Principality of North Wales on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Principality of Wales ( cy, Tywysogaeth Cymru) was originally the territory of the native Welsh princes of the

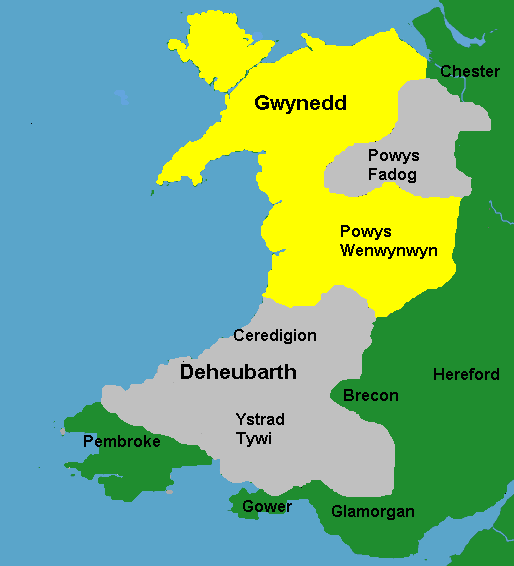

By 1200 Llywelyn Fawr (the Great) ap Iorwerth ruled over all of Gwynedd, with England endorsing all of Llywelyn's holdings that year. England's endorsement was part of a larger strategy of reducing the influence of Powys Wenwynwyn, as King John had given William de Breos licence in 1200 to "seize as much as he could" from the native Welsh. However, de Breos was in disgrace by 1208, and Llywelyn seized both Powys Wenwynwyn and northern Ceredigon.

In his expansion, the Prince was careful not to antagonise King John, his father-in-law. Llywelyn had married

By 1200 Llywelyn Fawr (the Great) ap Iorwerth ruled over all of Gwynedd, with England endorsing all of Llywelyn's holdings that year. England's endorsement was part of a larger strategy of reducing the influence of Powys Wenwynwyn, as King John had given William de Breos licence in 1200 to "seize as much as he could" from the native Welsh. However, de Breos was in disgrace by 1208, and Llywelyn seized both Powys Wenwynwyn and northern Ceredigon.

In his expansion, the Prince was careful not to antagonise King John, his father-in-law. Llywelyn had married  Early in 1212 Llywelyn had regained the Perfeddwlad and burned the castle at Aberystwyth. Llywelyn's revolt caused John to postpone his invasion of France, and Philip Augustus, the King of France, was so moved as to contact Llywelyn and propose that they ally against the English king, King John ordered the execution by hanging of his Welsh hostages, the sons of many of Llywelyn's supporters, Llywelyn I was the first prince to receive the fealty of other Welsh lords at the 1216 Council of Aberdyfi, thus becoming the ''de facto'' Prince of Wales and giving substance to the Aberffraw claims.

Early in 1212 Llywelyn had regained the Perfeddwlad and burned the castle at Aberystwyth. Llywelyn's revolt caused John to postpone his invasion of France, and Philip Augustus, the King of France, was so moved as to contact Llywelyn and propose that they ally against the English king, King John ordered the execution by hanging of his Welsh hostages, the sons of many of Llywelyn's supporters, Llywelyn I was the first prince to receive the fealty of other Welsh lords at the 1216 Council of Aberdyfi, thus becoming the ''de facto'' Prince of Wales and giving substance to the Aberffraw claims.

After achieving victory over his brothers, Llywelyn went on to reconquer the areas of Gwynedd occupied by England (the Perfeddwlad and others). His alliance with

After achieving victory over his brothers, Llywelyn went on to reconquer the areas of Gwynedd occupied by England (the Perfeddwlad and others). His alliance with

The political maturation of the principality's government fostered a more defined relationship between prince and the people. Emphasis was placed on the territorial integrity of the principality, with the prince as lord of all the land, and other Welsh lords swearing fealty to the prince directly, a distinction with which the Prince of Wales paid yearly tribute to the King of England. By treaty the principality was obliged to pay the kingdom large annual sums. Between 1267 and 1272 Wales made a total payment of £11,500, "proof of a growing money economy... and testimony of the effectiveness of the principality's financial administration," wrote historian Dr. John Davies. Additionally, modifications and amendments to the Law Codes of Hywel Dda encouraged the decline of the galanas (blood-fine) and the use of the jury system. The Aberffraw dynasty maintained vigorous diplomatic and domestic policies; and patronized the Church in Wales, particularly that of the

The political maturation of the principality's government fostered a more defined relationship between prince and the people. Emphasis was placed on the territorial integrity of the principality, with the prince as lord of all the land, and other Welsh lords swearing fealty to the prince directly, a distinction with which the Prince of Wales paid yearly tribute to the King of England. By treaty the principality was obliged to pay the kingdom large annual sums. Between 1267 and 1272 Wales made a total payment of £11,500, "proof of a growing money economy... and testimony of the effectiveness of the principality's financial administration," wrote historian Dr. John Davies. Additionally, modifications and amendments to the Law Codes of Hywel Dda encouraged the decline of the galanas (blood-fine) and the use of the jury system. The Aberffraw dynasty maintained vigorous diplomatic and domestic policies; and patronized the Church in Wales, particularly that of the

A more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed for the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature, law, and religion. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffydd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffydd I as reforming the orders of bards and musicians; Welsh literature demonstrated "vigor and a sense of commitment" as new ideas reached Wales, even in "the wake of the invaders", according to historian John Davies. Contacts with continental Europe "sharpened Welsh pride", wrote Davies in his ''History of Wales''.

A more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed for the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature, law, and religion. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffydd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffydd I as reforming the orders of bards and musicians; Welsh literature demonstrated "vigor and a sense of commitment" as new ideas reached Wales, even in "the wake of the invaders", according to historian John Davies. Contacts with continental Europe "sharpened Welsh pride", wrote Davies in his ''History of Wales''.

