Rafael Celestino Benítez on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rear Admiral Rafael Celestino Benítez (March 9, 1917 – March 6, 1999) was a highly decorated American submarine commander who led the rescue effort of the crew members of the during the Cold War. After retiring from the navy, he was

/ref>Rafael Celestino Benítez: Navy Hero

/ref>

The ''Cochino'' suffered two casualties, Lt. Cmdr. Richard M. Wright, who survived despite the fact that he was severely burned, and Robert Philo, a civilian

The ''Cochino'' suffered two casualties, Lt. Cmdr. Richard M. Wright, who survived despite the fact that he was severely burned, and Robert Philo, a civilian

Pan American World Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

' vice president for Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

. He taught international law for 16 years at the University of Miami School of Law

The University of Miami School of Law (Miami Law or UM Law) is the law school of the University of Miami, a private research university in Coral Gables, Florida.

Founded in 1926, the University of Miami School of Law is the oldest law school i ...

, and served as associate dean, interim dean and director and founder of the foreign graduate law program. While there, he founded the comparative law LL.M. program, the inter-American law LL.M. program, and the ''Inter-American Law Review''. After his death, the university established a scholarship in his memory to benefit a foreign attorney who is enrolled in one of the Law School's LL.M. programs.

Early years

Benítez was born inJuncos, Puerto Rico

Juncos (, ) is a town and one of the 78 municipalities of Puerto Rico. It is located in the eastern central region of the island to the west of the Caguas Valley, south of Canóvanas and Carolina; southeast of Gurabo; east of San Lorenzo; an ...

, where he received his primary and secondary education. After he finished high school, he was accepted in the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

by appointment of the Honorable Santiago Iglesias

Santiago Iglesias Pantín (February 22, 1872 – December 5, 1939), was a Spanish-born Puerto Rican socialist and trade union activist. Iglesias is best remembered as a leading supporter of statehood for Puerto Rico, and as the Resident Commi ...

, Puerto Rico's Resident Commissioner. He graduated from the academy in 1939 and was assigned to submarine duty.Naval History and Heritage Command/ref>Rafael Celestino Benítez: Navy Hero

/ref>

World War II

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Benítez saw action aboard the submarines USS ''Dace'' (SS-247) and USS ''Grenadier'' (SS-210) and on various occasions weathered depth charge attacks. For his actions, he was awarded the Silver Star twice and the Bronze Star Medal.

