Potamopyrgus antipodarum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The New Zealand mud snail (''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'') is a

The shell of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is elongated and has dextral coiling, with 7 to 8 whorls. Between whorls are deep grooves. Shell colors vary from gray and dark brown to light brown. The average height of the shell is approximately 5 mm ( in); maximum size is approximately 12 mm ( in). The snail is usually 4–6 mm in length in the

The shell of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is elongated and has dextral coiling, with 7 to 8 whorls. Between whorls are deep grooves. Shell colors vary from gray and dark brown to light brown. The average height of the shell is approximately 5 mm ( in); maximum size is approximately 12 mm ( in). The snail is usually 4–6 mm in length in the

Northern range expansion and coastal occurrences of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) in the northeast Pacific

'' Aquatic Invasions (2008) Volume 3, Issue 3: 349-353.), most likely due to inadvertent human intervention.

Rapid expansion of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) in the Azov-Black Sea Region

''. Aquatic Invasions (2008) Volume 3, Issue 3: 335-340. Countries where it is found include: *

Present distribution of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' (Gray, 1843) (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in the Slovak Republic

-

First record of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum J.E. Gray 1843 (Mollusca: Hydrobiidae) in Greece – Notes on its population structure and associated microalgae

''. Aquatic Invasions (2008) Volume 3, Issue 3: 341-344

First detected in the

First detected in the

About Microphallus

/ref> In their native habitat, these parasites sterilize many snails, keeping the populations to a manageable size. However, elsewhere in the world in the absence of these parasites, they have become an invasive pest species.

C. Vareille-Morel, ''Resistance of the prosobranch mollusc Potamopyrgus jenkinsi (E.A. Smith, 1889) to decreasing temperatures : an experimental study''; Annls Limnol. Volume 21, Number 3, 1985 ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum''

at

CISR - New Zealand Mud Snail

Center for Invasive Species Research, Summary of New Zealand Mud Snail

Species Profile - New Zealand Mud Snail (''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'')

National Invasive Species Information Center,

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

of very small freshwater snail

Freshwater snails are gastropod mollusks which live in fresh water. There are many different families. They are found throughout the world in various habitats, ranging from ephemeral pools to the largest lakes, and from small seeps and springs ...

with a gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they ar ...

and an operculum. This aquatic gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

is in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Tateidae.

It is native to New Zealand, where it is found throughout the country, but it has been introduced to many other countries, where it is often considered an invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species adv ...

because populations of the snail can reach very high densities.

Shell description

The shell of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is elongated and has dextral coiling, with 7 to 8 whorls. Between whorls are deep grooves. Shell colors vary from gray and dark brown to light brown. The average height of the shell is approximately 5 mm ( in); maximum size is approximately 12 mm ( in). The snail is usually 4–6 mm in length in the

The shell of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is elongated and has dextral coiling, with 7 to 8 whorls. Between whorls are deep grooves. Shell colors vary from gray and dark brown to light brown. The average height of the shell is approximately 5 mm ( in); maximum size is approximately 12 mm ( in). The snail is usually 4–6 mm in length in the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

, but grows to 12 mm in its native range. It is an operculate

The operculum (; ) is a corneous or calcareous anatomical structure like a trapdoor that exists in many (but not all) groups of sea snails and freshwater snails, and also in a few groups of land snails; the structure is found in some marine and ...

snail, with a 'lid' that can seal the opening of its shell. The operculum is thin and corneus with an off-centre nucleus from which paucispiral markings (with few coils) radiate. The aperture

In optics, an aperture is a hole or an opening through which light travels. More specifically, the aperture and focal length of an optical system determine the cone angle of a bundle of rays that come to a focus in the image plane.

An ...

is oval and its height is less than the height of the spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires a ...

. Some morphs, including many from the Great Lakes, exhibit a keel in the middle of each whorl; others, excluding those from the Great Lakes, exhibit periostracal ornamentation such as spines for anti–predator defense.Zaranko, D. T., D. G. Farara and F. G. Thompson. 1997. ''Another exotic mollusk in the Laurentian Great Lakes: the New Zealand native Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray 1843) (Gastropoda, Hydrobiidae)''.Holomuzki, J. R. and B. J. F. Biggs. 2006. ''Habitat–specific variation and performance trade–offs in shell armature of New Zealand mudsnails''. Ecology 87(4):1038–1047.Levri, E.P., A.A. Kelly and E. Love. 2007. ''The invasive New Zealand mud snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) in Lake Erie''. Journal of Great Lakes Research 33: 1–6.

