Pope Pius XI and Germany on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the pontificate of

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany. In the dying days of the

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany. In the dying days of the

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies. By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the ''

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies. By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the ''

Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City f ...

(1922–1939), the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

transitioned into Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In 1933, the ailing President von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

as Chancellor of Germany in a Coalition Cabinet, and the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

concluded the Reich concordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

treaty with the still nominally functioning Weimar state later that year. Hoping to secure the rights of the Church in Germany, the Church agreed to a requirement that clergy cease to participate in politics. The Hitler regime routinely violated the treaty, and launched a persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these ter ...

of the Catholic Church in Germany.

Claiming jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, the Nazis interfered with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies, and human rights abuses increased as the Nazis consolidated their power. In 1937, Pius XI issued the ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and st ...

'' encyclical which denounced the regime's breaches of the Concordat, along with the racial and nationalist idolatry which underpinned Nazi ideology

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

. Pius accused the Nazi Government of sowing "fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church", and noted on the horizon the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination over Germany. Following the 1938 ''Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

'' pogrom, Pius joined Western leaders in condemning the pogrom, and antisemitism, sparking protest from the Nazis. Pius XI died in 1939, on the eve of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and was succeeded by his Cardinal Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, who took the name Pius XII, and was to govern the Church through the war, the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

, and the remainder of the Nazi period.

Diplomacy

Reichskonkordat

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany. In the dying days of the

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany. In the dying days of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, the newly appointed Chancellor Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics. Historically, the Church opposed liberal ideas such as democracy, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state und ...

. Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany ...

was dispatched to Rome to negotiate a Reich concordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

with the Holy See. Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's leading experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is pa ...

wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".

On 20 July 1933, the Vatican signed an agreement with Germany, the Reichskonkordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

, partly in an effort to stop Nazi persecution of Catholic institutions.Coppa, p. 132-7Rhodes, p. 182-183 quotation "His contention seemed confirmed in a speech by Staatsminister Wagner in Munich on the 31st March 1934, only nine months after the signature of the Concordat. Wagner said if the Church had not signed a concordat with Germany, the National Socialist government would have abolished the Catholic Youth organisations altogether, and placed them in the same 'anti-state' category as the Marxist groups. ... If the maintenance of Catholic education and of the Catholic Youth associations was, as we have seen often enough before, the principal aim of Papal diplomacy, then his phrase, 'the Concordat prevented greater evils' seems justified. ... The German episcopate considered that neither the Concordats up to then negotiated with individual German States (Lander), nor the Weimar Constitution gave adequate guarantees or assurance to the faithful of respect for their convictions, rights or liberty of action. In such conditions the guarantees could not be secured except through a settlement having the solemn form of a concordat with the central government of the Reich, I would add that since it was the German government which made the proposal, the responsibility for all the regrettable consequences would have fallen on the Holy See if it had refused the proposed Concordat. Although the Church had few illusions about National Socialism, it must be recognized that the Concordat in the years that followed brought some advantages, or at least prevented worse evils. In fact, in spite of all the violations to which it was subjected, it gave German Catholics a juridical basis for their defence, a stronghold behind which to shield themselves in their oppositions to the ever-growing campaign of religious persecution."

The treaty was to be an extension of existing concordats already signed with Prussia and Bavaria. The Bavarian region, the Rhineland and Westphalia as well as parts in southwest Germany, were predominantly Catholic, and the church had previously enjoyed a degree of privilege there. North Germany was heavily Protestant, and Catholics had suffered some discrimination. In the late 1800s, Bismarck's Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church in Germany, Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues wer ...

had been an attempt to almost eliminate Catholic institutions in Germany, or at least their strong connections outside of Germany. With this background, Catholic officials wanted a concordat strongly guaranteeing the church's freedoms. Once Hitler came to power and started enacting laws restricting movement of funds (making it impossible for German Catholics to send money to missionaries, for instance), restricting religious institutions and education, and mandating attendance at Hitler Youth functions (held on Sunday mornings to interfere with Church attendance), the need for a concordat seemed even more urgent to church officials.

