Robert Hues on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Hues (1553 – 24 May 1632) was an English

Robert Hues was born in 1553 at Little Hereford in Herefordshire, England. In 1571, at the age of 18 years, he entered

Robert Hues was born in 1553 at Little Hereford in Herefordshire, England. In 1571, at the age of 18 years, he entered

Hues became interested in

Hues became interested in  ''Tractatus de globis'' begins with a letter by Hues dedicated to Raleigh that recalled geographical discoveries made by Englishmen during Elizabeth I's reign. However, he felt that his countrymen would have surpassed the

''Tractatus de globis'' begins with a letter by Hues dedicated to Raleigh that recalled geographical discoveries made by Englishmen during Elizabeth I's reign. However, he felt that his countrymen would have surpassed the

In later years, Hues lived in

In later years, Hues lived in

8th printing: (in Dutch), quarto.

** 9th printing: (in Latin),

8th printing: (in Dutch), quarto.

** 9th printing: (in Latin),  The following works also are, or appear to be, versions of ''Tractatus de globis et eorum usu'', though they are not mentioned by Markham:

* .

* (in Latin).

* .

* .

* . Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

* , two pts. Collection of the Bodleian Library.

The following works also are, or appear to be, versions of ''Tractatus de globis et eorum usu'', though they are not mentioned by Markham:

* .

* (in Latin).

* .

* .

* . Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

* , two pts. Collection of the Bodleian Library.

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

. He attended St. Mary Hall at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and graduated in 1578. Hues became interested in geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

and mathematics, and studied navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

at a school set up by Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebelli ...

. During a trip to Newfoundland, he made observations which caused him to doubt the accepted published values for variations of the compass. Between 1586 and 1588, Hues travelled with Thomas Cavendish

Sir Thomas Cavendish (1560 – May 1592) was an English explorer and a privateer known as "The Navigator" because he was the first who deliberately tried to emulate Sir Francis Drake and raid the Spanish towns and ships in the Pacific and retu ...

on a circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Mage ...

of the globe, performing astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxi ...

observations and taking the latitudes of places they visited. Beginning in August 1591, Hues and Cavendish again set out on another circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Mage ...

of the globe. During the voyage, Hues made astronomical observations in the South Atlantic, and continued his observations of the variation of the compass at various latitudes

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north–south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pole ...

and at the Equator. Cavendish died on the journey in 1592, and Hues returned to England the following year.

In 1594, Hues published his discoveries in the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

