Rafael Leónidas Trujillo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

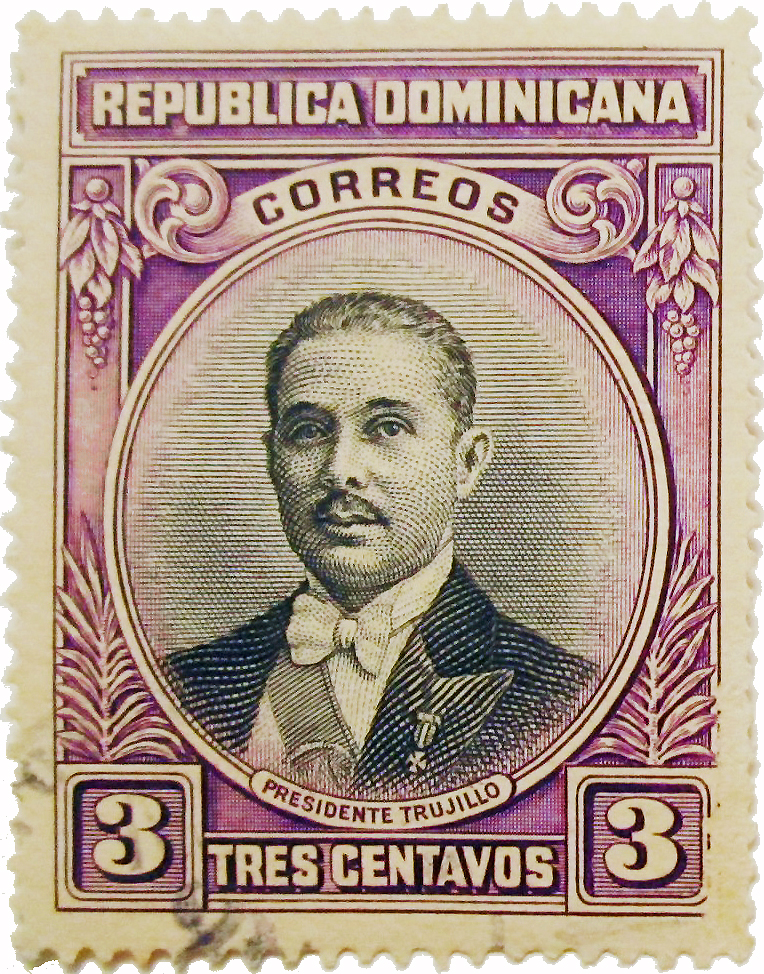

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina ( , ; 24 October 189130 May 1961), nicknamed ''El Jefe'' (, "The Chief" or "The Boss"), was a Dominican dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from February 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He served as president from 1930 to 1938 and again from 1942 to 1952, ruling for the rest of the time as an unelected military strongman under presidents.

Three and a half weeks after Trujillo ascended to the presidency, the destructive Hurricane San Zenon hit Santo Domingo and left 2,000 dead. As a response to the disaster, Trujillo placed the Dominican Republic under martial law and began to rebuild the city. He renamed the rebuilt capital of the Dominican Republic Ciudad Trujillo ("Trujillo City") in his honor and had streets, monuments, and landmarks to honor him throughout the country.

On 16 August 1931, the first anniversary of his inauguration, Trujillo made the

Three and a half weeks after Trujillo ascended to the presidency, the destructive Hurricane San Zenon hit Santo Domingo and left 2,000 dead. As a response to the disaster, Trujillo placed the Dominican Republic under martial law and began to rebuild the city. He renamed the rebuilt capital of the Dominican Republic Ciudad Trujillo ("Trujillo City") in his honor and had streets, monuments, and landmarks to honor him throughout the country.

On 16 August 1931, the first anniversary of his inauguration, Trujillo made the

In 1936, at the suggestion of Mario Fermín Cabral, the Congress of the Dominican Republic voted overwhelmingly to change the name of the capital from

In 1936, at the suggestion of Mario Fermín Cabral, the Congress of the Dominican Republic voted overwhelmingly to change the name of the capital from  Trujillo was eligible to run again in 1938, but, citing the United States example of two presidential terms, he stated, "I voluntarily, and against the wishes of my people, refuse re-election to the high office." In fact, a vigorous re-election campaign had been launched in the middle of 1937 but the international uproar that followed the Haitian massacre later that year forced Trujillo to announce his "return to private life." Consequently, the Dominican Party nominated Trujillo's handpicked successor, 61-year-old vice-president Jacinto Peynado, with Manuel de Jesús Troncoso his running mate. They appeared alone on the ballot in the 1938 election. Trujillo kept his positions as generalissimo of the army and leader of the Dominican Party. It was understood that Peynado was merely a puppet, and Trujillo still held all governing power in the nation. Peynado increased the size of the electric "Dios y Trujillo" sign and died on 7 March 1940, with Troncoso serving out the rest of the term. However, in 1942, with US President Franklin Roosevelt having run for a third term in the United States, Trujillo ran for president again and was elected unopposed. He served for two terms, which he lengthened to five years each. In 1952, under pressure from the Organization of American States, he ceded the presidency to his brother,

Trujillo was eligible to run again in 1938, but, citing the United States example of two presidential terms, he stated, "I voluntarily, and against the wishes of my people, refuse re-election to the high office." In fact, a vigorous re-election campaign had been launched in the middle of 1937 but the international uproar that followed the Haitian massacre later that year forced Trujillo to announce his "return to private life." Consequently, the Dominican Party nominated Trujillo's handpicked successor, 61-year-old vice-president Jacinto Peynado, with Manuel de Jesús Troncoso his running mate. They appeared alone on the ballot in the 1938 election. Trujillo kept his positions as generalissimo of the army and leader of the Dominican Party. It was understood that Peynado was merely a puppet, and Trujillo still held all governing power in the nation. Peynado increased the size of the electric "Dios y Trujillo" sign and died on 7 March 1940, with Troncoso serving out the rest of the term. However, in 1942, with US President Franklin Roosevelt having run for a third term in the United States, Trujillo ran for president again and was elected unopposed. He served for two terms, which he lengthened to five years each. In 1952, under pressure from the Organization of American States, he ceded the presidency to his brother,

Trujillo tended toward peaceful coexistence with the

Trujillo tended toward peaceful coexistence with the

Haiti had historically

Haiti had historically

By the late 1950s, opposition to Trujillo's regime was starting to build to a fever pitch, especially among a younger generation who had no memory of the poverty and instability that had preceded the dictatorship. Many clamored for democratization. The Trujillo regime responded with greater repression. The Military Intelligence Service (SIM) secret police, led by Johnny Abbes, remained as ubiquitous as before. Other nations ostracized the Dominican Republic, compounding the dictator's paranoia.

Trujillo began to interfere more and more in the domestic affairs of neighboring countries. He expressed great contempt for Venezuela's president

By the late 1950s, opposition to Trujillo's regime was starting to build to a fever pitch, especially among a younger generation who had no memory of the poverty and instability that had preceded the dictatorship. Many clamored for democratization. The Trujillo regime responded with greater repression. The Military Intelligence Service (SIM) secret police, led by Johnny Abbes, remained as ubiquitous as before. Other nations ostracized the Dominican Republic, compounding the dictator's paranoia.

