Pterodactyl on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct

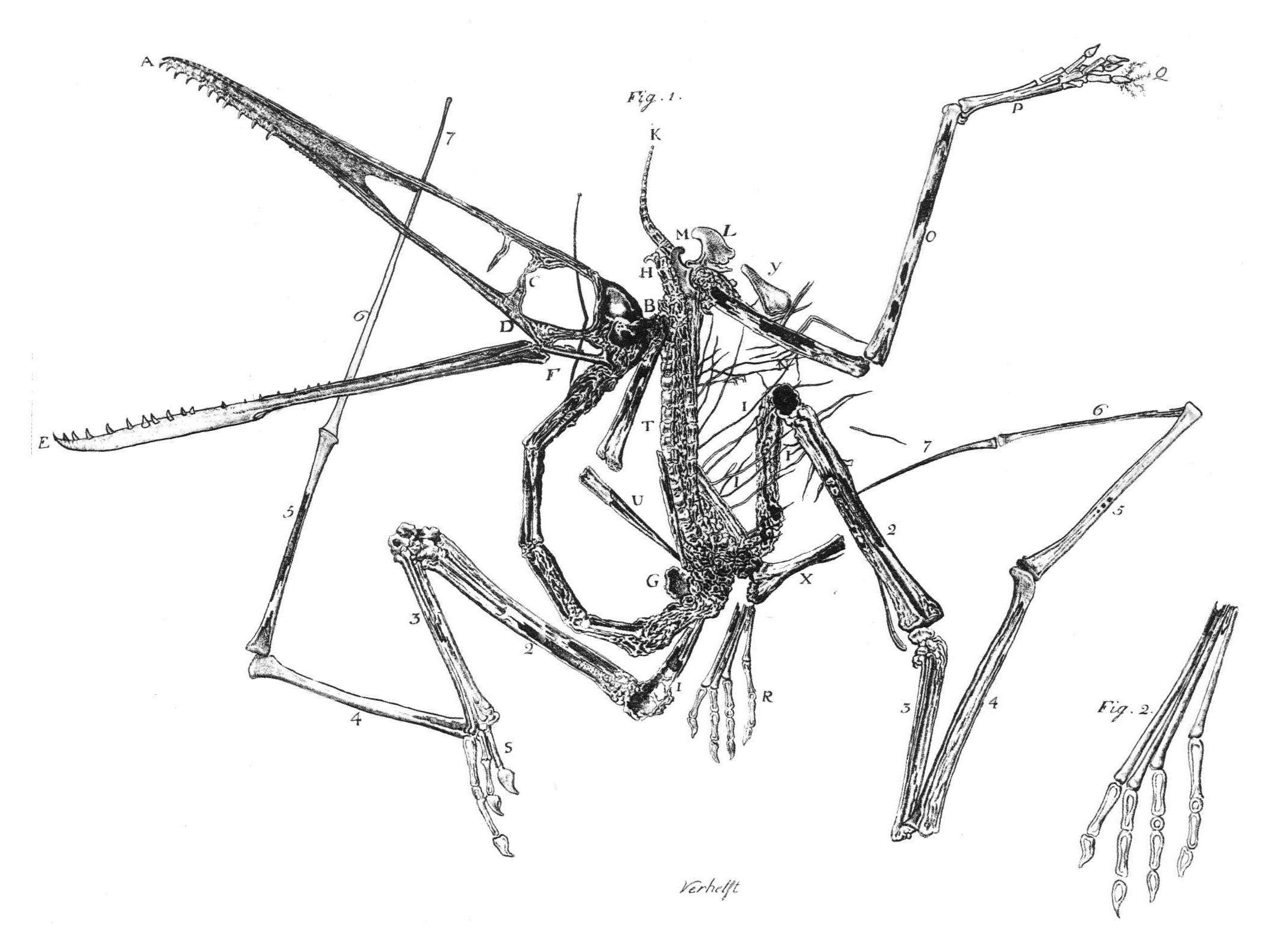

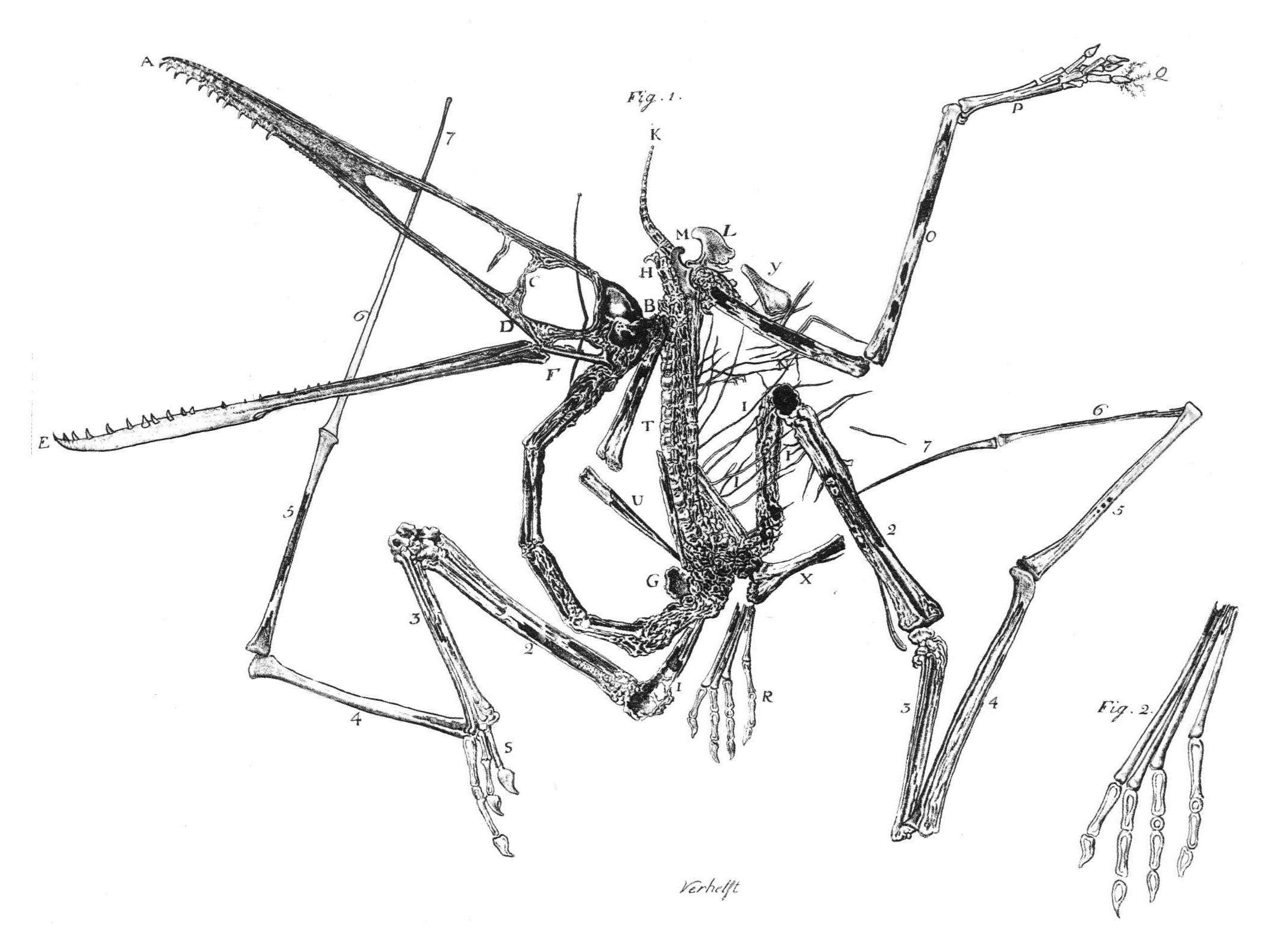

Compared to the other vertebrate flying groups, the birds and bats, pterosaur skulls were typically quite large. Most pterosaur skulls had elongated jaws. Their skull bones tend to be fused in adult individuals. Early pterosaurs often had

Compared to the other vertebrate flying groups, the birds and bats, pterosaur skulls were typically quite large. Most pterosaur skulls had elongated jaws. Their skull bones tend to be fused in adult individuals. Early pterosaurs often had  In some cases, fossilized

In some cases, fossilized  The public image of pterosaurs is defined by their elaborate head crests. This was influenced by the distinctive backward-pointing crest of the well-known ''

The public image of pterosaurs is defined by their elaborate head crests. This was influenced by the distinctive backward-pointing crest of the well-known ''

The

The  The neck of pterosaurs was relatively long and straight. In pterodactyloids, the neck is typically longer than the torso. This length is not caused by an increase of the number of vertebrae, which is invariably seven. Some researchers include two transitional "cervicodorsals" which brings the number to nine. Instead, the vertebrae themselves became more elongated, up to eight times longer than wide. Nevertheless, the cervicals were wider than high, implying a better vertical than horizontal neck mobility. Pterodactyloids have lost all neck ribs. Pterosaur necks were probably rather thick and well-muscled, especially vertically.

