Protestant ethic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Protestant work ethic, also known as the Calvinist work ethic or the Puritan work ethic, is a

Pastor John Starke writes that the Protestant work ethic "multiplied myths about Protestantism, Calvinism, vocation, and capitalism. To this day, many believe Protestants work hard so as to build evidence for salvation."

Some support exists that the Protestant work ethic may be so ingrained in American culture that when it appears people may not recognize it. Due to the history of Protestantism in the United States, it may be difficult to separate the successes of the country from the ethic that may have significantly contributed to propelling it.

Pastor John Starke writes that the Protestant work ethic "multiplied myths about Protestantism, Calvinism, vocation, and capitalism. To this day, many believe Protestants work hard so as to build evidence for salvation."

Some support exists that the Protestant work ethic may be so ingrained in American culture that when it appears people may not recognize it. Due to the history of Protestantism in the United States, it may be difficult to separate the successes of the country from the ethic that may have significantly contributed to propelling it.

* * Robert Green (disambiguation), Robert Green, editor. ''The Weber Thesis Controversy''. D.C. Heath, 1973, covers some of the criticism of Weber's theory. * * Haller, William. "Milton and the Protestant Ethic." ''Journal of British Studies'' 1.1 (1961): 52–57 ww.jstor.org/stable/175098 online * *

work ethic

Work ethic is a belief that work and diligence have a moral benefit and an inherent ability, virtue or value to strengthen character and individual abilities. Desire or determination to work serves as the foundation for values centered on the i ...

concept in sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

, economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, and history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

. It emphasizes that a person's subscription to the values espoused by the Protestant faith, particularly Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

, result in diligence

Diligence—carefulness and persistent effort or work—is listed as one of the seven Seven virtues#Seven capital virtues, capital virtues. It can be indicative of a work ethic, the belief that work is good in itself.

: "There is a perennial ...

, discipline

Discipline is the self-control that is gained by requiring that rules or orders be obeyed, and the ability to keep working at something that is difficult. Disciplinarians believe that such self-control is of the utmost importance and enforce a ...

, and frugality

Frugality is the quality of being frugal, sparing, thrifty, prudent, or economical in the consumption of resources such as food, time or money, and avoiding waste, lavishness or extravagance.

In behavioral science, frugality has been defined as ...

.

The phrase was initially coined in 1905 by sociologist Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

in his book ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'' () is a book written by Max Weber, a German sociologist, economist, and politician. First written as a series of essays, the original German text was composed in 1904 and 1905, and was trans ...

''. Weber asserted that Protestant ethics and values, along with the Calvinist doctrines of asceticism

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing Spirituality, spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world ...

and predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby Go ...

, enabled the rise and spread of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

. Just as priests and caring professionals are deemed to have a vocation

A vocation () is an Work (human activity), occupation to which a person is especially drawn or for which they are suited, trained or qualified. Though now often used in non-religious contexts, the meanings of the term originated in Christianity.

...

(or "calling" from God) for their work, according to the Protestant work ethic the "lowly" workman also has a noble vocation which he can fulfill through dedication to his work.

Weber's book is one of the most influential and cited in sociology, although the thesis presented has been controversial since its release. In opposition to Weber, historians such as Fernand Braudel

Fernand Paul Achille Braudel (; 24 August 1902 – 27 November 1985) was a French historian. His scholarship focused on three main projects: ''The Mediterranean'' (1923–49, then 1949–66), ''Civilization and Capitalism'' (1955–79), and the un ...

and Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton, (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History (Oxford), Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Rope ...

assert that the Protestant work ethic did not create capitalism and that capitalism developed in pre-Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

Catholic communities. Historian Laurence R. Iannaccone has written that "the most noteworthy feature of the Protestant Ethic thesis is its absence of empirical support."

The concept is often credited with helping to define the self-view of societies of Northern, Central and Northwestern Europe

Northwestern Europe, or Northwest Europe, is a loosely defined subregion of Europe, overlapping Northern and Western Europe. The term is used in geographic, history, and military contexts.

Geographic definitions

Geographically, Northwestern ...

as well as the United States.