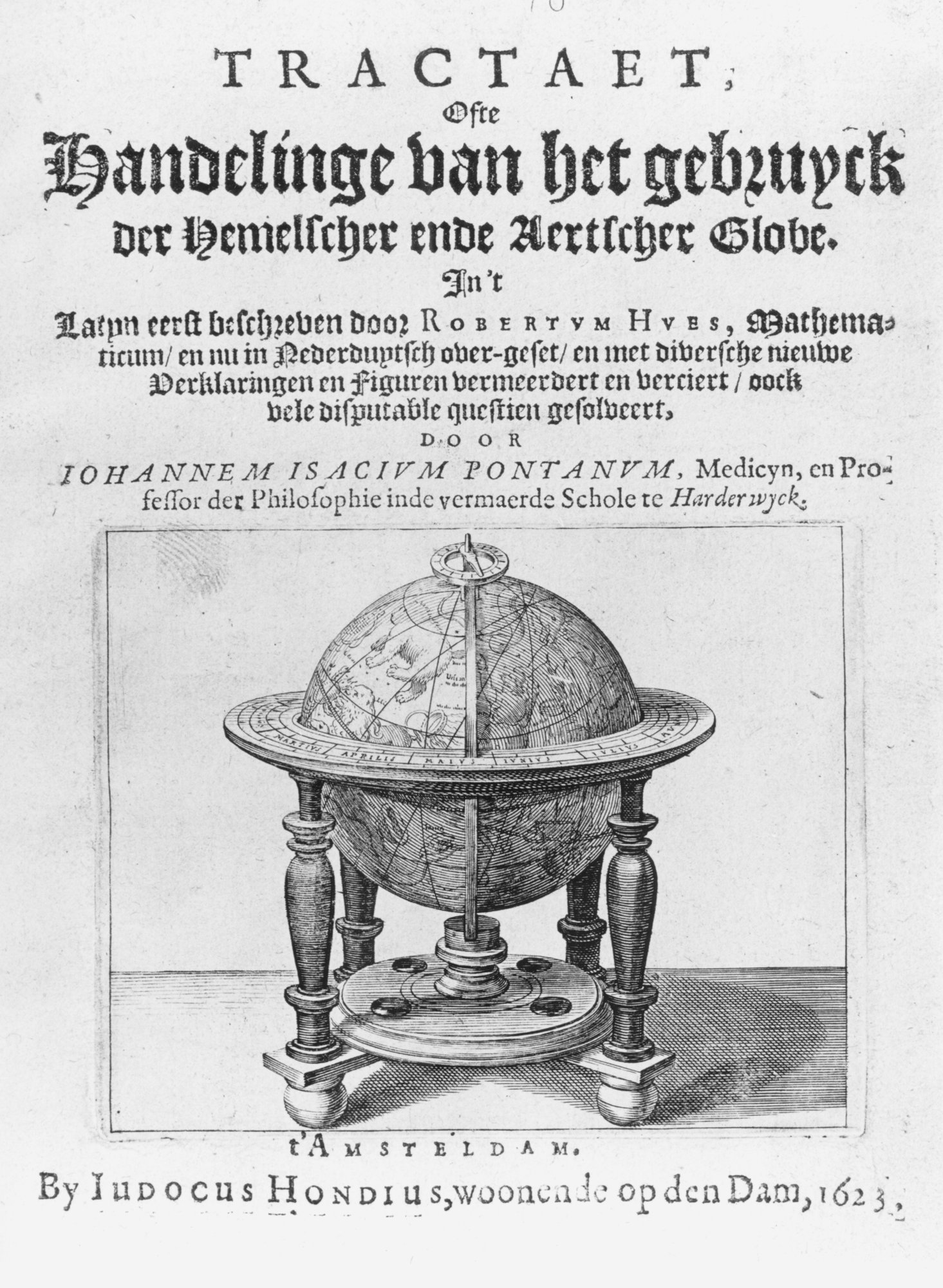

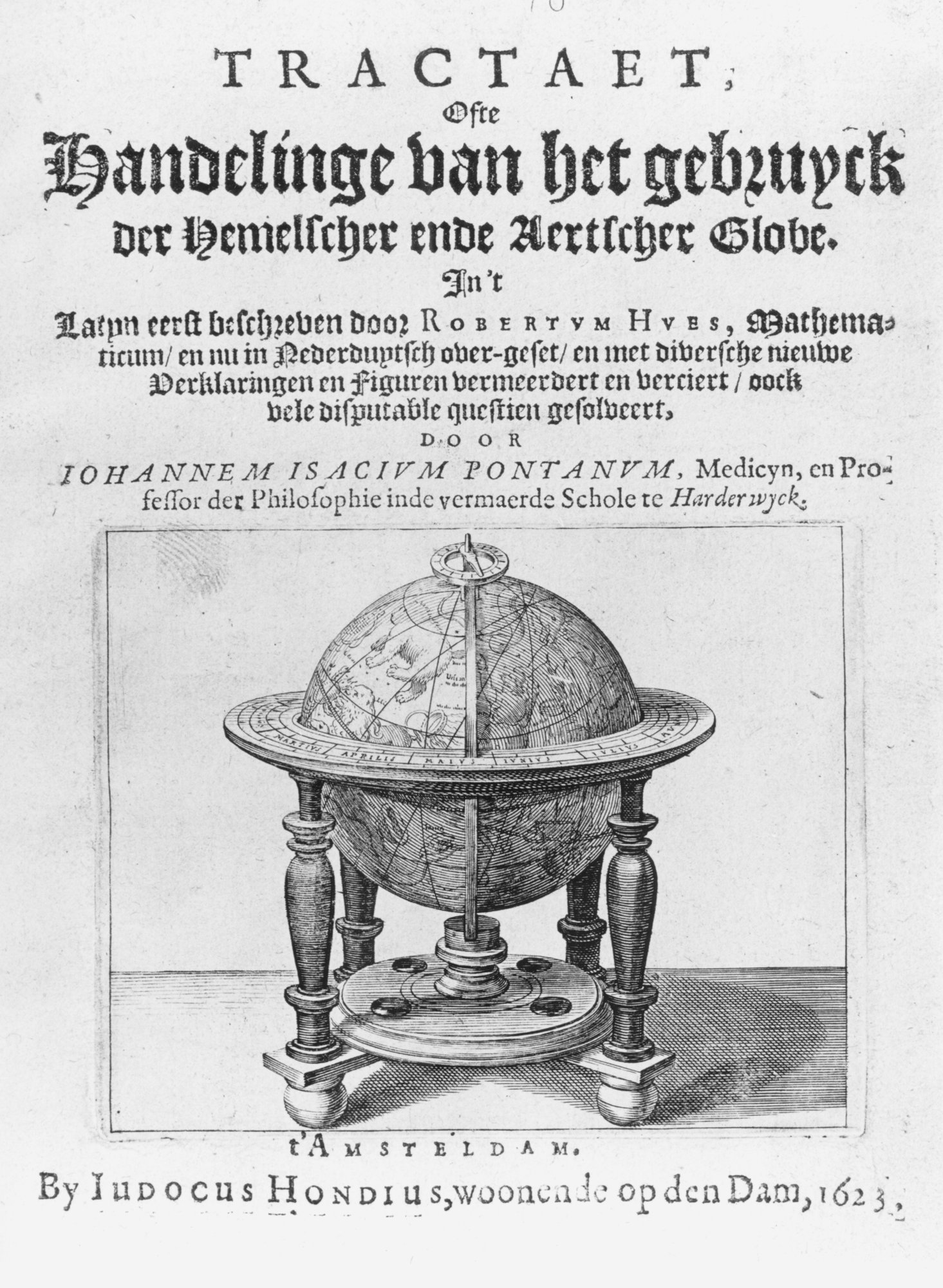

work ''Tractatus de globis et eorum usu'' (''Treatise on Globes and Their Use'') which was written to explain the use of the terrestrial and celestial globes that had been made and published by Emery Molyneux in late 1592 or early 1593, and to encourage English sailors to use practical astronomical navigation. Hues' work subsequently went into at least 12 other printings in Dutch, English, French and Latin.

Hues continued to have dealings with Raleigh in the 1590s, and later became a servant of Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey de Wilton

Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey de Wilton (died 1614) was an English aristocrat, soldier and conspirator. He was convicted of involvement in the Bye Plot against James I of England.

Early life

The son of Arthur Grey, 14th Baron Grey of Wilton, by ...

. While Grey was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

for participating in the Bye Plot, Hues stayed with him. Following Grey's death in 1614, Hues attended upon Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland, when he was confined in the Tower; one source states that Hues, Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot (; – 2 July 1621), also spelled Harriott, Hariot or Heriot, was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator to whom the theory of refraction is attributed. Thomas Harriot was also recognized for his con ...

and Walter Warner

Walter Warner (1563–1643) was an English mathematician and scientist.

Life

He was born in Leicestershire and educated at Merton College, Oxford, graduating B.A. in 1578. Andrew Pyle (editor), ''Dictionary of Seventeenth Century British Phi ...

were Northumberland's constant companions and known as his "Three Magi

Magi (; singular magus ; from Latin '' magus'', cf. fa, مغ ) were priests in Zoroastrianism and the earlier religions of the western Iranians. The earliest known use of the word ''magi'' is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius t ...

", although this is disputed. Hues tutored Northumberland's son Algernon Percy Algernon Percy may refer to:

* Algernon Percy, 10th Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), English military leader

* Algernon Percy, 1st Earl of Beverley (1750–1830), peer known as Lord Algernon Percy from 1766–86

*Hon. Algernon Percy (diplomat ...