The revolution of 1918 and the Weimar constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich (german: Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (''Weimarer Verfassung''), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era (1919–1933). The c ...

of 1919 had thoroughly reformed the former relationship between state and churches. Therefore the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

, represented in Germany by Nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international ...

Eugenio Pacelli

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, the future Pope Pius XII, made unsuccessful attempts to obtain German agreement for such a treaty, and between 1930 and 1933 he attempted to initiate negotiations with representatives of successive German governments.Ludwig Volk ''Das Reichskonkordat vom 20. Juli 1933''. Catholic politicians from the Centre Party repeatedly pushed for a concordat with the new German Republic. In February 1930 Pacelli became the Vatican's Secretary of State, and thus responsible for the Church's foreign policy, and in this position continued to work towards this 'great goal'.

Pius XI was eager to negotiate concordats with any country that was willing to do so, thinking that written treaties were the best way to protect the Church's rights against governments increasingly inclined to interfere in such matters. Twelve concordats were signed during his reign with various types of governments, including some German state governments, and with Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

.

On the level of the states, concordats were achieved with Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

(1924), Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

(1929) and Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden i ...

(1932). On the national level, however, negotiations failed for several reasons: the fragility of the national government; opposition from Socialist and Protestant deputies in the Reichstag; and discord among the German bishops and between them and the Holy See. In particular the questions of denominational schools and pastoral work in the armed forces prevented any agreement on the national level, despite talks in the winter of 1932.

When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

became Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933 and asked for a concordat, Pius XI accepted. Negotiations were conducted on his behalf by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII (1939 – 1958). The Reichskonkordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

was signed by Pacelli and by the German government in June 1933, and included guarantees of liberty for the Church, independence for Catholic organisations and youth groups, and religious teaching in schools.

Negotiations with Hitler

On 30 January 1933,Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

was appointed Chancellor. On 23 March 1933, his government was given dictatorial powers through an Enabling Act

An enabling act is a piece of legislation by which a legislative body grants an entity which depends on it (for authorization or legitimacy) the power to take certain actions. For example, enabling acts often establish government agencies to carr ...

passed by all parties in the Reichstag except the Social Democrats and Communists (whose deputies had already been arrested). Hitler had obtained the votes of the Centre Party, led by Prelate Ludwig Kaas

Ludwig Kaas (23 May 1881 – 15 April 1952) was a German Roman Catholic priest and politician of the Centre Party during the Weimar Republic. He was instrumental in brokering the Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and the German Reich.

E ...

, by issuing oral guarantees of the party's continued existence and the autonomy of the Church and her educational institutions. He also promised good relations with the Holy See, which some interpret as a hint to a future concordat.

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber

Michael Cardinal ''Ritter'' von Faulhaber (5 March 1869 – 12 June 1952) was a German Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Munich for 35 years, from 1917 to his death in 1952. Created Cardinal in 1921, von Faulhaber criticized the Weima ...

wrote to Cardinal Pacelli on 10 April 1933 advising that defending the Jews would be wrong "because that would transform the attack on the Jews into an attack on the Church; and because the Jews are able to look after themselves"."''The Holocaust: What Was Not Said''", Martin Rhonheimer

Martin Rhonheimer (born 1950 in Zurich, Switzerland) is a Swiss political philosophy professor and priest of the Catholic personal prelature Opus Dei. he is teaching professor at the Opus Dei-affiliated Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in ...

, First Things Magazine, November 2003, retrieved 5 July 2009

Hitler met the representative of the German Bishops’ Conference, Bishop Wilhelm Berning of Osnabrück, on 26 April. At the meeting, Hitler declared:

I have been attacked because of my handling of the Jewish question. The Catholic Church considered the Jews pestilent for fifteen hundred years, put them in ghettos, etc., because it recognized the Jews for what they were. In the epoch of liberalism the danger was no longer recognized. I am moving back toward the time in which a fifteen-hundred-year-long tradition was implemented. I do not set race over religion, but I recognize the representatives of this race as pestilent for the state and for the Church, and perhaps I am thereby doing Christianity a great service by pushing them out of schools and public functions.The notes of the meeting do not record any response by Bishop Berning. In the opinion of

Martin Rhonheimer

Martin Rhonheimer (born 1950 in Zurich, Switzerland) is a Swiss political philosophy professor and priest of the Catholic personal prelature Opus Dei. he is teaching professor at the Opus Dei-affiliated Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in ...

