Reformation in Ireland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Reformation in Ireland was a movement for the reform of religious life and institutions that was introduced into Ireland by the English administration at the behest of King Henry VIII of England. His desire for an annulment of his marriage was known as the

The dissolutions in Ireland followed a very different course from those in England and Wales. There were around 400 religious houses in Ireland in 1530—many more, relative to population and material wealth than in England and Wales. In marked distinction to the situation in England, in Ireland the houses of friars had flourished in the 15th century, attracting popular support and financial endowments, undertaking many ambitious building schemes, and maintaining a regular conventual and spiritual life. They constituted around half of the total number of religious houses. Irish monasteries, by contrast, had experienced a catastrophic decline in numbers, such that by the 16th century, it appears that only a minority maintained the daily religious observance of the Divine Office. Henry's direct authority, as Lord of Ireland, and from 1541 as King of Ireland, only extended to the area of the Pale immediately around Dublin. From the late 1530s his administrators temporarily succeeded in persuading some clan chiefs to adopt his policy of

The dissolutions in Ireland followed a very different course from those in England and Wales. There were around 400 religious houses in Ireland in 1530—many more, relative to population and material wealth than in England and Wales. In marked distinction to the situation in England, in Ireland the houses of friars had flourished in the 15th century, attracting popular support and financial endowments, undertaking many ambitious building schemes, and maintaining a regular conventual and spiritual life. They constituted around half of the total number of religious houses. Irish monasteries, by contrast, had experienced a catastrophic decline in numbers, such that by the 16th century, it appears that only a minority maintained the daily religious observance of the Divine Office. Henry's direct authority, as Lord of Ireland, and from 1541 as King of Ireland, only extended to the area of the Pale immediately around Dublin. From the late 1530s his administrators temporarily succeeded in persuading some clan chiefs to adopt his policy of

Henry's and Edward's efforts were then reversed by Queen Mary I of England (1553–1558), who had always been Roman Catholic. On her ascent to the throne, Mary reimposed orthodox Roman Catholicism by the First and Second Statute of Repeal of 1553 and 1555. When some Episcopal sees in Ireland became vacant, clerics loyal to Rome were chosen by Mary, with the approval of the Pope. In other cases, bishops in possession of dioceses that had been appointed by her father, without the approval of the Pope, were deposed.

She arranged for the

Henry's and Edward's efforts were then reversed by Queen Mary I of England (1553–1558), who had always been Roman Catholic. On her ascent to the throne, Mary reimposed orthodox Roman Catholicism by the First and Second Statute of Repeal of 1553 and 1555. When some Episcopal sees in Ireland became vacant, clerics loyal to Rome were chosen by Mary, with the approval of the Pope. In other cases, bishops in possession of dioceses that had been appointed by her father, without the approval of the Pope, were deposed.

She arranged for the

/ref> The

Why the Reformation failed in Ireland

by

King's Great Matter

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until ...

. Ultimately Pope Clement VII refused the petition; consequently, in order to give legal effect to his wishes, it became necessary for the King to assert his lordship over the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in his realm. In passing the Acts of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the Eng ...

in 1534, the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

confirmed the King's supremacy over the Church in the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, ...

. This challenge to Papal supremacy resulted in a breach with the Catholic Church. By 1541, the Irish Parliament had agreed to the change in status of the country from that of a Lordship

A lordship is a territory held by a lord. It was a landed estate that served as the lowest administrative and judicial unit in rural areas. It originated as a unit under the feudal system during the Middle Ages. In a lordship, the functions of econ ...

to that of Kingdom of Ireland.

Unlike similar movements for religious reform on the continent of Europe, the various phases of the English Reformation as it developed in Ireland were largely driven by changes in government policy, to which public opinion in England gradually accommodated itself. In Ireland, however, the government's policy was not embraced by public opinion; the majority of the population continued to adhere to Roman Catholicism.

