Quinta de Olivos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

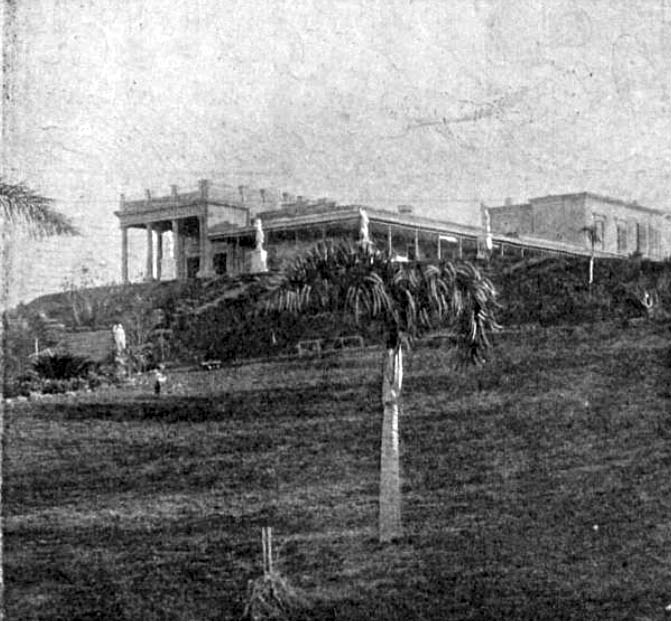

The Quinta presidencial de Olivos, also known as Quinta de Olivos, is an architectural landmark in the north side

The Quinta presidencial de Olivos, also known as Quinta de Olivos, is an architectural landmark in the north side

/ref>

Azcuénaga inherited the land on the death of his wife in 1829, and their son, Miguel José, in turn inherited it in 1833. He converted the property into an equestrian estate, though the rise of

Azcuénaga inherited the land on the death of his wife in 1829, and their son, Miguel José, in turn inherited it in 1833. He converted the property into an equestrian estate, though the rise of

/ref>

/ref>

The quinta was the site of Juan Perón's death on July 1, 1974. Perón, who had returned from exile following elections in 1973, took office with his politically neophyte wife, Isabel, as vice president; during her tenure as president, Juan and Evita Perón's caskets both lay in state at the mansion, (the

The quinta was the site of Juan Perón's death on July 1, 1974. Perón, who had returned from exile following elections in 1973, took office with his politically neophyte wife, Isabel, as vice president; during her tenure as president, Juan and Evita Perón's caskets both lay in state at the mansion, (the

The Quinta presidencial de Olivos, also known as Quinta de Olivos, is an architectural landmark in the north side

The Quinta presidencial de Olivos, also known as Quinta de Olivos, is an architectural landmark in the north side Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

suburb of Olivos and the official residence of the President of Argentina

The president of Argentina ( es, Presidente de Argentina), officially known as the president of the Argentine Nation ( es, Presidente de la Nación Argentina), is both head of state and head of government of Argentina. Under the national cons ...

.

It is one of the President's official residences.

Overview

Development

Shortly after the second foundation ofBuenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

by Captain Juan de Garay

Juan de Garay (1528–1583) was a Spanish conquistador.

Garay's birthplace is disputed. Some say it was in the city of Junta de Villalba de Losa in Castile, while others argue he was born in the area of Orduña (Basque Country). There's n ...

in 1580 (the first one was in 1536 by Pedro de Mendoza), among the first 400 land lots apportioned was that of a 180-hectare (450 acre) parcel 20 kilometers (13 mi) north of the city. The land, situated on a bluff overlooking the Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

, was awarded to Rodrigo de Ibarola, a lieutenant of Garay's. A prime section of the property was purchased in 1774 by Manuel de Basavilbaso, the Postmaster General of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata ( es, Virreinato del Río de la Plata or es, Virreinato de las Provincias del Río de la Plata) meaning "River of the Silver", also called " Viceroyalty of the River Plate" in some scholarly writings, i ...

. His daughter, Justa Rufina, married Miguel de Azcuénaga

Miguel de Azcuénaga (June 4, 1754 – December 19, 1833) was an Argentine brigadier. Educated in Spain, at the University of Seville, Azcuénaga began his military career in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata and became a member of the ...