The torso was relatively short and egg-shaped. The vertebrae in the back of pterosaurs originally might have numbered eighteen. With advanced species a growing number of these tended to be incorporated into the

The neck of pterosaurs was relatively long and straight. In pterodactyloids, the neck is typically longer than the torso. This length is not caused by an increase of the number of vertebrae, which is invariably seven. Some researchers include two transitional "cervicodorsals" which brings the number to nine. Instead, the vertebrae themselves became more elongated, up to eight times longer than wide. Nevertheless, the cervicals were wider than high, implying a better vertical than horizontal neck mobility. Pterodactyloids have lost all neck ribs. Pterosaur necks were probably rather thick and well-muscled, especially vertically.

The torso was relatively short and egg-shaped. The vertebrae in the back of pterosaurs originally might have numbered eighteen. With advanced species a growing number of these tended to be incorporated into the  The tails of pterosaurs were always rather slender. This means that the caudofemoralis retractor muscle which in most basal Archosauria provides the main propulsive force for the hindlimb, was relatively unimportant. The tail vertebrae were amphicoelous, the vertebral bodies on both ends being concave. Early species had long tails, containing up to fifty caudal vertebrae, the middle ones stiffened by elongated articulation processes, the zygapophyses, and

The tails of pterosaurs were always rather slender. This means that the caudofemoralis retractor muscle which in most basal Archosauria provides the main propulsive force for the hindlimb, was relatively unimportant. The tail vertebrae were amphicoelous, the vertebral bodies on both ends being concave. Early species had long tails, containing up to fifty caudal vertebrae, the middle ones stiffened by elongated articulation processes, the zygapophyses, and

The

The

Pterosaur wings were formed by bones and membranes of skin and other tissues. The primary membranes attached to the extremely long fourth

Pterosaur wings were formed by bones and membranes of skin and other tissues. The primary membranes attached to the extremely long fourth  While historically thought of as simple leathery structures composed of skin, research has since shown that the wing membranes of pterosaurs were highly complex dynamic structures suited to an active style of flight. The outer wings (from the tip to the elbow) were strengthened by closely spaced fibers called ''

While historically thought of as simple leathery structures composed of skin, research has since shown that the wing membranes of pterosaurs were highly complex dynamic structures suited to an active style of flight. The outer wings (from the tip to the elbow) were strengthened by closely spaced fibers called ''

The pterosaur wing membrane is divided into three basic units. The first, called the ''propatagium'' ("fore membrane"), was the forward-most part of the wing and attached between the wrist and shoulder, creating the "leading edge" during flight. The ''patagium, brachiopatagium'' ("arm membrane") was the primary component of the wing, stretching from the highly elongated fourth finger of the hand to the hindlimbs. Finally, at least some pterosaur groups had a membrane that stretched between the legs, possibly connecting to or incorporating the tail, called the uropatagium; the extent of this membrane is not certain, as studies on ''Sordes'' seem to suggest that it simply connected the legs but did not involve the tail (rendering it a cruropatagium). A common interpretation is that Rhamphorhynchoidea, non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs had a broader uro/cruropatagium stretched between their long fifth toes, with pterodactyloids, lacking such toes, only having membranes running along the legs.

There has been considerable argument among paleontologists about whether the main wing membranes (brachiopatagia) attached to the hindlimbs, and if so, where. Fossils of the rhamphorhynchoid ''Sordes'', the anurognathid ''

The pterosaur wing membrane is divided into three basic units. The first, called the ''propatagium'' ("fore membrane"), was the forward-most part of the wing and attached between the wrist and shoulder, creating the "leading edge" during flight. The ''patagium, brachiopatagium'' ("arm membrane") was the primary component of the wing, stretching from the highly elongated fourth finger of the hand to the hindlimbs. Finally, at least some pterosaur groups had a membrane that stretched between the legs, possibly connecting to or incorporating the tail, called the uropatagium; the extent of this membrane is not certain, as studies on ''Sordes'' seem to suggest that it simply connected the legs but did not involve the tail (rendering it a cruropatagium). A common interpretation is that Rhamphorhynchoidea, non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs had a broader uro/cruropatagium stretched between their long fifth toes, with pterodactyloids, lacking such toes, only having membranes running along the legs.

There has been considerable argument among paleontologists about whether the main wing membranes (brachiopatagia) attached to the hindlimbs, and if so, where. Fossils of the rhamphorhynchoid ''Sordes'', the anurognathid ''

The pelvis of pterosaurs was of moderate size compared to the body as a whole. Often the three pelvic bones were fused. The Ilium (bone), ilium was long and low, its front and rear blades projecting horizontally beyond the edges of the lower pelvic bones. Despite this length, the rod-like form of these processes indicates that the hindlimb muscles attached to them were limited in strength. The, in side view narrow, pubic bone fused with the broad ischium into an ischiopubic blade. Sometimes, the blades of both sides were also fused, closing the pelvis from below and forming the pelvic canal. The hip joint was not perforated and allowed considerable mobility to the leg. It was directed obliquely upwards, preventing a perfectly vertical position of the leg.

The front of the pubic bones articulated with a unique structure, the paired prepubic bones. Together these formed a cusp covering the rear belly, between the pelvis and the belly ribs. The vertical mobility of this element suggests a function in breathing, compensating the relative rigidity of the chest cavity.

The pelvis of pterosaurs was of moderate size compared to the body as a whole. Often the three pelvic bones were fused. The Ilium (bone), ilium was long and low, its front and rear blades projecting horizontally beyond the edges of the lower pelvic bones. Despite this length, the rod-like form of these processes indicates that the hindlimb muscles attached to them were limited in strength. The, in side view narrow, pubic bone fused with the broad ischium into an ischiopubic blade. Sometimes, the blades of both sides were also fused, closing the pelvis from below and forming the pelvic canal. The hip joint was not perforated and allowed considerable mobility to the leg. It was directed obliquely upwards, preventing a perfectly vertical position of the leg.

The front of the pubic bones articulated with a unique structure, the paired prepubic bones. Together these formed a cusp covering the rear belly, between the pelvis and the belly ribs. The vertical mobility of this element suggests a function in breathing, compensating the relative rigidity of the chest cavity.

Most or all pterosaurs had hair-like filaments known as pycnofibers on the head and torso. The term "pycnofiber", meaning "dense filament", was coined by palaeontologist Alexander Kellner and colleagues in 2009. Pycnofibers were unique structures similar to, but not homology (biology), homologous (sharing a common origin) with, mammalian hair, an example of convergent evolution. A fuzzy integument was first reported from a specimen of ''Scaphognathus crassirostris'' in 1831 by Georg August Goldfuss, but had been widely doubted. Since the 1990s, pterosaur finds and histology, histological and ultraviolet examination of pterosaur specimens have provided incontrovertible proof: pterosaurs had pycnofiber coats. ''Sordes, Sordes pilosus'' (which translates as "hairy demon") and ''Jeholopterus, Jeholopterus ninchengensis'' show pycnofibers on the head and body.

Most or all pterosaurs had hair-like filaments known as pycnofibers on the head and torso. The term "pycnofiber", meaning "dense filament", was coined by palaeontologist Alexander Kellner and colleagues in 2009. Pycnofibers were unique structures similar to, but not homology (biology), homologous (sharing a common origin) with, mammalian hair, an example of convergent evolution. A fuzzy integument was first reported from a specimen of ''Scaphognathus crassirostris'' in 1831 by Georg August Goldfuss, but had been widely doubted. Since the 1990s, pterosaur finds and histology, histological and ultraviolet examination of pterosaur specimens have provided incontrovertible proof: pterosaurs had pycnofiber coats. ''Sordes, Sordes pilosus'' (which translates as "hairy demon") and ''Jeholopterus, Jeholopterus ninchengensis'' show pycnofibers on the head and body.

