Pump-jet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

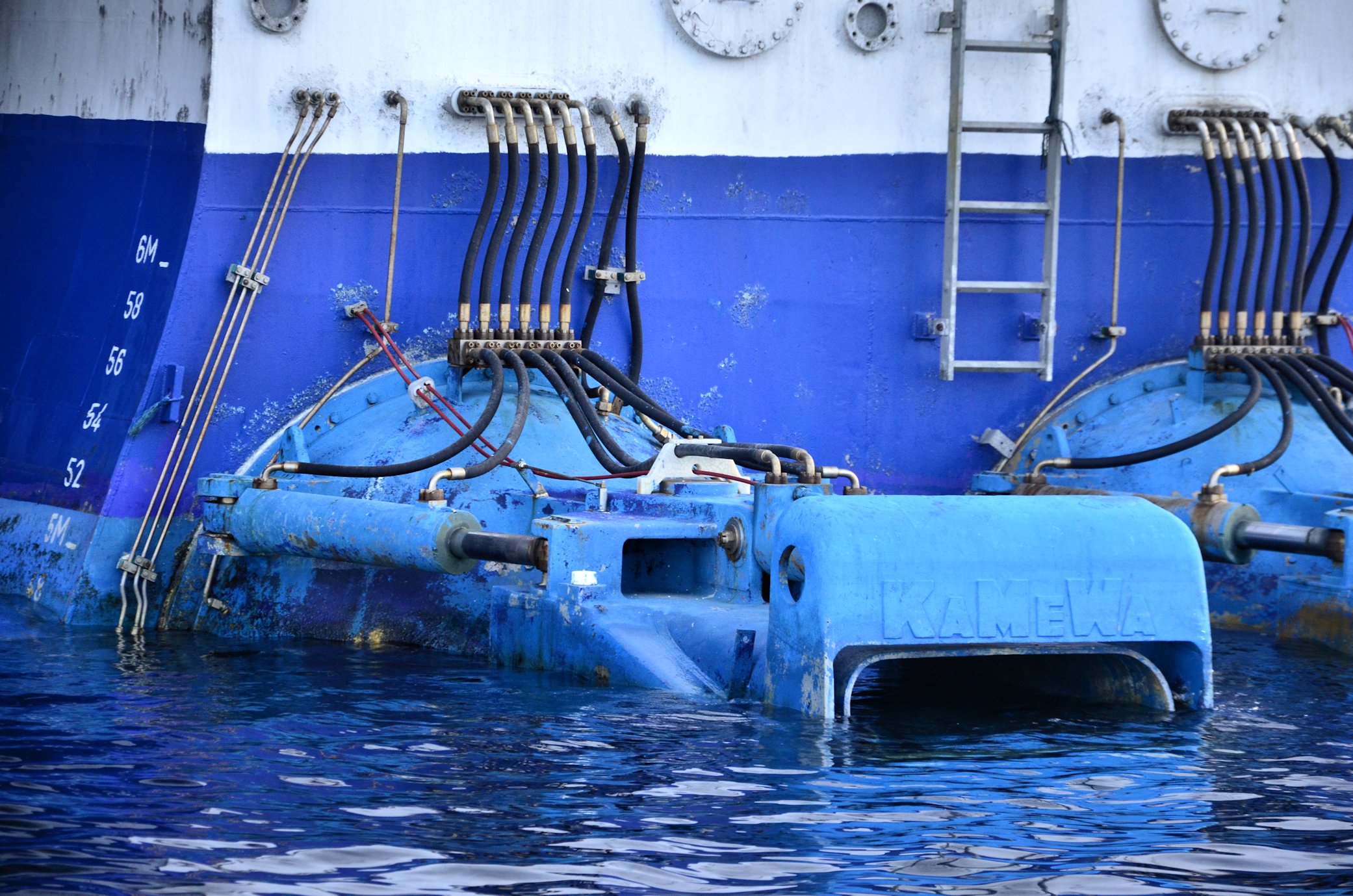

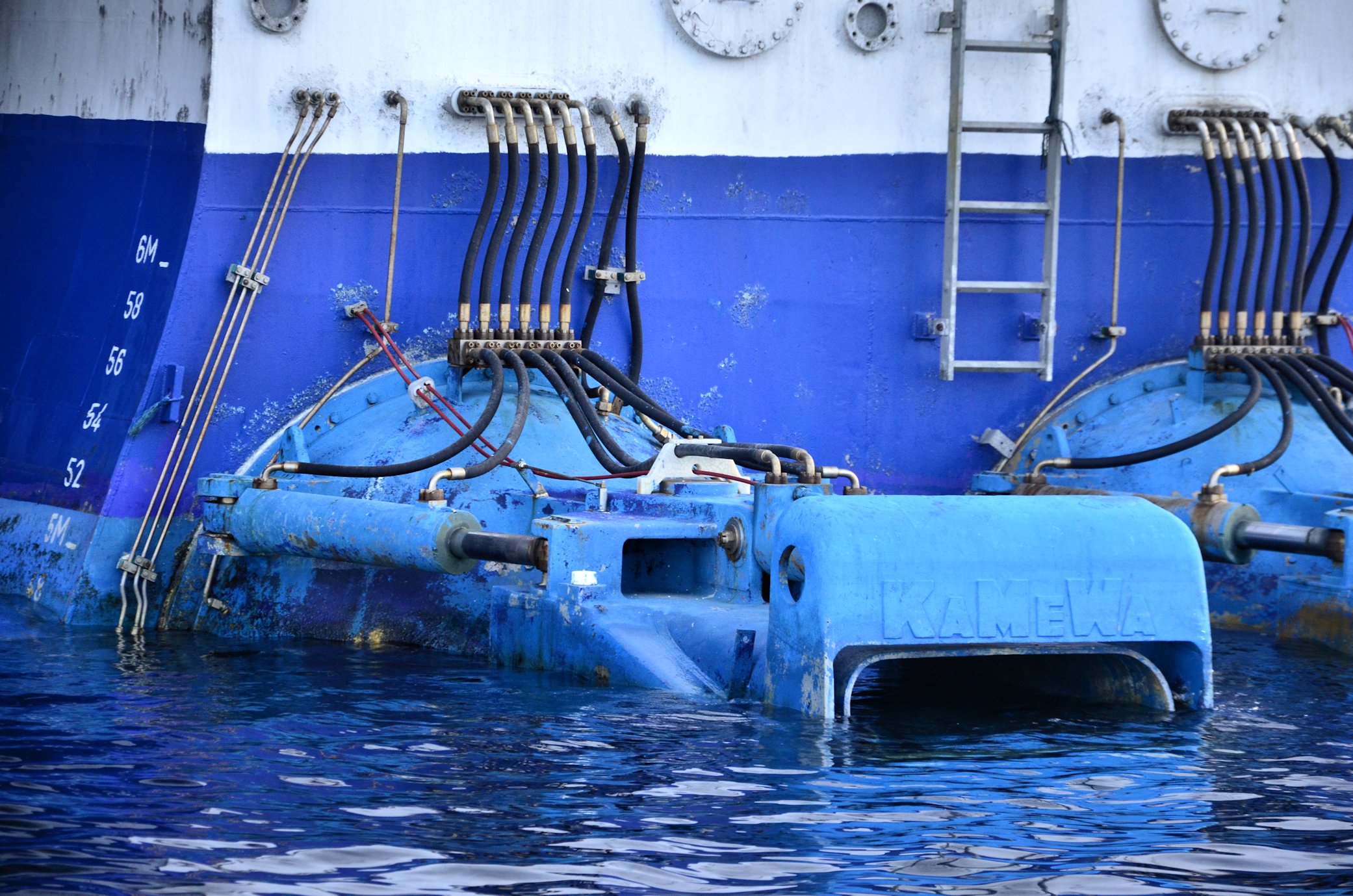

A pump-jet, hydrojet, or water jet is a

A pump-jet, hydrojet, or water jet is a

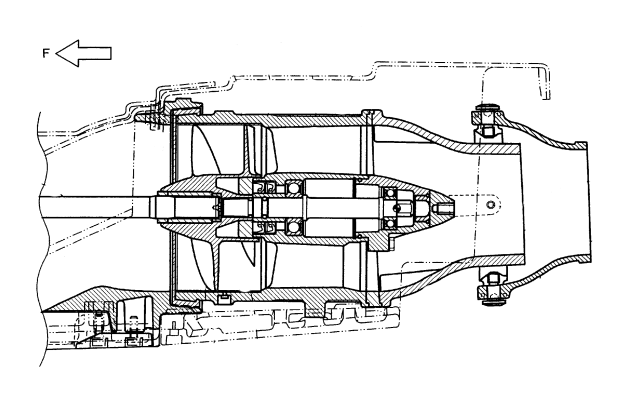

A pump-jet works by having an intake (usually at the bottom of the

A pump-jet works by having an intake (usually at the bottom of the

Pump-jet powered ships are very maneuverable. Examples of ships using pumpjets are the s, the s, s, the Stena

marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

system that produces a jet of water for propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived f ...