Religious policy of Henry VIII

Norman and English monarchs used the title "Lord of Ireland" to refer to their Irish conquests dating from the Norman invasion of Ireland. In passing theCrown of Ireland Act 1542

The Crown of Ireland Act 1542 is an Act passed by the Parliament of Ireland (33 Hen. 8 c. 1) on 18 June 1542, which created the title of King of Ireland for King Henry VIII of England and his successors, who previously ruled the island as Lor ...

, the Irish Parliament granted Henry, by his command, a new title – King of Ireland. The state was renamed the Kingdom of Ireland. The King desired this innovation because the Lordship of Ireland had been granted by the Papacy; technically, he held the Lordship in fief from the Pope. As Henry had been excommunicated in 1533 and again in 1538, he worried that his title could be withdrawn by his overlord – the Pope.

Henry also arranged for the Irish Parliament to declare him the head of the "Church in Ireland". The main instrument of state power in the establishment of the state church in the new Kingdom of Ireland was the Archbishop of Dublin, George Brown. He was appointed by the King upon the death of the incumbent, though without the approval of the Pope. The Archbishop arrived in Ireland in 1536. The reforms were continued by Henry's successor – Edward VI of England. The Church of Ireland claims Apostolic succession because of the continuity in the hierarchy; however this claim is disputed by the Roman Catholic Church, which asserts, in Apostolicae curae

''Apostolicae curae'' is the title of a papal bull, issued in 1896 by Pope Leo XIII, declaring all Anglican ordinations to be "absolutely null and utterly void". The Anglican Communion made no official reply, but the archbishops of Canterbury ...

, that Anglican Orders are invalid.

Henry's sanctions on outspoken Catholics and Lutherans differed; Catholics loyal to the Holy See were to be prosecuted as traitors, while Lutherans, much rarer in Ireland, were to be burned at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

as heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. He promulgated the Six Articles Act in 1539.

Henry died in 1547. In his reign, prayers remained the same, with the Latin Breviary still used until the Book of Common Prayer (in English) was introduced from 1549. From 1548, for the first time, Irish Communicants were given wine and bread; the former Roman Rite of the Mass allowed a congregation to be given bread only, with wine taken by the priest.

Dissolution of the monasteries

The dissolutions in Ireland followed a very different course from those in England and Wales. There were around 400 religious houses in Ireland in 1530—many more, relative to population and material wealth than in England and Wales. In marked distinction to the situation in England, in Ireland the houses of friars had flourished in the 15th century, attracting popular support and financial endowments, undertaking many ambitious building schemes, and maintaining a regular conventual and spiritual life. They constituted around half of the total number of religious houses. Irish monasteries, by contrast, had experienced a catastrophic decline in numbers, such that by the 16th century, it appears that only a minority maintained the daily religious observance of the Divine Office. Henry's direct authority, as Lord of Ireland, and from 1541 as King of Ireland, only extended to the area of the Pale immediately around Dublin. From the late 1530s his administrators temporarily succeeded in persuading some clan chiefs to adopt his policy of

The dissolutions in Ireland followed a very different course from those in England and Wales. There were around 400 religious houses in Ireland in 1530—many more, relative to population and material wealth than in England and Wales. In marked distinction to the situation in England, in Ireland the houses of friars had flourished in the 15th century, attracting popular support and financial endowments, undertaking many ambitious building schemes, and maintaining a regular conventual and spiritual life. They constituted around half of the total number of religious houses. Irish monasteries, by contrast, had experienced a catastrophic decline in numbers, such that by the 16th century, it appears that only a minority maintained the daily religious observance of the Divine Office. Henry's direct authority, as Lord of Ireland, and from 1541 as King of Ireland, only extended to the area of the Pale immediately around Dublin. From the late 1530s his administrators temporarily succeeded in persuading some clan chiefs to adopt his policy of surrender and regrant

During the Tudor conquest of Ireland (c.1540–1603), "surrender and regrant" was the legal mechanism by which Irish clans were to be converted from a power structure rooted in clan and kin loyalties, to a late-feudal system under the English l ...

, including the adoption of his state religion.

Nevertheless, Henry was determined to carry through a policy of dissolution in Ireland – and in 1537 introduced legislation into the Irish Parliament to legalise the closure of monasteries. The process faced considerable opposition, and only sixteen houses were suppressed. Henry remained resolute however, and from 1541 as part of the Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, ...