Weber's theory

Following a study trip to America, Weber developed his theory of the Protestant Ethic, which included more considerations than attitude to work. Those with the ethic believed that good fortune (e.g. from hard work) is a vindication of God in this life: a ''theodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

of fortune''; this supported religious and social actions that proved their right to possess even greater wealth. In contrast, those without the ethic instead emphasized that God will be vindicated by granting wealth and happiness in the next life: a ''theodicy of misfortune''. These beliefs guided expectations, behaviour and culture, etc.

Basis in Protestant theology

According to the theory, Protestants, beginning withMartin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

, conceptualized worldly work as a duty which benefits both the individual and society as a whole. Thus, the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

idea of good works

In Christian theology, good works, or simply works, are a person's exterior actions, deeds, and behaviors that align with certain moral teachings, emphasizing compassion, Charity (Christian virtue), charity, kindness and adherence to biblical pri ...

was transformed for Protestants into an obligation to consistently work diligently as a sign of grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uni ...

. Whereas Catholicism teaches that good works are required of Catholics as a necessary manifestation of the faith they received, and that faith apart from works is dead and barren, the Calvinist theologians taught that only those who were predestined to be saved would be saved.

For Protestants, salvation is a gift from God; this is the Protestant distinction of ''sola gratia

''Sola gratia'', meaning by grace alone, is one of the five ''solae'' and consists in the belief that salvation comes by divine grace or "unmerited favor" only, not as something earned or deserved by the sinner. It is a Christian theologi ...

''. In light of salvation being a gift of grace, Protestants viewed work as stewardship given to them. Thus Protestants were not working in order to achieve salvation but viewed work as the means by which they could be a blessing to others. Hard work and frugality were thought to be two important applications of being a steward of what God had given them. Protestants were thus attracted to these qualities and strove to reach them.

There are many specific theological examples in the Bible used to support a work ethic. Old Testament examples abound, such as God's command in Exodus 20:8–10 to "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God." Another passage from the Book of Proverbs in the Old Testament provides an example: "A little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to rest, and poverty will come upon you like a robber, and want like an armed man."

The New Testament also provides many examples, such as the Parable of the Ten Minas in the Book of Luke.

The Apostle Paul in 2 Thessalonians said "If anyone is not willing to work, let him not eat."

American political history

In 1607, the first English settlement in America was established at Jamestown, led by John Smith. He trained the first English settlers to work at farming and fishing. These settlers were ill-equipped to survive in the English settlements in the early 1600s and were on the precipice of dying. John Smith emphasized the Protestant work ethic and helped propagate it by stating "He that will not work, shall not eat" which is a direct reference to 2 Thessalonians 3:10. This policy is credited with helping the early colony survive and thrive in its relatively harsh environment. WriterFrank Chodorov

Frank Chodorov (February 15, 1887 – December 28, 1966) was an American intellectual, author, and member of the Old Right, a group of classically liberal thinkers who were non-interventionist in foreign policy and opposed to both the America ...

argued that the Protestant ethic was long considered indispensable for American political figures:

Others have connected the concept of a Protestant work ethic to racist ideals. Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

activist Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

said:

Support

Late 20th century works by Lawrence Harrison, Samuel P. Huntington, and David Landes revitalized interest in Weber's thesis. In a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' article, published on June 8, 2003, Niall Ferguson

Sir Niall Campbell Ferguson, ( ; born 18 April 1964)Biography

Niall Ferguson

claimed, using data from the Niall Ferguson

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; , OCDE) is an international organization, intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and international trade, wor ...

(OECD), that "the experience of Western Europe in the past quarter-century offers an unexpected confirmation of the Protestant ethic", that the reason that people in modern Protestant Western European nations actually work fewer hours on average than in the Catholic ones or in the United States is due to a decline in active Protestantism.

Individuals

There are studies of the existence and impact of the so-called Protestant Ethic on individuals. A study at theUniversity of Groningen

The University of Groningen (abbreviated as UG; , abbreviated as RUG) is a Public university#Continental Europe, public research university of more than 30,000 students in the city of Groningen (city), Groningen, Netherlands. Founded in 1614, th ...

shows that unemployed Protestants fare much worse than the general population psychologically.

