Robert Lawson (architect) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Arthur Lawson (1 January 1833 – 3 December 1902) was one of

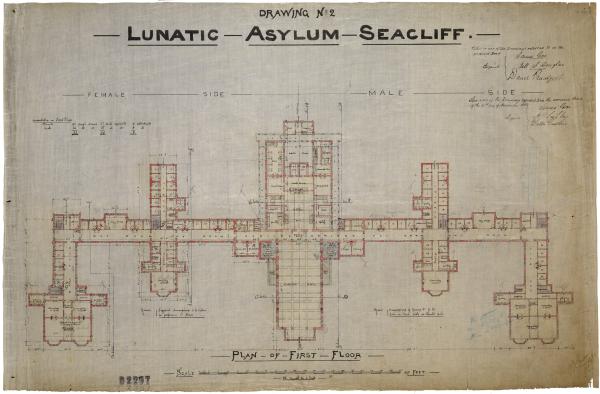

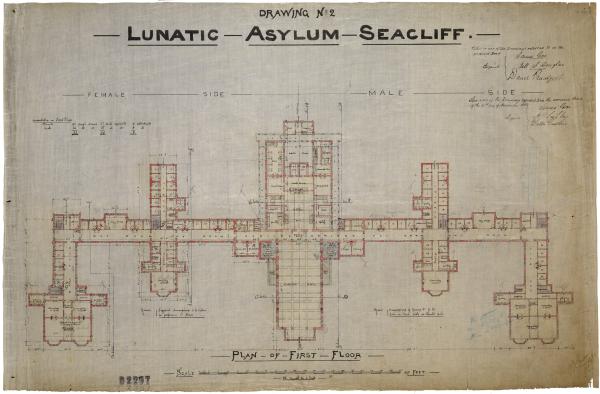

In 1875 the Otago Provincial Council decided to replace the existing Dunedin Lunatic Asylum on the site of what later became the Otago Boys High School with a new one on an existing government reserve at Seacliff 25 km from Dunedin. Once the council was abolished in 1876 responsibility for the complex passed to the Public Works Department, who had a policy that for any building of magnitude a private architect should be employed. Accordingly with regard to Seacliff, William Blair who was Engineer in Charge of the Middle Island (South Island) entered into communication with the Minister for Public Works who authorised him to communicate with Lawson.Prior, pp 54, 56, 65. Blair had been chairman of the building committee for the Knox Church and had been influential in obtaining for Lawson the design of both that building and the later Otago Boys High School.Ledgerwood, pp 185, 187, 195, 215-218, 220. After a meeting between Blair and Lawson, the architect was formally requested by letter to undertake the work, Lawson replied on 17 July 1878 accepting the commission. Lawson’s only previous experience with designing such a building had been that of the Dunedin Benevolent Institution in the 1860s. Lawson decided to design the building in the Scottish Baronial style.

Designed to house 500 patients and 50 staff on its completion the

In 1875 the Otago Provincial Council decided to replace the existing Dunedin Lunatic Asylum on the site of what later became the Otago Boys High School with a new one on an existing government reserve at Seacliff 25 km from Dunedin. Once the council was abolished in 1876 responsibility for the complex passed to the Public Works Department, who had a policy that for any building of magnitude a private architect should be employed. Accordingly with regard to Seacliff, William Blair who was Engineer in Charge of the Middle Island (South Island) entered into communication with the Minister for Public Works who authorised him to communicate with Lawson.Prior, pp 54, 56, 65. Blair had been chairman of the building committee for the Knox Church and had been influential in obtaining for Lawson the design of both that building and the later Otago Boys High School.Ledgerwood, pp 185, 187, 195, 215-218, 220. After a meeting between Blair and Lawson, the architect was formally requested by letter to undertake the work, Lawson replied on 17 July 1878 accepting the commission. Lawson’s only previous experience with designing such a building had been that of the Dunedin Benevolent Institution in the 1860s. Lawson decided to design the building in the Scottish Baronial style.

Designed to house 500 patients and 50 staff on its completion the

In the final period of his life Lawson rarely designed alone. Once in Melbourne, he entered into partnership with the architect

In the final period of his life Lawson rarely designed alone. Once in Melbourne, he entered into partnership with the architect

This architectural ''tour de force'' in the

This architectural ''tour de force'' in the

Lawson designed several large private houses, the best known was at first called "The Camp". Today it is better remembered as

Lawson designed several large private houses, the best known was at first called "The Camp". Today it is better remembered as

Larnach Castle. Retrieved on 2008-02-07. and a further twelve years for the interior to be finished. In 1887 the building was further extended by the addition of a ballroom. In 1880, following the death of his first wife, Larnach had Lawson design in Dunedin's Northern Cemetery a miniaturised version of First Church as a family

Otago Boys High School. Retrieved on 2008-02-08. built of stone with many window

Lawson's classical works tended to be confined to public and corporate buildings. It appears that the Gothic style favoured by the Protestants for their churches was also their preferred choice for their houses. Much of Lawson's classical work is in the town of

Lawson's classical works tended to be confined to public and corporate buildings. It appears that the Gothic style favoured by the Protestants for their churches was also their preferred choice for their houses. Much of Lawson's classical work is in the town of

Forrester Gallery, Oamaru, NZ. Retrieved on 2008-02-07.

This Oamaru

This Oamaru

Robert Lawson was chiefly an architect of his time, designing in the styles then popular. The British emigrants to the colonies wanted architecture to remind them of home, and thus it is not surprising that Lawson's most notable buildings are all in a form of Gothic. Many, such as Larnach Castle and Seacliff Asylum, have been described as Scottish baronial; however, this is not an accurate description, although that particular form of Gothic may have been at times his inspiration. Lawson's particular skill was mixing various forms of similar architecture to create a building that was in its own way unique, rather than a mere pastiche of an earlier style; having achieved this, he then went on to adapt his architecture to accommodate the climate and materials locally available. Local stone and wood were particular favourites of his, especially the good quality limestone of Oamaru, and these were often used in preference to the excellent bricks equally available. Small Gothic

Robert Lawson was chiefly an architect of his time, designing in the styles then popular. The British emigrants to the colonies wanted architecture to remind them of home, and thus it is not surprising that Lawson's most notable buildings are all in a form of Gothic. Many, such as Larnach Castle and Seacliff Asylum, have been described as Scottish baronial; however, this is not an accurate description, although that particular form of Gothic may have been at times his inspiration. Lawson's particular skill was mixing various forms of similar architecture to create a building that was in its own way unique, rather than a mere pastiche of an earlier style; having achieved this, he then went on to adapt his architecture to accommodate the climate and materials locally available. Local stone and wood were particular favourites of his, especially the good quality limestone of Oamaru, and these were often used in preference to the excellent bricks equally available. Small Gothic

Lawson designed an estimated 46 church buildings, 21 banks, 134 houses, 16 school buildings, 13 hotels, 15 civic and institutional buildings, and 120 commercial and industrial buildings. Of these 94 survive, including 46 in Dunedin, 43 in the rest of New Zealand and five in Melbourne.Ledgerwood, pp 237-241.