, he continued to press for the area of successful dissolution to be extended. For the most part, this involved making deals with local lords, under which monastic property was granted away in exchange for oaths of allegiance to the new Irish Crown; and consequently Henry acquired little if any of the wealth of the Irish houses. By the time of Henry's death (1547) around half of the Irish monastic houses had been suppressed; but many houses of friars continued to resist dissolution until well into the reign of Elizabeth I.

Bishoprics

During the English Reformation, the Church of Ireland suffered in its temporal affairs:"more than half the clerical property in the kingdom being vested in lay hands; but that of Ireland was in a manner annihilated. Bishopricks, colleges, glebes and tithes were divided without mercy amongst the great men of the time, or leased out on small rents for ever to the friends and relations of the incumbents. Many Irish bishopricks never recovered this devastation, as Aghadoe, Kilfenora and others. The Bishoprick of Ferns was left not worth one shilling. Killala, the best in Ireland, was worth only 300l. per annum; Clonfert, 200l.; the Archbishoprick of Cashel, 100l.; Waterford, 100l.; Cork, only 70l.; Ardagh, 1l. 1s. 8d.; and the rest at even a lower rate."

Religious policy of Edward VI

Henry's son Edward VI of England (1547–53) formally establishedProtestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

as the state religion, which was as much a religious matter as his father's reformation had been political. His reign only lasted for six years and his principal reform, the Act of Uniformity 1549, had much less impact in Ireland than in England. He abolished the crime of heresy in 1547.

During his reign attempts were made to introduce Protestant liturgy and bishops to Ireland. These attempts were met with hostility from within the Church, even by those who had previously conformed. In 1551, a printing press was established in Dublin which printed a Book of Common Prayer in English.

Religious policy of Queen Mary I

Henry's and Edward's efforts were then reversed by Queen Mary I of England (1553–1558), who had always been Roman Catholic. On her ascent to the throne, Mary reimposed orthodox Roman Catholicism by the First and Second Statute of Repeal of 1553 and 1555. When some Episcopal sees in Ireland became vacant, clerics loyal to Rome were chosen by Mary, with the approval of the Pope. In other cases, bishops in possession of dioceses that had been appointed by her father, without the approval of the Pope, were deposed.

She arranged for the

Henry's and Edward's efforts were then reversed by Queen Mary I of England (1553–1558), who had always been Roman Catholic. On her ascent to the throne, Mary reimposed orthodox Roman Catholicism by the First and Second Statute of Repeal of 1553 and 1555. When some Episcopal sees in Ireland became vacant, clerics loyal to Rome were chosen by Mary, with the approval of the Pope. In other cases, bishops in possession of dioceses that had been appointed by her father, without the approval of the Pope, were deposed.

She arranged for the Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the En ...