(who was to become the 10th Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

) at Oxford, and subsequently (in 1622–1623) Algernon's younger brother Henry. In later years, Hues lived in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

where he was a fellow of the University, and discussed mathematics and related subjects with like-minded friends. He died on 24 May 1632 in the city and was buried in Christ Church Cathedral.

Early years and education

Robert Hues was born in 1553 at Little Hereford in Herefordshire, England. In 1571, at the age of 18 years, he entered

Robert Hues was born in 1553 at Little Hereford in Herefordshire, England. In 1571, at the age of 18 years, he entered Brasenose College

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the m ...

, University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

. English antiquarian Anthony à Wood

Anthony Wood (17 December 1632 – 28 November 1695), who styled himself Anthony à Wood in his later writings, was an English antiquary. He was responsible for a celebrated ''Hist. and Antiq. of the Universitie of Oxon''.

Early life

Anthony W ...

(1632–1695) wrote that when Hues arrived at Oxford he was "only a poor scholar or servitor ... he continued for some time a very sober and serious servant ... but being sensible of the loss of time which he sustained there by constant attendance, he transferred himself to St Mary's Hall". Hues graduated with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree on 12 July 1578, having shown marked skill in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. He later gave advice to the dramatist and poet George Chapman

George Chapman (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, – London, 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been speculated to be the Rival Poet of Shakesp ...

for his 1616 English translation of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, and Chapman referred to him as his "learned and valuable friend". According to the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', there is unsubstantiated evidence that after completing his degree Hues was held in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, though no reason is given for this, then went abroad after his release. It is possible he travelled to Continental Europe.Markham, "Introduction", ''Tractatus de globis'', p. xxxv.

Hues was a friend of the geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

Richard Hakluyt, who was then regent master of Christ Church. In the 1580s, Hakluyt introduced him to Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebelli ...

and explorers

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

and navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

s whom Raleigh knew. In addition, it is likely that Hues came to know astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either ...

and mathematician Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot (; – 2 July 1621), also spelled Harriott, Hariot or Heriot, was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator to whom the theory of refraction is attributed. Thomas Harriot was also recognized for his con ...

and Walter Warner at Thomas Allen's lectures in mathematics. The four men were later associated with Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland, who was known as the "Wizard Earl" for his interest in scientific and alchemical

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

experiments and his library.

Career

Hues became interested in

Hues became interested in geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

and mathematics – an undated source indicates that he disputed accepted values of variations of the compass after making observations off the Newfoundland coast. He either went there on a fishing trip, or may have joined a 1585 voyage to Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

arranged by Raleigh and led by Richard Grenville, which passed Newfoundland on the return journey to England. Hues perhaps become acquainted with the sailor Thomas Cavendish

Sir Thomas Cavendish (1560 – May 1592) was an English explorer and a privateer known as "The Navigator" because he was the first who deliberately tried to emulate Sir Francis Drake and raid the Spanish towns and ships in the Pacific and retu ...

at this time, as both of them were taught by Harriot at Raleigh's school of navigation. An anonymous 17th-century manuscript states that Hues circumnavigated the world with Cavendish between 1586 and 1588 "purposely for taking the true Latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

of places"; he may have been the "NH" who wrote a brief account of the voyage that was published by Hakluyt in his 1589 work ''The Principall Navigations, Voiages, and Discoveries of the English Nation''. In the year that book appeared, Hues was with Edward Wright on the Earl of Cumberland

The title of Earl of Cumberland was created in the Peerage of England in 1525 for the 11th Baron de Clifford.''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press'', 2004. It became extinct in 1643. The dukedom of Cumberland was cr ...

's raiding expedition to the Azores to capture Spanish galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch W ...

s.

Beginning in August 1591, Hues joined Cavendish on another attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Sailing on the ''Leicester'', they were accompanied by the explorer John Davis on the ''Desire''. Cavendish and Davis agreed that they would part company once they had cleared the Strait of Magellan between Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

and Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego

Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego (English: ''Big Island of the Land of Fire'') also formerly ''Isla de Xátiva''Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arc ...