, a military officer who would later take part in the May Revolution

The May Revolution ( es, Revolución de Mayo) was a week-long series of events that took place from May 18 to 25, 1810, in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. This Spanish colony included roughly the terri ...

of 1810 (prologue to the Argentine War of Independence

The Argentine War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de Argentina, links=no) was a secessionist civil war fought from 1810 to 1818 by Argentine patriotic forces under Manuel Belgrano, Juan José Castelli and José de San Martín ...

). He also established one of the area's first apiaries on the grounds.Taringa: Residencia Presidencial de Olivos /ref>

Buenos Aires Province

Buenos Aires (), officially the Buenos Aires Province (''Provincia de Buenos Aires'' ), is the largest and most populous Argentine province. It takes its name from the city of Buenos Aires, the capital of the country, which used to be part of th ...

Governor and strongman Juan Manuel de Rosas

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws", was an Argentine politician and army officer who ruled Buenos Aires Province and briefly the Argentine Confederation. Although ...

led to his exile in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

for a number of years. Azcuénaga ultimately returned and, in 1851, commissioned a graduate of the École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

, Prilidiano Pueyrredón, to design a manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals ...

. Pueyrredón created an eclectic design centered on Neogothic and Baroque architecture

Baroque architecture is a highly decorative and theatrical style which appeared in Italy in the early 17th century and gradually spread across Europe. It was originally introduced by the Catholic Church, particularly by the Jesuits, as a means ...

, and upon its completion in 1854, Azcuénaga came to refer to the mansion as his "birdcage"; Pueyrredón was also a renowned painter, and created a portrait of his friend and client shortly after the mansion's completion.

Azcuénaga landscaped the sprawling property with a selection of palm tree

The Arecaceae is a family of perennial flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are called palm tr ...

s, among them '' Butia'', ''Phoenix canariensis

''Phoenix canariensis'', the Canary Island date palm or pineapple palm, is a species of flowering plant in the palm family Arecaceae, native to the Canary Islands off the coast of Morocco. It is a relative of '' Phoenix dactylifera'', the tr ...

'', and ''Chamaerops humilis

''Chamaerops'' is a genus of flowering plants in the family Arecaceae. The only currently fully accepted species is ''Chamaerops humilis'', variously called European fan palm or the Mediterranean dwarf palm. It is one of the most cold-hardy ...

''. He also had vast extensions planted with ''Araucaria bidwillii

''Araucaria bidwillii'', commonly known as the bunya pine and sometimes referred to as the false monkey puzzle tree, is a large evergreen coniferous tree in the plant family Araucariaceae. It is found naturally in south-east Queensland Aust ...

'', cedars, cryptomeria

''Cryptomeria'' (literally "hidden parts") is a monotypic genus of conifer in the cypress family Cupressaceae, formerly belonging to the family Taxodiaceae. It includes only one species, ''Cryptomeria japonica'' ( syn. ''Cupressus japonica'' ...

s, cypress

Cypress is a common name for various coniferous trees or shrubs of northern temperate regions that belong to the family Cupressaceae. The word ''cypress'' is derived from Old French ''cipres'', which was imported from Latin ''cypressus'', the l ...

es, tipas and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

s planted, as well as a row of plantain

Plantain may refer to:

Plants and fruits

* Cooking banana, banana cultivars in the genus ''Musa'' whose fruits are generally used in cooking

** True plantains, a group of cultivars of the genus ''Musa''

* ''Plantaginaceae'', a family of flowerin ...

s (which graced his favorite path). Azcuénaga, who had no legitimate offspring, bequeathed the property to his nephew, Antonio Justo Olaguer Feliú. The blind Olaguer, who had no use for the view of the waterfront, sold the easternmost portion of the land before his death in 1903 and bequeathed it to his nephew, Carlos Villate Olaguer. Villate stipulated on his receiving the property that, upon his death, it should be deeded to the Argentine Government for the purpose of its use as the Official Summer Residence of the President of Argentina.''Revista del Notariado'': La Quinta de Olivos /ref>

Bequeathal to State

Villate's death in 1913 made the 35-hectare (86-acre) property available to the government, though its conversion into a public park was considered for a number of years (it had been customary for Argentine Presidents to reside in their own home). PresidentHipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

ultimately accepted the deed on September 30, 1918, though he designated it as the Residence of the Minister of Foreign Relations, rather than putting it to presidential use, and its first official occupant was Foreign Minister Honorio Pueyrredón. A coup in 1930 and the installation of General José Félix Uriburu gave the estate its first use as a presidential residence when the infirm dictator opted for the spot's breeze and tranquility during a 1931 heat wave.

