Robert Howe (Continental Army officer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Howe (; c. 1732 – December 14, 1786) was a

Howe was born in 1732 to Job Howe (also spelled "Howes"), the grandson of colonial Governor James Moore, who presided over the southern portion of the

Howe was born in 1732 to Job Howe (also spelled "Howes"), the grandson of colonial Governor James Moore, who presided over the southern portion of the

After allegations circulated in South Carolina about Howe's dalliances with a woman, the Continental Congress finally removed him from command of the Southern Department on September 25, 1778, replacing him with Major General

After allegations circulated in South Carolina about Howe's dalliances with a woman, the Continental Congress finally removed him from command of the Southern Department on September 25, 1778, replacing him with Major General

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

general from the Province of North Carolina

Province of North Carolina was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712(p. 80) to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monarch of Great Britain was repre ...

during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The descendant of a prominent family in North Carolina, Howe was one of five generals, and the only major general, in the Continental Army from that state. He also played a role in the colonial and state governments of North Carolina, serving in the legislative bodies of both.

Howe served in the colonial militia during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

and commanded Fort Johnston at the mouth of the Cape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a long blackwater river in east central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River (North Carol ...

. He also served as a colonel of Royal Governor William Tryon

Lieutenant-General William Tryon (8 June 172927 January 1788) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who served as governor of North Carolina from 1764 to 1771 and the governor of New York from 1771 to 1777. He also served durin ...

's artillery during the War of the Regulation

The Regulator Movement, also known as the Regulator Insurrection, War of Regulation, and War of the Regulation, was an uprising in Provincial North Carolina from 1766 to 1771 in which citizens took up arms against colonial officials, whom they v ...

. Howe suffered greatly when Tryon, a personal friend, became Governor of New York, and he staunchly opposed Tryon's successor. He became active in organizing efforts within North Carolina and among the American colonies between 1773 and 1775 and was an active member of the North Carolina Provincial Congress

The North Carolina Provincial Congresses were extra-legal unicameral legislative bodies formed in 1774 through 1776 by the people of the Province of North Carolina, independent of the British colonial government. There were five congresses. They ...

. At the outset of the Revolutionary War, Howe was promoted to brigadier general and was heavily involved in actions in the Southern Department, commanding the Continental Army and Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

militia forces in defeat in the First Battle of Savannah.

Howe's career as a military commander was contentious and consumed primarily by conflict with political and military leaders in Georgia and South Carolina. In 1778, he fought a duel with Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina which was spurred in part by Howe's conflict with South Carolina's state government. Political and personal confrontations, combined with Howe's reputation as a womanizer among those who disfavored him, eventually led to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

stripping him of his command over the Southern Department. He was then sent to New York, where he served under General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

in the Hudson Highlands

The Hudson Highlands are mountains on both sides of the Hudson River in New York state lying primarily in Putnam County on its east bank and Orange County on its west. They continue somewhat to the south in Westchester County and Rockland Count ...

, although Howe did not have a successful or significant career in that theater. He sat as a senior officer on the court-martial board that sentenced to death John André, a British officer accused of assisting Benedict Arnold in the latter's plot to change allegiance and deliver West Point to the British. Howe himself was accused of attempting to defect to the British, but the accusations were cast aside at the time as having been based in a British attempt to cause further discord in the Continental Army. Howe also played a role in putting down several late-war mutinies by members of the Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

Lines in New Jersey and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and returned home to North Carolina in 1783. He again became active in state politics, but died in December 1786 while en route to a session of the North Carolina House of Commons

The North Carolina House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the North Carolina General Assembly. The House is a 120-member body led by a Speaker of the House, who holds powers similar to those of the President pro-tem in the North Ca ...

.

Early life and family

Howe was born in 1732 to Job Howe (also spelled "Howes"), the grandson of colonial Governor James Moore, who presided over the southern portion of the

Howe was born in 1732 to Job Howe (also spelled "Howes"), the grandson of colonial Governor James Moore, who presided over the southern portion of the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

. Job was also a descendant of Governor John Yeamans

Sir John Yeamans, 1st Baronet (bapt. 28 February 1611 – 1674) was an English colonial administrator and planter who served as Governor of Carolina from 1672 to 1674. Contemporary descriptions of Yeamans described him as "a pirate ashore."

...

. Howe's mother may have been Job's first wife Martha, who was the daughter of colonial North Carolina jurist Frederick Jones., cf , where Jane, Job's third wife, is attributed as his mother, and , where Howe's mother is called Sarah. Job Howe's ancestors had been planters and political figures in South Carolina during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Prior to Howe's birth, his family left Charleston to settle on the banks of the Cape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a long blackwater river in east central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River (North Carol ...

in the Province of North Carolina

Province of North Carolina was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712(p. 80) to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monarch of Great Britain was repre ...

. Howe's father was a member of the extended Moore family, formerly of South Carolina, who settled the lower Cape Fear River and collectively owned more than of farmland on it by the 1730s. Job Howe died in 1748, leaving his estate and the wealth of his parents to Robert. Robert had two brothers and two sisters, all of whom were mentioned in Job's will.

As a young boy, Howe may have been sent to England to obtain an education, although several sources doubt that Howe made the journey. At some point between 1751 and 1754, after completing his education, Howe married Sarah Grange, who was heiress to a large fortune. Howe had numerous affairs, fathering an unknown number of children in and out of wedlock, including a son, Robert; two daughters, Mary and Ann; and up to four additional daughters whose mothers' names are not recorded. Howe was widely considered a womanizer by contemporaries; by 1772 he became estranged from Grange, and the two separated. In the year of their formal separation, Howe recorded a deed for the support of his wife.

Loyalist sympathizer and diarist Janet Schaw described Howe prior to the revolution:

Howe inherited a large amount of assets from his grandmother and, upon the death of his father, became the owner of "Howe's Point" a plantation on the Cape Fear River, as well as a rice plantation near what was formerly known as Barren Inlet (now called Mason Inlet). The site of the former plantation is located on the mainland directly across from Figure Eight Island

Figure Eight Island is a barrier island in the U.S. state of North Carolina, just north of Wrightsville Beach, widely known as an affluent summer colony and vacation destination. The island is part of the Wilmington Metropolitan Area, and lies ...

