Prudence Crandall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Prudence Crandall (September 3, 1803 – January 27, 1890) was an American schoolteacher and activist. She ran the first school for black girls ("young Ladies and little Misses of color") in the United States, located in

Although Prudence Crandall grew up as a North American Quaker, she admitted that she was not acquainted with many black people or abolitionists. She discovered the problems that plagued black people through the abolitionist newspaper '' The Liberator'', which she learned of through her housekeeper, "a young black lady", whose fiancé was the son of the paper's local agent. After reading ''The Liberator'', Prudence Crandall said in an earlier account that she "contemplated for a while, the manner in which I might best serve the people of color."

Prudence Crandall's chance to help people of color came in the fall of 1832. Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free African-American farmer near Canterbury, asked to be accepted to the school to prepare for teaching other African Americans. Although Crandall was uncertain about whether to admit Harris, whom she liked, she consulted her Bible, which, as she told it, came open to Ecclesiastes 4:1:

She then admitted the girl, establishing the first integrated school in the United States. Prominent townspeople objected and placed pressure on Crandall to dismiss Harris from the school, but she refused. Although the white students in the school did not openly oppose the presence of Sarah Harris, families of the current white students removed their daughters from the school.

Consequently, Crandall devoted herself to teaching African-American girls, after traveling to Boston to consult with abolitionists Samuel J. May and

Although Prudence Crandall grew up as a North American Quaker, she admitted that she was not acquainted with many black people or abolitionists. She discovered the problems that plagued black people through the abolitionist newspaper '' The Liberator'', which she learned of through her housekeeper, "a young black lady", whose fiancé was the son of the paper's local agent. After reading ''The Liberator'', Prudence Crandall said in an earlier account that she "contemplated for a while, the manner in which I might best serve the people of color."

Prudence Crandall's chance to help people of color came in the fall of 1832. Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free African-American farmer near Canterbury, asked to be accepted to the school to prepare for teaching other African Americans. Although Crandall was uncertain about whether to admit Harris, whom she liked, she consulted her Bible, which, as she told it, came open to Ecclesiastes 4:1:

She then admitted the girl, establishing the first integrated school in the United States. Prominent townspeople objected and placed pressure on Crandall to dismiss Harris from the school, but she refused. Although the white students in the school did not openly oppose the presence of Sarah Harris, families of the current white students removed their daughters from the school.

Consequently, Crandall devoted herself to teaching African-American girls, after traveling to Boston to consult with abolitionists Samuel J. May and

Jennifer Rycenga gives a talk on Prudence Crandall, 2018

April 14, 2018, Otis Library, Norwich, Connecticut. Rycenga has published an article on Crandall (reference above) and is at work on a biography.

''"From Canterbury to Little Rock: The Struggle for Educational Equality for African Americans"'', a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

*

"Hezekiah Crandall"

(sister), Find a Grave. * Find a Grave {{DEFAULTSORT:Crandall, Prudence 1803 births 1890 deaths People from Hopkinton, Rhode Island American Quakers Activists for African-American civil rights American educators School desegregation pioneers Symbols of Connecticut Education in Connecticut People from Canterbury, Connecticut People from Washington County, Rhode Island American suffragists African-American history of Connecticut African Americans and education Moses Brown School alumni Prudence Crandall Women civil rights activists American school principals Founders of schools in the United States

Canterbury, Connecticut

Canterbury is a New England town, town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 5,045 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census.

History

The area was settled by English colonists in the 1680s as ''Peagscomsuck''. It c ...

.

When Crandall admitted Sarah Harris, a 20-year-old African-American female student in 1832 to her school,Wormley, G. Smith. ''The Journal of Negro History'', "Prudence Crandall", Vol. 8, No. 1, January 1923, pp. 72–80. Tisler, C.C. "Prudence Crandall, Abolitionist", ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984)'', Vol. 33, No. 2, June 1940, pp. 203–206. she had what is considered the first integrated classroom in the United States. Parents of the white children began to withdraw them. Prudence was a "very obstinate girl", according to her brother Reuben. Rather than ask the African-American student to leave, she decided that if white girls would not attend with the black students, she would educate black girls. She was arrested and spent a night in jail. Soon the violence of the townspeople forced her to close the school. She left Connecticut and never lived there again.