United States

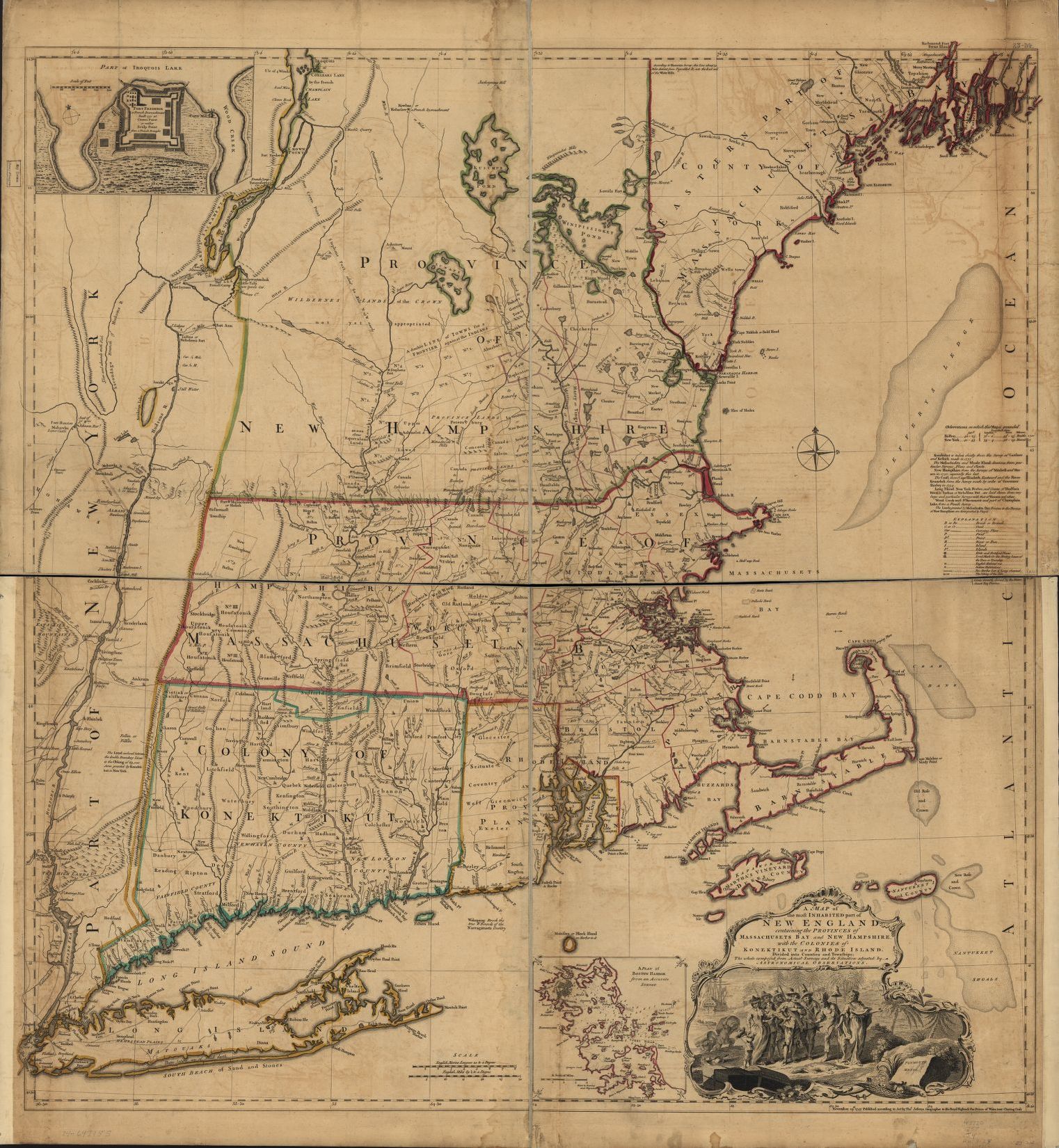

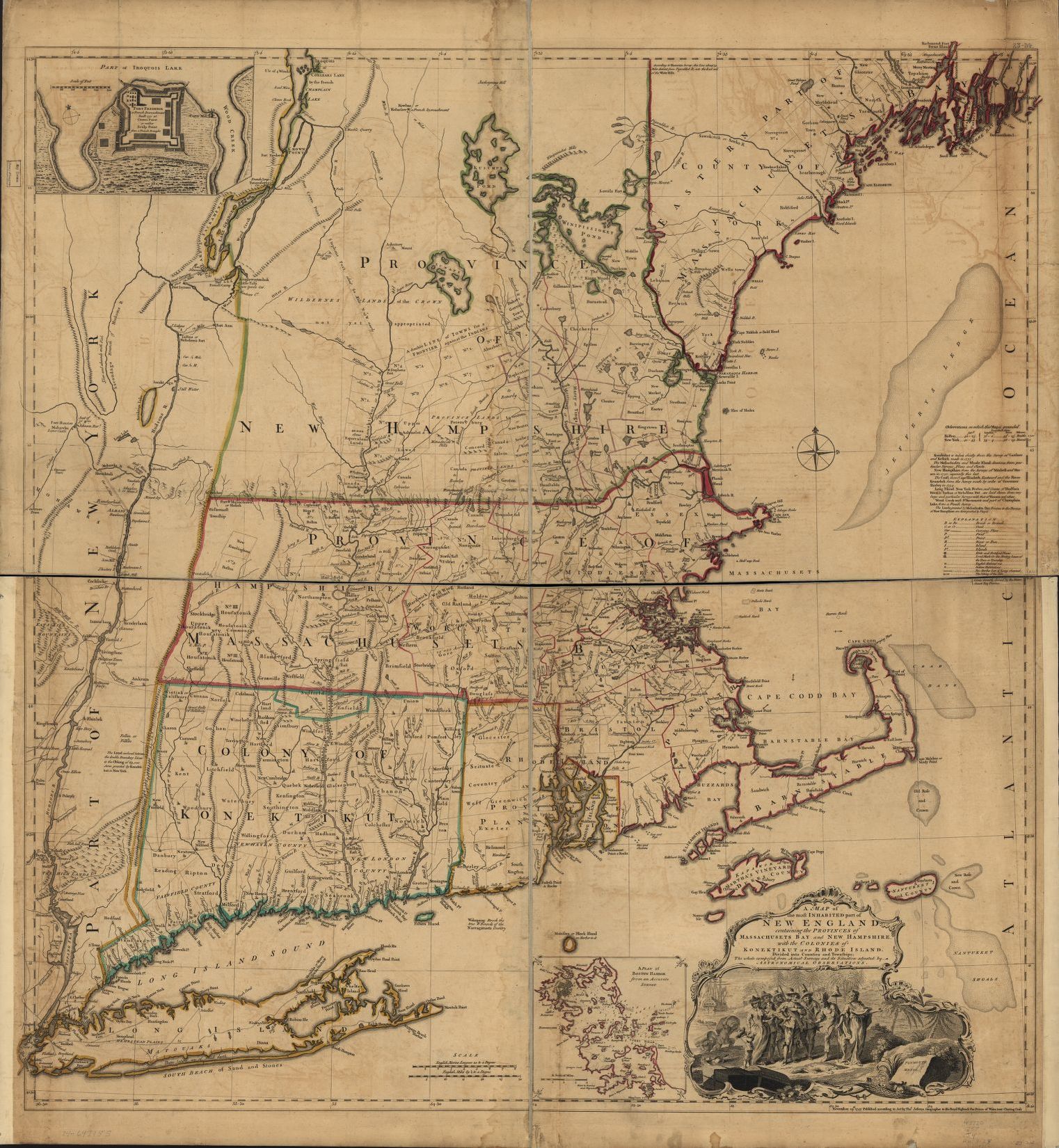

The original New England Colonies in 1677 were mostly Protestant in origin and exhibited industriousness and respect for laws. Pastor John Starke writes that the Protestant work ethic "multiplied myths about Protestantism, Calvinism, vocation, and capitalism. To this day, many believe Protestants work hard so as to build evidence for salvation."

Some support exists that the Protestant work ethic may be so ingrained in American culture that when it appears people may not recognize it. Due to the history of Protestantism in the United States, it may be difficult to separate the successes of the country from the ethic that may have significantly contributed to propelling it.