Taxonomy

This species was originally described as ''Amnicola antipodarum'' in 1843 byJohn Edward Gray

John Edward Gray, FRS (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766–1828). The same is used f ...

:

Inhabits New Zealand, in fresh water. Shell ovate, acute, subperforated (generally covered with a black earthy coat); whorls rather rounded, mouth ovate, axis 3 lines; operculum horny and subspiral: variety, spire rather longer, whorls more rounded. This species is like ''Paludina nigra'' of Quoy and Gaimard, but the operculum is more spiral. Quoy described the operculum as concentric, but figured it subspiral. ''Paludina ventricosa'' of Quoy is evidently a Nematura.

Forms

* ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' f. ''carinata'' (J. T. Marshall, 1889)Distribution

This species was originallyendemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

where it lives in freshwater streams and lakes in New Zealand and adjacent small islands.

It has now spread widely and has become naturalised

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

, and an invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species adv ...

in many areas including: Europe (since 1859 in England), Australia, Tasmania, Asia (Japan, in Garmat Ali River in Iraq since 2008), and North America (USA and Canada: Thunder Bay in Ontario since 2001, Washington State since 2002, British Columbia since July 2007''Timothy M. Davidson, Valance E. F. Brenneis, Catherine de Rivera, Robyn Draheim & Graham E. GillespieNorthern range expansion and coastal occurrences of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) in the northeast Pacific

'' Aquatic Invasions (2008) Volume 3, Issue 3: 349-353.), most likely due to inadvertent human intervention.

Invasion in Europe

Since being found in Ireland as early as 1837, ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' has now spread to nearly the whole of Europe. It is considered as about the 42nd worst alien species in Europe and the second worst alien gastropod in Europe. It does not occur in Iceland, Albania, Bulgaria or the former Yugoslavia.Mikhail O. Son.Rapid expansion of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) in the Azov-Black Sea Region

''. Aquatic Invasions (2008) Volume 3, Issue 3: 335-340. Countries where it is found include: *

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

around 1837 Stelfox, A. W. (1926) - probably the first introduction in Europe

* England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

since 1859

* Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

* Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

* Western Baltic Sea since 1887

* Russia

* Azov Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

region, since 1951, Ukraine since 1951 in brackish waters, and since 2005 in freshwater

* Catalonia in Spain, since 1952

* Mediterranean region of France, since the end of 1950s

* Italy, since 1961

* Turkey

* Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

, since September 3, 1981

* Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

, since 1986Čejka T., Dvořák L. & Košel V. 2008Present distribution of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' (Gray, 1843) (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in the Slovak Republic

-

Malacologica Bohemoslovaca

''Malacologica Bohemoslovaca'' is a peer-reviewed open access scientific journal covering all aspects of malacology. It was published by the Slovak Academy of Sciences since 2005. It is published by the Department of Botany and Zoology, Faculty of ...

, 7: 21-25. Online serial at <http://mollusca.sav.sk> ; 25-February-2008.

* Greece, since November 2007Canella Radea, Ioanna Louvrou and Athena Economou-Amilli First record of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum J.E. Gray 1843 (Mollusca: Hydrobiidae) in Greece – Notes on its population structure and associated microalgae