Much later the Connecticut legislature

The Connecticut General Assembly (CGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is a bicameral body composed of the 151-member House of Representatives and the 36-member Senate. It meets in the state capital, Hartford. Ther ...

, with lobbying from Mark Twain, a resident of Hartford

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since t ...

, passed a resolution honoring Crandall and providing her with a pension. Twain offered to buy her former Canterbury home for her retirement, but she declined. She died a few years later, in 1890.

In 1995 the Connecticut General Assembly

The Connecticut General Assembly (CGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is a bicameral body composed of the 151-member House of Representatives and the 36-member Senate. It meets in the state capital, Hartford. Th ...

named her the Official Heroine of Connecticut.

Early life

Prudence Crandall was born on September 3, 1803, to Pardon and Esther Carpenter Crandall, a Quaker couple who lived in Carpenter's Mills, Rhode Island. Reuben was her younger brother. When she was about 10, her father moved the family to nearbyCanterbury, Connecticut

Canterbury is a New England town, town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 5,045 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census.

History

The area was settled by English colonists in the 1680s as ''Peagscomsuck''. It c ...

. As her father thought little of the local public school, he paid for her to attend the Black Hill Quaker School in Plainfield, east of Canterbury. Her teacher there, Rowland Greene, was opposed to slavery, and much later gave an address, published in William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

's ''The Liberator'', on the necessity of education for blacks, and commended Isaac C. Glasgow for sending two of his daughters, "exemplary young women", to Crandall's school for young ladies of color.

When 22, for one year she attended the New England Yearly Meeting School, a Quaker boarding school in Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. One of the oldest cities in New England, it was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian and religious exile from the Massachusetts ...

. That the school existed was due to the generosity of Moses Brown

Moses Brown (September 23, 1738 – September 6, 1836) was an American abolitionist and industrialist from New England, who funded the design and construction of some of the first factory houses for spinning machines during the American industr ...

, an abolitionist and co-founder of Brown University; in 1904 the school renamed itself the Moses Brown School

Moses Brown School is an independent Quaker school located in Providence, Rhode Island, offering pre-kindergarten through secondary school classes. It was founded in 1784 by Moses Brown, a Quaker abolitionist, and is one of the oldest prepara ...

. After graduating, Prudence Crandall taught a school in Plainfield."The Drama of Prudence Crandall." Prudence Crandall Collection, Box 3. ''Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives'', Connecticut College. She became a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

in 1830.

Establishment of the boarding school

In 1831 she purchased theElisha Payne

Elisha Payne (7 March 1731 – 20 July 1807) was a prominent businessman and political figure in the states of New Hampshire and Vermont following the events of the American Revolution. He is best known for serving as Lieutenant Governor of t ...

house, with her sister Almira Crandall, to establish the Canterbury Female Boarding School

The Canterbury Female Boarding School, in Canterbury, Connecticut, was operated by its founder, Prudence Crandall, from 1831 to 1834. When townspeople would not allow African-American girls to enroll, Crandall decided to turn it into a school for ...

, at the request of Canterbury's aristocratic residents, to educate young girls in the town. With the help of her sister and a maid, she taught about forty children in different subjects including geography, history, grammar, arithmetic, reading, and writing. As principal of the female boarding school, Prudence Crandall was deemed successful in her ability to educate young girls, and the school flourished until September 1832.

Integration of the boarding school

Although Prudence Crandall grew up as a North American Quaker, she admitted that she was not acquainted with many black people or abolitionists. She discovered the problems that plagued black people through the abolitionist newspaper '' The Liberator'', which she learned of through her housekeeper, "a young black lady", whose fiancé was the son of the paper's local agent. After reading ''The Liberator'', Prudence Crandall said in an earlier account that she "contemplated for a while, the manner in which I might best serve the people of color."

