Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a

country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, while ...

in

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

, at the junction of the

East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

and

South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phi ...

s in the northwestern

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

, with the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

(PRC) to the northwest,

Japan to the northeast, and the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

to the south. The

territories controlled by the ROC consist of

168 islands, with a combined area of .

The main

island of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is an island country located in East Asia. The main island of Taiwan, formerly known in the Western political circles, press and literature as Formosa, makes up 99% of the land area of the territori ...

, also known as ''Formosa'', has an area of , with mountain ranges dominating the eastern two-thirds and plains in the western third, where its

highly urbanised population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using a ...

is concentrated. The capital,

Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

, forms along with

New Taipei City

New Taipei City is a special municipality located in northern Taiwan. The city is home to an estimated population of 3,974,683 as of 2022, making it the most populous city of Taiwan, and also the second largest special municipality by area, b ...

and

Keelung the

largest metropolitan area of Taiwan. Other major cities include

Taoyuan,

Taichung

Taichung (, Wade–Giles: ''Tʻai²-chung¹'', pinyin: ''Táizhōng''), officially Taichung City, is a special municipality located in central Taiwan. Taichung has approximately 2.8 million residents and is the second most populous city of Ta ...

,

Tainan

Tainan (), officially Tainan City, is a special municipality in southern Taiwan facing the Taiwan Strait on its western coast. Tainan is the oldest city on the island and also commonly known as the "Capital City" for its over 200 years of his ...

, and

Kaohsiung. With around 23.9 million inhabitants, Taiwan is among the

most densely populated countries in the world.

Taiwan has been settled for at least 25,000 years. Ancestors of

Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Taiwanese indigenous peoples (formerly Taiwanese aborigines), also known as Formosan people, Austronesian Taiwanese, Yuanzhumin or Gaoshan people, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 5 ...

settled the

island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

around 6,000 years ago. In the 17th century, large-scale

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctiv ...

(specifically the

Hakkas

The Hakka (), sometimes also referred to as Hakka Han, or Hakka Chinese, or Hakkas are a Han Chinese subgroup whose ancestral homes are chiefly in the Hakka-speaking provincial areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan ...

and

Hoklos

The Hoklo people or Hokkien people () are a Han Chinese (also Han Taiwanese) subgroup who speak Hokkien, a Southern Min language, or trace their ancestry to Southeastern Fujian, China and known by various endonyms or other related terms such a ...

) immigration to western Taiwan began under a

Dutch colony and continued under the

Kingdom of Tungning

The Kingdom of Tungning (), also known as Tywan by the British at the time, was a dynastic maritime state that ruled part of southwestern Taiwan and the Penghu islands between 1661 and 1683. It is the first predominantly Han Chinese state in ...

. The island was

annexed in 1683 by the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

of China and

ceded to the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

in 1895. The

Republic of China, which had

overthrown the Qing in 1911, took control of Taiwan on behalf of the

Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

following the

surrender of Japan in 1945. The immediate resumption of the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

resulted in the loss of the

Chinese mainland

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

to

Communist forces who

established the People's Republic of China, and

the flight of the ROC central government to Taiwan in 1949. The effective jurisdiction of the ROC has since been limited to

Formosa, Penghu, and smaller islands.

In the early 1960s, Taiwan entered a period of rapid economic growth and industrialisation called the "

Taiwan Miracle

The Taiwan Miracle () or Taiwan Economic Miracle refers to the rapid industrialization and economic growth of Taiwan during the latter half of the twentieth century.

As it developed alongside Singapore, South Korea and Hong Kong, Taiwan became ...

". In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the ROC transitioned from a

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

under

martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

to a

multi-party democracy

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in coal ...

, with democratically elected presidents

since 1996. Taiwan's

export-oriented industrial economy is the

21st-largest in the world by nominal GDP and

19th-largest by PPP measures, with a focus on steel, machinery, electronics and chemicals manufacturing. Taiwan is a

developed country,

[World Bank Country and Lending Groups](_blank)

, World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Inte ...

. Retrieved 10 July 2018. ranking 20th on

GDP per capita. It is ranked highly in terms of

civil liberties,

healthcare, and

human development Human development may refer to:

* Development of the human body

* Developmental psychology

* Human development (economics)

* Human Development Index, an index used to rank countries by level of human development

* Human evolution

Human evoluti ...

.

