Reginald McKenna on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

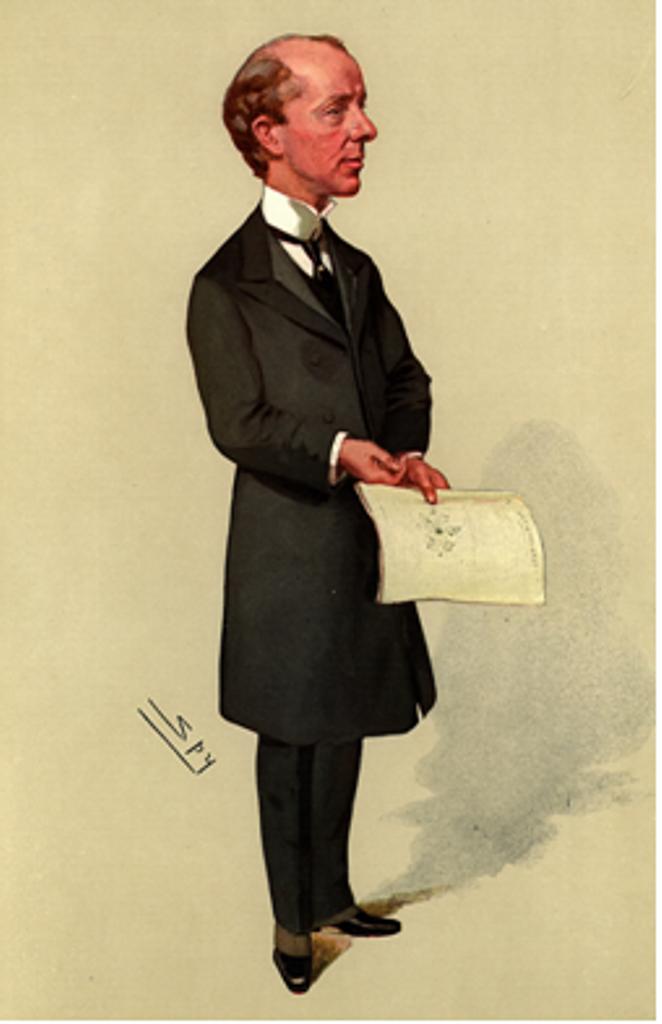

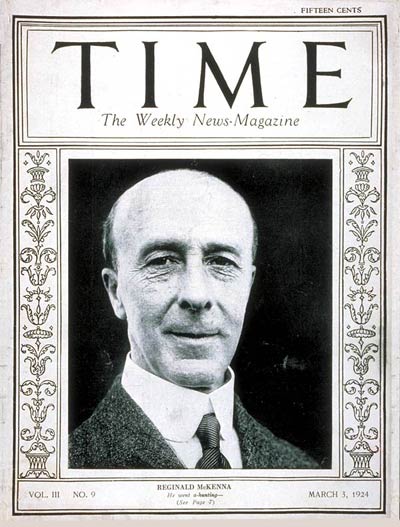

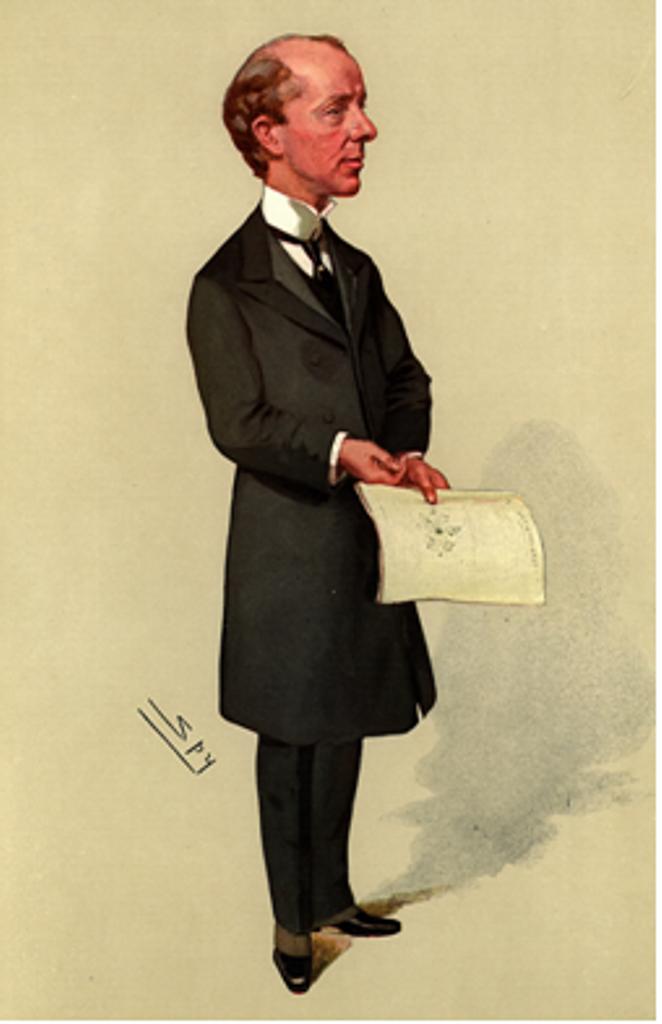

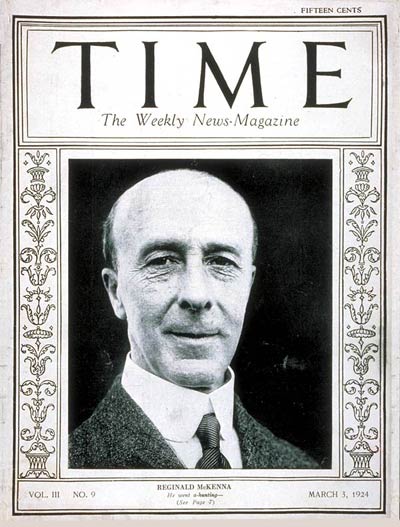

Reginald McKenna (6 July 1863 – 6 September 1943) was a British banker and

In December 1905 McKenna was appointed, in preference to

In December 1905 McKenna was appointed, in preference to  In 1907 James Bryce was appointed Ambassador to the US,

In 1907 James Bryce was appointed Ambassador to the US,

On 13 March 1913 he voted against compulsory military training.

At a "council of war" with Lloyd George on 13 June, McKenna was left in no doubt that Asquith had refused the chancellor's resignation over the

On 13 March 1913 he voted against compulsory military training.

At a "council of war" with Lloyd George on 13 June, McKenna was left in no doubt that Asquith had refused the chancellor's resignation over the

According to Lord Birkenhead, Lloyd George's Liberals were of poor intellect, with no great leaders to take the government onwards. McKenna was certainly a technocrat but did not want to be Prime Minister although he might conceivably have been offered the post. In reality, the Conservatives wanted one of their own. However, he wished to enter Parliament in July 1923 as MP for the

According to Lord Birkenhead, Lloyd George's Liberals were of poor intellect, with no great leaders to take the government onwards. McKenna was certainly a technocrat but did not want to be Prime Minister although he might conceivably have been offered the post. In reality, the Conservatives wanted one of their own. However, he wished to enter Parliament in July 1923 as MP for the

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

politician. His first Cabinet post under Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1 ...

was as President of the Board of Education

The secretary of state for education, also referred to as the education secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the work of the Department for Education. The incumbent is a member of the Ca ...