The remainder of the principality comprised lands which Edward I had granted to supporters shortly after the completion of the conquest in 1284, and which, in practice, became

The remainder of the principality comprised lands which Edward I had granted to supporters shortly after the completion of the conquest in 1284, and which, in practice, became

The following received the title while the Principality was in existence:

*

The following received the title while the Principality was in existence:

*

Owain Glyndŵr was crowned at

Owain Glyndŵr was crowned at

House of Aberffraw

The Royal House of Aberffraw was a cadet branch of the Kingdom of Gwynedd originating from the sons of Rhodri the Great in the 9th century. Establishing the Royal court ( cy, Llys) of the Aberffraw Commote would begin a new location from which t ...

from 1216 to 1283, encompassing two-thirds of modern Wales during its height of 1267–1277. Following the conquest of Wales by Edward I of England

The conquest of Wales by Edward I took place between 1277 and 1283. It is sometimes referred to as the Edwardian Conquest of Wales,Examples of historians using the term include Professor J. E. Lloyd, regarded as the founder of the modern academi ...

of 1277 to 1283, those parts of Wales retained under the direct control of the English crown, principally in the north and west of the country, were re-constituted as a new Principality of Wales and ruled either by the monarch or the monarch's heir though not formally incorporated into the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, ...

. This was ultimately accomplished with the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542

The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 ( cy, Y Deddfau Cyfreithiau yng Nghymru 1535 a 1542) were Acts of the Parliament of England, and were the parliamentary measures by which Wales was annexed to the Kingdom of England. Moreover, the legal sys ...

when the Principality ceased to exist as a separate entity.

The Principality was formally founded in 1216 by native Welshman and King of Gwynedd, Llywelyn the Great who gathered other leaders of ''pura Wallia'' at the Council of Aberdyfi. The agreement was later recognised by the 1218 Treaty of Worcester

Llywelyn the Great ( cy, Llywelyn Fawr, ; full name Llywelyn mab Iorwerth; c. 117311 April 1240) was a King of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually " Prince of the Welsh" (in 1228) and "Prince of Wales" (in 1240). By a combination of war and d ...

between Llywelyn the Great of Wales and Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

. The treaty gave substance to the political reality of 13th-century Wales and England, and the relationship of the former with the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

. The principality retained a great degree of autonomy, characterized by a separate legal jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

based on the well-established laws of ''Cyfraith Hywel

''Cyfraith Hywel'' (; ''Laws of Hywel''), also known as Welsh law ( la, Leges Walliæ), was the system of law practised in medieval Wales before its final conquest by England. Subsequently, the Welsh law's criminal codes were superseded by ...

'', and by the increasingly sophisticated court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in acco ...

of the House of Aberffraw

The Royal House of Aberffraw was a cadet branch of the Kingdom of Gwynedd originating from the sons of Rhodri the Great in the 9th century. Establishing the Royal court ( cy, Llys) of the Aberffraw Commote would begin a new location from which t ...

. Although it owed fealty to the Angevin king of England, the principality was ''de facto'' independent, with a similar status in the empire to the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

. Its existence has been seen as proof that all the elements necessary for the growth of Welsh statehood were in place.

The period of ''de facto'' independence ended with Edward I's conquest of the principality between 1277 and 1283. Under the Statute of Rhuddlan

The Statute of Rhuddlan (12 Edw 1 cc.1–14; cy, Statud Rhuddlan ), also known as the Statutes of Wales ( la, Statuta Valliae) or as the Statute of Wales ( la, Statutum Valliae, links=no), provided the constitutional basis for the government of ...

, the principality lost its independence and became effectively an annexed territory of the English crown. From 1301, the crown's lands in north and west Wales formed part of the appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much o ...

of England's heir apparent, with the title "Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

". On accession of the prince to the English throne, the lands and title became merged with the Crown again. On two occasions Welsh claimants to the title rose up in rebellion during this period, although neither ultimately succeeded.

Since the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, which formally incorporated all of Wales within the Kingdom of England, there has been no geographical or constitutional basis for describing any of the territory of Wales as a principality, although the term has occasionally been used in an informal sense to describe the country, and in relation to the honorary title of Prince of Wales.

The Pre-Conquest Principality

The Principality of Wales was created in 1216 at the Council of Aberdyfi, when it was agreed between Llywelyn the Great and the other sovereign princes among the Welsh that he was the paramount ruler amongst them, and they would pay homage to him. Later he obtained recognition, at least in part, of this agreement from the King of England, who agreed that Llywelyn's heirs and successors would enjoy the title "Prince of Wales" but with certain limitations to his realm and other conditions, including homage to the King of England as vassal, and adherence to rules regarding a legitimate succession. Llywelyn had been at pains to ensure that his heirs and successors would follow the "approved" (by the Pope at least) system of inheritance which excluded illegitimate sons. In so doing he excluded his elder bastard sonGruffydd ap Llywelyn

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn ( 5 August 1063) was King of Wales from 1055 to 1063. He had previously been King of Gwynedd and Powys in 1039. He was the son of King Llywelyn ap Seisyll and Angharad daughter of Maredudd ab Owain, and the great-gre ...

from the inheritance, a decision which would have later ramifications. In 1240 Llywelyn died and Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

(who succeeded John) promptly invaded large areas of his former realm, usurping them from him. However, the two sides came to peace and Henry honoured at least part of the agreement and bestowed upon Dafydd ap Llywelyn

Dafydd ap Llywelyn (''c.'' March 1212 – 25 February 1246) was Prince of Gwynedd from 1240 to 1246. He was the first ruler in Wales to claim the title Prince of Wales.