The presence of pycnofibers strongly indicates that pterosaurs were endothermic (warm-blooded). They aided thermoregulation, as is common in warm-blooded animals who need insulation to prevent excessive heat-loss. Pycnofibers were flexible, short filaments, about five to seven millimetres long and rather simple in structure with a hollow central canal. Pterosaur pelts might have been comparable in density to many Mesozoic mammals.

The presence of pycnofibers strongly indicates that pterosaurs were endothermic (warm-blooded). They aided thermoregulation, as is common in warm-blooded animals who need insulation to prevent excessive heat-loss. Pycnofibers were flexible, short filaments, about five to seven millimetres long and rather simple in structure with a hollow central canal. Pterosaur pelts might have been comparable in density to many Mesozoic mammals.

Pterosaur fossils are very rare, due to their light bone construction. Complete skeletons can generally only be found in geological layers with exceptional preservation conditions, the so-called ''Lagerstätten''. The pieces from one such ''Lagerstätte'', the Late Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone in Bavaria, became much sought after by rich collectors. In 1784, the Italian naturalist Cosimo Alessandro Collini was the first scientist in history to describe a pterosaur fossil. At that time the concepts of evolution and extinction were only imperfectly developed. The bizarre build of the pterosaur was therefore shocking, as it could not clearly be assigned to any existing animal group. The discovery of pterosaurs would thus play an important role in the progress of modern paleontology and geology. Scientific opinion at the time was that if such creatures were still alive, only the sea was a credible habitat; Collini suggested it might be a swimming animal that used its long front limbs as paddles.Collini, C.A. (1784). "Sur quelques Zoolithes du Cabinet d'Histoire naturelle de S. A. S. E. Palatine & de Bavière, à Mannheim." ''Acta Theodoro-Palatinae Mannheim 5 Pars Physica'', pp. 58–103 (1 plate). A few scientists continued to support the aquatic interpretation even until 1830, when the German zoologist Johann Georg Wagler suggested that ''Pterodactylus'' used its wings as flippers and was affiliated with Ichthyosauria and Plesiosauria.Wagler, J. (1830). ''Natürliches System der Amphibien'' Munich, 1830: 1–354.

Pterosaur fossils are very rare, due to their light bone construction. Complete skeletons can generally only be found in geological layers with exceptional preservation conditions, the so-called ''Lagerstätten''. The pieces from one such ''Lagerstätte'', the Late Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone in Bavaria, became much sought after by rich collectors. In 1784, the Italian naturalist Cosimo Alessandro Collini was the first scientist in history to describe a pterosaur fossil. At that time the concepts of evolution and extinction were only imperfectly developed. The bizarre build of the pterosaur was therefore shocking, as it could not clearly be assigned to any existing animal group. The discovery of pterosaurs would thus play an important role in the progress of modern paleontology and geology. Scientific opinion at the time was that if such creatures were still alive, only the sea was a credible habitat; Collini suggested it might be a swimming animal that used its long front limbs as paddles.Collini, C.A. (1784). "Sur quelques Zoolithes du Cabinet d'Histoire naturelle de S. A. S. E. Palatine & de Bavière, à Mannheim." ''Acta Theodoro-Palatinae Mannheim 5 Pars Physica'', pp. 58–103 (1 plate). A few scientists continued to support the aquatic interpretation even until 1830, when the German zoologist Johann Georg Wagler suggested that ''Pterodactylus'' used its wings as flippers and was affiliated with Ichthyosauria and Plesiosauria.Wagler, J. (1830). ''Natürliches System der Amphibien'' Munich, 1830: 1–354.

In 1800, Johann Hermann first suggested that it represented a flying creature in a letter to Georges Cuvier. Cuvier agreed in 1801, understanding it was an extinct flying reptile. In 1809, he coined the name ''Ptéro-Dactyle'', "wing-finger". This was in 1815 Latinised to ''

In 1800, Johann Hermann first suggested that it represented a flying creature in a letter to Georges Cuvier. Cuvier agreed in 1801, understanding it was an extinct flying reptile. In 1809, he coined the name ''Ptéro-Dactyle'', "wing-finger". This was in 1815 Latinised to ''

In 1828, Mary Anning found in England the first pterosaur genus outside Germany, named as ''

In 1828, Mary Anning found in England the first pterosaur genus outside Germany, named as ''

The situation for dinosaurs was comparable. From the 1960s onwards, a dinosaur renaissance took place, a quick increase in the number of studies and critical ideas, influenced by the discovery of additional fossils of ''Deinonychus'', whose spectacular traits refuted what had become entrenched orthodoxy. In 1970, likewise the description of the furry pterosaur ''Sordes'' began what Robert Bakker named a renaissance of pterosaurs. Kevin Padian especially propagated the new views, publishing a series of studies depicting pterosaurs as warm-blooded, active and running animals. This coincided with a revival of the German school through the work of Peter Wellnhofer, who in 1970s laid the foundations of modern pterosaur science. In 1978, he published the first pterosaur textbook, the ''Handbuch der Paläoherptologie, Teil 19: Pterosauria'', and in 1991 the second ever popular science pterosaur book, the ''Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs''.

The situation for dinosaurs was comparable. From the 1960s onwards, a dinosaur renaissance took place, a quick increase in the number of studies and critical ideas, influenced by the discovery of additional fossils of ''Deinonychus'', whose spectacular traits refuted what had become entrenched orthodoxy. In 1970, likewise the description of the furry pterosaur ''Sordes'' began what Robert Bakker named a renaissance of pterosaurs. Kevin Padian especially propagated the new views, publishing a series of studies depicting pterosaurs as warm-blooded, active and running animals. This coincided with a revival of the German school through the work of Peter Wellnhofer, who in 1970s laid the foundations of modern pterosaur science. In 1978, he published the first pterosaur textbook, the ''Handbuch der Paläoherptologie, Teil 19: Pterosauria'', and in 1991 the second ever popular science pterosaur book, the ''Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs''.

This development accelerated through the exploitation of two new ''Lagerstätten''. During the 1970s, the Early Cretaceous Santana Formation in Brazil began to produce chalk nodules that, though often limited in size and the completeness of the fossils they contained, perfectly preserved three-dimensional pterosaur skeletal parts. German and Dutch institutes bought such nodules from fossil poachers and prepared them in Europe, allowing their scientists to describe many new species and revealing a whole new fauna. Soon, Brazilian researchers, among them Alexander Kellner, intercepted the trade and named even more species.

Even more productive was the Early Cretaceous Chinese Jehol Biota of Liaoning that since the 1990s has brought forth hundreds of exquisitely preserved two-dimensional fossils, often showing soft tissue remains. Chinese researchers such as Lü Junchang have again named many new taxa. As discoveries also increased in other parts of the world, a sudden surge in the total of named genera took place. By 2009, when they had increased to about ninety, this growth showed no sign of levelling-off. In 2013, M.P. Witton indicated that the number of discovered pterosaur species had risen to 130. Over ninety percent of known taxa has been named during the "renaissance". Many of these were from groups the existence of which had been unknown. Advances in computing power allowed to determine their complex relationships through the quantitative method of cladistics. New and old fossils yielded much more information when subjected to modern ultraviolet light or roentgen photography, or CAT-scans. Insights from other fields of biology were applied to the data obtained. All this resulted in a substantial progress in pterosaur research, rendering older accounts in popular science books completely outdated.

In 2017 a fossil from a 170-million-year-old pterosaur, later named as the species ''Dearc sgiathanach'' in 2022, was discovered on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. The National Museum of Scotland claims that it the largest of its kind ever discovered from the Jurassic period, and it has been described as the world’s best-preserved skeleton of a pterosaur.

This development accelerated through the exploitation of two new ''Lagerstätten''. During the 1970s, the Early Cretaceous Santana Formation in Brazil began to produce chalk nodules that, though often limited in size and the completeness of the fossils they contained, perfectly preserved three-dimensional pterosaur skeletal parts. German and Dutch institutes bought such nodules from fossil poachers and prepared them in Europe, allowing their scientists to describe many new species and revealing a whole new fauna. Soon, Brazilian researchers, among them Alexander Kellner, intercepted the trade and named even more species.