"This is hardly surprising: for a Catholic Bishop in 1933 there was really nothing terribly objectionable in this historically correct reminder. And on this occasion, as always, Hitler was concealing his true intentions." In April, Hitler sent his vice chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany ...

, a Catholic nobleman and former member of the Centre Party, to Rome to offer negotiations about a ''Reichskonkordat''. On behalf of Cardinal Pacelli, Ludwig Kaas

Ludwig Kaas (23 May 1881 – 15 April 1952) was a German Roman Catholic priest and politician of the Centre Party during the Weimar Republic. He was instrumental in brokering the Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and the German Reich.

E ...

, the out-going chairman of the Centre Party, negotiated the draft of the terms with Papen. One of Hitler's key conditions for agreeing to the concordat, in violation of earlier promises, had been the dissolution of the Centre Party, which occurred on 5 July.

Shortly before signing the Reichskonkordat on 20 July, Germany signed similar agreements with the major Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

churches in Germany. The concordat was finally signed, by Pacelli for the Vatican and von Papen for Germany, on 20 July. The ''Reichskonkordat'' was ratified on 10 September 1933.

Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the Nazi takeover. The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity and interfered with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies.Theodore S. Hamerow; On the Road to the Wolf's Lair - German Resistance to Hitler; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1997; ; p. 136 The dissolution of theCatholic Centre Party

The Centre Party (german: Zentrum), officially the German Centre Party (german: link=no, Deutsche Zentrumspartei) and also known in English as the Catholic Centre Party, is a Catholic political party in Germany, influential in the German Empire ...

, a former bulwark of the Republic, left modern Germany without a Catholic Party for the first time. Vice Chancellor Papen meanwhile negotiated a Reich Concordat with the Vatican, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics. Hitler, nevertheless, had a "blatant disregard" for the Concordat, wrote Paul O'Shea, and its signing was to him merely a first step in the "gradual suppression of the Catholic Church in Germany". Anton Gill

Anton Gill (born in 1948) is a British writer of historical fiction and nonfiction. He won the H. H. Wingate Award for non-fiction for ''The Journey Back From Hell'', an account of the lives of survivors after their liberation from Nazi concentr ...

wrote that "with his usual irresistible, bullying technique, Hitler then proceeded to take a mile where he had been given an inch" and closed all Catholic institutions whose functions weren't strictly religious:

Almost immediately after signing the Concordat, the Nazis promulgated their Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring – an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Days later, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League.William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; pp. 234–35 Political Catholicism

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics. Historically, the Church opposed liberal ideas such as democracy, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state und ...

was also among the targets of Hitler's 1934 Long Knives purge: the head of Catholic Action, Erich Klausener

Erich Klausener (25 January 1885 – 30 June 1934) was a German Catholic politician and Catholic martyr in the "Night of the Long Knives", a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934, when the Nazi regime carried out a ser ...

, Papen's speech writer and advisor Edgar Jung

Edgar Julius Jung ( pen name: Tyll; 6 March 1894 – 1 July 1934) was a German lawyer born in Ludwigshafen in the Kingdom of Bavaria.

Jung was a leader of the conservative revolutionary movement in Germany which stood not only in opposition to ...

(also a Catholic Action

Catholic Action is the name of groups of lay Catholics who advocate for increased Catholic influence on society. They were especially active in the nineteenth century in historically Catholic countries under anti-clerical regimes such as Spain, I ...

worker); and the national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association, Adalbert Probst. and former Centre Party Chancellor, Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scienti ...

, narrowly escaped execution.Peter Hoffmann; The History of the German Resistance 1933-1945; 3rd Edn (First English Edn); McDonald & Jane's; London; 1977; p 25Lewis, Brenda Ralph (2000); ''Hitler Youth: the Hitlerjugend in War and Peace 1933-1945''; MBI Publishing; ; p. 45

Clergy, religious sisters

A religious sister (abbreviated ''Sr.'' or Sist.) in the Catholic Church is a woman who has taken public vows in a religious institute dedicated to apostolic works, as distinguished from a nun who lives a cloistered monastic life dedicated to pra ...