''. Aquatic Invasions (2008) Volume 3, Issue 3: 341-344

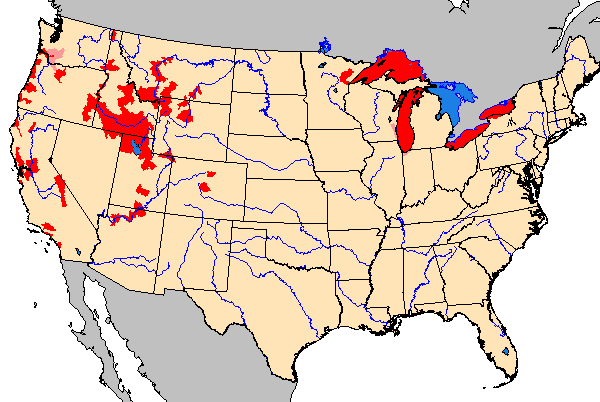

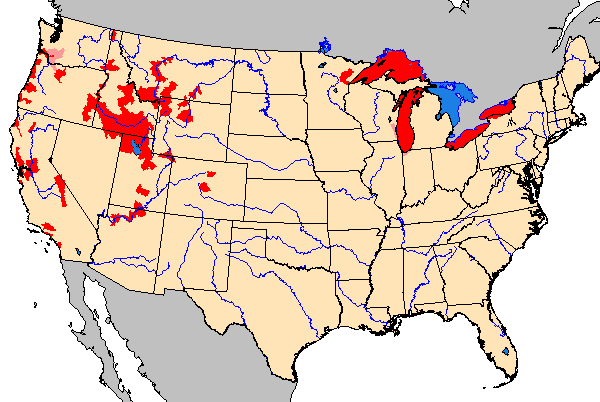

Distribution within the United States

First detected in the

First detected in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

's Snake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

in 1987, the mudsnail has since spread to the Madison River

The Madison River is a headwater tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 183 miles (295 km) long, in Wyoming and Montana. Its confluence with the Jefferson and Gallatin rivers near Three Forks, Montana forms the Missouri River.

Th ...

, Firehole River, and other watercourses around Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowst ...

; samples have been discovered throughout the western United States. Although the exact means of transmission is unknown, it is likely that it was introduced in water transferred with live game fish

Game fish, sport fish or quarry refer to popular fish pursued by recreational anglers, and can be freshwater or saltwater fish. Game fish can be eaten after being caught, or released after capture. Some game fish are also targeted commercial ...

and has been spread by ship ballast or contaminated recreational equipment such as wading gear.

The New Zealand mudsnail has no natural predators or parasites in the United States, and consequently has become an invasive species. Densities have reached greater than 300,000 individuals per m² in the Madison River. It can reach concentrations greater than 500,000 per m², endangering the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

by outcompeting native snails and water insects for food, leading to sharp declines in native populations. Fish populations then suffer because the native snails and insects are their main food source.

Mudsnails are impressively resilient. A snail can live for 24 hours without water. They can however survive for up to 50 days on a damp surface, giving them ample time to be transferred from one body of water to another on fishing gear. The snails may even survive passing through the digestive systems of fish and birds.

Mudsnails have now spread from Idaho to most western states of the U.S., including Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

, California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, and Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

. Environmental officials for these states have attempted to slow the spread of the snail by advising the public to keep an eye out for the snails, and bleach or heat any gear which may contain mudsnails. Rivers have also been temporarily closed to fishing to avoid anglers spreading the snails.

The snails grow to a smaller size in the U.S. than in their native habitat, reaching 6 mm (¼ in) at most in parts of Idaho, but can be much smaller making them easy to overlook when cleaning fishing gear.

Clonal species like the New Zealand mudsnail can often develop clonal lines with quite diverse appearances, called morphs. Until 2005, all the snails found in the western states of the U.S. were believed to be from a single line. However a second morph has been identified in Idaho's Snake River. It grows to a similar size but has a distinctive appearance. (It has been nicknamed the salt-and-pepper mudsnail due to the final whorl being lighter than the rest of the shell.) This morph has apparently been present in the area for several years before being identified correctly as a distinct morph of ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum''. It dominates the typical morph where they overlap, and has a much higher prevalence of males.

In 1991, the New Zealand mudsnail was discovered in Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

, and has now been found in four of the five Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

. In 2005 and 2006, it was found to be widespread in Lake Erie. By 2006 it had spread to Duluth-Superior Harbour and the freshwater estuary of the Saint Louis River. It was found to be inhabiting Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

, after scientists took water samples in early summer of 2008. The snails in the Great Lakes represent a different line from those found in western states, and were probably introduced indirectly through Europe.

In 2002, the New Zealand mudsnail was discovered in the Columbia River Estuary. In 2009, the species was discovered in Capitol Lake

Capitol Lake is a 3 kilometer (1.9 mile) long, artificial lake at the mouth of Deschutes River in Tumwater/Olympia, Washington. The Olympia Brewery sits on Capitol Lake in Tumwater, just downstream from where the Tumwater Falls meet the art ...

in Olympia, Washington. The lake has been closed to all public use, including boating and other recreation, since 2009. A heavy cold snap in 2013, combined with a drawdown in water level in preparation, was roughly estimated to have killed 40–60% of the mudsnail population. Other known locations include the Long Beach peninsula, Kelsey Creek (King County), Thornton Creek (King County), and Lake Washington

Lake Washington is a large freshwater lake adjacent to the city of Seattle.

It is the largest lake in King County and the second largest natural lake in the state of Washington, after Lake Chelan. It borders the cities of Seattle on the west, ...

.