. Howe also owned a plantation called "Mount Misery" in what was Bladen County

Bladen County ()

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

. His grandmother had provided Howe with slaves and money with which Howe was intended to build his fortune.

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

Colonial political and military service

Around 1755, Howe captained a militia company in Bladen County, and was appointed a justice of the peace for that county in 1756. Howe was elected to theProvince of North Carolina

Province of North Carolina was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712(p. 80) to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monarch of Great Britain was repre ...

House of Burgesses from Bladen County in 1760 and served until 1762. In 1764, the Assembly created Brunswick County, and Howe was both appointed its justice of the peace and re-elected to the Assembly from the new county. Howe would be re-elected six more times from Brunswick County. In 1765, Howe worked with other colonial leaders such as Hugh Waddell, Abner Nash

Abner Nash (August 8, 1740December 2, 1786) was the second Governor of the U.S. state of North Carolina between 1781 and 1782, and represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress from 1782 to 1786.

Life story

Nash was born the son of Co ...

, and Cornelius Harnett

Cornelius Harnett (April 10, 1723 – April 28, 1781) was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Wilmington, North Carolina. He was a leading American Revolutionary statesman in the Cape Fear region, and a delegate for North ...

to found the Wilmington Sons of Liberty organization, which was active in protesting the Stamp Act 1765 that taxed most printed materials. At the time, the members of the Sons of Liberty did not consider their resistance to be rebellion, as it was based on the idea that government officials who performed acts in opposition to the will of the people were not acting with full authority. After the resolution of the Stamp Act Crisis, Howe was made an officer of the provincial exchequer. Despite the Cape Fear River area being the epicenter of Stamp Act protests in North Carolina, Howe took no substantial part in the active confrontations with Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

William Tryon

Lieutenant-General William Tryon (8 June 172927 January 1788) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who served as governor of North Carolina from 1764 to 1771 and the governor of New York from 1771 to 1777. He also served durin ...

, due in large part to their personal friendship and the patronage provided by the Governor for Howe's political ambitions.

During the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, Howe served alongside provincial soldiers from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. In 1766, he was commissioned as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of militia and was given command of Fort Johnston, located at the entrance of the Cape Fear River in present-day Southport, North Carolina. Howe served in this capacity between 1766 and 1767, and again between 1769 and 1773. Although satisfied with this position, Howe ultimately desired to obtain a commission in the regular British Army, which was traditionally a prerequisite for the commander of Fort Johnston. Howe was never granted this commission, despite Tryon's support. In the 1768 session of the colonial assembly, Howe played a prominent role by introducing a bill to remedy a currency shortage in the colony. His bill would have led to the acceptance of commodities as legal tender in the province, but it was not passed. The Regulator movement was in part based on the grievances farmers in the North Carolina backcountry had about back taxes and pressure from private creditors, both of which Howe's 1768 bill had attempted to address.

Despite his efforts to reform the province's policies, Howe was made a colonel of artillery by Governor Tryon and served under the Governor against armed protesters in the piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

during the War of the Regulation

The Regulator Movement, also known as the Regulator Insurrection, War of Regulation, and War of the Regulation, was an uprising in Provincial North Carolina from 1766 to 1771 in which citizens took up arms against colonial officials, whom they v ...

. Howe was among the Governor's entourage when he confronted the Regulators in Hillsborough in 1768, and in 1771, at the Battle of Alamance

The Battle of Alamance, which took place on May 16, 1771, was the final battle of the Regulator Movement, a rebellion in colonial North Carolina over issues of taxation and local control, considered by some to be the opening salvo of the Ameri ...

, Howe served in a dual role as a commander of artillery and quartermaster general. In early 1773, when Josiah Quincy II

Josiah Quincy II (; February 23, 1744April 26, 1775) was an American lawyer and patriot. He was a principal spokesman for the Sons of Liberty in Boston prior to the Revolution and was John Adams' co-counsel during the trials of Captain Thomas ...

visited North Carolina to foster cooperation between Southern activists and those in Boston, he investigated the causes of the War of the Regulation to which he had been sympathetic. Howe served as Quincy's guide and with the assistance of Cornelius Harnett and William Hooper

William Hooper (June 28, 1742 October 14, 1790) was an American Founding Father, lawyer, and politician. As a member of the Continental Congress representing North Carolina, Hooper signed the Continental Association and the Declaration of ...

convinced Quincy that the Regulator movement had been unjustified and wrong to take up arms against Tryon. Quincy found Howe to be a "most happy compound of the man of sense, the sword, the Senate, and the buck ... a favorite of the man of sense and the female world", continuing to say that " owehas faults and vice – but alas who is without them." More importantly, however, Quincy's visit with Howe, Hooper, and Harnett engendered a desire among those present to open up inter-colonial lines of communication in order to coordinate responses to future impositions by the British government.

Howe's private fortunes were never stable, and between 1766 and 1775, he was forced to mortgage land and sell slaves to generate funds. In 1770, Howe was able to purchase Kendal Plantation on the Cape Fear River, a rice plantation, but in 1775, he mortgaged it for around £214. While the causes of Howe's financial misfortunes are unknown, several contemporary critics held that the cause was Howe's need to keep up appearances among the ruling elite, while Josiah Martin, Tryon's successor as Royal Governor, believed Howe's misfortunes were evidence of his potential for malfeasance with the public money. In particular, Martin believed that Howe was intentionally under-staffing Fort Johnston in order to pocket excess funds the colonial assembly had appropriated for the garrison there, which was a common form of embezzlement among previous commanders and other royal officials. Howe, as a legislator and public official, had a poor working relationship with Martin, and Martin deprived him of his appointed offices – the captaincy of Fort Johnston and his position with the provincial exchequer – shortly after the new governor's arrival. A legislative confrontation in 1770 over the Provincial Assembly's attempts to pass a law authorizing attachment of real property in North Carolina owned by persons living in England placed Howe in direct confrontation with Martin, who preferred a requirement that colonial subjects seek relief from courts in England rather than in North Carolina. Martin believed that Howe's virulent opposition to the new governor's policies was driven by Howe's anger at being deprived of his valuable appointed positions.