* 1868: The Star and Garter Hotel, Oamaru.

* 1869: Wesleyan Trinity Church, Dunedin.

*1870: East Taieri Presbyterian church,

Lawson designed an estimated 46 church buildings, 21 banks, 134 houses, 16 school buildings, 13 hotels, 15 civic and institutional buildings, and 120 commercial and industrial buildings. Of these 94 survive, including 46 in Dunedin, 43 in the rest of New Zealand and five in Melbourne.Ledgerwood, pp 237-241.

* 1868: The Star and Garter Hotel, Oamaru.

* 1869: Wesleyan Trinity Church, Dunedin.

*1870: East Taieri Presbyterian church,

Inspired: The Dunedin Architecture of R.A. Lawson

A map and information guide to the architectural highlights of R.A. Lawson in the city of Dunedin.

Lawson: The man behind the name

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lawson, Robert 1833 births 1902 deaths Gothic Revival architects People from Newburgh, Fife Scottish emigrants to colonial Australia Architects from Dunedin Architects of cathedrals New Zealand ecclesiastical architects 19th-century New Zealand architects Burials at Dunedin Northern Cemetery 19th-century Scottish architects Scottish emigrants to New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

's pre-eminent 19th century architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

s. It has been said he did more than any other designer to shape the face of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

architecture of the city of Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

. He is the architect of over forty churches, including Dunedin's First Church for which he is best remembered, but also other buildings, such as Larnach Castle

Larnach Castle (also referred to as "Larnach's Castle") is a mock castle on the ridge of the Otago Peninsula within the limits of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, close to the small settlement of Pukehiki. It is one of a few houses of this ...

, a country house, with which he is also associated.

Born at Newburgh, in Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, he emigrated in 1854 to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

and then in 1862 to New Zealand. He died aged 69 in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of t ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

. Lawson is acclaimed for his work in both the Gothic revival and classical styles of architecture. He was prolific, and while isolated buildings remain in Scotland and Australia, it is in the Dunedin area that most surviving examples can now be found.

Today he is held in high esteem in his adopted country. However, at the time of his death his reputation was at a low ebb following the partial collapse of his Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum (often Seacliff Asylum, later Seacliff Mental Hospital) was a psychiatric hospital in Seacliff, New Zealand. When built in the late 19th century, it was the largest building in the country, noted for its scale and extrava ...

, at the time New Zealand's largest building. In 1900, shortly before his death, he returned to New Zealand from a self-imposed, ten-year exile to re-establish his name, but his sudden demise prevented a full rehabilitation of his reputation. The great plaudits denied him in his lifetime were not to come until nearly a century after his death, when the glories of Victorian architecture began again to be recognised and appreciated.

Early life and education

Lawson was born on 1 January 1833 at 49 Hoggs Place, Abbyhill in the village of Grange of Lindores in the parish of Abdie near Newburgh,Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

.Ledgerwood, pp 1, 3-5. He was the fourth child of Margaret (nee Arthur) and James Lawson, a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters t ...

and sawmiller.

The young Lawson was educated at the Abdie parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

school.

Career

Lawson must have shown an interest in architecture or promise in drawing for he was articled at the age of 15 to architect Andrew Heiton Snr. of Heiton and Heiton inPerth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

(Scotland). After a short time he was transferred to and completed his apprenticeship under James Gillespie Graham

James Gillespie Graham (11 June 1776 – 11 March 1855) was a Scottish architect, prominent in the early 19th century.

Life

Graham was born in Dunblane on 11 June 1776. He was the son of Malcolm Gillespie, a solicitor. He was christened as J ...

who was a leading architect in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. While with Graham he furthered his school education at “Trustees Academy”. Lawson then worked as an assistant architect with John Lessels, where he was credited with the design of a college and two mansions.

Australia

At the age of 21, Lawson armed only with a letter of introduction to one of brother’s friend residing inMelbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

he boarded the ship ''Tongataboo'' on 15 July 1854, arriving in the city on 1 November in that same year.Ledgerwood, pp 7, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 23-25 Like other new arrivals in Australia, he tried many new occupations over the next two years on various goldfields tried gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

mining before eventually settling in the town of Steiglitz where as well as remaining involved in gold mining activities he became the agent for the Melbourne newspaper The Argus and for whom it is believed he also acted as its local correspondent. During this period he occasionally turned his hand to architecture, designing the Free Church

A free church is a Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church does not define government policy, and a free church does not accept church theology or policy definitions fro ...

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

and in 1858 a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

school. He was also involved in assessing and share broking. By 1859 he was secretary of the Steiglitz Prospecting & Mining Company and then its managing director until it was wound up in late 1861. As Lawson came to realise the low probability of success in the gold rush and the precariousness of and by the end of 1861 had moved to Melbourne with the intention of resuming a full-time career in architecture.

In 1861, the first Otago gold rush brought an influx of people to southern New Zealand, including a new generation of emigrants. To service the rapidly expanding population of the region’s principal settlement , the 13 year old town of Dunedin the Descon’s Court of the presbytery of Otago decided now was the time to build a permanent Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

church to serve as its principal place of worship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity. It may involve one or more of activities such as veneration, adoration, praise, and praying. For many, worship is not about an emotion, it is more about a recogni ...

.

In the January 1862 they announced a competition with a prize of £50 to select a suitable design what was to become First Church. Lawson heard about the competition either from his younger brother John Lawson who had already emigrated to Otago or via a copy of the Otago Daily Times that had found their way to Melbourne. He decided to enter the competition and was able to submit from Melbourne a set of drawing under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

of “Presbyter” by the closing date of 15 March 1862. If this pseudonym was designed to catch the eye of the Presbyterian judges, it was well chosen: his design was successful.

