Richard Glücks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Glücks (; 22 April 1889 – 10 May 1945) was a high-ranking German

Glücks joined the

Glücks joined the

Glücks's responsibilities at first mainly covered the use of concentration camp inmates for

Glücks's responsibilities at first mainly covered the use of concentration camp inmates for  In July 1942, he participated in a planning meeting with Himmler on the topic of medical experiments on camp inmates. From several visits to the

In July 1942, he participated in a planning meeting with Himmler on the topic of medical experiments on camp inmates. From several visits to the

Holocaust Research Project.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gluecks, Richard 1889 births 1945 suicides People from Mönchengladbach Nazi Party politicians SS-Gruppenführer People from the Rhine Province Nazis who committed suicide in Germany Suicides by cyanide poisoning Holocaust perpetrators 20th-century Freikorps personnel Waffen-SS personnel German Army personnel of World War I 1945 deaths

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

official in the SS. From November 1939 until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he was Concentration Camps Inspector (CCI), which became ''Amt D: Konzentrationslagerwesen'' under the WVHA in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. As a direct subordinate of Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, he was responsible for the forced labour of the camp inmates, and was also the supervisor for the medical practices in the camps, ranging from human experimentation to the implementation of the "Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

", in particular the mass murder

Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...

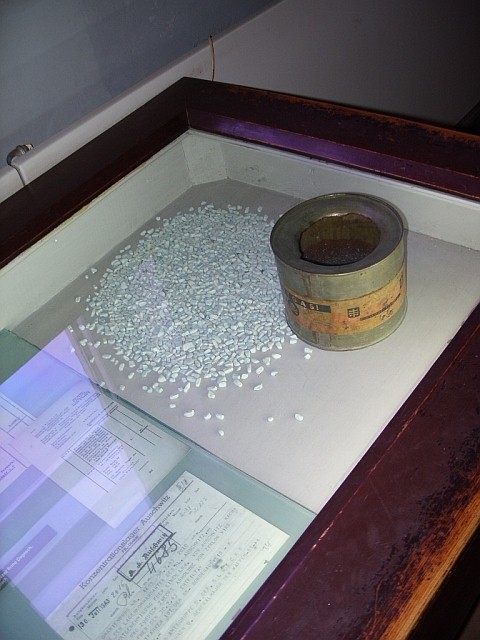

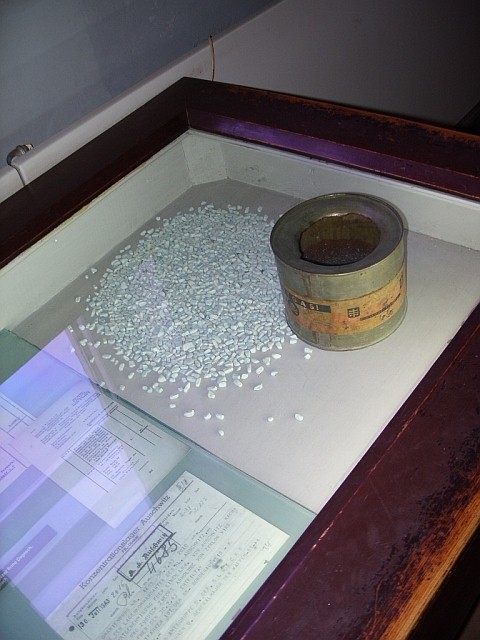

of inmates with Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

gas. After Germany capitulated, Glücks committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

by swallowing a potassium cyanide

Potassium cyanide is a compound with the formula KCN. This colorless crystalline salt, similar in appearance to sugar, is highly soluble in water. Most KCN is used in gold mining, organic synthesis, and electroplating. Smaller applications includ ...

capsule.

Early life

Glücks was born 1889, in Odenkirchen (now part ofMönchengladbach

Mönchengladbach (, li, Jlabbach ) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located west of the Rhine, halfway between Düsseldorf and the Dutch border.

Geography Municipal subdivisions

Since 2009, the territory of Mönchengladbac ...