. The mechanical arrangement may be a ducted propeller ( axial-flow pump), a centrifugal pump

Centrifugal pumps are used to transport fluids by the conversion of rotational kinetic energy to the hydrodynamic energy of the fluid flow. The rotational energy typically comes from an engine or electric motor. They are a sub-class of dynamic ...

, or a mixed flow pump which is a combination of both centrifugal and axial designs. The design also incorporates an intake to provide water to the pump and a nozzle to direct the flow of water out of the pump.http://www.hamiltonmarine.co.nz/includes/files_cms/file/JetTorque%2008.pdf

Design

hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

) that allows water to pass underneath the vessel into the engines. Water enters the pump

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic energy. Pumps can be classified into three major groups according to the method they ...

through this inlet. The pump can be of a centrifugal

Centrifugal (a key concept in rotating systems) may refer to:

*Centrifugal casting (industrial), Centrifugal casting (silversmithing), and Spin casting (centrifugal rubber mold casting), forms of centrifigual casting

*Centrifugal clutch

*Centrifu ...

design for high speeds, or an axial flow pump for low to medium speeds. The water pressure inside the inlet is increased by the pump and forced backwards through a nozzle. With the use of a ''reversing bucket'', reverse thrust can also be achieved for faring backwards, quickly and without the need to change gear

A gear is a rotating circular machine part having cut teeth or, in the case of a cogwheel or gearwheel, inserted teeth (called ''cogs''), which mesh with another (compatible) toothed part to transmit (convert) torque and speed. The basic ...

or adjust engine thrust. The reversing bucket can also be used to help slow the ship down when braking. This feature is the main reason pump jets are so maneuverable.

The nozzle also provides the steering of the pump-jets. Plates, similar to rudders, can be attached to the nozzle in order to redirect the water flow port and starboard. In a way, this is similar to the principles of air ''thrust vectoring

Thrust vectoring, also known as thrust vector control (TVC), is the ability of an aircraft, rocket, or other vehicle to manipulate the direction of the thrust from its engine(s) or motor(s) to control the attitude or angular velocity of the ve ...

'', a technique which has long been used in launch vehicles (rockets and missiles) then later in military jet-powered aircraft. This provides pumpjet-powered ships with superior agility at sea. Another advantage is that when faring backwards by using the reversing bucket, steering is not inverted, as opposed to propeller-powered ships.

Axial flow

An axial-flow waterjet's pressure is increased by diffusing the flow as it passes through the impeller blades and stator vanes. The pump nozzle then converts this pressure energy into velocity, thus producing thrust. Axial-flow waterjets produce high volumes at lower velocity, making them well suited to larger low to medium speed craft, the exception beingpersonal water craft

A personal watercraft (PWC), also called water scooter or jet ski, is a recreational watercraft that a rider sits or stands on, not within, as in a boat. PWCs have two style categories, first and most popular being a runabout or "sit down" whe ...

, where the high water volumes create tremendous thrust and acceleration as well as high top speeds. But these craft also have high power-to-weight ratios compared to most marine craft. Axial-flow waterjets are by far the most common type of pump.

Mixed flow

Mixed-flow waterjet designs incorporate aspects of both axial flow and centrifugal flow pumps. Pressure is developed by both diffusion and radial outflow. Mixed flow designs produce lower volumes of water at high velocity making them suited for small to moderate craft sizes and higher speeds. Common uses include high speed pleasure craft and waterjets for shallow water river racing (see River Marathon).Centrifugal flow

Centrifugal-flow waterjet designs make use of radial flow to create water pressure. Centrifugal designs are no longer commonly used except on outboard sterndrives.Advantages

Pump jets have some advantages over bare propellers for certain applications, usually related to requirements for high-speed or shallow- draft operations. These include: * Higher speed before the onset ofcavitation

Cavitation is a phenomenon in which the static pressure of a liquid reduces to below the liquid's vapour pressure, leading to the formation of small vapor-filled cavities in the liquid. When subjected to higher pressure, these cavities, ca ...

, because of the raised internal dynamic pressure

In fluid dynamics, dynamic pressure (denoted by or and sometimes called velocity pressure) is the quantity defined by:Clancy, L.J., ''Aerodynamics'', Section 3.5

:q = \frac\rho\, u^2

where (in SI units):

* is the dynamic pressure in pascals ( ...

* High power density (with respect to volume) of both the propulsor and the prime mover (because a smaller, higher-speed unit can be used)

* Protection of the rotating element, making operation safer around swimmers and aquatic life

* Improved shallow-water operations, because only the inlet needs to be submerged

* Increased maneuverability, by adding a steerable nozzle to create vectored thrust

Thrust vectoring, also known as thrust vector control (TVC), is the ability of an aircraft, rocket, or other vehicle to manipulate the direction of the thrust from its engine(s) or motor(s) to control the attitude or angular velocity of the v ...