, and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality". Priests were watched closely and frequently denounced, arrested and sent to concentration camps.Paul Berben; Dachau: The Official History 1933–1945; Norfolk Press; London; 1975; ; p. 142 After constant confrontations, by late 1935 Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen

Clemens Augustinus Emmanuel Joseph Pius Anthonius Hubertus Marie Graf von Galen (16 March 1878 – 22 March 1946), better known as ''Clemens August Graf von Galen'', was a German count, Bishop of Münster, and cardinal of the Catholic Church ...

of Münster was urging a joint pastoral letter protesting an "underground war" against the church. In his history of the German Resistance, Hoffmann writes that, from the beginning:

Encyclicals

Pius XI saw the rising tide of totalitarianism with alarm and delivered three papal encyclicals challenging the new creeds: against Italian Fascism ''Non abbiamo bisogno

''Non abbiamo bisogno'' (Italian for "We do not need") is a Roman Catholic encyclical published on 29 June 1931 by Pope Pius XI.

Context

The encyclical condemned Italian fascism's “pagan worship of the State” (statolatry) and “revolutio ...

'' (1931; "We Do Not Need to Acquaint You"); against Nazism ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and st ...

'' (1937; "With Deep Anxiety"); and against atheistic Communism ''Divini redemptoris

''Divini Redemptoris'' (Latin for the promise of a Divine Redeemer) is an anti-communist encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI. It was published on 19 March 1937. In this encyclical, the pope sets out to "expose once more in a brief synthesis the pr ...

'' (1937; "Divine Redeemer"). He also challenged the extremist nationalism of the Action Francaise movement and anti-semitism in the United States. ''Non abbiamo bisogno'' condemned Italian fascism’s "pagan worship of the State" and "revolution which snatches the young from the Church and from Jesus Christ, and which inculcates in its own young people hatred, violence and irreverence."