Trujillo began to interfere more and more in the domestic affairs of neighboring countries. He expressed great contempt for Venezuela's president

Trujillo and his family amassed enormous wealth. He acquired cattle lands on a grand scale, and went into meat and milk production, operations that soon evolved into

Trujillo and his family amassed enormous wealth. He acquired cattle lands on a grand scale, and went into meat and milk production, operations that soon evolved into

On Tuesday, 30 May 1961, Trujillo was shot and killed when his blue 1957

On Tuesday, 30 May 1961, Trujillo was shot and killed when his blue 1957

Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem

/ref>

''Spooks: The Haunting of America & the Private Use of Secret Agents''

(

"GENERALISIMO E.N., RAFAEL LEONIDAS TRUJILLO MOLINA."

Secretario de Estado de las Fuerzas Armadas. * Timoneda, Joan C. "Institutions as Signals: How Dictators Consolidate Power in Times of Crisis." ''Comparative Politics'', vol. 53, no. 1 (2020), pp. 49–68. * Turits, Richard Lee. ''Foundations of Despotism: Peasants, the Trujillo Regime, and Modernity in Dominican History''. Stanford University Press (2004). .

Biography

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Trujillo Molina, Rafael 1891 births 1961 deaths 1961 murders in North America Anti-Masonry Assassinated Dominican Republic politicians Assassinated heads of state Assassinated people Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Burials at Mingorrubio Cemetery Deaths by firearm in the Dominican Republic Dominican Party politicians Dominican Republic anti-communists Dominican Republic military personnel Dominican Republic people of Canarian descent Dominican Republic people of French descent Dominican Republic people of Haitian descent Dominican Republic people of Spanish descent Dominican Republic Roman Catholics Generalissimos Genocide perpetrators Grand Crosses Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany People from San Cristóbal, Dominican Republic People killed in Central Intelligence Agency operations People of the Cold War Politicide perpetrators Presidents of the Dominican Republic Recipients of the Legion of Honour World War II political leaders Far-right politics in South America

Rafael Estrella

Rafael may refer to:

* Rafael (given name) or Raphael, a name of Hebrew origin

* Rafael, California

* Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, Israeli manufacturer of weapons and military technology

* Hurricane Rafael, a 2012 hurricane

Fiction

* ''R ...

from 3 March 1930 to 16 August 1930; Jacinto Peynado from 16 August 1938 to 7 March 1940; Manuel Troncoso from 7 March 1940 to 18 May 1942; Héctor Trujillo from 16 August 1952 to 3 August 1960; Joaquín Balaguer

Joaquín Antonio Balaguer Ricardo (1 September 1906 – 14 July 2002) was a Dominican politician, scholar, writer, and lawyer. He was President of the Dominican Republic serving three non-consecutive terms for that office from 1960 to 196 ...

from 3 August 1960 until 16 January 1962, 8 months after Trujillo's death His rule of 31 years, known to Dominicans as the Trujillo Era ( es, El Trujillato, links=no or ''La Era de Trujillo''), is considered one of the bloodiest and most corrupt regimes in the Western hemisphere, and centered around a personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

of the ruling family. Trujillo's security forces, including the infamous SIM, were responsible for perhaps as many as 50,000 murders, including between 12,000 and 30,000 Haitians in the infamous Parsley massacre

The Parsley massacre (Spanish: ''el corte'' "the cutting"; Creole: ''kout kouto-a'' "the stabbing") (french: Massacre du Persil; es, Masacre del Perejil; ht, Masak nan Pèsil) was a mass killing of Haitians living in the Dominican Republic's nor ...

in 1937, which continues to affect Dominican-Haitian relations to this day.

During his long rule, the Trujillo government's extensive use of state terrorism

State terrorism refers to acts of terrorism which a state conducts against another state or against its own citizens.Martin, 2006: p. 111.

Definition

There is neither an academic nor an international legal consensus regarding the proper def ...

was prolific even beyond national borders, including the attempted assassination of Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt

Rómulo Ernesto Betancourt Bello (22 February 1908 – 28 September 1981; ), known as "The Father of Venezuelan Democracy", was the president of Venezuela, serving from 1945 to 1948 and again from 1959 to 1964, as well as leader of Acción De ...

in 1960, the abduction and disappearance in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

of the Basque-Dominican exile Jesús Galíndez in 1956, and the murder of Spanish writer José Almoina in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, also in 1960. These acts, particularly the presumed murder of Galindez, a naturalized US citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

, and the murder of the Mirabal sisters

The Mirabal sisters ( es, hermanas Mirabal ) were four sisters from the Dominican Republic, three of whom (Patria, Minerva and María Teresa) opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo () and were involved in clandestine activities against his ...

in 1960, eroded relations between the Dominican Republic and the international community and ushered in OAS

OAS or Oas may refer to:

Chemistry

* O-Acetylserine, amino-acid involved in cysteine synthesis

Computers

* Open-Architecture-System, the main user interface of Wersi musical keyboards

* OpenAPI Specification (originally Swagger Specification) ...

sanctions and economic and military assistance to Dominican opposition forces. After this momentous year large segments of the Dominican establishment, including the military, turned against him.

By 1960, Trujillo had amassed a net worth of $800 million ($8.02 billion today). On 30 May 1961, he was assassinated by conspirators sponsored by the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA). In the immediate aftermath, Trujillo's son Ramfis

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Martínez (5 June 1929 – 27 December 1969), better known as Ramfis Trujillo Martínez, was the adopted son of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic, after whose 1961 assassination he briefly ...

took temporary control of the country, exterminating most of the conspirators. By November 1961, the Trujillo family was pressured into exile by the titular president Balaguer, whole introduced reforms to open up the regime. The murder ushered in civil strife which concluded with the Dominican Civil War

The Dominican Civil War (), also known as the April Revolution (), took place between April 24, 1965, and September 3, 1965, in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. It started when civilian and military supporters of the overthrown democraticall ...

and a US intervention, eventually stabilised under a multi-party system in 1966.

The Trujillo era unfolded in a Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties forme ...

Caribbean environment particularly susceptible to dictators. In the countries of the Caribbean Basin

In Geography, the Caribbean Basin is generally defined as the area running from Florida westward along the Gulf coast, then south along the Mexican coast through Central America and then eastward across the northern coast of South America. This ...

alone, his dictatorship overlapped with those in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, and Haiti. In perspective, the Trujillo dictatorship has been judged more prominent and more brutal than its contemporaries. Trujillo remains a polarizing figure in the Dominican Republic, as the longevity and profound importance of his rule makes a detached evaluation difficult. While his supporters credit him for bringing long-term stability, economic growth and prosperity, doubling life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

of average Dominicans and multiplying the GDP, critics denounce the heavy-handed and violent rule of his 30 years in power, including the murder of tens of thousands, his extreme anti-Haitian sentiment, as well as the Trujillo family's nepotism and looting of the country's natural resources.