Even more productive was the Early Cretaceous Chinese Jehol Biota of Liaoning that since the 1990s has brought forth hundreds of exquisitely preserved two-dimensional fossils, often showing soft tissue remains. Chinese researchers such as Lü Junchang have again named many new taxa. As discoveries also increased in other parts of the world, a sudden surge in the total of named genera took place. By 2009, when they had increased to about ninety, this growth showed no sign of levelling-off. In 2013, M.P. Witton indicated that the number of discovered pterosaur species had risen to 130. Over ninety percent of known taxa has been named during the "renaissance". Many of these were from groups the existence of which had been unknown. Advances in computing power allowed to determine their complex relationships through the quantitative method of cladistics. New and old fossils yielded much more information when subjected to modern ultraviolet light or roentgen photography, or CAT-scans. Insights from other fields of biology were applied to the data obtained. All this resulted in a substantial progress in pterosaur research, rendering older accounts in popular science books completely outdated.

In 2017 a fossil from a 170-million-year-old pterosaur, later named as the species ''Dearc sgiathanach'' in 2022, was discovered on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. The National Museum of Scotland claims that it the largest of its kind ever discovered from the Jurassic period, and it has been described as the world’s best-preserved skeleton of a pterosaur.

Because pterosaur anatomy has been so heavily modified for flight, and immediate transitional fossil predecessors have not so far been described, the ancestry of pterosaurs is not fully understood. The oldest known pterosaurs were already fully adapted to a flying lifestyle. Since Seeley, it was recognised that pterosaurs were likely to have had their origin in the "archosaurs", what today would be called the Archosauromorpha. In the 1980s, early cladistic analyses found that they were Avemetatarsalians (archosaurs closer to dinosaurs than to crocodilians). As this would make them also rather close relatives of the dinosaurs, these results were seen by Kevin Padian as confirming his interpretation of pterosaurs as bipedal warm-blooded animals. Because these early analyses were based on a limited number of taxa and characters, their results were inherently uncertain. Several influential researchers who rejected Padian's conclusions offered alternative hypotheses. David Unwin proposed an ancestry among the basal Archosauromorpha, specifically long-necked forms ("Protorosauria, protorosaurs") such as tanystropheids. A placement among archosauriformes, basal archosauriforms like ''Euparkeria'' was also suggested. Some basal archosauromorphs seem at first glance to be good candidates for close pterosaur relatives due to their long-limbed anatomy; one example is ''Sharovipteryx'', a "protorosaur" with skin membranes on its hindlimbs likely used for gliding. A 1999 study by Michael Benton found that pterosaurs were avemetatarsalians closely related to ''Scleromochlus,'' and named the group Ornithodira to encompass pterosaurs and dinosaurs''.''

Because pterosaur anatomy has been so heavily modified for flight, and immediate transitional fossil predecessors have not so far been described, the ancestry of pterosaurs is not fully understood. The oldest known pterosaurs were already fully adapted to a flying lifestyle. Since Seeley, it was recognised that pterosaurs were likely to have had their origin in the "archosaurs", what today would be called the Archosauromorpha. In the 1980s, early cladistic analyses found that they were Avemetatarsalians (archosaurs closer to dinosaurs than to crocodilians). As this would make them also rather close relatives of the dinosaurs, these results were seen by Kevin Padian as confirming his interpretation of pterosaurs as bipedal warm-blooded animals. Because these early analyses were based on a limited number of taxa and characters, their results were inherently uncertain. Several influential researchers who rejected Padian's conclusions offered alternative hypotheses. David Unwin proposed an ancestry among the basal Archosauromorpha, specifically long-necked forms ("Protorosauria, protorosaurs") such as tanystropheids. A placement among archosauriformes, basal archosauriforms like ''Euparkeria'' was also suggested. Some basal archosauromorphs seem at first glance to be good candidates for close pterosaur relatives due to their long-limbed anatomy; one example is ''Sharovipteryx'', a "protorosaur" with skin membranes on its hindlimbs likely used for gliding. A 1999 study by Michael Benton found that pterosaurs were avemetatarsalians closely related to ''Scleromochlus,'' and named the group Ornithodira to encompass pterosaurs and dinosaurs''.''

Two researchers, S. Christopher Bennett in 1996, and paleoartist David Peters in 2000, published analyses finding pterosaurs to be protorosaurs or closely related to them. However, Peters gathered novel anatomical data using an unverified technique called "Digital Graphic Segregation" (DGS), which involves digitally tracing over images of pterosaur fossils using photo editing software. Bennett only recovered pterosaurs as close relatives of the protorosaurs after removing characteristics of the hindlimb from his analysis, to test the possibility of locomotion-based convergent evolution between pterosaurs and dinosaurs. A 2007 reply by Dave Hone and Michael Benton could not reproduce this result, finding pterosaurs to be closely related to dinosaurs even without hindlimb characters. They also criticized David Peters for drawing conclusions without access to the primary evidence, that is, the pterosaur fossils themselves. Hone and Benton concluded that, although more basal pterosauromorphs are needed to clarify their relationships, current evidence indicates that pterosaurs are avemetatarsalians, as either the sister group of ''Scleromochlus'' or a branch between the latter and ''Lagosuchus''. An 2011 archosaur-focused phylogenetic analysis by Sterling Nesbitt benefited from far more data and found strong support for pterosaurs being avemetatarsalians, though ''Scleromochlus'' was not included due to its poor preservation. A 2016 archosauromorph-focused study by Martin Ezcurra included various proposed pterosaur relatives, yet also found pterosaurs to be closer to dinosaurs and unrelated to more basal taxa. Working from his 1996 analysis, Bennett published a 2020 study on ''Scleromochlus'' which argued that both ''Scleromochlus'' and pterosaurs were non-archosaur archosauromorphs, albeit not particularly closely related to each other. By contrast, a later 2020 study proposed that lagerpetid

Two researchers, S. Christopher Bennett in 1996, and paleoartist David Peters in 2000, published analyses finding pterosaurs to be protorosaurs or closely related to them. However, Peters gathered novel anatomical data using an unverified technique called "Digital Graphic Segregation" (DGS), which involves digitally tracing over images of pterosaur fossils using photo editing software. Bennett only recovered pterosaurs as close relatives of the protorosaurs after removing characteristics of the hindlimb from his analysis, to test the possibility of locomotion-based convergent evolution between pterosaurs and dinosaurs. A 2007 reply by Dave Hone and Michael Benton could not reproduce this result, finding pterosaurs to be closely related to dinosaurs even without hindlimb characters. They also criticized David Peters for drawing conclusions without access to the primary evidence, that is, the pterosaur fossils themselves. Hone and Benton concluded that, although more basal pterosauromorphs are needed to clarify their relationships, current evidence indicates that pterosaurs are avemetatarsalians, as either the sister group of ''Scleromochlus'' or a branch between the latter and ''Lagosuchus''. An 2011 archosaur-focused phylogenetic analysis by Sterling Nesbitt benefited from far more data and found strong support for pterosaurs being avemetatarsalians, though ''Scleromochlus'' was not included due to its poor preservation. A 2016 archosauromorph-focused study by Martin Ezcurra included various proposed pterosaur relatives, yet also found pterosaurs to be closer to dinosaurs and unrelated to more basal taxa. Working from his 1996 analysis, Bennett published a 2020 study on ''Scleromochlus'' which argued that both ''Scleromochlus'' and pterosaurs were non-archosaur archosauromorphs, albeit not particularly closely related to each other. By contrast, a later 2020 study proposed that lagerpetid

It was once thought that competition with early

It was once thought that competition with early

Another issue that has been difficult to understand is how they Takeoff, took off. Earlier suggestions were that pterosaurs were largely cold-blooded gliding animals, deriving warmth from the environment like modern lizards, rather than burning calories. In this case, it was unclear how the larger ones of enormous size, with an inefficient cold-blooded metabolism, could manage a bird-like takeoff strategy, using only the hind limbs to generate thrust for getting airborne. Later research shows them instead as being warm-blooded and having powerful flight muscles, and using the flight muscles for walking as quadrupeds. Mark Witton of the University of Portsmouth and Mike Habib of Johns Hopkins University suggested that pterosaurs used a vaulting mechanism to obtain flight. The tremendous power of their winged forelimbs would enable them to take off with ease. Once aloft, pterosaurs could reach speeds of up to and travel thousands of kilometres.