, after which he served as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. His most important roles were as Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

and Chancellor of the Exchequer during the premiership of H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

. He was studious and meticulous, noted for his attention to detail, but also for being bureaucratic and partisan.

Background and education

Born in Kensington, London, McKenna was the son of William Columban McKenna and his wife Emma, daughter of Charles Hanby. Sir Joseph Neale McKenna was his uncle. McKenna was educated atKing's College School

King's College School, also known as Wimbledon, KCS, King's and KCS Wimbledon, is a public school in Wimbledon, southwest London, England. The school was founded in 1829 by King George IV, as the junior department of King's College London an ...

and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge

Trinity Hall (formally The College or Hall of the Holy Trinity in the University of Cambridge) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

It is the fifth-oldest surviving college of the university, having been founded in 1350 by ...

. At Cambridge he was a notable rower. In 1886, he was a member of the Trinity Hall Boat Club eight that won the Grand Challenge Cup

The Grand Challenge Cup is a rowing competition for men's eights. It is the oldest and best-known event at the annual Henley Royal Regatta on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames in England. It is open to male crews from all eligible rowing ...

at Henley Royal Regatta. He rowed bow in the winning Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

boat in the 1887 Boat Race. Also in 1887 he was a member of the Trinity Hall coxless four

A coxless four is a rowing boat used in the sport of competitive rowing. It is designed for four persons who propel the boat with sweep oars, without a coxswain.

