Presidency of Chester A. Arthur on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

After President

After President

In the early 1880s, American politics operated on the

In the early 1880s, American politics operated on the

During his brief tenure in the Garfield and Arthur administrations, Secretary of State James G. Blaine attempted to invigorate United States diplomacy in

During his brief tenure in the Garfield and Arthur administrations, Secretary of State James G. Blaine attempted to invigorate United States diplomacy in

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete. The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete. The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the

Like his Republican predecessors, Arthur struggled with the question of how his party was to challenge the Democrats in the South and how, if at all, to protect the civil rights of black Southerners. Since the end of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats (or "

Like his Republican predecessors, Arthur struggled with the question of how his party was to challenge the Democrats in the South and how, if at all, to protect the civil rights of black Southerners. Since the end of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats (or "

Arthur played no role in the 1884 campaign, which Blaine would later blame for his loss that November to the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland. Blaine's campaign was damaged by the defection of the

Arthur played no role in the 1884 campaign, which Blaine would later blame for his loss that November to the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland. Blaine's campaign was damaged by the defection of the

Arthur's tepid popularity in life carried over into his assessment by historians, and his reputation after leaving office disappeared. By 1935, historian George F. Howe said that Arthur had achieved "an obscurity in strange contrast to his significant part in American history." By 1975, however, Thomas C. Reeves would write that Arthur's "appointments, if unspectacular, were unusually sound; the corruption and scandal that dominated business and politics of the period did not tarnish his administration." As 2004 biographer Zachary Karabell wrote, although Arthur was "physically stretched and emotionally strained, he strove to do what was right for the country." Indeed, Howe had earlier surmised, "Arthur adopted codefor his own political behavior but subject to three restraints: he remained to everyone a man of his word; he kept scrupulously free from corrupt graft; he maintained a personal dignity, affable and genial though he might be. These restraints ... distinguished him sharply from the stereotype politician." In his final assessment of Arthur, Karabell argues that Arthur lacked the vision or force of character to achieve greatness, but that he deserves credit for presiding over a period of peace and prosperity.

Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Arthur as a below-average president. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Arthur as the 29th best president. A 2017 C-SPAN survey has Chester Arthur ranked among the bottom third of presidents of all time, right below Martin Van Buren and above Herbert Hoover. The survey asked 91 presidential historians to rank the 43 former presidents (including then-outgoing president Barack Obama) in various categories to come up with a composite score, resulting in an overall ranking. Arthur was ranked 35th among all former presidents (down from 32nd in 2009 and 2000). His rankings in the various categories of this most recent poll were as follows: public persuasion (37), crisis leadership (32), economic management (31), moral authority (35), international relations (35), administrative skills (28), relations with congress (29), vision/setting an agenda (34), pursued equal justice for all (27), performance with context of times (32).

Arthur's tepid popularity in life carried over into his assessment by historians, and his reputation after leaving office disappeared. By 1935, historian George F. Howe said that Arthur had achieved "an obscurity in strange contrast to his significant part in American history." By 1975, however, Thomas C. Reeves would write that Arthur's "appointments, if unspectacular, were unusually sound; the corruption and scandal that dominated business and politics of the period did not tarnish his administration." As 2004 biographer Zachary Karabell wrote, although Arthur was "physically stretched and emotionally strained, he strove to do what was right for the country." Indeed, Howe had earlier surmised, "Arthur adopted codefor his own political behavior but subject to three restraints: he remained to everyone a man of his word; he kept scrupulously free from corrupt graft; he maintained a personal dignity, affable and genial though he might be. These restraints ... distinguished him sharply from the stereotype politician." In his final assessment of Arthur, Karabell argues that Arthur lacked the vision or force of character to achieve greatness, but that he deserves credit for presiding over a period of peace and prosperity.

Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Arthur as a below-average president. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Arthur as the 29th best president. A 2017 C-SPAN survey has Chester Arthur ranked among the bottom third of presidents of all time, right below Martin Van Buren and above Herbert Hoover. The survey asked 91 presidential historians to rank the 43 former presidents (including then-outgoing president Barack Obama) in various categories to come up with a composite score, resulting in an overall ranking. Arthur was ranked 35th among all former presidents (down from 32nd in 2009 and 2000). His rankings in the various categories of this most recent poll were as follows: public persuasion (37), crisis leadership (32), economic management (31), moral authority (35), international relations (35), administrative skills (28), relations with congress (29), vision/setting an agenda (34), pursued equal justice for all (27), performance with context of times (32).

online

* * * * Pletcher, David M. ''The Awkward Years: American Foreign Relations under Garfield and Arthur'' (U of Missouri Press, 1962)

online

* *

online

* * Gaughan, Anthony J. "Chester Arthur's Ghost: A Cautionary Tale of Campaign Finance Reform." ''Mercer Law Review'' 71 (2019): 779+. * * * * * *

Essays on Chester Arthur and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady

from the

Chester Arthur: A Resource Guide

from the

"Life Portrait of Chester A. Arthur"

from C-SPAN's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', August 6, 1999

"Life and Career of Chester A. Arthur"

presentation by Zachary Karabell at the Kansas City Public Library, May 23, 2012

''Chester A. Arthur's Presidency''

a video by History.com

Chester A. Arthur's Personal Manuscripts

fro

Shapell.org

{{Authority control 1880s in the United States Arthur, Chester A. 1881 establishments in the United States 1885 disestablishments in the United States

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James ...

