Red rail on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The red rail (''Aphanapteryx bonasia'') is an extinct species of

The name ''Apterornis'' had already been used for a different extinct bird genus from

The name ''Apterornis'' had already been used for a different extinct bird genus from

Apart from being a close relative of the

Apart from being a close relative of the

From the subfossil bones, illustrations and descriptions, it is known that the red rail was a flightless bird, somewhat larger than a chicken. Subfossil specimens range in size, which may indicate

From the subfossil bones, illustrations and descriptions, it is known that the red rail was a flightless bird, somewhat larger than a chicken. Subfossil specimens range in size, which may indicate

Mundy visited Mauritius in 1638 and described the red rail as follows:

Another English traveller, John Marshall, described the bird as follows in 1668:

Mundy visited Mauritius in 1638 and described the red rail as follows:

Another English traveller, John Marshall, described the bird as follows in 1668:

The two most realistic contemporary depictions of red rails, the Hoefnagel painting from ca. 1610 and the sketches from the ''Gelderland'' ship's journal from 1601 attributed to Laerle, where brought to attention in the 19th century. Much information about the bird's appearance comes from Hoefnagel's painting, based on a bird in the menagerie of

The two most realistic contemporary depictions of red rails, the Hoefnagel painting from ca. 1610 and the sketches from the ''Gelderland'' ship's journal from 1601 attributed to Laerle, where brought to attention in the 19th century. Much information about the bird's appearance comes from Hoefnagel's painting, based on a bird in the menagerie of  The red rail depicted in the ''Gelderland'' journal appears to have been stunned or killed, and the sketch is the earliest record of the species. It is the only illustration of the species drawn on Mauritius, and according to Hume, the most accurate depiction. The image was sketched with pencil and finished in ink, but details such as a deeper beak and the shoulder of the wing are only seen in the underlying sketch. In addition, there are three rather crude black-and-white sketches, but differences in them were enough for some authors to suggest that each image depicted a distinct species, leading to the creation of several scientific names which are now synonyms. An illustration in van den Broecke's 1646 account (based on his stay on Mauritius in 1617) shows a red rail next to a dodo and a one-horned goat, but is not referenced in the text. An illustration in Herbert's 1634 account (based on his stay in 1629) shows a red rail between a broad-billed parrot and a dodo, and has been referred to as "extremely crude" by Hume. Mundy's 1638 illustration was published in 1919.

As suggested by Greenway, there are also depictions of what appears to be a red rail in three of the Dutch artist

The red rail depicted in the ''Gelderland'' journal appears to have been stunned or killed, and the sketch is the earliest record of the species. It is the only illustration of the species drawn on Mauritius, and according to Hume, the most accurate depiction. The image was sketched with pencil and finished in ink, but details such as a deeper beak and the shoulder of the wing are only seen in the underlying sketch. In addition, there are three rather crude black-and-white sketches, but differences in them were enough for some authors to suggest that each image depicted a distinct species, leading to the creation of several scientific names which are now synonyms. An illustration in van den Broecke's 1646 account (based on his stay on Mauritius in 1617) shows a red rail next to a dodo and a one-horned goat, but is not referenced in the text. An illustration in Herbert's 1634 account (based on his stay in 1629) shows a red rail between a broad-billed parrot and a dodo, and has been referred to as "extremely crude" by Hume. Mundy's 1638 illustration was published in 1919.

As suggested by Greenway, there are also depictions of what appears to be a red rail in three of the Dutch artist

Contemporary accounts are repetitive and do not shed much light on the life history of the red rail. Based on fossil localities, the bird widely occurred on Mauritius, in montane, lowland, and coastal habitats. The shape of the beak indicates it could have captured reptiles and

Contemporary accounts are repetitive and do not shed much light on the life history of the red rail. Based on fossil localities, the bird widely occurred on Mauritius, in montane, lowland, and coastal habitats. The shape of the beak indicates it could have captured reptiles and  Hume noted that the front of the red rail's jaws were pitted with numerous foramina, running from the nasal aperture to almost the tip of the premaxilla. These were mostly oval, varying in depth and inclination, and became shallower hindward from the tip. Similar foramina can be seen in probing birds, such as kiwis, ibises, and

Hume noted that the front of the red rail's jaws were pitted with numerous foramina, running from the nasal aperture to almost the tip of the premaxilla. These were mostly oval, varying in depth and inclination, and became shallower hindward from the tip. Similar foramina can be seen in probing birds, such as kiwis, ibises, and  While it was swift and could escape when chased, it was easily lured by waving a red cloth, which they approached to attack; a similar behaviour was noted in its relative, the Rodrigues rail. The birds could then be picked up, and their cries when held would draw more individuals to the scene, as the birds, which had evolved in the absence of mammalian

While it was swift and could escape when chased, it was easily lured by waving a red cloth, which they approached to attack; a similar behaviour was noted in its relative, the Rodrigues rail. The birds could then be picked up, and their cries when held would draw more individuals to the scene, as the birds, which had evolved in the absence of mammalian

To the sailors who visited Mauritius from 1598 and onwards, the fauna was mainly interesting from a culinary standpoint. The dodo was sometimes considered rather unpalatable, but the red rail was a popular

To the sailors who visited Mauritius from 1598 and onwards, the fauna was mainly interesting from a culinary standpoint. The dodo was sometimes considered rather unpalatable, but the red rail was a popular  Hoffman's account refers to the red rail by the German version of the Dutch name originally applied to the dodo, "dod-aers", and John Marshall used "red hen" interchangeably with "dodo" in 1668. Milne-Edwards suggested that early travellers may have confused young dodos with red rails. The British ornithologist

Hoffman's account refers to the red rail by the German version of the Dutch name originally applied to the dodo, "dod-aers", and John Marshall used "red hen" interchangeably with "dodo" in 1668. Milne-Edwards suggested that early travellers may have confused young dodos with red rails. The British ornithologist

Many terrestrial rails are flightless, and island populations are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic (human-caused) changes; as a result, rails have suffered more extinctions than any other family of birds. All six endemic species of Mascarene rails are extinct, all caused by human activities. In addition to hunting pressure by humans, the fact that the red rail nested on the ground made it vulnerable to pigs and other introduced animals, which ate their eggs and young, probably contributing to its extinction, according to Cheke. Hume pointed out that the red rail had coexisted with introduced rats since at least the 14th century, which did not appear to have affected them (as they seem to have been relatively common in the 1680s), and they were probably able to defend their nests (''Dryolimnas'' rails have been observed killing rats, for example). They also seemed to have managed to survive alongside humans as well as introduced pigs and