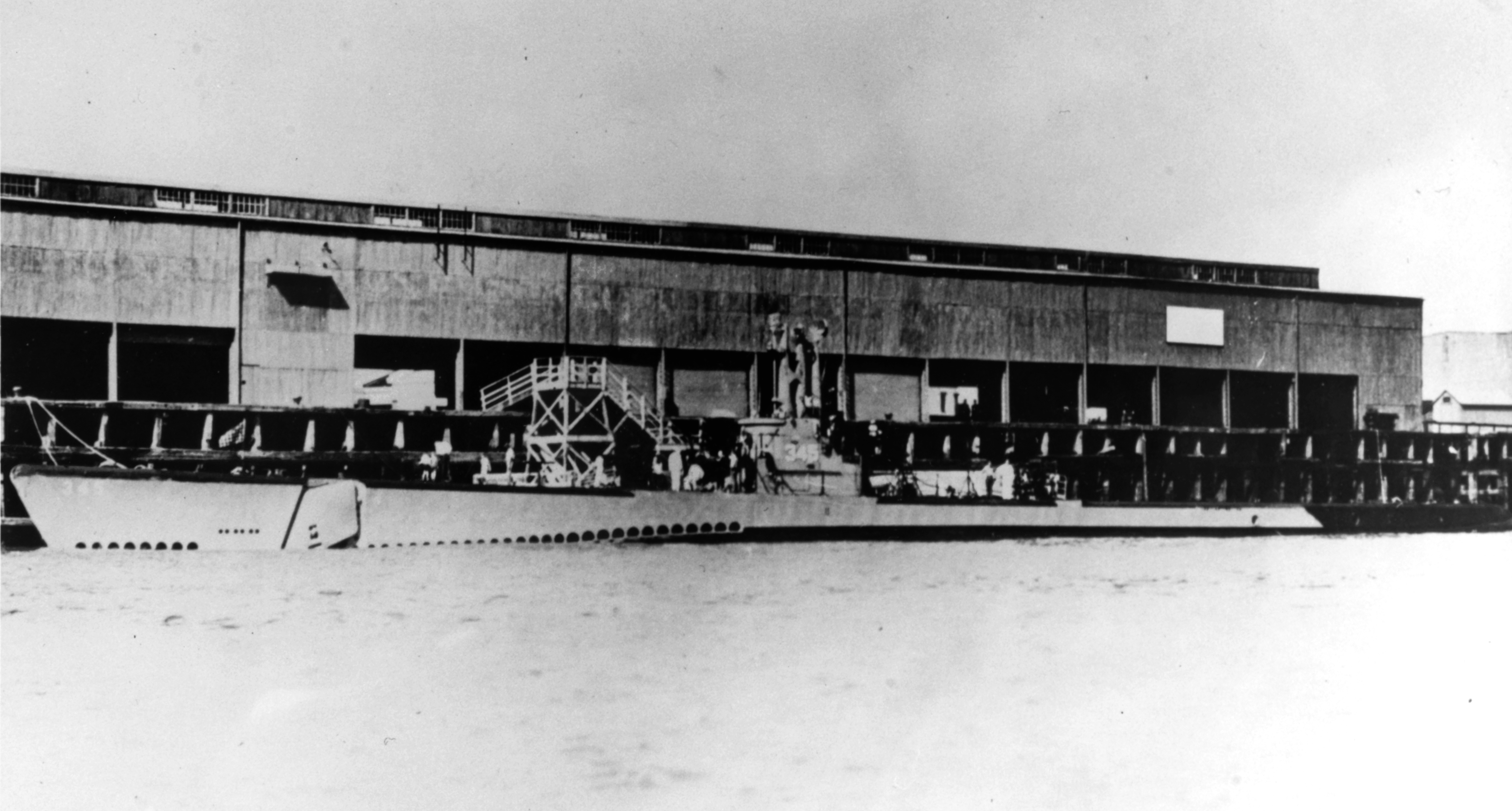

He served as commanding officer (with the rank of lieutenant commander) of the submarine USS Halibut (SS-232) from February 15, 1945, to May 19, 1945. The Halibut was the first ship of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

to be named for the halibut

Halibut is the common name for three flatfish in the genera '' Hippoglossus'' and '' Reinhardtius'' from the family of right-eye flounders and, in some regions, and less commonly, other species of large flatfish.

The word is derived from ''h ...

, a large species of flatfish. She was launched on December 3, 1941, and commissioned on April 10, 1942. The ''Halibut'' had an impressive war record, which included sinking 12 Japanese ships, but was damaged beyond reasonable repair on her tenth and final war patrol, which ended on December 1, 1944. Benítez's only mission as commander of the ''Halibut'' was to bring her from San Francisco to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where she was decommissioned on July 18, 1945.

Post war

On January 29, 1946, Lieutenant Commander Benítez was given command of the . Benítez, inspired by his father who was a judge, attendedGeorgetown Law School

The Georgetown University Law Center (Georgetown Law) is the law school of Georgetown University, a private research university in Washington, D.C. It was established in 1870 and is the largest law school in the United States by enrollment and ...

and earned his law degree in June 1949.Sontag, ''Blind Man's Bluff''.

