Richard Bellingham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

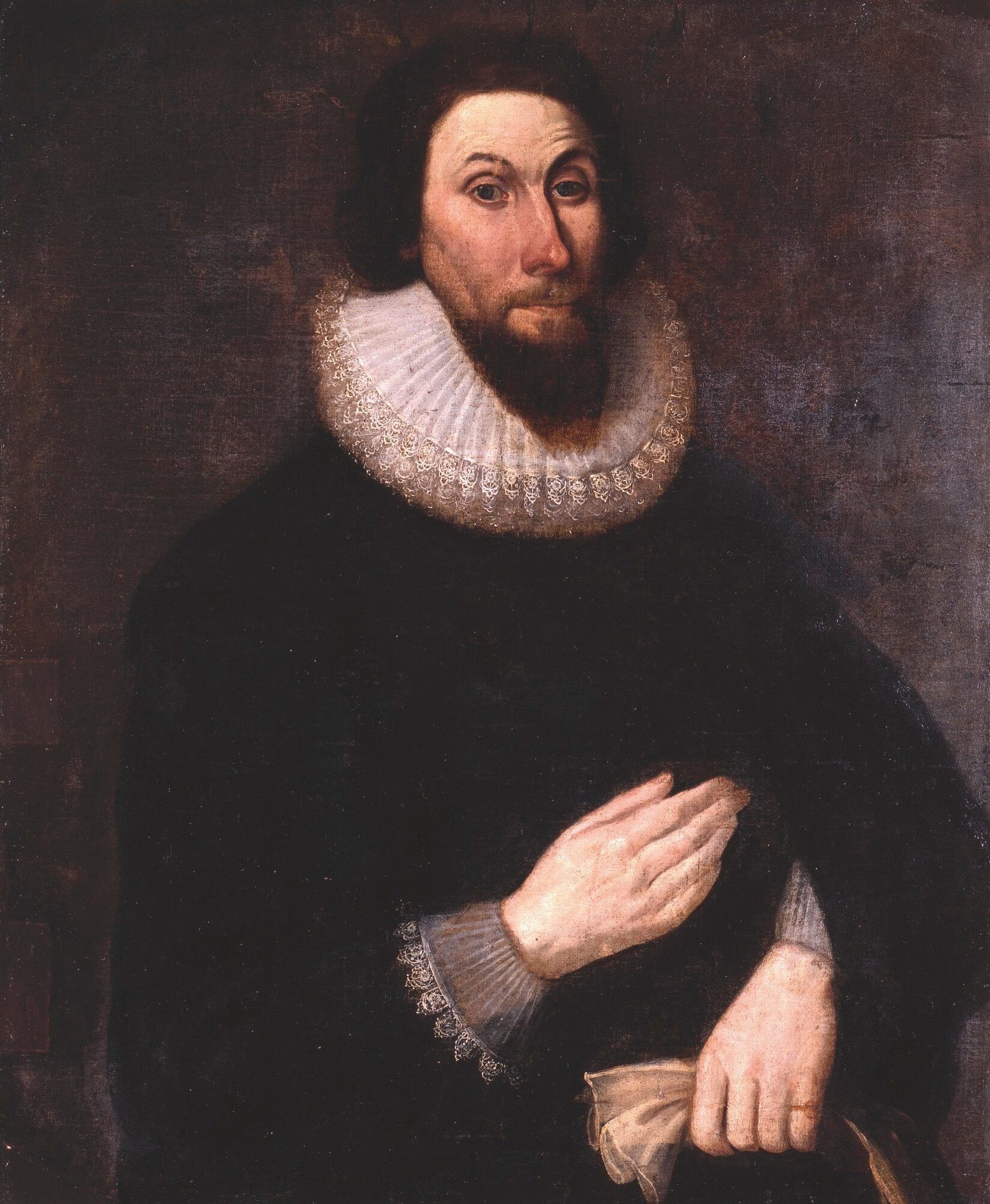

Richard Bellingham (c. 1592 – 7 December 1672) was a colonial magistrate, lawyer, and several-time governor of the

Bellingham immediately assumed a prominent role in the colony, serving on the committee that oversaw the affairs of Boston (a precursor to the board of selectmen). In this role he participated in the division of community lands that included the establishment of

