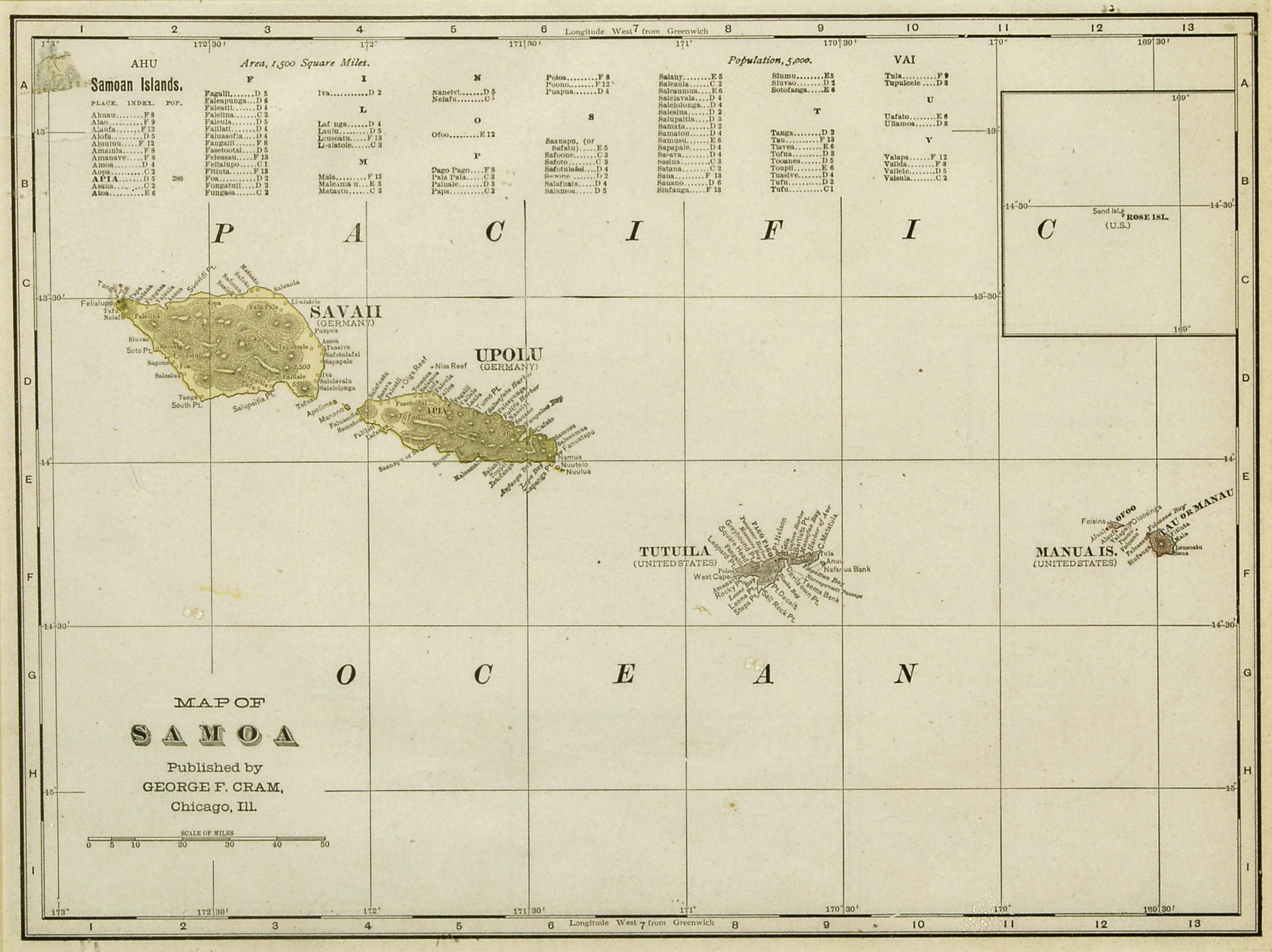

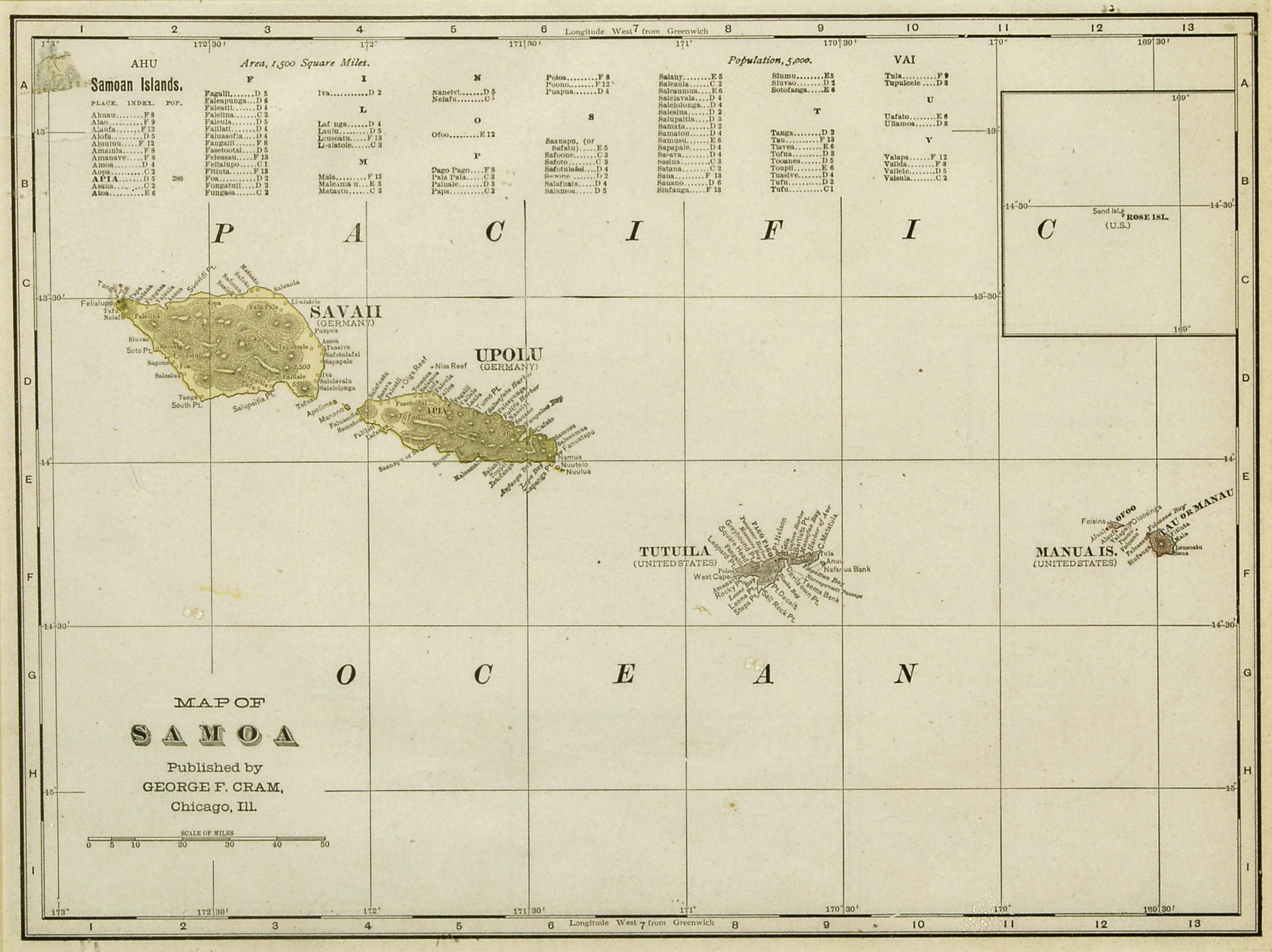

American Samoa ( sm, Amerika Sāmoa, ; also ' or ') is an

unincorporated territory of the United States located in the

South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

, southeast of the

island country

An island country, island state or an island nation is a country whose primary territory consists of one or more islands or parts of islands. Approximately 25% of all independent countries are island countries. Island countries are historically ...

of

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

.

[ Its location is centered on . It is east of the ]International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is an internationally accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between the South and North Poles and serving as the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific ...

, while Samoa is west of the Line. The total land area is , slightly more than Washington, D.C. American Samoa is the southernmost territory of the United States and one of two U.S. territories south of the Equator, along with the uninhabited Jarvis Island

Jarvis Island (; formerly known as Bunker Island or Bunker's Shoal) is an uninhabited coral island located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the Cook Islands. It is an unincorporated, unorganized territory of the Un ...

. Tuna products are the main exports, and the main trading partner is the rest of the United States.

American Samoa consists of five main islands and two coral atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon partially or completely. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical oceans and seas where corals can gro ...

s. The largest and most populous island is Tutuila, with the Manuʻa Islands

The Manua Islands, or the Manua tele (Samoan: ''Manua tele''), in the Samoan Islands, consists of three main islands: Taū, Ofu and Olosega. The latter two are separated only by the shallow, 137-meter-wide Āsaga Strait, and are now connected b ...

, Rose Atoll

Rose Atoll, sometimes called Rose Island or Motu O Manu ("Bird Island") by people of the nearby Manu'a Islands, is an oceanic atoll within the U.S. territory of American Samoa. An uninhabited wildlife refuge, it is the southernmost point belo ...

and Swains Island

Swains Island (; Tokelauan: ''Olohega'' ; Samoan: ''Olosega'' ) is a remote coral atoll in the Tokelau Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The island is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute between Tokelau and the United States, w ...

also included in the territory. All islands except for Swains Island are part of the Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa an ...

, west of the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

, north of Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

, and some south of Tokelau

Tokelau (; ; known previously as the Union Islands, and, until 1976, known officially as the Tokelau Islands) is a dependent territory of New Zealand in the southern Pacific Ocean. It consists of three tropical coral atolls: Atafu, Nukunonu, a ...