) in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

. Having completed gymnasium in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

, he worked in his father's business, a fire insurance agency. In 1909, Glücks joined the army for one year as a volunteer, serving in the artillery. In 1913, he was in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, and later moved to Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

as a trader. When World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

broke out, Glücks returned to Germany under a false identity on a Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

ship in January 1915 and joined the army again. During the war, he eventually became the commander of an artillery unit and was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

I and II. Glücks fought at the Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun (french: Bataille de Verdun ; german: Schlacht um Verdun ) was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front in France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north ...

and the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

. After the war, he became a liaison officer between the German forces and the Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control

The term Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control was used in a series of peace treaties concluded after the First World War (1914–1918) between different countries. Each of these treaties was concluded between the Principal Allied and A ...

, the allied body for controlling the restrictions placed upon Germany in the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

regarding re-armament and strength of their armed forces. Until 1924, he stayed in that position, before joining the staff of the 6th Prussian Division. He also served in the ''Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, regar ...

''.

Rise under the Nazi regime

Glücks joined the

Glücks joined the NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

in 1930 and two years later, the SS. From 6 September 1933 to 20 June 1935 he was a member of the staff of the SS-Group "West" and rose to the rank of an ''SS-Sturmbannführer

__NOTOC__

''Sturmbannführer'' (; ) was a Nazi Party paramilitary rank equivalent to major that was used in several Nazi organizations, such as the SA, SS, and the NSFK. The rank originated from German shock troop units of the First World War ...

''. While lacking in charisma, historian Nikolaus Wachsmann claims Glücks possessed an "abundance of ideological commitment." On 1 April 1936 he became the chief of staff to Theodor Eicke

Theodor Eicke (17 October 1892 – 26 February 1943) was a senior SS functionary and Waffen SS divisional commander during the Nazi era. He was one of the key figures in the development of Nazi concentration camps. Eicke served as the seco ...

, who was then Concentration Camps Inspector and head of the ''SS- Wachverbände''.

Concentration Camps Inspector

When Eicke became field commander of theSS Division Totenkopf

The 3rd SS Panzer Division "Totenkopf" (german: 3. SS-Panzerdivision "Totenkopf") was an elite division of the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany during World War II, formed from the Standarten of the SS-TV. Its name, ''Totenkopf'', is German for "de ...

during the summer of 1939, Glücks was promoted by Himmler on 15 November 1939 as Eicke's successor to the post of Concentration Camps Inspector. As the Concentration Camps Inspector, Glücks was directly subordinate to Himmler—as Eicke had been—but, in contrast with the warm relation between Himmler and the older Eicke, Glücks only rarely met with Himmler, who promoted him not for his leadership competencies but for his ability to "provide the administrative continuity" with Eicke's policies. Less a reflection of Glücks's energy and aptitude, his rise in power was more about Eicke's ineffectual managerial skill, according to historian Michael Thad Allen. Glücks made few changes once taking over, leaving the organizational structure intact as Eicke had set it up; the same uncompromising rigidity was carried out at the camps—there was no rehabilitation and no effort to exploit the working potential of inmates. Because Glücks never served inside a concentration camp, some senior camp members were suspicious and considered him nothing more than a desk-side bureaucrat. In terms of his leadership style, he preferred men of action and allowed them some autonomy in operating their respective camps. Historian Robert Lewis Koehl described Glücks as "unimaginative, lacking in energy if not lazy," and even "unperceptive," which may account to some extent for his hands-off approach.

Glücks's responsibilities at first mainly covered the use of concentration camp inmates for

Glücks's responsibilities at first mainly covered the use of concentration camp inmates for forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. In this phase, he urged camp commandants to lower the death rate in the camps, as it went counter to the economic objectives his department was to fulfill. Other orders of his were to ask for the inmates to be made to work continuously. At the same time, it was Glücks who recommended on 21 February 1940, Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, a former Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n cavalry barracks, as a suitable site for a new concentration camp to Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

. Glücks accompanied Himmler and several chief directors of I.G. Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (), commonly known as IG Farben (German for 'IG Dyestuffs'), was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agfa, ...

on 1 March 1941 for a visit to Auschwitz, where it was decided that the camp would be expanded to accommodate up to 30,000 prisoners, an additional camp would be established at nearby Birkenau capable of housing 100,000 POWs, and that a factory would be constructed in proximity with the camp prisoners placed at I.G. Farben's disposal.