Early life

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo y Molina was born on 24 October 1891 inSan Cristóbal, Dominican Republic

San Cristóbal is a city in the southern region of Dominican Republic. It is the municipal (''municipio'') capital of the San Cristóbal province. The municipality is located in a valley at the foothills of the mountains belonging to the Cordille ...

, into a lower-middle-class

In developed nations around the world, the lower middle class is a subdivision of the greater middle class. Universally, the term refers to the group of middle class households or individuals who have not attained the status of the upper middle ...

family.Rafael Trujillo. nternet 2015. The History Channel website. Available from: http://www.history.com/topics/rafael-trujillo ccessed 14 May 2015 His father was José Trujillo Valdez, the son of Silveria Valdez Méndez of colonial Dominican origin and José Trujillo Monagas, a Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

sergeant who arrived in Santo Domingo as a member of the Spanish reinforcement troops during the annexation era. Trujillo's mother was Altagracia Julia Molina Chevalier, later known as Mama Julia, the daughter of Pedro Molina Peña, also of colonial Dominican origin, and the teacher Luisa Erciná Chevalier, whose parents were part of the remaining French descendants in Haiti: Trujillo's maternal great-grandfather, Justin Víctor Turenne Carrié Blaise, was of French descent, while his maternal great-grandmother, Eleonore Juliette Chevallier Moreau, was part of Haiti's mulatto class. Trujillo was the third of eleven children;

His siblings were Virgilio Trujillo (24 July 1887 – 29 July 1967), Flérida Marina Trujillo (10 August 1888 – 13 February 1976), Rosa María Julieta Trujillo (5 April 1893 – 23 October 1980), José Arismendy "Petán" Trujillo (4 October 1895 – 6 May 1969), Amable Romero "Pipi" Trujillo (14 August 1896 – 19 September 1970), Luisa Nieves Trujillo (4 August 1899 – 25 January 1977), Julio Aníbal "Bonsito" Trujillo (16 October 1900 – 2 December 1948), Pedro Vetilio "Pedrito" Trujillo (27 January 1902 – 14 March 1981), Ofelia Japonesa Trujillo (26 May 1905 – 4 February 1978) and Héctor Bienvenido "Negro" Trujillo (6 April 1908 – 19 October 2002). he also had an adopted brother, Luis Rafael "Nene" Trujillo (1935–2005), who was raised in the home of Trujillo Molina.

In 1897, at the age of six, Trujillo was registered in the school of Juan Hilario Meriño. One year later, he transferred to the school of Broughton, where he became a pupil of Eugenio María de Hostos

Eugenio María de Hostos (January 11, 1839 – August 11, 1903), known as "''El Gran Ciudadano de las Américas''" ("The Great Citizen of the Americas"), was a Puerto Rican educator, philosopher, intellectual, lawyer, sociologist, novelist, an ...

and remained there for the rest of his primary schooling. As a child, he was obsessed with his appearance and would place bottle caps on his clothes that mimicked military decorations. At the age of 16, Trujillo got a job as a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

operator, which he held for about three years. Shortly after Trujillo turned to crime: cattle stealing, check counterfeiting, and postal robbery. He spent several months in prison, which did not deter him, as he later formed a violent gang of robbers called ''the 42''.

Rise to power

In 1916, the United States began its occupation of the Dominican Republic following 28 revolutions in 50 years. At the time, Trujillo was twenty-five and worked as a ''guardacampestre'', controlling sugar cane workers at a plantation inBoca Chica

Boca Chica is a municipality ('' municipio'') of the Santo Domingo province in the Dominican Republic. Within the municipality there is one municipal district (''distritos municipal''): La Caleta. As of the 2012 census it had 123,510 inhabita ...

. The occupying force soon established a Dominican army constabulary to impose order. Trujillo joined the National Guard in 1918 with the help of his employer along with US Major James J. MacLean, who was his maternal uncle Teódulo Pina Chevalier's friend, immediately receiving the rank of second lieutenant and training with the US Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

. Allegations of forgery were ignored when Trujillo applied and he was later acquitted by a panel of Marines following plausible accusations of rape and extortion. Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

Richard Malcolm Cutts trained Trujillo further and many Marine leaders praised his abilities at the time, approving his rise among the ranks.

President Horacio Vásquez

Felipe Horacio Vásquez Lajara (October 22, 1860 – March 25, 1936) was a Dominican general and political figure. He served as the president of the Provisional Government Junta of the Dominican Republic in 1899, and again between 1902 and 1903. ...

named Trujillo the commander of the Dominican National Police in 1925, he was named brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in 1927 and in 1928, Trujillo reconstituted the police into the army and created it as an independent armed body under his control. A rebellion or ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' against President Vásquez broke out in February 1930 in Santiago. Trujillo secretly cut a deal with the rebel leader Rafael Estrella Ureña. In return for Trujillo letting Estrella take power, Estrella would allow Trujillo to run for president in new elections. As the rebels marched toward Santo Domingo, Vásquez ordered Trujillo to suppress them. However, feigning "neutrality", Trujillo kept his men in barracks, allowing Estrella's rebels to take the capital virtually unopposed. On 3 March, Estrella was proclaimed acting president, with Trujillo confirmed as head of the police and of the army. As per their agreement, Trujillo became the presidential nominee of the Patriotic Coalition of Citizens (Spanish: ''Coalición patriotica de los ciudadanos''), with Estrella as his running mate. The other candidates became targets of harassment by the army. When it became apparent that the army would allow only Trujillo to campaign unhindered, the other candidates pulled out. Ultimately, the Trujillo-Estrella ticket was proclaimed victorious with an implausible 99 percent of the vote. In a note to the State Department, American ambassador Charles Boyd Curtis wrote that Trujillo received far more votes than actual voters.

In government

Three and a half weeks after Trujillo ascended to the presidency, the destructive Hurricane San Zenon hit Santo Domingo and left 2,000 dead. As a response to the disaster, Trujillo placed the Dominican Republic under martial law and began to rebuild the city. He renamed the rebuilt capital of the Dominican Republic Ciudad Trujillo ("Trujillo City") in his honor and had streets, monuments, and landmarks to honor him throughout the country.

On 16 August 1931, the first anniversary of his inauguration, Trujillo made the

Three and a half weeks after Trujillo ascended to the presidency, the destructive Hurricane San Zenon hit Santo Domingo and left 2,000 dead. As a response to the disaster, Trujillo placed the Dominican Republic under martial law and began to rebuild the city. He renamed the rebuilt capital of the Dominican Republic Ciudad Trujillo ("Trujillo City") in his honor and had streets, monuments, and landmarks to honor him throughout the country.