. To the west are the islands of the Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, officially the Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands (; french: Wallis-et-Futuna or ', Fakauvea and Fakafutuna: '), is a French island collectivity in the South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji ...

group. As of 2022, the population of American Samoa is approximately 45,443 people.English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

and Samoan fluently.Pacific Community

The Pacific Community (PC), formerly the South Pacific Commission (SPC), is an international development organisation governed by 27 members, including 22 Pacific island countries and territories. The organisation's headquarters are in Nouméa, ...

since 1983. American Samoa is noted for having the highest rate of military enlistment of any U.S. state or territory. As of September 9, 2014, the local U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

recruiting station in Pago Pago

Pago Pago ( ; Samoan: )Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). ''Geology of National Parks''. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. . is the territorial capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County on Tutuila, which is American Samoa's main island. ...

was ranked first in production out of the 885 Army recruiting stations and centers under the United States Army Recruiting Command

The United States Army Recruiting Command (USAREC) is responsible for manning both the United States Army and the Army Reserve. Recruiting operations are conducted throughout the United States, U.S. territories, and at U.S. military facilities i ...

.

American Samoa is the only permanently inhabited territory of the United States in which citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

is not granted at birth, and people born there are considered " non-citizen nationals".

History

Traditional

Traditional oral literature

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used var ...

of Samoa and Manuʻa talks of a widespread Polynesian network or confederacy (or "empire") that was prehistorically ruled by the successive Tui Manuʻa dynasties. Manuan genealogies and religious oral literature also suggest that the Tui Manuʻa had long been one of the most prestigious and powerful paramounts of Samoa. Oral history suggests that the Tui Manuʻa kings governed a confederacy of far-flung islands which included Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

, Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

as well as smaller western Pacific chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

s and Polynesian outliers

Polynesian is the adjectival form of Polynesia. It may refer to:

* Polynesians, an ethnic group

* Polynesian culture, the culture of the indigenous peoples of Polynesia

* Polynesian mythology, the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia

* Poly ...

such as Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau

Tokelau (; ; known previously as the Union Islands, and, until 1976, known officially as the Tokelau Islands) is a dependent territory of New Zealand in the southern Pacific Ocean. It consists of three tropical coral atolls: Atafu, Nukunonu, a ...

, and Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northea ...