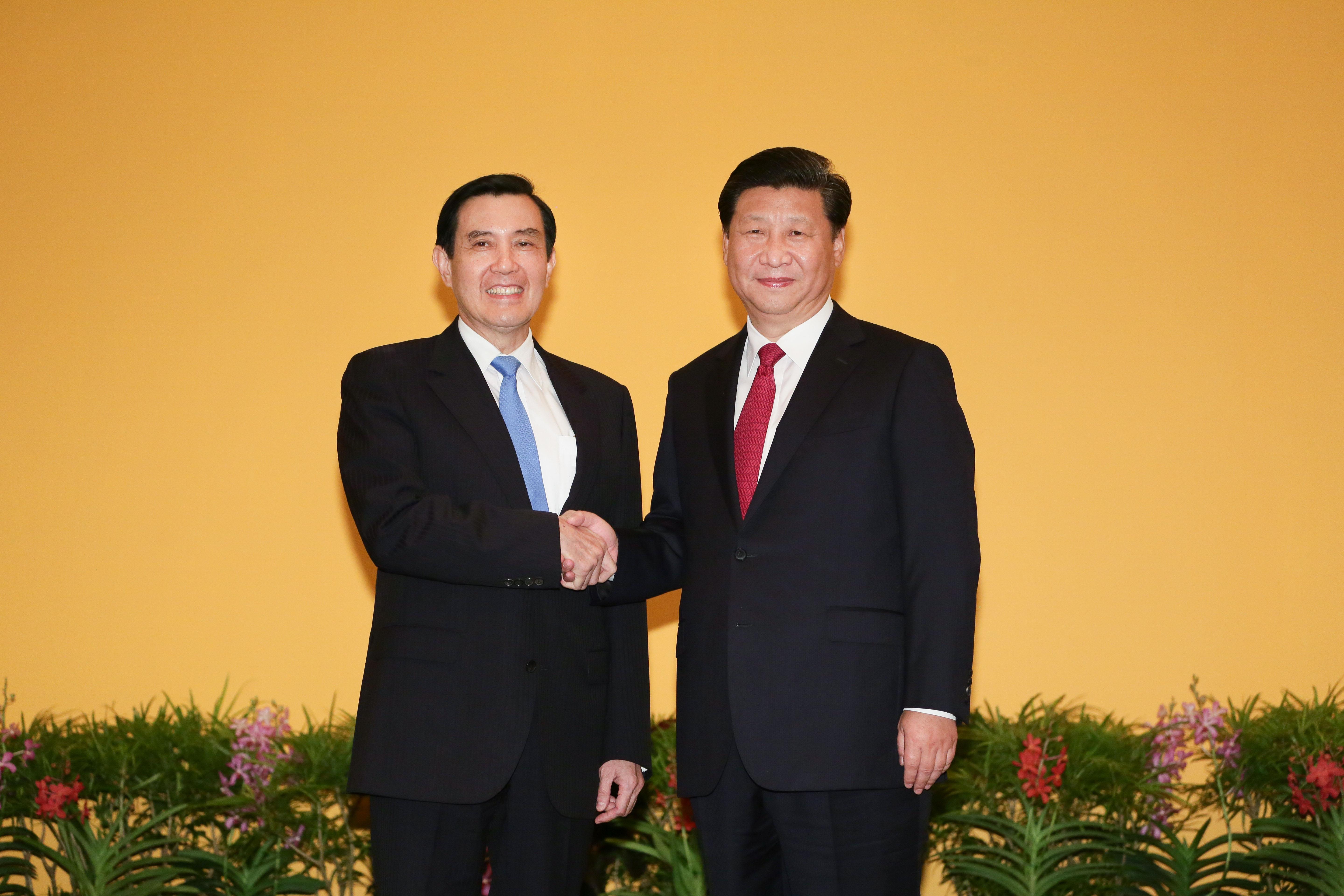

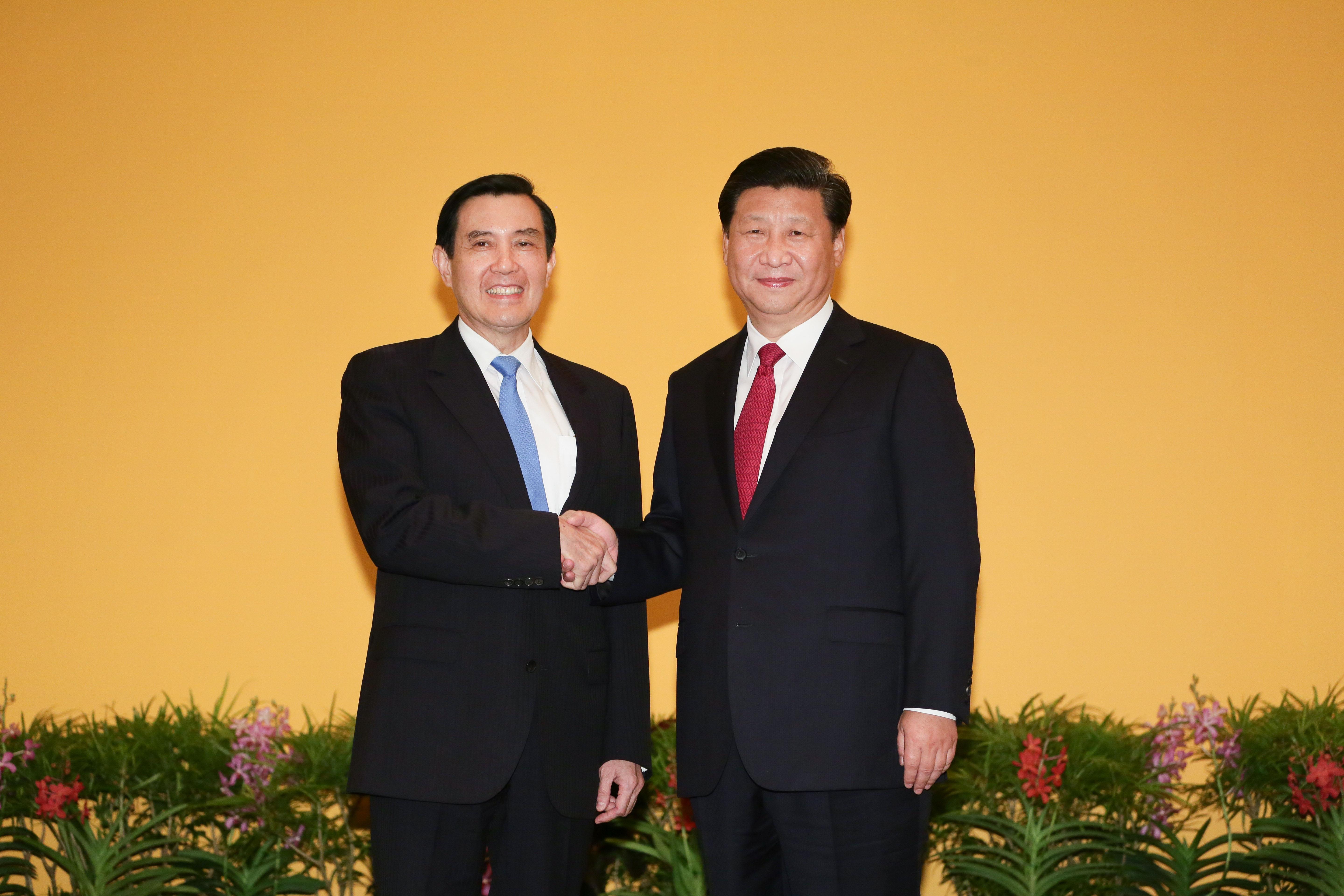

The

political status of Taiwan is contentious. The ROC no longer represents China as a member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, after UN members voted in 1971 to

recognize the PRC instead.

The ROC maintained its claim of being the sole

legitimate representative of China and its territory, although this has been downplayed since its

democratization in the 1990s. Taiwan is claimed by the PRC, which refuses diplomatic relations with countries that recognise the ROC. Taiwan

maintains official diplomatic relations with 13 out of 193 UN member states and the

Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

,

though many others maintain unofficial diplomatic ties through

representative offices and institutions that function as

''de facto'' embassies and consulates. International organisations in which the PRC participates either refuse to grant membership to Taiwan or allow it to participate only on a non-state basis under various names. Domestically, the major political contention is between parties favouring eventual

Chinese unification and promoting a pan-Chinese identity, contrasted with those

aspiring to formal international recognition and promoting a

Taiwanese identity

Taiwanese people may be generally considered the people of Taiwan who share a common culture, ancestry and speak Taiwanese Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka or indigenous Taiwanese languages as a mother tongue. Taiwanese people may also refer to the i ...

; into the 21st century, both sides have moderated their positions to broaden their appeal.

Etymology

Name of the island

Various names for the island of Taiwan remain in use, each derived from explorers or rulers during a particular historical period.