Revolutionary political and militia service

In December 1773, the North Carolina colonial assembly created acommittee of correspondence

The committees of correspondence were, prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independe ...

, to which Howe, as well as Richard Caswell

Richard Caswell (August 3, 1729November 10, 1789) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the List of Governors of North Carolina, first and fifth Governor of North Carolina, governor of the U.S. state, state of North Carolina from 1 ...

, John Harvey John Harvey may refer to:

People Academics

* John Harvey (astrologer) (1564–1592), English astrologer and physician

* John Harvey (architectural historian) (1911–1997), British architectural historian, who wrote on English Gothic architecture ...

, John Ashe, Joseph Hewes

Joseph Hewes (July 9, 1730– November 10, 1779) was an American Founding Father, a signer of the Continental Association and U.S. Declaration of Independence, and a native of Princeton, New Jersey, where he was born in 1730. Hewes's parents were ...

, and Samuel Johnston

Samuel Johnston (December 15, 1733 – August 17, 1816) was an American planter, lawyer, and statesman from Chowan County, North Carolina, Chowan County, North Carolina. He represented North Carolina in both the Continental Congress and the Un ...

were appointed. That committee was tasked with corresponding with other colonies to coordinate plans of resistance to British attempts to tax or otherwise burden the colonists. Beginning in 1774, Howe was a member of the Wilmington and Brunswick County Committees of Safety, and in August of that year, served as a member of a committee that organized the collection of corn, flour, and pork to be sent to Boston. At the time, the Port of Boston

The Port of Boston ( AMS Seaport Code: 0401, UN/LOCODE: US BOS) is a major seaport located in Boston Harbor and adjacent to the City of Boston. It is the largest port in Massachusetts and one of the principal ports on the East Coast of the Unite ...

had been closed by one of the Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measur ...

, specifically the Boston Port Act, which was in reaction to the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

and other protests against the Tea Act

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help th ...

.

When the First Provincial Congress convened on August 25, 1774, Howe served as a member of that body representing Brunswick County. The First Provincial Congress quickly passed a bill banning the exportation of all pitch, tobacco, tar, and other trade goods to England and banned the importation of British tea into North Carolina. Also in 1774, Howe penned several documents expressing what would become known as Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

or "whig" sympathies, including an address demanding reforms from Royal Governor Josiah Martin. On April 7, 1775, Howe delivered an address to the colonial assembly formally rebuffing Governor Martin's demands that the extra-legal Second Provincial Congress be dissolved. Howe's response as adopted by the assembly led to Martin proroguing the colonial legislative body. In 1775, when Howe received news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War, he began to drill the local militia, using the unusual combination of drums and fiddles as opposed to the standard fifes and drums.

On July 15, 1775, Howe led 500 militiamen from Brunswick Town on a raid on the governor's mansion with the intent of kidnapping Governor Martin. The plot failed when Martin made an early-morning escape from Fort Johnston, fleeing to on July 19. Howe ordered the militia to put the fort's structures to the torch, starting with the home of its commanding officer and Howe's successor, Captain John Collet, who had previously been accused of corruption by the Committee of Safety. After fleeing, Martin made a proclamation on August 8, 1775, that attributed the growing unrest in North Carolina to what he termed "'the basest and most scandalous Seditious and inflammatory falsehoods'" propagated by the Committee of Safety in Wilmington.

Howe once again represented Brunswick County in the Third Provincial Congress in Hillsborough beginning on August 20, 1775, and was appointed to the committee charged with developing a test oath for members of the legislative body. The oath declared allegiance to the King of England but denied the power of Parliament to tax to American colonies. During the Fourth North Carolina Provincial Congress

The Fourth North Carolina Provincial Congress was one of five extra-legal unicameral bodies that met beginning in the summer of 1774 through 1776. They were modeled after the colonial lower house (House of Commons). These congresses created a go ...

in 1776, Howe was noted to have proclaimed that "'Independence seems to be the word. I know not one of the dissenting voice.'"

Continental Army service

Burning of Norfolk

On September 1, 1775, the Third North Carolina Provincial Congress appointed Howe to lead the newly createdSecond North Carolina Regiment

The 2nd North Carolina Regiment was an American infantry unit that was raised for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. In 1776 the regiment helped defend Charleston, South Carolina. Ordered to join George Washington's ma ...

of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

as its colonel. Initially, Howe headquartered his command in New Bern

New Bern, formerly called Newbern, is a city in Craven County, North Carolina, United States. As of the 2010 census it had a population of 29,524, which had risen to an estimated 29,994 as of 2019. It is the county seat of Craven County and t ...

during the fall of 1775 and was charged by the Provincial Congress with protecting the northern half of North Carolina up to the border with Virginia. At the time, British forces under the command of John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the last Royal Governor of the Colony of Virginia, were ravaging the tidewater region

Tidewater refers to the north Atlantic coastal plain region of the United States of America.

Definition

Culturally, the Tidewater region usually includes the low-lying plains of southeast Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, southern Mary ...

of Virginia. Howe, of his own initiative, brought his North Carolina troops into Virginia, arriving shortly after the Battle of Great Bridge

The Battle of Great Bridge was fought December 9, 1775, in the area of Great Bridge, Virginia, early in the American Revolutionary War. The victory by colonial Virginia militia forces led to the departure of Royal Governor Lord Dunmore and any r ...

. Howe then directed the occupation of Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, which had recently been abandoned by Loyalist forces, and assumed command of the various North Carolina and Virginia units there. The region around Norfolk was being occupied by Loyalist militia units under Dunmore's command.

Howe, as senior officer chosen over the more junior William Woodford

William Woodford (October 6, 1734 – November 13, 1780) was a Virginia planter and militia officer who distinguished himself in the French and Indian War, and later became general of the 2nd Virginia Regiment in the American Revolutionary War, ...

of Virginia, engaged in contentious negotiations over access to supplies with the captains of British ships anchored off Norfolk, which were by that time overcrowded with Loyalist refugees. The situation deteriorated, and Norfolk was burned on January 1, 1776, in an action started by British marines and a bombardment by Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

vessels and completed by Patriot forces. The fire raged on for two more days, and Howe ordered most of the buildings that remained standing to be razed before he withdrew, to further render the location useless to the British. During Howe's time in command at Norfolk, Woodford described the North Carolinian as a "brave, prudent & spirited commander". On December 22, 1775, Howe was formally thanked by the Virginia Convention, and on April 27, 1776, he received the same honor from the Fourth North Carolina Provincial Congress.