's tenure as the 21st president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

began on September 19, 1881, when he succeeded to the presidency upon the assassination of President James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

, and ended on March 4, 1885. Arthur, a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, had been vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

for days when he succeeded to the presidency. In ill health and lacking the full support of his party by the end of his term, Arthur made only a token effort for the Republican presidential nomination in the 1884 presidential election. He was succeeded by Democrat Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

.

Garfield chose Arthur as his running mate in the 1880 United States presidential election

The 1880 United States presidential election was the 24th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 2, 1880, in which Republican nominee James A. Garfield defeated Winfield Scott Hancock of the Democratic Party. The voter ...

due to the latter's association with the Republican Party's Stalwart faction, and Arthur struggled to overcome his reputation as a New York City machine politician. He embraced the cause of U.S. Civil Service Reform, and his advocacy and enforcement of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

became the centerpiece of his administration. Though patronage remained a powerful force in politics, the Pendleton Act laid the foundations for a professional civil service that would emerge in subsequent decades. Facing a budget surplus, Arthur signed the Tariff of 1883, which reduced tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

. He also vetoed the Rivers and Harbors Act

Rivers and Harbors Act may refer to one of many pieces of legislation and appropriations passed by the United States Congress since the first such legislation in 1824. At that time Congress appropriated $75,000 to improve navigation on the Ohio and ...

, an act that would have appropriated federal funds in a manner he thought excessive, and oversaw a building program for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. After the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, Arthur favored new civil rights legislation to protect African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

s, but was unable to win passage of a new bill. In foreign policy, Arthur pursued closer economic and political relations with Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

, but many of his proposed trade agreements were defeated in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

.

The 1884 Republican National Convention passed over Arthur in favor of James G. Blaine, but Cleveland defeated Blaine in the 1884 presidential election. Although Arthur's failing health and political temperament combined to make his administration less active than a modern presidency, he earned praise among contemporaries for his solid performance in office. Journalist Alexander McClure

Alexander Kelly McClure (January 9, 1828 – June 6, 1909) was an American politician, newspaper editor, and writer from Pennsylvania who served as a Republican member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives from 1858 to 1859, the Penns ...

later wrote, "No man ever entered the presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired ... more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe." Since his death, Arthur's reputation has mostly faded from the public consciousness. Although some have praised his flexibility and willingness to embrace reform, present-day historians and scholars generally rank him as a below-average president.

Accession

After President

After President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

declined to seek re-election in 1880

Events

January–March

* January 22 – Toowong State School is founded in Queensland, Australia.

* January – The international White slave trade affair scandal in Brussels is exposed and attracts international infamy.

* February � ...

, several candidates vied for the presidential nomination at the 1880 Republican National Convention. The convention dead-locked between supporters of former President Ulysses S. Grant and Senator James G. Blaine, resulting in the nomination of a dark horse candidate, James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

. Hoping to unite the Republican Party behind his candidacy, Garfield decided to select a follower of New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, a leader of the party's Stalwart faction, as his running mate. Garfield settled on Arthur, a former Collector of the Port of New York

The Collector of Customs at the Port of New York, most often referred to as Collector of the Port of New York, was a federal officer who was in charge of the collection of import duties on foreign goods that entered the United States by ship at t ...

who was closely allied with Conkling. The Garfield-Arthur ticket won the 1880 presidential election, but after taking office, Garfield clashed with Conkling over appointments and other issues. Arthur's continued loyalty to Conkling marginalized him within the Garfield administration and, after the Senate went into recess in May 1881, Arthur returned to his home state of New York.

On July 2, 1881, Arthur learned that Garfield had been badly wounded in a shooting. The shooter, Charles J. Guiteau, was a deranged office-seeker who believed that Garfield's successor would appoint him to a patronage job. Though he had barely known Guiteau, Arthur had to allay suspicions that he had been behind the assassination. He was reluctant to be seen acting as president while Garfield lived, and in the months after the shooting, with Garfield near death and Arthur still in New York, there was a void of authority in the executive office. Many worried about the prospect of an Arthur presidency; the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