. The expedition was ultimately unsuccessful, although Davis did discover the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

. In the meantime, delayed in small harbours in the Strait with crew members dying from the cold, illness and starvation, Cavendish turned back eastwards to return to England. He was plagued by mutinous crewmen, and also by natives and Portuguese who attacked his sailors seeking food and water on shore. Increasingly depressed, Cavendish died in 1592 somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, possibly a suicide.

During the voyage, Hues made astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxi ...

observations of the Southern Cross

Crux () is a constellation of the southern sky that is centred on four bright stars in a cross-shaped asterism commonly known as the Southern Cross. It lies on the southern end of the Milky Way's visible band. The name ''Crux'' is Latin for ...

and other stars of the Southern Hemisphere while in the South Atlantic, and also observed the variation of the compass there and at the Equator. He returned to England with Davis in 1593,Markham, "Introduction", ''Tractatus de globis'', p. xxxvi. and published his discoveries in the work ''Tractatus de globis et eorum usu'' (''Treatise on Globes and Their Use'', 1594), which he dedicated to Raleigh. The book was written to explain the use of the terrestrial and celestial globes that had been made and published by Emery Molyneux in late 1592 or early 1593. Apparently, the book was also intended to encourage English sailors to use practical astronomical navigation, although Lesley Cormack has observed that the fact it was written in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

suggests that it was aimed at scholarly readers on the Continent. In 1595, William Sanderson, a London merchant who had largely financed the globes' construction, presented a small globe together with Hues' "Latin booke that teacheth the use of my great globes" to Robert Cecil, a statesman who was spymaster

A spymaster is the person that leads a spy ring, or a secret service (such as an intelligence agency).

Historical spymasters

See also

*List of American spies

*List of British spies

* List of German spies

*List of fictional spymasters

This ...

and minister to Elizabeth I and James I. Hues' work subsequently went into at least 12 other printings in Dutch (1597, 1613 and 1622), English (1638 and 1659), French (1618) and Latin (1611, 1613, 1617, 1627, 1659 and 1663). In his book ''An Accidence or The Path-way to Experience: Necessary for all Young Sea-men'' (1626), John Smith, who founded the first permanent English settlement in North America at Jamestown, Virginia, listed Hues' book among the works that a young seaman should study.

''Tractatus de globis'' begins with a letter by Hues dedicated to Raleigh that recalled geographical discoveries made by Englishmen during Elizabeth I's reign. However, he felt that his countrymen would have surpassed the

''Tractatus de globis'' begins with a letter by Hues dedicated to Raleigh that recalled geographical discoveries made by Englishmen during Elizabeth I's reign. However, he felt that his countrymen would have surpassed the Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both in ...

and Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

if they had a complete knowledge of astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

and geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ...

, which were essential to successful navigation. In the preface of the book, Hues rehearsed arguments that proved the earth is a sphere, and refuted opposing theories. The treatise was divided into five parts. The first part described elements common to Molyneux's terrestrial and celestial globes, including the circles and lines inscribed on them, zones and climates, and the use of each globe's wooden horizon circle and brass meridian. The second part described planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s, fixed stars and constellations; while the third part described the lands and seas shown on the terrestrial globe, and discussed the length of the circumference of the earth and of a degree of a great circle.Markham, "Introduction", ''Tractatus de globis'', p. xlii. Part 4, which Hues considered the most important part of the work, explained how the globes enabled seamen to determine the sun's position, latitude, course and distance, amplitudes and azimuth

An azimuth (; from ar, اَلسُّمُوت, as-sumūt, the directions) is an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. More specifically, it is the horizontal angle from a cardinal direction, most commonly north.

Mathematical ...

s, and time and declination. The final part of the work contained a treatise inspired by Harriot on rhumb lines. In the work, Hues also published for the first time the six fundamental navigational propositions involved in solving what was later termed the "nautical triangle" used for plane sailing. Difference of latitude and departure (or longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lette ...