Bellingham immediately assumed a prominent role in the colony, serving on the committee that oversaw the affairs of Boston (a precursor to the board of selectmen). In this role he participated in the division of community lands that included the establishment of  In the 1640s constitutional issues concerning the power of the assistants arose. In a case involving an escaped pig, the assistants ruled in favor of a merchant who had allegedly taken a widow's errant animal. She appealed to the general court, which ruled in her favor. The assistants then asserted their right to veto the general court's decision, sparking the controversy. John Winthrop argued that the assistants, as experienced magistrates, must be able to check the democratic institution of the general court, because "a democracy is, amongst most civil nations, accounted the meanest and worst of all forms of government." Bellingham was one of only two assistants (the other was Richard Saltonstall) who opposed the final decision that the assistants' veto should stand. Bellingham and Saltonstall were often in a minority that opposed the more conservative views of Winthrop and

In the 1640s constitutional issues concerning the power of the assistants arose. In a case involving an escaped pig, the assistants ruled in favor of a merchant who had allegedly taken a widow's errant animal. She appealed to the general court, which ruled in her favor. The assistants then asserted their right to veto the general court's decision, sparking the controversy. John Winthrop argued that the assistants, as experienced magistrates, must be able to check the democratic institution of the general court, because "a democracy is, amongst most civil nations, accounted the meanest and worst of all forms of government." Bellingham was one of only two assistants (the other was Richard Saltonstall) who opposed the final decision that the assistants' veto should stand. Bellingham and Saltonstall were often in a minority that opposed the more conservative views of Winthrop and

The reaction by Charles to this was to issue an order in 1666 demanding that Bellingham, since he was then governor, and

The reaction by Charles to this was to issue an order in 1666 demanding that Bellingham, since he was then governor, and

Richard Bellingham died on 7 December 1672. He was the last surviving signer of the colonial charter, and was buried in Boston's

Richard Bellingham died on 7 December 1672. He was the last surviving signer of the colonial charter, and was buried in Boston's  Bellingham was immortalized as a fictional character in

Bellingham was immortalized as a fictional character in

The Governor Bellingham~Cary House Association web site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bellingham, Richard 1592 births 1672 deaths Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford Colonial governors of Massachusetts Lieutenant Governors of colonial Massachusetts Politicians from Chelsea, Massachusetts Massachusetts lawyers English MPs 1628–1629 English lawyers 17th-century English lawyers 17th-century American people American Puritans 17th-century Protestants Burials at Granary Burying Ground Lawyers from Chelsea, Massachusetts

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

, and the last surviving signatory of the colonial charter at his death. A wealthy lawyer in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

prior to his departure for the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

in 1634, he was a liberal political opponent of the moderate John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

, arguing for expansive views on suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

and lawmaking, but also religiously somewhat conservative, opposing (at times quite harshly) the efforts of Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

and Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

to settle in the colony. He was one of the architects of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties was the first legal code established in New England, compiled by Puritan minister Nathaniel Ward. The laws were established by the Massachusetts General Court in 1641. The Body of Liberties begins by establishin ...

, a document embodying many sentiments also found in the United States Bill of Rights

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections rais ...

.

Although he was generally in the minority during his early years in the colony, he served ten years as colonial governor, most of them during the delicate years of the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to be ...

, when King Charles II scrutinized the behavior of the colonial governments. Bellingham notably refused a direct order from the king to appear in England, an action that may have contributed to the eventual revocation of the colonial charter in 1684.

He was twice married, survived by his second wife and his only son Samuel. He died in 1672, leaving an estate in present-day Chelsea, Massachusetts

Chelsea is a city in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Massachusetts, United States, directly across the Mystic River from the city of Boston. As of the 2020 census, Chelsea had a population of 40,787. With a total area of just 2.46 s ...

, and a large house in Boston. The estate became embroiled in legal action lasting more than 100 years after his will was challenged by his son and eventually set aside. Bellingham is immortalized in Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

's ''The Scarlet Letter

''The Scarlet Letter: A Romance'' is a work of historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym ...

'' and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely transl ...

's ''The New England Tragedies'', both of which fictionalize events from colonial days.

Early life

Richard Bellingham, the son of William Bellingham and Frances Amcotts, was born inLincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

, England, in about 1592. The family was apparently well to do; they resided in a manor at Bromby Wood near Scunthorpe

Scunthorpe () is an industrial town and unparished area in the unitary authority of North Lincolnshire in Lincolnshire, England of which it is the main administrative centre. Scunthorpe had an estimated total population of 82,334 in 2016. A pre ...