On 20 April 1941 Glücks was promoted to the rank of an ''SS-Brigadeführer

''Brigadeführer'' (, ) was a paramilitary rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) that was used between the years of 1932 to 1945. It was mainly known for its use as an SS rank. As an SA rank, it was used after briefly being known as ''Untergruppenf� ...

'' and in November 1943, Glücks was made ''SS-Gruppenführer'' and a ''Generalleutnant'' of the Waffen-SS. From 1942 on, Glücks was increasingly involved in the implementation of the "Final Solution", along with Oswald Pohl

Oswald Ludwig Pohl (; 30 June 1892 – 7 June 1951) was a German SS functionary during the Nazi era. As the head of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office and the head administrator of the Nazi concentration camps, he was a key figure in ...

. To oversee the coordination of camp related activities, which varied from the medical concerns of personnel and prisoners, the status of construction projects, and the progress of extermination operations, Glücks, along with other senior SS camp managers, attended weekly meetings conducted by Pohl. Glücks never attempted to outshine his superior and was quite aware of his subordination to Pohl.

Just a few days after the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, Himmler ordered Glücks to prepare the camps for the immediate arrival of 100,000 Jewish men and 50,000 women being evacuated from the Reich as labourers in lieu of the diminishing availability of Russian prisoners. In February 1942, the CCI became ''Amt D'' of the '' Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt'' (SS Economic and Administrative Department; WVHA) under ''SS-Obergruppenführer

' (, "senior group leader") was a paramilitary rank in Nazi Germany that was first created in 1932 as a rank of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) and adopted by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) one year later. Until April 1942, it was the highest commissio ...

'' Oswald Pohl

Oswald Ludwig Pohl (; 30 June 1892 – 7 June 1951) was a German SS functionary during the Nazi era. As the head of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office and the head administrator of the Nazi concentration camps, he was a key figure in ...

. Glücks continued to manage the camp administration until the end of the war. Therefore, the entire concentration camp system was placed under the authority of the WVHA with the Inspector of Concentration Camps now a subordinate to the Chief of the WVHA. By March 1942, Glücks was routinely receiving direct instructions from the head engineer and SS General Hans Kammler

Hans Kammler (26 August 1901 – 1945 ssumed was an SS-Obergruppenführer responsible for Nazi civil engineering projects and its top secret weapons programmes. He oversaw the construction of various Nazi concentration camps before being put ...

, to meet the productivity demands of SS engineers.

In July 1942, he participated in a planning meeting with Himmler on the topic of medical experiments on camp inmates. From several visits to the

In July 1942, he participated in a planning meeting with Himmler on the topic of medical experiments on camp inmates. From several visits to the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

s, Glücks was well aware of the mass murder

Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...

s and other atrocities committed there. Correspondingly, Auschwitz Kommandant Rudolf Höss

Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss (also Höß, Hoeß, or Hoess; 25 November 1901 – 16 April 1947) was a German SS officer during the Nazi era who, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, was convicted for war crimes. Höss was the longest-serving comm ...

routinely informed Glücks on the status of the extermination activities. During one of his inspection-tour visits to Auschwitz in 1943, Glücks complained about the unfavorable location of the crematoria since all types of people would be able to "gaze" at the structures. Responding to this observation, Höss ordered a row of trees planted between Crematorias I and II. When visits from high officials from the Reich or the Nazi Party took place, the administration was instructed by Glücks to avoid showing the crematorias to them; if questions arose about smoke coming from the chimneys, the installation personnel were to tell the visitors that corpses were being burned as a result of epidemics.

Sometime in December 1942, after discovering 70,000 out of 136,000 incoming prisoners had died almost as fast as they arrived, he issued a directive to the camp doctors, which stated, "The best camp doctor in a concentration camp is that doctor who holds the work capacity among inmates at its highest possible level ... Toward this end it is necessary that the camp doctors take a personal interest and appear on location at work sites."

Before the death marches

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

of early 1945 started, Glücks reiterated a directive from July 1944, which emphasized to camp commanders that during "emergency situations," they were to follow the instructions of the regional HSSPF (''Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer'') commanders. Between 250,000 and 400,000 additional people died as a result of these death marches.