Prudence Crandall's chance to help people of color came in the fall of 1832. Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free African-American farmer near Canterbury, asked to be accepted to the school to prepare for teaching other African Americans. Although Crandall was uncertain about whether to admit Harris, whom she liked, she consulted her Bible, which, as she told it, came open to Ecclesiastes 4:1:

She then admitted the girl, establishing the first integrated school in the United States. Prominent townspeople objected and placed pressure on Crandall to dismiss Harris from the school, but she refused. Although the white students in the school did not openly oppose the presence of Sarah Harris, families of the current white students removed their daughters from the school.

Consequently, Crandall devoted herself to teaching African-American girls, after traveling to Boston to consult with abolitionists Samuel J. May and

Although Prudence Crandall grew up as a North American Quaker, she admitted that she was not acquainted with many black people or abolitionists. She discovered the problems that plagued black people through the abolitionist newspaper '' The Liberator'', which she learned of through her housekeeper, "a young black lady", whose fiancé was the son of the paper's local agent. After reading ''The Liberator'', Prudence Crandall said in an earlier account that she "contemplated for a while, the manner in which I might best serve the people of color."

Prudence Crandall's chance to help people of color came in the fall of 1832. Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free African-American farmer near Canterbury, asked to be accepted to the school to prepare for teaching other African Americans. Although Crandall was uncertain about whether to admit Harris, whom she liked, she consulted her Bible, which, as she told it, came open to Ecclesiastes 4:1:

She then admitted the girl, establishing the first integrated school in the United States. Prominent townspeople objected and placed pressure on Crandall to dismiss Harris from the school, but she refused. Although the white students in the school did not openly oppose the presence of Sarah Harris, families of the current white students removed their daughters from the school.

Consequently, Crandall devoted herself to teaching African-American girls, after traveling to Boston to consult with abolitionists Samuel J. May and William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

about the project. (Both were supportive, and gave her letters of introduction to prominent African Americans in locations from Providence, Rhode Island, to New York. She temporarily closed the school and began directly recruiting new students of color. On March 2, 1833, Garrison published advertisements for new pupils in his newspaper '' The Liberator''. Crandall announced that on the first Monday of April 1833, she would open a school "for the reception of young Ladies and little Misses of color, ... Terms, $25 per quarter, one half paid in advance." Her references including leading abolitionists Arthur Tappan

Arthur Tappan (May 22, 1786 – July 23, 1865) was an American businessman, philanthropist and abolitionist. He was the brother of Ohio Senator Benjamin Tappan and abolitionist Lewis Tappan, and nephew of Harvard Divinity School theologian ...

, May, and Garrison.

As word of the school spread, African-American families began arranging enrollment of their daughters in Crandall's academy. On April 1, 1833, twenty African-American girls from Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Providence, New York, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, and the surrounding areas in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

arrived at Miss Crandall's School for Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color.

Public backlash

Leading the opposition to Crandall's school for black girls was her neighbor Andrew Judson, an attorney and Canterbury's leading politician, having represented it in both the Connecticut House and Senate, and would soon be Connecticut's at-large member of the U.S. House of Representatives. In the national debate that was awkwardly taking place over "what to do" with the freed or soon-to-be-freed slaves, Judson supported "colonization": sending them to (not "back to") Africa (seeAmerican Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

). He said: "We are not merely opposed to the establishment of that school in Canterbury; we mean there shall not be such a school set up anywhere in our State. The colored people can never rise from their menial condition in our country; they ought not to be permitted to rise here. They are an inferior race of beings, and never call or ought to be recognized as the equals of the whites." "He predicted the destruction of the town if Crandall's school for colored children succeeded." Judson was also involved in efforts to capture David Garrison and turn him over to Southerners; there was a $10,000 reward.

In response to the new school, a committee of four prominent white men in the town, Rufus Adams, Daniel Frost Jr., Andrew Harris, and Richard Fenner, attempted to convince Crandall that her school for young women of color would be detrimental to the safety of the white people in the town of Canterbury. Frost claimed that the boarding school would encourage "social equality and intermarriage of whites and blacks." To this, her response was "Moses had a black wife."

At first, citizens of Canterbury protested the school and then held town meetings "to devise and adopt such measures as would effectually avert the nuisance, or speedily abate it." The town response escalated into warnings, threats, and acts of violence against the school. Crandall was faced with great local opposition, and her detractors had no plans to back down.