In his ''

Daoyi Zhilüe

''Daoyi Zhilüe'' () or ''Daoyi Zhi'' () which may be translated as ''A Brief Account of Island Barbarians'' or other similar titles, is a book written c. 1339 (completed c. 1349) by Yuan Dynasty Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan recounting his trave ...

'' (1349),

Wang Dayuan Wang Dayuan (, fl. 1311–1350), courtesy name Huanzhang (), was a Chinese traveller of the Yuan dynasty from Quanzhou in the 14th century. He is known for his two major ship voyages.

Wang Dayuan was born around 1311 at Hongzhou (present-day Nan ...

used "

Liuqiu" as a name for the island of Taiwan, or the part of it closest to

Penghu. Elsewhere, the name was used for the

Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yona ...

in general or

Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

, the largest of the islands; the name ''Ryūkyū'' is the Japanese form of ''Liúqiú''. The name also appears in the ''

Book of Sui

The ''Book of Sui'' (''Suí Shū'') is the official history of the Sui dynasty. It ranks among the official Twenty-Four Histories of imperial China. It was written by Yan Shigu, Kong Yingda, and Zhangsun Wuji, with Wei Zheng as the lead author. ...

'' (636) and other early works, but scholars cannot agree on whether these references are to the Ryukyus, Taiwan or even

Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, as ...

.

The name

Formosa () dates from 1542, when

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

sailors sighted an uncharted island and noted it on their maps as ''Ilha Formosa'' ("beautiful island").

The name ''Formosa'' eventually "replaced all others in European literature" and remained in common use among English speakers into the 20th century.

In the winter of 1602-1603, a Chinese expedition fleet anchored at a place in Taiwan called Dayuan, a variant of "Taiwan", and met with the native chieftain named Damila. In the early 17th century, the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

established a commercial post at

Fort Zeelandia (modern-day

Anping,

Tainan

Tainan (), officially Tainan City, is a special municipality in southern Taiwan facing the Taiwan Strait on its western coast. Tainan is the oldest city on the island and also commonly known as the "Capital City" for its over 200 years of his ...

) on a coastal sandbar called "Tayouan", after their

ethnonym for a nearby

Taiwanese aboriginal

Taiwanese indigenous peoples (formerly Taiwanese aborigines), also known as Formosan people, Austronesian Taiwanese, Yuanzhumin or Gaoshan people, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about ...

tribe, possibly

Taivoan people

The Taivoan (; ) or Tevorangh (; ) people or Shisha (), also written Taivuan and Tevorang, Tivorang, Tivorangh, are a Taiwanese indigenous people.

The Taivoan originally settled around hill and basin areas in Tainan, especially in the , which ar ...

, written by the Dutch and Portuguese variously as ''Taiouwang'', ''Tayowan'', ''Teijoan'', etc.

This name was also adopted into the Chinese vernacular (in particular,

Hokkien

The Hokkien () variety of Chinese is a Southern Min language native to and originating from the Minnan region, where it is widely spoken in the south-eastern part of Fujian in southeastern mainland China. It is one of the national languages ...

, as ) as the name of the sandbar and nearby area (Tainan). The modern word "Taiwan" is derived from this usage, which is written in different transliterations ( and ) in Chinese historical records. The area occupied by modern-day Tainan was the first permanent settlement by both European colonists and Chinese immigrants. The settlement grew to be the island's most important trading centre and served as its capital until 1887.

Use of the current Chinese name () became official as early as 1684 during the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

with the establishment of

Taiwan Prefecture

Taiwan Prefecture or Taiwanfu was a prefecture of Taiwan during the Qing dynasty. The prefecture was established by the Qing government in 1684, after the island came under Qing dynasty rule in 1683 following its conquest of the Kingdom of Tungnin ...

centered in modern-day Tainan. Through its rapid development the entire Taiwanese mainland eventually became known as "Taiwan".

Name of the country

The official name of the country in English is the "Republic of China"; it has also been known under various names throughout its existence. Shortly after the ROC's establishment in 1912, while it was still located on the Chinese mainland, the government used the short form "China" (' ()) to refer to itself, which derives from ' ("central" or "middle") and ' ("state, nation-state"), a term which also developed under the

Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by ...

in reference to its

royal demesne, and the name was then applied to the area around

Luoyi (present-day Luoyang) during the

Eastern Zhou

The Eastern Zhou (; zh, c=, p=Dōngzhōu, w=Tung1-chou1, t= ; 771–256 BC) was a royal dynasty of China and the second half of the Zhou dynasty. It was divided into two periods: the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States.

History

In 770 ...

and then to China's

Central Plain before being used as an occasional synonym for the state during the

Qing era.

The name of the Republic had stemmed from the party manifesto of

Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

in 1905, which says the four goals of the Chinese revolution was "to expel the

Manchu rulers, to revive

''Chunghwa'', to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people.()." The convener of Tongmenghui and Chinese revolutionary leader

Sun Yat-sen proposed the name ''Chunghwa Minkuo'' as the assumed name of the new country when the revolution succeeded.

During the 1950s and 1960s, after the ROC government had withdrawn to Taiwan upon losing the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

, it was commonly referred to as "Nationalist China" (or "

Free China") to differentiate it from "Communist China" (or "

Red China"). It was a member of the United Nations representing China until 1971, when the ROC

lost its seat to the People's Republic of China. Over subsequent decades, the Republic of China has become commonly known as "Taiwan", after the main island. In some contexts, including ROC government publications, the name is written as "Republic of China (Taiwan)", "Republic of China/Taiwan", or sometimes "Taiwan (ROC)".

The Republic of China participates in most international forums and organizations under the name "

Chinese Taipei" as a compromise with the People's Republic of China (PRC). For instance, it is the name under which it has participated in the

Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a vari ...

as well as the

World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and ...

. In 2009, after reaching an agreement with Beijing, the ROC participated in the

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

for the first time in 38 years, under the name "Chinese Taipei".

"Taiwan authorities" is sometimes used by the PRC to refer to the current government in Taiwan.

History

Early settlement (to 1683)

Taiwan was joined to the Asian mainland in the

Late Pleistocene, until sea levels rose about 10,000 years ago.

Fragmentary human remains dated 20,000 to 30,000 years ago have been found on the island, as well as later artifacts of a

Paleolithic culture.

These people were similar to the

negrito

The term Negrito () refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations often described as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples (including the Great Andamanese, the O ...

s of the Philippines.

Around 6,000 years ago, Taiwan was settled by farmers, most likely from what is now southeast China.

They are believed to be the ancestors of today's Taiwanese indigenous peoples, whose languages belong to the

Austronesian language family, but show much greater diversity than the

rest of the family, which spans a huge area from

Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

west to

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

and east as far as New Zealand, Hawaii and

Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its ne ...