Uriburu's successor, Agustín P. Justo, planned a vacation resort at the site in 1933. The Villate deed prevented him legally from doing so, though, and in 1936, he formally inaugurated the estate as the Residence of the President of Argentina, while ceding the western portion to the Military Officers' Association. President Justo also initiated beautification projects for the surrounding area, having an extensive row of jacaranda trees planted along the Avenida del Libertador; among his first guests at the residence, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, remarked during his drive at seeing the falling blooms that "it's raining blue!" ''La Nación'': Historias de la quinta presidencial /ref>

Presidential Residence

The estate's use as a year-round residence triggered a lawsuit in 1940 by Villate's heirs, alleging that it violated the terms of the will. The suit was struck down by theArgentine Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Argentina ( es, link=no, Corte Suprema de Argentina), officially known as the Supreme Court of Justice of the Argentine Nation ( es, link=no, Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación Argentina, CSJN), is the highest court of l ...

, however. Its relatively distant location from the downtown Buenos Aires presidential offices at the Casa Rosada

The ''Casa Rosada'' (, eng, Pink House) is the office of the president of Argentina. The palatial mansion is known officially as ''Casa de Gobierno'' ("House of Government" or "Government House"). Normally, the president lives at the Quinta de ...

made it of only occasional use in subsequent years. President Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected ...

installed a screening room, and had the grounds embellished with an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

, tennis court

A tennis court is the venue where the sport of tennis is played. It is a firm rectangular surface with a low net stretched across the centre. The same surface can be used to play both doubles and singles matches. A variety of surfaces can be ...

s, reflecting pool, greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic conditions are grown.These ...

, ''Ceiba speciosa

''Ceiba speciosa'', the floss silk tree (formerly ''Chorisia speciosa''), is a species of deciduous tree that is native to the tropical and subtropical forests of South America. It has several local common names, such as ''palo borracho'' (in S ...

'' trees, and other additions, though he later attracted controversy following the 1952 death of his wife, Evita, when he also converted former polo

Polo is a ball game played on horseback, a traditional field sport and one of the world's oldest known team sports. The game is played by two opposing teams with the objective of scoring using a long-handled wooden mallet to hit a small ha ...

horse stables on the grounds into installations for the "Union of Secondary School Students" (UES) - a group of athletic, adolescent girls - to which the widower provided discreet access via a tunnel built in 1953 (not unlike "Harding

Harding may refer to:

People

*Harding (surname)

*Maureen Harding Clark (born 1946), Irish jurist

Places Australia

* Harding River

Iran

* Harding, Iran, a village in South Khorasan Province

South Africa

* Harding, KwaZulu-Natal

United St ...

's Tunnel").Page, Joseph. ''Perón: A Biography''. Random House, 1983.

The scandal helped precipitate Perón's overthrow in 1955, and General Pedro Aramburu

Pedro Eugenio Aramburu Silveti (May 21, 1903 – June 1, 1970) was an Argentine Army general. He was a major figure behind the ''Revolución Libertadora'', the military coup against Juan Perón in 1955. He became dictator of Argentina, serving ...

became the first president to reside habitually at the Quinta de Olivos. The quinta became the site of secret negotiations in 1961, between President Arturo Frondizi

Arturo Frondizi Ércoli (October 28, 1908 – April 18, 1995) was an Argentine lawyer, journalist, teacher and politician, who was elected President of Argentina and ruled between May 1, 1958 and March 29, 1962, when he was overthrown by a ...

and the Argentine-born Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

n revolutionary and economy minister, Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

- an attempt by Frondizi to mediate the US-Cuba conflict that, once discovered, helped result in his own overthrow in 1962. The site of frequent asado

' () is the technique and the social event of having or attending a barbecue in various South American countries, especially Argentina, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay where it is also a traditional event. An ''asado'' usually consists of beef, por ...

s and other social gatherings, a concert organized by President Juan Carlos Onganía

Juan Carlos Onganía Carballo (; 17 March 1914 – 8 June 1995) was President of Argentina from 29 June 1966 to 8 June 1970. He rose to power as dictator after toppling the president Arturo Illia in a coup d'état self-named ''Revolución Argen ...

in 1969 led to a fire that caused the historic residence extensive damage, though it retained most of its original structure.