On 16 August 1931, the first anniversary of his inauguration, Trujillo made the Dominican Party

)

, think_tank =

, student_wing =

, youth_wing =

, womens_wing =

, wing1_title =

, wing1 =

, wing2_title =

, wing2 =

, wing3_title =

, wing3 =

, wing4_title =

, wing4 =

, membership_year =

, membership =

, ideology = T ...

the nation's sole legal political party. However, the country had effectively become a one-party state with Trujillo's inauguration. Government employees were required by law to "donate" 10 percent of their salaries to the national treasury, and there was strong pressure on adult citizens to join the party. Members had to carry a membership card, nicknamed the "palmita" since the cover had a palm tree on it, and a person could be arrested for vagrancy without one. Those who did not join or contribute to the party did so at their own risk. Opponents of the régime were mysteriously killed.

In 1934, Trujillo, who had promoted himself to generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

of the army, was up for re-election. By then, there was no organized opposition left in the country, and he was elected as the sole candidate on the ballot. In addition to the widely rigged (and regularly uncontested) elections, he instated "civic reviews", with large crowds shouting their loyalty to the government, which would in turn create more support for Trujillo.

Personality cult

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

to Ciudad Trujillo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

. The province of San Cristóbal was renamed to "Trujillo" and the nation's highest peak, Pico Duarte

Pico Duarte is the highest peak in the Dominican Republic, on the island of Hispaniola and in all the Caribbean. At above sea level, it gives the Dominican Republic the 16th-highest maximum elevation of any island in the world. Additionally, it ...

, to Pico Trujillo

Pico Duarte is the highest peak in the Dominican Republic, on the island of Hispaniola and in all the Caribbean. At above sea level, it gives the Dominican Republic the 16th-highest maximum elevation of any island in the world. Additionally, it ...

. Statues of "El Jefe" were mass-produced and erected across the Dominican Republic, and bridges and public buildings were named in his honor. The nation's newspapers had praise for Trujillo as part of the front page, and license plates included slogans such as "¡Viva Trujillo!" and "Año Del Benefactor De La Patria" (Year of the Benefactor of the Nation). An electric sign was erected in Ciudad Trujillo so that "Dios y Trujillo" could be seen at night as well as in the day. Eventually, even churches were required to post the slogan "Dios en cielo, Trujillo en tierra" (God in Heaven, Trujillo on Earth). As time went on, the order of the phrases was reversed (Trujillo on Earth, God in Heaven). Trujillo was recommended for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

by his admirers, but the committee declined the suggestion.

Trujillo was eligible to run again in 1938, but, citing the United States example of two presidential terms, he stated, "I voluntarily, and against the wishes of my people, refuse re-election to the high office." In fact, a vigorous re-election campaign had been launched in the middle of 1937 but the international uproar that followed the Haitian massacre later that year forced Trujillo to announce his "return to private life." Consequently, the Dominican Party nominated Trujillo's handpicked successor, 61-year-old vice-president Jacinto Peynado, with Manuel de Jesús Troncoso his running mate. They appeared alone on the ballot in the 1938 election. Trujillo kept his positions as generalissimo of the army and leader of the Dominican Party. It was understood that Peynado was merely a puppet, and Trujillo still held all governing power in the nation. Peynado increased the size of the electric "Dios y Trujillo" sign and died on 7 March 1940, with Troncoso serving out the rest of the term. However, in 1942, with US President Franklin Roosevelt having run for a third term in the United States, Trujillo ran for president again and was elected unopposed. He served for two terms, which he lengthened to five years each. In 1952, under pressure from the Organization of American States, he ceded the presidency to his brother,

Trujillo was eligible to run again in 1938, but, citing the United States example of two presidential terms, he stated, "I voluntarily, and against the wishes of my people, refuse re-election to the high office." In fact, a vigorous re-election campaign had been launched in the middle of 1937 but the international uproar that followed the Haitian massacre later that year forced Trujillo to announce his "return to private life." Consequently, the Dominican Party nominated Trujillo's handpicked successor, 61-year-old vice-president Jacinto Peynado, with Manuel de Jesús Troncoso his running mate. They appeared alone on the ballot in the 1938 election. Trujillo kept his positions as generalissimo of the army and leader of the Dominican Party. It was understood that Peynado was merely a puppet, and Trujillo still held all governing power in the nation. Peynado increased the size of the electric "Dios y Trujillo" sign and died on 7 March 1940, with Troncoso serving out the rest of the term. However, in 1942, with US President Franklin Roosevelt having run for a third term in the United States, Trujillo ran for president again and was elected unopposed. He served for two terms, which he lengthened to five years each. In 1952, under pressure from the Organization of American States, he ceded the presidency to his brother, Héctor

Hector () is an English, French, Scottish, and Spanish given name. The name is derived from the name of Hektor, a legendary Trojan champion who was killed by the Greek Achilles. The name ''Hektor'' is probably derived from the Greek ''ékhein'', m ...

. Despite being officially out of power, Rafael Trujillo organized a major national celebration to commemorate 25 years of his rule in 1955. Gold and silver commemorative coins were minted with his image.

Oppression

Brutal oppression of actual or perceived members of the opposition was the key feature of Trujillo's rule from the very beginning in 1930 when his gang, "The 42", led by Miguel Angel Paulino, drove through the streets in their red Packard "''carro de la muerte''" ("car of death"). Trujillo also maintained an execution list of people throughout the world who he felt were his direct enemies or who he felt had wronged him. He even once allowed an opposition party to form and permitted it to operate legally and openly, mainly so that he could identify those who opposed him and arrest or kill them. Imprisonments and killings were later handled by the SIM, theServicio de Inteligencia Militar

The Servicio de Inteligencia Militar (SIM) (English: Military Intelligence Service) was the main secret police force and death squad during the later part of the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo to keep control within the Dominican Republic.

Operat ...

, efficiently organized by Johnny Abbes, who operated in Cuba, Mexico, Guatemala, New York, Costa Rica, and Venezuela. Some cases reached international notoriety such as the disappearance of Jesús de Galíndez and the murder of the Mirabal sisters

The Mirabal sisters ( es, hermanas Mirabal ) were four sisters from the Dominican Republic, three of whom (Patria, Minerva and María Teresa) opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo () and were involved in clandestine activities against his ...

, which further eroded Trujillo's critical support by the US government. After Trujillo approved an assassination attempt on the Venezuelan President Rómulo Ernesto Betancourt Bello, the Organization of American States and the United States blocked Trujillo's access to US sugar quota profits.

Immigration

Trujillo was known for his open-door policy, acceptingJewish refugees

This article lists expulsions, refugee crises and other forms of displacement that have affected Jews.

Timeline

The following is a list of Jewish expulsions and events that prompted significant streams of Jewish refugees.

Assyrian captivity

; ...

from Europe, Japanese migration during the 1930s, and exiles from Spain following its civil war. At the 1938 Évian Conference

The Évian Conference was convened 6–15 July 1938 at Évian-les-Bains, France, to address the problem of German and Austrian Jewish refugees wishing to flee persecution by Nazi Germany. It was the initiative of United States President Franklin ...

the Dominican Republic was the only country willing to accept many Jews and offered to accept up to 100,000 refugees on generous terms. In 1940 an agreement was signed and Trujillo donated of his properties for settlements. The first settlers arrived in May 1940; eventually, some 800 settlers came to Sosúa

Sosúa is a beach town in the Puerto Plata province of the Dominican Republic. Located approximately from the Gregorio Luperón International Airport in San Felipe de Puerto Plata.