Many terrestrial rails are flightless, and island populations are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic (human-caused) changes; as a result, rails have suffered more extinctions than any other family of birds. All six endemic species of Mascarene rails are extinct, all caused by human activities. In addition to hunting pressure by humans, the fact that the red rail nested on the ground made it vulnerable to pigs and other introduced animals, which ate their eggs and young, probably contributing to its extinction, according to Cheke. Hume pointed out that the red rail had coexisted with introduced rats since at least the 14th century, which did not appear to have affected them (as they seem to have been relatively common in the 1680s), and they were probably able to defend their nests (''Dryolimnas'' rails have been observed killing rats, for example). They also seemed to have managed to survive alongside humans as well as introduced pigs and

flightless

Flightless birds are birds that through evolution lost the ability to fly. There are over 60 extant species, including the well known ratites (ostriches, emu, cassowaries, rheas, and kiwi) and penguins. The smallest flightless bird is the ...

rail

Rail or rails may refer to:

Rail transport

*Rail transport and related matters

*Rail (rail transport) or railway lines, the running surface of a railway

Arts and media Film

* ''Rails'' (film), a 1929 Italian film by Mario Camerini

* ''Rail'' ( ...

. It was endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to the Mascarene

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of the islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of Réunion. Thei ...

island of Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

, east of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

. It had a close relative on Rodrigues island, the likewise extinct Rodrigues rail

The Rodrigues rail (''Erythromachus leguati''), also known as Leguat's gelinote or Leguat's rail, is an extinct species of the rail family that was endemic to the Mascarene island of Rodrigues, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. It is ge ...

(''Erythromachus leguati''), with which it is sometimes considered congeneric

Congener may refer to:

* A thing or person of the same kind as another, or of the same group.

* Congener (biology), organisms within the same genus.

* Congener (chemistry), related chemicals, e.g., elements in the same group of the periodic table. ...

. Its relationship with other rails is unclear. Rails often evolve flightlessness when adapting to isolated islands, free of mammalian predators. The red rail was a little larger than a chicken and had reddish, hairlike plumage, with dark legs and a long, curved beak. The wings were small, and its legs were slender for a bird of its size. It was similar to the Rodrigues rail, but was larger, and had proportionally shorter wings. It has been compared to a kiwi

Kiwi most commonly refers to:

* Kiwi (bird), a flightless bird native to New Zealand

* Kiwi (nickname), a nickname for New Zealanders

* Kiwifruit, an edible berry

* Kiwi dollar or New Zealand dollar, a unit of currency

Kiwi or KIWI may also ref ...

or a limpkin

The limpkin (''Aramus guarauna''), also called carrao, courlan, and crying bird, is a large wading bird related to rails and cranes, and the only extant species in the family Aramidae. It is found mostly in wetlands in warm parts of the America ...

in appearance and behaviour.

It is believed to have fed on invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordat ...

, and snail shells have been found with damage matching an attack by its beak. Human hunters took advantage of an attraction red rails had to red objects by using coloured cloth to lure the birds so that they could be beaten with sticks. Until subfossil remains were discovered in the 1860s, scientists only knew the red rail from 17th century descriptions and illustrations. These were thought to represent several different species, which resulted in a large number of invalid junior synonyms

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linn ...

. It has been suggested that all late 17th-century accounts of the dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest genetic relative was the also-extinct Rodrigues solitaire. The ...

actually referred to the red rail, after the former had become extinct. The last mention of a red rail sighting is from 1693, and it is thought to have gone extinct around 1700, due to predation by humans and introduced species

An introduced species, alien species, exotic species, adventive species, immigrant species, foreign species, non-indigenous species, or non-native species is a species living outside its native distributional range, but which has arrived ther ...

.

Taxonomy

The red rail was first mentioned as "Indian river woodcocks" by the Dutch ships’ pilot Heyndrick Dircksz Jolinck in 1598. By the 19th century, the bird was known only from a few contemporary descriptions referring to red "hens" and names otherwise used forgrouse

Grouse are a group of birds from the order Galliformes, in the family Phasianidae. Grouse are presently assigned to the tribe Tetraonini (formerly the subfamily Tetraoninae and the family Tetraonidae), a classification supported by mitochondria ...

or partridges

A partridge is a medium-sized galliform bird in any of several genera, with a wide native distribution throughout parts of Europe, Asia and Africa. Several species have been introduced to the Americas. They are sometimes grouped in the Perdic ...

in Europe, as well as the sketches of the Dutch merchant Pieter van den Broecke

Pieter van den Broecke (25 February 1585, Antwerp – 1 December 1640, Strait of Malacca) was a Dutch cloth merchant in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and one of the first Dutchmen to taste coffee. He also went to Angola three ...

and the English traveller Sir Thomas Herbert

Sir Thomas Herbert, 1st Baronet (1606–1682), was an English traveller, historian and a gentleman of the bedchamber of King Charles I while Charles was in the custody of Parliament (from 1647 until the king's execution in January 1649).

Biogr ...

from 1646 and 1634. While they differed in some details, they were thought to depict a single species by the English naturalist Hugh Edwin Strickland

Hugh Edwin Strickland (2 March 1811 – 14 September 1853) was an English geologist, ornithologist, naturalist and systematist. Through the British Association, he proposed a series of rules for the nomenclature of organisms in zoology, known as ...

in 1848. The Belgian scientist Edmond de Sélys Longchamps

Baron Michel Edmond de Selys Longchamps (25 May 1813 – 11 December 1900) was a Belgian Liberal Party politician and scientist. Selys Longchamps has been regarded as the founding figure of odonatology, the study of the dragonflies and damselfl ...

coined the scientific name ''Apterornis bonasia'' based on the old accounts mentioned by Strickland. He also included two other Mascarene birds, at the time only known from contemporary accounts, in the genus ''Apterornis'': the Réunion ibis

The Réunion ibis or Réunion sacred ibis (''Threskiornis solitarius'') is an extinct species of ibis that was endemic to the volcanic island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. The first subfossil remains were found in 1974, and the ibis was firs ...

(now ''Threskiornis solitarius''); and the Réunion swamphen (now ''Porphyrio caerulescens''). He thought them related to the dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest genetic relative was the also-extinct Rodrigues solitaire. The ...

and Rodrigues solitaire

The Rodrigues solitaire (''Pezophaps solitaria'') is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Rodrigues, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Genetically within the family of pigeons and doves, it was most closely relate ...

, due to their shared rudimentary wings, tail, and the disposition of their digits.