Charleston, 1776–1777

In March 1776, Howe was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General by the Second Continental Congress along with fellow North Carolinian James Moore. Howe and Moore were two of five North Carolinians to be given a general's commission in the Continental Army. Initially, Howe was given command of all Continental forces in Virginia, but soon both he and Moore were ordered to South Carolina. Howe arrived first, as the presence of theBritish Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

and Royal Navy under the command of General Henry Clinton at the mouth of the Cape Fear River delayed Moore's descent. When Clinton arrived off the coast of North Carolina, he issued a proclamation offering a pardon to anyone who had taken up arms against the crown with the explicit exception of Howe and fellow revolutionary Cornelius Harnett, then serving as president of the North Carolina Provincial Council, the executive body in the revolutionary state. Howe's plantation, Kendal, was sacked by the British during their maneuvers around Wilmington.

Upon arriving in Charleston, Howe acted as an adjutant to Major General Charles Lee, who had been appointed Commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army. Howe directly commanded the South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

militia during the First Siege of Charleston in June 1776 and was assigned command over the defenses of the city proper. Lee was recalled to the North to assist General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, and in his absence, James Moore was appointed Commander of the Southern Department. Howe was left in command of Charleston and Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

in Lee's absence, and in September 1776, he became embroiled in a controversy involving the provincial assembly of South Carolina allowing its officers to recruit soldiers from North Carolina's continental line units. Howe pleaded with the Provincial Congress of North Carolina to allow South Carolina to recruit within the former state's borders because of the greater number of white males in that state. Eventually, North Carolina acceded to that request but only after ordering Howe to reclaim the North Carolinians who had already been lured away by the South Carolinians. The South Carolina Council took offense and demanded that Howe pay the recruitment bonuses for the men if he wished to have them back. With James Moore's death on April 15, 1777, Howe assumed command of the Southern Department.

Florida and political conflict 1777–1778

Howe's style of command was quick to cause discontent, and on August 20, 1777, the South Carolina Assembly protested against Howe's right to command soldiers within the borders of South Carolina. He was nonetheless promoted to the rank ofmajor general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

on October 20, 1777, the only North Carolinian to reach that rank in the Continental Army. Howe often deferred to the civil leadership of the various states that made up his command, often referring conflicts with state officials to the Continental Congress to resolve. Of particular note was an early conflict with Georgia's state government, which insisted that the governor of that state retain command of the state's militia during military engagements. When asked for an official opinion, Congress sided with Howe, who believed that command of the militia should be relinquished to him during such engagements. Complicating matters, however, was the fact that Congressional funding for military expenditures was given over to the states rather than the army officers, forcing Howe to rely on state governments for funding.

In 1778, he was ordered to act on a plan developed by General Charles Lee to assault British West Florida

British West Florida was a colony of the Kingdom of Great Britain from 1763 until 1783, when it was ceded to Spain as part of the Peace of Paris.

British West Florida comprised parts of the modern U.S. states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alab ...

– a plan that Howe disfavored. A previous expedition in 1777, in which Howe did not directly participate, had ended quickly in failure. Congress overrode Howe's concerns about the expedition and directed him to proceed in conjunction with Georgia's militia into Florida. The combined Army's progress into Florida was made slow by a lack of provisions and particularly by a lack of slaves who Howe requested be made available to build roads and perform pioneering functions for the march southward.

On June 29, 1778, Howe captured Fort Tonyn on the St. Marys River, which forms a portion of the border between Georgia and Florida. Georgia Governor John Houstoun

John Houstoun ( ; August 31, 1744 – July 20, 1796) was an American lawyer and statesman from Savannah, Georgia. He was one of the original Sons of Liberty and also a delegate for Georgia in the Second Continental Congress in 1775. He was the ...

refused to give up command of his militia to the Continental Army general and declined to participate in Howe's council. To make matters worse, when South Carolina militia units arrived in Georgia under the command of Colonel Andrew Williamson, their commander also refused to allow Howe to command that state's militia units. Shortly after this minor incursion, the British received reinforcements and pressed toward Savannah. By July 14, 1778, Howe was forced to pull his units back north and returned to Charleston. The general received much of the blame for the expedition's failure, as Georgia officials were quick to cast aspersions on the Continental command, which was compounded by Congress' failure to understand Howe's inability to control the Georgia militia despite their prior determination of his command authority over militia units.

Duel with Christopher Gadsden, 1778

Howe's squabbles with local political and militia leaders were not his sole difficulties. On August 30, 1778, Howe engaged in apistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, an ...

duel with Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina over an offense Gadsden perceived stemming from his resignation in 1777 while under Howe's command. This controversy, like many in which Howe was involved, centered on the conflict between the Continental Army and state governments' desires to retain local control over their officers and soldiers. Gadsden responded to the perceived offense by drafting and circulating a letter attacking Howe's intelligence and ability as a commander and questioning Howe's legal authority to issue orders to South Carolina Continentals. Howe took offense and demanded satisfaction from Gadsden on August 17, 1778.

During the duel, Colonel Charles Pinckney Charles Pinckney (March 7, 1732 - September 22, 1782), also known as Colonel Charles Pinckney, was a prominent South Carolina lawyer and planter based in Charleston, South Carolina. Commissioned as a colonel for the Charles Towne Militia in the colo ...

, father of South Carolina Governor Charles Pinckney Charles Pinckney may refer to:

* Charles Pinckney (South Carolina chief justice) (died 1758), father of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

* Colonel Charles Pinckney (1731–1782), South Carolina politician, loyal to British during Revolutionary War, fa ...