. This has led linguists to propose Taiwan as the

urheimat

In historical linguistics, the homeland or ''Urheimat'' (, from German '' ur-'' "original" and ''Heimat'', home) of a proto-language is the region in which it was spoken before splitting into different daughter languages. A proto-language is the r ...

of the family, from which seafaring peoples dispersed across Southeast Asia and the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Trade links with the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

subsisted from the early 2nd millennium BC, including the use of

jade from eastern Taiwan in the

Philippine jade culture. The raw jade from Taiwan which was further processed in the Philippines was the basis for Taiwanese-Philippine commerce with ancient

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

,

Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

,

Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely surrounded by t ...

,

Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

,

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

,

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, and

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

.

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctiv ...

fishermen had settled on the Penghu Islands by 1171, when a group of "Bisheye" bandits with dark skin speaking a foreign language, a Taiwanese people related to the Bisaya of the

Visayas

The Visayas ( ), or the Visayan Islands (Visayan: ''Kabisay-an'', ; tl, Kabisayaan ), are one of the three principal geographical divisions of the Philippines, along with Luzon and Mindanao. Located in the central part of the archipelago, ...

, Philippines had landed on Penghu and plundered the fields planted by Chinese migrants. The

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

sent soldiers after them and from that time on, Song patrols regularly visited Penghu in the spring and summer. A local official, Wang Dayou, had houses built on Penghu and stationed troops there to prevent depredations from the Bisheye. In 1225, the ''

Book of Barbarian Nations'' anecdotally indicated that Penghu was attached to

Jinjiang,

Quanzhou Prefecture.

A group of Quanzhou immigrants lived on Penghu. In November 1281, the

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

under

Emperor Shizu officially established the ''

Penghu Patrol and Inspection Agency'' under the jurisdiction of

Tong'an

Tong'an District () is a northern mainland district of Amoy which faces Quemoy County, Republic of China. To the north is Anxi and Nan'an, and to the south is Jimei. Tong'an is also east of Lianxiang and Changqin to the West. It covers County, incorporating Penghu into China's sovereign domain, 403 years earlier than Taiwan island.

Hostile tribes, and a lack of valuable trade products, meant that few outsiders visited the main island until the 16th century.

[ Reprinted Taipei: SMC Publishing, 1995.] During the 16th century, visits to the coast by fishermen and traders from Fujian, as well as Chinese and Japanese pirates, became more frequent.

In the 15th century, the

Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

ordered the evacuation of the Penghu Islands as part of their

maritime ban. When these restrictions were removed in the late 16th century, legal fishing communities, most of which hailing from

Tong'an

Tong'an District () is a northern mainland district of Amoy which faces Quemoy County, Republic of China. To the north is Anxi and Nan'an, and to the south is Jimei. Tong'an is also east of Lianxiang and Changqin to the West. It covers County,

[「明萬曆年以後,澎湖第二次有移住民,以福建泉州府屬同安縣金門人遷來最早; 其後接踵而至者,亦以同安縣人為最多。彼等捷足先至者,得以優先選擇良好地區定居之,澎湖本島即多被同安人所先占; 尤其素稱土地沃之湖西鄉,完全成為同安人之區域。](_blank)

李紹章《澎湖縣誌》,《續修澎湖縣志(卷三)|人民志》 were re-established on the Penghu Islands. The

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

(the VOC) attempted to establish a trading outpost on the Penghu Islands (Pescadores) in 1622, but was

driven off by Ming forces.

In 1624, the VOC established a stronghold called Fort Zeelandia on the coastal islet of Tayouan, which is now part of the main island at

Anping, Tainan

Anping District is a district of Tainan, Taiwan. In March 2012, it was named one of the ''Top 10 Small Tourist Towns'' by the Tourism Bureau of Taiwan. It is home to 67,263 people.

Name

The older place name of Tayouan derives from the ...

.

When the Dutch arrived, they found southwestern Taiwan already frequented by a mostly transient Chinese population numbering close to 1,500. David Wright, a Scottish agent of the VOC who lived on the island in the 1650s, described the lowland areas of the island as being divided among 11

chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

s ranging in size from two settlements to 72. Some of these fell under Dutch control, including the

Kingdom of Middag in the central western plains, while others remained independent.

The VOC encouraged farmers to immigrate from

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

and work the lands under Dutch control. By the 1660s, some 30,000 to 50,000 Chinese were living on the island. Most of the farmers cultivated rice for local consumption and sugar for export. Some immigrants were engaged in commercial deer hunting. Deerskins were sold to the Dutch and exported to Japan. Venison, horns and genitals were exported to China where the products were used as food or medicine.

In 1626, the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

landed on and occupied northern Taiwan as a trading base, first at

Keelung and in 1628 building

Fort San Domingo at

Tamsui

Tamsui District (Hokkien POJ: ''Tām-chúi''; Hokkien Tâi-lô: ''Tām-tsuí''; Mandarin Pinyin: ''Dànshuǐ'') is a seaside district in New Taipei, Taiwan. It is named after the Tamsui River; the name means "fresh water". The town is popul ...

. This colony lasted 16 years until 1642, when the last Spanish fortress fell to Dutch forces. The Dutch then marched south, subduing hundreds of villages in the western plains between their new possessions in the north and their base at Tayouan.

Following the fall of the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

in Beijing in 1644,

Koxinga

Zheng Chenggong, Prince of Yanping (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), better known internationally as Koxinga (), was a Ming loyalist general who resisted the Qing conquest of China in the 17th century, fighting them on China's southeastern ...

(Zheng Chenggong) pledged allegiance to the

Yongli Emperor

The Yongli Emperor (; 1623–1662; reigned 18 November 1646 – 1 June 1662), personal name Zhu Youlang, was a royal member to the imperial family of Ming dynasty, and the fourth and last commonly recognised emperor of the Southern Ming, reigni ...

of

Southern Ming

The Southern Ming (), also known as the Later Ming (), officially the Great Ming (), was an imperial dynasty of China and a series of rump states of the Ming dynasty that came into existence following the Jiashen Incident of 1644. Shun force ...

and attacked the Qing dynasty along the southeastern coast of China.

[.] In 1661, under increasing Qing pressure, he moved his forces from his base in

Xiamen

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong'an ...

to Taiwan,

expelling the Dutch in the following year. After being ousted from Taiwan, the Dutch allied with the new Qing dynasty in China against the Zheng regime in Taiwan. Following some skirmishes the Dutch retook the northern fortress at

Keelung in 1664.

Zheng Jing sent troops to dislodge the Dutch, but they were unsuccessful. The Dutch held out at Keelung until 1668, when aborigine resistance, and the lack of progress in retaking any other parts of the island persuaded the colonial authorities to abandon this final stronghold and withdraw from Taiwan altogether.