On May 24, 1833, the Connecticut legislature passed a " Black Law", which prohibited a school from teaching African-American students from outside the state without town permission." Alexander, Elizabeth and Nelson, Marilyn. Miss Crandall's School for Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color", Wordsong, 2007. In July, Crandall was arrested and placed in the county jail for one night—she refused to be bonded out, as she wished the public to know she was being jailed. (A Vermont newspaper reported it under the headline "Shame on Connecticut".) The next day she was released under bond to await her trial.

Under the Black Law, the townspeople refused any amenities to the students or Crandall, closing their shops and meeting houses to them, although they were welcomed at Prudence's Baptist church, in neighboring Plainfield. Stage drivers refused to provide them with transportation, and the town doctors refused to treat them. Townspeople poisoned the school's well—its only water source—with animal feces, and prevented Crandall from obtaining water from other sources. Not only did Crandall and her students receive backlash, but her father was also insulted and threatened by the citizens of Canterbury. Although she faced extreme difficulties, Crandall continued to teach the young women of color which angered the community even further.

Crandall's students also suffered. Ann Eliza Hammond, a 17-year-old student, was arrested; however, with the help of local abolitionist Samuel J. May, she was able to post a bail bond. Some $10,000 was raised through collections and donations.

Judicial proceedings

Arthur Tappan

Arthur Tappan (May 22, 1786 – July 23, 1865) was an American businessman, philanthropist and abolitionist. He was the brother of Ohio Senator Benjamin Tappan and abolitionist Lewis Tappan, and nephew of Harvard Divinity School theologian ...

of New York, a prominent abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, donated $10,000 to hire the best lawyers to defend Crandall throughout her trials. The first opened at the Windham County Court on August 23, 1833. The case challenged the constitutionality of the Connecticut law prohibiting the education of African Americans from outside the state.

The defense argued that African Americans were citizens in other states, so, therefore, there was no reason why they should not be considered as such in Connecticut. Thus, they focused on the deprivation of the rights of African-American students under the United States Constitution. By contrast, the prosecution denied the fact that freed African-Americans were citizens in any state. The county court jury ultimately failed to reach a decision for the cases.

A second trial in Superior Court decided against the school, and the case was taken to the Supreme Court of Errors (now called the Connecticut Supreme Court

The Connecticut Supreme Court, formerly known as the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors, is the highest court in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It consists of a Chief Justice and six Associate Justices. The seven justices sit in Hartford, ac ...

) on appeal in July 1834. The Connecticut high court reversed the decision of the lower court, dismissing the case on July 22 because of a procedural defect. The Black Law prohibited the education of black children from outside of Connecticut unless permission was granted by the local civil authority and town selectmen. But the prosecution's information

Information is an abstract concept that refers to that which has the power to inform. At the most fundamental level information pertains to the interpretation of that which may be sensed. Any natural process that is not completely random ...

that charged Crandall had not alleged that she had established her school without the permission of the civil authority and selectmen of Canterbury. Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the information was fatally defective because the conduct which it alleged did not constitute a crime. The Court did not address the issue of whether the citizenship of free African Americans had to be recognized in every state.

The judicial process had not stopped the operation of the Canterbury boarding school, but the townspeople's vandalism against it increased. The residents of Canterbury were so angry that the court had dismissed the case that vandals set the school on fire in January 1834, but they failed in their attempts to destroy the school."More Than Meets the Eye Historical Archaeology at the Prudence Crandall House." Prudence Crandall Collection, Box 3. ''Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives'', Connecticut College. On September 9, 1834, a group of townspeople broke almost ninety window glass panes using heavy iron bars. For the safety of her students, her family and herself, Prudence Crandall closed her school on September 10, 1834.

Connecticut officially repealed the Black Law in 1838.