. He studied law at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

, matriculating on 1 December 1609.Anderson, p. 1:243 In 1625 he was elected Recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

(the highest community legal post) of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, a position he held until 1633. He represented Boston as a member of Parliament in 1628 and 1629. He was first married to Elizabeth Backhouse of Swallowfield

Swallowfield is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England, about south of Reading, and north of the county boundary with Hampshire.

Geography

The civil parish of Swallowfield also includes the nearby villages of Riseley and Farley Hi ...

, Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Berk ...

, with whom he had a number of children, although only their son Samuel survived to adulthood.

In 1628 he became an investor in the Massachusetts Bay Company

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, and was one of the signers of the land grant issued to it by the Plymouth Council for New England

The Council for New England was a 17th-century English joint stock company that was granted a royal charter to found colonial settlements along the coast of North America. The Council was established in November of 1620, and was disbanded (althou ...

. His name also appears on the royal charter issued for the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

in 1629. In 1633 he resigned as recorder of Boston and began selling off his properties. The next year he sailed for the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

with his wife and son;Goss, p. 262 Elizabeth died not long after their arrival in Boston, Massachusetts.

Massachusetts Bay Colony

Bellingham immediately assumed a prominent role in the colony, serving on the committee that oversaw the affairs of Boston (a precursor to the board of selectmen). In this role he participated in the division of community lands that included the establishment of

Bellingham immediately assumed a prominent role in the colony, serving on the committee that oversaw the affairs of Boston (a precursor to the board of selectmen). In this role he participated in the division of community lands that included the establishment of Boston Common

The Boston Common (also known as the Common) is a public park in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest city park in the United States. Boston Common consists of of land bounded by Tremont Street (139 Tremont St.), Park Street, Beacon ...

. Not long after his arrival, he purchased the ferry service between Boston and Winnessimmett (present-day Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

) from Samuel Maverick

Samuel Augustus Maverick (July 23, 1803 – September 2, 1870) was a Texas lawyer, politician, land baron and signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence. His name is the source of the term "maverick," first cited in 1867, which means "indepe ...

, along with tracts of land that encompass much of Chelsea. In addition to his mansion house in Boston, he also established a country home near the ferry in Winnessimmett. A house he built in 1659 still stands in Chelsea, and is known as the Bellingham-Cary House.

For many years he was elected to the colony's council of assistants, which advised the governor on legislative matters and served as a judicial body, and he also served several terms as colonial treasurer. He was first elected deputy governor of the colony in 1635, at a time when the dominant John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

was out of favor, and was elected to the post again in 1640. In 1637, during the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

, he was one of the magistrates that sat during the trial of Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her ...

, and voted for her to be banished from the colony. According to historian Francis Bremer, Bellingham was somewhat brash and antagonistic, and he and Winthrop repeatedly clashed on political matters. During these early years Bellingham was chosen to be on the first board of overseers of Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

. He also contributed to the development of the colony's first legal code, known as the Massachusetts Body of Liberties

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties was the first legal code established in New England, compiled by Puritan minister Nathaniel Ward. The laws were established by the Massachusetts General Court in 1641. The Body of Liberties begins by establishin ...

. This work was opposed and repeatedly stalled by Winthrop, who favored a common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

approach to legislation.

In 1641 Bellingham was elected governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

for the first time, running against Winthrop. The Body of Liberties was formally adopted during his term.Bremer, p. 305 However, he served for just one year, and was replaced by Winthrop in 1642.Moore, pp. 336–337 Bellingham's defeat may have been caused in part by the scandalous impropriety surrounding his second marriage. A friend who was a guest in his house had been courting Penelope Pelham, a young woman of twenty. According to Winthrop, Bellingham, now 50 and a widower, won her heart, and, without waiting for the formalities of the banns of marriage

The banns of marriage, commonly known simply as the "banns" or "bans" (from a Middle English word meaning "proclamation", rooted in Frankish and thence in Old French), are the public announcement in a Christian parish church, or in the town cou ...

, officiated at his own wedding. When the issue came before the colonial magistrates, Bellingham (as the governor and chief magistrate) refused to step down from the bench to face the charges, thus bringing the matter to a somewhat awkward end. Bellingham's term in office was characterized by Winthrop as extremely difficult: "The General Court was full of uncomfortable agitations and contentions by reason of Bellingham's unfriendliness to some other magistrates. He set himself in an opposite frame to them in all proceedings, which did much to retard business".