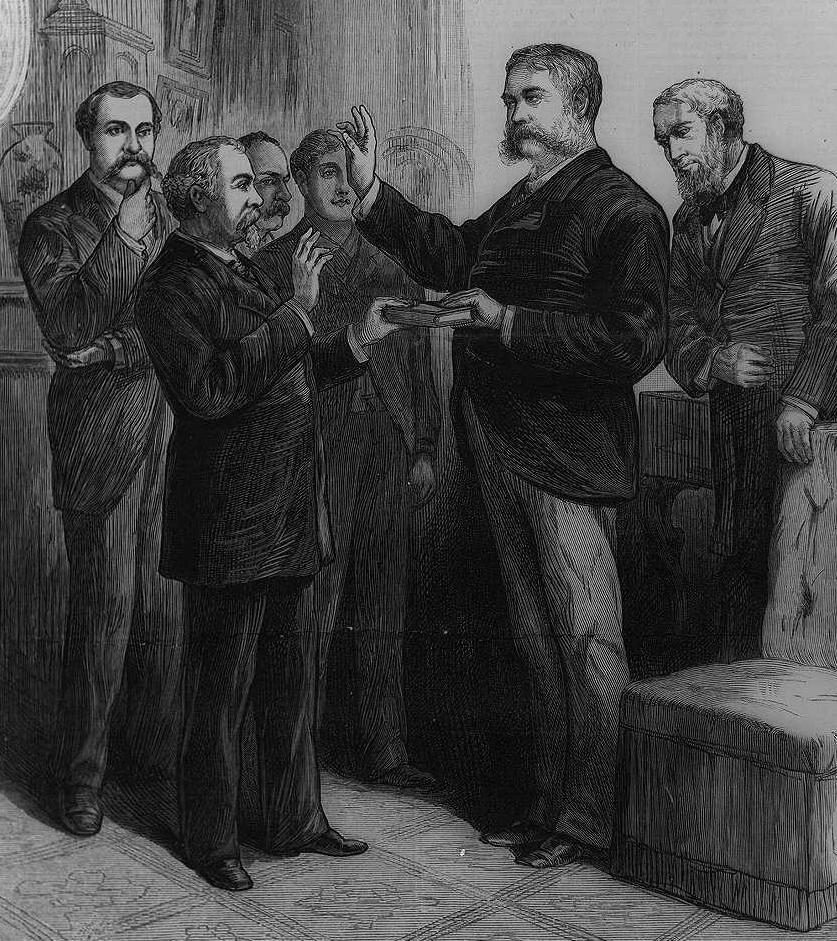

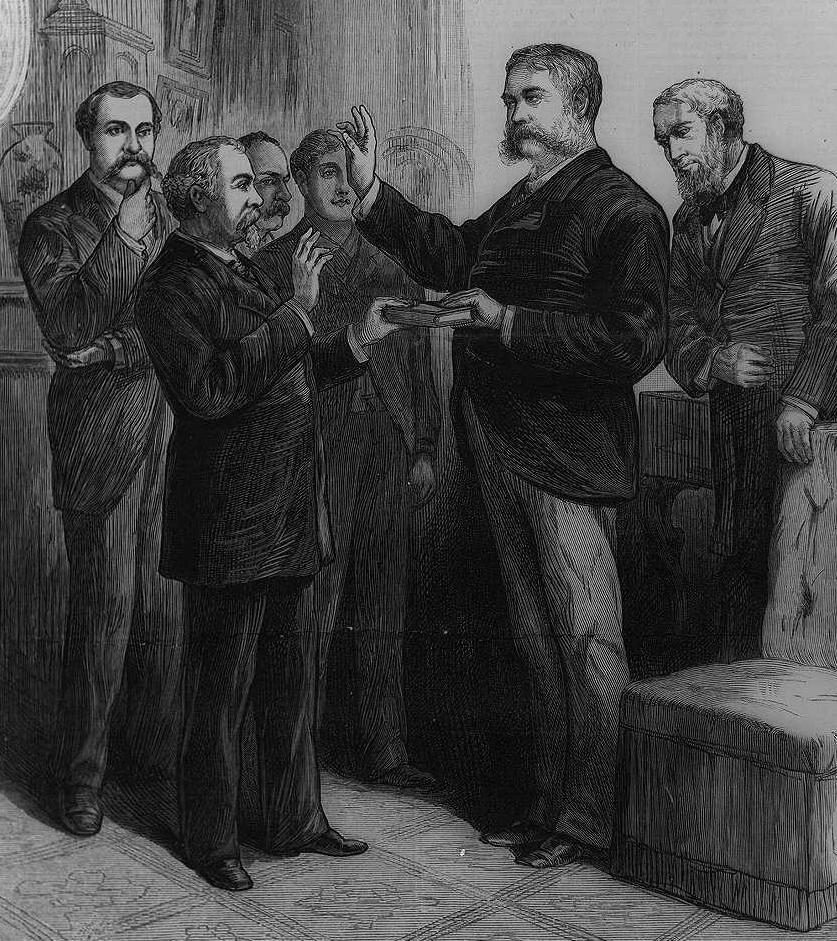

'', which had supported Arthur earlier in his career, wrote "Arthur is about the last man who would be considered eligible for the position." Garfield died on September 19, and Judge John R. Brady of the New York Supreme Court administered the oath of office to Arthur in the latter's New York City home at 2:15 a.m. on September 20. Before leaving New York, Arthur ensured the presidential line of succession by preparing and mailing to the White House a proclamation calling for a Senate special session, thus ensuring that the Senate could select a president pro tempore, who would be first in the presidential line of succession.

On September 22, Arthur re-took the oath of office, this time before Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite. He took this step to ensure procedural compliance; there were lingering questions about whether Brady, a state court judge, could administer a federal oath of office. Arthur ordered a remodeling of the White House and took up residence at the home of Senator John P. Jones until December 1881, when he moved into the White House. As Arthur was a widower, his sister, Mary Arthur McElroy, served as the de facto First Lady of the United States. Arthur took office over a growing country (population had increased from 30 million in 1860 to 50 million in 1880) that maintained a budget surplus and peaceful relations with the great powers of the day.

