Revocation of the Edict of Nantes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an

The

The

By the Edict of Fontainebleau, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes and ordered the destruction of Huguenot churches as well as the closing of Protestant schools. The edict made official the policy of persecution that was already enforced since the ''

By the Edict of Fontainebleau, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes and ordered the destruction of Huguenot churches as well as the closing of Protestant schools. The edict made official the policy of persecution that was already enforced since the ''

online

* Dubois, E. T. "The revocation of the edict of Nantes — Three hundred years later 1685–1985." ''History of European Ideas '' 8#3 (1987): 361-365. reviews 9 new books

online

* Scoville, Warren Candler. ''The persecution of Huguenots and French economic development, 1680-1720'' (1960). * Scoville, Warren C. "The Huguenots in the French economy, 1650–1750." ''Quarterly Journal of Economics'' 67.3 (1953): 423-444.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edict Of Fontainebleau 1685 in France

edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Proc ...

issued by French King Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

(1598) had granted Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster B ...

the right to practice their religion without state persecution. Protestants had lost their independence in places of refuge under Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

on account of their supposed insubordination, but they continued to live in comparative security and political contentment. From the outset, religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

in France had been a royal, rather than popular, policy.

The lack of universal adherence to his religion did not sit well with Louis XIV's vision of perfected autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

.Palmer, ''eo. loc.''