Later years

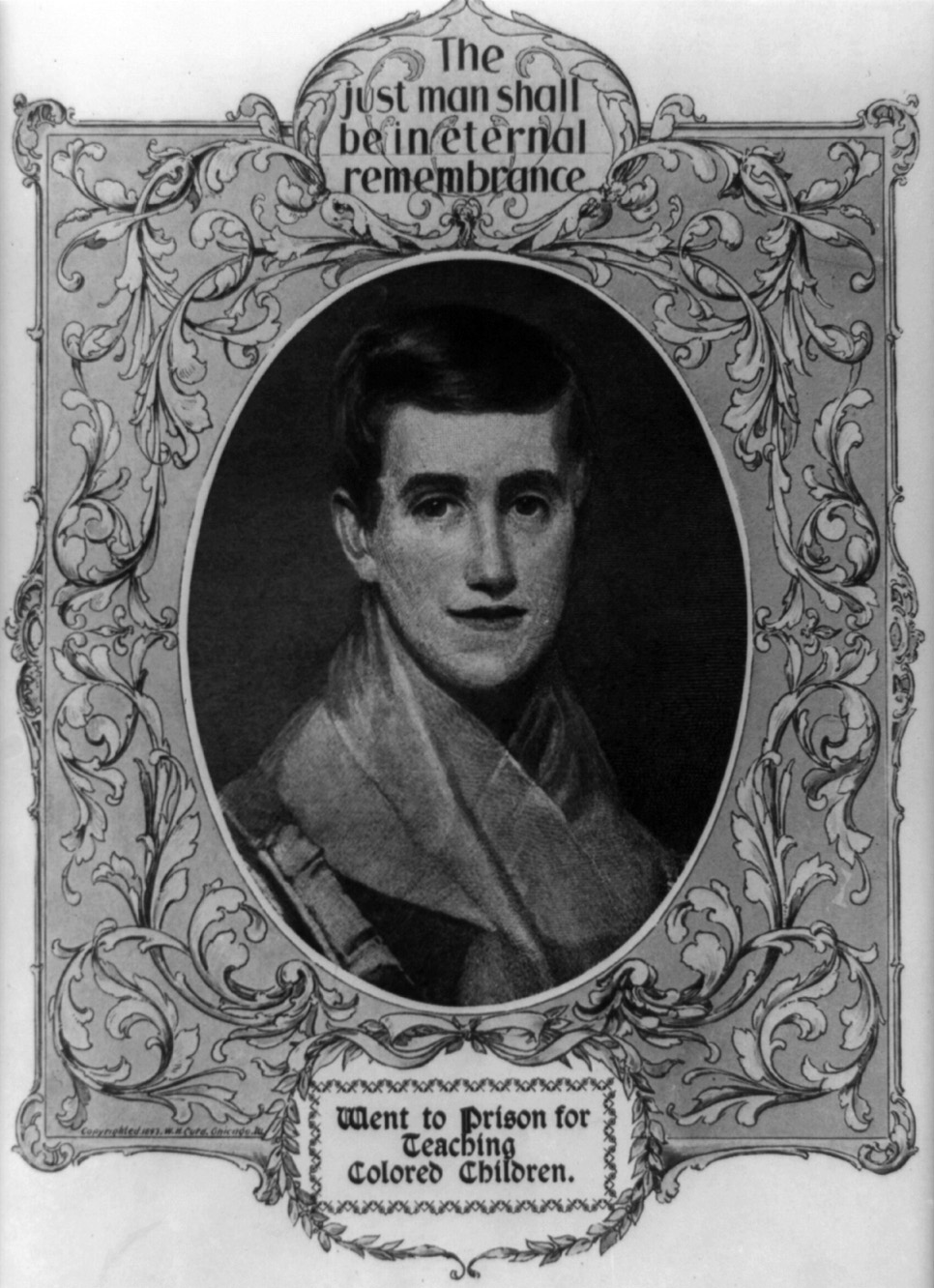

At the suggestion of William Garrison, who raised the money from "various antislavery societies",Francis Alexander

Francis Alexander (February 3, 1800 – March 27, 1880) was an American portrait-painter.

Biography

Alexander was born in Windham county Connecticut in February 1800. Brought up on a farm, he taught himself the use of colors, and in 1820 we ...

painted a portrait of Crandall in April 1834. She had to go to Boston for the sittings, where she "became the center of attention at abolitionist parties and gatherings each evening. The Boston abolitionists honored her as a true heroine of the antislavery cause."