''Cochino'' incident

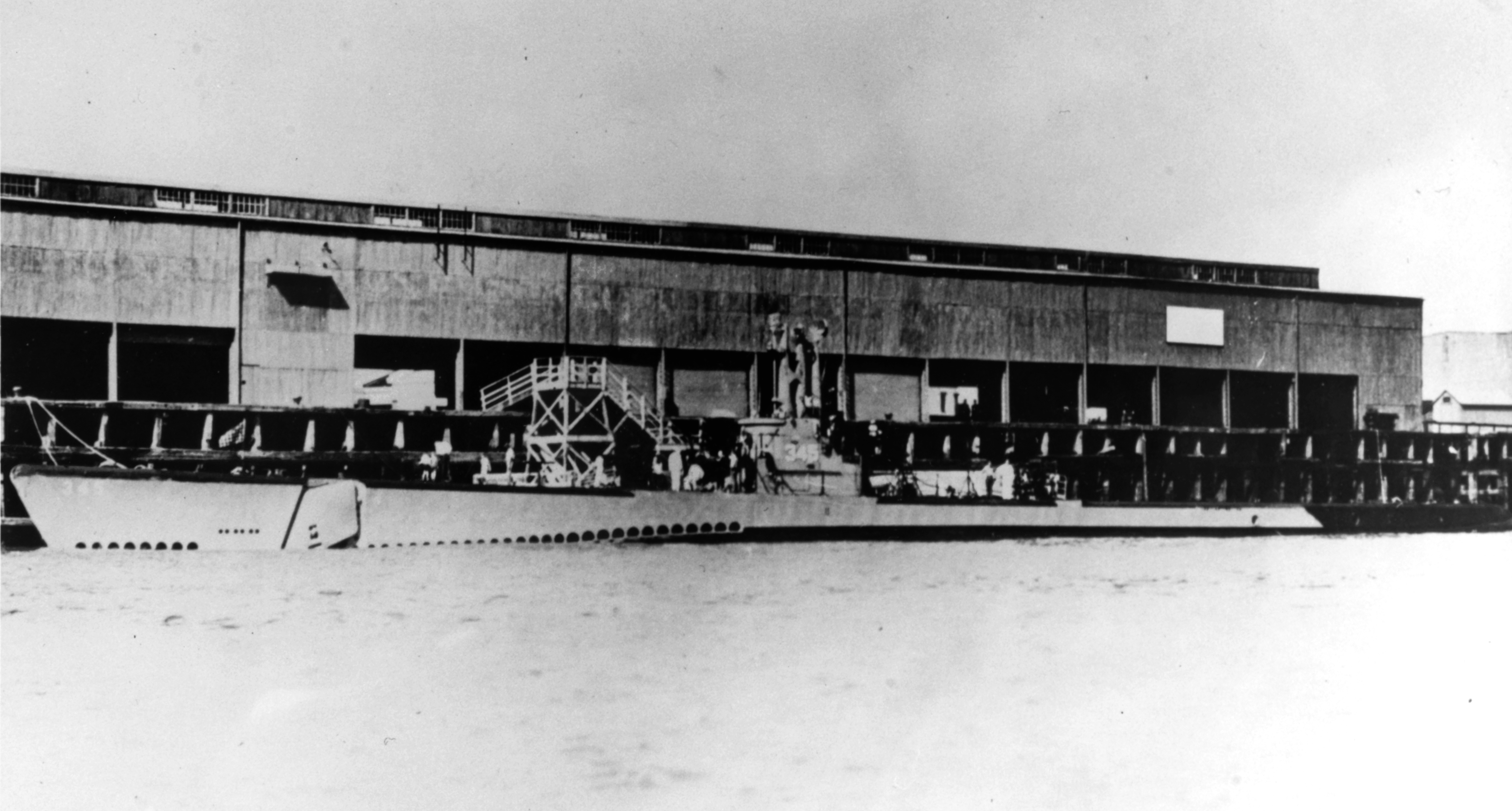

During the latter part of 1949, early in the Cold War Era, Benítez was given the command of the submarine USS ''Cochino''. On August 12, 1949, the ''Cochino'', along with the USS ''Tusk'', departed from the harbor ofPortsmouth, England

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. Both diesel submarines were reported to be on a cold-water training mission. However, according to '' Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage'', the submarines – equipped with snorkels that allowed them to spend long periods underwater, largely invisible to an enemy, and with electronic gear designed to detect far-off radio signals – were part of an American intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can be des ...

operation.

The mission of the ''Cochino'' and ''Tusk'' was to eavesdrop on communications that revealed the testing of submarine-launched Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

missiles that might soon carry nuclear warhead

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s. This was the first American undersea spy mission of the cold war.

On August 25, one of the ''Cochinos 4,000-pound batteries caught fire, emitting hydrogen gas and smoke. Unable to receive any help from the ''Tusk'', Commander Benítez directed the firefighting. He ordered the ''Cochino'' to surface and had dozens of crew members lash themselves to the deck rails with ropes while others fought the blaze. Benítez tried to save his ship and at the same time save his men from the toxic gases. He realized that the winds were about to tear the ropes and ordered his men to form a pyramid on the ship's open bridge, which was designed to hold seven men.

The ''Cochino'' suffered two casualties, Lt. Cmdr. Richard M. Wright, who survived despite the fact that he was severely burned, and Robert Philo, a civilian

The ''Cochino'' suffered two casualties, Lt. Cmdr. Richard M. Wright, who survived despite the fact that he was severely burned, and Robert Philo, a civilian sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on o ...

expert, who attempted to reach the ''Tusk'' on a raft to report on the conditions of the ''Cochino'', but was knocked overboard along with 11 of the ''Tusks crew members. As a result, Philo and six of the ''Tusk''s crew perished.