Administration

Arthur quickly came into conflict with Garfield's cabinet, most of whom represented opposing factions within the party. At the same time, he distanced himself from Conkling, and he sought to appoint officials who were well-regarded by both reformers and party loyalists. Arthur asked Garfield's cabinet members to remain until December 1881, when Congress would reconvene, but Treasury SecretaryWilliam Windom

William Windom (May 10, 1827January 29, 1891) was an American politician from Minnesota. He served as U.S. Representative from 1859 to 1869, and as U.S. Senator from 1870 to January 1871, from March 1871 to March 1881, and from November 1881 ...

submitted his resignation in October to enter a Senate race in his home state of Minnesota. Arthur then selected Charles J. Folger, his friend and a fellow New York Stalwart, as Windom's replacement. Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh

Isaac Wayne MacVeagh (April 19, 1833January 11, 1917) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat. He served as the 36th Attorney General of the United States under the administrations of Presidents James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur ...

was next to resign, believing that, as a reformer, he had no place in an Arthur cabinet. Arthur replaced MacVeagh with Benjamin H. Brewster, a Philadelphia lawyer and machine politician reputed to have reformist leanings. Secretary of State Blaine, one of the key leaders of the Half-Breed

Half-breed is a term, now considered offensive, used to describe anyone who is of mixed race; although, in the United States, it usually refers to people who are half Native American and half European/white.

Use by governments United States

I ...

faction of the Republican Party, also resigned in December.

Conkling expected Arthur to appoint him in Blaine's place, as he had been Arthur's patron for much of the latter's career. But the president chose Frederick T. Frelinghuysen

Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen (August 4, 1817May 20, 1885) was an American lawyer and politician from New Jersey who served as a U.S. Senator and later as United States Secretary of State under President Chester A. Arthur.

Early life and ...

of New Jersey, a Stalwart recommended by former President Grant. Though Frelinghuysen advised Arthur not to fill any future vacancies with Stalwarts, Arthur selected Timothy O. Howe, a Wisconsin Stalwart, to replace Postmaster General Thomas Lemuel James after the latter resigned in January 1882. Navy Secretary William H. Hunt was next to resign, in April 1882, and Arthur attempted to placate the Half-Breeds by appointing William E. Chandler, who had been recommended by Blaine. Finally, when Interior Secretary Samuel J. Kirkwood resigned that same month, Arthur appointed Henry M. Teller, a Colorado Stalwart, to the office. Of the cabinet members Arthur had inherited from Garfield, only Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln (August 1, 1843 – July 26, 1926) was an American lawyer, businessman, and politician. He was the eldest son of President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln. Robert Lincoln became a business lawyer and company presi ...

remained for the entirety of Arthur's term.

Judicial appointments

Arthur made appointments to fill two vacancies on theUnited States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

. The first vacancy arose in July 1881 with the death of Associate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

Nathan Clifford, a Democrat who had been a member of the Court since before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Arthur nominated Horace Gray, a distinguished jurist from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, to replace Clifford, and the nomination was easily confirmed. Gray would remain on the Court until 1902. A second vacancy occurred when Associate Justice Ward Hunt retired in January 1882. Arthur first nominated his old political boss, Roscoe Conkling; he doubted that Conkling would accept, but felt obligated to offer a high office to his former patron. The Senate confirmed the nomination but, as expected, Conkling declined it, the last time a confirmed nominee declined an appointment. Senator George Edmunds was Arthur's next choice, but he declined to be considered. Instead, Arthur nominated Samuel Blatchford, who had been a judge on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory comprises the states of Connecticut, New York and Vermont. The court has appellate juri ...

for the prior four years. Blatchford accepted, and his nomination was approved by the Senate within two weeks. Blatchford served on the Court until his death in 1893.

In addition to his two Supreme Court appointments, Arthur also appointed four circuit court judges and fourteen district court judges.

Civil service reform

Pendleton Act

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

, a political patronage practice in which victorious candidates rewarded their loyal supporters, family, and friends by installing them in government civil service positions. Movements calling for Civil Service Reform arose in the wake of the corruption in the Grant Administration. In 1880, Democratic Senator George H. Pendleton

George Hunt Pendleton (July 19, 1825November 24, 1889) was an American politician and lawyer. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1864.

After study ...

of Ohio had introduced legislation to require the selection of civil servants based on merit as determined by an examination. The measure failed to pass, but Garfield's assassination by a deranged office seeker amplified the public demand for reform. Late in 1881, in his first annual address to Congress, Arthur requested civil service reform legislation, and Pendleton again introduced his bill, which again did not pass.

Then, in the 1882 congressional elections, Republicans suffered a crushing defeat. The party lost its majority control in the House of Representatives, as Democrats, campaigning on the reform issue, defeated 40 Republican incumbents and picked up a total of 70 seats. This defeat helped convince many Republicans to support the reform proposal during the 1882 lame-duck session of Congress; the Senate approved the bill 38–5 and the House soon concurred by a vote of 155–47. Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

into law on January 16, 1883. The bill created a civil service commission to oversee civil service examinations and outlawed the use of "assessments," fees that political appointees were expected to pay to their respective political parties as the price for their appointments. These reforms had previously been proposed by the Jay Commission, which had investigated Arthur during his time as Collector of the Port of New York. In just two years' time, an unrepentant Stalwart had become the president who ushered in long-awaited civil service reform.