The name ''Apterornis'' had already been used for a different extinct bird genus from

The name ''Apterornis'' had already been used for a different extinct bird genus from New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

(originally spelled '' Aptornis'', the adzebills) by the British biologist Richard Owen earlier in 1848. The meaning of ''bonasia'' is unclear. Some early accounts refer to red rails by the vernacular names for the hazel grouse

The hazel grouse (''Tetrastes bonasia''), sometimes called the hazel hen, is one of the smaller members of the grouse family of birds. It is a sedentary species, breeding across the Palearctic as far east as Hokkaido, and as far west as eastern a ...

, ''Tetrastes bonasia'', so the name evidently originates there. The name itself perhaps refers to ''bonasus'', meaning "bull" in Latin, or ''bonum'' and ''assum'', meaning "good roast". It has also been suggested to be a Latin form of the French word ''bonasse'', meaning simple-minded or good-natured. It is also possible that the name alludes to bulls due the bird being said to have had a similar attraction to the waving of red cloth.

The German ornithologist Hermann Schlegel

Hermann Schlegel (10 June 1804 – 17 January 1884) was a German ornithologist, herpetologist and ichthyologist.

Early life and education

Schlegel was born at Altenburg, the son of a brassfounder. His father collected butterflies, which stimulate ...

thought van den Broecke's sketch depicted a smaller dodo species from Mauritius, and that the Herbert sketch showed a dodo from Rodrigues, and named them ''Didus broecki'' and ''Didus herberti'' in 1854. In the 1860s, subfossil foot bones and a lower jaw were found along with remains of other Mauritian animals in the Mare aux Songes

The Mare aux Songes () swamp is a lagerstätte located close to the sea in south eastern Mauritius. Many subfossils of recently extinct animals have accumulated in the swamp, which was once a lake, and some of the first subfossil remains of dodos w ...

swamp, and were identified as belonging to a rail by the French zoologist Alphonse Milne-Edwards

Alphonse Milne-Edwards (Paris, 13 October 1835 – Paris, 21 April 1900) was a French mammalogist, ornithologist, and carcinologist. He was English in origin, the son of Henri Milne-Edwards and grandson of Bryan Edwards, a Jamaican planter who se ...

in 1866. In 1968, the Austrian naturalist Georg Ritter von Frauenfeld brought attention to paintings by the Flemish artist Jacob Hoefnagel depicting animals in the royal menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the Hous ...

in Prague, including a dodo and a bird he named ''Aphanapteryx imperialis''. ''Aphanapteryx'' means "invisible-wing", from Greek ''aphanēs'', unseen, and ''pteryx'', wing. He compared it with the birds earlier named form old accountss, and found its beak similar to that of a kiwi

Kiwi most commonly refers to:

* Kiwi (bird), a flightless bird native to New Zealand

* Kiwi (nickname), a nickname for New Zealanders

* Kiwifruit, an edible berry

* Kiwi dollar or New Zealand dollar, a unit of currency

Kiwi or KIWI may also ref ...

or ibis

The ibises () (collective plural ibis; classical plurals ibides and ibes) are a group of long-legged wading birds in the family Threskiornithidae, that inhabit wetlands, forests and plains. "Ibis" derives from the Latin and Ancient Greek word ...

. In 1869, Milne-Edwards proposed that the subfossil bones from Mauritius belonged to the bird in the Hoiefnagel painting, and combined the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

name with the older specific name ''broecki''. Due to nomenclatural priority, the genus name was later combined with the oldest species name ''bonasia''.

In the 1860s, the travel journal of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

ship ''Gelderland'' (1601–1603) was rediscovered, which contains good sketches of several now-extinct Mauritian birds attributed to the artist Joris Laerle, including an unlabelled red rail. More fossils were later found by Theodore Sauzier, who had been commissioned to explore the "historical souvenirs" of Mauritius in 1889. In 1899, an almost complete specimen was found by the barber Louis Etienne Thirioux, who also found important dodo remains, in a cave in the Vallée des Prêtres; this is the most completely known red rail specimen, and is catalogued as MI 923 in the Mauritius Institute. The second most complete individual (specimen CMNZ AV6284) also mainly consists of bones from the Thirioux collection. More material has since been found in various settings. The yellowish colouration mentioned by English traveller Peter Mundy in 1638 instead of the red of other accounts was used by the Japanese ornithologist Masauji Hachisuka

, 18th Marquess Hachisuka, was a Japanese ornithologist and aviculturist.Delacour, J. (1953) The Dodo and Kindred Birds by Masauji Hachisuka (Review). The Condor 55 (4): 223.Peterson, A. P. (2013Author Index: Hachisuka, Masauji (Masa Uji), marqu ...

in 1937 as an argument for this referring to a distinct species, ''Kuina mundyi'', but the American ornithologist Storrs L. Olson suggested in 1977 it was possibly due to the observed bird being a juvenile.

Evolution

Apart from being a close relative of the

Apart from being a close relative of the Rodrigues rail

The Rodrigues rail (''Erythromachus leguati''), also known as Leguat's gelinote or Leguat's rail, is an extinct species of the rail family that was endemic to the Mascarene island of Rodrigues, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. It is ge ...

, the relationships of the red rail are uncertain. The two are commonly kept as separate genera, ''Aphanapteryx'' and ''Erythromachus'', but have also been united as species of ''Aphanapteryx'' at times. They were first generically synonymised by the British ornithologists Edward Newton

Sir Edward Newton (10 November 1832 – 25 April 1897) was a British colonial administrator and ornithologist.

He was born at Elveden Hall, Suffolk the sixth and youngest son of William Newton, MP. He was the brother of ornithologist Alfre ...

and Albert Günther

Albert Karl Ludwig Gotthilf Günther FRS, also Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf Günther (3 October 1830 – 1 February 1914), was a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. Günther is ranked the second-most productive re ...

in 1879, due to skeletal similarities. In 1892, the Scottish naturalist Henry Ogg Forbes

Henry Ogg Forbes LLD (30 January 1851 – 27 October 1932) was a Scottish explorer, ornithologist, and botanist. He also described a new species of spider, '' Thomisus decipiens''.

Biography

Forbes was the son of Rev Alexander Forbes M.A. (182 ...

described Hawkins's rail

Hawkins's rail (''Diaphorapteryx hawkinsi''), also called the giant Chatham Island rail or mehonui, is an extinct species of flightless rail. It was endemic to the Chatham Islands east of New Zealand. It is known to have existed only on the main ...

, an extinct species of rail from the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ) (Moriori: ''Rēkohu'', 'Misty Sun'; mi, Wharekauri) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island. They are administered as part of New Zealand. The archipelago consists of about te ...

located east of New Zealand, as a new species of ''Aphanapteryx''; ''A. hawkinsi''. He found the Chatham Islands species more similar to the red rail than the latter was to the Rodrigues rail, and proposed that the Mascarene Islands had once been connected with the Chatham Islands, as part of a lost continent

Lost lands are islands or continents believed by some to have existed during pre-history, but to have since disappeared as a result of catastrophic geological phenomena.