Birth and descent

Though birth years of 1208, 1206, and 1215 have ...

the title 'Prince of Wales'. This title would be granted to his successor Llywelyn in 1267 (after a campaign by him to achieve it) and was later claimed by his brother Dafydd and other members of the princely House of Aberffraw

The Royal House of Aberffraw was a cadet branch of the Kingdom of Gwynedd originating from the sons of Rhodri the Great in the 9th century. Establishing the Royal court ( cy, Llys) of the Aberffraw Commote would begin a new location from which t ...

.

Aberffraw Princes

Llywelyn ap Iorwerth 1195–1240

By 1200 Llywelyn Fawr (the Great) ap Iorwerth ruled over all of Gwynedd, with England endorsing all of Llywelyn's holdings that year. England's endorsement was part of a larger strategy of reducing the influence of Powys Wenwynwyn, as King John had given William de Breos licence in 1200 to "seize as much as he could" from the native Welsh. However, de Breos was in disgrace by 1208, and Llywelyn seized both Powys Wenwynwyn and northern Ceredigon.

In his expansion, the Prince was careful not to antagonise King John, his father-in-law. Llywelyn had married

By 1200 Llywelyn Fawr (the Great) ap Iorwerth ruled over all of Gwynedd, with England endorsing all of Llywelyn's holdings that year. England's endorsement was part of a larger strategy of reducing the influence of Powys Wenwynwyn, as King John had given William de Breos licence in 1200 to "seize as much as he could" from the native Welsh. However, de Breos was in disgrace by 1208, and Llywelyn seized both Powys Wenwynwyn and northern Ceredigon.

In his expansion, the Prince was careful not to antagonise King John, his father-in-law. Llywelyn had married Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*:Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

* Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

, King John's illegitimate daughter, in 1204. In 1209 Prince Llywelyn joined King John on his campaign in Scotland. However, by 1211 King John recognised the growing influence of Prince Llywelyn as a threat to English authority in Wales. King John invaded Gwynedd and reached the banks of the Menai, and Llywelyn was forced to cede the Perfeddwlad, and recognize John as his heir presumptive if Llywelyn's marriage to Joan did not produce any legitimate successors. Succession was a complicated matter given that Welsh law recognized children born out of wedlock as equal to those in born in wedlock and sometimes accepted claims through the female line. By then, Llywelyn had several illegitimate children. Many of Llywelyn's Welsh allies had abandoned him during England's invasion of Gwynedd, preferring an overlord far away rather than one nearby. Welsh lords expected an unobtrusive English crown; but King John had a castle built at Aberystwyth, and his direct interference in Powys and the Perfeddwlad caused many of these Welsh lords to rethink their position. Llywelyn capitalised on Welsh resentment against King John, and led a church-sanctioned revolt against him. As King John was an enemy of the church, Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

gave his blessing to Llywelyn's revolt.

Dafydd ap Llywelyn 1240–46

On succeeding his father, Dafydd immediately had to contend with the claims of his half-brother, Gruffudd, to the throne. Having imprisoned Gruffudd, his ambitions were curbed by an invasion of Wales led by Henry III in league with a number of the captive Gruffudd's supporters. In August 1241, Dafydd capitulated and signed the Treaty of Gwerneigron, further restricting his powers. By 1244, however, Gruffudd was dead, and Dafydd seems to have benefited from the backing of many of his brother's erstwhile supporters. He was acknowledged by the Pope asPrince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

for a time, and defeated Henry III in battle in 1245 during the English king's second invasion of Wales. A truce was agreed in the autumn, and Henry withdrew; but Dafydd died unexpectedly in 1246 without issue. His wife, Isabella de Braose, returned to England; she was dead by 1248.

Dafydd married Isabella de Braose in 1231. Their marriage produced no children, and there is no contemporary evidence that Dafydd sired any heirs. According to late genealogical sources collected by Bartrum (1973), Dafydd had two children by an unknown woman (or women), a daughter, Annes, and a son, Llywelyn ap Dafydd, who apparently later became Constable of Rhuddlan and was succeeded in that post by his son Cynwrig ap Llywelyn.

Owain Goch ap Gruffydd 1246–53 (d. 1282)

Following Dafydd's death, Gwynedd was divided between Owain Goch and his younger brother Llywelyn. This situation lasted until 1252 when their younger brotherDafydd ap Gruffudd

Dafydd ap Gruffydd (11 July 1238 – 3 October 1283) was Prince of Wales from 11 December 1282 until his execution on 3 October 1283 on the orders of King Edward I of England. He was the last native Prince of Wales before the conquest of Wa ...

reached his majority. Disagreement about how to further divide the realm led to conflict in 1253 in which Llywelyn was victorious. Owain spent the remainder of his days a prisoner of his brother.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd 1246–82

After achieving victory over his brothers, Llywelyn went on to reconquer the areas of Gwynedd occupied by England (the Perfeddwlad and others). His alliance with

After achieving victory over his brothers, Llywelyn went on to reconquer the areas of Gwynedd occupied by England (the Perfeddwlad and others). His alliance with Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the ...

, in 1265 against King Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

allowed him to reconquer large areas of mid Wales from the English Marcher Lord

A Marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A Marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in ...

s. At the Treaty of Montgomery

The Treaty of Montgomery was an Anglo-Welsh treaty signed on 29 September 1267 in Montgomeryshire by which Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was acknowledged as Prince of Wales by King Henry III of England (r. 1216–1272). It was the only time an English ...

between England and Wales in 1267 Llywelyn was granted the title "Prince of Wales" for his heirs and successors and allowed to keep the lands he had conquered as well as the homage of lesser Welsh princes in return for his own homage to the King of England and payment of a substantial fee. Disputes between him, his brother Dafydd and English lords bordering his own led to renewed conflict with England (now ruled by Edward I) in 1277. Following the Treaty of Aberconwy

The Treaty of Aberconwy was signed on the 10th of November 1277, the treaty was by King Edward I of England and Llewelyn the Last, Prince of Wales, following Edward’s invasion of Llewelyn’s territories earlier that year. The treaty granted p ...