) are two sides of the triangle forming a right angle, the distance travelled is the hypotenuse

In geometry, a hypotenuse is the longest side of a right-angled triangle, the side opposite the right angle. The length of the hypotenuse can be found using the Pythagorean theorem, which states that the square of the length of the hypotenuse e ...

, and the angle between difference of latitude and distance is the course. If any two elements are known, the other two can be determined by plotting or calculation using tables of sines

Sines () is a city and a municipality in Portugal. The municipality, divided into two parishes, has around 14,214 inhabitants (2021) in an area of . Sines holds an important oil refinery and several petrochemical industries. It is also a popular ...

, tangents

In geometry, the tangent line (or simply tangent) to a plane curve at a given point is the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. Leibniz defined it as the line through a pair of infinitely close points on the curve. More ...

and secants.

In the 1590s, Hues continued to have dealings with Raleigh – he was one of the executors of Raleigh's will – and he may have been the "Hewes" who dined with Northumberland regularly in 1591. He later became a servant of Thomas Grey, the 15th and last Baron Grey de Wilton

Baron Grey de Wilton is a title that has been created twice, once in the Peerage of England (1295) and once in the Peerage of Great Britain (1784). The first creation was forfeit and the second creation is extinct.

History First creation

The fi ...

(1575–1614). For participating in the Bye Plot, a conspiracy by Roman Catholic priest William Watson William, Willie, Bill or Billy Watson may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Watson (songwriter) (1794–1840), English concert hall singer and songwriter

* William Watson (poet) (1858–1935), English poet

* Billy Watson (actor) (1923–2022), A ...

to kidnap James I and force him to repeal anti-Catholic legislation, Grey was attainted and forfeited his title in 1603. The following year, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Grey was given consent for Hues to stay in the Tower with him. Between 1605 and 1621, Northumberland was also confined in the Tower; he was suspected of involvement in the Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who sough ...

of 1605 because his relative Thomas Percy was among the conspirators.

In 1616, following Grey's death, Hues began to be "attendant upon th'aforesaid Earle of Northumberland for matters of learning", and was paid a yearly sum of £40 to support his research until Northumberland's death in 1632. Wood stated that Harriot, Hues and Warner were Northumberland's "constant companions, and were usually called the Earl of Northumberland's Three Magi. They had a table at the Earl's charge, and the Earl himself did constantly converse with them, and with Sir Walter Raleigh, then in the Tower". Together with the scientist Nathanael Toporley and the mathematician Thomas Allen, the men kept abreast of developments in astronomy, mathematics, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

and the physical sciences

Physical science is a branch of natural science that studies non-living systems, in contrast to life science. It in turn has many branches, each referred to as a "physical science", together called the "physical sciences".

Definition

Phy ...

, and made important contributions in these areas.Kargon, "The Wizard Earl and the New Science" in ''Atomism in England'', pp. 5–17 at 16. According to the letter writer John Chamberlain, Northumberland refused a pardon offered to him in 1617, preferring to remain with Harriot, Hues and Warner. However, the fact that these companions of Northumberland were his "Three Magi" studying with him in the Tower of London has been regarded as a romanticisation by the antiquarian John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

and disputed for lack of evidence. Hues was tutor to Northumberland's sons: first Algernon Percy Algernon Percy may refer to:

* Algernon Percy, 10th Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), English military leader

* Algernon Percy, 1st Earl of Beverley (1750–1830), peer known as Lord Algernon Percy from 1766–86

*Hon. Algernon Percy (diplomat ...

, who subsequently became the 10th Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

, at Oxford where he matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

at Christ Church in 1617; and later Algernon's younger brother Henry in 1622–1623. Hues lived at Christ Church at this time, but may have occasionally attended upon Northumberland at Petworth House

Petworth House in the parish of Petworth, West Sussex, England, is a late 17th-century Grade I listed country house, rebuilt in 1688 by Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, and altered in the 1870s to the design of the architect Anthony Sa ...

in Petworth, West Sussex, and at Syon House in London after the latter's release from the Tower in 1622. Hues sometimes met Walter Warner in London, and they are known to have discussed the reflection of bodies.