Even after Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act into law, proponents of the act doubted Arthur's commitment to reform. The act initially applied only to ten percent of federal jobs and, without proper implementation by the president, would not have affected the remaining civil service positions. To the surprise of his critics, Arthur acted quickly to appoint the members of the newly created Civil Service Commission

A civil service commission is a government agency that is constituted by legislature to regulate the employment and working conditions of civil servants, oversee hiring and promotions, and promote the values of the public service. Its role is rough ...

, naming reformers Dorman Bridgman Eaton, John Milton Gregory, and Leroy D. Thoman as commissioners. The chief examiner, Silas W. Burt, was a long-time reformer who had been Arthur's opponent when the two men worked at the New York Customs House. The commission issued its first rules in May 1883; by 1884, half of all postal officials and three-quarters of the Customs Service jobs were to be awarded by merit. Arthur expressed satisfaction with the new system, praising its effectiveness "in securing competent and faithful public servants and in protecting the appointing officers of the Government from the pressure of personal importunity and from the labor of examining the claims and pretensions of rival candidates for public employment." Although state patronage systems and numerous federal positions were unaffected by the law, Karabell argues that the Pendleton Act was instrumental in the creation of a professional civil service and the rise of the modern bureaucratic

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

state. The law also caused major changes in campaign finance, as the parties were forced to look for new sources of campaign funds, such as wealthy donors.

Star Route scandal

In the late and early 1870s, the public had learned of the star route scandal, in which contractors for star postal routes were greatly overpaid for their services with the connivance of government officials, including former SenatorStephen Wallace Dorsey

Stephen Wallace Dorsey (February 28, 1842March 20, 1916) was a Republican politician who represented Arkansas in the United States Senate from 1873 to 1879, during the Reconstruction era.

He was born in Benson in Rutland County, Vermont, and ...

. Although Arthur had worked closely with Dorsey before his presidency, once in office he supported the investigation and forced the resignation of officials suspected in the scandal. An 1882 trial of the ringleaders resulted in convictions for two minor conspirators and a hung jury

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again.

T ...

for the rest. After a juror came forward with allegations that the defendants attempted to bribe him, the judge set aside the guilty verdicts and granted a new trial. Before the second trial began, Arthur removed five federal office holders who were sympathetic with the defense, including a former senator. The second trial began in December 1882 and lasted until July 1883 and, again, did not result in a guilty verdict. Failure to obtain a conviction tarnished the administration's image, but Arthur did succeed in putting a stop to the fraud.

Surplus and the tariff

With high revenue held over from wartime taxes, the federal government had collected more than it spent since 1866; by 1882 the surplus reached $145 million. Opinions varied on how to reduce the budget surplus; the Democrats favored reducing the surplus by loweringtariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

, which would in turn reduce the cost of imported goods. Republicans believed that high tariffs ensured high wages in manufacturing and mining, and they preferred reducing the surplus through spending more on internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and cutting excise

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

taxes. The debate over the tariff was complicated by the fact that each interest preferred higher tariffs for their particular field; many Southerners, for example, preferred low tariffs in general but favored higher tariffs for cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

, a major crop in the South. These competing interests led to the development of a complicated tariff system that levied different rates on different imports.

Arthur agreed with his party, and in 1882 called for the abolition of excise taxes on everything except liquor, as well as a simplification of the complex tariff structure. In May 1882, Representative William D. Kelley of Pennsylvania introduced a bill to establish a tariff commission. Arthur signed the bill into law and appointed mostly protectionists to the committee. Republicans were pleased with the committee's make-up but were surprised when, in December 1882, the committee submitted a report to Congress calling for tariff cuts averaging between 20 percent and 25 percent. The commission's recommendations were ignored, however, as the House Ways and Means Committee

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other progra ...

, dominated by protectionists, passed a bill providing for a 10 percent reduction in tariff rates. After a conference with the Senate, the bill that emerged only reduced tariffs by an average of 1.47 percent. The bill passed both houses narrowly on March 3, 1883, the last full day of the 47th Congress. Arthur signed the measure into law, and it had no effect on the budget surplus.

Congress attempted to balance the budget from the other side of the ledger, with increased spending on the 1882 Rivers and Harbors Act

Rivers and Harbors Act may refer to one of many pieces of legislation and appropriations passed by the United States Congress since the first such legislation in 1824. At that time Congress appropriated $75,000 to improve navigation on the Ohio and ...

in the unprecedented amount of $19 million. While Arthur was not opposed to internal improvements, the scale of the bill disturbed him, as did what he saw as its narrow focus on "particular localities" rather than projects that benefited a larger part of the nation. On August 1, 1882, Arthur vetoed the bill to widespread popular acclaim; in his veto message, his principal objection was that it appropriated funds for purposes "not for the common defense or general welfare, and which do not promote commerce among the States." Congress overrode his veto the next day and the new law reduced the surplus by $19 million. Republicans considered the law a success at the time, but later concluded that it contributed to their loss of seats in the elections of 1882.

Foreign affairs and immigration

During his brief tenure in the Garfield and Arthur administrations, Secretary of State James G. Blaine attempted to invigorate United States diplomacy in

During his brief tenure in the Garfield and Arthur administrations, Secretary of State James G. Blaine attempted to invigorate United States diplomacy in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

, urging reciprocal trade agreements and offering to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations. Blaine hoped that increased U.S. involvement in the region would counter growing European (particularly British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

) influence in the Western Hemisphere. Blaine proposed a Pan-American conference in 1882 to discuss trade and an end to the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific ( es, link=no, Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War ( es, link=no, Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought ...