Emigration to New Zealand

As a result of winning the commission to design First Church Lawson was able in 1862 to move to Dunedin and open an architectural practice. During the construction of First Church Lawson built up his practice with commissions obtained to design other churches, public buildings, and houses in the vicinity. During the 1870s and 1880s Dunedin rose to be the dominant commercial centre in New Zealand largely due to the wealth generated by gold mining. This was in turn reflected in the number of new buildings being constructed. These commissions ensured that the 1870s in particular were Lawson’s most productive.Ledgerwood, pp 109, 141, 158, 159, 183, 187 This was despite him suffering from ill health which required him to spend two months in Melbourne in 1873 and later in 1874. As he had no partners to share the workload his practice employed a number of young architects, including Thomas Forrester, Percy W. Laing and James-Louis Salmond (from 1888) who later went on to establish their own practices. There are no records to suggest that Lawson entered into any partnerships until a brief relationship with Christchurch architect Thomas Lambert in 1889. In 1876 Lawson was involved in the formation of the Dunedin institute of Civil engineers and Architects, which was intended to counter the competition from employees of the Otago Provincial Council eventually went out of existence by the early 1880s. By the late 1870s following on from the booms bought by the goldfields and then the Vogel Public Works Scheme New Zealand entered a severe economic recession (precipitated by the collapse of the City Bank of Glasgow in 1878) which lasted into the early 1890s and came to be known as the “long depression”. In the winters there was visible hardship and distress and people began to leave in particular to Australia, where Melbourne experienced a boom in the 1880s. Dunedin began to stagnate which caused Lawson’s commissions to change from commercial and industrial clients to predominantly residential. There were however a number of important commissions, among them churches at Gore (1881), Kaihkiki, Riversdale (1881), an office building for Martin and Watson (1882). A prestigious commission was that for the Otago boy’s High School, construction of which commenced in July 1882. His peers were also affected by the lack of work with his Dunedin based rival David Ross as well as Frederick Burrell in Invercargill both departing for Australia.Ledgerwood, foreword by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki.Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

In 1875 the Otago Provincial Council decided to replace the existing Dunedin Lunatic Asylum on the site of what later became the Otago Boys High School with a new one on an existing government reserve at Seacliff 25 km from Dunedin. Once the council was abolished in 1876 responsibility for the complex passed to the Public Works Department, who had a policy that for any building of magnitude a private architect should be employed. Accordingly with regard to Seacliff, William Blair who was Engineer in Charge of the Middle Island (South Island) entered into communication with the Minister for Public Works who authorised him to communicate with Lawson.Prior, pp 54, 56, 65. Blair had been chairman of the building committee for the Knox Church and had been influential in obtaining for Lawson the design of both that building and the later Otago Boys High School.Ledgerwood, pp 185, 187, 195, 215-218, 220. After a meeting between Blair and Lawson, the architect was formally requested by letter to undertake the work, Lawson replied on 17 July 1878 accepting the commission. Lawson’s only previous experience with designing such a building had been that of the Dunedin Benevolent Institution in the 1860s. Lawson decided to design the building in the Scottish Baronial style.

Designed to house 500 patients and 50 staff on its completion the

In 1875 the Otago Provincial Council decided to replace the existing Dunedin Lunatic Asylum on the site of what later became the Otago Boys High School with a new one on an existing government reserve at Seacliff 25 km from Dunedin. Once the council was abolished in 1876 responsibility for the complex passed to the Public Works Department, who had a policy that for any building of magnitude a private architect should be employed. Accordingly with regard to Seacliff, William Blair who was Engineer in Charge of the Middle Island (South Island) entered into communication with the Minister for Public Works who authorised him to communicate with Lawson.Prior, pp 54, 56, 65. Blair had been chairman of the building committee for the Knox Church and had been influential in obtaining for Lawson the design of both that building and the later Otago Boys High School.Ledgerwood, pp 185, 187, 195, 215-218, 220. After a meeting between Blair and Lawson, the architect was formally requested by letter to undertake the work, Lawson replied on 17 July 1878 accepting the commission. Lawson’s only previous experience with designing such a building had been that of the Dunedin Benevolent Institution in the 1860s. Lawson decided to design the building in the Scottish Baronial style.

Designed to house 500 patients and 50 staff on its completion the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

Seacliff Lunatic Asylum (often Seacliff Asylum, later Seacliff Mental Hospital) was a psychiatric hospital in Seacliff, New Zealand. When built in the late 19th century, it was the largest building in the country, noted for its scale and extrava ...

was upon its completion New Zealand's largest building for the next 50 years. Architecturally, this was Lawson at his most exuberant, extravagant and adventurous: Otago Boys High School seems almost severe and restrained in comparison. Turrets on corbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

s project from nearly every corner; the gabled roof line is dominated by a mammoth tower complete with further turrets and a spire. The edifice broadly E shaped ground plan was long by wide. The great tower, actually designed so that the inmates could be observed should they attempt to escape, was almost tall.

It was later said of the design that "the Victorians might not have wanted their lunatics living with them, but they liked to house them grandly".

As well as designing the permanent building Lawson also designed a temporary wooden building to accommodate sixty male patients and staff above the site for the new permanent building. Construction commenced on site in September 1879 and soon became apparent that parts of the site were unstable, first at the site of temporary building, before structural problems within the permanent building began to manifest themselves even before completion in July 1884 at a cost of £78,000. Finally in 1887 a major landslip occurred which rendered the north wing unsafe and it was eventually to be replaced by wooden buildings. The problems with the design could no longer be ignored.

The building continued to deteriorate with the tower demolished in 1945 and the remaining structure in 1957.

In 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February, realising that he may be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction – including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the project’s clerk of works and Lawson himself – were forced to give evidence to support their competence.

The Commissioners apportioned blame to Lawson for constructional defects and not insisting on proper drainage works being carried out, but also placed blame on the Public Works Department for not paying attention to repeated applications from the architect to deal with drainage problems and warnings from Dr James Hector, the Director of Geological Survey.

There later became a popular misconception that the Commission of Inquiry had found Lawson to be "negligent and incompetent" despite these words not appearing in its report. The words are however first known to have appeared in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography.

Before the Seacliff Commission of Inquiry, Lawson had relocated to Wellington on 26 May 1887 to serve as ''locum tenens'' for Wellington architect William Turnbull while he went overseas on a trip from February 1887 to December 1887. The relationship known as Turnbull and Lawson, with Lawson, making periodic visits to Dunedin before permanently returning within 12 months.

Major projects undertaken by Lawson during the late 1880s were the Lawrence Presbyterian Church (1886), Tokomairiro Presbyterian Church (1888) and a grain and woolstore for Reid, Mclean & Co (1889).