Llywelyn was confined to Gwynedd-uwch-Conwy. He joined a revolt instigated by his brother Dafydd in 1282 in which he died in battle.

Dafydd ap Gruffudd 1282–83

Dafydd assumed his elder brother's title in 1282 and led a brief period of continued resistance against England. He was captured and executed in 1283.Government, administration and law

The political maturation of the principality's government fostered a more defined relationship between prince and the people. Emphasis was placed on the territorial integrity of the principality, with the prince as lord of all the land, and other Welsh lords swearing fealty to the prince directly, a distinction with which the Prince of Wales paid yearly tribute to the King of England. By treaty the principality was obliged to pay the kingdom large annual sums. Between 1267 and 1272 Wales made a total payment of £11,500, "proof of a growing money economy... and testimony of the effectiveness of the principality's financial administration," wrote historian Dr. John Davies. Additionally, modifications and amendments to the Law Codes of Hywel Dda encouraged the decline of the galanas (blood-fine) and the use of the jury system. The Aberffraw dynasty maintained vigorous diplomatic and domestic policies; and patronized the Church in Wales, particularly that of the

The political maturation of the principality's government fostered a more defined relationship between prince and the people. Emphasis was placed on the territorial integrity of the principality, with the prince as lord of all the land, and other Welsh lords swearing fealty to the prince directly, a distinction with which the Prince of Wales paid yearly tribute to the King of England. By treaty the principality was obliged to pay the kingdom large annual sums. Between 1267 and 1272 Wales made a total payment of £11,500, "proof of a growing money economy... and testimony of the effectiveness of the principality's financial administration," wrote historian Dr. John Davies. Additionally, modifications and amendments to the Law Codes of Hywel Dda encouraged the decline of the galanas (blood-fine) and the use of the jury system. The Aberffraw dynasty maintained vigorous diplomatic and domestic policies; and patronized the Church in Wales, particularly that of the Cistercian Order

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Sain ...

.

The princely court

At the end of the twelfth century, beginning of the thirteenth century,Llywelyn ab Iorwerth

Llywelyn the Great ( cy, Llywelyn Fawr, ; full name Llywelyn mab Iorwerth; c. 117311 April 1240) was a King of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually " Prince of the Welsh" (in 1228) and "Prince of Wales" (in 1240). By a combination of war and d ...

(Llywelyn Fawr or Llywelyn the Great), built a royal home at Abergwyngregyn

Abergwyngregyn () is a village and community of historical note in Gwynedd, a county and principal area in Wales. Under its historic name of Aber Garth Celyn it was the seat of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. It lies in the historic county of Caernarf ...

(known as ''Tŷ Hir'', the Long House, in later documents) on the site of the subsequent manor house of Pen y Bryn

A pen is a common writing instrument that applies ink to a surface, usually paper, for writing or drawing. Early pens such as reed pens, quill pens, dip pens and ruling pens held a small amount of ink on a nib or in a small void or cavity ...

. To the east was the newly endowed Cistercian Monastery of Aberconwy; to the west the cathedral city of Bangor. In 1211, King John of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Emp ...

brought an army across the river Conwy, and occupied the royal home for a brief period; his troops went on to burn Bangor. Llywelyn's wife, John's daughter Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*:Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

* Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

, also known as Joanna, negotiated between the two men, and John withdrew. Joan died at Abergwyngregyn in 1237; Dafydd ap Llywelyn died there in 1246; Eleanor de Montfort, Lady of Wales, wife of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

, died there on 19 June 1282, giving birth to a baby, Gwenllian of Wales

Gwenllian of Wales or Gwenllian ferch Llywelyn (June 1282 – 7 June 1337) was the second daughter of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the last native Prince of Wales (). Gwenllian is sometimes confused with Gwenllian ferch Gruffudd, who lived two cent ...

.

Population, culture and society

The 13th-century Principality of Wales encompassed three-quarters of the surface area of modern Wales; "fromAnglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

to Machen

Machen (from Welsh ' "place (of)" + ', a personal name) is a large village three miles east of Caerphilly, south Wales. It is situated in the Caerphilly borough within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire. It neighbours Bedwas and Trethom ...

, from the outskirts of Chester to the outskirts of Cydweli," wrote Davies. By 1271, Prince Llywelyn II could claim a growing population of about 200,000 people, or a little less than three-quarters of the total Welsh population. The population increase was common throughout Europe in the 13th century, but in Wales it was more pronounced. By Llywelyn II's reign as much as 10 percent of the population were town-dwellers. Additionally, "unfree slaves... had long disappeared" from within the territory of the principality, wrote Davies. The increase in men allowed the prince to call on and field a far more substantial army.

A more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed for the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature, law, and religion. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffydd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffydd I as reforming the orders of bards and musicians; Welsh literature demonstrated "vigor and a sense of commitment" as new ideas reached Wales, even in "the wake of the invaders", according to historian John Davies. Contacts with continental Europe "sharpened Welsh pride", wrote Davies in his ''History of Wales''.

A more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed for the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature, law, and religion. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffydd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffydd I as reforming the orders of bards and musicians; Welsh literature demonstrated "vigor and a sense of commitment" as new ideas reached Wales, even in "the wake of the invaders", according to historian John Davies. Contacts with continental Europe "sharpened Welsh pride", wrote Davies in his ''History of Wales''.