, but conference efforts lapsed after Blaine was replaced by Frelinghuysen in late 1881. On the other hand, Arthur and Frelinghuysen continued Blaine's efforts to encourage trade among the nations of the Western Hemisphere; a treaty with Mexico providing for reciprocal tariff reductions was signed in 1882 and approved by the Senate in 1884. Legislation required to bring the treaty into force failed in the House, however. Similar efforts at reciprocal trade treaties with Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

and Spain's American colonies were defeated by February 1885, and an existing reciprocity treaty with the Kingdom of Hawaii was allowed to lapse. The Frelinghuysen- Zavala Treaty, which would have allowed the United States to build a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

, was also defeated in the Senate.

The 47th Congress spent a great deal of time on immigration. In July 1882, Congress easily passed a bill regulating steamships that carried immigrants to the United States. To their surprise, Arthur vetoed it and requested revisions, which they made and Arthur then approved. Arthur also signed the Immigration Act of 1882, which levied a 50-cent tax on immigrants to the United States, and excluded from entry the mentally ill

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

, the intellectually disabled, criminals, or any other person potentially dependent upon public assistance.

Chinese immigration was a major political issue in the 1870s and 1880s, and it became a subject of debate in the 47th Congress. When Arthur took office, there were 250,000 Chinese immigrants in the United States, most of whom lived in California and worked as farmers or laborers. In January 1868, the Senate had ratified the Burlingame Treaty

The Burlingame Treaty (), also known as the Burlingame–Seward Treaty of 1868, was a landmark treaty between the United States and Qing China, amending the Treaty of Tientsin, to establish formal friendly relations between the two nations, with ...

with China, allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese into the country; when the economy soured after the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, many Americans blamed Chinese immigrants for depressing workmen's wages. In 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes vetoed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which would have abrogated the Burlingame Treaty. Three years later, after China had agreed to treaty revisions, Congress tried again to exclude Chinese immigrants; Senator John F. Miller of California introduced another Chinese Exclusion Act that denied Chinese immigrants United States citizenship and banned their immigration for a twenty-year period. Miller's bill passed the Senate and House by overwhelming margins, but Arthur vetoed the bill, as he believed that the twenty-year ban breached the renegotiated treaty of 1880. That treaty allowed only a "reasonable" suspension of immigration. Eastern newspapers praised the veto, while it was condemned in the Western states. Congress was unable to override the veto, but passed a new bill reducing the immigration ban to ten years. Although he still objected to this denial of citizenship to Chinese immigrants, Arthur acceded to the compromise measure, signing the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

into law on May 6, 1882.

Naval reform

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete. The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete. The nation's military focus over the fifteen years before Garfield and Arthur's election had been on the Indian wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

in the West, rather than the high seas, but as the region was increasingly pacified, many in Congress grew concerned at the poor state of the Navy. Garfield's Secretary of the Navy, William H. Hunt, had advocated reform of the Navy and his successor, William E. Chandler, appointed an advisory board to prepare a report on modernization. Based on the suggestions in the report, Congress appropriated funds for the construction of three steel protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

s (''Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

'', ''Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

'', and ''Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

'') and an armed dispatch-steamer (''Dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

''), collectively known as the ''ABCD Ships'' or the ''Squadron of Evolution

The Squadron of Evolution—sometimes referred to as the "White Squadron"— was a transitional unit in the United States Navy during the late 19th century. It was probably inspired by the French "Escadre d'évolution" of the 18th and 19th centur ...

''. Congress also approved funds to rebuild four monitors (''Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

'', '' Amphitrite'', '' Monadnock'', and '' Terror''), which had lain uncompleted since 1877. Arthur strongly supported these efforts, believing that a strengthened navy would not only increase the country's security but also enhance U.S. prestige. The contracts to build the ABCD ships were all awarded to the low bidder, John Roach & Sons of Chester, Pennsylvania, even though Roach once employed Secretary Chandler as a lobbyist. Democrats turned against the "New Navy" projects and, when they won control of the 48th Congress, refused to appropriate funds for seven more steel warships. Even without the additional ships, the state of the Navy improved when, after several construction delays, the last of the new ships entered service in 1889.

Civil rights and the South

Like his Republican predecessors, Arthur struggled with the question of how his party was to challenge the Democrats in the South and how, if at all, to protect the civil rights of black Southerners. Since the end of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats (or "

Like his Republican predecessors, Arthur struggled with the question of how his party was to challenge the Democrats in the South and how, if at all, to protect the civil rights of black Southerners. Since the end of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats (or "Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

s") had regained power in the South, and the Republican Party dwindled rapidly as their primary supporters in the region, blacks, were disenfranchised. One crack in the solidly Democratic South emerged with the growth of a new party, the Readjusters

The Readjuster Party was a bi-racial state-level political party formed in Virginia across party lines in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the Reconstruction era that sought to reduce outstanding debt owed by the state. Readj ...

, in Virginia. Having won an election in that state on a platform of more education funding (for black and white schools alike) and abolition of the poll tax and the whipping post

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stocks ...