The Zheng regime, known as

Kingdom of Tungning

The Kingdom of Tungning (), also known as Tywan by the British at the time, was a dynastic maritime state that ruled part of southwestern Taiwan and the Penghu islands between 1661 and 1683. It is the first predominantly Han Chinese state in ...

, is considered to be loyal to the Ming, while others argue that the regime acted as an independent ruler.

However, Zheng Jing's return to China to participate in the

Revolt of the Three Feudatories

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories, () also known as the Rebellion of Wu Sangui, was a rebellion in China lasting from 1673 to 1681, during the early reign of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). The revolt was ...

, a rebellion against the Qing court, ruined the regime and paved the way for the Qing invasion and occupation of Taiwan in 1683.

Qing rule (1683–1895)

Following the defeat of

Koxinga

Zheng Chenggong, Prince of Yanping (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), better known internationally as Koxinga (), was a Ming loyalist general who resisted the Qing conquest of China in the 17th century, fighting them on China's southeastern ...

's grandson by an armada led by Admiral

Shi Lang in 1683, the Qing dynasty formally annexed Taiwan in May 1684, making it a

prefecture of Fujian province while retaining its administrative seat (now Tainan) under Koxinga as the capital.

The Qing government generally tried to restrict migration to Taiwan throughout the duration of its administration because it believed that Taiwan could not sustain too large a population without leading to conflict. After the defeat of the Kingdom of Tungning, most of its population in Taiwan was sent back to the mainland, leaving the official population count at only 50,000: 546 inhabitants in Penghu, 30,229 in Taiwan, 8,108 aborigines, and 10,000 troops. Despite official restrictions, officials in Taiwan solicited settlers from the mainland, causing tens of thousands of annual arrivals from Fujian and Guangdong by 1711. A permit system was officially recorded in 1712 but it likely existed as early as 1684. Restrictions related to the permit system included only allowing those who had property on the mainland, family in Taiwan, and those who were not accompanied by wives or children, to enter Taiwan. Many of the male migrants married local indigenous women. Over the 18th century, restrictions on entering Taiwan were relaxed. In 1732, families were allowed to move to Taiwan, and in 1790, an office to manage cross-strait travel was established. By 1811 there were more than two million Han settlers in Taiwan and profitable sugar and rice production industries that provided exports to the mainland. In 1875, restrictions on entering Taiwan were repealed.

Three counties nominally covered the entire western plains, but actual control was restricted to a smaller area. A government permit was required for settlers to go beyond the

Dajia River

Dajia River () is the fifth-longest river in Taiwan located in the north-central of the island. It flows through Taichung City for 142 km.

The sources of the Dajia are: Hsuehshan and Nanhu Mountain in the Central Mountain Range. The Dajia R ...

at the mid-point of the western plains. Qing administration expanded across the western plains area over the 18th century, however this was not due to an active colonization policy, but a reflection of continued illegal crossings and settlement. The Taiwanese indigenous peoples were categorized by the Qing administration into acculturated aborigines who had adopted Han culture to some degree and non-acculturated aborigines who had not. The Qing did little to administer or subjugate them. When Taiwan was annexed, there were 46 aboriginal villages under its control, likely inherited from the Kingdom of Tungning. During the early

Qianlong

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his Temple name, temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, born Hongli, was the fifth List of emperors of the Qing dynasty, Emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing empe ...

period there were 93 acculturated villages and 61 non-acculturated villages that paid taxes. The number of acculturated villages remained unchanged throughout the 18th century. In response to the

Zhu Yigui

Zhu Yigui (; 1690–1722) was the leader of a Taiwanese uprising against Qing dynasty rule in mid-1721.

He came from a peasant family of Zhangzhou Hokkien ancestry and lived in the village of Lohanmen located in the area of modern-day Neimen Dist ...

uprising, a settler rebellion in 1722, separation of aboriginals and settlers became official policy via 54 stelae used to mark the frontier boundary. The markings were changed four times over the latter half of the 18th century due to continued settler encroachment. Two aboriginal affairs sub-prefects, one for the north and one for the south, were appointed in 1766.

During the 200 years of Qing rule in Taiwan, the plains aborigines rarely rebelled against the government and the mountain aborigines were left to their own devices until the last 20 years of Qing rule. Most of the rebellions, of which there were more than 100 during the Qing period, were caused by Han settlers.

More than a hundred rebellions, riots, and instances of civil strife occurred under the Qing administration, including the

Lin Shuangwen rebellion

The Lin Shuangwen rebellion () occurred in 17871788 in Taiwan under the rule of the Qing dynasty. The rebellion was started by the rebel Lin Shuangwen and was pacified by the Qianlong Emperor. Lin Shuangwen was then executed.

It started when the ...

(1786–1788). Their frequency was evoked by the common saying "every three years an uprising, every five years a rebellion" (三年一反、五年一亂), primarily in reference to the period between 1820 and 1850.

[.]

Many officials stationed in Taiwan called for an active colonization policy over the 19th century. In 1788, Taiwan Prefect Yang Tingli supported the efforts of a settler named Wu Sha in his attempt to claim land held by the

Kavalan people in modern

Yilan County. In 1797, Wu Sha was able to recruit settlers with financial support from the local government but was unable to officially register the land. In the early 1800s, local officials convinced the emperor to officially incorporate the area by playing up the issue of piracy if the land was left alone. In 1814, some settlers attempted to colonize central Taiwan by fabricating rights to lease aboriginal land. They were evicted by government troops two years later. Local officials continued to advocate for the colonization of the area but were ignored.

The Qing took on a more active colonization policy after 1874 when Japan

invaded aboriginal territory in southern Taiwan and the Qing government was forced to pay an indemnity for them to leave. The administration of Taiwan was expanded with new prefectures, sub-prefectures, and counties. Mountain roads were constructed to make inner Taiwan more accessible. Restrictions on entering Taiwan were ended in 1875 and agencies for recruiting settlers were established on the mainland, but efforts to promote settlement ended soon after. In 1884,

Keelung in northern Taiwan was occupied during the

Sino-French War but the French forces failed to advance any further inland while their victory at Penghu in 1885 resulted in disease and retreat soon afterward as the war ended. Colonization efforts were renewed under

Liu Mingchuan

Liu Ming-chuan (1836–1896), courtesy name Xingsan, lived in the late Qing dynasty. He was born in Hefei, Anhui. Liu became involved in the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion at an early age, and worked closely with Zeng Guofan and Li Ho ...

. In 1887, Taiwan's status was upgraded to a

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

.

Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

became a temporary capital and then the permanent capital in 1893. Liu's efforts to increase revenues on Taiwan's produce were hampered by foreign pressure not to increase levies. A land reform was implemented, increasing revenue which still fell short of expectation. Modern technologies such as electric lighting, a railway, telegraph lines, steamship service, and industrial machinery were introduced under Liu's governance, but several of these projects had mixed results. The telegraph line did not function at all times due to a difficult overland connection and the railway required an overhaul while servicing only small rolling stock with little freight load. A campaign to formally subjugate the aborigines was launched with 17,500 soldiers but ended with the loss of a third of the army after fierce resistance from the Mkgogan and Msbtunux peoples. Liu resigned in 1891 due to criticism of these costly projects.

By the end of the Qing period, the western plains were fully developed as farmland with about 2.5 million Chinese settlers. The mountainous areas were still largely autonomous under the control of aborigines. Aboriginal land loss under the Qing occurred at a relatively slow pace due to the absence of state sponsored land deprivation for the majority of Qing rule. Qing rule ended after the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

when it ceded Taiwan and the Penghu islands to Japan on 17 April 1895, according to the terms of the

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

.

Japanese rule (1895–1945)

Following the Qing defeat in the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

(1894–1895), Taiwan, its associated islands, and the Penghu archipelago were ceded to the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

by the

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

, along with other concessions.

[.] Inhabitants on Taiwan and Penghu wishing to remain Qing subjects and not to become Japanese had to move to mainland China within a two-year grace period. Very few Formosans saw this as feasible. Estimates say around four to six thousand departed before the expiration of the grace period, and two to three hundred thousand followed during the subsequent disorder. On 25 May 1895, a group of pro-Qing high officials proclaimed the

Republic of Formosa to resist impending Japanese rule. Japanese forces entered the capital at Tainan and quelled this resistance on 21 October 1895. About 6,000 inhabitants died in the initial fighting and some 14,000 died in the first year of Japanese rule. Another 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed from 1898 to 1902.

Several subsequent rebellions against the Japanese (the

Beipu uprising

The Beipu Incident (), or the Beipu Uprising, in 1907 was the first instance of an armed local uprising against the Japanese rule of the island of Taiwan. In response to oppression of the local population by the Japanese authorities, a group o ...

of 1907, the

Tapani incident

The Tapani incident or Tapani uprising in 1915 was one of the biggest armed uprisings by Taiwanese Han and Aboriginals, including Taivoan, against Japanese rule in Taiwan. Alternative names used to refer to the incident include the Xilai Temp ...

of 1915, and the

Musha incident of 1930) were all unsuccessful but demonstrated opposition to Japanese colonial rule.

The colonial period was instrumental to the industrialization of the island, with its expansion of railways and other transport networks, the building of an extensive sanitation system, the establishment of a formal

education system

The educational system generally refers to the structure of all institutions and the opportunities for obtaining education within a country. It includes all pre-school institutions, starting from family education, and/or early childhood education ...

, and an end to the practice of

headhunting

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and collecting the severed head after killing the victim, although sometimes more portable body parts (such as ear, nose or scalp) are taken instead as trophies. Headhunting was practiced in h ...

. During this period, the human and natural resources of Taiwan were used to aid the development of Japan. The production of

cash crops

A cash crop or profit crop is an agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") in subsiste ...

such as sugar greatly increased, especially since sugar cane was salable only to a few Japanese sugar mills, and large areas were therefore diverted from the production of rice, which the Formosans could market or consume themselves. By 1939, Taiwan was the seventh-greatest sugar producer in the world.

The Han and aboriginal populations were classified as second- and third-class citizens. Many prestigious government and business positions were closed to them, leaving few natives capable of taking on leadership and management roles decades later when Japan relinquished the island. After suppressing Han guerrillas in the first decade of their rule, Japanese authorities engaged in a series of bloody campaigns against the indigenous people residing in mountainous regions, culminating in the Musha Incident of 1930. Intellectuals and labourers who participated in left-wing movements within Taiwan were also arrested and massacred (e.g.

Chiang Wei-shui and

Masanosuke Watanabe). Around 1935, the Japanese began an island-wide

assimilation project to bind the island more firmly to the Japanese Empire.

Han culture was to be removed, and Chinese-language newspapers and curriculums were abolished. Taiwanese music and theater were outlawed. A national

Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

religion (國家神道) was promoted in parallel with the suppression of traditional Taiwanese beliefs through the reorganization of their temples and ancestral halls. Starting from 1940, families were also required to adopt

Japanese surname

Officially, among Japanese names there are 291,129 different Japanese surnames, as determined by their kanji, although many of these are pronounced and romanized similarly. Conversely, some surnames written the same in kanji may also be pronounced ...

s, although only 2% had done so by 1943.

By 1938, 309,000

Japanese settlers were residing in Taiwan.

Burdened by Japan's upcoming war effort, the island was developed into a naval and air base while its agriculture, industry, and commerce suffered. Initial air attacks and the subsequent invasion of the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

were launched from Taiwan. The

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

operated heavily from Taiwanese ports, and its think tank "

South Strike Group" was based at the

Taihoku Imperial University in Taipei. Military bases and industrial centres, such as

Kaohsiung and

Keelung, became targets of heavy

Allied bombings, which also destroyed many of the factories, dams, and transport facilities built by the Japanese. In October 1944, the

Formosa Air Battle

The Formosa Air Battle ( ja, 台湾沖航空戦, translation=Battle of the Taiwan Sea, ), 12–16 October 1944, was a series of large-scale aerial engagements between carrier air groups of the United States Navy Fast Carrier Task Force (TF38) an ...

was fought between American carriers and Japanese forces in Taiwan.

During the course of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, tens of thousands of Taiwanese served in the Japanese military. In 1944, Lee Teng-hui, who would become Taiwan's president later in life, volunteered for service in the

Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

and became a

second lieutenant. His elder brother, Lee Teng-chin (李登欽), also volunteered for the

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

and died in

Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

.

In addition, over 2,000 women, euphemistically called "

comfort women", were forced into sexual slavery for Imperial Japanese troops.

After

Japan's surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ( ...

in WWII, most of Taiwan's approximately 300,000 Japanese residents were

expelled and sent to Japan.

Republic of China (1945–present)

While Taiwan was still under Japanese rule, the Republic of China was founded on the mainland on 1 January 1912, following the

Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a ...

, which began with the

Wuchang uprising

The Wuchang Uprising was an armed rebellion against the ruling Qing dynasty that took place in Wuchang (now Wuchang District of Wuhan), Hubei, China on 10 October 1911, beginning the Xinhai Revolution that successfully overthrew China's last ...

on 10 October 1911, replacing the Qing dynasty and ending over two thousand years of

imperial rule in China.