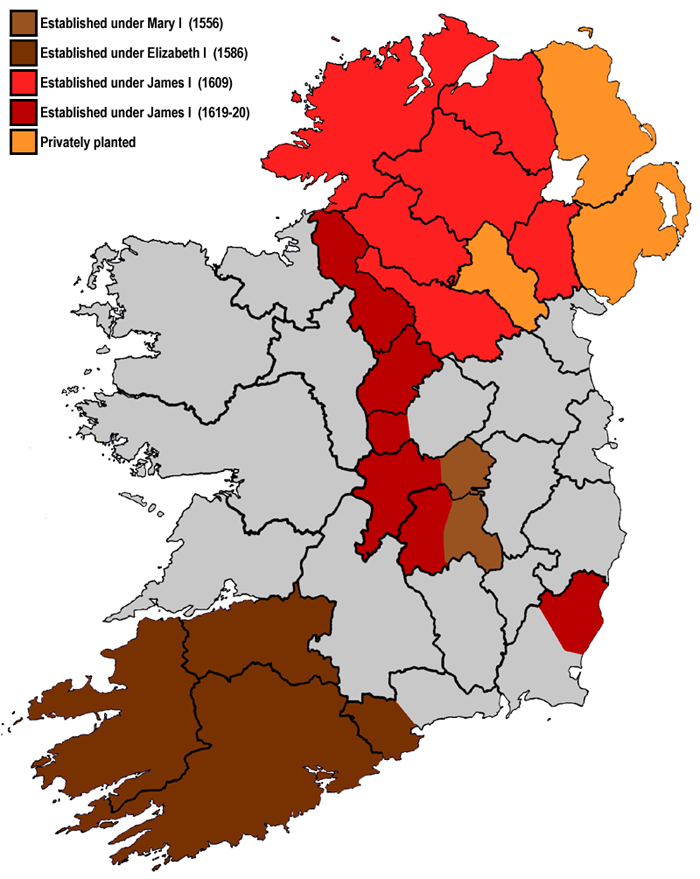

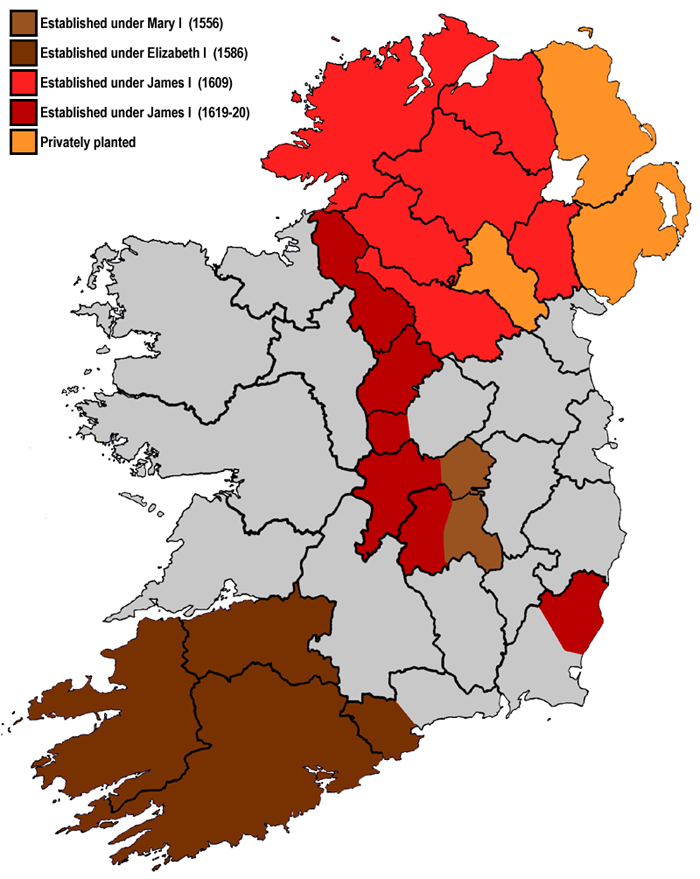

(which asserted England's independence from papal authority) to be repealed in 1554, and also revived the Heresy Acts. In turn it was agreed that the former monasteries would stay dissolved, so as to preserve the loyalty of those who had sinfully bought monastic lands, by an Act passed in January 1555 and the agreement of Pope Julius III. In Ireland Mary started the first planned wholesale plantations of settlers from England that, ironically, soon came to be associated with Protestantism.

In 1554 she married Philip, Prince of Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the throne of Spain. According to the Spanish Constitution ...

, who in 1558 became the King of Spain. Philip and Mary were also granted a papal bull in 1555 by Pope Paul IV to reconfirm their status as the Catholic King and Queen of the new Kingdom of Ireland.

Also in 1555 the Peace of Augsburg established the principle of '' Cuius regio, eius religio'', requiring Christians to follow their ruler's version of Christianity, and it must have seemed that the experiment of reformation had ended.