Problems at First Church

Despite the problems at Seacliff, from the reports in various newspapers many Dunedin people disagreed with the commission’s finding and Lawson’s reputation among his fellow citizens was intact, though diminished. By 1889 it was apparent that there were issues with dampness on the walls of First Church despite it being only 16 years old. As a result the Deacon’s Court passed over Lawson who was out of flavour with the session and commissioned Christchurch architect Thomas Stoddart Lambert who had an association with Lawson to investigate. Lambert found that the pointing of the stonework was inadequate in places which had allowed water to enter. Also water was able to enter the building due to the poor application of flashings around the pinnacles and gables. The most significant issues was found to be the roof-bearing timbers which had been sealed into the walls without proper ventilation and being of Oregon they had consequently rotted. The resulting four months of repairs by a workforce of between 30 and 40 was completed by July 1890 at a cost of more than £1,200. As both he and his wife were members of the congregation and Lawson an elder of the Presbytery of Otago and Southland these failings of his most prestigious commission must have felt highly embarrassing. When combined with the issues at Seacliff and the economic downturn they were sufficient to cause him to quickly wind up his affairs and depart for Melbourne on 8 May 1890.Final years

In the final period of his life Lawson rarely designed alone. Once in Melbourne, he entered into partnership with the architect

In the final period of his life Lawson rarely designed alone. Once in Melbourne, he entered into partnership with the architect Frederick Grey

Admiral The Hon. Sir Frederick William Grey GCB (23 August 1805 – 2 May 1878) was a Royal Navy officer. As a captain he saw action in the First Opium War and was deployed as principal agent of transports during the Crimean War. He became Fir ...

. Together they designed Earlsbrae Hall, a large Neoclassical house at Essendon Essendon may refer to:

Australia

*Electoral district of Essendon

*Electoral district of Essendon and Flemington

*Essendon, Victoria

**Essendon railway station

**Essendon Airport

*Essendon Football Club in the Australian Football League

United King ...

, Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

. This is now considered by some experts to be one of his greatest works, though it must be attributed to the partnership. It has been thought that perhaps the house was begun before Lawson arrived, but he departed Dunedin on 8 May 1890, and the foundation stone was laid on 16 August 1890, so there was enough time to be appointed and design the mansion. The principal aspect of the design, the tall Corinthian portico, is practically an exact match to those on Lawson's banks in Oamaru, the pediment of the National Bank in particular is essentially repeated here. Often said to resemble a Grecian temple, the architecture of a bold double-height Corinthian columned portico is derived from the Greek Revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but a ...

; the wrapping around the house on three sides, and incorporating a verandah, is also reminiscent of the plantation houses

A plantation house is the main house of a plantation, often a substantial farmhouse, which often serves as a symbol for the plantation as a whole. Plantation houses in the Southern United States and in other areas are known as quite grand and ...

of the American Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

. The cost of construction to the owner Collier McCracken was £35,000; it later sold in 1911 for just £6000. Commercial buildings which survive from Lawson's Melbourne years include the Moran and Cato warehouse in Fitzroy and the College Church in Parkville, which were completed in 1897.

In 1900, at the age of 67, Lawson came out of his ten-year-long self-imposed exile from New Zealand and returned to Dunedin. Here he entered into practice with his former pupil J.Louis Salmond

James Louis Salmond (1868 – 12 March 1950) was a New Zealand architect active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of his buildings remain, particularly in Otago. He established a practice carried on by his son and grandson into the ...

. A number of commercial and residential buildings were erected under their joint names, including the brick house known as "Threave" built for Watson Shennan at 367 High Street. This is one of Lawson's last works. Threave has particularly ornate carved verandahs in the Gothic style, but is today better known for its gardens than architecture. The house and gardens were extensively restored in the 1960s and 1970s by then-owner Geoff Baylis

Geoffrey Thomas Sandford Baylis (24 November 1913 – 31 December 2003) was a New Zealand botanist and Emeritus Professor specialising in plant pathology and mycorrhiza. He was employed at the University of Otago for 34 years undertaking rese ...

.

The Lawson–Salmond partnership would not last long. In 1902 Lawson died suddenly at Pleasant Point, Canterbury, on 3 December. By the time of his death he had begun to re-establish his reputation, having been elected vice-president of the Otago Institute of Architects.

Although much of Lawson's early work has since been either demolished or heavily altered, surviving plans and photographs from the period suggest that the buildings he was working on at this time included a variety of styles. Indeed, Lawson designed principally in both the classical and Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

styles simultaneously throughout his career. His style and manner of architecture can best be explained through an examination of six of his designs, three Gothic and three in the classical style, and each an individual interpretation and use of their common designated style.

Works in the Gothic style

The BritishProtestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

religions were at this period still heavily influenced by the Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglica ...

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of ...

, which had decreed Gothic as the only architectural style suited for Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

worship; Greek, Roman, and Italian renaissance architecture was viewed as "pagan" and inappropriate in the design of churches. Thus Lawson was never given opportunities such as Francis Petre

Francis William Petre (27 August 1847 – 10 December 1918), sometimes known as Frank Petre, was a New Zealand-born architect based in Dunedin. He was an able exponent of the Gothic revival style, one of its best practitioners in New Zea ...

enjoyed when the latter recreated great Italianate renaissance basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its nam ...

s such as the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon Rive ...

. Dunedin had in fact been founded, only thirteen years before Lawson's arrival, by the Free Church of Scotland, a denomination not known for its love of ornament and decoration, and certainly not the architecture of the more Catholic countries.

Lawson's work in Gothic design, like that of most other architects of this period, was clearly influenced by the style and philosophy of Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

. However, he adapted the style for the form of congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

worship employed by the Presbyterian denomination.Mane-Wheoki, Jonathan. (1992). The Architecture of Robert Arthur Lawson. ''Bulletin of New Zealand art history''. Vol 13. The lack of ritual and religious procession

A procession is an organized body of people walking in a formal or ceremonial manner.

History

Processions have in all peoples and at all times been a natural form of public celebration, as forming an orderly and impressive ceremony. Religious ...

s rendered unnecessary a large chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

...

; hence in Lawson's version of the Gothic, the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

...

and transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building with ...

s (the areas which traditionally in Roman and Anglo-Catholic churches contained the Lady Chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British term for a chapel dedicated to "Our Lady", Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church. The chapels are also known as a Mary chapel or a Marian chapel, ...

and other minor chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type ...

s) are merely hinted at in the design. Thus at First Church the tower

A tower is a tall structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting structures.