From its founding until 1949 it was based in mainland China. Central authority waxed and waned in response to

warlordism

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

(1915–28),

Japanese invasion (1937–45), and the Chinese Civil War (1927–50), with central authority strongest during the

Nanjing decade

The Nanjing decade (also Nanking decade, , or the Golden decade, ) is an informal name for the decade from 1927 (or 1928) to 1937 in the Republic of China. It began when Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek took Nanjing from Zhili clique ...

(1927–37), when most of China came under the control of the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

(KMT) under an

authoritarian one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

.

In September 1945 following

Japan's surrender in WWII, ROC forces, assisted by small American teams, prepared an amphibious lift into Taiwan to accept the surrender of the Japanese military forces there, under

General Order No. 1

General Order No. 1 ( Japanese:一般命令第一号) for the surrender of Japan was prepared by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff and approved by President Harry Truman on August 17, 1945.

It was issued by General Douglas MacArthur to the ...

, and take over the administration of Taiwan. On 25 October, General

Rikichi Andō, governor-general of Taiwan and commander-in-chief of all Japanese forces on the island, signed the receipt and handed it over to ROC General

Chen Yi Chen Yi may refer to:

* Xuanzang (602–664), born as Chen Yi, Chinese Buddhist monk in Tang Dynasty

* Chen Yi (Kuomintang)

Chen Yi (; courtesy names Gongxia (公俠) and later Gongqia (公洽), sobriquet Tuisu (退素); May 3, 1883 – June ...

to complete the official turnover. Chen proclaimed that day to be "

Taiwan Retrocession Day", but the Allies, having entrusted Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to Chinese administration and military occupation, nonetheless considered them to be under Japanese sovereignty until 1952 when the

Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

took effect. In the

1943 Cairo Declaration

The Cairo Declaration was the outcome of the Cairo Conference in Cairo, Egypt, on 27 November 1943. President Franklin Roosevelt of the United States, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of ...

, US, UK, and ROC representatives specified territories such as Formosa and the Pescadores to be restored by Japan to the Republic of China.

Its terms were later referred to in the

1945 Potsdam Declaration,

whose provisions Japan agreed to carry out in its

instrument of surrender.

Due to disagreements over which government (PRC or ROC) to invite, China did not attend the eventual signing of the Treaty of San Francisco, whereby Japan renounced all titles and claims to Formosa and the Pescadores without specifying to whom they were surrendered.

In 1952, Japan and the ROC signed the

Treaty of Taipei

The Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (), formally the Treaty of Peace between the Republic of China and Japan () and commonly known as the Treaty of Taipei (), was a peace treaty between Japan and the Republic of China (ROC) signed in Taipei, Taiwan o ...

, recognizing that all treaties concluded before 9 December 1941 between China and Japan have become null and void.

Interpretations of these documents and their legal implications give rise to the debate over the

sovereignty status of Taiwan.

While initially enthusiastic about the return of Chinese administration and the

Three Principles of the People, Formosans grew increasingly dissatisfied about being excluded from higher positions, the postponement of local elections even after the enactment of a

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

on the mainland, the smuggling of valuables off the island, the expropriation of businesses into government operated monopolies, and the

hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

of 1945–1949. The shooting of a civilian on 28 February 1947 triggered island-wide unrest, which was suppressed by Chen with military force in what is now called the

February 28 Incident. Mainstream estimates of the number killed range from 18,000 to 30,000. Many native leaders were killed, as well as students and some mainlanders. Chen was later relieved and replaced by

Wei Tao-ming, who made an effort to undo previous mismanagement by re-appointing a good proportion of islanders and re-privatizing businesses.

After the end of World War II, the Chinese Civil War resumed between the Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang), led by Generalissimo

Chiang Kai-shek, and the

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

(CCP), led by

CCP Chairman Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

. Throughout the months of 1949, a series of Chinese Communist offensives led to the capture of its capital

Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

on 23 April and the subsequent defeat of the Nationalist army on the mainland, and the Communists

founded the People's Republic of China on 1 October.

On 7 December 1949, after the loss of four capitals, Chiang

evacuated his Nationalist government to Taiwan and made Taipei the

temporary capital A temporary capital or a provisional capital is a city or town chosen by a government as an interim base of operations due to some difficulty in retaining or establishing control of a different metropolitan area. The most common circumstances leadin ...

of the ROC (also called the "wartime capital" by Chiang Kai-shek).

Some 2 million people, consisting mainly of soldiers, members of the ruling Kuomintang and intellectual and business elites, were evacuated from mainland China to Taiwan at that time, adding to the earlier population of approximately six million. These people came to be known in Taiwan as "

waisheng ren" (), residents who came to the island in the 1940s and 50s after Japan's surrender, as well as their descendants. In addition, the ROC government took to Taipei many national treasures and much of China's

gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

and foreign currency reserves.

After losing control of mainland China in 1949, the ROC retained control of Taiwan and Penghu (

Taiwan, ROC), parts of Fujian (

Fujian, ROC)—specifically Kinmen,

Wuqiu (now part of Kinmen) and the Matsu Islands and two major

islands in the South China Sea (within the

Dongsha/Pratas and

Nansha/Spratly island groups). These territories have remained under ROC governance until the present day. The ROC also briefly retained control of the entirety of

Hainan

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slightly l ...

(an island province), parts of

Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , Chinese postal romanization, also romanized as Chekiang) is an East China, eastern, coastal Provinces of China, province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable citie ...

(

Chekiang)—specifically the

Dachen Islands

The Dachen Islands, Tachen Islands or Tachens () are a group of islands off the coast of Taizhou, Zhejiang, China, in the East China Sea. They are administered by the Jiaojiang District of Taizhou. Before the First Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1955, ...

and

Yijiangshan Islands

The Yijiangshan Islands () are two small islands eight miles from the Dachen Islands, located off the coast of Taizhou, Zhejiang in the East China Sea.

During the First Taiwan Strait crisis the islands were captured in January 1955 by the People's ...

—and portions of

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

,

Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

,

Sinkiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

and

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the C ...

. The Communists

captured Hainan in 1950, captured the Dachen Islands and Yijiangshan Islands during the

First Taiwan Strait Crisis

The First Taiwan Strait Crisis (also the Formosa Crisis, the 1954–1955 Taiwan Strait Crisis, the Offshore Islands Crisis, the Quemoy-Matsu Crisis, and the 1955 Taiwan Strait Crisis) was a brief armed conflict between the Communist People's ...

in 1955 and defeated the

ROC revolts in Northwest China in 1958. ROC forces in Yunnan province entered Burma and Thailand in the 1950s and

were defeated by Communists in 1961. Ever since losing control of mainland China, the Kuomintang continued to claim sovereignty over 'all of China', which it defined to include mainland China (including Tibet), Taiwan (including Penghu),

Outer Mongolia, and

other minor territories.