The town is divided into three sectors: ''El Batey'', which i ...

and most moved later on to the United States.

Refugees from Europe broadened the Dominican Republic's tax base and added more whites to the predominantly mixed-race nation. Trujillo’s government favored white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

refugees over others while Dominican troops expelled illegal immigrants, resulting in the 1937 Parsley Massacre

The Parsley massacre (Spanish: ''el corte'' "the cutting"; Creole: ''kout kouto-a'' "the stabbing") (french: Massacre du Persil; es, Masacre del Perejil; ht, Masak nan Pèsil) was a mass killing of Haitians living in the Dominican Republic's nor ...

of Haitian migrants.

Environmental policy

The Trujillo regime greatly expanded the Vedado del Yaque, a nature reserve around theYaque del Sur River

The Yaque del Sur River (Spanish, ''Río Yaque del Sur'') is a river in the southwestern Dominican Republic. It is approximately 183 km in length.

Etymology

''Yaque'' or ''Yaqui'' was a Taíno word given to two rivers in the Dominican Republ ...

. In 1934 he banned the slash-and-burn

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a farming method that involves the cutting and burning of plants in a forest or woodland to create a field called a swidden. The method begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The downed veget ...

method of clearing land for agriculture, set up a forest warden agency to protect the park system, and banned the logging of pine trees without his permission. In the 1950s the Trujillo regime commissioned a study on the hydroelectric potential of damming the Dominican Republic's waterways. The commission concluded that only forested waterways could support hydroelectric dam

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined an ...

s, so Trujillo banned logging in potential river watersheds. After his assassination in 1961, logging resumed in the Dominican Republic. Squatters burned down the forests for agriculture, and logging companies clear-cut parks. In 1967, President Joaquín Balaguer

Joaquín Antonio Balaguer Ricardo (1 September 1906 – 14 July 2002) was a Dominican politician, scholar, writer, and lawyer. He was President of the Dominican Republic serving three non-consecutive terms for that office from 1960 to 196 ...

launched military strikes against illegal logging.

Trujillo encouraged foreign investment in the Dominican Republic, particularly from Americans. He gave a concession with mineral rights in the Azua Basin to Clem S. Clarke, an oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

man from Shreveport, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

.

Foreign policy

Trujillo tended toward peaceful coexistence with the

Trujillo tended toward peaceful coexistence with the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Trujillo symbolically sided with the Allies and declared war on Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Japan on 11 December 1941. While there was no military participation, the Dominican Republic thus became a founding member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

. Trujillo encouraged diplomatic and economic ties with the United States, but his policies often caused friction with other nations of Latin America, especially Costa Rica and Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

. He maintained friendly relations with Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

of Spain, Perón of Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, and Somoza

The Somoza family ( es, Familia Somoza) is a former political family that ruled Nicaragua for forty-three years from 1936 to 1979. Their family dictatorship was founded by Anastasio Somoza García and was continued by his two sons Luis Somoza D ...

of Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

. Towards the end of his rule, his relationship with the United States deteriorated.

Hull–Trujillo Treaty

Early on, Trujillo determined that Dominican financial affairs had to be put in order, and that included ending the United States's role as collector of Dominican customs—a situation that had existed since 1907 and was confirmed in a 1924 convention signed at the end of the occupation. Negotiations started in 1936 and lasted four years. On 24 September 1940, Trujillo and the American Secretary of State Cordell Hull signed the Hull–Trujillo Treaty, whereby the United States relinquished control over the collection and application of customs revenues, and the Dominican Republic committed to deposit consolidated government revenues in a special bank account to guarantee repayment of foreign debt. The government was free to set custom duties with no restrictions. This diplomatic success gave Trujillo the occasion to launch a massive propaganda campaign that presented him as the savior of the nation. A law proclaimed that the ''Benefactor'' was also now the ''Restaurador de la independencia financiera de la Republica'' (Restorer of the Republic's financial independence).Haiti

Haiti had historically

Haiti had historically occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

what is now the Dominican Republic from 1822 to 1844. Encroachment by Haiti was an ongoing process, and when Trujillo took over, specifically the northwestern border region had become increasingly "Haitianized". The border was poorly defined. In 1933, and again in 1935, Trujillo met the Haitian President Sténio Vincent to settle the border issue. By 1936, they reached and signed a settlement. At the same time, Trujillo plotted against the Haitian government by linking up with General Calixte, Commander of the Garde d'Haiti, and Élie Lescot

Antoine Louis Léocardie Élie Lescot (December 9, 1883 – October 20, 1974) was the President of Haiti from May 15, 1941 to January 11, 1946. He was a member of the country's mixed-race elite. He used the political climate of World War II to s ...

, at that time the Haitian ambassador in Ciudad Trujillo (Santo Domingo). After the settlement, when further border incursions occurred, Trujillo initiated the Parsley Massacre

The Parsley massacre (Spanish: ''el corte'' "the cutting"; Creole: ''kout kouto-a'' "the stabbing") (french: Massacre du Persil; es, Masacre del Perejil; ht, Masak nan Pèsil) was a mass killing of Haitians living in the Dominican Republic's nor ...

.

Parsley massacre

Known as ''La Masacre del Perejil'' in Spanish, the massacre was started by Trujillo in 1937. Claiming that Haiti was harboring his former Dominican opponents, he ordered an attack on the border that slaughtered tens of thousands of Haitians as they tried to escape. The number of dead is still unknown, but it is now calculated between 12,000 and 30,000. The Dominican military used machetes to murder and decapitate many of the victims; they also took people to the port of Montecristi, where many victims were thrown into the sea to drown with their hands and feet bound. The Haitian response was muted, but its government eventually called for an international investigation. Under pressure from Washington, Trujillo agreed to a reparation settlement in January 1938 of US$750,000. By the next year, the amount had been reduced to US$525,000 (US$ million in ); 30 dollars per victim, of which only two cents were given to survivors because of corruption in the Haitian bureaucracy. In 1941, Lescot, who had received financial support from Trujillo, succeeded Vincent as President of Haiti. Trujillo expected that Lescot would be his puppet, but Lescot turned against him. Trujillo unsuccessfully tried to assassinate him in a 1944 plot and then published their correspondence to discredit him. Lescot fled into exile in 1946 after demonstrations against him.Cuba

In 1947, Dominican exiles, including Juan Bosch, had concentrated in Cuba. With the approval and support of Cuba's government, led byRamón Grau

Ramón Grau San Martín (13 September 1881 in La Palma, Pinar del Río Province, Spanish Cuba – 28 July 1969 in Havana, Cuba) was a Cuban physician who served as President of Cuba from 1933 to 1934 and from 1944 to 1948. He was the last pres ...