Towers are specific ...

is above the entrance to the building rather than in its traditional place in the centre of the church at the axis of nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

, chancel and transepts. In all, Lawson designed over forty churches in the Gothic style. Like Benjamin Mountfort's, some were constructed entirely of wood; however, the majority were in stone.

First Church, Dunedin 1873

This architectural ''tour de force'' in the

This architectural ''tour de force'' in the decorated Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

style was designed in 1862. Construction was delayed after the Otago Provincial Council

The Otago Province was a province of New Zealand until the abolition of provincial government in 1876.

The capital of the province was Dunedin. Southland Province split from Otago in 1861, but became part of the province again in 1870.

Area a ...

decided to reduce Bell Hill, on which it was to stand, by some : the hill had proved a major impediment to transport in the rapidly expanding city. As a result the foundation stone wasn't laid until 15 May 1868. Just before the official opening on 23 November 1873 Lawson realized while sailing up the harbour that the spire was too short, and had a slight lean. He insisted on the spire being dismantled and rebuilt to the correct specifications, which was completed in 1875.

The church is dominated by its multi-pinnacle

A pinnacle is an architectural element originally forming the cap or crown of a buttress or small turret, but afterwards used on parapets at the corners of towers and in many other situations. The pinnacle looks like a small spire. It was mainly ...

d tower crowned by a spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires a ...

rising to . The spire is unusual as it is pierced by two-storeyed gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aest ...

d windows on all sides, which give an illusion of even greater height. It can be seen from much of central Dunedin, and dominates the skyline of lower Moray Place.

The expense of the building was not without criticism as some members of the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

synod felt the metropolitan church should not have been so privileged over the country districts where congregants had no purpose designed places of worship or only modest ones. The Reverend Dr Burns's championship of the project ensured it was carried through against such objections.

Externally First Church successfully replicates the effect, if on a smaller scale, of the late Norman cathedrals of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. The cathedral-like design and size can best be appreciated from the rear. There is an apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

flanked by turret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

s, which are dwarfed by the massive gable containing the great rose window

Rose window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in Gothic cathedrals and churches. The windows are divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The term ''rose window' ...

. It is this large circular window which after the spire becomes the focal point of the rear elevations. The whole architectural essay appears here almost European. Inside, instead of the stone vaulted ceiling of a Norman cathedral, there are hammer beams supporting a ceiling of pitched wood and a stone pointed arch

An arch is a vertical curved structure that spans an elevated space and may or may not support the weight above it, or in case of a horizontal arch like an arch dam, the hydrostatic pressure against it.

Arches may be synonymous with vau ...

acts as a simple proscenium

A proscenium ( grc-gre, προσκήνιον, ) is the metaphorical vertical plane of space in a theatre, usually surrounded on the top and sides by a physical proscenium arch (whether or not truly "arched") and on the bottom by the stage floor ...

to the central pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, acces ...

. Above this diffused light enters through a rose window

Rose window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in Gothic cathedrals and churches. The windows are divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The term ''rose window' ...

of stained glass. This is flanked by further lights on the lower level, while twin organ pipes emphasise the symmetry of the pulpit.

The building is constructed of Oamaru stone

Oamaru stone, sometimes called whitestone, is a hard, compact limestone, quarried at Weston, near Oamaru in Otago, New Zealand.

Oamaru stone was used on many of the grand public buildings in the towns and cities of the southern South Island, e ...

, set on foundations of basalt breccia

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of a ...

from Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a town serving as the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast of Dunedin's city centre.

History

Early Māori settlement

The origi ...

, with details carved by Louis Godfrey, who also did much of the woodcarving in the interior. The use of "cathedral glass", coloured but unfigured glass pending the donation of a pictorial window for the rose window is characteristic of Otago's 19th-century churches, where donors were relatively few reflecting the generally "low church" sentiments of the place. Similar examples can be found in Lawson's churches throughout Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

. Notable among these are the former Trinity Methodist Church in Stuart Street, Dunedin (later used as a home for the Fortune Theatre

The Fortune Theatre is a 432-seat West End theatre on Russell Street, near Covent Garden, in the City of Westminster. Since 1989 the theatre has hosted the long running play ''The Woman in Black''.

History

The site was acquired by author, playw ...

), the spired Knox Church in the north of the city, and the Tokomairiro Presbyterian Church in Milton, said at the time of its construction to have been the southernmost building of its height.

Lawson also designed Knox Church, which has a similar tower, also in Dunedin. This building, less well known than First Church, also designed in the 13th-century Gothic style, but in bluestone, is considered by some to be his finest achievement.

Larnach Castle 1871

Lawson designed several large private houses, the best known was at first called "The Camp". Today it is better remembered as

Lawson designed several large private houses, the best known was at first called "The Camp". Today it is better remembered as Larnach Castle

Larnach Castle (also referred to as "Larnach's Castle") is a mock castle on the ridge of the Otago Peninsula within the limits of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, close to the small settlement of Pukehiki. It is one of a few houses of this ...

. It was built in 1871 for William Larnach

William James Mudie Larnach (27 January 1833 – 12 October 1898) was a New Zealand businessman and politician. He is known for his extravagant incomplete house near Dunedin called Larnach's castle by his opponents and now known as Larnach Ca ...

, a local businessman and politician recalled for his ''bravura'' personal style. It has been hailed as one of New Zealand's finest mansions, described on its completion as: "doubtless the most princely, as it is the most substantial and elegant residence in New Zealand". There is a tradition that Larnach designed his house after Castle Forbes, his father's house at Baroona in Australia. The plans, however, are unquestionably from Lawson's office. The origin of the myth is simply that Larnach Castle has verandahs, doubtless insisted on by Larnach, an obviously colonial addition to its otherwise conventional revivalist design. However these do lend it distinction.

Although some have questioned if Larnach Castle was an essay in the revived Scottish baronial manner. The main facade resembles a small, castellated tower house, with the characteristic rubble masonry, turrets and battlements, present at Abbotsford, an exemplar of the style. It has been accurately described as a "castellated villa wrapped in a two-storey verandah". The principal facade is dominated by a central tower complete with a stair turret which gives the house its castle-like appearance.