Economy and trade

The increase in the Welsh population, especially in the lands of the principality, allowed for a greater diversification of the economy. The Meirionnydd tax rolls give evidence to the thirty-seven various professions present in Meirionnydd directly before the conquest. Of these professions, there were eightgoldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and servicea ...

s, four bards (poets) by trade, 26 shoemaker

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or cobblers (also known as '' cordwainers''). In the 18th century, dozens or even hundreds of masters, journeymen ...

s, a doctor in Cynwyd and a hotel

A hotel is an establishment that provides paid lodging on a short-term basis. Facilities provided inside a hotel room may range from a modest-quality mattress in a small room to large suites with bigger, higher-quality beds, a dresser, a re ...

keeper in Maentwrog

Maentwrog () is a village and community in the Welsh county of Merionethshire (now part of Gwynedd), lying in the Vale of Ffestiniog just below Blaenau Ffestiniog, within the Snowdonia National Park. The River Dwyryd runs alongside the vi ...

, and 28 priests; two of whom were university graduates. Also present were a significant number of fishermen

A fisher or fisherman is someone who captures fish and other animals from a body of water, or gathers shellfish.

Worldwide, there are about 38 million commercial and subsistence fishers and fish farmers. Fishers may be professional or recreati ...

, administrators, professional men and craftsmen.

With the average temperature of Wales a degree or two higher than it is today, more Welsh lands were arable for agriculture, "a crucial bonus for a country like Wales," wrote the historian John Davies. Of significant importance for the principality included more developed trade routes, which allowed for the introduction of new energy sources such as the windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

, the fulling mill

Fulling, also known as felting, tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven or knitted cloth (particularly wool) to elimin ...

and the horse collar

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to whi ...

(which doubled the efficiency of horse-power).

The principality traded cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

, skins, cheese, timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, w ...

, horses, wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

, dogs, hawks, and fleeces, but also flannel

Flannel is a soft woven fabric, of various fineness. Flannel was originally made from carded wool or worsted yarn, but is now often made from either wool, cotton, or synthetic fiber. Flannel is commonly used to make tartan clothing, blankets, ...

(with the growth of fulling mills). Flannel was second only to cattle among the principality's exports. In exchange, the principality imported salt, wine, wheat, and other luxuries from London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. But most importantly for the defence of the principality, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

and specialised weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, ...

ry were also imported. Welsh dependence on foreign imports was a tool that England used to wear down the principality during times of conflict between the two countries.

1284 to 1543: annexed to the English crown

Establishment and governance

Between 1277 and 1283,Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vas ...

conquered the territories of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

and the other last remaining native Welsh princes. The governance and constitutional position of the principality after its conquest was set out in the Statute of Rhuddlan

The Statute of Rhuddlan (12 Edw 1 cc.1–14; cy, Statud Rhuddlan ), also known as the Statutes of Wales ( la, Statuta Valliae) or as the Statute of Wales ( la, Statutum Valliae, links=no), provided the constitutional basis for the government of ...

of 1284. In the words of the Statute, the principality was "annexed and united" to the English crown.

The Principality's administration was overseen by the Prince of Wales's Council comprising between 8 and 15 councillors sitting in London or, later, Ludlow

Ludlow () is a market town in Shropshire, England. The town is significant in the history of the Welsh Marches and in relation to Wales. It is located south of Shrewsbury and north of Hereford, on the A49 road which bypasses the town. The ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

. The Council acted as the Principality's final Court of Appeal. By 1476, the Council, which became known as the Council of Wales and the Marches

The Court of the Council in the Dominion and Principality of Wales, and the Marches of the same, commonly called the Council of Wales and the Marches () or the Council of the Marches, was a regional administrative body based in Ludlow Castle wi ...

, began taking responsibility not only for the Principality itself but its authority was extended over the whole of Wales.

The territory of the principality fell into two distinct areas: the lands under direct royal control and lands which Edward I had distributed by feudal grants.

For lands under royal control, the administration, under the Statute of Rhuddlan, was divided into the two territories: North Wales based at Caernarfon and West Wales based at Carmarthen. The Statute organized the Principality into shire counties. Carmarthenshire

Carmarthenshire ( cy, Sir Gaerfyrddin; or informally ') is a county in the south-west of Wales. The three largest towns are Llanelli, Carmarthen and Ammanford. Carmarthen is the county town and administrative centre. The county is known as ...

and Cardiganshire were administered by the Justiciar of South Wales The Justiciar of South Wales, sometimes referred to as the Justiciar of West Wales was a royal official of the Principality of Wales during the medieval period. He controlled the southern half of the principality.

Background

Justiciar was a title ...

(or "of West Wales") at Carmarthen. In the North, the counties of Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

, Merionethshire

, HQ= Dolgellau

, Government= Merionethshire County Council (1889-1974)

, Origin=

, Status=

, Start= 1284

, End=

, Code= MER

, CodeName= ...

, and Caernarfonshire

, HQ= County Hall, Caernarfon

, Map=

, Image= Flag

, Motto= Cadernid Gwynedd (The strength of Gwynedd)

, year_start=

, Arms= ''Coat of arms of Caerna ...

were created under the control of Justiciar of North Wales

The Justiciar of North Wales was a legal office concerned with the government of the three counties in north-west Wales during the medieval period. Justiciar was a title which had been given to one of the monarch's chief ministers in both England a ...

and a provincial exchequer at Caernarfon, run by the Chamberlain of North Wales, who accounted for the revenues he collected to the Exchequer

In the civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty’s Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's '' current account'' (i.e., money held from taxation and other government revenu ...

at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. Under them were royal officials such as sheriffs, coroners, and bailiffs to collect taxes and administer justice. Another county, Flintshire

, settlement_type = County

, image_skyline =

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, image_shield = Arms of Flint ...

, was created out of the lordships of Tegeingl

Tegeingl, in English Englefield, was a cantref in north-east Wales during the mediaeval period. It was incorporated into Flintshire following Edward I of England's conquest of northern Wales in the 13th century.

Etymology

The region's name was ...

, Hopedale and Maelor Saesneg

English Maelor ( cy, Maelor Saesneg) comprises one half of the Maelor region on the Welsh side of the Wales-England border, being the area of the Maelor east of the River Dee. The region has changed counties several times, previously being part ...