. Commerce and exchange routes between the western Polynesian societies are well documented and it is speculated that the Tui Manuʻa dynasty grew through its success in obtaining control over the oceanic trade of currency goods such as finely woven ceremonial mats, whale ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

"tabua

A tabua is a polished tooth of a sperm whale that is an important cultural item in Fijian society. They were traditionally given as gifts for atonement or esteem (called ''sevusevu''), and were important in negotiations between rival chiefs. The ...

", obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements such as silicon ...

and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

tools, chiefly red feathers, and seashells reserved for royalty (such as polished nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in ...

and the egg cowry

Cowrie or cowry () is the common name for a group of small to large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Cypraeidae, the cowries.

The term ''porcelain'' derives from the old Italian term for the cowrie shell (''porcellana'') d ...

).

18th century: First Western contact

Contact with Europeans began in the early 18th century. Dutchman Jacob Roggeveen

Jacob Roggeveen (1 February 1659 – 31 January 1729) was a Dutch explorer who was sent to find Terra Australis and Davis Land, but instead found Easter Island (called so because he landed there on Easter Sunday). Jacob Roggeveen also found Bora ...

was the first known European to sight the Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa an ...

in 1722, calling them the "Baumann Islands" after one of his captains. The next explorer to visit the islands was Louis-Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (, , ; 12 November 1729 – August 1811) was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of the British explorer James Cook, he took part in the Seven Years' War in North America and the American Revolution ...

, who named them the "Îles des Navigateurs" in 1768. British explorer James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

recorded the island names in 1773, but never visited.[

HMS ''Pandora'', under the command of Admiral Edward Edwards (Royal Navy officer), visited the island in 1791 during its search for the H.M.S. ''Bounty'' mutineers. Von Kotzebue visited in 1824.][

]

19th century

Mission work in the Samoas had begun in late 1830 when John Williams

John Towner Williams (born February 8, 1932)Nylund, Rob (15 November 2022)Classic Connection review '' WBOI'' ("For the second time this year, the Fort Wayne Philharmonic honored American composer, conductor, and arranger John Williams, who w ...

of the London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed in outlook, with Congregational m ...

arrived from the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

and Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

. By the late nineteenth century, French, British, German, and American vessels routinely stopped at Samoa, as they valued Pago Pago Harbor as a refueling station for coal-fired shipping and whaling.

The United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

visited the islands in 1839.

In March 1889, an Imperial German naval force entered a village in Samoa, and in doing so destroyed some American property. Three American warships then entered the

In March 1889, an Imperial German naval force entered a village in Samoa, and in doing so destroyed some American property. Three American warships then entered the Apia

Apia () is the capital and largest city of Samoa, as well as the nation's only city. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

...

harbor and prepared to engage the three German warships found there. Before any shots were fired, a typhoon wrecked both the American and German ships. A compulsory armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

was then called because of the lack of any warships.

20th century

Early 20th century

At the turn of the twentieth century, international rivalries in the latter half of the century were settled by the 1899

At the turn of the twentieth century, international rivalries in the latter half of the century were settled by the 1899 Tripartite Convention

The Tripartite Convention of 1899 concluded the Second Samoan Civil War, resulting in the formal partition of the Samoan archipelago into a German colony and a United States territory.

Forerunners to the Tripartite Convention of 1899 were the ...

in which Germany and the United States partitioned the Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa an ...

into two: the eastern island group became a territory of the United States (Tutuila in 1900 and officially Manuʻa in 1904)German Samoa

German Samoa (german: Deutsch-Samoa) was a German protectorate from 1900 to 1920, consisting of the islands of Upolu, Savai'i, Apolima and Manono, now wholly within the independent state of Samoa, formerly ''Western Samoa''. Samoa was the la ...

, after Britain gave up all claims to Samoa and in return accepted the termination of German rights in Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

and certain areas in the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

and West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

. Forerunners to the Tripartite Convention

The Tripartite Convention of 1899 concluded the Second Samoan Civil War, resulting in the formal partition of the Samoan archipelago into a German colony and a United States territory.

Forerunners to the Tripartite Convention of 1899 were the ...

of 1899 were the Washington Conference of 1887, the Treaty of Berlin of 1889 and the Anglo-German Agreement on Samoa of 1899.

American colonization

The following year, the U.S. formally

The following year, the U.S. formally annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

its portion, a smaller group of eastern islands, one of which contains the noted harbor of Pago Pago

Pago Pago ( ; Samoan: )Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). ''Geology of National Parks''. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. . is the territorial capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County on Tutuila, which is American Samoa's main island. ...

.[Lin, Tom C.W.]

Americans, Almost and Forgotten

107 California Law Review (2019) After the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

took possession of eastern Samoa for the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

, the existing coaling station

Fuelling stations, also known as coaling stations, are repositories of fuel (initially coal and later oil) that have been located to service commercial and naval vessels. Today, the term "coaling station" can also refer to coal storage and feedi ...

at Pago Pago Bay was expanded into a full naval station A Naval Station was a geographic command responsible for conducting all naval operations within its defined area. It may consist of flotillas, or squadrons, or individual ships under command.

The British Royal Navy for command purposes was separ ...

, known as United States Naval Station Tutuila and commanded by a commandant. The Navy secured a Deed of Cession of Tutuila in 1900 and a Deed of Cession of Manuʻa in 1904 on behalf of the U.S. government. The last sovereign of Manuʻa, the Tui Manuʻa Elisala, signed a Deed of Cession of Manuʻa following a series of U.S. naval trials, known as the "Trial of the Ipu", in Pago Pago, Taʻu, and aboard a Pacific Squadron

The Pacific Squadron was part of the United States Navy squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval s ...

gunboat. The territory became known as the U.S. Naval Station Tutuila.

On July 17, 1911, the U.S. Naval Station Tutuila, which was composed of Tutuila, Aunuʻu and Manuʻa, was officially renamed American Samoa. People of Manuʻa had been unhappy since they were left out of the name "Naval Station Tutuila". In May 1911, Governor William Michael Crose authored a letter to the Secretary of the Navy conveying the sentiments of Manuʻa. The department responded that the people should choose a name for their new territory. The traditional leaders chose “American Samoa”, and, on July 7, 1911, the solicitor general of the Navy authorized the governor to proclaim it as the name for the new territory.