, many northern Republicans saw the Readjusters as a more viable ally in the South than the moribund Southern Republican party. Arthur agreed, and directed the federal patronage in Virginia through the Readjusters rather than the Republicans. He followed the same pattern in other Southern states, forging coalitions with independents and Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

members. Some black Republicans felt betrayed by the pragmatic gambit, but others (including Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

and ex-Senator Blanche K. Bruce) endorsed the administration's actions, as the Southern independents had more liberal racial policies than the Democrats. Arthur's coalition policy was only successful in Virginia, however, and by 1885 the Readjuster movement had begun to collapse.

Other federal action on behalf of blacks was equally ineffective: when the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in the ''Civil Rights Cases

The ''Civil Rights Cases'', 109 U.S. 3 (1883), were a group of five landmark cases in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments did not empower Congress to outlaw racial discrimination by pr ...

'' (1883), Arthur expressed his disagreement with the decision in a message to Congress, but was unable to persuade Congress to pass any new legislation in its place. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 had banned discrimination in public accommodations

In United States law, public accommodations are generally defined as facilities, whether publicly or privately owned, that are used by the public at large. Examples include retail stores, rental establishments, and service establishments as well ...

, and its overturning was an important component in the rise of the Jim Crow era

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the So ...

of segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

and discrimination. Arthur did, however, effectively intervene to overturn a court-martial ruling against a black West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

cadet, Johnson Whittaker, after the Judge Advocate General of the Army, David G. Swaim, found the prosecution's case against Whittaker to be illegal and based on racism.

The administration faced a different challenge in the West, where the LDS Church

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The c ...

was under government pressure to stop the practice of polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is ...

in Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

. Garfield had believed polygamy was criminal behavior and was morally detrimental to family values, and Arthur's views were, for once, in line with his predecessor's. In 1882, he signed the Edmunds Act into law; the legislation made polygamy a federal crime, barring polygamists both from public office and the right to vote.

Native American policy

The Arthur administration was challenged by changing relations with Western Native American tribes. With theAmerican Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

winding down, public sentiment was shifting toward more favorable treatment of Native Americans. Arthur urged Congress to increase funding for Native American education, which it did in 1884, although not to the extent he wished. He also favored a move to the allotment system, under which individual Native Americans, rather than tribes, would own land. Arthur was unable to convince Congress to adopt the idea during his administration but, in 1887, the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pres ...

changed the law to favor such a system. The allotment system was favored by liberal reformers at the time, but eventually proved detrimental to Native Americans as most of their land was resold at low prices to white speculators. During Arthur's presidency, settlers and cattle ranchers continued to encroach on Native American territory. Arthur initially resisted their efforts, but after Secretary of the Interior Teller, an opponent of allotment, assured him that the lands were not protected, Arthur opened up the Crow Creek Reservation in the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

to settlers by executive order in 1885. Arthur's successor, Grover Cleveland, finding that title belonged to the Native Americans, revoked the order a few months later.

Health, travel, and 1884 election

Declining health

Shortly after becoming president, Arthur was diagnosed withBright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied ...

, a kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blo ...

ailment now referred to as nephritis. He attempted to keep his condition private, but by 1883 rumors of his illness began to circulate; he had become thinner and more aged in appearance, and struggled to keep the pace of the presidency. To rejuvenate his health outside the confines of Washington, Arthur and some political friends traveled to Florida in April 1883. The vacation had the opposite effect, and Arthur suffered from intense pain before returning to Washington. Shortly after returning from Florida, Arthur visited his home town of New York City, where he presided over the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge. In July, on the advice of Missouri Senator George Graham Vest

George Graham Vest (December 6, 1830August 9, 1904) was a U.S. politician. Born in Frankfort, Kentucky, he was known for his skills in oration and debate. Vest, a lawyer as well as a politician, served as a Missouri Congressman, a Confederate ...

, he visited Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowst ...

. Reporters accompanied the presidential party, helping to publicize the new National Park system

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

. The Yellowstone trip was more beneficial to Arthur's health than his Florida excursion, and he returned to Washington refreshed after two months of travel.

1884 election

As the election approached, Arthur came to realize that, like Hayes in 1880, he was unlikely to win renomination in 1884. In the months leading up to the 1884 Republican National Convention, James G. Blaine emerged as the favorite for the nomination, though Arthur had not totally given up on his hopes for another term. It quickly became clear to Arthur, however, that neither of the major party factions was prepared to give him their full support: the Half-Breeds were again solidly behind Blaine, while the Stalwarts were undecided. Some Stalwarts backed Arthur, but others supported Senator John A. Logan of Illinois. Reform-minded Republicans, friendlier to Arthur after he endorsed civil service reform, were still not certain enough of his reform credentials to back him over Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont, who had long favored their cause. Some business leaders supported Arthur, as did Southern Republicans who owed their jobs to his control of the patronage, but by the time they began to rally around him, Arthur had decided against a serious campaign for the nomination. He kept up a token effort, believing that to drop out would cast doubt on his actions in office and raise questions about his health, but by the time the convention began in June, his defeat was assured. Blaine led on the first ballot, and by the fourth ballot he had a majority. Arthur telegraphed his congratulations to Blaine and accepted his defeat with equanimity. Arthur is the most recent individual to accede to the presidency after the death of a predecessor but be denied his party's nomination to a full term.Mugwumps

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

, a group of Republicans who believed that the Pendleton Act had not sufficiently diminished public corruption. Blaine also made a critical error in the swing state

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pres ...

of New York when he failed to distance himself from an attack on Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Cleveland swept the Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

and won enough Northern states to take a majority of the electoral vote. A change of just 1,000 votes in New York would have given Blaine the presidency. Cleveland's victory made him the first Democrat to win a presidential election since the Civil War.