Pastor John Starke writes that the Protestant work ethic "multiplied myths about Protestantism, Calvinism, vocation, and capitalism. To this day, many believe Protestants work hard so as to build evidence for salvation."

Some support exists that the Protestant work ethic may be so ingrained in American culture that when it appears people may not recognize it. Due to the history of Protestantism in the United States, it may be difficult to separate the successes of the country from the ethic that may have significantly contributed to propelling it.

Contrast with prosperity theology ethic

Tshilidzi Marwala

Tshilidzi Marwala (born 28 July 1971) is a South African artificial intelligence engineer, a computer scientist, a mechanical engineer and a university administrator. He is currently Rector (academia), Rector of the United Nations University ...

asserted in 2020 that the principles of Protestant ethic are important for development in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and that they should be secularized and used as an alternative to the ethic of Prosperity Christianity, which advocates miracles as a basis of development.

In a recent journal article, Benjamin Kirby agrees that this influence of prosperity theology, particularly within neo-Pentecostal movements, complicates any attempt to draw parallels between, first, the relationship between contemporary Pentecostalism and neoliberal

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pej ...

capitalism, and second, the relationship between Calvinistic asceticism and modern capitalism that interested Weber. Nevertheless, Kirby emphasises the enduring relevance of Weber's analysis: he proposes a "new elective affinity" between contemporary Pentecostalism and neoliberal capitalism, suggesting that neo-Pentecostal churches may act as vehicles for embedding neoliberal economic processes, for instance by encouraging practitioners to become entrepreneurial, responsibilised citizens.

Criticism

Historicity

Austrian political economistJoseph Schumpeter

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (; February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950) was an Austrian political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at Harvard Unive ...

argued that capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

began in Italy in the 14th century, not in the Protestant areas of Europe.

Danish macroeconomist Thomas Barnebeck Andersen ''et al.'' found that the location of monasteries of the Catholic Order of Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

s, and specifically their density, highly correlated to this work ethic in later centuries; ninety percent of these monasteries were founded before the year 1300 AD. Economist Joseph Henrich found that this correlation extends right up to the twenty-first century.

Other factors that further developed the European market economy included the strengthening of property right

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership), is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely and is typicall ...

s and lowering of transaction cost

In economics, a transaction cost is a cost incurred when making an economic trade when participating in a market.

The idea that transactions form the basis of economic thinking was introduced by the institutional economist John R. Commons in 1 ...

s with the decline and monetization of feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

, and the increase in real wage

A wage is payment made by an employer to an employee for work (human activity), work done in a specific period of time. Some examples of wage payments include wiktionary:compensatory, compensatory payments such as ''minimum wage'', ''prevailin ...

s following the epidemics of bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

.

Social scientist Rodney Stark commented that "during their critical period of economic development, these northern centers of capitalism were Catholic, not Protestant", with the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

still far off in the future. Furthermore, he also highlighted the conclusions of other historians, noting that, compared to Catholics, Protestants were "not more likely to hold the high-status capitalist positions", that Catholic Europe did not lag in its industrial development compared to Protestant areas, and that even Weber wrote that "fully developed capitalism had appeared in Europe" long before the Reformation. As British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton, (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History (Oxford), Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Rope ...

stated, the concept that "large-scale industrial capitalism was ideologically impossible before the Reformation is exploded by the simple fact that it existed".

French historian Fernand Braudel

Fernand Paul Achille Braudel (; 24 August 1902 – 27 November 1985) was a French historian. His scholarship focused on three main projects: ''The Mediterranean'' (1923–49, then 1949–66), ''Civilization and Capitalism'' (1955–79), and the un ...

wrote that "all historians" opposed the "tenuous theory" of Protestant ethic, despite not being able to entirely quash the theory "once and for all". Braudel continues to remark that the "northern countries took over the place that earlier had been so long and brilliantly been occupied by the old capitalist centers of the Mediterranean. They invented nothing, either in technology or business management".

Historian Laurence R. Iannaccone has written that "Ironically, the most noteworthy feature of the Protestant Ethic thesis is its absence of empirical support", citing the work of Swedish economic historian Kurt Samuelsson that "economic progress was uncorrelated with religion, or was temporally incompatible with Weber's thesis, or actually reversed the pattern claimed by Weber."