World War I and the 1918 influenza pandemic

In 1918, during the final stages of

In 1918, during the final stages of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the Great Influenza epidemic had taken its toll, spreading rapidly from country to country. American Samoa became one of the only places in the world (the others being New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

and Marajó island

Marajó () is a large coastal island in the Pará, state of Pará, Brazil. It is the main and largest of the islands in the Marajó Archipelago. Marajó Island is separated from the mainland by Marajó Bay, Pará River, smaller rivers (especi ...

in Brazil) to have proactively prevented any deaths during the pandemic through the quick response from Governor John Martin Poyer after hearing news reports of the outbreak on the radio and requesting quarantine ships from the U.S. mainland. The result of Poyer's quick actions earned him the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

from the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

. With this distinction, American Samoans regarded Poyer as their hero for what he had done to prevent the deadly disease. The neighboring New Zealand territory at the time, Western Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, suffered the most of all Pacific islands

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

, with 90% of the population infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women and 10% of children died. Poyer offered assistance to help his New Zealand counterparts but was refused by the administrator of Western Samoa, Robert Logan, who became outraged after witnessing the number of quarantine ships surrounding American Samoa. Angered by this, Logan cut off communications with his American counterparts.

Interwar period

=American Samoa Mau movement

=

After World War I, during the time of the Mau movement

The Mau was a non-violent movement for Samoan independence from colonial rule during the first half of the 20th century. ''Mau'' means ‘resolute’ or ‘resolved’ in the sense of ‘opinion’, ‘unwavering’, ‘to be decided’, ...

in Western Samoa (then a League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

mandate governed by New Zealand), there was a corresponding American Samoa Mau movement led by Samuelu Ripley, a World War I veteran who was from Leone village, Tutuila. After meetings on the United States mainland, he was prevented from disembarking from the ship that brought him home to American Samoa and was not allowed to return because the American Samoa Mau movement was suppressed by the U.S. Navy. In 1930 the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

sent a committee to investigate the status of American Samoa, led by Americans who had a part in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

.

=Annexation of Swains Island

=

Swains Island

Swains Island (; Tokelauan: ''Olohega'' ; Samoan: ''Olosega'' ) is a remote coral atoll in the Tokelau Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The island is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute between Tokelau and the United States, w ...

, which had been included in the list of guano islands appertaining to the United States and bonded under the Guano Islands Act

The Guano Islands Act (, enacted August 18, 1856, codified at §§ 1411-1419) is a United States federal law passed by the U.S. Congress that enables citizens of the United States to take possession, in the name of the United States, of unclai ...

, was annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

in 1925 by Pub. Res. 68–75, following the dissolution of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony

The Gilbert and Ellice Islands (GEIC as a colony) in the Pacific Ocean were part of the British Empire from 1892 to 1976. They were a protectorate from 1892 to 12 January 1916, and then a colony until 1 January 1976. The history of the colony w ...

by the United Kingdom.

World War II and aftermath

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, U.S. Marines stationed in Samoa outnumbered the local population and had a huge cultural influence. Young Samoan men from age 14 and above were combat trained by U.S. military personnel. Samoans served in various capacities during World War II, including as combatants, medical personnel, code personnel, and ship repairmen.

In 1949, Organic Act 4500, a U.S. Department of Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the man ...

–sponsored attempt to incorporate American Samoa, was introduced in Congress. It was ultimately defeated, primarily through the efforts of Samoan chiefs, led by Tuiasosopo Mariota. The efforts of these chiefs led to the creation of a territorial legislature, the American Samoa Fono

The American Samoa Fono is the territorial legislature of American Samoa. Like most states and territorial legislatures of the United States, it is a bicameral legislature with a House of Representatives and a Senate. The legislature is lo ...

, which meets in the village of Fagatogo

Fagatogo is the downtown area of Pago Pago (the territorial capital of American Samoa).Grabowski, John F. (1992). ''U.S. Territories and Possessions (State Report Series)''. Chelsea House Pub. Page 51. . Located in the low grounds at the foot of M ...

. In 1950 the Department of the Interior began to administer the American Samoa.

1951–1999

By 1956, the U.S. Navy-appointed governor was replaced by

By 1956, the U.S. Navy-appointed governor was replaced by Peter Tali Coleman

Peter Tali Coleman (December 8, 1919 – April 28, 1997) was an American Samoan politician and lawyer. Coleman was the first and only person of Samoan descent to be appointed Governor of American Samoa between 1956 and 1961, and later became ...

, who was locally elected. Although technically considered "unorganized" since the U.S. Congress has not passed an Organic Act

In United States law, an organic act is an act of the United States Congress that establishes a territory of the United States and specifies how it is to be governed, or an agency to manage certain federal lands. In the absence of an organ ...

for the territory, American Samoa is self-governing under a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

that became effective on July 1, 1967. The U.S. Territory of American Samoa is on the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories

Chapter XI of the United Nations Charter defines a non-self-governing territory (NSGT) as a territory "whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government". In practice, an NSGT is a territory deemed by the United Nations Gene ...

, a listing which is disputed by the territorial government officials, who do consider themselves to be self-governing.

American Samoa and Pago Pago International Airport

Pago Pago International Airport , also known as Tafuna Airport, is a public airport located 7 miles (11.3 km) southwest of the central business district of Pago Pago, in the village and plains of Tafuna on the island of Tutuila in American ...

had historic significance with the Apollo Program. The astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally r ...

crews of Apollo 10

Apollo 10 (May 18–26, 1969) was a human spaceflight, the fourth crewed mission in the United States Apollo program, and the second (after Apollo8) to orbit the Moon. NASA described it as a "dress rehearsal" for the first Moon landing, and ...

, 12, 13, 14, and 17 were retrieved a few hundred miles from Pago Pago and transported by helicopter to the airport prior to being flown to Honolulu on C-141 Starlifter

The Lockheed C-141 Starlifter is a retired military strategic airlifter that served with the Military Air Transport Service (MATS), its successor organization the Military Airlift Command (MAC), and finally the Air Mobility Command (AMC) of the ...

military aircraft.