Legends of lost lands often originated as scholarly or scientific theor ...

he called "Antipodea". Forbes moved the Chatham Islands bird to its own genus, ''Diaphorapteryx'', in 1893, on the recommendation of Newton, but later reverted to his older name. The idea that the Chatham Islands bird was closely related to the red rail and the idea of a connection between the Mascarenes and the Chatham Islands were later criticised by the British palaeontologist Charles William Andrews

Charles William Andrews (30 October 1866 – 25 May 1924) F.R.S., was a British palaeontologist whose career as a vertebrate paleontologist, both as a curator and in the field, was spent in the services of the British Museum, Department of Ge ...

due to no other species being shared between the islands, and the German ornithologist Hans F. Gadow explained the similarity between the two rails as parallel evolution

Parallel evolution is the similar development of a trait in distinct species that are not closely related, but share a similar original trait in response to similar evolutionary pressure.Zhang, J. and Kumar, S. 1997Detection of convergent and paral ...

.

In 1945, the French palaeontologist Jean Piveteau

Jean Piveteau (23 September 1899 – 7 March 1991) was a distinguished French vertebrate paleontologist. He was elected to the French Academy of Sciences in 1956 and served as the institute's president in 1973.

References

External links Membe ...

found skull features of the red and Rodrigues rail different enough for generic separation, and in 1977, Olson stated that though the two species were similar and derived from the same stock, they had also diverged considerably, and should possibly be kept separate. Based on geographic location and the morphology of the nasal bones

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

, Olson suggested that they were related to the genera ''Gallirallus

''Gallirallus'' is a genus of rails that live in the Australasian-Pacific region. The genus is characterised by an ability to colonise relatively small and isolated islands and thereafter to evolve flightless forms, many of which became extinct ...

'', ''Dryolimnas

The genus ''Dryolimnas'' comprises birds in the rail family. The Réunion rail, a member of this genus, became extinct in the 17th century. The white-throated rail of Aldabra is the last surviving flightless bird

Flightless birds are b ...

'', '' Atlantisia'', and ''Rallus

''Rallus'' is a genus of wetland birds of the rail family. Sometimes, the genera ''Lewinia'' and ''Gallirallus'' are included in it. Six of the species are found in the Americas, and the three species found in Eurasia, Africa and Madagascar ar ...

''. The American ornithologist Bradley C. Livezey

Bradley Curtis Livezey (June 15, 1954 – February 8, 2011) was an American ornithologist with scores of publications. His main research included the evolution of flightless birds, the systematics of birds, and the ecology and behaviour of steame ...

was unable to determine the affinities of the red and Rodrigues rail in 1998, stating that some of the features uniting them and some other rails were associated with the loss of flight rather than common descent. He also suggested that the grouping of the red and Rodrigues rail into the same genus may have been influenced by their geographical distribution. The French palaeontologist Cécile Mourer-Chauviré and colleagues also considered the two as belonging to separate genera in 1999.

Rails have reached many oceanic archipelagos

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

, which has frequently led to speciation and evolution of flightlessness. According to the British researchers Anthony S. Cheke and Julian P. Hume

Julian Pender Hume (born 3 March 1960) is an English palaeontologist, artist and writer who lives in Wickham, Hampshire. He was born in Ashford, Kent, and grew up in Portsmouth, England. He attended Crookhorn Comprehensive School between 1971 an ...

in 2008, the fact that the red rail lost much of its feather structure indicates it was isolated for a long time. These rails may be of Asian origin, like many other Mascarene birds. In 2019, Hume supported the distinction of the two genera, and cited the relation between the extinct Mauritius scops owl and the Rodrigues scops owl as another example of the diverging evolutionary paths on these islands. He stated that the relationships of the red and Rodrigues rails was more unclear than that of other extinct Mascarene rails, with many of their distinct features being related to flightlessness and modifications to their jaws due to their diet, suggesting long time isolation. He suggested their ancestors could have arrived on the Mascarenes during the middle Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

at the earliest, but it may have happened more recently. The speed of which these features evolved may also have been affected by gene flow, resource availability, and climate events, and flightlessness can evolve rapidly in rails, as well as repeatedly within the same groups, as seen in for example ''Dryolimnas'', so the distinctness of the red and Rodrigues rails may not have taken long to evolve (some other specialised rails evolved in less than 1–3 million years). Hume suggested that the two rails were probably related to ''Dryolimnas'', but their considerably different morphology made it difficult to establish how. In general, rails are adept at colonising islands, and can become flightless within few generations in suitable environments, for example without predators, yet this also makes them vulnerable to human activities.

Description

sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

, as is common among rails. It was about long, and the male may have weighed and the female . Its plumage was reddish brown all over, and the feathers were fluffy and hairlike; the tail was not visible in the living bird and the short wings likewise also nearly disappeared in the plumage. It had a long, slightly curved, brown bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

, and some illustrations suggest it had a nape

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , "spinal marrow"). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''nu ...

crest. The bird perhaps resembled a lightly built kiwi, and it has also been likened to a limpkin

The limpkin (''Aramus guarauna''), also called carrao, courlan, and crying bird, is a large wading bird related to rails and cranes, and the only extant species in the family Aramidae. It is found mostly in wetlands in warm parts of the America ...

, both in appearance and behaviour.