In August 1834, Crandall married the Rev. Calvin Philleo, a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

minister in Canterbury, Connecticut. The couple moved to Massachusetts for a period of time after they fled the town of Canterbury, and they also lived in New York, Rhode Island, and Illinois. Crandall was involved in the women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

movement and ran a school in LaSalle County, Illinois

LaSalle County is located within the Fox Valley and Illinois River Valley regions of the U.S. state of Illinois. As of the 2020 Census, it had a population of 109,658. Its county seat and largest city is Ottawa. LaSalle County is part of the ...

. She separated from Philleo in 1842 after his "deteriorating physical and mental health" led him to be abusive. He died in Illinois in 1874.

After the death of her husband, Crandall relocated with her brother Hezekiah to Elk Falls, Kansas

Elk Falls is a city in Elk County, Kansas, United States, along the Elk River. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 113.

History

The first European-American house was built at Elk Falls in 1870, and a post office was opened ...

, around 1877, and it was there that her brother eventually died in 1881. A visitor of 1886, who described her as "of almost national renown," with "a host of good books in her house", quoted her as follows:

In 1886, the state of Connecticut honored Prudence Crandall with an act by the legislature, prominently supported by the writer Mark Twain, providing her with a $400 annual pension (). Prudence Crandall died in Kansas on January 28, 1890, at the age of 86. She and her brother Hezekiah are buried in Elk Falls Cemetery.