The crew consists of four rowers, each having one oar. There are two rowers on t ...

that won the Stewards' Challenge Cup at Henley.

Political career

McKenna was elected at the 1895 general election asMember of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for North Monmouthshire. McKenna was a Liberal Imperialist. After the Khaki Election of 1900, he favoured the return to government of former Liberal Prime Minister Lord Rosebery

Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, 1st Earl of Midlothian, (7 May 1847 – 21 May 1929) was a British Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from March 1894 to June 1895. Between the death of ...

, although this did not happen.

In December 1905 McKenna was appointed, in preference to

In December 1905 McKenna was appointed, in preference to Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, as Financial Secretary to the Treasury

The financial secretary to the Treasury is a mid-level ministerial post in His Majesty's Treasury. It is nominally the fifth most significant ministerial role within the Treasury after the first lord of the Treasury, the chancellor of the Excheq ...

. He then served in the Liberal Cabinets of Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith as President of the Board of Education

The secretary of state for education, also referred to as the education secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the work of the Department for Education. The incumbent is a member of the Ca ...

, First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

(1908–11), and Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

.

He was considered methodical and efficient, but his opponents thought him priggish, prissy and lacking in charisma. McKenna's estimates were submitted to unprecedented scrutiny by the 'economists' David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

and Churchill. McKenna submitted large naval estimates in December 1906 for the years 1909-10 of £36 m. This was the Dreadnought building programme inspired by naval reformer Admiral Fisher.

In 1907 James Bryce was appointed Ambassador to the US,

In 1907 James Bryce was appointed Ambassador to the US, Augustine Birrell

Augustine Birrell KC (19 January 185020 November 1933) was a British Liberal Party politician, who was Chief Secretary for Ireland from 1907 to 1916. In this post, he was praised for enabling tenant farmers to own their property, and for exte ...

replaced him as Chief Secretary for Ireland, and McKenna succeeded Birrell as President of the Board of Education. He was responsible for such reforms as the introduction of free places in secondary schools and the bestowing upon local authorities the powers to deal with the health and physical needs of children, and was promoted to the cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty only a year later.

First Lord

At the Admiralty McKenna started the Labour Exchange Bill from May 1909, a policy later associated with Churchill, in an effort to relieve unemployment. He was increasingly attacked in speeches outside Parliament. The number of Dreadnoughts to be built was increased from six to eight ships; four initially and four later. Lloyd George and Churchill had attacked McKenna's position in a plan to persuade the Liberal left of the need for defence cuts. Nonetheless McKenna was on the Cabinet finance committee that discussed Lloyd George's budget proposal of 7 March 1910, and on 12 April refused to contemplate the chancellor's proposed defence cuts. He held his seat in the General Elections of 1910, and kept his post at the Admiralty in Asquith's government. McKenna had attended the Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) on 17 December 1908 and 23 March 1909, during which periods he had fully comprehended the gravity of the naval threat. He also attended the famous meeting on 23 August 1911, chaired by the Prime Minister, at which Brigadier-General Wilson, over naval opposition, persuaded ministers to deploy an expeditionary force to France in the event of war. Asquith dismissed the Royal Navy's war plans as "wholly impracticable". McKenna had little support in Cabinet, and Asquith, Richard Haldane, and Churchill wanted the latter to replace him at the Admiralty. Fortunately war was averted despite theAgadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

. On 16 November McKenna accepted the Home Office, swapping jobs with Churchill.

In total McKenna had 'laid the keels' of 18 new battleships that contributed mightily to the British fleet that would fight at the Battle of Jutland in 1916. McKenna commenced the Dreadnought Arms Race: the fundamental strategic basis was for a vast fleet, large enough to intimidate Germany to decline to fight. But in the event Britain's advantage was ephemeral and fleeting.

Peacetime Home Secretary

McKenna accepted his move to the Home Office in October 1911 partly because he had recovered from an appendicitis operation. He was one of numerous Cabinet appointments at the time which, according to historianDuncan Tanner

Duncan Tanner (19 February 1958 – 11 February 2010) was a political historian and academic. His best-known work covered the British Labour Party and voting in the early 20th century. He held the post of director of the Welsh Institute for Social ...