While the two Samoas share language and ethnicity, their cultures have recently followed different paths, with American Samoans often emigrating to Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

and the U.S. mainland, and adopting many U.S. customs, such as the playing of American football

American football (referred to simply as football in the United States and Canada), also known as gridiron, is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular field with goalposts at each end. The offense, the team wi ...

and baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

. Samoans

Samoans or Samoan people ( sm, tagata Sāmoa) are the indigenous Polynesian people of the Samoan Islands, an archipelago in Polynesia, who speak the Samoan language. The group's home islands are politically and geographically divided between t ...

have tended to emigrate instead to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, whose influence has made the sports of rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

and cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

more popular in the western Samoan islands. Travel writer Paul Theroux

Paul Edward Theroux (born April 10, 1941) is an American novelist and travel writer who has written numerous books, including the travelogue, ''The Great Railway Bazaar'' (1975). Some of his works of fiction have been adapted as feature films. He ...

noted that there were marked differences between the societies in Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

and American Samoa.

21st century

American Samoans have a high rate of service in the U.S. Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

. Because of economic hardship, military service has been seen as an opportunity in American Samoa and other U.S. Overseas territories. As of March 23, 2009, ten American Samoans had died in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, and two had died in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

.

Notable events

Pre-20th century

On December 13, 1784, French navigator

On December 13, 1784, French navigator Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse

Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse (; variant spelling: ''La Pérouse''; 23 August 17411788?), often called simply Lapérouse, was a French naval officer and explorer. Having enlisted at the age of 15, he had a successful naval caree ...

landed two exploration parties on Tutuila's north shore: one from the ship '' La Boussole'' at Fagasa, and the other from ''L'Astrolabe

''Astrolabe'' was originally a horse-transport barge converted into an exploration ship of the French Navy. Originally named ''Coquille'', she is famous for her travels with Jules Dumont d'Urville. The name derives from an early navigational in ...

'' at Aʻasu. One of the cooks, David, died of "scorbutic dropsy". On December 11, twelve members of Lapérouse's crew (including First Officer Paul Antoine Fleuriot de Langle

Paul Antoine Fleuriot de Langle (1 August 1744, château de Kerlouët at Quemper-Guézennec, Côtes-d'Armor – 11 December 1787, Maouna, Samoa) was a French vicomte, académicien de marine, naval commander and explorer. He was second in c ...

) were killed by angry Samoans at Aʻasu Bay, Tutuila, thereafter known as "Massacre Bay", which Lapérouse described as "this den, more fearful from its treacherous situation and the cruelty of its inhabitants than the lair of a lion or a tiger". This incident gave Samoa a reputation for savagery that kept Europeans away until the arrival of the first Christian missionaries four decades later. On December 12, at Aʻasu Bay, Lapérouse ordered his gunners to fire one cannonball amid the attackers who had killed his men the day before and were now returning to launch another attack. He later wrote in his journal "I could have destroyed or sunk a hundred canoes, with more than 500 people in them: but I was afraid of striking the wrong victims; the call of my conscience saved their lives."

20th century

On December 19, 1912, English writer

On December 19, 1912, English writer William Somerset Maugham

William Somerset Maugham ( ; 25 January 1874 – 16 December 1965) was an English writer, known for his plays, novels and short stories. Born in Paris, where he spent his first ten years, Maugham was schooled in England and went to a German un ...

arrived in Pago Pago, allegedly accompanied by a missionary and Miss Sadie Thompson. His visit inspired his short story "Rain

Rain is water droplets that have condensed from atmospheric water vapor and then fall under gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is responsible for depositing most of the fresh water on the Earth. It provides water f ...

" which later became plays and three major motion pictures. The building still stands where Maugham stayed and has been renamed the Sadie Thompson Building. Today it is a prominent restaurant and inn.

On November 2, 1921, American Samoa's 13th naval governor, Commander Warren Jay Terhune, died by suicide with a pistol in the bathroom of the government mansion, overlooking the entrance to Pago Pago Harbor. His body was discovered by Government House's cook, SDI First Class Felisiano Debid Ahchica, USN. His ghost is rumored to walk about the grounds at night.

On August 17, 1924,

On August 17, 1924, Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901 – November 15, 1978) was an American cultural anthropologist who featured frequently as an author and speaker in the mass media during the 1960s and the 1970s.

She earned her bachelor's degree at Barnard C ...

arrived in American Samoa aboard the SS ''Sonoma'' to begin fieldwork for her doctoral dissertation in anthropology at Columbia University, where she was a student of Professor Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

. Her work ''Coming of Age in Samoa

''Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation'' is a 1928 book by American anthropologist Margaret Mead based upon her research and study of youth – primarily adolescent girls – on the island of ...

'' was published in 1928, at the time becoming the most widely read book in the field of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

. The book has sparked years of ongoing and intense debate and controversy. Mead returned to American Samoa in 1971 for the dedication of the Jean P. Haydon Museum.

In 1938, the noted aviator

In 1938, the noted aviator Ed Musick

Edwin Charles Musick (August 13, 1894 – January 11, 1938) was chief pilot for Pan American World Airways and pioneered many of Pan Am's transoceanic routes including the famous route across the Pacific Ocean on the ''China Clipper''.

Biogra ...

and his crew died on the Pan American World Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United State ...

S-42 ''Samoan Clipper

''Samoan Clipper'' was one of ten Pan American Airways Sikorsky S-42 flying boats. It exploded near Pago Pago, American Samoa, on January 11, 1938, while piloted by aviator Ed Musick. Musick and his crew of six died in the crash. The aircraft was ...

'' over Pago Pago, while on a survey flight to Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

. Sometime after takeoff, the aircraft experienced trouble, and Musick turned it back toward Pago Pago. While the crew dumped fuel in preparation for an emergency landing, an explosion occurred that tore the aircraft apart.

On November 21, 1939, American Samoa's last execution was carried out. Imoa was convicted of stabbing Sema to death and was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The '' Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

in the Customs House

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

. The popular Samoan song "Faʻafofoga Samoa" is based on this, said to be the final words of Imoa.