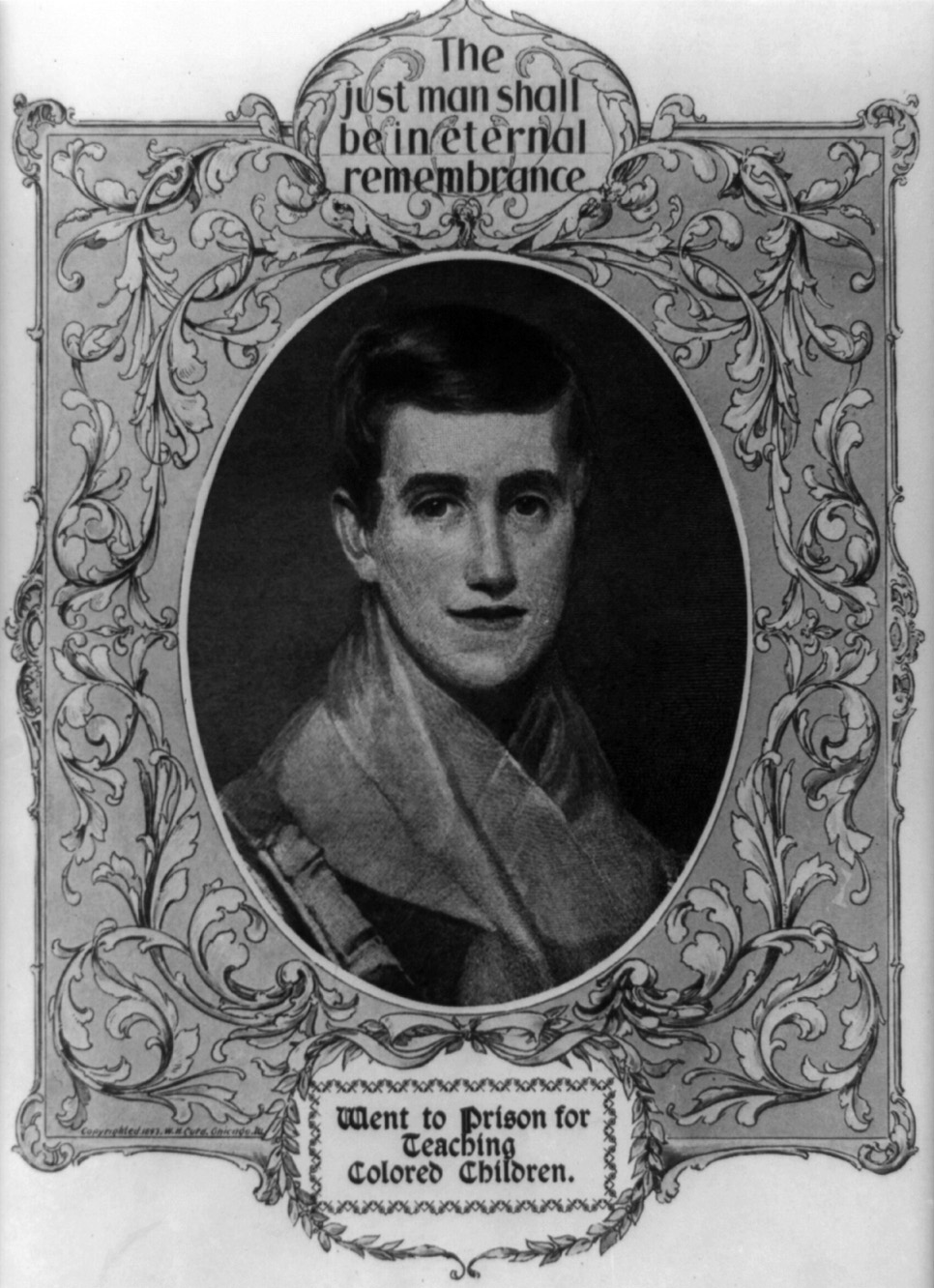

Prudence Crandall's brother Reuben

Prudence's younger brother Reuben was a physician and abotany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

expert. He was no abolitionist and was opposed to Prudence's efforts to educate African-American girls, and told this to her chief enemy Judson, when the latter gave him a ride.

Reuben, who had studied medicine at Yale and practiced for 7 years in Peekskill, New York

Peekskill is a city in northwestern Westchester County, New York, United States, from New York City. Established as a village in 1816, it was incorporated as a city in 1940. It lies on a bay along the east side of the Hudson River, across from ...

, was arrested on August 10, 1835, in Washington, D.C., and charged with sedition and publication of abolitionist literature. He narrowly escaped being lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

. At first denied bail, it was later set so high that he could not meet it, and he was jailed for 8 months before his trial. It was the first trial for sedition in the history of the country, and being in Washington it attracted a large audience, including members of Congress and reporters. Francis Scott Key was the District of Columbia prosecuting attorney. The jury acquitted Reuben of all charges; this was a major public embarrassment for Key and ended his political career. However, Reuben contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

while in jail and died shortly thereafter.Leepson, Marc, ''What so Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, a Life'', (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), pp. 169–172, 181–185

Prudence's sister Almira died in 1837. In 1838 her father Pardon died, followed days later by her sister-in-law Clarissa, who had just given birth.

Legacy

19th century

* An oil portrait of her byFrancis Alexander

Francis Alexander (February 3, 1800 – March 27, 1880) was an American portrait-painter.

Biography

Alexander was born in Windham county Connecticut in February 1800. Brought up on a farm, he taught himself the use of colors, and in 1820 we ...

was commissioned by her supporters in 1834. It is at Cornell University. A printed copy is in the Prudence Crandall Museum.

* The Glasgow Emancipation Society prepared the following piece of "plate

Plate may refer to:

Cooking

* Plate (dishware), a broad, mainly flat vessel commonly used to serve food

* Plates, tableware, dishes or dishware used for setting a table, serving food and dining

* Plate, the content of such a plate (for example: ...

" (silver), which a traveler to the U.S. was going to take to her:

20th century

In the late 20th century, Crandall received renewed attention and honors: * On February 21, 1965, the NBC television seriesProfiles in Courage

''Profiles in Courage'' is a 1956 volume of short biographies describing acts of bravery and integrity by eight United States Senators. The book profiles senators who defied the opinions of their party and constituents to do what they felt was ...

broadcast an episode about her.

*The Prudence Crandall House

The Prudence Crandall Museum is a historic house museum, sometimes called the Elisha Payne House for its previous owner. It is located on the southwest corner of the junction of Connecticut Routes 14 and 169, on the Canterbury, Connecticut vil ...

in Canterbury was acquired by the State of Connecticut in 1969. Now a Connecticut state museum, it was declared a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

in 1991.