, served as Howe's second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

, while Colonel Barnard Elliot served as second to Gadsden. Howe, shooting first, missed his shot at eight paces, although the ball grazed Gadsden's ear. Gadsden then intentionally fired above his own left shoulder and demanded Howe fire again, a demand Howe refused. At the conclusion of the duel, the participants made amends and parted ways. The affair did not end privately, as the ''South Carolinian and American Gazette'' published a full story covering the duel on September 3, 1778, and in the same month, the ill-fated Major John André, the British officer who would later serve as a facilitator for Benedict Arnold's change of allegiance, published an 18-stanza satirical poem about the duel set to the tune of Yankee Doodle

"Yankee Doodle" is a traditional song and nursery rhyme, the early versions of which predate the Seven Years' War and American Revolution. It is often sung patriotically in the United States today. It is the state anthem of Connecticut. Its ...

.

Removal from command and the Battle of Savannah, 1778

After allegations circulated in South Carolina about Howe's dalliances with a woman, the Continental Congress finally removed him from command of the Southern Department on September 25, 1778, replacing him with Major General

After allegations circulated in South Carolina about Howe's dalliances with a woman, the Continental Congress finally removed him from command of the Southern Department on September 25, 1778, replacing him with Major General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

. Howe remained with the Southern army and commanded it from Savannah. While awaiting Lincoln's arrival in Savannah with reinforcements, Howe set up defenses around that city, preparing for an imminent attack. Governor Houstoun sparred again with Howe, refusing to grant him more than meager militia support.