In 2010, the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' reported that the New Zealand mudsnail had infested watersheds in the Santa Monica Mountains

The Santa Monica Mountains is a coastal mountain range in Southern California, next to the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Transverse Ranges. Because of its proximity to densely populated regions, it is one of the most visited natural areas in ...

, posing serious threats to native species and complicating efforts to improve stream-water quality for the endangered Southern California Distinct Population Segment of steelhead

Steelhead, or occasionally steelhead trout, is the common name of the anadromous form of the coastal rainbow trout or redband trout (O. m. gairdneri). Steelhead are native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific basin in Northeast Asia and ...

. According to the article, the snails have expanded "from the first confirmed sample in Medea Creek in Agoura Hills to nearly 30 other stream sites in four years." Researchers at the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission believe that the snails' expansion may have been expedited after the mollusks traveled from stream to stream on the gear of contractors and volunteers.

In Colorado, Boulder Creek and Dry Creek have infestations of New Zealand mudsnails. The snails have been present in Boulder Creek since 2004 and were discovered in Dry Creek in September 2010. Access to both creeks has been closed to help avoid spread of the snails. In the summer of 2015 an industrial-scale wetland rehabilitation project was undertaken in northeast Boulder to rid the area of a mud snail infestation.

Ecology

Habitat

The snail toleratessiltation

Siltation, is water pollution caused by particulate Terrestrial ecoregion, terrestrial Clastic rock, clastic material, with a particle size dominated by silt or clay. It refers both to the increased concentration of suspended sediments and to the ...

, thrives in disturbed watersheds, and benefits from high nutrient flows allowing for filamentous green algae growth. It occurs amongst macrophytes and prefers littoral zones in lakes or slow streams with silt and organic matter substrates, but tolerates high flow environments where it can burrow into the sediment.Collier, K. J., R. J. Wilcock and A. S. Meredith. 1998. ''Influence of substrate type and physico–chemical conditions on macroinvertebrate faunas and biotic indices in some lowland Waikato, New Zealand, streams''. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 32(1):1–19.Holomuzki, J. R. and B. J. F. Biggs. 1999. ''Distributional responses to flow disturbance by a stream–dwelling snail''. Oikos 87(1):36–47.Holomuzki, J. R. and B. J. F. Biggs. 2000. ''Taxon–specific responses to high–flow disturbances in streams: implications for population persistence''. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 19(4):670–679.Negovetic, S. and J. Jokela. 2000. ''Food choice behaviour may promote habitat specificity in mixed populations of clonal and sexual Potamopyrgus antipodarum.'' Experimental Ecology 60(4):435–441.Richards, D. C., L. D. Cazier and G. T. Lester. 2001. ''Spatial distribution of three snail species, including the invader Potamopyrgus antipodarum, in a freshwater spring''. Western North American Naturalist 61(3):375–380.Weatherhead, M. A. and M. R. James. 2001. ''Distribution of macroinvertebrates in relation to physical and biological variables in the littoral zone of nine New Zealand lakes''. Hydrobiologia

''Hydrobiologia'', ''The International Journal of Aquatic Sciences'', is a peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing 21 issues per year, for a total of well over 4000 pages per year. ''Hydrobiologia'' publishes original research, reviews and opi ...

462(1–3):115–129.Death, R. G., B. Baillie and P. Fransen. 2003. ''Effect of Pinus radiata logging on stream invertebrate communities in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand''. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 37(3):507–520.Schreiber, E. S. G., G. P. Quinn and P. S. Lake. 2003. ''Distribution of an alien aquatic snail in relation to flow variability, human activities and water quality''. Freshwater Biology 48(6):951–961.Suren, A. M. 2005. Effects of deposited sediment on patch selection by two grazing stream invertebrates. Hydrobiologia

''Hydrobiologia'', ''The International Journal of Aquatic Sciences'', is a peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing 21 issues per year, for a total of well over 4000 pages per year. ''Hydrobiologia'' publishes original research, reviews and opi ...

549(1):205–218.

In the Great Lakes, the snail reaches densities as high as 5,600 per m² and is found at depths of 4–45 m on a silt and sand substrate.

This species is euryhaline

Euryhaline organisms are able to adapt to a wide range of salinities. An example of a euryhaline fish is the molly (''Poecilia sphenops'') which can live in fresh water, brackish water, or salt water.

The green crab ('' Carcinus maenas'') is an ...