In 1985, the Smithsonian Institution commissioned aeronautical engineer Paul MacCready to build a half-scale working model of ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi''. The replica was launched with a ground-based winch. It flew several times in 1986 and was filmed as part of the Smithsonian's IMAX film ''On the Wing (1986 film), On the Wing''.

Large-headed species are thought to have Forward-swept wing, forwardly swept their wings in order to better balance.

Another issue that has been difficult to understand is how they Takeoff, took off. Earlier suggestions were that pterosaurs were largely cold-blooded gliding animals, deriving warmth from the environment like modern lizards, rather than burning calories. In this case, it was unclear how the larger ones of enormous size, with an inefficient cold-blooded metabolism, could manage a bird-like takeoff strategy, using only the hind limbs to generate thrust for getting airborne. Later research shows them instead as being warm-blooded and having powerful flight muscles, and using the flight muscles for walking as quadrupeds. Mark Witton of the University of Portsmouth and Mike Habib of Johns Hopkins University suggested that pterosaurs used a vaulting mechanism to obtain flight. The tremendous power of their winged forelimbs would enable them to take off with ease. Once aloft, pterosaurs could reach speeds of up to and travel thousands of kilometres.

In 1985, the Smithsonian Institution commissioned aeronautical engineer Paul MacCready to build a half-scale working model of ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi''. The replica was launched with a ground-based winch. It flew several times in 1986 and was filmed as part of the Smithsonian's IMAX film ''On the Wing (1986 film), On the Wing''.

Large-headed species are thought to have Forward-swept wing, forwardly swept their wings in order to better balance.

Pterosaurs' hip sockets are oriented facing slightly upwards, and the head of the femur (thigh bone) is only moderately inward facing, suggesting that pterosaurs had an erect stance. It would have been possible to lift the thigh into a horizontal position during flight, as gliding lizards do.

There was considerable debate whether pterosaurs ambulated as quadrupeds or as bipeds. In the 1980s, paleontologist Kevin Padian suggested that smaller pterosaurs with longer hindlimbs, such as ''

Pterosaurs' hip sockets are oriented facing slightly upwards, and the head of the femur (thigh bone) is only moderately inward facing, suggesting that pterosaurs had an erect stance. It would have been possible to lift the thigh into a horizontal position during flight, as gliding lizards do.

There was considerable debate whether pterosaurs ambulated as quadrupeds or as bipeds. In the 1980s, paleontologist Kevin Padian suggested that smaller pterosaurs with longer hindlimbs, such as '' Though traditionally depicted as ungainly and awkward when on the ground, the anatomy of some pterosaurs (particularly pterodactyloids) suggests that they were competent walkers and runners. Early pterosaurs have long been considered particularly cumbersome locomotors due to the presence of large Uropatagium, cruropatagia, but they too appear to have been generally efficient on the ground.

The forelimb bones of Azhdarchidae, azhdarchids and Ornithocheiridae, ornithocheirids were unusually long compared to other pterosaurs, and, in azhdarchids, the bones of the arm and hand (metacarpals) were particularly elongated. Furthermore, as a whole, azhdarchid front limbs were proportioned similarly to fast-running ungulate mammals. Their hind limbs, on the other hand, were not built for speed, but they were long compared with most pterosaurs, and allowed for a long stride length. While azhdarchid pterosaurs probably could not run, they would have been relatively fast and energy efficient.

The relative size of the hands and feet in pterosaurs (by comparison with modern animals such as birds) may indicate the type of lifestyle pterosaurs led on the ground. Azhdarchid pterosaurs had relatively small feet compared to their body size and leg length, with foot length only about 25–30% the length of the lower leg. This suggests that azhdarchids were better adapted to walking on dry, relatively solid ground. ''

Though traditionally depicted as ungainly and awkward when on the ground, the anatomy of some pterosaurs (particularly pterodactyloids) suggests that they were competent walkers and runners. Early pterosaurs have long been considered particularly cumbersome locomotors due to the presence of large Uropatagium, cruropatagia, but they too appear to have been generally efficient on the ground.

The forelimb bones of Azhdarchidae, azhdarchids and Ornithocheiridae, ornithocheirids were unusually long compared to other pterosaurs, and, in azhdarchids, the bones of the arm and hand (metacarpals) were particularly elongated. Furthermore, as a whole, azhdarchid front limbs were proportioned similarly to fast-running ungulate mammals. Their hind limbs, on the other hand, were not built for speed, but they were long compared with most pterosaurs, and allowed for a long stride length. While azhdarchid pterosaurs probably could not run, they would have been relatively fast and energy efficient.

The relative size of the hands and feet in pterosaurs (by comparison with modern animals such as birds) may indicate the type of lifestyle pterosaurs led on the ground. Azhdarchid pterosaurs had relatively small feet compared to their body size and leg length, with foot length only about 25–30% the length of the lower leg. This suggests that azhdarchids were better adapted to walking on dry, relatively solid ground. ''

While very little is known about pterosaur reproduction, it is believed that, similar to all dinosaurs, all pterosaurs reproduced by laying eggs, though such findings are very rare. The first known pterosaur egg was found in the quarries of Liaoning, the same place that yielded feathered dinosaurs. The egg was squashed flat with no signs of cracking, so evidently the eggs had leathery shells, as in modern lizards. This was supported by the description of an additional pterosaur egg belonging to the genus ''Darwinopterus'', described in 2011, which also had a leathery shell and, also like modern reptiles but unlike birds, was fairly small compared to the size of the mother. In 2014 five unflattened eggs from the species ''Hamipterus, Hamipterus tianshanensis'' were found in an Early Cretaceous deposit in northwest China. Examination of the shells by scanning electron microscopy showed the presence of a thin calcareous eggshell layer with a membrane underneath. A study of pterosaur eggshell structure and chemistry published in 2007 indicated that it is likely pterosaurs buried their eggs, like modern crocodiles and turtles. Egg-burying would have been beneficial to the early evolution of pterosaurs, as it allows for more weight-reducing adaptations, but this method of reproduction would also have put limits on the variety of environments pterosaurs could live in, and may have disadvantaged them when they began to face ecological competition from

While very little is known about pterosaur reproduction, it is believed that, similar to all dinosaurs, all pterosaurs reproduced by laying eggs, though such findings are very rare. The first known pterosaur egg was found in the quarries of Liaoning, the same place that yielded feathered dinosaurs. The egg was squashed flat with no signs of cracking, so evidently the eggs had leathery shells, as in modern lizards. This was supported by the description of an additional pterosaur egg belonging to the genus ''Darwinopterus'', described in 2011, which also had a leathery shell and, also like modern reptiles but unlike birds, was fairly small compared to the size of the mother. In 2014 five unflattened eggs from the species ''Hamipterus, Hamipterus tianshanensis'' were found in an Early Cretaceous deposit in northwest China. Examination of the shells by scanning electron microscopy showed the presence of a thin calcareous eggshell layer with a membrane underneath. A study of pterosaur eggshell structure and chemistry published in 2007 indicated that it is likely pterosaurs buried their eggs, like modern crocodiles and turtles. Egg-burying would have been beneficial to the early evolution of pterosaurs, as it allows for more weight-reducing adaptations, but this method of reproduction would also have put limits on the variety of environments pterosaurs could live in, and may have disadvantaged them when they began to face ecological competition from

Pterosaurs have been a staple of popular culture for as long as their cousins the dinosaurs, though they are usually not featured as prominently in films, literature or other art. While the depiction of dinosaurs in popular media has changed radically in response to advances in paleontology, a mainly outdated picture of pterosaurs has persisted since the mid-20th century.

The vague generic term "pterodactyl" is often used for these creatures. The animals depicted in fiction and pop culture frequently represent either the ''

Pterosaurs have been a staple of popular culture for as long as their cousins the dinosaurs, though they are usually not featured as prominently in films, literature or other art. While the depiction of dinosaurs in popular media has changed radically in response to advances in paleontology, a mainly outdated picture of pterosaurs has persisted since the mid-20th century.

The vague generic term "pterodactyl" is often used for these creatures. The animals depicted in fiction and pop culture frequently represent either the ''

"Pterosaurs In Popular Culture."