On January 13, 1942, at 2:26am, a Japanese submarine surfaced off Tutuila between Southworth Point and Fagasa Bay and fired about 15 shells from its 5.5-inch deck gun at the U.S. Naval Station Tutuila over the next 10 minutes. The first shell struck the rear of Frank Shimasaki's store, ironically owned by one of Tutuila's few Japanese residents. The store was closed, as Mr. Shimasaki had been interned as an enemy alien. The next shell caused slight damage to the naval dispensary, the third landed on the lawn behind the naval quarters known as "Centipede Row," and the fourth struck the stone seawall outside the customs house. The other rounds fell harmlessly into the harbor. As one writer described it, "The fire was not returned, notwithstanding the eagerness of the Samoan Marines to test their skill against the enemy... No American or Samoan Marines were wounded."shrapnel

Shrapnel may refer to:

Military

* Shrapnel shell, explosive artillery munitions, generally for anti-personnel use

* Shrapnel (fragment), a hard loose material

Popular culture

* ''Shrapnel'' (Radical Comics)

* ''Shrapnel'', a game by Adam C ...

, and "a member of the colorful native Fita Fita Guard" received minor injuries; they were the only casualties. This was the only time the Japanese attacked Tutuila during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, although "Japanese submarines had patrolled the waters around Samoa before the war, and continued to be active there throughout the war."Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

visited American Samoa and inspected the Fita Fita Guard and Band and the First Samoan Battalion of U.S. Marine Corps Reserve at the U.S. Naval Station American Samoa.[Shaffer, Robert J. (2000). ''American Samoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag''. Island Heritage. .] The fact that First Lady reviewed the troops led to further assurance that Tutuila Island was considered safe. Her presence underscored that World War II had passed by American Samoa. While the Fita Fita band played, Eleanor Roosevelt inspected the guard.[Ruck, Rob (2018). ''Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans to the NFL''. The New Press. .]

On October 18, 1966, President Lyndon Baines Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

and First Lady Lady Bird Johnson

Claudia Alta "Lady Bird" Johnson (''née'' Taylor; December 22, 1912 – July 11, 2007) was First Lady of the United States from 1963 to 1969 as the wife of President Lyndon B. Johnson. She previously served as Second Lady from 1961 to 1963 whe ...

visited American Samoa. Mrs. Johnson dedicated the "Manulele Tausala" ("Lady Bird") Elementary School in Nuʻuuli, which was named after her. Johnson is the only US president to have visited American Samoa, while Mrs. Johnson was the second First Lady, preceded by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1943.LBJ Tropical Medical Center

Lyndon B. Johnson Tropical Medical Center is the only hospital in American Samoa, and is located in Faga'alu, Maoputasi County. It has been ranked among the best hospitals in the Pacific Ocean. It is home to an emergency room and there are docto ...

in honor of President Johnson.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, American Samoa played a pivotal role in five of the Apollo Program missions. The astronauts landed several hundred miles from Pago and were transported to the islands en route back to the mainland. President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

gave three moon rocks to the American Samoan government, and these are on display in the Jean P. Haydon Museum, along with a flag carried to the moon on one of the missions.

In November 1970, Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

visited American Samoa in a brief but lavish greeting.Pan Am Flight 806

Pan Am Flight 806 was an international scheduled flight from Auckland, New Zealand, to Los Angeles, California, with intermediate stops at Pago Pago, American Samoa and Honolulu, Hawaii. On January 30, 1974, the Boeing 707 ''Clipper Radiant'' cra ...

from Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

, New Zealand crashed at Pago Pago International Airport at 10:41pm, with 91 passengers aboard. 86 people were killed, including Captain Leroy A. Petersen and the entire flight crew. Four of the five surviving passengers were seriously injured, with the other only slightly injured. The airliner was destroyed by the impact and succeeding fire. The crash was attributed to poor visibility, pilot error, or wind shear since a violent storm was raging at the time. In January 2014, filmmaker Paul Crompton visited the territory to interview local residents for a documentary film about the 1974 crash.

A U.S. Navy P-3 Orion

The Lockheed P-3 Orion is a four-engined, turboprop Anti-submarine warfare, anti-submarine and maritime patrol aircraft, maritime surveillance aircraft developed for the United States Navy and introduced in the 1960s. Lockheed Corporation, Lockh ...

patrol plane from Patrol Squadron 50 (VP-50) had its vertical stabilizer shorn off by the Solo Ridge-Mount Alava aerial tramway

An aerial tramway, sky tram, cable car, ropeway, aerial tram, telepherique, or seilbahn is a type of aerial lift which uses one or two stationary ropes for support while a third moving rope provides propulsion. With this form of lift, the grip ...

cable across Pago Pago harbor on April 17, 1980, during the Flag Day celebrations, when carrying six skydivers from the U.S. Army's Hawaii-based Tropic Lightning Parachute Club. The plane crashed, demolishing a wing of the Rainmaker Hotel

Rainmaker Hotel was a 250-room luxury hotel in Utulei, Pago Pago, American Samoa. It was the only proper hotel in American Samoa and was operated by the government. The hotel was at its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, when it was known as the Pacific ...

and killing all six crew members and one civilian. The six skydivers had already left the aircraft during a demonstration jump. A memorial monument is erected on Mt. Mauga O Aliʻi to honor their memory.

On November 1, 1988, President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

signed a bill which created American Samoa National Park

The National Park of American Samoa is a national park in the United States territory of American Samoa, distributed across three islands: Tutuila, Ofu, and Ta‘ū. The park preserves and protects coral reefs, tropical rainforests, fruit bats ...

.

21st century

On July 22, 2010, Detective Lieutenant Lusila Brown was fatally shot outside the temporary High Court building in Fagatogo. It was the first time in more than 15 years that a police officer was killed in the line of duty. The last was Sa Fuimaono, who drowned after saving a teenager from rough seas.

On November 8, 2010, United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

and former First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non- monarchical head of state or chief executive. The term is also used to describe a woman seen to be at the ...

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

made a refueling stopover at the Pago Pago International Airport

Pago Pago International Airport , also known as Tafuna Airport, is a public airport located 7 miles (11.3 km) southwest of the central business district of Pago Pago, in the village and plains of Tafuna on the island of Tutuila in American ...

. She was greeted by government dignitaries and presented with gifts and a traditional ava ceremony.