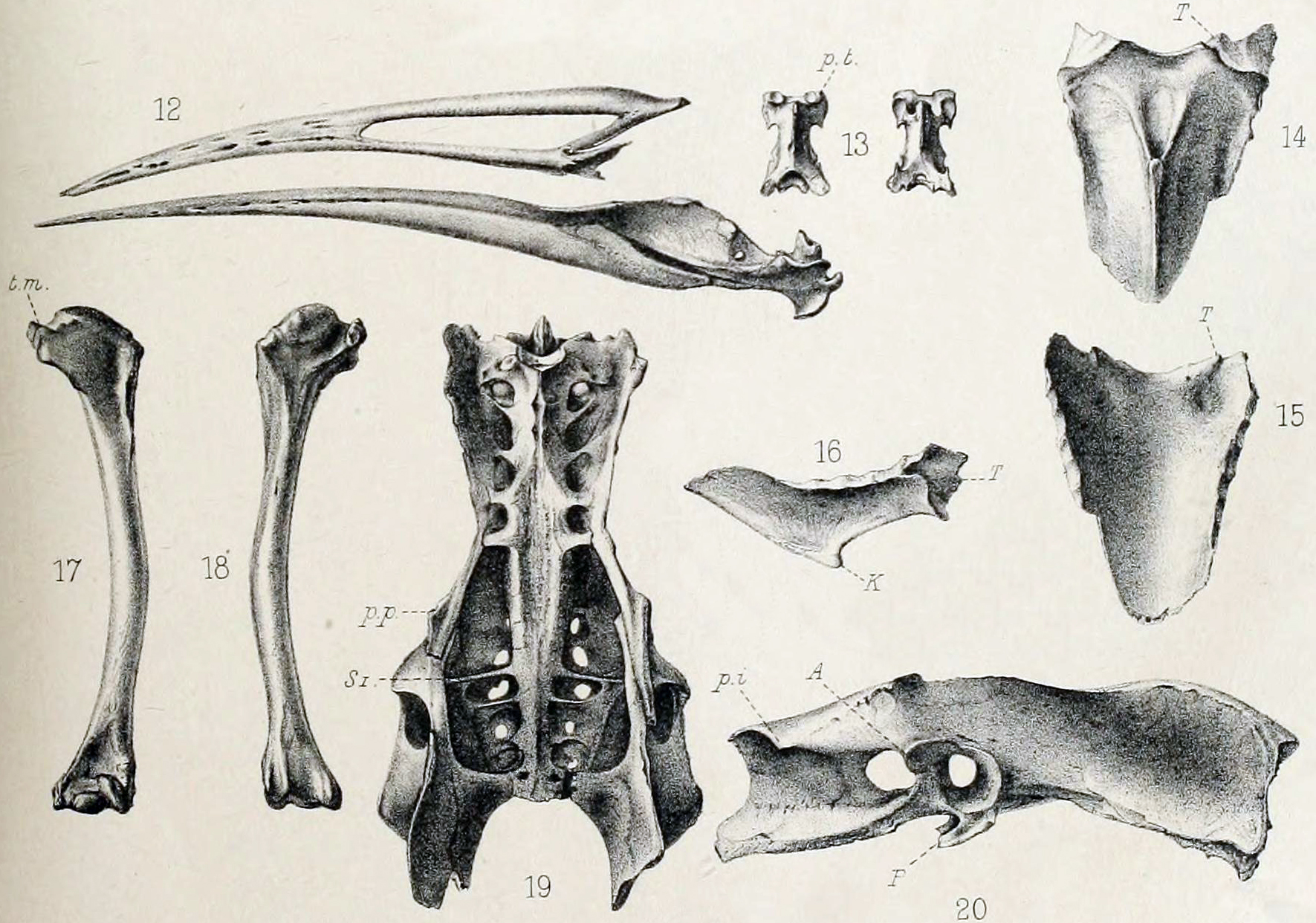

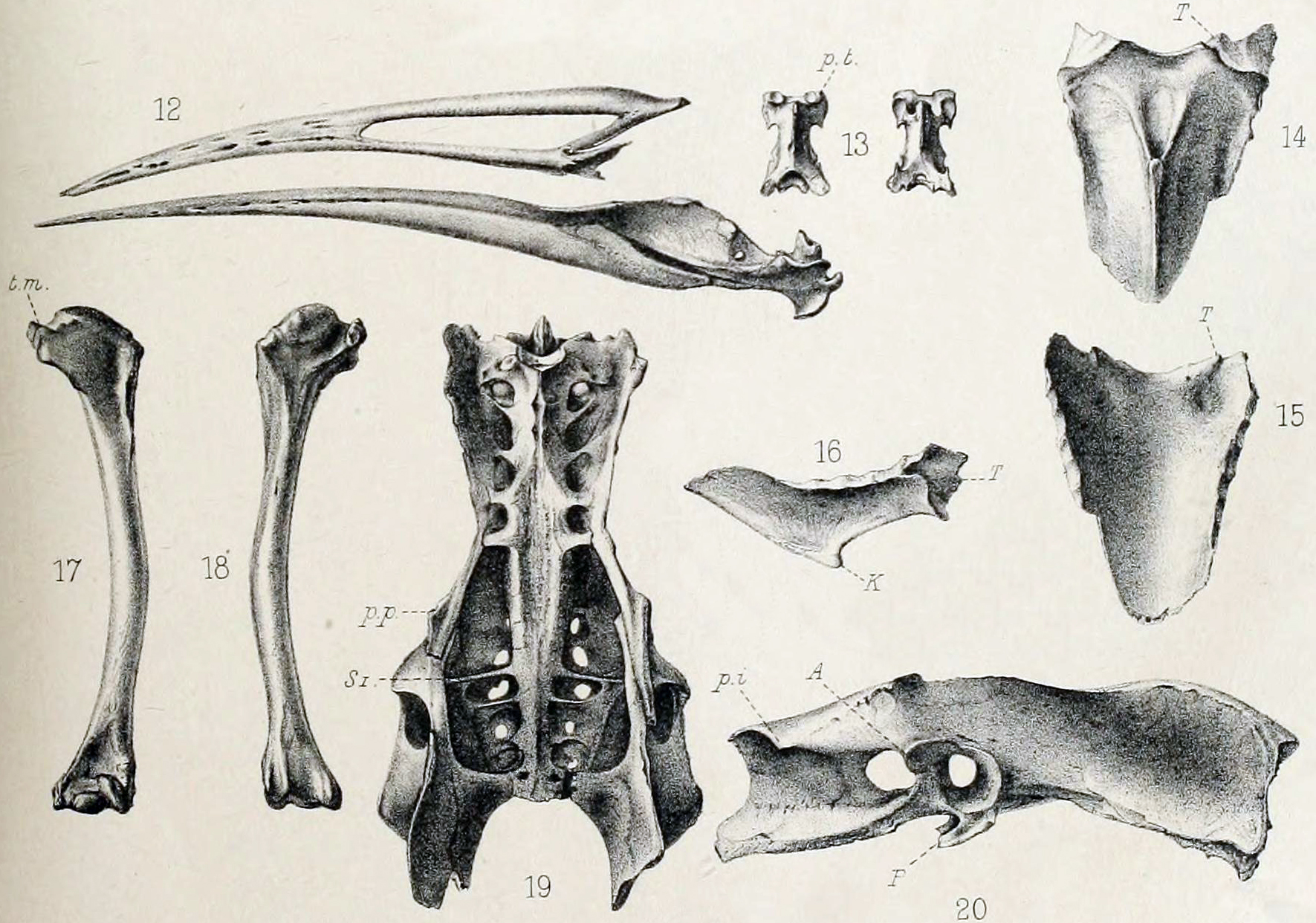

The cranium of the red rail was the largest among Mascarene rails, and was compressed from top to bottom in side view. The premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

that comprised most of the upper bill was long (nearly 47% longer than the cranium) and narrow, and ended in a sharp point. The narial (nostril) openings were 50% of the rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

's length, and prominent, elongate foramina

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (;Entry "foramen"

in

(openings) ran almost to the front edge of the narial opening. The mandibular rostrum of the lower jaw was long, with the length of the mandibular symphysis (where the halves of the mandible connect) being about 79% of the cranium's length. The mandible had large, deep set foramina, which ran almost up to a deep sulcus (furrow). Hume examined all available upper beaks in 2019, and while he found no differences in curvature, he thought the differences in length was most likely due to sexual dimorphism.