The interior of the building is ornate, with imported marbles and Venetian glass used in the Italianate decoration. As with First Church, there are also numerous carvings by Louis Godfrey. It took 200 men three years to complete the shellLarnach Castle's Project Site: Welcome to "The Larnach Years" 1871–1898.Larnach Castle. Retrieved on 2008-02-07. and a further twelve years for the interior to be finished. In 1887 the building was further extended by the addition of a ballroom. In 1880, following the death of his first wife, Larnach had Lawson design in Dunedin's Northern Cemetery a miniaturised version of First Church as a family

mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be cons ...

. Larnach was interred in the mausoleum himself. While serving as New Zealand's Minister of Finance and of Mines in 1898, he committed suicide in a committee room of the parliamentary building in Wellington, not because of the financial stresses of the Colonial Bank of New Zealand

The Colonial Bank of New Zealand was a trading bank headquartered in Dunedin, New Zealand which operated independently for more than 20 years. A public company listed on the local stock exchanges it was owned and controlled by New Zealand entrep ...

, as previously thought but because of circulating rumours about an affair between his eldest son and his third wife.

Otago Boys' High School 1885

Otago Boys' High School

, motto_translation = "The ‘right’ learning builds a heart of oak"

, type = State secondary, day and boarding

, established = ; years ago

, streetaddress= 2 Arthur Street

, region = Dunedin

, state = Otago

, zipcod ...

, Arthur Street, Dunedin, was completed in 1885. Often referred to as Gothic, in fact it is a hybrid of several orders of architecture with obvious renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

/Tudor style

Tudor Revival architecture (also known as mock Tudor in the UK) first manifested itself in domestic architecture in the United Kingdom in the latter half of the 19th century. Based on revival of aspects that were perceived as Tudor architecture ...

, and Gothic influences: the nearest style into which it can be categorised is probably Jacobethan

The Jacobethan or Jacobean Revival architectural style is the mixed national Renaissance revival style that was made popular in England from the late 1820s, which derived most of its inspiration and its repertory from the English Renaissance ( ...

(a peculiarly English form of the Neo-Renaissance

Renaissance Revival architecture (sometimes referred to as "Neo-Renaissance") is a group of 19th century architectural revival styles which were neither Greek Revival nor Gothic Revival but which instead drew inspiration from a wide range ...

). The building has long been regarded as one of the finest examples of architecture in Dunedin,Facilities.Otago Boys High School. Retrieved on 2008-02-08. built of stone with many window

embrasure

An embrasure (or crenel or crenelle; sometimes called gunhole in the domain of gunpowder-era architecture) is the opening in a battlement between two raised solid portions (merlons). Alternatively, an embrasure can be a space hollowed out ...

s and corners of lighter quoin

Quoins ( or ) are masonry

Masonry is the building of structures from individual units, which are often laid in and bound together by mortar; the term ''masonry'' can also refer to the units themselves. The common materials of masonry con ...

s. The school's many turrets and towers led to the architect Nathaniel Wales describing it in 1890 as "a semi-ecclesiastical building" in the "Domestic Tudor style of medieval architecture".

The building, though castle-like, is not truly castellated although some of the windows are surmounted by crenelated ornament. Its highest point, the dominating tower, is decorated by stone balustrading. The tower has turrets at each corner – an overall composition more redolent of the early 17th-century English Renaissance than an earlier true castle. While the school's entrance arch was obviously designed to impart an ecclesiastical or collegiate air, the school has the overall appearance of a prosperous Victorian country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peop ...

.

Works in the classical style

Lawson's classical works tended to be confined to public and corporate buildings. It appears that the Gothic style favoured by the Protestants for their churches was also their preferred choice for their houses. Much of Lawson's classical work is in the town of

Lawson's classical works tended to be confined to public and corporate buildings. It appears that the Gothic style favoured by the Protestants for their churches was also their preferred choice for their houses. Much of Lawson's classical work is in the town of Oamaru

Oamaru (; mi, Te Oha-a-Maru) is the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, it is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is south of Timaru and north of Dunedin on the Pacific coast; State Highway 1 and the ra ...

, north of Dunedin. Here, as in Dunedin itself, Lawson built in the local Oamaru stone

Oamaru stone, sometimes called whitestone, is a hard, compact limestone, quarried at Weston, near Oamaru in Otago, New Zealand.

Oamaru stone was used on many of the grand public buildings in the towns and cities of the southern South Island, e ...

, a hard limestone that is ideal for building purposes, especially where ornate moulding is required. The finished stonework has a creamy, sandy colour. Unfortunately, it is not strongly resistant to today's pollution, and can be prone to surface crumbling.

National Bank, Oamaru 1871

This building, completed in 1871, is one of Lawson's successful exercises into classical architecture, designed in a near Palladian style. A perfectly proportionedportico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cul ...

prostyle

Prostyle is an architectural term designating temples (especially Greek and Roman) featuring a row of columns on the front. The term is often used as an adjective when referring to the portico of a classical building, which projects from the ...

, its pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedim ...

supported by four Corinthian columns, projects from a square building of five bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a nar ...

s, the three central bays being behind the portico. The temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

-like portico gives the impression of entering a pantheon rather than a bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

. The proportions of the main facade of this building display a Palladian symmetry, almost worthy of Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of t ...

himself; however, unlike a true Palladian design, the two floors of the bank are of equal value, only differentiated by the windows of the ground floor being round-topped, while those above are the same size but have flat tops. Of all Lawson's classical designs, the National Bank is perhaps the most conventional in terms of adherence to classical rules of architecture as defined in Palladio's I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura

''I quattro libri dell'architettura'' (''The Four Books of Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture by the architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580), written in Italian. It was first published in four volumes in 1570 in Venice, illustrated wi ...

. As his career progressed he became more adventurous in his classical designs, not always with the harmony and success he achieved at the National Bank.

While working on the elegantly simple National Bank, Lawson was also simultaneously employed on the architecturally vastly different Larnach Castle, which suggests that unlike the many notable architects who graduate through their careers from one style to another, Lawson could produce whatever his client required at any stage in his career.

Bank of New South Wales, Oamaru 1883

Built in 1883, located right next to his earlier National Bank, this is also Neoclassical in design, its limestone facade dominated by a great six-columned, unpedimentedportico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cul ...

. The columns in the Corinthian order support a divided entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

; the lower section or architrave

In classical architecture, an architrave (; from it, architrave "chief beam", also called an epistyle; from Greek ἐπίστυλον ''epistylon'' "door frame") is the lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of columns.