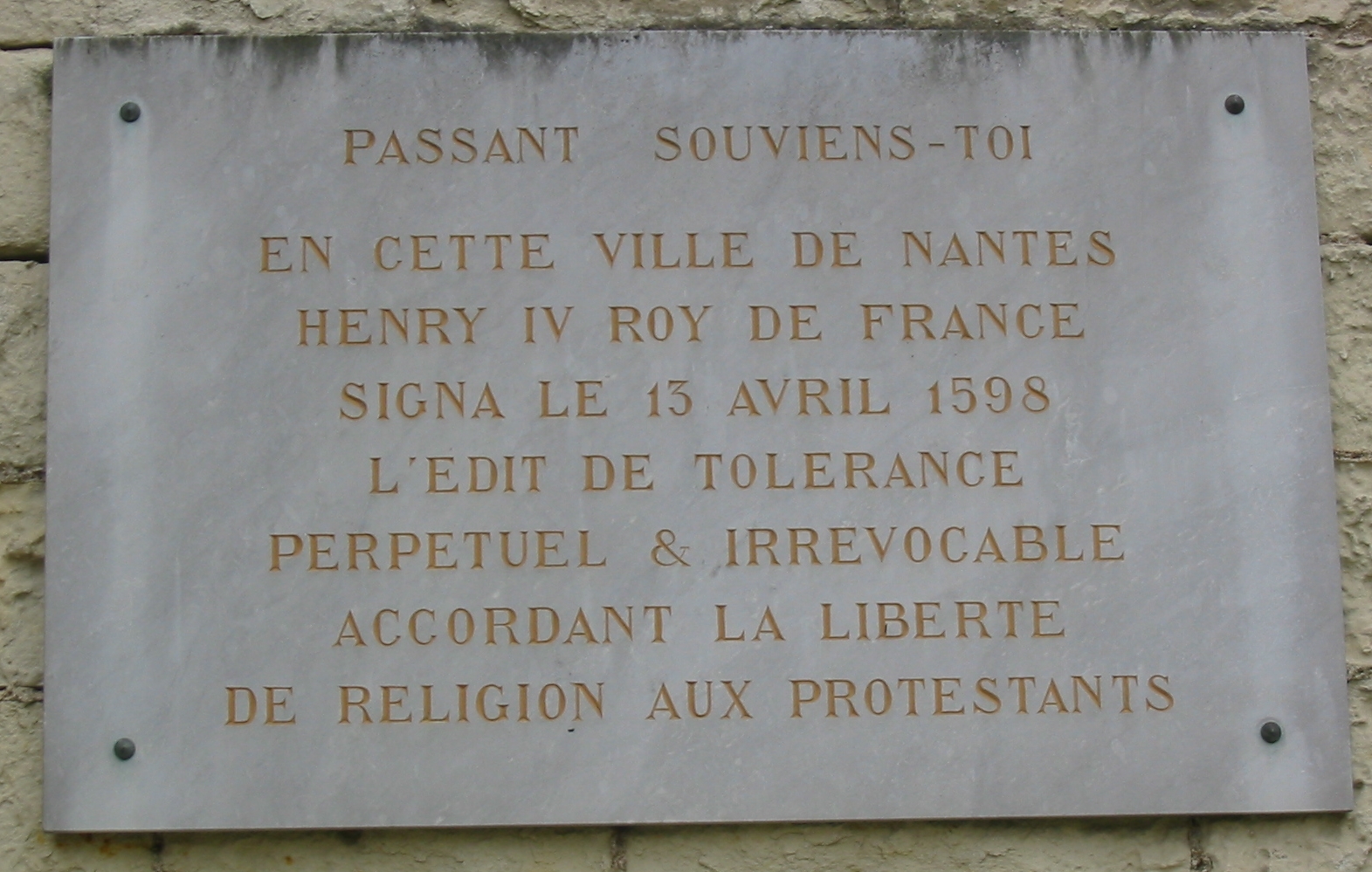

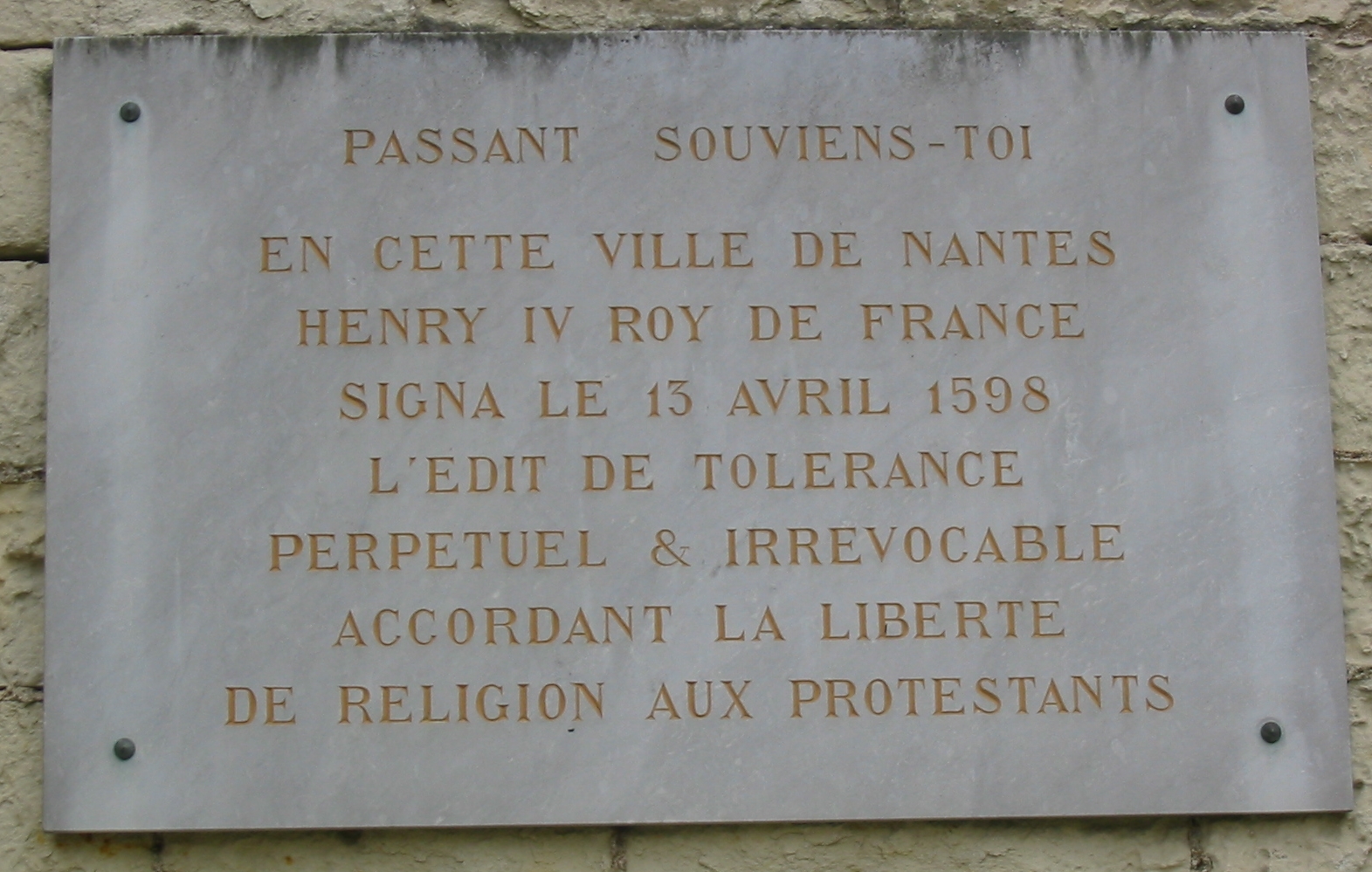

Edict of Nantes

The

The Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

had been issued on 13 April 1598 by Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monar ...

and granted the Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

Protestants

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, also known as Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster B ...