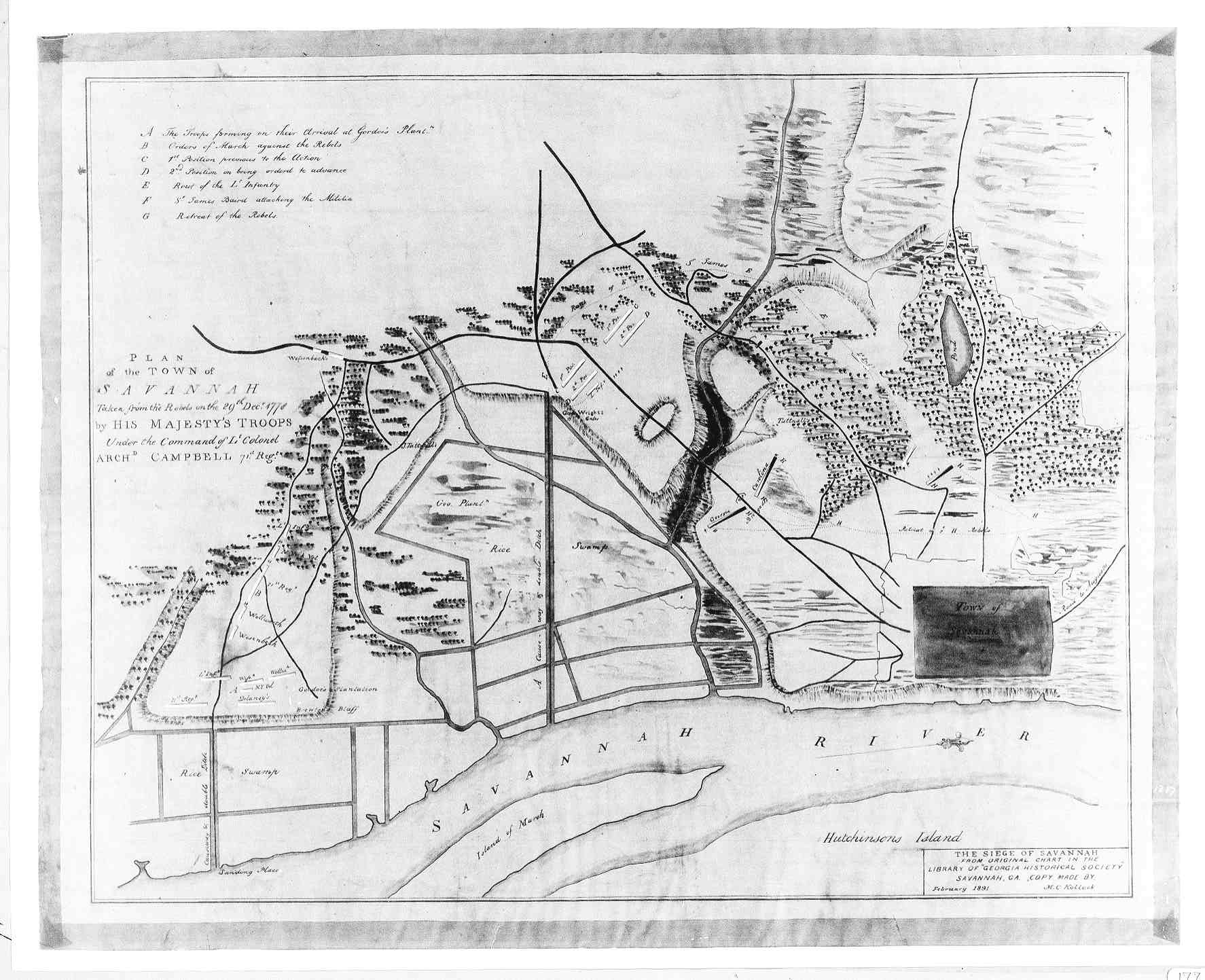

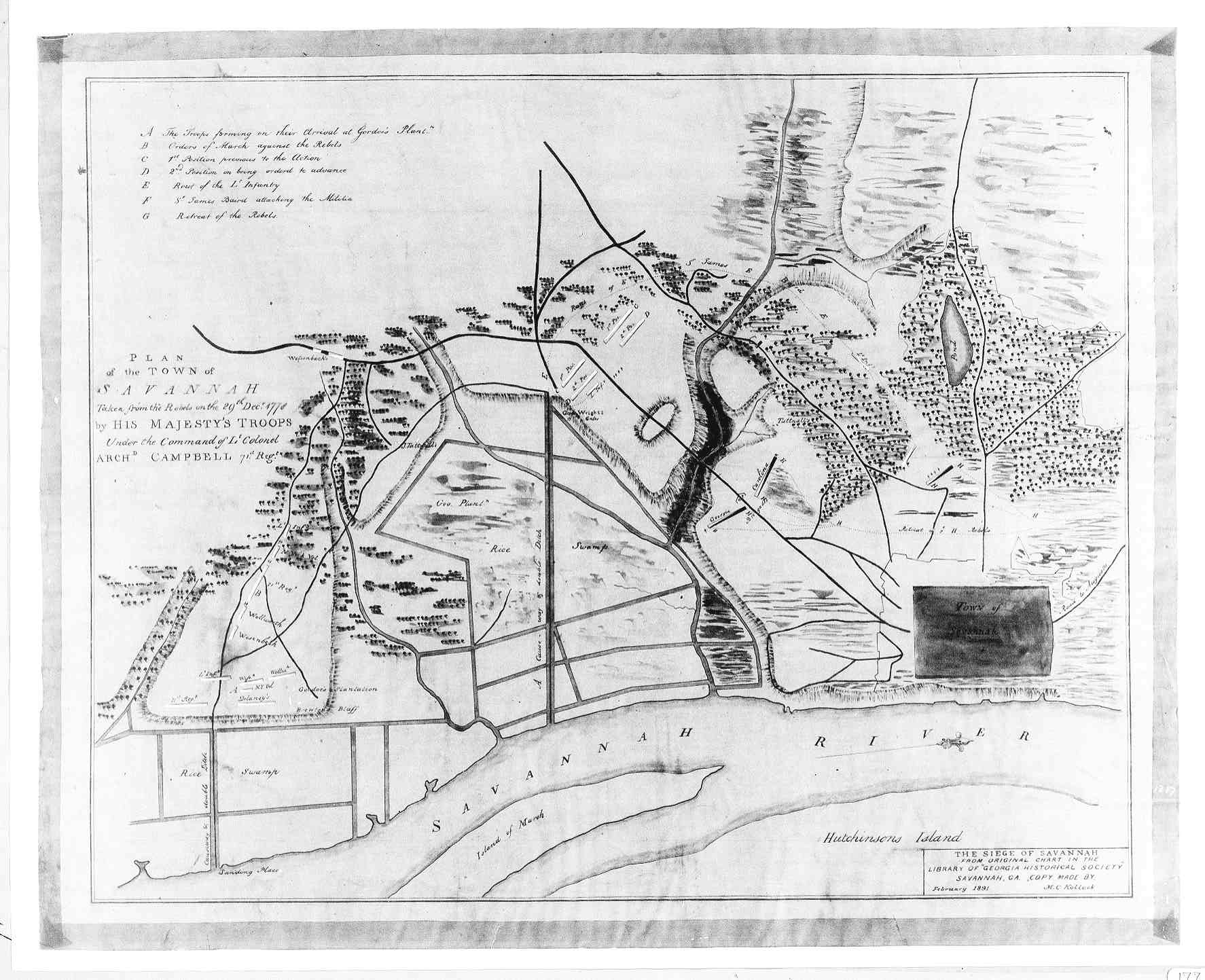

During the First Battle of Savannah on December 29, 1778, the British landed near the city, and under the command of Archibald Campbell Archibald Campbell may refer to:

Peerage

* Archibald Campbell of Lochawe (died before 1394), Scottish peer

* Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll (died 1513), Lord Chancellor of Scotland

* Archibald Campbell, 4th Earl of Argyll (c. 1507–1558) ...

, managed to flank Howe's army, which was drawn up in the open for battle, by taking a path through a marshy area Howe believed was impassable. Howe had previously ordered a scout to look for any paths through the swamp, but Campbell's route, which was shown to the British commander by a slave, remained unknown to the Patriots. Howe's position was otherwise strong and defensible, but the appearance of the British in the Patriot rear caused a panic. The militia under Howe's command fled instantly, and more than 500 Patriots and Continental Army soldiers were killed or captured. The ensuing defeat gave Savannah to the British, for which Howe received much blame. On January 3, 1779, Howe formally relinquished his command to Lincoln.

Howe's failure at Savannah led to criticism from Georgia state officials, who believed he had abandoned the state to the British, as well as from fellow Continental Army generals, such as William Moultrie

William Moultrie (; November 23, 1730 – September 27, 1805) was an American planter and politician who became a general in the American Revolutionary War. As colonel leading a state militia, in 1776 he prevented the British from taking Charle ...

, who criticized Howe for even attempting to resist the British while being so greatly outnumbered. During his testimony before a later court–martial, Howe claimed that he knew about the pathway through the swamp taken by the British, but stated that he did not defend it because he believed the chance of an attack along the path was "so remote". This contradicted earlier testimony from Georgia militia officer George Walton

George Walton (c. 1749 – February 2, 1804), a Founding Father of the United States, signed the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Georgia and also served as the second chief executive of Georgia.

Early life

Wal ...

, who stated that Howe did not know about the path prior to the battle and that Howe told Walton that he was mistaken in believing a path through the swamps existed.

Hudson Valley and Connecticut, 1779

After Lincoln's arrival, Howe was ordered to join the Continental Army in the North, which he rejoined on May 19, 1779. Suffering from injuries caused by a fall, Howe was unable to undertake any duties for a month after his arrival. Initially, Howe was charged with defendingConnecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

from British raids, such as those conducted by his former mentor, William Tryon, and Tryon's adjutant, Edmund Fanning

Edmund Fanning (July 16, 1769 – April 23, 1841) was an American explorer and sea captain, known as the "Pathfinder of the Pacific."

Life

Born in Stonington in the British Crown Colony of Connecticut to Gilbert and Huldah Fanning, from ne ...

. Howe's headquarters were in Ridgefield, Connecticut

Ridgefield is a town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. Situated in the foothills of the Berkshire Mountains, the 300-year-old community had a population of 25,033 at the 2020 census. The town center, which was formerly a borough ...

.

On June 18, 1779, shortly after the Battle of Stony Point, Howe was ordered to assist General Israel Putnam

Israel Putnam (January 7, 1718 – May 29, 1790), popularly known as "Old Put", was an American military officer and landowner who fought with distinction at the Battle of Bunker Hill during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). He als ...

in assaulting a British fortification at Verplanck's Point, which sat across the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

from Stony Point. Howe was charged with commanding the artillery barrage and infantry assault of that position, but was given too few field pieces, entrenching tools, provisions, and little ammunition to make a serious attempt at taking the fortification. He advised Washington that an assault would be unfeasible and called off the siege with Washington's consent. Historians have noted that Howe's inability to take the British fortifications damaged his career and that he was never again given a major command. Contemporaries such as General William Irvine criticized Howe as "having a ''talent'' ... of finding many supposed obstructions, and barely plausible pretences for his delay" in assaulting Verplanck's Point.