The in

scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

(shoulder blade) was wide in side view, and the coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

was comparatively short, with a wide shaft. The sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sha ...

(breast bone) and humerus (upper arm bone) were small, indicating that it had lost the power of flight. The humerus was , and its shaft was strongly curved from top to bottom. The ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

(lower arm bone) was short and strongly arched from top to bottom. Its legs were long and slender for such a large bird, but the pelvis was very wide, robust, and compact, and was in length. The femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

(thigh-bone) was very robust, long, and the upper part of the shaft was strongly arched. The tibiotarsus

The tibiotarsus is the large bone between the femur and the tarsometatarsus in the leg of a bird. It is the fusion of the proximal part of the tarsus with the tibia.

A similar structure also occurred in the Mesozoic Heterodontosauridae. These s ...

(lower leg bone) was large and robust, especially the upper and lower ends, and was long. The fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity i ...

was short and robust. The tarsometatarsus (ankle bone) was large and robust, and long. The red rail differed from the Rodrigues rail in having a proportionately shorter humerus, a narrower and longer skull, and having shorter and higher nostrils. They differed considerably in plumage, based on early descriptions. The red rail was also larger, with somewhat smaller wings, but their leg proportions were similar. The pelvis and sacrum was also similar. The Dutch ornithologist Marc Herremans suggested in 1989 that the red and Rodrigues rails were neotenic

Neoteny (), also called juvenilization,Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT. is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny is found in modern humans compa ...

, with juvenile features such as weak pectoral apparatuses and downy plumage.

Contemporary descriptions

Mundy visited Mauritius in 1638 and described the red rail as follows:

Another English traveller, John Marshall, described the bird as follows in 1668:

Mundy visited Mauritius in 1638 and described the red rail as follows:

Another English traveller, John Marshall, described the bird as follows in 1668:

Contemporary depictions

The two most realistic contemporary depictions of red rails, the Hoefnagel painting from ca. 1610 and the sketches from the ''Gelderland'' ship's journal from 1601 attributed to Laerle, where brought to attention in the 19th century. Much information about the bird's appearance comes from Hoefnagel's painting, based on a bird in the menagerie of

The two most realistic contemporary depictions of red rails, the Hoefnagel painting from ca. 1610 and the sketches from the ''Gelderland'' ship's journal from 1601 attributed to Laerle, where brought to attention in the 19th century. Much information about the bird's appearance comes from Hoefnagel's painting, based on a bird in the menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the Hous ...

around 1610. It is the only unequivocal coloured depiction of the species, showing the plumage as reddish brown, but it is unknown whether it was based on a stuffed or living specimen. The bird had most likely been brought alive to Europe, as it is unlikely that taxidermists were on board the visiting ships, and spirits were not yet used to preserve biological specimens. Most tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

specimens were preserved as dried heads and feet. It had probably lived in the emperor's zoo for a while together with the other animals painted for the same series. The painting was discovered in the emperor's collection and published in 1868 by Georg von Frauenfeld, along with a painting of a dodo from the same collection and artist. This specimen is thought to have been the only red rail that ever reached Europe.

The red rail depicted in the ''Gelderland'' journal appears to have been stunned or killed, and the sketch is the earliest record of the species. It is the only illustration of the species drawn on Mauritius, and according to Hume, the most accurate depiction. The image was sketched with pencil and finished in ink, but details such as a deeper beak and the shoulder of the wing are only seen in the underlying sketch. In addition, there are three rather crude black-and-white sketches, but differences in them were enough for some authors to suggest that each image depicted a distinct species, leading to the creation of several scientific names which are now synonyms. An illustration in van den Broecke's 1646 account (based on his stay on Mauritius in 1617) shows a red rail next to a dodo and a one-horned goat, but is not referenced in the text. An illustration in Herbert's 1634 account (based on his stay in 1629) shows a red rail between a broad-billed parrot and a dodo, and has been referred to as "extremely crude" by Hume. Mundy's 1638 illustration was published in 1919.

As suggested by Greenway, there are also depictions of what appears to be a red rail in three of the Dutch artist

The red rail depicted in the ''Gelderland'' journal appears to have been stunned or killed, and the sketch is the earliest record of the species. It is the only illustration of the species drawn on Mauritius, and according to Hume, the most accurate depiction. The image was sketched with pencil and finished in ink, but details such as a deeper beak and the shoulder of the wing are only seen in the underlying sketch. In addition, there are three rather crude black-and-white sketches, but differences in them were enough for some authors to suggest that each image depicted a distinct species, leading to the creation of several scientific names which are now synonyms. An illustration in van den Broecke's 1646 account (based on his stay on Mauritius in 1617) shows a red rail next to a dodo and a one-horned goat, but is not referenced in the text. An illustration in Herbert's 1634 account (based on his stay in 1629) shows a red rail between a broad-billed parrot and a dodo, and has been referred to as "extremely crude" by Hume. Mundy's 1638 illustration was published in 1919.

As suggested by Greenway, there are also depictions of what appears to be a red rail in three of the Dutch artist Roelant Savery

Roelant Savery (or ''Roeland(t) Maertensz Saverij'', or ''de Savery'', or many variants; 1576 – buried 25 February 1639) was a Flanders-born Dutch Golden Age painter.

Life

Savery was born in Kortrijk. Like so many other artists, he belonge ...

's paintings. In his famous ''Edwards' Dodo'' painting from 1626, a rail-like bird is seen swallowing a frog behind the dodo, but Hume has doubted this identification and that of red rails in other Savery paintings, suggesting may instead show Eurasian bitterns. In 1977, the American ornithologist Sidney Dillon Ripley noted a bird resembling a red rail figured in the Italian artist Jacopo Bassano

Jacopo Bassano (c. 1510 – 14 February 1592), known also as Jacopo dal Ponte, was an Italian painter who was born and died in Bassano del Grappa near Venice, and took the village as his surname. Trained in the workshop of his father, Francesco t ...