, establishing populations in fresh and brackish water

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

. The optimal salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

is probably near or below 5 ppt, but ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is capable of feeding, growing, and reproducing at salinities of 0–15 ppt and can tolerate 30–35 ppt for short periods of time.Jacobsen, R. and V. E. Forbes. 1997. ''Clonal variation in life–history traits and feeding rates in the gastropod, Potamopyrgus antipodarum: performance across a salinity gradient''. Functional Ecology 11(2):260–267.Leppäkoski, E. and S. Olenin. 2000. ''Non–native species and rates of spread: lessons from the brackish Baltic Sea''. Biological Invasions 2(2):151–163.Costil, K., G.B. J. Dussart and J. Daquzan. 2001. Biodiversity of aquatic gastropods in the Mont St–Michel basin (France) in relation to salinity and drying of habitats. Biodiversity and Conservation 10(1):1–18.Gerard, C., A. Blanc and K. Costil. 2003. ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Mollusca: Hydrobiidae) in continental aquatic gastropod communities: impact of salinity and trematode parasitism''. Hydrobiologia

''Hydrobiologia'', ''The International Journal of Aquatic Sciences'', is a peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing 21 issues per year, for a total of well over 4000 pages per year. ''Hydrobiologia'' publishes original research, reviews and opi ...

493(1–3):167–172.

It tolerates temperatures of 0–34 °C.

Feeding habits

''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is a nocturnal grazer-scraper

Scrape, scraper or scraping may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Abrasion (medical), a type of injury

* Scraper (biology), grazer-scraper, a water animal that feeds on stones and other substrates by grazing algae, microorganism and other matter ...

, feeding on plant and animal detritus

In biology, detritus () is dead particulate organic material, as distinguished from dissolved organic material. Detritus typically includes the bodies or fragments of bodies of dead organisms, and fecal material. Detritus typically hosts comm ...

, epiphytic and periphytic algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

, sediments and diatom

A diatom ( Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising se ...

s.Broekhuizen, N., S. Parkyn and D. Miller. 2001. Fine sediment effects on feeding and growth in the invertebrate grazer Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gastropoda, Hydrobiidae) and Deleatidium sp. (Ephemeroptera, Letpophlebiidae). Hydrobiologia

''Hydrobiologia'', ''The International Journal of Aquatic Sciences'', is a peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing 21 issues per year, for a total of well over 4000 pages per year. ''Hydrobiologia'' publishes original research, reviews and opi ...

457(1–3):125–132.James, M. R., I. Hawes and M. Weatherhead. 2000. ''Removal of settled sediments and periphyton from macrophytes by grazing invertebrates in the littoral zone of a large oligotrophic lake''. Freshwater Biology 44(2):311–326.Kelly, D. J. and I. Hawes. 2005. ''Effects of invasive macrophytes on littoral–zone productivity and foodweb dynamics in a New Zealand high–country lake''. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 24(2):300–320.Parkyn, S. M., J. M. Quinn, T. J. Cox and N. Broekhuizen. 2005. ''Pathways of N and C uptake and transfer in stream food webs: an isotope enrichment experiment''. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 24(4):955–975.

Life cycle

''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' is ovoviviparous and parthenogenic. This means that they can reproduce asexually; females "are born with developing embryos in their reproductive system." Native populations in New Zealand consist ofdiploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectiv ...

sexual and triploid parthenogenically cloned females, as well as sexually functional males (less than 5% of the total population). All introduced populations in North America are clonal, consisting of genetically identical females.

As the snails can reproduce both sexually and asexually, the snail has been used as a model organism for studying the costs and benefits of sexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction allows all members of a population to produce offspring and avoids the costs involved in finding mates. However, asexual offspring are clonal, so lack variation. This makes them susceptible to parasites, as the entire clonal population has the same resistance mechanisms. Once a strain of parasite has overcome these mechanisms, it is able to infect any member of the population. Sexual reproduction mixes up resistance genes through crossing over and the random assortment of gametes in meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately ...

, meaning the members of a sexual population will all have subtly different combinations of resistance genes. This variation in resistance genes means no one parasite strain is able to sweep through the whole population. New Zealand mudsnails are commonly infected with trematode

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as flukes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail. The definitive h ...

parasites, which are particularly abundant in shallow water, but scarce in deeper water. As predicted, sexual reproduction dominates in shallow water, due to its advantages in parasite resistance. Asexual reproduction is dominant in the deeper water of lakes, as the scarcity of parasites means that the advantages of resistance are outweighed by the costs of sexual reproduction.