Mike Pence

Michael Richard Pence (born June 7, 1959) is an American politician who served as the 48th vice president of the United States from 2017 to 2021 under President Donald Trump. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as the 50th ...

was the third sitting U.S. vice president to visit American Samoa (after Dan Quayle

James Danforth Quayle (; born February 4, 1947) is an American politician who served as the 44th vice president of the United States from 1989 to 1993 under President George H. W. Bush. A member of the Republican Party, Quayle served as a U.S. ...

and Joe Biden) when he made a stopover in Pago Pago in April 2017. He addressed 200 soldiers here during his refueling stop. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson

Rex Wayne Tillerson (born March 23, 1952) is an American engineer and energy executive who served as the 69th U.S. secretary of state from February 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018, under President Donald Trump. Prior to joining the Trump administ ...

visited town on June 3, 2017.

September 2009 earthquake and tsunami

On September 28, 2009, at 17:48:11 UTC, an 8.1

On September 28, 2009, at 17:48:11 UTC, an 8.1 magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

struck off the coast of American Samoa, followed by smaller aftershocks. It was the largest

Large means of great size.

Large may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Arbitrarily large, a phrase in mathematics

* Large cardinal, a property of certain transfinite numbers

* Large category, a category with a proper class of objects and morphisms (o ...

earthquake of 2009. The quake occurred on the outer rise of the Kermadec-Tonga Subduction Zone

The Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone is a convergent plate boundary that stretches from the North Island of New Zealand northward. The formation of the Kermadec and Tonga Plates started about 4–5 million years ago. Today, the eastern boundary o ...

. This is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occur. The Ring ...

, where tectonic plates

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

in the Earth's lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

meet, and earthquakes and volcanic activity are common. The quake struck below the ocean floor and generated an onsetting tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

that killed more than 170 people in the Samoa Islands and Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

. Four waves with heights from to high were reported to have reached up to one mile (1.6km) inland on the island of Tutuila.

The Defense Logistics Agency

The Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) is a combat support agency in the United States Department of Defense (DoD), with more than 26,000 civilian and military personnel throughout the world. Located in 48 states and 28 countries, DLA provides su ...

worked with the Federal Emergency Management Agency

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS), initially created under President Jimmy Carter by Presidential Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1978 and implemented by two Ex ...

to provide 16' × 16' humanitarian tents to the devastated areas of American Samoa.

Government and politics

Government

American Samoa is classified in U.S. law as an unincorporated territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sove ...

; the Ratification Act of 1929 vested all civil, judicial, and military powers in the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

.Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

. On June 21, 1963 Paramount Chief Tuli Leʻiato of Fagaʻitua was sworn in and installed as the first Secretary of Samoan Affairs by Governor H. Rex Lee

Hyrum Rex Lee (April 8, 1910 – July 26, 2001) was an American government employee and diplomat who was the last non-elected Governor of American Samoa. Lee served as governor from 1961 to 1967, and again briefly from 1977 to 1978. Governor Lee ...

. On June 2, 1967, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall

Stewart Lee Udall (January 31, 1920 – March 20, 2010) was an American politician and later, a federal government official. After serving three terms as a congressman from Arizona, he served as Secretary of the Interior from 1961 to 1969, und ...

promulgated the Revised Constitution of American Samoa, which took effect on July 1, 1967.[

] The

The Governor of American Samoa

This is a list of governors, etc. of the part of the Samoan Islands (now comprising American Samoa) under United States administration since 1900.

From 1900 to 1978 governors were appointed by the Federal government of the United States. Sinc ...

is the head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a ...

and along with the Lieutenant Governor of American Samoa

The government of American Samoa consists of a locally elected governor, lieutenant governor and the American Samoa Fono, which consists of an 18-member Senate and a 21-member House of Representatives. The first popular election for Governor and ...

is elected on the same ticket by popular vote for a four-year term. The governor's office is located in Utulei.[ Since American Samoa is a U.S. territory, the President of the United States serves as the ]head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

but does not play a direct role in government. The Secretary of the Interior oversees the government, retaining the power to approve constitutional amendments, overrides the governor's veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

es, and nomination of justices.[

The ]legislative power

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known a ...

is vested in the American Samoa Fono

The American Samoa Fono is the territorial legislature of American Samoa. Like most states and territorial legislatures of the United States, it is a bicameral legislature with a House of Representatives and a Senate. The legislature is lo ...

, which has two chambers. The House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

has 21 members serving two-year terms, being 20 representatives popularly elected from various districts and one non-voting delegate from Swains Island

Swains Island (; Tokelauan: ''Olohega'' ; Samoan: ''Olosega'' ) is a remote coral atoll in the Tokelau Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The island is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute between Tokelau and the United States, w ...

elected in a public meeting. The Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

has 18 members, elected for four-year terms by and from the chiefs of the islands.[ The Fono is located in ]Fagatogo

Fagatogo is the downtown area of Pago Pago (the territorial capital of American Samoa).Grabowski, John F. (1992). ''U.S. Territories and Possessions (State Report Series)''. Chelsea House Pub. Page 51. . Located in the low grounds at the foot of M ...

.[

The ]judiciary of American Samoa The Judiciary of American Samoa is defined under the Constitution of American Samoa and the American Samoa Code. It consists of the High Court of American Samoa, a District Court, and village courts, all under the administration and supervision of t ...

is composed of the High Court of American Samoa

The High Court of American Samoa is a Samoan court and the highest court below the United States Supreme Court in American Samoa. The Court is located in the capital of Fagatogo. It consists of one chief justice and one associate justice, appo ...

, a District Court, and village courts. The High Court and District Court are located in Fagatogo, near the Fono.[ The High Court is led by a Chief Justice and an Associate Justice, appointed by the Secretary of the Interior. Other judges are appointed by the governor upon the recommendation of the Chief Justice and confirmed by the Senate.

]

Politics

American Samoa is an unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States, administered by the Office of Insular Affairs

The Office of Insular Affairs (OIA) is a unit of the United States Department of the Interior that oversees federal administration of several United States insular areas. It is the successor to the Bureau of Insular Affairs of the War Departme ...

, U.S. Department of the Interior. American Samoa's constitution was ratified in 1966 and came into effect in 1967.

However, despite being de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

unorganized, American Samoa is de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

organized, with its politics taking place in the framework of a presidential representative democratic

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represe ...

dependency, whereby the Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

is the head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a ...

, and of a pluriform multi-party system

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in ...

.