The term can a ...

bears the inscription "Bank of New South Wales", while above the frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

remains undecorated. The building, while not jarring, has less architectural merit than the National Bank building, even though it was originally intended to be more classical and impressive than its neighbour. The imposing effect the architect sought is lessened at ground level where the portico's columns are linked by a balustrade. This extinguishes the clean-lined effect one would expect in a classical building of this stature and order and reduces the building's appearance to that of a doll's house. This effect is exacerbated by the windows within the portico (flat topped on the lower floor and round topped on the upper floor); these are disproportionately large and destroy the "temple" effect which the great portico was intended to create. Today, this externally unaltered building is used as an art gallery

An art gallery is a room or a building in which visual art is displayed. In Western cultures from the mid-15th century, a gallery was any long, narrow covered passage along a wall, first used in the sense of a place for art in the 1590s. The lon ...

.The Forrester Gallery.Forrester Gallery, Oamaru, NZ. Retrieved on 2008-02-07.

The Star and Garter Hotel, Oamaru 1867

This Oamaru

This Oamaru Hotel

A hotel is an establishment that provides paid lodging on a short-term basis. Facilities provided inside a hotel room may range from a modest-quality mattress in a small room to large suites with bigger, higher-quality beds, a dresser, a re ...

is one of Lawson's more adventurous forays into classical architecture. Forsaking Palladian-influenced temple-like columns and porticos, he initially took as his inspiration the mannerist

Mannerism, which may also be known as Late Renaissance, is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Ita ...

palazzi, which were a reaction to the more ornate high renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

style of architecture popular in early 16th century Italy. There are even some minor similarities between this building and the Palazzo del Te

or is a palace in the suburbs of Mantua, Italy. It is a fine example of the mannerist style of architecture, and the acknowledged masterpiece of Giulio Romano. Although formed in Italian, the usual name in English of Palazzo del Te is not that ...

. Just as at street level the palazzi often have a ground floor of rusticated stone, so did this hotel. Massive blocks of ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruv ...

were used to create an impression of strength, supporting the more delicately designed floor above; this feeling of strength was further enhanced by double pilasters serving merely to imply a need to support the great weight above.

Above this solid and severe facade that Lawson chose instead of the customary two or three floors, the massive blocks of stone support just one floor. This upper floor is not an obvious piano nobile

The ''piano nobile'' ( Italian for "noble floor" or "noble level", also sometimes referred to by the corresponding French term, ''bel étage'') is the principal floor of a palazzo. This floor contains the main reception and bedrooms of the ho ...

, but appears, though of more delicate and simple design, to be of equal value to the floor below. The rusticated pilasters of the lower floor are continued above, but become smooth dressed stone to match the upper facade. The pilasters' capitals are Corinthian, and as at the Bank of New South Wales they support an undecorated entablature. The centre and focal point of the building is marked by a pediment, which again gives the air of a palazzo.

However, what Lawson created was not a mannerist or indeed Palladian town palazzo at all but a hybrid, while similar, at first glance, to the neo-palladian villas and country houses of the late 18th century found in Italy and England, examples being Villa di Poggio Imperiale and Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

. The Star and Garter, though, through Lawson's "pick, mix and match" approach to different forms of classical architecture is in its own way quite unique.

Since the Star and Garter's completion, many of its windows have either been blocked or enlarged, changes that have been detrimental to the architectural effect Lawson created. The building is now used mainly by a theatre company, although a restaurant at the eastern end of the building retains the hotel's original name.

Appraisal and legacy

Robert Lawson was chiefly an architect of his time, designing in the styles then popular. The British emigrants to the colonies wanted architecture to remind them of home, and thus it is not surprising that Lawson's most notable buildings are all in a form of Gothic. Many, such as Larnach Castle and Seacliff Asylum, have been described as Scottish baronial; however, this is not an accurate description, although that particular form of Gothic may have been at times his inspiration. Lawson's particular skill was mixing various forms of similar architecture to create a building that was in its own way unique, rather than a mere pastiche of an earlier style; having achieved this, he then went on to adapt his architecture to accommodate the climate and materials locally available. Local stone and wood were particular favourites of his, especially the good quality limestone of Oamaru, and these were often used in preference to the excellent bricks equally available. Small Gothic

Robert Lawson was chiefly an architect of his time, designing in the styles then popular. The British emigrants to the colonies wanted architecture to remind them of home, and thus it is not surprising that Lawson's most notable buildings are all in a form of Gothic. Many, such as Larnach Castle and Seacliff Asylum, have been described as Scottish baronial; however, this is not an accurate description, although that particular form of Gothic may have been at times his inspiration. Lawson's particular skill was mixing various forms of similar architecture to create a building that was in its own way unique, rather than a mere pastiche of an earlier style; having achieved this, he then went on to adapt his architecture to accommodate the climate and materials locally available. Local stone and wood were particular favourites of his, especially the good quality limestone of Oamaru, and these were often used in preference to the excellent bricks equally available. Small Gothic Lancet window

A lancet window is a tall, narrow window with a pointed arch at its top. It acquired the "lancet" name from its resemblance to a lance. Instances of this architectural element are typical of Gothic church edifices of the earliest period. Lancet ...

s were often avoided and replaced by large bay windows, allowing the rooms to be flooded with light rather than creating the darker interiors of true Gothic buildings. Larnach Castle has often been criticised as being clumsy and incongruous, but this derives from the persistent misinterpretation of Lawson's work as Scottish baronial. It is true that in a Scottish glen

A glen is a valley, typically one that is long and bounded by gently sloped concave sides, unlike a ravine, which is deep and bounded by steep slopes. Whittow defines it as a "Scottish term for a deep valley in the Highlands" that is "narrower ...

, much of his work would be incongruous, but Lawson realised that he was designing not for the glens and mountains of his homeland, but rather for a new country, with new ideals and vast vistas. Thus, set upon its two-storeyed verandahs, and looking out over the Otago Peninsula

The Otago Peninsula ( mi, Muaūpoko) is a long, hilly indented finger of land that forms the easternmost part of Dunedin, New Zealand. Volcanic in origin, it forms one wall of the eroded valley that now forms Otago Harbour. The peninsula lies sou ...

and Otago Harbour

Otago Harbour is the natural harbour of Dunedin, New Zealand, consisting of a long, much-indented stretch of generally navigable water separating the Otago Peninsula from the mainland. They join at its southwest end, from the harbour mouth. I ...

from above sea level, the mansion seems perfectly positioned.