''Pterosaur.net'', Accessed 27 August 2010. Many children's toys and cartoons feature "pterodactyls" with ''Pteranodon''-like crests and long, ''Rhamphorhynchus (animal), Rhamphorhynchus''-like tails and teeth, a combination that never existed in nature. However, at least one pterosaur ''did'' have both the ''Pteranodon''-like crest and teeth: ''Ludodactylus'', whose name means "toy finger" for its resemblance to old, inaccurate children's toys.Frey, E., Martill, D., and Buchy, M. (2003). "A new crested ornithocheirid from the Lower Cretaceous of northeastern Brazil and the unusual death of an unusual pterosaur" in: Buffetaut, E., and Mazin, J.-M. (eds.). ''Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs''. ''Geological Society Special Publication'' 217: 56–63. . Pterosaurs have sometimes been incorrectly identified as (the ancestors of)

"The One Born of Fire: a pterosaurological analysis of Rodan"

''Journal of Geek Studies'' 7: 53–59. Rodan has appeared in multiple Japanese Godzilla (franchise), ''Godzilla'' films released during the 1960s, 1970s, 1990s, and 2000s, and also appeared in the 2019 American-produced film ''Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019 film), Godzilla: King of the Monsters''. After the 1960s, pterosaurs remained mostly absent from notable American film appearances until 2001's ''Jurassic Park III''. Paleontologist Dave Hone noted that the pterosaurs in this film had not been significantly updated to reflect modern research. Errors persisting were teeth while toothless ''Pteranodon'' was intended to be depicted, nesting behavior that was known to be inaccurate by 2001, and leathery wings, rather than the taut membranes of muscle fiber required for pterosaur flight. Petrie from ''The Land Before Time'' (1988), is a notable example from an animated film. In most media appearances, pterosaurs are depicted as piscivores, not reflecting their full dietary variation. They are also often shown as aerial predators similar to Bird of prey, birds of prey, grasping human victims with talons on their feet. However, only the small anurognathid ''

Pterosaur.net

multi-authored website about all aspects of pterosaur science

The Pterosaur Database

by Paul Pursglove

by Alexander W. A. Kellner (technical) {{Authority control Pterosaurs, Late Triassic first appearances Maastrichtian extinctions Pterosauromorpha

clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

of flying reptiles

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchoceph ...

in the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

: from the Late Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

to the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

(228 to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earliest vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with ...

s known to have evolved powered flight. Their wings were formed by a membrane of skin, muscle, and other tissues stretching from the ankles to a dramatically lengthened fourth finger.

There were two major types of pterosaurs. Basal pterosaurs (also called 'non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs' or 'rhamphorhynchoid

The Rhamphorhynchoidea forms one of the two suborders of pterosaurs and represents an evolutionary grade of primitive members of flying reptiles. This suborder is paraphyletic unlike the Pterodactyloidea, which arose from within the Rhamphorhync ...

s') were smaller animals with fully toothed jaws and, typically, long tails. Their wide wing membranes probably included and connected the hind legs. On the ground, they would have had an awkward sprawling posture, but the anatomy of their joints and strong claws would have made them effective climbers, and some may have even lived in trees. Basal pterosaurs were insectivore

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant that eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores were ...

s or predators of small vertebrates. Later pterosaurs (pterodactyloid

Pterodactyloidea (derived from the Greek words ''πτερόν'' (''pterón'', for usual ''ptéryx'') "wing", and ''δάκτυλος'' (''dáktylos'') "finger" meaning "winged finger", "wing-finger" or "finger-wing") is one of the two traditional ...

s) evolved many sizes, shapes, and lifestyles. Pterodactyloids had narrower wings with free hind limbs, highly reduced tails, and long necks with large heads. On the ground, pterodactyloids walked well on all four limbs with an upright posture, standing plantigrade

151px, Portion of a human skeleton, showing plantigrade habit

In terrestrial animals, plantigrade locomotion means walking with the toes and metatarsals flat on the ground. It is one of three forms of locomotion adopted by terrestrial mammals. ...

on the hind feet and folding the wing finger upward to walk on the three-fingered "hand". They could take off from the ground, and fossil trackways show at least some species were able to run and wade or swim. Their jaws had horny beaks, and some groups lacked teeth. Some groups developed elaborate head crests with sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

.

Pterosaurs sported coats of hair-like filaments known as pycnofibers

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to 6 ...

, which covered their bodies and parts of their wings. Pycnofibers grew in several forms, from simple filaments to branching down feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premie ...

s. These may be homologous to the down feathers found on both avian

Avian may refer to:

* Birds or Aves, winged animals

*Avian (given name) (russian: Авиа́н, link=no), a male forename

Aviation

*Avro Avian, a series of light aircraft made by Avro in the 1920s and 1930s

*Avian Limited, a hang glider manufactur ...

and some non-avian dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is the ...

, suggesting that early feathers evolved in the common ancestor of pterosaurs and dinosaurs, possibly as insulation. In life, pterosaurs would have had smooth or fluffy coats that did not resemble bird feathers. They were warm-blooded (endothermic), active animals. The respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies g ...

had efficient unidirectional "flow-through" breathing using air sacs

Air sacs are spaces within an organism where there is the constant presence of air. Among modern animals, birds possess the most air sacs (9–11), with their extinct dinosaurian relatives showing a great increase in the pneumatization (presence o ...

, which hollowed out their bones to an extreme extent. Pterosaurs spanned a wide range of adult sizes, from the very small anurognathids to the largest known flying creatures, including ''Quetzalcoatlus

''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a genus of pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous period of North America (Maastrichtian stage); its members were among the largest known flying animals of all time. ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a member of the Azhdarchidae, ...

'' and ''Hatzegopteryx

''Hatzegopteryx'' (" Hațeg basin wing") is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur found in the late Maastrichtian deposits of the Densuş Ciula Formation, an outcropping in Transylvania, Romania. It is known only from the type species, ''Hatzegopter ...

'', which reached wingspans of at least nine metres. The combination of endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

, a good oxygen supply and strong muscles made pterosaurs powerful and capable flyers.

Pterosaurs are often referred to by popular media or the general public as "flying dinosaurs", but dinosaurs are defined as the descendants of the last common ancestor of the Saurischia

Saurischia ( , meaning "reptile-hipped" from the Greek ' () meaning 'lizard' and ' () meaning 'hip joint') is one of the two basic divisions of dinosaurs (the other being Ornithischia), classified by their hip structure. Saurischia and Ornithis ...

and Ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

, which excludes the pterosaurs. Pterosaurs are nonetheless more closely related to birds and other dinosaurs than to crocodiles or any other living reptile, though they are not bird ancestors. Pterosaurs are also colloquially referred to as pterodactyls, particularly in fiction and journalism. However, technically, ''pterodactyl'' may refer to members of the genus ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

'', and more broadly to members of the suborder Pterodactyloidea

Pterodactyloidea (derived from the Greek words ''πτερόν'' (''pterón'', for usual ''ptéryx'') "wing", and ''δάκτυλος'' (''dáktylos'') "finger" meaning "winged finger", "wing-finger" or "finger-wing") is one of the two traditional ...

of the pterosaurs.

Pterosaurs had a variety of lifestyles. Traditionally seen as fish-eaters, the group is now understood to have also included hunters of land animals, insectivores, fruit eaters and even predators of other pterosaurs. They reproduced by eggs, some fossils of which have been discovered.

Description

The anatomy of pterosaurs was highly modified from their reptilian ancestors by the adaptation to flight. Pterosaur bones were hollow and air-filled, like those ofbird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s. This provided a higher muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of mus ...

attachment surface for a given skeletal weight. The bone walls were often paper-thin. They had a large and keeled breastbone for flight muscles and an enlarged brain

A brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as Visual perception, vision. I ...

able to coordinate complex flying behaviour. Pterosaur skeletons often show considerable fusion. In the skull, the suture

Suture, literally meaning "seam", may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Suture'' (album), a 2000 album by American Industrial rock band Chemlab

* ''Suture'' (film), a 1993 film directed by Scott McGehee and David Siegel

* Suture (ban ...

s between elements disappeared. In some later pterosaurs, the backbone over the shoulders fused into a structure known as a notarium, which served to stiffen the torso during flight, and provide a stable support for the shoulder blade

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either ...

. Likewise, the sacral vertebrae could form a single synsacrum while the pelvic bones fused also.