In the 1640s constitutional issues concerning the power of the assistants arose. In a case involving an escaped pig, the assistants ruled in favor of a merchant who had allegedly taken a widow's errant animal. She appealed to the general court, which ruled in her favor. The assistants then asserted their right to veto the general court's decision, sparking the controversy. John Winthrop argued that the assistants, as experienced magistrates, must be able to check the democratic institution of the general court, because "a democracy is, amongst most civil nations, accounted the meanest and worst of all forms of government." Bellingham was one of only two assistants (the other was Richard Saltonstall) who opposed the final decision that the assistants' veto should stand. Bellingham and Saltonstall were often in a minority that opposed the more conservative views of Winthrop and

In the 1640s constitutional issues concerning the power of the assistants arose. In a case involving an escaped pig, the assistants ruled in favor of a merchant who had allegedly taken a widow's errant animal. She appealed to the general court, which ruled in her favor. The assistants then asserted their right to veto the general court's decision, sparking the controversy. John Winthrop argued that the assistants, as experienced magistrates, must be able to check the democratic institution of the general court, because "a democracy is, amongst most civil nations, accounted the meanest and worst of all forms of government." Bellingham was one of only two assistants (the other was Richard Saltonstall) who opposed the final decision that the assistants' veto should stand. Bellingham and Saltonstall were often in a minority that opposed the more conservative views of Winthrop and Thomas Dudley

Thomas Dudley (12 October 157631 July 1653) was a New England colonial magistrate who served several terms as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Dudley was the chief founder of Newtowne, later Cambridge, Massachusetts, and built the tow ...

. In 1648 Bellingham sat on a committee established to demonstrate that the colony's legal codes were not "repugnant to the laws of England", as called for by the colonial charter.

In 1650, when Bellingham was an assistant, he concurred in the judicial decision banning William Pynchon

William Pynchon (October 11, 1590 – October 29, 1662) was an English colonist and fur trader in North America best known as the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, USA. He was also a colonial treasurer, original patentee of the Massachu ...

's ''The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption'', which expressed views many Puritans considered heretical. Bellingham was again elected governor in 1654, and again in May 1665 after the death of Governor John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

. He was thereafter annually re-elected to the post until his death, ultimately serving a total of ten years as governor and thirteen as deputy governor. While he was deputy to Endecott in 1656, a boat carrying several Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

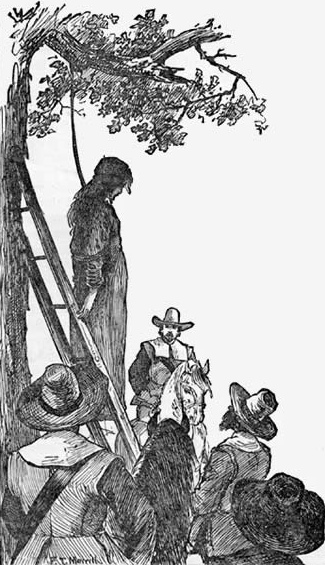

s arrived in Boston. Since Endecott was in Salem at the time, Bellingham directed the government's reaction to their arrival. Because Quakerism was anathema to the Puritans, the Quakers were confined to the ship, their belongings were searched, and books promoting their religion were destroyed. After five weeks of captivity, they were sent back to England. During Endecott's administration the penalties for Quakers defying banishment from the colony were made progressively harsher, until they included the imposition of the death penalty for repeat offenders. Under these laws, four Quakers were put to death for returning to the colony after their banishment. Quaker historians have also been harsh in their assessments of Bellingham. After Massachusetts authorities agreed that the death penalty did not work (it had long term negative consequences, feeding perceptions of Massachusetts intransigence), the law was modified to reduce the penalties to branding and whipping.

English Restoration

The 1640s and 1650s in England were a time of great turmoil. TheEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

led to the establishment of the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

and eventually the Protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

. In this period, Massachusetts was generally sympathetic to Cromwell and the Parliamentary cause. With the restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

of Charles II to the throne in 1660, all of the colonies, and Massachusetts in particular, came under his scrutiny. In 1661 he issued a ''mandamus

(; ) is a judicial remedy in the form of an order from a court to any government, subordinate court, corporation, or public authority, to do (or forbear from doing) some specific act which that body is obliged under law to do (or refrain from ...

'' forbidding further persecution of the Quakers. He also requested specific changes to be made to Massachusetts laws to increase suffrage and tolerance for other Protestant religious practices, actions that were resisted or ignored during the Endecott administration. Charles finally sent royal commissioners to New England in 1664 to enforce his demands, but Massachusetts, of all the New England colonies, was the most recalcitrant, refusing all of the substantive demands or enacting changes that only superficially addressed the issues.