, an expeditionary force was trained with the intention of invading the Dominican Republic and overthrowing Trujillo. However, international pressure, including from the United States, made the exiles abort the expedition. In turn, when Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

was in power, Trujillo initially supported anti-Batista supporters of Carlos Prío Socarrás

Carlos Manuel Prío Socarrás (July 14, 1903 – April 5, 1977) was a Cuban politician. He served as the President of Cuba from 1948 until he was deposed by a military coup led by Fulgencio Batista on March 10, 1952, three months before new ele ...

in Oriente Province in 1955; however, weapons Trujillo sent were soon inherited by Fidel Castro's insurgents when Prío allied with Castro; Dominican-made Cristóbal carbines and hand grenades became the rebels' standard weapons.

After 1956, when Trujillo saw that Castro was gaining ground, he started to support Batista with money, planes, equipment, and men. Trujillo, convinced that Batista would prevail, was very surprised when Batista showed up as a fugitive after he had been ousted. Trujillo kept Batista until August 1959 as a "virtual prisoner". Only after paying US$3–4 million could Batista leave for Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, which had granted him a visa.

Castro made threats to overthrow Trujillo, and Trujillo responded by increasing the budget for national defense. A foreign legion was formed to defend Haiti, as it was expected that Castro might invade the Haitian part of the island first and remove François Duvalier as well. A Cuban plane with 56 fighting men landed near Constanza, Dominican Republic, on Sunday, 14 June 1959, and six days later more invaders brought by two yachts landed at the north coast. However, the Dominican Army prevailed.

In turn, in August 1959, Johnny Abbes attempted to support an anti-Castro group led by Escambray near Trinidad, Cuba

Trinidad () is a town in the province of Sancti Spíritus, central Cuba. Together with the nearby Valle de los Ingenios, it has been a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1988, because of its historical importance as a center of the sugar trade in ...

. The attempt, however, was thwarted when Cuban troops surprised a plane he had sent when it was unloading its cargo.

Betancourt assassination attempt

By the late 1950s, opposition to Trujillo's regime was starting to build to a fever pitch, especially among a younger generation who had no memory of the poverty and instability that had preceded the dictatorship. Many clamored for democratization. The Trujillo regime responded with greater repression. The Military Intelligence Service (SIM) secret police, led by Johnny Abbes, remained as ubiquitous as before. Other nations ostracized the Dominican Republic, compounding the dictator's paranoia.

Trujillo began to interfere more and more in the domestic affairs of neighboring countries. He expressed great contempt for Venezuela's president

By the late 1950s, opposition to Trujillo's regime was starting to build to a fever pitch, especially among a younger generation who had no memory of the poverty and instability that had preceded the dictatorship. Many clamored for democratization. The Trujillo regime responded with greater repression. The Military Intelligence Service (SIM) secret police, led by Johnny Abbes, remained as ubiquitous as before. Other nations ostracized the Dominican Republic, compounding the dictator's paranoia.

Trujillo began to interfere more and more in the domestic affairs of neighboring countries. He expressed great contempt for Venezuela's president Rómulo Betancourt

Rómulo Ernesto Betancourt Bello (22 February 1908 – 28 September 1981; ), known as "The Father of Venezuelan Democracy", was the president of Venezuela, serving from 1945 to 1948 and again from 1959 to 1964, as well as leader of Acción De ...

; an established and outspoken opponent of Trujillo, Betancourt associated with Dominicans who had plotted against the dictator. Trujillo developed an obsessive personal hatred of Betancourt and supported numerous plots by Venezuelan exiles to overthrow him. This pattern of intervention led the Venezuelan government to take its case against Trujillo to the Organization of American States (OAS), a move that infuriated Trujillo, who ordered his agents to plant a bomb in Betancourt's car. The assassination attempt, carried out on Friday, 24 June 1960, injured but did not kill the Venezuelan president.

The Betancourt incident inflamed world opinion against Trujillo. Outraged OAS members voted unanimously to sever diplomatic relations with his government and impose economic sanctions on the Dominican Republic. The brutal murder on Friday, 25 November 1960, of the three Mirabal sisters

The Mirabal sisters ( es, hermanas Mirabal ) were four sisters from the Dominican Republic, three of whom (Patria, Minerva and María Teresa) opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo () and were involved in clandestine activities against his ...

, Patria, María Teresa and Minerva, who opposed Trujillo's dictatorship, further increased discontent with his repressive rule. The dictator had become an embarrassment to the United States, and relations became especially strained after the Betancourt incident.

Personal life

Trujillo's "central arch" was his instinct for power. This was coupled with an intense desire for money, which he recognized as a source of and support for power. Up at four in the morning, he exercised, studied the newspaper, read many reports, and completed papers before breakfast. At the office by nine, he continued his work, and took lunch by noon. After a walk, he continued to work until 7:30 pm. After dinner, he attended functions, held discussions, or was driven around incognito in the city "observing and remembering." UntilSanto Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

's National Palace was built in 1947, he worked out of the Casas Reales, the colonial-era Viceregal

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

center of administration. Today the building is a museum; on display are his desk and chair, along with a massive collection of arms and armor that he bought. He was methodical, punctual, secretive, and guarded; he had no true friends, only associates and acquaintances. For his associates, his actions towards them were unpredictable.

Trujillo and his family amassed enormous wealth. He acquired cattle lands on a grand scale, and went into meat and milk production, operations that soon evolved into

Trujillo and his family amassed enormous wealth. He acquired cattle lands on a grand scale, and went into meat and milk production, operations that soon evolved into monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

. Salt, sugar, tobacco, lumber, and the lottery were other industries that he or his family members dominated. Family members also received positions within the government and the army, including one of Trujillo's sons who was made a colonel in the Dominican Army when he was only four years old. Two of Trujillo's brothers, Héctor and José Arismendy, also held positions in his government. José Arismendy Trujillo oversaw the creation of the main radio station, ''La Voz Dominicana'', and later the television station, the fourth in the Caribbean.

By 1937 Trujillo's annual income was about $1.5 million ($ million in ); at the time of his death the state took over 111 Trujillo-owned companies. His love of fine and ostentatious clothing was displayed in elaborate uniforms and suits, of which he collected almost two thousand. Fond of neckties, he amassed a collection of over ten thousand. Trujillo doused himself with perfume and liked gossip.

His sexual appetite was rapacious, and he preferred mulatto women with full bodies.

Trujillo was married three times and kept other women as mistresses. On 13 August 1913, Trujillo married Aminta Ledesma Lachapelle, with whom he had 2 daughters, Julia, who died as an infant, and Flor de Oro, who died of lung cancer in 1978. On 30 March 1927, Trujillo married Bienvenida Ricardo Martínez, a girl from Monte Cristi and the daughter of Buenaventura Ricardo Heureaux. A year later he met María de los Angeles Martínez Alba (nicknamed "''la españolita''", or "the little Spanish girl"), and had an affair with her. He divorced Bienvenida in 1935 and married Martínez. A year later he had a daughter with Bienvenida, named Odette Trujillo Ricardo.