Basal pterosaurs include the clades Dimorphodontidae (''Dimorphodon

''Dimorphodon'' was a genus of medium-sized pterosaur from the early Jurassic Period. It was named by paleontologist Richard Owen in 1859. ''Dimorphodon'' means "two-form tooth", derived from the Greek (') meaning "two", (') meaning "shape" ...

''), Campylognathididae (''Eudimorphodon

''Eudimorphodon'' was a pterosaur that was discovered in 1973 by Mario Pandolfi in the town of Cene, Italy and described the same year by Rocco Zambelli. The nearly complete skeleton was retrieved from shale deposited during the Late Triassic (m ...

'', '' Campyognathoides''), and Rhamphorhynchidae (''Rhamphorhynchus

''Rhamphorhynchus'' (, from Ancient Greek ''rhamphos'' meaning "beak" and ''rhynchus'' meaning "snout") is a genus of long-tailed pterosaurs in the Jurassic period. Less specialized than contemporary, short-tailed pterodactyloid pterosaurs such ...

'', ''Scaphognathus

''Scaphognathus'' was a pterosaur that lived around Germany during the Late Jurassic. It had a wingspan of 0.9 m (3 ft).

Naming

The first known ''Scaphognathus'' specimen was described in 1831 by August Goldfuss who mistook the taill ...

'').

Pterodactyloids include the clades Ornithocheiroidea (''Istiodactylus

''Istiodactylus'' is a genus of pterosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous period, about 120 million years ago. The first fossil was discovered on the English Isle of Wight in 1887, and in 1901 became the holotype specimen of a new species ...

'', ''Ornithocheirus

''Ornithocheirus'' (from Ancient Greek "ὄρνις", meaning ''bird'', and "χεῖρ", meaning ''hand'') is a pterosaur genus known from fragmentary fossil remains uncovered from sediments in the UK and possibly Morocco.

Several species have ...

'', ''Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (); from Ancient Greek (''pteron'', "wing") and (''anodon'', "toothless") is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of . They lived during the late Cr ...

''), Ctenochasmatoidea (''Ctenochasma

''Ctenochasma'' (meaning "comb jaw") is a genus of Late Jurassic ctenochasmatid pterosaur belonging to the suborder Pterodactyloidea. Three species are currently recognized: ''C. roemeri'' (named after Friedrich Adolph Roemer), ''C. taqueti'', a ...

'', ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

''), Dsungaripteroidea ('' Germanodactylus'', '' Dsungaripterus''), and Azhdarchoidea ('' Tapejara'', ''Tupuxuara

''Tupuxuara'' is a genus of large, crested, and toothless pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous period (Albian stage) of what is now the Romualdo Formation of the Santana Group, Brazil, about 125 to 112 million years ago. ''Tupuxu ...

'', ''Quetzalcoatlus

''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a genus of pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous period of North America (Maastrichtian stage); its members were among the largest known flying animals of all time. ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a member of the Azhdarchidae, ...

'').

The two groups overlapped in time, but the earliest pterosaurs in the fossil record are basal pterosaurs, and the latest pterosaurs are pterodactyloids.

The position of the clade Anurognathidae (''Anurognathus

''Anurognathus'' is a genus of small pterosaur that lived during the Late Jurassic period ( Tithonian stage). ''Anurognathus'' was first named and described by Ludwig Döderlein in 1923.Döderlein, L. (1923). "''Anurognathus Ammoni'', ein neue ...

, Jeholopterus

''Jeholopterus'' was a small anurognathid pterosaur from the Middle to Late Jurassic Daohugou Beds of the Tiaojishan Formation of Inner Mongolia, China, preserved with hair-like pycnofibres and skin remains.

Naming

The genus was named in 20 ...

, Vesperopterylus

''Vesperopterylus'' (meaning "dusk wing") is a genus of anurognathid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of China, the geologically youngest member of its group. Notably, ''Vesperopterylus'' appears to have a reversed first ...

'') is debated. Anurognathids (frog-headed pterosaurs) were highly specialized. Small flyers with shortened jaws and a wide gape, some had large eyes suggesting nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

or crepuscular

In zoology, a crepuscular animal is one that is active primarily during the twilight period, being matutinal, vespertine, or both. This is distinguished from diurnal and nocturnal behavior, where an animal is active during the hours of dayli ...

habits, mouth bristles, and feet adapted for clinging. Parallel adaptations are seen in birds and bats that prey on insects in flight.

Size

Pterosaurs had a wide range of sizes, though they were generally large. The smallest species had a wingspan no less than . The most sizeable forms represent the largest known animals ever to fly, with wingspans of up to . Standing, such giants could reach the height of a moderngiraffe

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, '' Giraffa camelopardal ...

. Traditionally, it was assumed that pterosaurs were extremely light relative to their size. Later, it was understood that this would imply unrealistically low densities of their soft tissues. Some modern estimates therefore extrapolate a weight of up to for the largest species.

Skull, teeth, and crests

Compared to the other vertebrate flying groups, the birds and bats, pterosaur skulls were typically quite large. Most pterosaur skulls had elongated jaws. Their skull bones tend to be fused in adult individuals. Early pterosaurs often had

Compared to the other vertebrate flying groups, the birds and bats, pterosaur skulls were typically quite large. Most pterosaur skulls had elongated jaws. Their skull bones tend to be fused in adult individuals. Early pterosaurs often had heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For exampl ...

teeth, varying in build, and some still had teeth in the palate. In later groups the teeth mostly became conical. Front teeth were often longer, forming a "prey grab" in transversely expanded jaw tips, but size and position were very variable among species. With the derived Pterodactyloidea

Pterodactyloidea (derived from the Greek words ''πτερόν'' (''pterón'', for usual ''ptéryx'') "wing", and ''δάκτυλος'' (''dáktylos'') "finger" meaning "winged finger", "wing-finger" or "finger-wing") is one of the two traditional ...

, the skulls became even more elongated, sometimes surpassing the combined neck and torso in length. This was caused by a stretching and fusion of the front snout bone, the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

, with the upper jaw bone, the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

. Unlike most archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avia ...

s, the nasal and antorbital openings of pterodactyloid pterosaurs merged into a single large opening, called the ''nasoantorbital fenestra''. This feature likely evolved to lighten the skull for flight. In contrast, the bones behind the eye socket contracted and rotated, strongly inclining the rear skull and bringing the jaw joint forward. The braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, or brain-pan is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calvaria or skul ...

was relatively large for reptiles.

In some cases, fossilized

In some cases, fossilized keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail ...

ous beak tissue has been preserved, though in toothed forms, the beak is small and restricted to the jaw tips and does not involve the teeth. Some advanced beaked forms were toothless, such as the Pteranodontidae

The Pteranodontidae are a family of large pterosaurs of the Cretaceous Period of North America and Africa. The family was named in 1876 by Othniel Charles Marsh. Pteranodontids had a distinctive, elongated crest jutting from the rear of the head ( ...

and Azhdarchidae

Azhdarchidae (from the Persian word , , a dragon-like creature in Persian mythology) is a family of pterosaurs known primarily from the Late Cretaceous Period, though an isolated vertebra apparently from an azhdarchid is known from the Early C ...

, and had larger, more extensive, and more bird-like beaks. Some groups had specialised tooth forms. The Istiodactylidae

Istiodactylidae is a small family of pterosaurs. This family was named in 2001 after the type genus ''Istiodactylus'' was discovered not to be a member of the genus '' Ornithodesmus''.

Systematics and distribution

Remains of taxa that can be ...

had recurved teeth for eating meat. Ctenochasmatidae

Ctenochasmatidae is a group of pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea. They are characterized by their distinctive teeth, which are thought to have been used for filter-feeding. Ctenochasmatids lived from the Late Jurassic to the Early C ...

used combs of numerous needle-like teeth for filter feeding; ''Pterodaustro

''Pterodaustro'' is a genus of ctenochasmatid pterodactyloid pterosaur from South America. Its fossil remains dated back to the Early Cretaceous period, about 105 million years ago. The most distinctive characteristic that separates ''Pterodaus ...

'' could have over a thousand bristle-like teeth. Dsungaripteridae

Dsungaripteridae is a group of pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea. They were robust pterosaurs with good terrestrial abilities and flight honed for inland settings.

