzern ()Other languages: gsw, Lozärn, label= Lucerne German; it, Lucerna ; rm, Lucerna . is a city in central Switzerland, in the German-speaking portion of the country. Lucerne is the capital o ...

File:Frontal view of the Decebalus rock sculpture.jpg, The ''Rock sculpture of Decebalus

The rock sculpture of Decebalus () is a colossal carving of the face of Decebalus (r. AD 87–106), the last king of Dacia, who fought against the Roman emperors Domitian and Trajan to preserve the independence of his country, which corresponds to ...

of the Iron Gates

The Iron Gates ( ro, Porțile de Fier; sr, / or / ; Hungarian: ''Vaskapu-szoros'') is a gorge on the river Danube. It forms part of the boundary between Serbia (to the south) and Romania (north). In the broad sense it encompasses a ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

.

See also

*List of colossal sculpture in situ

A colossal statue is one that is more than twice life-size. This is a list of colossal statues and other sculptures that were created, mostly or all carved, and remain ''in situ''. This list includes two colossal stones that were intended to be m ...

Notes

References

*Bonatz, Dominik, "Religious Representation of Political Power in the Hittite Empire", in ''Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East'', eds, Marlies Heinz, Marian H. Feldman, 2007, Eisenbrauns, , 9781575061351google books

*Canepa, Matthew P., "Topographies of Power, Theorizing the Visual, Spatial and Ritual Contexts of Rock Reliefs in Ancient Iran", in Harmanşah (2014)

google books

*Cotterell, Arthur (ed), ''The Penguin Encyclopedia of Classical Civilizations'', 1993, Penguin, *Downey, S.B., "Art in Iran, iv., Parthian Art", ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', 1986

Online text

*Harle, J.C., ''The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent'', 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, *Harmanşah, Ömür (2014a), "Rock Reliefs are Never Finished", in ''Place, Memory, and Healing: An Archaeology of Anatolian Rock Monuments'', 2014, Routledge, , 9781317575726

google books

*Harmanşah, Ömür (ed) (2014), ''Of Rocks and Water: An Archaeology of Place'', 2014, Oxbow Books, , 9781782976745 *Herrmann, G, and Curtis, V.S., "Sasanian Rock Reliefs", ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', 2002

Online text

*Jessup, Helen Ibbetson, ''Art and Architecture of Cambodia'', 2004, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), *Kreppner, Florian Janoscha, "Public Space in Nature: The Case of Neo-Assyrian Rock-Reliefs", ''Altorientalische Forschungen'', 29/2 (2002): 367–383

online at Academia.edu

*Ledering, Joan

http://www.livius.org *Luschey, Heinz, "Bisotun ii. Archeology", ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'', 2013

Online text

* Rawson, Jessica (ed). ''The British Museum Book of Chinese Art'', 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, * Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L. & Soper A., ''The Art and Architecture of China'', Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675 *Spink, Walter M., ''Ajanta: History and Development Volume 5: Cave by Cave'', 2006, Brill, Leiden,

online

{{Authority control * Types of sculpture

Relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...