, substantial rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory ...

in the predominantly-Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

state. Henry aimed at promoting civil unity by the edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Proc ...

. The edict treated some Protestants with tolerance and opened a path for secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a si ...

. It offered general freedom of conscience

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency ...

to individuals and many specific concessions to the Protestants, such as amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

and the reinstatement of their civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

, including the rights to work in any field, including for the state, and to bring grievances directly to the king. It marked the end of the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mil ...

, which had afflicted France during the second half of the 16th century.

Revocation

By the Edict of Fontainebleau, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes and ordered the destruction of Huguenot churches as well as the closing of Protestant schools. The edict made official the policy of persecution that was already enforced since the ''

By the Edict of Fontainebleau, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes and ordered the destruction of Huguenot churches as well as the closing of Protestant schools. The edict made official the policy of persecution that was already enforced since the ''dragonnades

The ''Dragonnades'' were a French government policy instituted by King Louis XIV in 1681 to intimidate Huguenot (Protestant) families into converting to Catholicism. This involved the billeting of ill-disciplined dragoons in Protestant household ...

'' that he had created in 1681 to intimidate Huguenots into converting to Catholicism. As a result of the officially-sanctioned persecution by the ''dragoons

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

'', who were billeted

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, alth ...

upon prominent Huguenots, many Protestants, estimates ranging from 210,000 to 900,000, left France over the next two decades. They sought asylum in the United Provinces, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, Protestant states of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

in Africa and North America. On 17 January 1686, Louis XIV claimed that out of a Huguenot population of 800,000 to 900,000, only 1,000 to 1,500 had remained in France.

It has long been said that a strong advocate for persecution of the Protestants was Louis XIV's pious second wife, Madame de Maintenon, who was thought to have urged Louis to revoke Henry IV's edict. There is no formal proof of that, and such views have now been challenged. Madame de Maintenon was by birth a Catholic but was also the grand-daughter of Agrippa d'Aubigné, an unrelenting Calvinist. Protestants tried to turn Madame de Maintenon and any time she took the defence of Protestants, she was suspected of relapsing into her family faith. Thus, her position was thin, which wrongly led people to believe that she advocated persecutions.

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes brought France into line with virtually every other European country of the period (with the exception of the Principality of Transylvania and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

), which legally tolerated only the majority state religion. The French experiment of religious tolerance in Europe was effectively ended for the time being.

Effects

The Edict of Fontainebleau is compared by many historians with the 1492Alhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492, by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Arag ...

ordering the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and the Expulsion of the Moriscos

The Expulsion of the Moriscos ( es, Expulsión de los moriscos) was decreed by King Philip III of Spain on April 9, 1609. The Moriscos were descendants of Spain's Muslim population who had been forced to convert to Christianity. Since the Spani ...

in 1609 to 1614. All three are similar both as outbursts of religious intolerance ending periods of relative tolerance and in their social and economic effects. In practice, the revocation caused France to suffer a kind of early brain drain, as it lost many skilled craftsmen, including key designers such as Daniel Marot. Upon leaving France, Huguenots took with them knowledge of important techniques and styles, which had a significant effect on the quality of the silk, plate glass, silversmithing

A silversmith is a metalworker who crafts objects from silver. The terms ''silversmith'' and '' goldsmith'' are not exactly synonyms as the techniques, training, history, and guilds are or were largely the same but the end product may vary g ...

, watchmaking and cabinet making industries of those regions to which they relocated. Some rulers, such as Frederick Wilhelm, Duke of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg, who issued the Edict of Potsdam in late October 1685, encouraged the Protestants to seek refuge in their nations. Similarly, in 1720 Frederick IV of Denmark

Frederick IV ( Danish: ''Frederik''; 11 October 1671 – 12 October 1730) was King of Denmark and Norway from 1699 until his death. Frederick was the son of Christian V of Denmark-Norway and his wife Charlotte Amalie of Hesse-Kassel.

Early l ...

invited the French Huguenots to seek refuge in Denmark, which they accepted, settling in Fredericia and other locations.

Abolition

In practice, the stringency of policies outlawing Protestants was opposed by the Jansenists and was relaxed during the reign ofLouis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

, especially among discreet members of the upper classes. "The fact that a hundred years later, when Protestants were again tolerated, many of them were found to be both commercially prosperous and politically loyal indicates that they fared far better than the Catholic Irish", R.R. Palmer concluded.