After Stony Point, Howe was assigned first to the command of the left wing of Washington's army composed of Massachusetts brigades under Generals John Nixon and John Glover, with his command again in Ridgefield, Connecticut. While military action was infrequent in Howe's region of control, he was integral in the recruitment and cultivation of a substantial spy network which provided the Patriots with information about British positions on Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

and along the Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is a marine sound and tidal estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It lies predominantly between the U.S. state of Connecticut to the north and Long Island in New York to the south. From west to east, the sound stretches from the Eas ...

.

West Point and Benedict Arnold conspiracy, 1779–1780

As part of his command duties, Howe was chosen by Washington as president of the court–martial convened to determine the propriety of General Benedict Arnold's conduct while serving as the commandant of Philadelphia in 1778 and 1779. During that time, Arnold was alleged to have conducted business with British merchants and to have undertaken private business transactions that were inappropriate given his position, among other improprieties. The tribunal, which met at Howe's headquarters in Middletown, Connecticut, adjourned for several months due to a threatened British attack but reconvened in December 1779 and closed in January 1780. During the interlude in the fall of 1779, Howe was ordered by Washington to move into position to attack the British in conjunction with an expected combined French naval and land-based assault, although the French assault in New York never materialized. The court-martial rendered its decision on January 26, 1780, finding Arnold guilty of breaching the articles of war by permitting a vessel from an enemy port into Philadelphia and recommended that he be reprimanded by Washington. Howe was made commandant of the Continental Army fortifications at West Point on February 21, 1780. He held that command immediately prior to Benedict Arnold's conspiracy to turn over control of that stronghold to the British. Arnold and several supporters in Congress had eventually convinced Washington to give him command of the fortifications on August 3, 1780. Howe remained active in theupper Hudson River valley

The northern portion of the Hudson River valley in Upstate New York, generally that region extending from the first town below the headwaters of the Hudson River at North River, New York, North River to the last substantive waterfall preventing the ...

during the remainder of the war, particularly in overseeing his network of spies in the area, including double agent Joshua Hett Smith, who would later play a key role in Arnold's treason and prosecution. During this time, evidence arose implicating Howe in discussions with the British, though the evidence was dismissed by Washington as merely rumors stirred up by British General Henry Clinton. Howe served on the court-martial board that convicted of espionage and sentenced to death Major John André, the British officer tasked with facilitating Arnold's conspiracy.

Pennsylvania mutinies and war's end, 1781–1783

In 1781, Howe assisted in putting down thePompton Mutiny

The Pompton Mutiny, also referred to as the Federal Hill Rebellion, was a revolt of Continental Army troops at Pompton Camp in what was then Pompton Township, New Jersey, present-day Bloomingdale, New Jersey, that occurred on January 20, 1781, ...

in New Jersey, which was inspired by the slightly earlier Pennsylvania Line Mutiny

The Pennsylvania Line Mutiny was a mutiny of Continental Army soldiers, who demanded higher pay and better housing conditions, and was the cause of the legend and stories surrounding the American heroine Tempe Wick. The mutiny began on Janua ...

. Washington ordered Howe to surround the camp and arrange for the court-martial and execution of two of its ringleaders. In the fall of 1781, Howe requested permission to go with Washington to Virginia for what was anticipated to be the final campaign against the British, but Washington refused. Instead, Howe was required to appear before a court–martial in Philadelphia which was opened to inquire into Howe's actions in the defense of Savannah in 1778. The tribunal, led by Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who ...

, opened on December 7, 1781, and closed on January 23, 1782, acquitting Howe of any wrongdoing at Savannah with "the Highest Honor". Assistant Adjutant General John Carlisle ordered Howe to convene a court–martial to investigate the conduct of General Alexander McDougall

Alexander McDougall (1732 9 June 1786) was a Scottish-born American seaman, merchant, a Sons of Liberty leader from New York City before and during the American Revolution, and a military leader during the Revolutionary War. He served as a m ...

in the spring of 1782. McDougall was a personal friend of Howe's, but the tribunal convicted him of the minor offense of releasing confidential details from a council of war meeting in 1776 to persons who were not permitted to have such information. Again in 1783, Howe was called on to put down the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, which had caused the Continental Congress to flee Philadelphia.

Post-war career and death

After putting down the second Pennsylvania mutiny in 1783, Howe participated in the establishment of the Society of the Cincinnati and was the second officer to sign the national charter, with his signature appearing directly below that of von Steuben. Howe thereafter returned to his North Carolina plantation, Kendal, which was upriver from the more famousOrton Plantation

The Orton Plantation is a historic plantation house in the Smithville Township of Brunswick County, North Carolina, United States. Located beside the Cape Fear River between Wilmington and Southport, Orton Plantation is considered to be a nea ...

owned by Howe's distant relatives. Also in 1783, Howe became a founding member of the North Carolina Society of the Cincinnati and was a signatory to its "Institution" or charter. During much of 1783 and 1784, Howe returned frequently to Philadelphia, New York, and other cities in the northeast in an attempt to settle accounts and obtain back payments he claimed he was owed by Congress. He was again forced to mortgage his plantation but eventually received a monetary settlement from Congress of $7,000 in 1785.

During 1785, Howe was appointed by the Congress of the Confederation to establish treaties with several western Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

tribes but did not actually travel with commissioners George Rogers Clark, Richard Butler, and Samuel Holden Parsons

Samuel Holden Parsons (May 14, 1737 – November 17, 1789) was an American lawyer, jurist, generalHeitman, ''Officers of the Continental Army'', 428. in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and a pioneer to the Ohio Countr ...

, who finalized the Treaty of Fort Finney

Fort Finney was a fort built in Oct. 1785 at the mouth of the Great Miami River near the modern city of Cincinnati and named for Major Walter Finney who built the fort. The site was chosen to be midway between Falls of the Ohio and Limestone ( May ...

without Howe in 1786. Howe assisted Benjamin Smith in planning for the construction of Bald Head Light and actively worked to assist former Loyalists who sought to return to their prior lives in North Carolina by defending them against the judiciary of the state.