's painting ''Arca di Noè'' ("Noah's Ark

Noah's Ark ( he, תיבת נח; Biblical Hebrew: ''Tevat Noaḥ'')The word "ark" in modern English comes from Old English ''aerca'', meaning a chest or box. (See Cresswell 2010, p.22) The Hebrew word for the vessel, ''teva'', occurs twice in ...

") from ca. 1570. Cheke pointed out that it is doubtful that a Mauritian bird could have reached Italy this early, but the attribution may be inaccurate, as Bassano had four artist sons who used the same name. A similar bird is also seen in the Flemish artist Jan Brueghel the Elder

Jan Brueghel (also Bruegel or Breughel) the Elder (, ; ; 1568 – 13 January 1625) was a Flemish painter and draughtsman. He was the son of the eminent Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder. A close friend and frequent collabora ...

's ''Noah's Ark'' painting. Hume concluded that these paintings also show Eurasian bitterns rather than red rails.

Behaviour and ecology

Contemporary accounts are repetitive and do not shed much light on the life history of the red rail. Based on fossil localities, the bird widely occurred on Mauritius, in montane, lowland, and coastal habitats. The shape of the beak indicates it could have captured reptiles and

Contemporary accounts are repetitive and do not shed much light on the life history of the red rail. Based on fossil localities, the bird widely occurred on Mauritius, in montane, lowland, and coastal habitats. The shape of the beak indicates it could have captured reptiles and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s, and the differences in bill length suggests the sexes foraged on items of different sizes. It may also have scavenged breeding colonies of birds and nesting-sites of tortoises

Tortoises () are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin: ''tortoise''). Like other turtles, tortoises have a turtle shell, shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, ...

, as the Rodrigues rail did. No contemporary accounts were known to mention the red rail's diet, until the 1660s report of Johannes Pretorius about his stay on Mauritius was published in 2015, where he mentioned that the bird "scratches in the earth with its sharp claws like a fowl to find food such as worms under the fallen leaves."

Milne-Edwards suggested that since the tip of the red rail's bill was sharp and strong, it fed by crushing molluscs

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is estim ...

and other shells, like oystercatchers

The oystercatchers are a group of waders forming the family Haematopodidae, which has a single genus, ''Haematopus''. They are found on coasts worldwide apart from the polar regions and some tropical regions of Africa and South East Asia. The e ...

do. There were many endemic land-snails on Mauritius, including the large, extinct ''Tropidophora carinata

''Tropidophora carinata'' is a species of land snail with a gill and an operculum, a terrestrial gastropod mollusk in the family Pomatiidae.

This species was found in Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Ma ...

'', and subfossil shells have been found with puncture holes on their lower surfaces, which suggest predation by birds, probably matching attacks from the beak of the red rail. The similarly sized weka

The weka, also known as the Māori hen or woodhen (''Gallirallus australis'') is a flightless bird species of the rail family. It is endemic to New Zealand. It is the only extant member of the genus '' Gallirallus''. Four subspecies are recogni ...

of New Zealand punctures shells of land-snails to extract meat, but can also swallow ''Powelliphanta

''Powelliphanta'' is a genus of large, air-breathing land snails, pulmonate gastropods in the family Rhytididae, found only in New Zealand. They are carnivorous, eating invertebrates, mostly native earthworms. Often restricted to very small areas ...

'' snails; Hume suggested the red rail was also able to swallow snails whole. Since Pretorius mentioned the red rail searched for worms in leaf-litter, Hume suggested this could refer to nemertean

Nemertea is a phylum of animals also known as ribbon worms or proboscis worms, consisting of 1300 known species. Most ribbon worms are very slim, usually only a few millimeters wide, although a few have relatively short but wide bodies. Many ...

and planarian

A planarian is one of the many flatworms of the traditional class Turbellaria. It usually describes free-living flatworms of the order Tricladida (triclads), although this common name is also used for a wide number of free-living platyhelmint ...

worms; Mauritius has endemic species of these groups which live in leaf-litter and rotten wood. He could also have referred to the now extinct worm-snake '' Madatyphlops cariei'', which was up to long, and probably lived in leaf-litter like its relatives do.

Hume noted that the front of the red rail's jaws were pitted with numerous foramina, running from the nasal aperture to almost the tip of the premaxilla. These were mostly oval, varying in depth and inclination, and became shallower hindward from the tip. Similar foramina can be seen in probing birds, such as kiwis, ibises, and

Hume noted that the front of the red rail's jaws were pitted with numerous foramina, running from the nasal aperture to almost the tip of the premaxilla. These were mostly oval, varying in depth and inclination, and became shallower hindward from the tip. Similar foramina can be seen in probing birds, such as kiwis, ibises, and sandpipers

Sandpipers are a large family, Scolopacidae, of waders. They include many species called sandpipers, as well as those called by names such as curlew and snipe. The majority of these species eat small invertebrates picked out of the mud or soil. ...

. While unrelated, these three bird groups share a foraging strategy; they probe for live food beneath substrate, and have elongated bills with clusters of mechanoreceptors concentrated at the tip. Their bill-tips allow them to detect buried prey by sensing cues from the substrate. The foramina on the bill of the red rail were comparable to those in other probing rails with long bills (such as the extinct snipe-rail), though not as concentrated on the tip, and the front end of the bill's curvature also began at the front of the nasal opening (as well as the same point in the mandible). The bill's tip was thereby both strong and very sensitive, and a useful tool for probing for invertebrates.

A 1631 letter probably by the Dutch lawyer Leonardus Wallesius (long thought lost, but rediscovered in 2017) uses word-play to refer to the animals described, with red rails supposedly being an allegory for soldiers:

While it was swift and could escape when chased, it was easily lured by waving a red cloth, which they approached to attack; a similar behaviour was noted in its relative, the Rodrigues rail. The birds could then be picked up, and their cries when held would draw more individuals to the scene, as the birds, which had evolved in the absence of mammalian

While it was swift and could escape when chased, it was easily lured by waving a red cloth, which they approached to attack; a similar behaviour was noted in its relative, the Rodrigues rail. The birds could then be picked up, and their cries when held would draw more individuals to the scene, as the birds, which had evolved in the absence of mammalian predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

s, were curious and not afraid of humans. Herbert described its behaviour towards red cloth in 1634:

Many other endemic species of Mauritius became extinct after the arrival of humans to the island heavily damaged the ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

, making it hard to reconstruct. Before humans arrived, Mauritius was entirely covered in forests, but very little remains today due to deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated ...