, "pushed the (Liberal) party still further to the left". McKenna and Charles Hobhouse

Sir Charles Edward Henry Hobhouse, 4th Baronet, TD, PC, JP (30 June 1862 – 26 June 1941) was a British Liberal politician and officer in the Territorial Force. He was a member of the Liberal cabinet of H. H. Asquith between 1911 and 191 ...

were responsible for the Welsh Church Disestablishment Bill finally drafted on 20 February 1912. The ''ODNB

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' calls him a wise and judicious Home Secretary. He was stolidly opposed by the Conservative F.E.Smith.

Another piece of legislation ensued in the Coal Mines Bill regulating pay and conditions. McKenna enthusiastically supported the minimum wage bill in principle, but partly to prevent 'civil war' in the coalfields. With Asquith's approval McKenna left a Cabinet meeting, at which he was on the majority side, to attend on the King, having left behind an "admirable memo."

Throughout the summer of 1912 he opposed the escalation of the naval race, occasioned by Churchill's plan to build a new Mediterranean fleet.

He opposed a Temperance Bill. He also made a radical proposal to let prisoners out on short licence, which he sponsored to deal with militant suffragists, a bill unanimously approved by cabinet. On 13 March 1913 he voted against compulsory military training.

At a "council of war" with Lloyd George on 13 June, McKenna was left in no doubt that Asquith had refused the chancellor's resignation over the

On 13 March 1913 he voted against compulsory military training.

At a "council of war" with Lloyd George on 13 June, McKenna was left in no doubt that Asquith had refused the chancellor's resignation over the Marconi scandal

The Marconi scandal was a British political scandal that broke in mid-1912. Allegations were made that highly placed members of the Liberal government under the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith had profited by improper use of information about the go ...

. McKenna himself was categorical as to their innocence of the share dealings. This advice may have saved the Welsh Wizard's career. He made it clear that the Government could not secure any contracts for favours whether from Marconi or Lord Cowdray.

With Irish parentage in his own family, McKenna was happy to support the half-cash, half-stock scheme on 16 July for the Irish Purchase Act introduced by Augustine Birrell, as the prospect for Irish Home Rule drew ever nearer. Dublin was in turmoil, to McKenna and others on the Left ( Walter Runciman, Charles Hobhouse, and John Burns

John Elliot Burns (20 October 1858 – 24 January 1943) was an English trade unionist and politician, particularly associated with London politics and Battersea. He was a socialist and then a Liberal Member of Parliament and Minister. He was ...

) it was as much Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Unionism in Ireland, Irish u ...

's fault as James Larkin

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish Labour Party along with James Connolly and Willia ...

's.

McKenna blamed Churchill for stirring up the Northcliffe press against the cabinet's plans to boost the army's budget by £800,000 and a proposed increase of £6 million in the Royal Navy's bi-annual estimate. In the new year McKenna was one of Lloyd George's group to analyse Churchill's plans for Dreadnought construction; they insisted that expenditure must be reduced to that of 1912–13.

In late January 1914 his friends Charles Hobhouse and Sir John Simon

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954), was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. He is one of only three peop ...

agreed to lobby the Chancellor. The following day at the Treasury their "entire sitting was taken up" by the group's tirade against Churchill's management of the Admiralty. They retired the next morning to Smith Square to discuss the Home Rule crisis in Ireland; a dissolution "would be a complete practical triumph for the Tory Party", wrote Hobhouse; their group was expanded to include Beauchamp and Runciman. On 29 January the group sent a petition to Asquith protesting against the Naval Estimates, now assumed to total £52.5 million.

McKenna had been receiving messages of grave concern from Irish leader John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from ...

. On 17 July, before the weekend, McKenna proposed an Amending Bill to the Government of Ireland Bill to allow any Ulster county to opt out of Home Rule.

Wartime Home Secretary

The problems of Ireland paled into insignificance in early August. Broadly-speaking McKenna, an Asquithian, supported the pledge to go to war to defend Belgium's neutrality, but he did not want to send the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).Charles Masterman

Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman Privy Council of the United Kingdom, PC (24 October 1873 – 17 November 1927) was a British radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician, intellectual and man of letters. He worked closely with such ...

, Runciman and McKenna all wanted to stall the Kaiser for invaluable time. Most of the cabinet opposed armed intervention in France, almost up until the declaration of war.