Martial law era (1949–1987)

Martial law, declared on Taiwan in May 1949,

continued to be in effect after the central government relocated to Taiwan. It was also used as a way to suppress the political opposition and was not repealed until 38 years later in 1987.

During the

White Terror, as the period is known, 140,000 people were imprisoned or executed for being perceived as anti-KMT or pro-Communist. Many citizens were arrested, tortured, imprisoned and executed for their real or perceived link to the Chinese Communist Party. Since these people were mainly from the intellectual and social elite, an entire generation of political and social leaders was decimated.

Due to the eruption of the

Korean war

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, and in the context of the Cold War, US President

Harry S. Truman decided to intervene again and dispatched the

United States Seventh Fleet

The Seventh Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It is headquartered at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It is part of the United States Pacific Fleet. At present, it is the largest of ...

into the

Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself a ...

to prevent hostilities between Taiwan and mainland China.

Continuing fierce combat between both sides of the Chinese Civil War through the 1950s, and intervention by the United States notably resulted in legislation such as the

Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty

The Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty (SAMDT), formally Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States of America and the Republic of China, was a defense pact signed between the United States and the Republic of China (Taiwan) effective from ...

and the

Formosa Resolution of 1955. By virtue of these pacts, the KMT regime received substantial

foreign aid from the US between 1951 and 1965. In the

Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

and the

Treaty of Taipei

The Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (), formally the Treaty of Peace between the Republic of China and Japan () and commonly known as the Treaty of Taipei (), was a peace treaty between Japan and the Republic of China (ROC) signed in Taipei, Taiwan o ...

, which came into force respectively on 28 April 1952 and 5 August 1952, Japan formally renounced all right, claim and title to Taiwan and Penghu, and renounced all treaties signed with China before 1942. Neither treaty specified to whom sovereignty over the islands should be transferred, because the United States and the United Kingdom disagreed on whether the ROC or the PRC was the legitimate government of China.

As the Chinese Civil War continued without truce, the government built up military fortifications throughout Taiwan. Within this effort, KMT veterans built the now famous

Central Cross-Island Highway

The Central Cross-Island Highway () or Provincial Highway 8 is one of three highway systems that connect the west coast with the east of Taiwan.

Construction

The construction of the Central Cross-Island Highway began on July 7, 1956 and wa ...

through the

Taroko Gorge in the 1950s. The two sides would continue to engage in sporadic military clashes with seldom publicized details well into the 1960s on the China coastal islands with an unknown number of

night raids. During the

Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, also called the 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis, was a conflict that took place between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC). In this conflict, the PRC shelled the islands of Kinm ...

in September 1958, Taiwan's landscape saw

Nike-Hercules missile

The Nike Hercules, initially designated SAM-A-25 and later MIM-14, was a surface-to-air missile (SAM) used by U.S. and NATO armed forces for medium- and high-altitude long-range air defense. It was normally armed with the W31 nuclear warhead, but ...

batteries added, with the formation of the 1st Missile Battalion Chinese Army that would not be deactivated until 1997. Newer generations of missile batteries have since replaced the Nike Hercules systems throughout the island.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the ROC maintained an authoritarian, single-party government under the Kuomintang's

Dang Guo

''Dang Guo'' ( zh, t=黨國, p=Dǎngguó, l=party-state) was the one-party system adopted by the Republic of China under the Kuomintang. It was from 1924 onwards, after Sun Yat-sen acknowledged the efficacy of the nascent Soviet Union's politi ...

system while its economy became industrialized and technology-oriented.

This rapid economic growth, known as the

Taiwan Miracle

The Taiwan Miracle () or Taiwan Economic Miracle refers to the rapid industrialization and economic growth of Taiwan during the latter half of the twentieth century.

As it developed alongside Singapore, South Korea and Hong Kong, Taiwan became ...

, occurred following a strategy of prioritizing agriculture, light industries, and heavy industries in that order.

Infrastructure projects such as the

Sun Yat-sen Freeway,

Taoyuan International Airport

Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport is an international airport serving Taipei and northern Taiwan. Located about west of Taipei in Dayuan District, Taoyuan, the airport is Taiwan's largest. It was also the busiest airport in Taiwan before t ...

,

Taichung Harbor, and

Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant were launched, while the rise of steel, petrochemical, and shipbuilding industries in southern Taiwan saw the transformation of Kaohsiung into a special municipality on par with Taipei. In the 1970s, Taiwan became the second fastest growing economy in Asia after Japan. In 1978, the combination of tax incentives and a cheap, well-trained labor force attracted investments of over $1.9 billion from

overseas Chinese, the United States, and Japan, especially in the manufacturing of electrical and electronic products. By 1980, foreign trade reached $39 billion per year and generated a surplus of $46.5 million, while the income ratio of the highest to the lowest 20 percent of wage earners dropped from 15:1 to 4:1 between 1952 and 1978, less than even that of the United States. Along with Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea, Taiwan became known as one of the

Four Asian Tigers

The Four Asian Tigers (also known as the Four Asian Dragons or Four Little Dragons in Chinese and Korean) are the developed East Asian economies of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Between the early 1960s and 1990s, they underwent ...

.

Because of the Cold War, most Western nations and the United Nations regarded the ROC as the sole legitimate government of China until the 1970s. Eventually, especially after the termination of the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty, most nations switched

diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be accor ...

to the PRC (see United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758). Until the 1970s, the ROC government was regarded by Western critics as undemocratic for upholding

martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

, severely repressing any political opposition, and controlling the media. The KMT did not allow the creation of new parties and those that existed did not seriously compete with the KMT. Thus, competitive democratic elections did not exist. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, however, Taiwan went through reforms and social changes that transformed it from an authoritarian state to a democracy. In 1979, a pro-democracy protest known as the

Kaohsiung Incident

The Kaohsiung Incident, also known as the Formosa Incident, the Meilidao Incident, or the ''Formosa Magazine'' incident,tang was a crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations that occurred in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, on 10 December 1979 during Taiwan's ...

took place in

Kaohsiung to celebrate

Human Rights Day

Human Rights Day is celebrated annually around the world on 10 December every year.

The date was chosen to honor the United Nations General Assembly's adoption and proclamation, on 10 December 1948, of the Universal Declaration of Human Right ...

. Although the protest was rapidly crushed by the authorities, it is today considered as the main event that united Taiwan's opposition.

Chiang Ching-kuo

Chiang Ching-kuo (27 April 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a politician of the Republic of China after its retreat to Taiwan. The eldest and only biological son of former president Chiang Kai-shek, he held numerous posts in the government ...