, and was administered with the Palatinate of Cheshire by the Justiciar of Chester.

The remainder of the principality comprised lands which Edward I had granted to supporters shortly after the completion of the conquest in 1284, and which, in practice, became

The remainder of the principality comprised lands which Edward I had granted to supporters shortly after the completion of the conquest in 1284, and which, in practice, became Marcher lordship

A Marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A Marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in ...

s: for example, the lordship of Denbigh

The Lordship of Denbigh was a marcher lordship in North Wales created by Edward I in 1284 and granted to the Earl of Lincoln. It was centred on the borough of Denbigh and Denbigh Castle. The lordship was held successively by several of England's ...

granted to the Earl of Lincoln and the lordship of Powys granted to Owain ap Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, who became Owen de la Pole

Owen de la Pole (c. 1257 – c. 1293), also known as Owain ap Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, was the heir presumptive to the Welsh principality of Powys Wenwynwyn until 1283 when it was abolished by the Parliament of Shrewsbury. He became the 1st Lord o ...

. These lands after 1301 were held as tenants-in-chief

In medieval and early modern Europe, the term ''tenant-in-chief'' (or ''vassal-in-chief'') denoted a person who held his lands under various forms of feudal land tenure directly from the king or territorial prince to whom he did homage, as oppos ...

of the Principality of Wales, rather than from the Crown directly, but were, for all practical purposes, not part of the principality.

Law

The Statute of Rhuddlan also introducedEnglish common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

to the principality, albeit with some local variation. Criminal law became entirely based on common law: the Statute stated that "in thefts, larcenies, burnings, murders, manslaughters and manifest and notorious robberies – we will that they shall use the laws of England". However, Welsh law

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 20 ...

continued to be used in civil cases such as land inheritance, contracts, sureties and similar matters, though with changes, for example illegitimate sons could no longer claim part of the inheritance, which Welsh law had allowed them to do. In 1301, this modified principality was bestowed on the English monarch's heir apparent and thereafter became the territorial endowment of the heir to the throne.

There were few attempts by the English parliament to legislate in Wales and the lands of the Principality remained subject to laws enacted by the king and his council. However, the king was prepared to allow Parliament to legislate in emergencies such as treason or rebellion. An example was the Penal Laws against Wales 1402 enacted to contain the Glyndŵr Rising

The Welsh Revolt (also called the Glyndŵr Rising or Last War of Independence) ( cy, Rhyfel Glyndŵr) or ( cy, Gwrthryfel Glyndŵr) was a Welsh rebellion in Wales led by Owain Glyndŵr against the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ag ...

and which, ''inter alia'', prohibited the Welsh from intermarrying with the English or owning land in England or the Welsh boroughs. Some Welshman who were loyal to the Principality successfully petitioned for exemption from the penal laws. An example was Rhys ap Thomas ap Dafydd of Carmarthenshire who was a royal official in the southern part of the Principality.

Castles, towns and colonisation

Edward's main concern following the conquest was to ensure the military security of his new territories and the stone castle was to be the primary means for achieving this. Under the supervision ofJames of Saint George

Master James of Saint George (–1309; French: , Old French: Mestre Jaks, Latin: Magister Jacobus de Sancto Georgio) was a master of works/architect from Savoy, described by historian Marc Morris as "one of the greatest architects of the Europea ...

, Edward's master-builder, a series of imposing castles was built, using a distinctive design and the most advanced defensive features of the day, to form a "ring of stone" around the northern part of the principality. Among the major buildings were the castles of Beaumaris

Beaumaris ( ; cy, Biwmares ) is a town and community on the Isle of Anglesey in Wales, of which it is the former county town of Anglesey. It is located at the eastern entrance to the Menai Strait, the tidal waterway separating Anglesey from th ...

, Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a royal town, community and port in Gwynedd, Wales, with a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the eastern shore of the Menai Strait, opposite the Isle of Anglesey. The city of Bangor is ...

, Conwy

Conwy (, ), previously known in English as Conway, is a walled market town, community and the administrative centre of Conwy County Borough in North Wales. The walled town and castle stand on the west bank of the River Conwy, facing Deganwy on ...

and Harlech

Harlech () is a seaside resort and community in Gwynedd, north Wales and formerly in the historic county of Merionethshire. It lies on Tremadog Bay in the Snowdonia National Park. Before 1966, it belonged to the Meirionydd District of the 19 ...

. Aside from their practical military role, the castles made a clear symbolic statement to the Welsh that the principality was subject to English rule on a permanent basis.

Outside of urban areas, the principality retained its Welsh character. Unlike in some of the newly created Marcher lordships, such as Denbigh, there was little evidence of successful colonisation of rural areas by English settlers. For the royal shires, Edward established a series of new towns, usually attached to one of his stone castles, which would be the focus of English settlement. These “plantation boroughs

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

”, often with the castle constable as town mayor, were populated by English burgesses and acted as a support for the royal military establishment as well as being an anglicizing influence. Examples include Flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and sta ...

, Aberystwyth, Beaumaris

Beaumaris ( ; cy, Biwmares ) is a town and community on the Isle of Anglesey in Wales, of which it is the former county town of Anglesey. It is located at the eastern entrance to the Menai Strait, the tidal waterway separating Anglesey from th ...

, Conwy

Conwy (, ), previously known in English as Conway, is a walled market town, community and the administrative centre of Conwy County Borough in North Wales. The walled town and castle stand on the west bank of the River Conwy, facing Deganwy on ...

, and Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a royal town, community and port in Gwynedd, Wales, with a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the eastern shore of the Menai Strait, opposite the Isle of Anglesey. The city of Bangor is ...

.