The ocean waters became calmer during the night and the ''Tusk'' was able to approach the ''Cochino''. All of the crew, with the exception of Commander Benítez, boarded the ''Tusk''. Finally, the crew members of the ''Tusk'' convinced Benítez to board the ''Tusk'', which he did two minutes before the ''Cochino'' sank off the coast of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

.

Aftermath of the ''Cochino'' incident

According to the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' of April 5, 1997, "On September 20, 1949, the Soviet publication ''Red Fleet'' said the ''Cochino'' had been "not far from Murmansk

Murmansk (Russian: ''Мурманск'' lit. "Norwegian coast"; Finnish: ''Murmansk'', sometimes ''Muurmanski'', previously ''Muurmanni''; Norwegian: ''Norskekysten;'' Northern Sámi: ''Murmánska;'' Kildin Sámi: ''Мурман ланнҍ'') ...

" and suggested that it had been seeking military information. On September 23, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, confirming fears that had led to Commander Benitez's mission, announced that the Soviet Union had detonated its first nuclear device".

Late career

In 1952, Benítez was named chief of the United States naval mission toCuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, a position which he held until 1954. In 1955, Benítez was given the command of the destroyer . The ''Waldron'' resumed normal operations along the East Coast and in the West Indies under his command after having completed a circumnavigation of the globe.

Post-Navy career

Benítez retired from the Navy in 1959 and was promoted to the rank of rear admiral as he had been decorated for heroism in combat. He becamePan American World Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

' vice president for Latin America. He taught international law and was associate dean at the University of Miami Law School and dean of the university's graduate school of international studies. During his years at University of Miami Law School, Benítez founded the Graduate Program for Foreign Lawyers, now known as the LL.M. Program in Comparative Law. He also inaugurated the ''"Lawyer of the Americas"'' (the predecessor of the Inter-American Law Review) and started the Masters Program in Inter-American Law for U.S. Lawyers.

In 1978, he served as a board member of the US Foundation of the University of the Valley of Guatemala, located in Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

. Benítez was also the author of ''Anchors'' (), a compilation of ethical and practical maxims, published in August 1996. On March 15, 2000, the University of Miami School of Law launched a Rafael C. Benítez Scholarship Fund to support the studies of foreign graduate students.

Benítez resided in Easton, Maryland, with his wife and three children, a son and two daughters. On March 6, 1999, he died at the Memorial Hospital located in Easton. He was buried with full military honors at Oxford Cemetery in Talbot County, Maryland.

Silver Star and Bronze Star citations

Awards and recognitions

Among Rear Admiral Benítez's decorations and medals were the following:See also

*Hispanic Admirals in the United States Navy

Hispanic and Latino Admirals in the United States Navy can trace their tradition of naval military service to the Latino sailors, who have served in the Navy in every war and conflict since the American Revolution. Prior to the Civil War, the high ...

* List of Puerto Ricans

*Puerto Ricans in World War II

Puerto Ricans and people of Puerto Rican descent have participated as members of the United States Armed Forces in the American Civil War and in every conflict which the United States has been involved since World War I. In World War II, more tha ...

*List of Puerto Rican military personnel

Throughout history Puerto Ricans, including people of Puerto Rican descent, have gained notability as members of the military. They have served and have fought for many countries, such as Canada, Cuba, England, Mexico, Spain, the United States an ...

*Hispanics in the United States Navy

Hispanics in the United States Navy can trace their tradition of naval military service to men such as Lieutenant Jordi Farragut Mesquida, who served in the American Revolution. Hispanics, such as Seaman Philip Bazaar and Seaman John Ortega, ha ...

* Hispanics in the United States Naval Academy

References

Further reading

*"Puertorriquenos Who Served With Guts, Glory, and Honor. Fighting to Defend a Nation Not Completely Their Own"; by : Greg Boudonck; ; * * *External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Benitez, Rafael Celestino 1917 births 1999 deaths United States Navy personnel of World War II People from Juncos, Puerto Rico Puerto Rican academics Puerto Rican military officers Puerto Rican United States Navy personnel Recipients of the Silver Star University of Miami faculty United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy rear admirals (upper half) United States submarine commanders