Trujillo's three children with María Martínez were Rafael Leónidas Ramfis, who was born on 5 June 1929, María de los Ángeles del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (Angelita), born in Paris on 10 June 1939, and Leónidas Rhadamés, born on 1 December 1942. Ramfis and Rhadamés were named after characters in Giuseppe Verdi's opera ''Aida

''Aida'' (or ''Aïda'', ) is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni. Set in the Old Kingdom of Egypt, it was commissioned by Cairo's Khedivial Opera House and had its première there on 24 Decemb ...

''.

In 1937, Trujillo met Lina Lovatón Pittaluga, an upper-class debutante with whom he had two children, Yolanda in 1939, and Rafael, born on 20 June 1943.

In spite of Trujillo's indifference to the game of baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

, the dictator invited many black American players to the Dominican Republic, where they received good pay for playing on first-class, un-segregated teams. The great Negro league star Satchel Paige

Leroy Robert "Satchel" Paige (July 7, 1906 – June 8, 1982) was an American professional baseball pitcher who played in Negro league baseball and Major League Baseball (MLB). His career spanned five decades and culminated with his induction in ...

pitched for Los Dragones of Ciudad Trujillo, a team organized by Trujillo. Paige later claimed, jokingly, that his guards positioned themselves "like a firing squad" to encourage him to pitch well. Los Dragones won the 1937 Dominican championship at Estadio Trujillo in Ciudad Trujillo.

Trujillo was energetic and fit. He was generally quite healthy but suffered from chronic lower urinary infections and, later, prostate problems. In 1934, Dr. Georges Marion was called from Paris to perform three urologic procedures on Trujillo.

Over time Trujillo acquired numerous homes. His favorite was ''Casa Caobas'', on ''Estancia Fundacion'' near San Cristóbal. He also used ''Estancia Ramfis'' (which, after 1953, became the Foreign Office), ''Estancia Rhadames'', and a home at Playa de Najayo

Playa (plural playas) may refer to:

Landforms

* Endorheic basin, also known as a sink, alkali flat or sabkha, a desert basin with no outlet which periodically fills with water to form a temporary lake

* Dry lake, often called a ''playa'' in the so ...

. Less frequently he stayed at places he owned in Santiago de los Caballeros

Santiago de los Caballeros (; '' en, Saint James of the Knights''), often shortened to Santiago, is the second-largest city in the Dominican Republic and the fourth-largest city in the Caribbean by population. It is the capital of Santiago Prov ...

, Constanza, La Cumbre, San José de las Matas, and elsewhere. He maintained a penthouse at the ''Embajador Hotel'' in the capital.

While Trujillo was nominally a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, his devotion was limited to a perfunctory role in public affairs; he placed faith in local folk religion

In religious studies and folkloristics, folk religion, popular religion, traditional religion or vernacular religion comprises various forms and expressions of religion that are distinct from the official doctrines and practices of organized re ...

.

He was popularly known as "El Jefe" ("The Chief") or "El Benefactor" ("The Benefactor") but was privately referred to as ''Chapitas'' ("Bottlecaps") because of his indiscriminate wearing of medals. Dominican children emulated Trujillo by constructing toy medals from bottle cap

A bottle cap or bottle top is a closure for the top opening of a bottle. A cap is sometimes colourfully decorated with the logo of the brand of contents. Plastic caps are used for plastic bottles, while metal with plastic backing is used for gl ...

s. He was also known as "El Chivo" ("The Goat").

Assassination

Chevrolet Bel Air

The Chevrolet Bel Air is a full-size car produced by Chevrolet for the 1950–1975 model years. Initially, only the two-door hardtops in the Chevrolet model range were designated with the Bel Air name from 1950 to 1952. With the 1953 model year, ...

was ambushed on a road outside the Dominican capital. He was the victim of an ambush plotted by a number of men, such as General Juan Tomás Díaz, Pedro Livio Cedeño, Antonio de la Maza Antonio de la Maza (May 24, 1912 – June 4, 1961) was a Dominican businessman based in Santo Domingo. He was an opponent of Rafael Trujillo, and was one of the principal conspirators in the assassination of the aforementioned dictator which took ...

, Amado García Guerrero

Amado García Guerrero (June 2, 1931 – June 2, 1961) was one of the conspirators against, and killers of, Dominican dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo.

Assassination of Rafael Trujillo

He was a soldier in the Dominican Republic. A member o ...

and General Antonio Imbert Barrera

Major General Antonio Cosme Imbert Barrera (December 3, 1920 – May 31, 2016) was a two-star army general advitam of the Dominican Army and was President of the Dominican Republic from May to August 1965.

Imbert, who plotted to assassinate d ...

. The plotters, however, failed to take control as the later-executed General José René Román Fernandez ("Pupo Román") betrayed his co-conspirators by his inactivity, and contingency plans had not been made. On the other side, Johnny Abbes, Roberto Figueroa Carrión, and the Trujillo family put the SIM to work to hunt the members of the plot and brought back Ramfis Trujillo

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Martínez (5 June 1929 – 27 December 1969), better known as Ramfis Trujillo Martínez, was the adopted son of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic, after whose 1961 assassination he briefly ...

from Paris to step into his father's shoes. The response by the SIM was swift and brutal. Hundreds of suspects were detained, many tortured. On 18 November the last executions took place when six of the conspirators were executed in the "Hacienda María Massacre". Imbert was the only one of the seven assassins who survived the manhunt. A co-conspirator named Luis Amiama Tio also survived.

US President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

learned of Trujillo's death during a diplomatic meeting with French President Charles de Gaulle.

Trujillo's funeral was that of a statesman with the long procession ending in his hometown of San Cristóbal, where his body was first buried. Dominican President Joaquín Balaguer

Joaquín Antonio Balaguer Ricardo (1 September 1906 – 14 July 2002) was a Dominican politician, scholar, writer, and lawyer. He was President of the Dominican Republic serving three non-consecutive terms for that office from 1960 to 196 ...

gave the eulogy. The efforts of the Trujillo family to keep control of the country ultimately failed. The military uprising on 19 November of the Rebellion of the Pilots and the threat of US intervention set the final stage and ended the Trujillo regime. Ramfis tried to flee with his father's body upon his boat '' Angelita'', but was turned back. Balaguer allowed Ramfis to leave the country and to take his father's body to Paris. There, the remains were interred in the Cimetière du Père Lachaise on 14 August 1964, and six years later moved to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, to the Mingorrubio Cemetery

The Mingorrubio Cemetery ( es, Cementerio de Mingorrubio), also called the Cemetery of El Pardo ( es, Cementerio de El Pardo), is a municipal cemetery on the edge of Madrid, Spain. Mingorrubio is a neighborhood in the northern district of Fuen ...

in El Pardo

El Pardo is a ward (''barrio'') of Madrid belonging to the district of Fuencarral-El Pardo. As of 2008 its population was of 3,656.

History

The ward was first mentioned in 1405 and in 1950 was an autonomous municipality of the Community of Madri ...

on the north side of Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

.

The role of the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

in the killing has been debated. Imbert insisted that the plotters acted on their own. However, Trujillo was certainly murdered with weapons supplied by the CIA.