Historical reputation

Arthur's tepid popularity in life carried over into his assessment by historians, and his reputation after leaving office disappeared. By 1935, historian George F. Howe said that Arthur had achieved "an obscurity in strange contrast to his significant part in American history." By 1975, however, Thomas C. Reeves would write that Arthur's "appointments, if unspectacular, were unusually sound; the corruption and scandal that dominated business and politics of the period did not tarnish his administration." As 2004 biographer Zachary Karabell wrote, although Arthur was "physically stretched and emotionally strained, he strove to do what was right for the country." Indeed, Howe had earlier surmised, "Arthur adopted codefor his own political behavior but subject to three restraints: he remained to everyone a man of his word; he kept scrupulously free from corrupt graft; he maintained a personal dignity, affable and genial though he might be. These restraints ... distinguished him sharply from the stereotype politician." In his final assessment of Arthur, Karabell argues that Arthur lacked the vision or force of character to achieve greatness, but that he deserves credit for presiding over a period of peace and prosperity.

Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Arthur as a below-average president. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Arthur as the 29th best president. A 2017 C-SPAN survey has Chester Arthur ranked among the bottom third of presidents of all time, right below Martin Van Buren and above Herbert Hoover. The survey asked 91 presidential historians to rank the 43 former presidents (including then-outgoing president Barack Obama) in various categories to come up with a composite score, resulting in an overall ranking. Arthur was ranked 35th among all former presidents (down from 32nd in 2009 and 2000). His rankings in the various categories of this most recent poll were as follows: public persuasion (37), crisis leadership (32), economic management (31), moral authority (35), international relations (35), administrative skills (28), relations with congress (29), vision/setting an agenda (34), pursued equal justice for all (27), performance with context of times (32).

Arthur's tepid popularity in life carried over into his assessment by historians, and his reputation after leaving office disappeared. By 1935, historian George F. Howe said that Arthur had achieved "an obscurity in strange contrast to his significant part in American history." By 1975, however, Thomas C. Reeves would write that Arthur's "appointments, if unspectacular, were unusually sound; the corruption and scandal that dominated business and politics of the period did not tarnish his administration." As 2004 biographer Zachary Karabell wrote, although Arthur was "physically stretched and emotionally strained, he strove to do what was right for the country." Indeed, Howe had earlier surmised, "Arthur adopted codefor his own political behavior but subject to three restraints: he remained to everyone a man of his word; he kept scrupulously free from corrupt graft; he maintained a personal dignity, affable and genial though he might be. These restraints ... distinguished him sharply from the stereotype politician." In his final assessment of Arthur, Karabell argues that Arthur lacked the vision or force of character to achieve greatness, but that he deserves credit for presiding over a period of peace and prosperity.

Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Arthur as a below-average president. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Arthur as the 29th best president. A 2017 C-SPAN survey has Chester Arthur ranked among the bottom third of presidents of all time, right below Martin Van Buren and above Herbert Hoover. The survey asked 91 presidential historians to rank the 43 former presidents (including then-outgoing president Barack Obama) in various categories to come up with a composite score, resulting in an overall ranking. Arthur was ranked 35th among all former presidents (down from 32nd in 2009 and 2000). His rankings in the various categories of this most recent poll were as follows: public persuasion (37), crisis leadership (32), economic management (31), moral authority (35), international relations (35), administrative skills (28), relations with congress (29), vision/setting an agenda (34), pursued equal justice for all (27), performance with context of times (32).

Notes

References

Bibliography

Books

* * * * * Graff, Henry F., ed. ''The Presidents: A Reference History'' (3rd ed. 2002)online

* * * * Pletcher, David M. ''The Awkward Years: American Foreign Relations under Garfield and Arthur'' (U of Missouri Press, 1962)

online

* *

Articles

* * * Clary, Zachary. "A Smoking Gun and a Woman’s Touch: President Chester Arthur’s Transformation that Reformed American Politics in the Late Nineteenth Century." ''Penn History Review'' 27.1 (2021): 6+online

* * Gaughan, Anthony J. "Chester Arthur's Ghost: A Cautionary Tale of Campaign Finance Reform." ''Mercer Law Review'' 71 (2019): 779+. * * * * * *

External links

Essays on Chester Arthur and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady

from the

Miller Center of Public Affairs

The Miller Center is a nonpartisan affiliate of the University of Virginia that specializes in United States presidential scholarship, public policy, and political history.

History

The Miller Center was founded in 1975 through the philanthrop ...

Chester Arthur: A Resource Guide

from the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

"Life Portrait of Chester A. Arthur"

from C-SPAN's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', August 6, 1999

"Life and Career of Chester A. Arthur"

presentation by Zachary Karabell at the Kansas City Public Library, May 23, 2012

''Chester A. Arthur's Presidency''

a video by History.com

Chester A. Arthur's Personal Manuscripts

fro

Shapell.org

{{Authority control 1880s in the United States Arthur, Chester A. 1881 establishments in the United States 1885 disestablishments in the United States