The Home Secretary remained in charge of State Security: more than 6,000 espionage cases were investigated, none of which produced any traitors. The smuggling of German arms during the Irish Home Rule Crisis

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1912. Unionists in Ulster, d ...

had sparked fears that Britain was infiltrated by a network of spies. In response cable telegraphs were laid from Dartmouth to Brest in Brittany to guarantee Allied communications links. On 20 October a warrant went out for the arrest of 23,000 Germanic aliens, and food supplies to Belgium were cut lest they fell into German hands. McKenna refused to allow the publication of the sinking of HMS ''Audacious''; in the event it was 'leaked' to ''The Evening News'' anyway. And on 30 October the Cabinet announced a general policy of censorship. In the ''Wilhelmina'' case he again referred to the legal situation, seeking a solution in international law.

McKenna disliked the autocratic and dismissive Lord Kitchener, appointed Secretary of State for War at the start of the war. Immediately on his appointment their relations soured: the policy of voluntary recruitment continued as the Army needed one million men, until the Adjutant-General complained there were too many new recruits. On 5 March 1915 McKenna reported that the Ritz Carlton Hotel, New York was being used as a spy network to inform on British intelligence; the government, determined to prevent the USA entering the war on Germany's side, informed Washington. McKenna supported Asquith and gradually fell out with Lloyd George.

Internal wrangling in Cabinet conversations reached fever pitch: Edwin Montagu

Edwin Samuel Montagu PC (6 February 1879 – 15 November 1924) was a British Liberal politician who served as Secretary of State for India between 1917 and 1922. Montagu was a "radical" Liberal and the third practising Jew (after Sir Herbe ...

, a cousin of Herbert Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel, (6 November 1870 – 5 February 1963) was a British Liberal politician who was the party leader from 1931 to 1935.

He was the first nominally-practising Jew to serve as a Cabinet minister and to be ...

and ally of Lloyd George suggested that Asquith was jealous of Sir Edward Grey's prowess in the Foreign Office. When in April 1915 the Home Secretary banned Montagu from his home for six months, the scene was set for a final split in the party. McKenna was a Teetotaller, something he had impressed upon the King was necessary for good government. His Majesty "took the pledge" for the duration of the war, an example which Lord Chancellor Haldane felt he had to follow for the remainder of his time in office. McKenna's asceticism won few new friends, so that when the end came for his career it was both dramatic and complete.

Asquith's Liberal Chancellor

In May 1915 Asquith formed a coalition government. McKenna, a reluctant coalitionist, became Chancellor of the Exchequer. In the meantime, McKenna oversaw the issue of the SecondWar Loan

War bonds (sometimes referred to as Victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an unpopular level. They are ...

in June 1915, at an interest rate of 4.5%, although his first budget was actually on 21 September 1915 was a serious attempt to deal with an impending debt crisis. Revenues were rising, but not by enough to cover the £1.6 billion government expenditure. McKenna increased income tax rates and introduced a 50% excess profit tax, and increases in indirect taxation of goods such as tea, coffee, and tobacco. Post Office charge increases could not be included in the Budget (as they would have endangered its status as a money bill), and were instead introduced in a Post Office and Telegraph Bill.

McKenna duties

In September 1915 he introduced a 33% levy on luxury imports in order to fund the war effort. The McKenna duties applied to cinematographic film; clocks and watches; motorcars and motorcycles; and musical instruments. The duties were revoked by Ramsay MacDonald's short-lived Labour government in 1924, only to be reimposed in 1925.Fiscal relations and Lloyd George

The April 1916 budget saw further large rises in income and excess profit taxes, at a time when prices of basic food commodities were rising. Sales taxes were extended to rail tickets, mineral water, cider and perry, and entertainments. The government pledged that if they issued War Loan at the even higher interest (as they did with the 5% issue of 1917), holders of the 4.5% bonds might also convert to the new rate. His predecessorDavid Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

criticised McKenna in his memoirs for increasing the interest rate from 3.5% on the 1914 War Loan at a time when investors had few alternatives and might even have had their capital "conscripted" by the government. Not only did the change ultimately increase the nation's interest payments by £100 million/year but it meant rates were higher throughout the economy during the post-war depression. Compared with France, the British government relied more on short-term financing in the form of treasury bills and exchequer bonds during World War I; Treasury bills provided the bulk of British government funds in 1916. McKenna fell out with Lord Cunliffe, Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent grooming their successor. The governor of the Ba ...