By the late 18th century, numerous prominent French philosophers and literary men of the day, including Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de l'Aulne ( ; ; 10 May 172718 March 1781), commonly known as Turgot, was a French economist and statesman. Originally considered a physiocrat, he is today best remembered as an early advocate for economic libe ...

, were arguing strongly for religious tolerance. Efforts by Guillaume-Chrétien de Malesherbes, minister to Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

, and Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne

Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne (; 14 November 1743 – 5 December 1793) was a leader of the French Protestants and a moderate French revolutionary.

Biography

Jean-Paul Rabaut was born in 1743 in Nîmes, in the department of Gard, the son of Paul ...

, a spokesman for the Protestant community, together with members of a provincial appellate court or ''parlement

A ''parlement'' (), under the French Ancien Régime, was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 parlements, the oldest and most important of which was the Parlement of Paris. While both the modern Fr ...

'' of the Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

, were particularly effective in persuading the king to open French society despite concerns expressed by some of his advisors. Thus, on 7 November 1787, Louis XVI signed the Edict of Versailles

The Edict of Versailles, also known as the Edict of Tolerance, was an official act that gave non-Catholics in France the access to civil rights formerly denied to them, which included the right to contract marriages without having to convert to t ...

, known as the edict of tolerance registered in the ''parlement'' months later, on 29 January 1788. The edict offered relief to the main alternative faiths of Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster B ...

, Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

by giving their followers civil and legal recognition as well as the right to form congregations openly after 102 years of prohibition.

Full religious freedom had to wait two more years, with enactment of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1789

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolu ...

. The 1787 edict was a pivotal step in eliminating religious strife, however, and officially ended religious persecution in France. Moreover, when French revolutionary armies invaded other European countries between 1789 and 1815, they followed a consistent policy of emancipating persecuted or circumscribed religious communities (Roman Catholic in some countries, Protestant in others and Jewish in most).

Apology

In October 1985, in the tricentenary of the Edict of Fontainebleau, French PresidentFrançois Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

issued a public apology to the descendants of Huguenots around the world.

Famous Huguenots who left France

*Jean Barbot

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Je ...

* Jean Chardin

Jean Chardin (16 November 1643 – 5 January 1713), born Jean-Baptiste Chardin, and also known as Sir John Chardin, was a French jeweller and traveller whose ten-volume book ''The Travels of Sir John Chardin'' is regarded as one of the finest ...

* de la Font

* Jean Luzac (see also Nouvelles Extraordinaires de Divers Endroits

''Nouvelles Extraordinaires de Divers Endroits'' (English: "Extraordinary News from Various Places") or ''Gazette de Leyde'' (Gazette of Leiden) was the most important newspaper of record of the international European newspapers of the late 17th ...

)

* Daniel Marot

* Abraham de Moivre

Abraham de Moivre FRS (; 26 May 166727 November 1754) was a French mathematician known for de Moivre's formula, a formula that links complex numbers and trigonometry, and for his work on the normal distribution and probability theory.

He move ...

* Denis Papin

Denis Papin FRS (; 22 August 1647 – 26 August 1713) was a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the pressure cooker and of the steam engine.

Early li ...

* Duke of Schomberg

Duke of Schomberg in the Peerage of England was created in 1689. The title derives from the surname of its holder (originally Schönberg).

The Duke of Schomberg was part of King William of Orange's army and camped in the Holywood hills area of ...

See also

* War of the Camisards *French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mil ...

* Religions in France

* Edict of Potsdam

* 1731 Expulsion of Protestants from Salzburg

* Savoyard–Waldensian wars

* Brain Drain

* End of the persecution of Huguenots and restoration of French citizenship

* Right of return to France

References

Further reading

* Baird, Henry Martyn. ''The Huguenots and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes'' (1895)online

* Dubois, E. T. "The revocation of the edict of Nantes — Three hundred years later 1685–1985." ''History of European Ideas '' 8#3 (1987): 361-365. reviews 9 new books

online

* Scoville, Warren Candler. ''The persecution of Huguenots and French economic development, 1680-1720'' (1960). * Scoville, Warren C. "The Huguenots in the French economy, 1650–1750." ''Quarterly Journal of Economics'' 67.3 (1953): 423-444.

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edict Of Fontainebleau 1685 in France

Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau (; ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissemen ...

Religion in the Ancien Régime

Huguenot history in France

Louis XIV

Christianity and law in the 17th century

Religion and politics

Persecution of the Huguenots

1685 in religion

Religious expulsion orders