At the time of Lawson's work the rival schools of Classical and Gothic architecture were both equally fashionable. In his ecclesiastical commissions, Lawson worked exclusively for the Protestant denominations and thus never received the opportunity to build a great church in the classical style. His major works therefore have to be appraised through his use of the Gothic. First Church thus has to be regarded as his masterpiece. His classical works, though often competently and skillfully executed, were mostly confined to smaller public buildings. He never had the opportunity to refine and hone his classical ideas, and therefore these never had the opportunity to make the same impact as his Gothic works.

Much of Lawson's work is either demolished or much altered. Two of his timber Gothic churches survive at Kakanui

The small town of Kakanui lies on the coast of Otago, in New Zealand, fourteen kilometres to the south of Oamaru. The Kakanui River and its estuary divide the township in two. The part of the settlement south of the river, also known as Kakanui ...

(1870) and East Gore (1881). The designs still standing (which include all of the works described in detail above) have ensured that Lawson's reputation has fully recovered from the condemnation he received following the Seacliff enquiry.

Today, Lawson is lauded as the architect of some of New Zealand's finest historic buildings. The Otago Branch of the New Zealand Historic Places Trust has inaugurated a memorial lecture programme, the RA Lawson Lecture, which is presented in Dunedin annually by an eminent local or overseas speaker. NZHPT Otago Branch Archives, Dunedin.

Personal life

Sometime from 1861 onwards Lawson was introduced to Jessie Sinclair Hepburn. Jessie had been born on 1 July 1843 at Kirkcaldy, Fife in Scotland to Rachel and George Hepburn.Ledgerwood, p 235. She had emigrated in 1850 to Otago with her parents and siblings on the ''Poictiers''. They were married on 15 November 1864 at her father's property at Wakari. The service was conducted by the Rev. David M. Stuart, a former pupil at Lawson's Abdie Parish School in Scotland. From 1864 onwards the couple lived in a house on Bellevue Street in Roslyn, Dunedin that Lawson had designed. From Lawson's point of view, this was a good marriage. His father-in-law, George Hepburn, was at the time the second session clerk of First Church, as well as a successful business man and politician with excellent credentials in early Dunedin. Throughout his life Lawson remained a devout Presbyterian, becoming anelder

An elder is someone with a degree of seniority or authority.

Elder or elders may refer to:

Positions Administrative

* Elder (administrative title), a position of authority

Cultural

* North American Indigenous elder, a person who has and ...

and session clerk of First Church like his father-in-law. He was also closely involved in the Sunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

...

movement.

The couple had the following children:

*Rachel Ida (15 March 1866 - 25 July 1956).

*James Newburgh (31 January 1868 - 20 October 1957).

*Margaret Lillian (31 August 1869 - 16 August 1926).

*Jessie Lawson (9 July 1871- 20 August 1878).

Works by Lawson

Lawson designed an estimated 46 church buildings, 21 banks, 134 houses, 16 school buildings, 13 hotels, 15 civic and institutional buildings, and 120 commercial and industrial buildings. Of these 94 survive, including 46 in Dunedin, 43 in the rest of New Zealand and five in Melbourne.Ledgerwood, pp 237-241.

* 1868: The Star and Garter Hotel, Oamaru.

* 1869: Wesleyan Trinity Church, Dunedin.

*1870: East Taieri Presbyterian church,

Lawson designed an estimated 46 church buildings, 21 banks, 134 houses, 16 school buildings, 13 hotels, 15 civic and institutional buildings, and 120 commercial and industrial buildings. Of these 94 survive, including 46 in Dunedin, 43 in the rest of New Zealand and five in Melbourne.Ledgerwood, pp 237-241.

* 1868: The Star and Garter Hotel, Oamaru.

* 1869: Wesleyan Trinity Church, Dunedin.

*1870: East Taieri Presbyterian church, East Taieri

East Taieri is a small township, located between Mosgiel and Allanton in New Zealand's Otago region. It lies on State Highway 1 en route between the city of Dunedin and its airport at Momona. It lies close to the southeastern edge of the Taie ...

.

*1870: St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Dunedin

St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church was a prominent church in Dunedin, New Zealand. Designed by pre-eminent Dunedin Robert Lawson it was constructed in 1870 to serve a rapidly developing area of the city which became notorious for its slum housi ...

.

*1871: Bank of Otago, Oamaru

Oamaru (; mi, Te Oha-a-Maru) is the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, it is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is south of Timaru and north of Dunedin on the Pacific coast; State Highway 1 and the ra ...

. Later occupied by the National Bank.

*1873: First Church of Otago

First Church is a prominent church in the New Zealand city of Dunedin. It is located in the heart of the city on Moray Place, 100 metres to the south of the city centre. The church is the city's primary Presbyterian church. The building is regar ...

, Moray Place, Dunedin.

*1874: Union Bank of Australia (later ANZ Bank), Princes Street

Princes Street ( gd, Sràid nam Prionnsan) is one of the major thoroughfares in central Edinburgh, Scotland and the main shopping street in the capital. It is the southernmost street of Edinburgh's New Town, stretching around 1.2 km (thr ...

, Dunedin.

*1876: Knox Church, Dunedin

Knox Church is a notable building in Dunedin, New Zealand. It houses the city's second Presbyterian congregation and is the city's largest church (in terms of building size, rather than congregation size) of any denomination.

Situated close to t ...

, Dunedin.

*1876: Larnach Castle

Larnach Castle (also referred to as "Larnach's Castle") is a mock castle on the ridge of the Otago Peninsula within the limits of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, close to the small settlement of Pukehiki. It is one of a few houses of this ...

, Otago Oeninsula.

*1880: Dunedin Town Hall

The Dunedin Town Hall, also known as the Dunedin Centre, is a municipal building in the city of Dunedin in New Zealand. It is located in the heart of the city extending from The Octagon, the central plaza, to Moray Place through a whole city blo ...

, Dunedin.

*1881: East Gore Presbyterian Church

East Gore Presbyterian Church is a former Presbyterian church located in Gore, New Zealand. It is located on a bluff overlooking the eastern side of the Mataura River.

Opened in 1881 as the Gore Presbyterian Church it was the town's primary Pr ...

.

*1881: Larnach Mausoleum, Dunedin Northern Cemetery

The Dunedin Northern Cemetery is a major historic cemetery in the southern New Zealand city of Dunedin. It is located on a sloping site close to Lovelock Avenue on a spur of Signal Hill close to the Dunedin Botanic Gardens and the suburb of ...

*1883: Bank of New South Wales, Oamaru (now Forrester Gallery).

*1884: Seacliff Lunatic Asylum