. The surviving endemic fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as ''Biota (ecology ...

is still seriously threatened. The red rail lived alongside other recently extinct Mauritian birds such as the dodo, the broad-billed parrot, the Mascarene grey parakeet, the Mauritius blue pigeon, the Mauritius scops owl, the Mascarene coot, the Mauritian shelduck, the Mauritian duck, and the Mauritius night heron. Extinct Mauritian reptiles include the saddle-backed Mauritius giant tortoise, the domed Mauritius giant tortoise, the Mauritian giant skink, and the Round Island burrowing boa. The small Mauritian flying fox and the snail ''Tropidophora carinata'' lived on Mauritius and Réunion, but became extinct in both islands. Some plants, such as '' Casearia tinifolia'' and the palm orchid, have also become extinct.

Relationship with humans

To the sailors who visited Mauritius from 1598 and onwards, the fauna was mainly interesting from a culinary standpoint. The dodo was sometimes considered rather unpalatable, but the red rail was a popular

To the sailors who visited Mauritius from 1598 and onwards, the fauna was mainly interesting from a culinary standpoint. The dodo was sometimes considered rather unpalatable, but the red rail was a popular gamebird

Galliformes is an order of heavy-bodied ground-feeding birds that includes turkeys, chickens, quail, and other landfowl. Gallinaceous birds, as they are called, are important in their ecosystems as seed dispersers and predators, and are often ...

for the Dutch and French settlers. The reports dwell upon the varying ease with which the bird could be caught according to the hunting method and the fact that when roasted it was considered similar to pork

Pork is the culinary name for the meat of the domestic pig (''Sus domesticus''). It is the most commonly consumed meat worldwide, with evidence of pig husbandry dating back to 5000 BCE.

Pork is eaten both freshly cooked and preserved; ...

. The last detailed account of the red rail was by the German pastor Johann Christian Hoffmann, on Mauritius in the early 1670s, who described a hunt as follows:

Alfred Newton

Alfred Newton FRS HFRSE (11 June 18297 June 1907) was an English zoologist and ornithologist. Newton was Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Cambridge University from 1866 to 1907. Among his numerous publications were a four-volume ''Dictionar ...

(brother of Edward) suggested in 1868 that the name of the dodo was transferred to the red rail after the former had gone extinct. Cheke suggested in 2008 that all post 1662 references to "dodos" therefore refer to the rail instead. A 1681 account of a "dodo", previously thought to have been the last, mentioned that the meat was "hard", similar to the description of red hen meat. The British writer Errol Fuller has also cast the 1662 "dodo" sighting in doubt, as the reaction to distress cries of the birds mentioned matches what was described for the red rail.

In 2020, Cheke and the British researcher Jolyon C. Parish suggested that all mentions of dodos after the mid-17th century instead referred to red rails, and that the dodo had disappeared due to predation by feral pigs

The feral pig is a domestic pig which has gone feral, meaning it lives in the wild. They are found mostly in the Americas and Australia. Razorback and wild hog are Americanisms applied to feral pigs or boar-pig hybrids.

Definition

A feral p ...

during a hiatus in settlement of Mauritius (1658–1664). The dodo's extinction therefore was not realised at the time, since new settlers had not seen real dodos, but as they expected to see flightless birds, they referred to the red rail by that name instead. Since red rails probably had larger clutches than dodos (as in other rails) and their eggs could be incubated faster, and their nests were perhaps concealed like those of the Rodrigues rail, they probably bred more efficiently, and were less vulnerable to pigs. They may also have foraged from the digging, scraping and rooting of the pigs, as does the weka.

230 years before Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variatio ...

, the appearance of the red rail and the dodo led Mundy to speculate:

Extinction

Many terrestrial rails are flightless, and island populations are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic (human-caused) changes; as a result, rails have suffered more extinctions than any other family of birds. All six endemic species of Mascarene rails are extinct, all caused by human activities. In addition to hunting pressure by humans, the fact that the red rail nested on the ground made it vulnerable to pigs and other introduced animals, which ate their eggs and young, probably contributing to its extinction, according to Cheke. Hume pointed out that the red rail had coexisted with introduced rats since at least the 14th century, which did not appear to have affected them (as they seem to have been relatively common in the 1680s), and they were probably able to defend their nests (''Dryolimnas'' rails have been observed killing rats, for example). They also seemed to have managed to survive alongside humans as well as introduced pigs and

Many terrestrial rails are flightless, and island populations are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic (human-caused) changes; as a result, rails have suffered more extinctions than any other family of birds. All six endemic species of Mascarene rails are extinct, all caused by human activities. In addition to hunting pressure by humans, the fact that the red rail nested on the ground made it vulnerable to pigs and other introduced animals, which ate their eggs and young, probably contributing to its extinction, according to Cheke. Hume pointed out that the red rail had coexisted with introduced rats since at least the 14th century, which did not appear to have affected them (as they seem to have been relatively common in the 1680s), and they were probably able to defend their nests (''Dryolimnas'' rails have been observed killing rats, for example). They also seemed to have managed to survive alongside humans as well as introduced pigs and crab-eating macaques

The crab-eating macaque (''Macaca fascicularis''), also known as the long-tailed macaque and referred to as the cynomolgus monkey in laboratories, is a cercopithecinae, cercopithecine primate native to Southeast Asia. A species of macaque, the cr ...

.

Since the red rail was referred to by the names of the dodo in the late 1600s, it is uncertain which is the latest account of the latter. When the French traveller François Leguat

François Leguat (1637/1639 – September 1735) was a French explorer and naturalist. He was one of a small group of male French Protestant refugees who in 1691 settled on the then uninhabited island of Rodrigues in the western Indian Ocean. T ...

, who had become familiar with the Rodrigues rail in the preceding years, arrived on Mauritius in 1693, he remarked that the red rail had become rare. He was the last source to mention the bird, so it is assumed that it became extinct around 1700. Feral cats, which are effective predators of ground-inhabiting birds, were established on Mauritius around the late 1680s (to control rats), and this has been cause for rapid disappearance of rails elsewhere, for example on Aldabra Atoll

Aldabra is the world's second-largest coral atoll, lying south-east of the continent of Africa. It is part of the Aldabra Group of islands in the Indian Ocean that are part of the Outer Islands (Seychelles), Outer Islands of the Seychelles, with ...

. Being inquisitive and fearless, Hume suggested the red rail would have been easy prey for cats, and was thereby driven to extinction.

See also

* Holocene extinction *List of extinct birds

Around 129 species of birds have become extinct since 1500, and the rate of extinction seems to be increasing. The situation is exemplified by Hawaii, where 30% of all known recently extinct bird taxa originally lived. Other areas, such as Gua ...

References

External links

* * {{Taxonbar, from=Q844868 Birds described in 1848 Bird extinctions since 1500 Extinct animals of Mauritius Extinct birds of Indian Ocean islands Extinct flightless birds Rallidae