Classification

In 1964 Young created a family to place the recently ...

covered their teeth with jawbone tissue for a crushing function. If teeth were present, they were placed in separate tooth sockets. Replacement teeth were generated behind, not below, the older teeth.

The public image of pterosaurs is defined by their elaborate head crests. This was influenced by the distinctive backward-pointing crest of the well-known ''

The public image of pterosaurs is defined by their elaborate head crests. This was influenced by the distinctive backward-pointing crest of the well-known ''Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (); from Ancient Greek (''pteron'', "wing") and (''anodon'', "toothless") is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of . They lived during the late Cr ...

''. The main positions of such crests are the front of the snout, as an outgrowth of the premaxillae, or the rear of the skull as an extension of the parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, and four angles. It is n ...

s in which case it is called a "supraoccipital crest". Front and rear crests can be present simultaneously and might be fused into a single larger structure, the most expansive of which is shown by the Tapejaridae

Tapejaridae (from a Tupi word meaning "the old being") are a family of pterodactyloid pterosaurs from the Cretaceous period. Members are currently known from Brazil, England, Hungary, Morocco, Spain, the United States, and China. The most primi ...

. '' Nyctosaurus'' sported a bizarre antler-like crest. The crests were only a few millimetres thin transversely. The bony crest base would typically be extended by keratinous or other soft tissue.

Since the 1990s, new discoveries and a more thorough study of old specimens have shown that crests are far more widespread among pterosaurs than previously assumed. That they were extended by or composed completely of keratin, which does not fossilize easily, had misled earlier research. For ''Pterorhynchus

''Pterorhynchus'' ("wing snout") is an extinct genus of pterosaur from the mid- Jurassic aged Daohugou Formation of Inner Mongolia, China.

The genus was named in 2002 by Stephen Czerkas and Ji Qiang. The type species is ''Pterorhynchus welln ...

'' and ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

'', the true extent of these crests has only been uncovered using ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

photography.Czerkas, S.A., and Ji, Q. (2002). A new rhamphorhynchoid with a headcrest and complex integumentary structures. In: Czerkas, S.J. (Ed.). ''Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight''. The Dinosaur Museum: Blanding, Utah, 15–41. . While fossil crests used to be restricted to the more advanced Pterodactyloidea, ''Pterorhynchus'' and ''Austriadactylus

''Austriadactylus'' is a genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur. The fossil remains were unearthed in Late Triassic (middle Norian ageBarrett, P. M., Butler, R. J., Edwards, N. P., & Milner, A. R. (2008). Pterosaur distribution in time and space: ...

'' show that even some early pterosaurs possessed them.

Like the upper jaws, the paired lower jaws of pterosaurs were very elongated. In advanced forms, they tended to be shorter than the upper cranium because the jaw joint was in a more forward position. The front lower jaw bones, the dentaries or ''ossa dentalia'', were at the tip tightly fused into a central symphysis. This made the lower jaws function as a single connected whole, the mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

. The symphysis was often very thin transversely and long, accounting for a considerable part of the jaw length, up to 60%. If a crest was present on the snout, the symphysis could feature a matching mandible crest, jutting out to below. Toothed species also bore teeth in their dentaries. The mandible opened and closed in a simple vertical or "orthal" up-and-down movement.

Vertebral column

vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

of pterosaurs numbered between thirty-four and seventy vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

. The vertebrae in front of the tail were "procoelous": the cotyle (front of the vertebral body) was concave and into it fitted a convex extension at the rear of the preceding vertebra, the condyle

A condyle (;Entry "condyle"

in

exapophyses Exapophyses (singular: Exapophysis) are bony joints present in the cervicals (neck vertebrae) of some pterosaurs. Exapophyses lie on the centrum, the spool-shaped main body of each vertebra, where they are positioned adjacent to the main articulatin ...

, and the cotyle also may possess a small prong on its midline called a hypapophysis.

in

exapophyses Exapophyses (singular: Exapophysis) are bony joints present in the cervicals (neck vertebrae) of some pterosaurs. Exapophyses lie on the centrum, the spool-shaped main body of each vertebra, where they are positioned adjacent to the main articulatin ...

The neck of pterosaurs was relatively long and straight. In pterodactyloids, the neck is typically longer than the torso. This length is not caused by an increase of the number of vertebrae, which is invariably seven. Some researchers include two transitional "cervicodorsals" which brings the number to nine. Instead, the vertebrae themselves became more elongated, up to eight times longer than wide. Nevertheless, the cervicals were wider than high, implying a better vertical than horizontal neck mobility. Pterodactyloids have lost all neck ribs. Pterosaur necks were probably rather thick and well-muscled, especially vertically.

The torso was relatively short and egg-shaped. The vertebrae in the back of pterosaurs originally might have numbered eighteen. With advanced species a growing number of these tended to be incorporated into the

The neck of pterosaurs was relatively long and straight. In pterodactyloids, the neck is typically longer than the torso. This length is not caused by an increase of the number of vertebrae, which is invariably seven. Some researchers include two transitional "cervicodorsals" which brings the number to nine. Instead, the vertebrae themselves became more elongated, up to eight times longer than wide. Nevertheless, the cervicals were wider than high, implying a better vertical than horizontal neck mobility. Pterodactyloids have lost all neck ribs. Pterosaur necks were probably rather thick and well-muscled, especially vertically.

The torso was relatively short and egg-shaped. The vertebrae in the back of pterosaurs originally might have numbered eighteen. With advanced species a growing number of these tended to be incorporated into the sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part o ...

. Such species also often show a fusion of the front dorsal vertebrae into a rigid whole which is called the notarium after a comparable structure in birds. This was an adaptation to withstand the forces caused by flapping the wings. The notarium included three to seven vertebrae, depending on the species involved but also on individual age. These vertebrae could be connected by tendons or a fusion of their neural spines into a "supraneural plate". Their ribs also would be tightly fused into the notarium. In general, the ribs are double-headed. The sacrum consisted of three to ten sacral vertebrae. They too, could be connected via a supraneural plate that, however, would not contact the notarium.

chevron

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* '' Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock la ...

s. Such tails acted as rudders, sometimes ending at the rear in a vertical diamond-shaped or oval vane. In pterodactyloids, the tails were much reduced and never stiffened, with some species counting as few as ten vertebrae.

Shoulder girdle

The

The shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists ...

was a strong structure that transferred the forces of flapping flight to the thorax

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the c ...

. It was probably covered by thick muscle layers. The upper bone, the shoulder blade

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either ...

, was a straight bar. It was connected to a lower bone, the coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

that is relatively long in pterosaurs. In advanced species, their combined whole, the scapulocoracoid, was almost vertically oriented. The shoulder blade in that case fitted into a recess in the side of the notarium, while the coracoid likewise connected to the breastbone. This way, both sides together made for a rigid closed loop, able to withstand considerable forces. A peculiarity was that the breastbone connections of the coracoids often were asymmetrical, with one coracoid attached in front of the other. In advanced species the shoulder joint had moved from the shoulder blade to the coracoid. The joint was saddle-shaped and allowed considerable movement to the wing. It faced sideways and somewhat upwards.

The breastbone, formed by fused paired ''sterna'', was wide. It had only a shallow keel. Via sternal ribs, it was at its sides attached to the dorsal ribs. At its rear, a row of belly ribs or gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In thes ...

was present, covering the entire belly. To the front, a long point, the ''cristospina'', jutted obliquely upwards. The rear edge of the breastbone was the deepest point of the thorax. Clavicles or interclavicles were completely absent.

Wings

Pterosaur wings were formed by bones and membranes of skin and other tissues. The primary membranes attached to the extremely long fourth

Pterosaur wings were formed by bones and membranes of skin and other tissues. The primary membranes attached to the extremely long fourth finger

A finger is a limb of the body and a type of digit, an organ of manipulation and sensation found in the hands of most of the Tetrapods, so also with humans and other primates. Most land vertebrates have five fingers ( Pentadactyly). Chamber ...

of each arm and extended along the sides of the body. Where they ended has been very controversial but since the 1990s a dozen specimens with preserved soft tissue have been found that seem to show they attached to the ankles. The exact curvature of the trailing edge, however, is still equivocal.

While historically thought of as simple leathery structures composed of skin, research has since shown that the wing membranes of pterosaurs were highly complex dynamic structures suited to an active style of flight. The outer wings (from the tip to the elbow) were strengthened by closely spaced fibers called ''