Executive power

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems b ...

is exercised by the governor. Legislative power

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known a ...

is vested in the two chambers of the legislature. The American political parties (Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and Democratic) exist in American Samoa, but few politicians are aligned with the parties. The judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

is independent of the executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive di ...

and the legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

.

There is also the traditional village politics of the Samoa Islands, the "faʻamatai

''Fa'amatai'' is the indigenous political ('chiefly') system of Samoa, central to the organization of Samoan society. It is the traditional indigenous form of governance in both Samoas, comprising American Samoa and the Independent State of S ...

" and the " faʻa Sāmoa", which continues in American Samoa and independent Samoa, and which interacts across these current boundaries. The faʻa Sāmoa is the language and customs, and the faʻamatai are the protocols of the "fono" (council) and the chief system. The faʻamatai and the fono take place at all levels of the Samoan body politic, from the family to the village, to the region, to national matters.

The ʻaiga is the family unit of Samoan society, which differs from the Western sense of a family in that it consists of an "extended family" based on the culture's communal socio-political

Political sociology is an interdisciplinary field of study concerned with exploring how governance and society interact and influence one another at the micro to macro levels of analysis. Interested in the social causes and consequences of how ...

organization. The head of the ʻaiga is the matai. The matai (chiefs) are elected by consensus within the fono of the extended family and village(s) concerned. The matai and the fono, which are themselves made of matai, decide on the distribution of family exchanges and tenancy of communal lands. The majority of lands in American Samoa and independent Samoa are communal. A matai can represent a small family group or a great extended family that reaches across islands and to both American Samoa and independent Samoa.

In 2010, voters rejected a package of amendments to the territorial constitution, which would have, among other things, allowed U.S. citizens to be legislators only if they had Samoan ancestry.

In 2012, both the Governor and American Samoa's delegate to the U.S. Congress Eni Faleomavaega

Eni Fa'aua'a Hunkin Faleomavaega Jr. (; August 15, 1943 – February 22, 2017) was an American Samoan politician and attorney who served as the territory's lieutenant governor (1985-1989) and non-voting delegate to the United States House of Repr ...

called for the populace to consider a move towards autonomy if not independence, with a mixed response.

Nationality

According to the Immigration and Nationality Act The U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act may refer to one of several acts including:

* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952

* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

* Immigration Act of 1990

See also

* List of United States immigration legis ...

(INA), the people born in American Samoa—including those born on Swains Island

Swains Island (; Tokelauan: ''Olohega'' ; Samoan: ''Olosega'' ) is a remote coral atoll in the Tokelau Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The island is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute between Tokelau and the United States, w ...

—are " nationals but not citizens of the United States

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

at birth". If a child is born on any of these islands to any U.S. citizen, then that child is considered a national and a citizen of the United States at birth. All U.S. nationals have statutory rights to reside in all parts of the United States, and may apply for citizenship by naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

after three months of residency by paying a fee, passing a test in English and civics, and taking an oath of allegiance to the United States. All U.S. nationals also have the right to work in the United States, except in certain government jobs that specifically require U.S. citizenship.

In 2012, a group of American Samoans sued the federal government seeking recognition of birthright citizenship for American Samoans in the case '' Tuaua v. United States''. In an amicus curiae

An ''amicus curiae'' (; ) is an individual or organization who is not a party to a legal case, but who is permitted to assist a court by offering information, expertise, or insight that has a bearing on the issues in the case. The decision o ...

brief filed in federal court, American Samoan Congressman Faleomavaega supported the legal interpretation that the Citizenship Clause

The Citizenship Clause is the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted on July 9, 1868, which states:

This clause reversed a portion of the ''Dred Scott v. Sandford'' decision, which had d ...

of the Fourteenth Amendment does not extend birthright citizenship

''Jus soli'' ( , , ; meaning "right of soil"), commonly referred to as birthright citizenship, is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship.

''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contras ...

to United States nationals born in unincorporated territories. In June 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia affirmed that Fourteenth Amendment citizenship guarantees did not apply to persons born in unincorporated territories and a year later the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the lower court's decision.

In December 2019, U.S. District Judge Clark Waddoups

Clark Waddoups (born April 21, 1946) is a senior United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Utah.

Education and legal career

Waddoups received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Brigham Young University ...

struck down as facially unconstitutional, holding that "Persons born in American Samoa are citizens of the United States by the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment", but the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (in case citations, 10th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* District of Colorado

* District of Kansas

* Distr ...

reversed the district court's judgment and found the statute constitutional. On July 20, 2021, the Legislature of American Samoa unanimously passed a resolution in support of the 10th Circuit Court's decision to reverse.

=Voting rights

=

As U.S. nationals, American Samoans can vote in local elections in the territory; however, if they live in other parts of the United States, they are not allowed to vote in federal, state or the vast majority of local elections unless they become U.S. citizens. The only federal office American Samoans elect directly is a non-voting delegate to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. Since the delegate's office was created in 1978, three people have held the seat: Democrat Fofō Iosefa Fiti Sunia (1981–1988); Democrat Eni Faleomavaega

Eni Fa'aua'a Hunkin Faleomavaega Jr. (; August 15, 1943 – February 22, 2017) was an American Samoan politician and attorney who served as the territory's lieutenant governor (1985-1989) and non-voting delegate to the United States House of Repr ...

(1989–2015); and Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Aumua Amata Radewagen

Amata Catherine Coleman Radewagen (born December 29, 1947), commonly called Aumua Amata , is an American Samoan politician who is the current delegate for the United States House of Representatives from American Samoa. Radewagen, a Republican, ...

(2015–) American Samoans also participate in partisan presidential primaries

The presidential primary elections and caucuses held in the various states, the District of Columbia, and territories of the United States form part of the nominating process of candidates for United States presidential elections. The United S ...

, as well as send delegates to the Democratic and Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

National Conventions.

Immigration

Unique among U.S. territories, American Samoa has its own immigration law, separate from the laws that apply in other parts of the United States. U.S. nationals may freely reside in American Samoa. The American Samoan government, via its Immigration Office, controls the migration of foreign nationals to the islands. Special application forms exist for migration to American Samoa based on family or employment sponsorship.

Unlike all other permanently inhabited U.S. jurisdictions ( states, District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.), Logan Circle, Jefferson Memoria ...

, Puerto Rico