Religious policy of Queen Elizabeth I

Mary's Protestant half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I succeeded in having Parliament pass another Act of Supremacy in 1559. The Act of 1534 had declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the Pope. Any act of allegiance to the Papacy was considered treasonous because the Papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. Additionally, the Irish Act of Uniformity, passed in 1560, made worship in churches adhering to the Church of Ireland compulsory. Anyone who took office in the Irish church or government was required to take the Oath of Supremacy; penalties for violating it included hanging and quartering. Attendance at Church of Ireland services became obligatory – those who refused to attend, whether Roman Catholics or Protestant nonconformists, could be fined and physically punished asrecusant

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

s by the civil powers. Initially Elizabeth tolerated non-Anglican observance, but after the promulgation in 1570 of the Papal Bull, ''Regnans in Excelsis

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime", declared h ...

'', Roman Catholics were increasingly seen as a threat to the security of the state. Nevertheless, the enforcement of conformity in Ireland was sporadic and limited for much of the sixteenth century.

The issue of religious and political rivalry continued during the two Desmond Rebellions (1569–83) and the Nine Years' War (1594–1603), both of which overlapped with the Anglo-Spanish War, during which some rebellious Irish nobles were helped by the Papacy and by Elizabeth's arch-enemy Philip II of Spain. Due to the unsettled state of the country Protestantism made little progress, unlike in Celtic Scotland and Wales at that time. It came to be associated with military conquest and colonisation and was therefore hated by many. The political-religious overlap was personified by Adam Loftus, who served as Archbishop and as Lord Chancellor of Ireland.

The bulk of Protestants in Ireland during Elizabeth's reign were confined to the ranks of new settlers and government officials, who formed a small minority. Amongst the native Gael

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

ic Irish and Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

, recusancy

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

pre-dominated and was tolerated by Elizabeth for fear of alienating the Old English further. To them, the official state religion had already changed several times since 1533, and might well change again, as Elizabeth's heir until 1587 was the Roman Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots.

Elizabeth established Trinity College, Dublin in 1592, partly in order to train clergy to preach the reformed faith. In 1571 a Gaelic printing typeface was created and brought to Ireland by dignitaries of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, to print documents in the Irish language for the purposes of evangelisation. The liturgy that was intended to be printed was to be used for the preaching in Irish in specially appointed churches in the main town of every diocese. The first translation of the New Testament into Irish was done in 1603, and a translation of the Gospels was sponsored by Richard Boyle.

Religious policy of King James I

The reign of James I (1603–25) started tolerantly, and theTreaty of London (1604)

The Treaty of London, signed on 18 August O.S. (28 August N.S.) 1604, concluded the nineteen-year Anglo-Spanish War. The treaty restored the ''status quo'' between the two nations. The negotiations probably took place at Somerset House in ...

was signed with Spain, but the Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who sough ...

in 1605 caused him and his officials to adopt a harder line against Roman Catholics who remained in the majority, even in the Irish House of Lords

The Irish House of Lords was the upper house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from medieval times until 1800. It was also the final court of appeal of the Kingdom of Ireland.

It was modelled on the House of Lords of England, with membe ...

. So few had converted to Protestantism that the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation was introduced in 1612, much later than in the rest of Europe, typically marked by the Council of Trent, convened in 1545.Counter-Reformation, britannica.com/ref> The

Flight of the Earls

The Flight of the Earls ( ir, Imeacht na nIarlaí)In Irish, the neutral term ''Imeacht'' is usually used i.e. the ''Departure of the Earls''. The term 'Flight' is translated 'Teitheadh na nIarlaí' and is sometimes seen. took place in Se ...

in 1607 led on to the Plantation of Ulster, but many of the new settlers were Presbyterian and not Anglican; reformed, but not entirely acceptable to the Dublin administration. The settlers allowed James to create a slight Protestant majority in the Irish House of Commons

The Irish House of Commons was the lower house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from 1297 until 1800. The upper house was the House of Lords. The membership of the House of Commons was directly elected, but on a highly restrictive fran ...

in 1613.

The work of translating the Old Testament into Irish for the first time was undertaken by William Bedell

The Rt. Rev. William Bedell, D.D. ( ga, Uilliam Beidil; 15717 February 1642), was an Anglican churchman who served as Lord Bishop of Kilmore, as well as Provost of Trinity College Dublin.