* In 1973, the Prudence Crandall Center for Women, since 2003 the Prudence Crandall Center, Inc., was founded in New Britain, Connecticut, to provide shelter for victims of domestic violence.

*Crandall was the subject of a Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

/NBC television movie

A television film, alternatively known as a television movie, made-for-TV film/movie or TV film/movie, is a feature-length film that is produced and originally distributed by or to a television network, in contrast to theatrical films made for ...

entitled ''She Stood Alone'' (1991), in which she was portrayed by actress Mare Winningham

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than four y ...

.

*In 1994 Crandall was inducted into the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame

The Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame (CWHF) recognizes women natives or residents of the U.S. state of Connecticut for their significant achievements or statewide contributions.

The CWHF had its beginnings in 1993 when a group of volunteers partn ...

.

*In 1995, the Connecticut General Assembly designated Prudence Crandall as the state's official heroine.

*The Prudence Crandall Elementary School in Enfield, Connecticut

Enfield is a town in Hartford County, Connecticut, United States, first settled by John and Robert Pease of Salem, Massachusetts Bay Colony. The population was 42,141 at the 2020 census. It is bordered by Longmeadow, Massachusetts, and East Long ...

, opened in 1966.

* In 2001 Crandall was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame.

*In 2008, a statue of Crandall and a pupil was erected in the Connecticut state capital.

Historical marker

The following marker is at Osage Street andU.S. Route 160

U.S. Route 160 (US 160) is a 1,465 mile (2,358 km) long east–west United States highway in the Midwestern and Western United States. The western terminus of the route is at US 89 five miles (8 km) west of Tuba City, Arizo ...

, Elk Falls, Kansas

Elk Falls is a city in Elk County, Kansas, United States, along the Elk River. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 113.

History

The first European-American house was built at Elk Falls in 1870, and a post office was opened ...

:

Archival material

The Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives, atConnecticut College

Connecticut College (Conn College or Conn) is a private liberal arts college in New London, Connecticut. It is a residential, four-year undergraduate institution with nearly all of its approximately 1,815 students living on campus. The college w ...

, in New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decade ...

, has a Prudence Crandall Collection. It contains "23 letters and one manuscript of poems by Crandall, including three letters to the abolitionist Simeon Jocelyn Simeon Jocelyn (1799-1879) was a white pastor, abolitionist, and social activist for African-American civil rights and educational opportunities in New Haven, Connecticut, during the 19th century. He is known for his attempt to establish America's f ...

detailing the opposition to her school. Most of the remaining letters are to her husband, Calvin Philleo. There are also nearly three dozen manuscripts of correspondence and business records of Philleo. The remainder of the collection consists of photographs of Crandall, her family members, and their places of residence and Helen Sellers' research materials and correspondence related to her biography." The Lear Center has also posted a guide to other archival material of or relating to Crandall.

Correspondence with William Garrison is in his papers in the Boston Public Library

The Boston Public Library is a municipal public library system in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, founded in 1848. The Boston Public Library is also the Library for the Commonwealth (formerly ''library of last recourse'') of the Commonwea ...

.

References

Further reading

* * * * *External links

Jennifer Rycenga gives a talk on Prudence Crandall, 2018

April 14, 2018, Otis Library, Norwich, Connecticut. Rycenga has published an article on Crandall (reference above) and is at work on a biography.

''"From Canterbury to Little Rock: The Struggle for Educational Equality for African Americans"'', a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

*

"Hezekiah Crandall"

(sister), Find a Grave. * Find a Grave {{DEFAULTSORT:Crandall, Prudence 1803 births 1890 deaths People from Hopkinton, Rhode Island American Quakers Activists for African-American civil rights American educators School desegregation pioneers Symbols of Connecticut Education in Connecticut People from Canterbury, Connecticut People from Washington County, Rhode Island American suffragists African-American history of Connecticut African Americans and education Moses Brown School alumni Prudence Crandall Women civil rights activists American school principals Founders of schools in the United States