In a 1975 report to the Deputy Attorney General of the United States

The United States deputy attorney general is the second-highest-ranking official in the United States Department of Justice and oversees the day-to-day operation of the Department. The deputy attorney general acts as attorney general during the ...

, CIA officials described the agency as having "no active part" in the assassination and only a "faint connection" with the groups that planned the killing.

US involvement appears to go deeper than supplying weapons. In the 1950s, the CIA gave José Figueres Ferrer money to publish a political journal, ''Combate'' and to found a left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

school for Latin American opposition leaders. Funds passed from a shell foundation to the Jacob Merrill Kaplan Fund; then to the ''Institute of International Labor Research'' (IILR) headed by Norman Thomas

Norman Mattoon Thomas (November 20, 1884 – December 19, 1968) was an American Presbyterian minister who achieved fame as a socialist, pacifist, and six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America.

Early years

Thomas was the ...

, six-time US presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America; and finally to Figueres, Sacha Volman, and Juan Bosch. Sacha Volman, treasurer of the IILR, was a CIA agent.

Cord Meyer

Cord Meyer Jr. (; November 10, 1920 – March 13, 2001) was a US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) official. After serving in World War II as a Marine officer in the Pacific War, where he was both injured and decorated, he led the United World Fe ...

was a CIA official responsible for manipulating international groups. He used the contacts with Bosch, Volman, and Figueres for a new purpose, as the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

moved to rally the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the te ...

against Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

's Fidel Castro, Trujillo had become expendable. Dissidents inside the Dominican Republic argued that assassination was the only certain way to remove Trujillo.

According to Chester Bowles

Chester Bliss Bowles (April 5, 1901 – May 25, 1986) was an American diplomat and ambassador, governor of Connecticut, congressman and co-founder of a major advertising agency, Benton & Bowles, now part of Publicis Groupe. Bowles is best known ...

, the Undersecretary of State, internal Department of State discussions in 1961 on the topic were vigorous. Richard N. Goodwin, Assistant Special Counsel to the President, who had direct contacts with the rebel alliance, argued for intervention against Trujillo. Quoting Bowles directly: ''The next morning I learned that in spite of the clear decision against having the dissident group request our assistance Dick Goodwin following the meeting sent a cable to CIA people in the Dominican Republic without checking with State or CIA; indeed, with the protest of the Department of State. The cable directed the CIA people in the Dominican Republic to get this request at any cost. When Allen Dulles found this out the next morning, he withdrew the order. We later discovered it had already been carried out.''

An internal CIA memorandum

A memorandum ( : memoranda; abbr: memo; from the Latin ''memorandum'', "(that) which is to be remembered") is a written message that is typically used in a professional setting. Commonly abbreviated "memo," these messages are usually brief and ...

states that a 1973 Office of Inspector General

In the United States, Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a generic term for the oversight division of a federal or state agency aimed at preventing inefficient or unlawful operations within their parent agency. Such offices are attached to ma ...

investigation into the murder disclosed "quite extensive Agency involvement with the plotters." The CIA described its role in "changing" the government of the Dominican Republic "as a 'success' in that it assisted in moving the Dominican Republic from a totalitarian dictatorship to a Western-style democracy."

Juan Bosch, the earlier recipient of CIA funding, was elected president of the Dominican Republic in 1962 and was deposed in 1963.

Even after the death of Trujillo, the unusual events continued. In November 1961, Mexican police found a corpse they identified as Luis Melchior Vidal, Jr., godson of Trujillo. Vidal was the unofficial business agent of the Dominican Republic while Trujillo was in power. Under the cover of the American Sucrose Company and the Paint Company of America, Vidal had teamed up with an American, Joel David Kaplan, to operate as arms merchants for the CIA.

Joel David Kaplan was the nephew of the previously mentioned Jacob Merrill Kaplan. The elder Kaplan earned his fortune primarily through operations in Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

In 1962, the younger Kaplan was convicted of killing Vidal, in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital city, capital and primate city, largest city of Mexico, and the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North Amer ...

. He was sentenced to 28 years in prison. Kaplan escaped from a Mexican prison using a helicopter. The dramatic event was the basis for the Charles Bronson action film

Action film is a film genre in which the protagonist is thrust into a series of events that typically involve violence and physical feats. The genre tends to feature a mostly resourceful hero struggling against incredible odds, which include l ...

'' Breakout''.

The Mexican police requested for the FBI to arrest and remand Joel Kaplan on 20 August 1971. Kaplan's attorney claimed that Kaplan was a CIA agent. Neither the FBI nor the US Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United Stat ...

has pursued the issue. The Mexican government never initiated extradition proceedings against Kaplan.

Honors and awards

*Legion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

* Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem

The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Equestris Sancti Sepulcri Hierosolymitani, links=yes, OESSH), also called Order of the Holy Sepulchre or Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, is a Catholic order of knighthood under ...

/ref>

In media

See also

* * *Explanatory notes

References

Citations

General bibliography

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * Cadeau, Sabine F. 2022. ''More than a Massacre: Racial Violence and Citizenship in the Haitian–Dominican Borderlands''. Cambridge University Press. * Hougan, Jim''Spooks: The Haunting of America & the Private Use of Secret Agents''

(

non-fiction

Nonfiction, or non-fiction, is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to provide information (and sometimes opinions) grounded only in facts and real life, rather than in imagination. Nonfiction is often associated with b ...

). New York: William Morrow (1978). .

* López-Calvo, Ignacio, ''"God and Trujillo": Literary and Cultural Representations of the Dominican Dictator''. University Press of Florida

The University Press of Florida (UPF) is the scholarly publishing arm of the State University System of Florida, representing Florida's twelve state universities. It is located in Gainesville near the University of Florida, one of the state's majo ...

(2005). .

"GENERALISIMO E.N., RAFAEL LEONIDAS TRUJILLO MOLINA."

Secretario de Estado de las Fuerzas Armadas. * Timoneda, Joan C. "Institutions as Signals: How Dictators Consolidate Power in Times of Crisis." ''Comparative Politics'', vol. 53, no. 1 (2020), pp. 49–68. * Turits, Richard Lee. ''Foundations of Despotism: Peasants, the Trujillo Regime, and Modernity in Dominican History''. Stanford University Press (2004). .

External links

*Biography

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Trujillo Molina, Rafael 1891 births 1961 deaths 1961 murders in North America Anti-Masonry Assassinated Dominican Republic politicians Assassinated heads of state Assassinated people Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Burials at Mingorrubio Cemetery Deaths by firearm in the Dominican Republic Dominican Party politicians Dominican Republic anti-communists Dominican Republic military personnel Dominican Republic people of Canarian descent Dominican Republic people of French descent Dominican Republic people of Haitian descent Dominican Republic people of Spanish descent Dominican Republic Roman Catholics Generalissimos Genocide perpetrators Grand Crosses Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany People from San Cristóbal, Dominican Republic People killed in Central Intelligence Agency operations People of the Cold War Politicide perpetrators Presidents of the Dominican Republic Recipients of the Legion of Honour World War II political leaders Far-right politics in South America