. Furthermore, he tried to sequestrate the assets of the US Prudential Assurance Company to pay for American war ''materiel'' purchases.

An opponent of Lloyd George, McKenna was critical of the Prime Minister's political approach, telling Conservative politician Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the ...

that "you disagree with us, but you can understand our principles. Lloyd George doesn't understand them and we can't make him". But unlike McKenna, Lloyd George had no problem with relations with Cunliffe.

McKenna nevertheless saw the state as having an important role in society, a sentiment that he shared with Asquith. As noted by his biographer and nephew, Stephen McKenna,

Without trying to define the whole duty of Liberal man, Asquith and McKenna were at one in seeing that if certain services were not undertaken by the state, they would not be undertaken at all. Old age pensions were a case in point. They had not been dangled as an electioneering bait; Asquith made no appeal to sentiment or emotion when the Cabinet committee of investigation was set up, but from their first days together at the Treasury he and McKenna had agreed that, if the money could be found, this was a matter on which a beginning must be made forthwith.

Conscription

The issue of enforced service in the armed forces was controversial in Britain. The Conservatives were almost entirely in favour, but the Liberals were split, with Asquithians largely opposed on libertarian grounds, whilst Lloyd George united with the Tories in what he declared to be a vital national interest. Sir John Simon, Liberal Home Secretary and an ally of McKenna, resigned over the conscription of bachelors in January 1916. As Chancellor of Exchequer McKenna objected to the conscription of married men in May 1916 on purely economic grounds, arguing that it would 'deplete' Britain's war industries. McKenna knew that for Asquith to remain in office he had to move towards conscription, whether he liked it or not; if he did not, the Tories would topple the government. At a decisive meeting on 4 December 1916 McKenna tried to persuade Asquith to sack Lloyd George to save the government. McKenna retired into opposition upon the fall of Asquith at the end of 1916.Chairman of the Midland Bank

He lost his seat in the 1918 general election and became a non-executive member of the board of theMidland Bank

Midland Bank Plc was one of the Big Four banking groups in the United Kingdom for most of the 20th century. It is now part of HSBC. The bank was founded as the Birmingham and Midland Bank in Union Street, Birmingham, England in August 1836. It ...

at the invitation of the chairman, Liberal MP Sir Edward Holden. Before Holden died in 1919, McKenna had sat in his office every day to observe the activities of a chairman. An elaborate coda was drafted to allow the bank's directors to determine whether he should resign his Pontypool seat where he was presently the Liberal candidate (his previous seat of North Monmouthshire had disappeared in boundary changes). But the situation did not arise as he was not elected in 1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éireann, the day after Éamon de Valera ...

. The new Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Bonar Law hoped to persuade him to come out of retirement and serve once again at the Exchequer in a Conservative Cabinet, but he refused, and remained in private life. His refusal was partly because he wanted to promote an alliance between Bonar Law and Asquith, who was still official leader of the Liberal Party. The following year Bonar Law's successor Stanley Baldwin repeated the request and McKenna was more agreeable, but again declined.

McKenna used his status as chairman of one of the big five British banks to argue that monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

could be used to achieve domestic macroeconomic objectives. At the Chamberlain-Bradbury committee he questioned whether a return to the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

was desirable. John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

was the only other witness to do so, although others proposed a delayed return.

Possible return to government

According to Lord Birkenhead, Lloyd George's Liberals were of poor intellect, with no great leaders to take the government onwards. McKenna was certainly a technocrat but did not want to be Prime Minister although he might conceivably have been offered the post. In reality, the Conservatives wanted one of their own. However, he wished to enter Parliament in July 1923 as MP for the

According to Lord Birkenhead, Lloyd George's Liberals were of poor intellect, with no great leaders to take the government onwards. McKenna was certainly a technocrat but did not want to be Prime Minister although he might conceivably have been offered the post. In reality, the Conservatives wanted one of their own. However, he wished to enter Parliament in July 1923 as MP for the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, and neither of the incumbent MPs would agree to vacate in order to make room. As a result, McKenna declined, as he had no wish to vacate the bank. McKenna continued to write economic reports for Whitehall and Westminster, but by August 1923, his political career had come to an end.

The lasting impression was one of the pin-striped merchant banker, a model of precision but not a clubbable leader of men; his absence from London society and Brooks's

Brooks's is a gentlemen's club in St James's Street, London. It is one of the oldest and most exclusive gentlemen's clubs in the world.