Each female can produce between 20 and 120 embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

s. The snail produces approximately 230 young per year. Reproduction occurs in spring and summer, and the life cycle is annual.Hall, R. O. Jr., J. L. Tank and M. F. Dybdahl. 2003. Exotic snails dominate nitrogen and carbon cycling in a highly productive stream. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 1(8):407–411.Schreiber, E. S. G., A. Glaister, G. P. Quinn and P. S. Lake. 1998. ''Life history and population dynamics of the exotic snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae) in Lake Purrumbete, Victoria, Australia''. Marine and Freshwater Research 49(1):73–78. The rapid reproduction rate of the snail has caused the numbers of individuals to increase rapidly in new environments. The highest concentration of New Zealand mudsnails ever reported was in Lake Zurich

__NOTOC__

Lake Zurich ( Swiss German/ Alemannic: ''Zürisee''; German: ''Zürichsee''; rm, Lai da Turitg) is a lake in Switzerland, extending southeast of the city of Zürich. Depending on the context, Lake Zurich or ''Zürichsee'' can be used t ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where the species colonized the entire lake within seven years to a density of 800,000 per m².

Parasites

The parasites of this species include at least 11 species of Trematoda. Common parasites of this snail include trematodes of the genus '' Microphallus''./ref> In their native habitat, these parasites sterilize many snails, keeping the populations to a manageable size. However, elsewhere in the world in the absence of these parasites, they have become an invasive pest species.

Other interspecific relationship

''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'' can survive passage through theguts

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

of fish and birds and may be transported by these animals.Aamio, K. and E. Bornsdorff. 1997. ''Passing the gut of juvenile flounder Platichthys flesus (L.) – differential survival of zoobenthic prey species''. Marine Biology 129: 11–14.

It can also float by itself or on mats of '' Cladophora'' spp., and move 60 m upstream in 3 months through positive rheotactic behavior. It can respond to chemical stimuli in the water, including the odor of predatory fish, which causes it to migrate to the undersides of rocks to avoid predation.Levri, E. P. 1998. ''Perceived predation risk, parasitism, and the foraging behavior of a freshwater snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum)''. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76(10):1878–1884.

See also

*Invasive species of New Zealand origin Some species endemic to New Zealand are causing problems in other countries, similar to the way introduced species in New Zealand cause problems for agriculture and indigenous biodiversity.

Animals

*The New Zealand mud snail (''Potamopyrgus antip ...

References

Further reading

* Kerans, B. L, M. F. Dybdahl, M. M. Gangloff and J. E. Jannot. 2005. ''Potamopyrgus antipodarum: distribution, density, and effects on native macroinvertebrate assemblages in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem''. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 24(1):123–138. * Strzelec, M. 2005. ''Impact of the introduced Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gastropods) on the snail fauna in post–industrial ponds in Poland''. Biologia (Bratislava) 60(2):159–163. * de Kluijver, M. J.; Ingalsuo, S. S.; de Bruyne, R. H. (2000). Macrobenthos of the North Sea D-ROM 1. Keys to Mollusca and Brachiopoda. World Biodiversity Database CD-ROM Series. Expert Center for Taxonomic Identification (ETI): Amsterdam, The Netherlands. . 1 cd-rom.External links

C. Vareille-Morel, ''Resistance of the prosobranch mollusc Potamopyrgus jenkinsi (E.A. Smith, 1889) to decreasing temperatures : an experimental study''; Annls Limnol. Volume 21, Number 3, 1985

at

Animalbase AnimalBase is a project brought to life in 2004 and is maintained by the University of Göttingen, Germany. The goal of the AnimalBase project is to digitize early zoological literature, provide copyright-free open access to zoological works, and pr ...

taxonomy, short description, distribution, biology, status (threats), images CISR - New Zealand Mud Snail

Center for Invasive Species Research, Summary of New Zealand Mud Snail

Species Profile - New Zealand Mud Snail (''Potamopyrgus antipodarum'')

National Invasive Species Information Center,

United States National Agricultural Library

The United States National Agricultural Library (NAL) is one of the world's largest agricultural research libraries, and serves as a national library of the United States and as the library of the United States Department of Agriculture. Located ...

. Lists general information and resources for New Zealand Mud Snail.

{{Authority control

Hydrobiidae

Gastropods of New Zealand

Gastropods described in 1843

Taxa named by John Edward Gray