* Noise reduction, resulting in a low sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on o ...

signature; this particular system has little in common with other pump-jet propulsors and is also known as "shrouded propeller configuration"; applications:

** Warships

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster an ...

designed for low observability, for example the Swedish.

** Submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, for example the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

and , the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

and , the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

and ''Barracuda'' class, and the Russian Navy .

** Modern torpedoes, such as the Spearfish

Spearfish may refer to:

Places

*Spearfish, South Dakota, United States

* North Spearfish, South Dakota, United States

* Spearfish Formation, a geologic formation in the United States

Biology

* ''Tetrapturus'', a genus of marlin containing spe ...

, the Mk 48 and Mk 50 weapons.

History

The water jet principle in shipping industry can be traced back to 1661 when Toogood and Hayes produced a description of a ship having a central water channel in which either a plunger or centrifugal pump was installed to provide the motive power. On December 3, 1787, inventor James Rumsey demonstrated a water-jet propelled boat using a steam-powered pump to drive a stream of water from the stern. This occurred on the Potomac River at Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia) before a crowd of witnesses including General Horatio Gates. The 50-foot long boat traveled about one-half mile upriver before returning to the dock. The boat was reported to reach a speed of four mph moving upstream. In April 1932, Italian engineer Secondo Campini demonstrated a pump-jet propelled boat inVenice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The boat achieved a top speed of , a speed comparable to a boat with a conventional engine of similar output. The Italian Navy, who had funded the development of the boat, placed no orders but did veto the sale of the design outside of Italy. The first modern jetboat

A jetboat is a boat propelled by a jet of water ejected from the back of the craft. Unlike a powerboat or motorboat that uses an external propeller in the water below or behind the boat, a jetboat draws the water from under the boat through ...

was developed by New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

engineer Sir William Hamilton in the mid 1950s.

Uses

Pump-jets were once limited to high-speed pleasure craft (such as jet skis andjetboat

A jetboat is a boat propelled by a jet of water ejected from the back of the craft. Unlike a powerboat or motorboat that uses an external propeller in the water below or behind the boat, a jetboat draws the water from under the boat through ...

s) and other small vessels, but since 2000 the desire for high-speed vessels has increased and thus the pump-jet is gaining popularity on larger craft, military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

vessels and ferries. On these larger craft, they can be powered by diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-cal ...

s or gas turbine

A gas turbine, also called a combustion turbine, is a type of continuous flow internal combustion engine. The main parts common to all gas turbine engines form the power-producing part (known as the gas generator or core) and are, in the directio ...

s. Speeds of up to can be achieved with this configuration, even with a displacement hull.The Information page of the Stena HSS 1500Pump-jet powered ships are very maneuverable. Examples of ships using pumpjets are the s, the s, s, the Stena

high-speed sea service

High-speed Sea Service or Stena HSS was a class of high-speed craft developed by and originally operated by Stena Line on European international ferry routes. The HSS 1500 had an in-service speed of 40 knots (75 km/h).

Several paten ...

ferries, the United States ''Seawolf''-class and ''Virginia''-class, as well as the Russian ''Borei''-class submarines and the United States littoral combat ship

The littoral combat ship (LCS) is either of two classes of relatively small surface vessels designed for operations near shore by the United States Navy. It was "envisioned to be a networked, agile, stealthy surface combatant capable of defeat ...

s.

See also

* Internal drive propulsion *Personal water craft

A personal watercraft (PWC), also called water scooter or jet ski, is a recreational watercraft that a rider sits or stands on, not within, as in a boat. PWCs have two style categories, first and most popular being a runabout or "sit down" whe ...

* Wetbike

* Kitchen rudder

The Kitchen rudder is the familiar name for "Kitchen's Patent Reversing Rudders", a combination rudder and directional propulsion delivery system for relatively slow speed displacement boats which was invented in the early 20th century by John ...

* Water rocket

A water rocket is a type of model rocket using water as its reaction mass. The water is forced out by a pressurized gas, typically compressed air. Like all rocket engines, it operates on the principle of Newton's third law of motion. Water rock ...

* Chain boat - Water turbines

Notes

References

* Charles Dawson, "The Early History of the Water-jet Engine", "Industrial Heritage", Vol. 30, No 3, 2004, page 36. * David S. Yetman, "Without A Prop", DogEar Publishers, 2010 {{refend Marine propulsion Jet engines