According to historian Leni Yahil

Leni Yahil (1912–2007), née Leni Westphal, was a German-born Israeli historian, specializing in the Holocaust and Danish Jewry.

Early life

Leni was born in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 1912, and was raised in Potsdam, Germany. She was a sixth-g ...

, Glücks was "the RSHA man responsible for the entire network of concentration camps", and his authority extended to the largest and most infamous of them all, Auschwitz. From what historian Martin Broszat relates, nearly all the important matters concerning the concentration camps were "decided directly between the Inspector of Concentration Camps and the ''Reichsführer-SS''." In January 1945, Glücks was decorated for his contributions to the Reich in managing the fifteen largest camps and the five-hundred satellite camps which employed upwards of 40,000 members of the SS. Glücks' role in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

"cannot be over-emphasized" as he, together with Pohl, oversaw the entire Nazi camp system and the persecution network it represented.

Death

When the WVHA offices inBerlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

were destroyed by Allied bombing on 16 April 1945, the WVHA was moved to Born on Darß The Darß or Darss is the middle part of the peninsula of Fischland-Darß-Zingst on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The peninsula's name is of Slavic origin. There is a large forest in the ...

in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

on the Baltic sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. Owing to the advances of the Red Army forces, Glücks and his wife fled to Flensburg

Flensburg (; Danish, Low Saxon: ''Flensborg''; North Frisian: ''Flansborj''; South Jutlandic: ''Flensborre'') is an independent town (''kreisfreie Stadt'') in the north of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Flensburg is the centre of the ...

.

After the capitulation of Germany, he is believed to have committed suicide on 10 May 1945 by swallowing a capsule of potassium cyanide

Potassium cyanide is a compound with the formula KCN. This colorless crystalline salt, similar in appearance to sugar, is highly soluble in water. Most KCN is used in gold mining, organic synthesis, and electroplating. Smaller applications includ ...

at the Mürwik naval base in Flensburg

Flensburg (; Danish, Low Saxon: ''Flensborg''; North Frisian: ''Flansborj''; South Jutlandic: ''Flensborre'') is an independent town (''kreisfreie Stadt'') in the north of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Flensburg is the centre of the ...

-Mürwik

Mürwik ( da, Mørvig) is a community of Flensburg in the north of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Situated on the east side of the Flensburg Firth, it is on the Angeln peninsula. Mürwik is the location of the Naval Academy at Mürwik, w ...

, although the lack of official records or photos gave rise to speculation about his ultimate fate.

Fictional references

Glücks appears as a character in the 1972Frederick Forsyth

Frederick McCarthy Forsyth (born 25 August 1938) is an English novelist and journalist. He is best known for thrillers such as ''The Day of the Jackal'', ''The Odessa File'', '' The Fourth Protocol'', '' The Dogs of War'', ''The Devil's Alter ...

novel ''The Odessa File

''The Odessa File'' is a thriller by English writer Frederick Forsyth, first published in 1972, about the adventures of a young German reporter attempting to discover the location of a former SS concentration-camp commander.

The name ODESSA is ...

'' along with its 1974 film adaptation. In the novel, which is set in 1963, he is depicted as still being alive and the head of ODESSA

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, which is determined to destroy the State of Israel nearly two decades after the end of World War II.

See also

* List SS-Gruppenführer *List of SS personnel

Between 1925 and 1945, the German ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) grew from eight members to over a quarter of a million ''Waffen-SS'' and over a million ''Allgemeine-SS'' members. Other members included the ''SS-Totenkopfverbände'' (SS-TV), which ran t ...

* Pohl Trial

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team (2009). "Richard Glucks as described by Rudolf Höss" aHolocaust Research Project.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gluecks, Richard 1889 births 1945 suicides People from Mönchengladbach Nazi Party politicians SS-Gruppenführer People from the Rhine Province Nazis who committed suicide in Germany Suicides by cyanide poisoning Holocaust perpetrators 20th-century Freikorps personnel Waffen-SS personnel German Army personnel of World War I 1945 deaths