In the summer of 1786, he was elected a member of the North Carolina House of Commons

The North Carolina House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the North Carolina General Assembly. The House is a 120-member body led by a Speaker of the House, who holds powers similar to those of the President pro-tem in the North Ca ...

. On his way to a meeting of the legislative body, Howe fell ill, and died on December 14, 1786, in Bladen County. Howe's remains were buried on property he owned in what later became Columbus County, North Carolina

Columbus County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina, on its southeastern border. Its county seat is Whiteville. The 2020 census showed a loss of 12.9% of the population from that of 2010. As of the 2020 census, the popul ...

, although the exact location of his burial has not been discovered. A cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

was placed in Southport's Old Smithville Burying Ground honoring him and wife Sara.

Legacy

Howe has been remembered primarily in a negative light based on his lack of military successes and reputation, although North Carolina historian Hugh Rankin noted in a biographical sketch that "his opportunities came at times when he did not have proper field strength to gain favorable recognition." During the 1903 session of theUnited States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

, Congressman John Dillard Bellamy

John Dillard Bellamy Jr. (March 24, 1854 – September 25, 1942) was a United States Democratic Party, Democratic United States House of Representatives, U.S. Congressman from North Carolina between 1899 and 1903.

Born in Wilmington, North Car ...

introduced a bill to erect an equestrian statue of Howe in Wilmington in order to commemorate the general's service; this bill was not passed. Note that the article incorrectly cites the date as 1908. In 1940, the State of North Carolina cast and erected a highway historical marker

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, typically attached to a wall, stone, or other ...

to commemorate Howe's service. The marker stands on North Carolina Highway 133 in Belville, North Carolina

Belville is a town in Brunswick County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 1,936 at the 2010 census, up from 285 in 2000. It is part of the Wilmington, NC metropolitan area.

History

Belville was incorporated as a town in 1977.

Ge ...

. The 1955 film ''The Scarlet Coat

''The Scarlet Coat '' is a 1955 American historical drama and swashbuckler in Eastmancolor and CinemaScope released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, produced by Nicholas Nayfack, directed by John Sturges. It stars Cornel Wilde, Michael Wilding, George Sa ...

'' featured a performance by actor John McIntire

John Herrick McIntire (June 27, 1907 – January 30, 1991) was an American character actor who appeared in 65 theatrical films and many television series. McIntire is well known for having replaced Ward Bond, upon Bond's sudden death in Novem ...

as Howe during the height of the Benedict Arnold conspiracy.

Evidence of attempted treason

Several scholars have raised questions regarding Howe's actions as the unofficial spymaster of the Hudson Valley, all of which center on evidence that suggests Howe attempted to bargain with the British in exchange for a commission as an officer in the regular British Army, similar to the bargain struck by Benedict Arnold in 1780. As early as 1776, after Howe was appointed a brigadier general, a Loyalist merchant named Henry Kelly advisedSecretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, British Cabinet government minister, minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various British Empire, colonial dependencies.

Histor ...

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville, PC (26 January 1716 – 26 August 1785), styled The Honourable George Sackville until 1720, Lord George Sackville from 1720 to 1770 and Lord George Germain from 1770 to 1782, was a British soldier and p ...

that Howe could be easily tempted to join the British, and further claimed that Howe could offer a great deal to the British in their war effort.

In 1780, after Benedict Arnold's attempted treason had been exposed, Captain Beesly Edgar Joel, a British defector and former officer in the British Army, claimed that another officer besides Arnold had attempted to defect, and after interrogation Joel named Howe as that officer. Joel cited Edmund Fanning, William Tryon's secretary, as the source for his information. Joel further described Howe's method of communicating with the British, which was by means of a frequently imprisoned-and-exchanged prisoner who would convey messages between the parties. While neither Washington or the Congressional Board of War

The Board of War, also known as the Board of War and Ordinance, was created by the Second Continental Congress as a special standing committee to oversee the American Continental Army's administration and to make recommendations regarding the ar ...

believed Joel's story due to their suspicion of Joel as a British spy, Joel was later commissioned by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and the Virginia government to lead a Patriot militia unit against Loyalists in that state. Furthermore, William Smith, a New York Loyalist and the brother of Howe's agent and Arnold's co-conspirator Joshua Hett Smith, noted in his diary on April 29, 1780, that his brother, Thomas Smith, had been informed that a commissary had come over to the British with "information" from the Patriots in much the same manner as Joel had described. On September 28, 1780, William Smith told Henry Clinton that he believed "Bob" Howe would be willing to turn on the Patriots.

Later historians, including Douglas Southall Freeman

Douglas Southall Freeman (May 16, 1886 – June 13, 1953) was an American historian, biographer, newspaper editor, radio commentator, and author. He is best known for his multi-volume biographies of Robert E. Lee and George Washington, for both ...

, have frequently dismissed allegations that Howe attempted to defect, believing them to have been fabrications used by Joel to ingratiate himself with the Patriot government. The only full-length book treatment of Howe's life discusses the allegations of attempted treason in a single page. On the other hand, Freeman's judgment was based primarily on Washington's assessment of the allegations, but Washington did not have access to the potentially corroborating evidence in William Smith's diary. Another possibility is that Howe had merely attempted to spread word among the British of his possible treason in order to conceal his management of the vast spy network at his control; this tactic was utilized by other spymasters in Continental employ such as Philip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 18, 1804) was an American general in the Revolutionary War and a United States Senator from New York. He is usually known as Philip Schuyler, while his son is usually known as Philip J. Schuyler.

Born in Alb ...

. Philip Ranlet, an American historian who studied Howe's career and motivations, has contrasted Schuyler's otherwise shining reputation with Howe's record of failures and draws the conclusion that Howe likely was attempting to defect. To date, no firm evidence exists which either absolves Howe or proves him guilty of attempted treason.

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Howe, Robert 1732 births 1786 deaths Continental Army generals Continental Army officers from North Carolina American duellists American slave owners Members of the North Carolina House of Representatives People from New Hanover County, North Carolina People of colonial North Carolina Burials in North Carolina Members of the North Carolina Provincial Congresses Members of the North Carolina House of Burgesses 18th-century American politicians