The boroughs were given economic rights over the surrounding Welsh rural areas and prospered as a result. For example, the burgesses of Caernarfon had a monopoly over trade within eight miles of the town. The burgesses of Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

were given the right to raise taxes from the surrounding population to maintain their town walls. Royal ordinances initially prohibited the Welsh from becoming burgesses, owning land or even residing in the "English" towns. The enforcement of these laws weakened over time and, although they were temporarily reinforced in 1402 by Henry IV's Penal Laws following the Welsh Revolt

The Welsh Revolt (also called the Glyndŵr Rising or Last War of Independence) ( cy, Rhyfel Glyndŵr) or ( cy, Gwrthryfel Glyndŵr) was a Welsh rebellion in Wales led by Owain Glyndŵr against the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ag ...

led by Owain Glyndŵr, they had largely been abandoned by the Tudor period. Even so, in the 14th century in particular, the privileged "English" boroughs were a focus of intense Welsh resentment and the English burgesses continued to hold the Welsh in disdain and sought to maintain their own distinctiveness and settlers’ rights.

Nevertheless, there is ample evidence of the gradual assimilation of the two groups, not least through intermarriage. A town such as Aberystwyth had become entirely Welsh in character by the end of the medieval period. At the time of the union with England in the 16th century, English migrant ethnic origin ceased to have the same significance, although upward mobility was linked to anglicisation and use of the English language. Nevertheless, as late as 1532, a group of burgesses from Caernarfon bitterly complained that some of their number had let properties in the town to “foreigners”, all of whom had Welsh names.

Plantagenet and Tudor Princes

From 1301, thePlantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in ...

(and later, Tudor) English kings gave their heir apparent, if he was the king's son or grandson, the lands and title of "Prince of Wales". The one exception was Edward II's son, Edward of Windsor, who later became Edward III. Upon the heir's accession to the throne, the lands and title merged in the Crown.

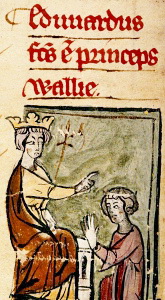

The first "English" Prince of Wales was Edward I's son, Edward of Caernarfon

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to the ...

. A late 16th-century story claimed that Edward I gave him the title following his declaration to the Welsh that there would be a Prince of Wales "that was borne in Wales and could speake never a word of English": Edward was born at Caernarfon Castle and, in common with rest of the English ruling elite, spoke French. However, there seems to be no basis for the story. On 7 February 1301, the king granted to Edward all the lands under royal control in Wales, mainly the territory of the former Principality. Although the documents granting the land made no reference to the title "Prince of Wales", it seems likely that Edward was invested with it at the same time, since, within a month of the grant, he was referred to as the "Prince of Wales" in official documents.

Edward of Caernarfon

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to the ...

, later Edward II (Prince from 1301 until he became King in 1307)

*Edward of Woodstock

Edward of Woodstock, known to history as the Black Prince (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), was the eldest son of King Edward III of England, and the List of heirs to the English throne, heir apparent to the English throne. He died before his fat ...

, the Black Prince (Prince from 1343 to his death in 1376)

* Richard of Bordeaux, later Richard II (Prince from 1376 until he became King in 1377)

*Henry of Monmouth

Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422), also called Henry of Monmouth, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1413 until his death in 1422. Despite his relatively short reign, Henry's outstanding military successes in the Hu ...

, later Henry V (Prince from 1399 until he became King in 1413)

*Edward of Westminster

Edward of Westminster (13 October 1453 – 4 May 1471), also known as Edward of Lancaster, was the only son of King Henry VI of England and Margaret of Anjou. He was killed aged seventeen at the Battle of Tewkesbury.

Early life

Edward was born ...

(Prince from 1454 until his death in 1471)

* Edward of the Sanctuary, later Edward V (Prince from 1471 until he became King in 1483)

*Edward of Middleham

Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales ( or 1476 9 April 1484), was the son and heir apparent of King Richard III of England by his wife Anne Neville. He was Richard's only legitimate child and died aged ten.

Birth and titles

Edward was born at ...

(Prince from 1483 to his death in 1484)

* Arthur Tudor (Prince from 1489 to his death in 1502)

* Henry Tudor, later Henry VIII (Prince from 1504 until he became King in 1509)

*Edward Tudor

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, later Edward VI (Prince from 1537 until he became King in 1547, the last Prince of Wales created prior to 1542)

Welsh revolts

Madog ap Llywelyn

Madog ap Llywelyn (died after 1312) was the leader of the Welsh revolt of 1294–95 against English rule in Wales and proclaimed "Prince of Wales". The revolt was surpassed in longevity only by the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr in the 15th century. Ma ...

led a Welsh revolt in 1294–95 against English rule in Wales, and was proclaimed "Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

".

Owain Lawgoch

Owain Lawgoch ( en, Owain of the Red Hand, french: Yvain de Galles), full name Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri (July 1378), was a Welsh soldier who served in Lombardy, France, Alsace, and Switzerland. He led a Free Company fighting for the French agai ...

, a great-nephew of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Dafydd ap Gruffudd, claimed the title in exile in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and supporters revolted in his name across Wales between 1372 and 1378. He was assassinated before being able to return to Wales to lead them.

Machynlleth

Machynlleth () is a market town, community and electoral ward in Powys, Wales and within the historic boundaries of Montgomeryshire. It is in the Dyfi Valley at the intersection of the A487 and the A489 roads. At the 2001 Census it had a pop ...

in 1404 during a revolt against Henry IV of England. He claimed descent from Rhodri Mawr

Rhodri ap Merfyn ( 820 – 873/877/878), popularly known as Rhodri the Great ( cy, Rhodri Mawr), succeeded his father, Merfyn Frych, as King of Gwynedd in 844. Rhodri annexed Powys c. 856 and Seisyllwg c. 871. He is called "King of the Britons" ...

through the House of Powys Fadog

Powys Fadog (English: ''Lower Powys'' or ''Madog's Powys'') was the northern portion of the former princely realm of Powys, which split in two following the death of Madog ap Maredudd in 1160. The realm was divided under Welsh law, with Madog's ...