Later life

In later years, Hues lived in

In later years, Hues lived in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

where he discussed mathematics and allied subjects with like-minded friends. Cormack states he was a fellow at the University. Under the terms of the will of Thomas Harriot, who died on 2 July 1621, Hues and Warner were given the responsibility of helping Harriot's executor Nathaniel Torporley to prepare Harriot's mathematical papers for publication. Hues was also required to help price Harriot's books and other possessions for sale to the Bodleian Library.

Hues, who did not marry, died on 24 May 1632 in Stone House, St. Aldate's (opposite the Blue Boar in central Oxford). This was the house of John Smith, M.A.

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

, the son of a cook at Christ Church named J. Smith. In his will, Hues made many small bequest

A bequest is property given by will. Historically, the term ''bequest'' was used for personal property given by will and ''deviser'' for real property. Today, the two words are used interchangeably.

The word ''bequeath'' is a verb form for the act ...

s to his friends, including a sum of £20 to his "kinswoman" Mary Holly (of whom nothing is known), and 20 nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteri ...

to each of her three sisters. He was buried in Christ Church Cathedral, and a monumental brass to him was placed in Christ Church with the following inscription:

Works

* (inLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

), octavo

Octavo, a Latin word meaning "in eighth" or "for the eighth time", (abbreviated 8vo, 8º, or In-8) is a technical term describing the format of a book, which refers to the size of leaves produced from folding a full sheet of paper on which multip ...

. The following reprints are referred to by Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president for ...

in his introduction to the Hakluyt Society

The Hakluyt Society is a text publication society, founded in 1846 and based in London, England, which publishes scholarly editions of Primary source, primary records of historic voyages, travels and other geographical material. In addition to it ...

's 1889 reprint of the English version of ''Tractatus de globis'' at pp. xxxviii–xl:

** 2nd printing: (in Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

), quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

.

** 3rd printing: (in Latin), octavo. A reprint of the first edition of 1594.

** 4th printing: (in Dutch), quarto.

** 5th printing: (in Latin). Contains the Index Geographicus. DeGolyer Collection in the History of Science and Technology (now History of Science Collections), University of Oklahoma

, mottoeng = "For the benefit of the Citizen and the State"

, type = Public research university

, established =

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.7billion (2021)

, pr ...

.

** 6th printing: (in Latin), quarto.

** 7th printing: (in French), octavo.

**  8th printing: (in Dutch), quarto.

** 9th printing: (in Latin),

8th printing: (in Dutch), quarto.

** 9th printing: (in Latin), duodecimo

Paper size standards govern the size of sheets of paper used as writing paper, stationery, cards, and for some printed documents.

The ISO 216 standard, which includes the commonly used A4 size, is the international standard for paper size. I ...

.

** 10th printing: .

** 11th printing: A Latin version by Jodocus Hondius and John Isaac Pontanus appeared in London in 1659. Octavo.

** 12th printing: , octavo. Collection of Yale University Library

The Yale University Library is the library system of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Originating in 1701 with the gift of several dozen books to a new "Collegiate School," the library's collection now contains approximately 14.9 mill ...

.

** 13th printing: (in Latin).

:The Hakluyt Society's reprint of the English version was itself published as:

:*.

The following works also are, or appear to be, versions of ''Tractatus de globis et eorum usu'', though they are not mentioned by Markham:

* .

* (in Latin).

* .

* .

* . Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

* , two pts. Collection of the Bodleian Library.

The following works also are, or appear to be, versions of ''Tractatus de globis et eorum usu'', though they are not mentioned by Markham:

* .

* (in Latin).

* .

* .

* . Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

* , two pts. Collection of the Bodleian Library.

Notes

References

* , chs. 2–4. * Markham, Clements R., "Introduction", in . * . * .Further reading

;Articles *. ;Books *. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hues, Robert 1553 births 1632 deaths 16th-century English mathematicians 17th-century English mathematicians Academics of the University of Oxford Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford Alumni of St Mary Hall, Oxford Burials at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford English geographers People from Herefordshire