Early life

He was born at Black Notley in Essex, and ...

(1573–1642), Bishop of Kilmore, who completed his translation within the reign of Charles I, although it was not published until 1680 in a revised version by Narcissus Marsh

Narcissus Marsh (20 December 1638 – 2 November 1713) was an English clergyman who was successively Church of Ireland Bishop of Ferns and Leighlin, Archbishop of Cashel, Archbishop of Dublin and Archbishop of Armagh.

Marsh was born at Hannin ...

(1638–1713), Archbishop of Dublin. Bedell had undertaken a translation of the Book of Common Prayer published in 1606.

In 1631 the Primate James Ussher

James Ussher (or Usher; 4 January 1581 – 21 March 1656) was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland between 1625 and 1656. He was a prolific scholar and church leader, who today is most famous for his ident ...

published "''A Discourse of the Religion Anciently professed by the Irish and Brittish''", arguing that the earlier forms of Irish Christianity were self-governing, and were not subject to control by the Papacy.Ussher, James; A Discourse etc.; London, "RY" 1631 Ussher is more famous for calculating from the Bible that the earth was created on 22 October 4004 BCE.

Policies of Commonwealth and Restoration regimes

The final stage was marked by the Irish Rebellion of 1641 by those groups of theIrish nobility

The Irish nobility could be described as including persons who do, or historically did, fall into one or more of the following categories of nobility:

* Gaelic nobility of Ireland descendants in the male line of at least one historical grade o ...

that continued in their loyalty to the crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

, Roman Catholicism or both. The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649–53 briefly introduced Puritanism

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

as the state religion. The Restoration period that followed and the brief reign of the Roman Catholic James II were characterised by unusual state tolerance for religions in their kingdoms. During the Patriot Parliament of 1689, James II, while remaining Catholic, also refused to abolish his position as head of the Church of Ireland, so ensuring that Protestant bishops attended its sessions.

In the Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691; ga, Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"), was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called th ...

that followed, absolutism was destroyed but the majority of the population felt more conquered than ever. The Irish parliament introduced a series of " Penal Laws" with the ostensible purpose of displacing Roman Catholicism as the majority religion. However, there was no consistent attempt by the Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

to actively convert the bulk of the population to Anglicanism, which suggests that their main purposes were economic – to transfer wealth from Roman Catholic hands to Protestant hands, and to persuade Catholic property owners to convert to Protestantism.

An Irish translation of the revised Book of Common Prayer of 1662 was effected by John Richardson (1664–1747), and was published in 1712.

Despite the Reformation's association with military conquest, the country produced outstanding philosophers who were Anglican Irish philosophers and writers, some of whom were Church of Ireland clergy, such as James Ussher

James Ussher (or Usher; 4 January 1581 – 21 March 1656) was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland between 1625 and 1656. He was a prolific scholar and church leader, who today is most famous for his ident ...

, Archbishop of Dublin; Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dubl ...

, priest; John Toland, essayist, philosopher and free thinker; George Berkeley, bishop. The Presbyterian philosopher Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) had a notable impact in Colonial America.

See also

*Second Reformation

The Second Reformation was an evangelical campaign from the 1820s onwards, organised by theological conservatives in the Church of Ireland and Church of England.

History

Evangelical clergymen were known as "Biblicals" or "New Reformers". The Sec ...

* History of Ireland (1536–1691)

* Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

* Protestantism in Ireland

References

Bibliography

* Blaney, Roger; ''Presbyterians and the Irish Language''. Ulster Historical Foundation, 2012. . * Connolly, S.J.; ''Oxford Companion to Irish History''. Oxford University Press, 2007. . * * Duffy, Seán; ''Medieval Ireland An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. . * Duffy, Seán; ''The Concise History of Ireland''. Gill & Macmillan, 2005. . * *Why the Reformation failed in Ireland

by

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pre ...

{{Kingdom of Ireland

Religion and politics

English Reformation

History of Christianity in Ireland

Anti-Catholicism in Ireland

Anti-Catholicism in Northern Ireland

Anti-Catholicism in England