. He went on to establish diplomatic relations with foreign powers and liberated Wales from English rule. He was ultimately unsuccessful and was driven to the mountains where he led a guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

. When and where he died is not known, but it is believed he died disguised as a friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

in the company of his daughter, Alys, at Monnington Straddle in Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthsh ...

.

Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542

The Principality ceased to exist as a legal entity with the passing byEnglish parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

of the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542, without any representation from Wales. The act stated that Wales was already ‘incorporated, annexed, united and subiecte to and under the imperialle Crown of this Realme as a very member…of the same’. The 1536 act, according to Dr John Davies unified the principality of Wales and the March of Wales

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the Wales-England border, border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh Mar ...

. The law of England was applied as the only law in Wales. The act also made English the only language of the courts in Wales and those using the Welsh language would not be able to take up office in the territories of the king of England. The implementation of the act was delayed until a more detailed act was used in 1543.

After 1543: union with England

Later administration

TheEncyclopaedia of Wales

The ''Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales'', published in January 2008, is a single-volume-publication encyclopaedia about Wales. The Welsh-language edition, entitled ''Gwyddoniadur Cymru'' is regarded as the most ambitious encyclopaedic work ...

notes that the Council of Wales and the Marches

The Court of the Council in the Dominion and Principality of Wales, and the Marches of the same, commonly called the Council of Wales and the Marches () or the Council of the Marches, was a regional administrative body based in Ludlow Castle wi ...

was created by Edward IV in 1471 as a household institution to manage the Prince of Wales's lands and finances. In 1473 it was enlarged and given the additional duty of maintaining law and order in the Principality and the Marches of Wales. Its meetings appear to have been intermittent, but it was revived by Henry VII for his heir, Prince Arthur. The Council was placed on a statutory basis in 1543 and played a central role in co-ordinating law and administration. It declined in the early 17th century and was abolished by Parliament in 1641. It was revived at the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

before being finally abolished in 1689.

From 1689 to 1948 there was no differentiation between the government of England and government in Wales. All laws relating to England included Wales and Wales was considered by the British Government as an indivisible part of England within the United Kingdom. The first piece of legislation to relate specifically to Wales was the Sunday Closing (Wales) Act 1881. A further exception was the Welsh Church Act 1914

The Welsh Church Act 1914 is an Act of Parliament under which the Church of England was separated and disestablished in Wales and Monmouthshire, leading to the creation of the Church in Wales. The Act had long been demanded by the Nonconformist ...

, which disestablished the Church in Wales

The Church in Wales ( cy, Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru) is an Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The p ...

(which had formerly been part of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

) in 1920.

In 1948 the practice was established that all laws passed in the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

were designated as applicable to either "England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

" or "Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

", thus returning a legal identity to Wales which had not existed for hundreds of years following the Act of Union with Scotland in 1707. Also in 1948 a new Council for Wales was established as a parliamentary committee. In 1964 the Welsh Office

The Welsh Office ( cy, Swyddfa Gymreig) was a department in the Government of the United Kingdom with responsibilities for Wales. It was established in April 1965 to execute government policy in Wales, and was headed by the Secretary of State f ...

was established, based in London, to oversee and recommend improvements to the application of laws in Wales. This situation would continue until the devolution of government in Wales and the establishment of the autonomous National Assembly for Wales

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh Go ...

in 1998.

Other uses of the term

Although no principality has ever been created that covers Wales as a whole, the term "Principality" has been occasionally used since the sixteenth century as a synonym for Wales. For instance, the firstatlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geograp ...

of Wales, by Thomas Taylor in 1718, was titled ''The Principality of Wales exactly described ...'', and the term is still used by such publications as ''Burke's Landed Gentry

''Burke's Landed Gentry'' (originally titled ''Burke's Commoners'') is a reference work listing families in Great Britain and Ireland who have owned rural estates of some size. The work has been in existence from the first half of the 19th cen ...

''. Publications such as Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

's ''A Topographical Dictionary of Wales'', and Welsh newspapers in the 19th century commonly used the term.

In modern times, however, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' style guide advises writers to "avoid the word 'principality in relation to Wales. The International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ) is an international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries. Membership requirements are given in Art ...

(ISO) has defined Wales as a "country" rather than a "principality" since 2011, following a recommendation by the British Standards Institute

The British Standards Institution (BSI) is the national standards body of the United Kingdom. BSI produces technical standards on a wide range of products and services and also supplies certification and standards-related services to business ...

and the Welsh Government

, image =

, caption =

, date_established =

, country = Wales

, address =

, leader_title = First Minister ()

, appointed = First Minister approved by the Senedd, ceremonially appointed ...

.

The use of the term to refer to the territory of Wales should be distinguished from its use to refer to the title of Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, which has been traditionally granted (together with the title Duke of Cornwall and various Scottish titles) to the heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

of the reigning British monarch. It confers no responsibility for government in Wales, and has no constitutional meaning. Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left to left-wing, Welsh nationalist political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from the United Kingdom.

Plaid wa ...

are in favour of scrapping the title altogether. The Honours of the Principality of Wales

The Honours of the Principality of Wales are the regalia used at the investiture of the Prince of Wales, as heir apparent to the British throne, made up of a coronet, a ring, a rod, a sword, a girdle, and a mantle. All but the coronet date fro ...

are the Crown Jewels used at the investiture of Princes of Wales.

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Principality of Wales 1282 disestablishments in EuropeWales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

Medieval Wales

12th century in Wales

13th century in Wales

14th century in Wales

15th century in Wales

16th century in Wales

States and territories established in 1216

States and territories disestablished in 1542