History

In January 1762, a private society was established at 50 Pall Mall by Messrs. Boothby and James ...

seemed to imply retirement. However, his financial reputation was such as to prompt Stanley Baldwin to demand his return to government in the 1930s. As late as 1939, it was proposed that he should be brought back to replace Liberal National Chancellor Sir John Simon. McKenna was the last of the Asquithians to die, in 1943.

Family

McKenna was married in 1908 to Pamela Jekyll (who died November 1943), younger daughter of Sir Herbert Jekyll (brother of landscape gardener Gertrude Jekyll) and his wife Dame Agnes Jekyll, née Graham. They had two sons – Michael (died 1931) and David, who married Lady Cecilia Elizabeth Keppel (12 April 1910 – 16 June 2003), a daughter ofWalter Keppel, 9th Earl of Albemarle

Walter Egerton George Lucian Keppel, 9th Earl of Albemarle, (28 February 1882 – 14 July 1979) was a British nobleman and soldier, styled Viscount Bury from 1894 to 1942.

Life

Keppel was the eldest son of Arnold Keppel, 8th Earl of Albemarle, a ...

in 1934. McKenna was a talented financier, and a champion bridge player in his free time. In royal company at Balmoral McKenna played golf.

Reginald McKenna died in London on 6 September 1943, and was buried at St Andrew's Church in Mells, Somerset. His wife died two months later, and is buried beside him. McKenna was a regular client of Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memoria ...

who designed the Midland Bank headquarters in Poultry, London

Poultry (formerly also Poultrey) is a short street in the City of London, which is the historic nucleus and modern financial centre of London. It is an eastern continuation of Cheapside, between Old Jewry and Mansion House Street, towards Bank ...

, and several branches. Pamela McKenna was a high society hostess whose dinner parties charmed Asquith at their Lutyens-built townhouse in Smith Square

Smith Square is a square in Westminster, London, 250 metres south-southwest of the Palace of Westminster. Most of its garden interior is filled by St John's, Smith Square, a Baroque surplus church, which has inside converted to a concert hall ...

. Lutyens the unofficial imperial-government architect built several homes for McKenna, and the political classes, as well as his grave. Lutyens was commissioned to build 36 Smith Square in 1911, followed by Park House in Mells Park, Somerset, built in 1925. The owners of Mells Park were Sir John Horner and his wife Frances

Frances is a French and English given name of Latin origin. In Latin the meaning of the name Frances is 'from France' or 'free one.' The male version of the name in English is Francis. The original Franciscus, meaning "Frenchman", comes from the F ...

, née Graham, who was Agnes Jekyll's sister, and they agreed to let the park to McKenna for a nominal rent, on the understanding that he would rebuild the house. Lutyens built a final house for McKenna at Halnaker Park, in Halnaker, Sussex, in 1938. Lutyens designed the McKenna family tomb in St Andrew's Church, Mells

St Andrew's Church is a Church of England parish church located in the village of Mells in the English county of Somerset. The church is a grade I listed building.

History

The current church predominantly dates from the late 15th century ...

, in 1932.

His nephew Stephen McKenna was a popular novelist who published a biography of his uncle in 1948.

Publications

* (1928) ''Post-War Banking Policy: A Series of Addresses'' London: William Heinemann.See also

*List of Cambridge University Boat Race crews

This is a list of the Cambridge University crews who have competed in The Boat Race since its inception in 1829.

Rowers are listed left to right in boat position from bow to stroke. The number following the rower indicates the rower's weight ...

* Liberal Government 1905-15

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * held atChurchill Archives Centre

The Churchill Archives Centre (CAC) at Churchill College at the University of Cambridge is one of the largest repositories in the United Kingdom for the preservation and study of modern personal papers. It is best known for housing the papers of ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:McKenna, Reginald

1863 births

1943 deaths

People educated at King's College School, London

Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

Cambridge University Boat Club rowers

Liberal Party (UK) MPs for Welsh constituencies

British people of Irish descent

British Secretaries of State

British Secretaries of State for Education

Chancellors of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom

Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

UK MPs 1895–1900

UK MPs 1900–1906

UK MPs 1906–1910

UK MPs 1910

UK MPs 1910–1918

First Lords of the Admiralty

Place of birth missing