German economists Sascha Becker and Ludger Wößmann have posited an alternate theory, claiming that the literacy gap between Protestants (as a result of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

) and Catholics was sufficient explanation for the economic gaps, and that the "results hold when we exploit the initial concentric dispersion of the Reformation to use distance to Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is the fourth-largest town in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, in the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. It is situated on the River Elbe, north of Leipzig and south-west of the reunified German ...

as an instrument for Protestantism". However, they also note that, between Luther (1500) and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), the limited data available has meant that the period in question is regarded as a "black box" and that only "some cursory discussion and analysis" is possible.

Modern effect

A 2021 study argues that the values represented by the Protestant ethic as developed by Max Weber are not exclusively related to Protestantism but to the modernization phase of economic development. Weber observed this phase of development in areas dominated by Protestants at the time of his observations. From these observations, he concludes that a worldly asceticism consisting of a preference for work and a sober life are associated with Protestantism. However Dutch management economists Annemiek Schilpzand and Eelke de Jong argue that this value pattern is associated with the modernization phase of a region's economic development and thus, in principle, can be found for any religion or for non-religious persons. A 2013 study of 44 European countries found that religious heritage of countries explains half of the between-country variation in Europe in Work Ethic, more than modernity, while factors such as income, education, religion and (in another study) secularization explain relatively little. However, the study showed that Protestant heritage was actually the least correlated with a strong work ethic, with Muslim, then Orthodox, then Catholic heritages being the strongest. A 2009 study of 32 mainly developed countries found no difference in ''work ethic'' between Catholics and Protestants, after correcting for demographic and country effects; however, it found substantial support for a ''social ethic'' effect due to e.g. the Catholic attention to production within the family and to personal contacts: "Protestant values are shown to shape a type of individual who exerts greater effort in mutual social control, supports institutions more and more critically, is less bound to close circles of family and friends, and also holds more homogenous values.… (which ultimately works) in favour of anonymous markets, as they facilitate legal enforcement and impersonal exchange." A similar result is in the 2003 analysis of Western Europe by Riis."In modern Europe, the two main religious groups do not differ much in their work ethics, economic individualism, or emphasis on wealth, though there is some indication of differences with respect to cultural individualism."See also

* Achievement ideology * Anglo-Saxon economy * Critical responses to Weber *Critique of work

Critique of work or critique of labour is the critique of, or wish to abolish, work ''as such'', and to critique what the critics of works deem wage slavery.

Critique of work can be existential, and focus on how labour can be and/or feel meani ...

*

* Imperial German influence on Republican Chile

*Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

*Laziness

Laziness (also known as indolence or sloth) is emotional disinclination to activity or exertion despite having the ability to act or to

exert oneself. It is often used as a pejorative; terms for a person seen to be lazy

include " couch potato" ...

* Merton thesis

* Pray and work

* Predestination in Calvinism

*

* Prussian virtues

* Refusal of work

* Right to sit

* Sloth (deadly sin)

*Underclass

The underclass is the segment of the population that occupies the lowest possible position in a social class, class hierarchy, below the core body of the working class. This group is usually considered cut off from the rest of the society.

The g ...

References

Further reading

* * Sascha O. Becker and Ludger Wossmann. "Was Weber Wrong? A Human Capital Theory of Protestant Economics History". Munich Discussion Paper No. 2007-7, January 22, 2007* * Robert Green (disambiguation), Robert Green, editor. ''The Weber Thesis Controversy''. D.C. Heath, 1973, covers some of the criticism of Weber's theory. * * Haller, William. "Milton and the Protestant Ethic." ''Journal of British Studies'' 1.1 (1961): 52–57 ww.jstor.org/stable/175098 online * *

Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

. ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'' () is a book written by Max Weber, a German sociologist, economist, and politician. First written as a series of essays, the original German text was composed in 1904 and 1905, and was trans ...

''. Charles Scribner's sons, 1959.

*

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Protestant Work EthicWork ethic

Work ethic is a belief that work and diligence have a moral benefit and an inherent ability, virtue or value to strengthen character and individual abilities. Desire or determination to work serves as the foundation for values centered on the i ...

Max Weber

Sociological theories

Economy and Christianity

Christian ethics

Work