The quinta was the site of Juan Perón's death on July 1, 1974. Perón, who had returned from exile following elections in 1973, took office with his politically neophyte wife, Isabel, as vice president; during her tenure as president, Juan and Evita Perón's caskets both lay in state at the mansion, (the

The quinta was the site of Juan Perón's death on July 1, 1974. Perón, who had returned from exile following elections in 1973, took office with his politically neophyte wife, Isabel, as vice president; during her tenure as president, Juan and Evita Perón's caskets both lay in state at the mansion, (the March 1976 coup

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of March ...

resulted in their interment in Chacarita and Recoleta cemeteries, respectively). The compound's opulence prompted a number of Argentine presidents over the years to forego residing there, notably Dr. Héctor Cámpora

Hector () is an English, French, Scottish, and Spanish given name. The name is derived from the name of Hektor, a legendary Trojan champion who was killed by the Greek Achilles. The name ''Hektor'' is probably derived from the Greek ''ékhein'', ...

, General Leopoldo Galtieri

Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri (; 15 July 1926 12 January 2003) was an Argentine general and politician of Italian descent who served as President of Argentina from December 1981 to June 1982. Galtieri ruled as a military dictator during the Na ...

(who preferred officers' quarters at the Campo de Mayo

Campo de Mayo is a military base located in Greater Buenos Aires, Argentina, northwest of Buenos Aires.

Campo de Mayo covers an area of and is one of the most important military bases in Argentina, including Argentine Army's:

* General Lemos Co ...

Army Base), and Eduardo Duhalde

Eduardo Alberto Duhalde (; born 5 October 1941) is an Argentine Peronist politician who served as the interim President of Argentina from January 2002 to May 2003. He also served as Vice President and Governor of Buenos Aires in the 1990s.

Bo ...

(who took office during a historic crisis in 2002).

Later additions include a heliport

A heliport is a small airport suitable for use by helicopters and some other vertical lift aircraft. Designated heliports typically contain one or more touchdown and liftoff areas and may also have limited facilities such as fuel or hangars. I ...

(1969), a chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type ...

(1972), and a miniature golf

Miniature golf, also known as minigolf, mini-putt, crazy golf, or putt-putt, is an offshoot of the sport of golf focusing solely on the putting aspect of its parent game. The aim of the game is to score the lowest number of points. It is played ...

course installed by President Carlos Menem

Carlos Saúl Menem (2 July 1930 – 14 February 2021) was an Argentine lawyer and politician who served as the President of Argentina from 1989 to 1999. Ideologically, he identified as a Peronist and supported economically liberal policies. He ...

in 1991. The residence hosted the Olivos Pact

The Olivos Pact ( es, Pacto de Olivos) refers to a series of documents signed on November 17, 1993, between the governing President of Argentina, Carlos Menem, and former President and leader of the opposition UCR, Raúl Alfonsín, that formed th ...

, a political agreement signed on November 14, 1993, between Menem and former President Raúl Alfonsín (head of the main opposition party, the centrist Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union ( es, Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) is a centrist and social-liberal political party in Argentina. It has been ideologically heterogeneous, ranging from social liberalism to social democracy. The UCR is a member of the S ...

). The pact secured support for the 1994 reform of the Argentine Constitution

The 1994 amendment to the Constitution of Argentina was approved on 22 August 1994 by a Constitutional Assembly that met in the twin cities of Santa Fe and Paraná. The calling for elections for the Constitutional Convention and the main issues t ...

, which provided for the president's right to seek re-election, as well as for the popular election of the mayor of Buenos Aires, hitherto a presidentially-appointed post.

References

{{Presidential palaces in South America Official residences in Argentina Houses completed in 1854 Spanish Colonial architecture in Argentina Gothic Revival architecture in Argentina Presidential residences