The reaction by Charles to this was to issue an order in 1666 demanding that Bellingham, since he was then governor, and

The reaction by Charles to this was to issue an order in 1666 demanding that Bellingham, since he was then governor, and William Hathorne

William Hathorne (–1681) was a widely influential man in early New England. He arrived on the ship Arbella.Anderson, Robert, ''The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England, 1620-1633,'' Entry for William Hathorne, New England Hist ...

, the speaker of the general court, travel to England to answer for the colony's behavior. The issue of how to answer this demand divided the colony, with petitions from a cross-section of the colony's population calling for the magistrates to obey the king's demand. The debate also introduced a long-term rift in the council of assistants between hardliners wanting to resist the king's demands at all costs and moderates who thought the king's demands should be accommodated. Bellingham sided with the hardliners and the decision was reached to send the king a letter. The letter questioned whether the request actually originated with the king, protested that the colony was loyal to him, and claimed the magistrates had already explained fully why they were unable to comply with the king's demands. The magistrates further pacified the angered sovereign by sending over a ship full of masts as a gift (New England was a valuable source of timber for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

).Partridge, p. 11 Distracted by the war with the Dutch and domestic politics, Charles did not pursue the issue further until after Bellingham's death, though for numerous reasons the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter was finally voided in 1684.Doyle, p. 151

Death and legacy

Richard Bellingham died on 7 December 1672. He was the last surviving signer of the colonial charter, and was buried in Boston's

Richard Bellingham died on 7 December 1672. He was the last surviving signer of the colonial charter, and was buried in Boston's Granary Burying Ground

The Granary Burying Ground in Massachusetts is the city of Boston's third-oldest cemetery, founded in 1660 and located on Tremont Street. It is the final resting place for many notable Revolutionary War-era patriots, including Paul Revere, the ...

. He was survived by his son Samuel from his first marriage and his second wife Penelope, who outlived him by 30 years. His landholdings at Winnessimmett became tied up in legal action lasting more than 100 years, and involved court and procedural decisions on both sides of the Atlantic to resolve. Under the terms of his will, some of his properties in Winnessimmett were set aside for religious uses. His son challenged the will, which was eventually set aside. The litigation continued, carried on by his heirs and succeeding owners and occupants of the properties, and was finally concluded in 1785. The town of Bellingham, Massachusetts

Bellingham () is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 16,945 at the 2020 census. The town sits on the southwestern fringe of Metropolitan Boston, along the rapidly growing "outer belt" that is Route 495. It ...

is named in his honor, and a number of features in Chelsea, including a square, a street, and a hill, bear the name Bellingham.

Bellingham was immortalized as a fictional character in

Bellingham was immortalized as a fictional character in Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

's ''The Scarlet Letter

''The Scarlet Letter: A Romance'' is a work of historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym ...

'', as the brother of Ann Hibbins

Ann Hibbins (also spelled Hibbons or Hibbens) was a woman executed for witchcraft in Boston, Massachusetts, on June 19, 1656. Her death by hanging was the third for witchcraft in Boston and predated the Salem witch trials of 1692.Poole, William F. ...

, a woman who was executed (in real life in 1656, as well as in the book) for practicing witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

.''Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society'', p. 186 There are apparently no contemporary references to Mrs. Hibbins as Bellingham's sister—Hawthorne's formation of this connection appears to be based on a footnote in James Savage's 1825 edition of John Winthrop's journals, and a genealogical tree of the Bellinghams published early in the 20th century does not mention her. However, Ann Hibbins' second husband, William Hibbins, was first married to Richard Bellingham's sister Hester but she died a year later and was buried in England. Bellingham also appears in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely transl ...

's ''The New England Tragedies'', which fictionalizes events dealing with the Quakers.Longfellow, pp. 5–95

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * , -External links

The Governor Bellingham~Cary House Association web site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bellingham, Richard 1592 births 1672 deaths Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford Colonial governors of Massachusetts Lieutenant Governors of colonial Massachusetts Politicians from Chelsea, Massachusetts Massachusetts lawyers English MPs 1628–1629 English lawyers 17th-century English lawyers 17th-century American people American Puritans 17th-century Protestants Burials at Granary Burying Ground Lawyers from Chelsea, Massachusetts