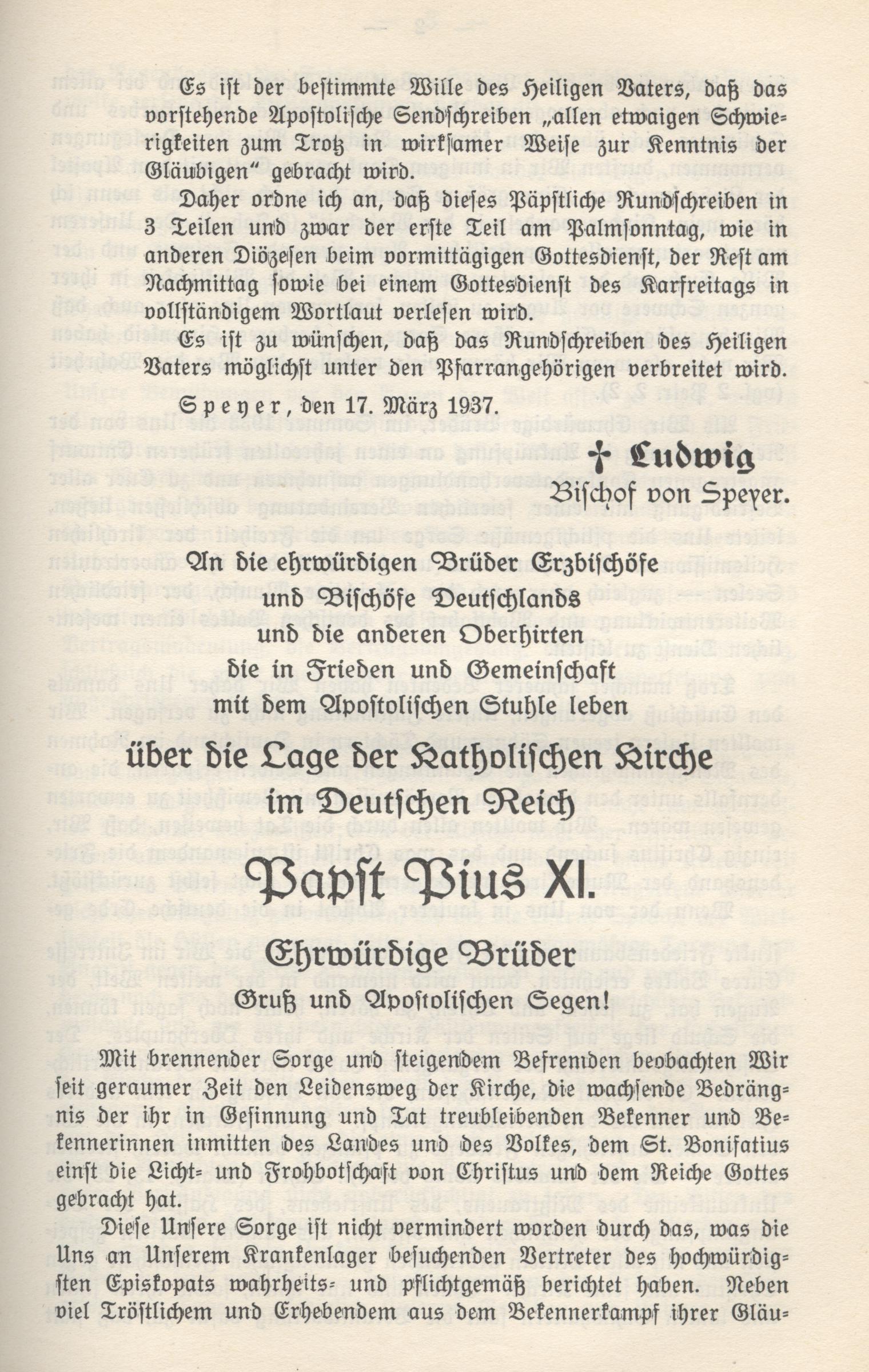

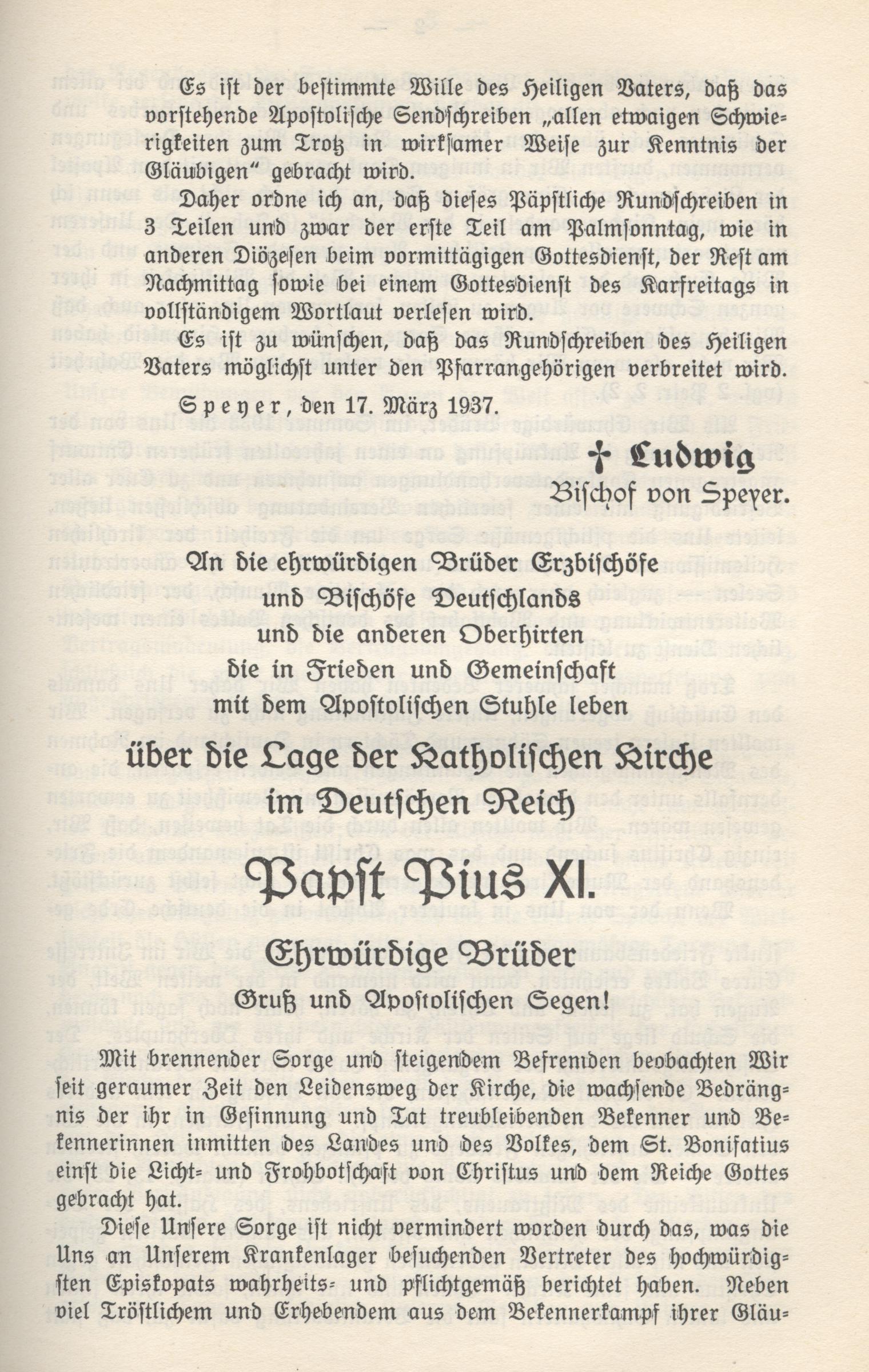

''Mit brennender Sorge''

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies. By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the ''

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies. By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and st ...

'' encyclical – accusing the Nazi Government of violations of the 1933 Concordat, and further that it was sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church". The Pope noted on the horizon the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination over Germany. He asserted the inviolability of human rights and expressed deep concern at the Nazi regime's flouting of the 1933 Concordat, its treatment of Catholics and abuse of Christian values.Anton Gill

Anton Gill (born in 1948) is a British writer of historical fiction and nonfiction. He won the H. H. Wingate Award for non-fiction for ''The Journey Back From Hell'', an account of the lives of survivors after their liberation from Nazi concentr ...

; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; p.58

Copies had to be smuggled into Germany so they could be read from the pulpit

The encyclical, the only one ever written in German, was addressed to German bishops and was read in all parishes of Germany. The actual writing of the text is credited to Munich Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber

Michael Cardinal ''Ritter'' von Faulhaber (5 March 1869 – 12 June 1952) was a German Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Munich for 35 years, from 1917 to his death in 1952. Created Cardinal in 1921, von Faulhaber criticized the Weima ...

and to the Cardinal Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, who later became Pope Pius XII.

Nazi violations of the Reichskonkordat had escalated to include physical violence.Rhodes, p. 197 quotation "Violence had been used against a Catholic leader as early as June 1934, in the 'Night of the Long Knives' ... by the end of 1936 physical violence was being used openly and blatantly against the Catholic Church. The real issue was not, as the Nazis contended, a struggle with 'political Catholicism', but that the regime would tolerate the Church only if it adapted its religious and moral teaching to the materialist dogma of blood and race - that is, if it ceased to be Christian."Shirer, p. 235 quotation "On July 25, five days after the ratification of the concordat, the German government promulgated a sterilization law, which particularly offended the Catholic Church. Five days later the first steps were taken to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. During the next years, thousands of Catholic priests, nuns and lay leaders were arrested, many of them on trumped-up charges of 'immorality' or 'smuggling foreign currency'. Erich Klausener, leader of Catholic Action, was, as we have seen, murdered in the June 30, 1934, purge. Scores of Catholic publications were suppressed, and even the sanctity of the confessional was violated by Gestapo agents. By the spring of 1937, the Catholic hierarchy, in Germany, which, like most of the Protestant clergy, had tried to co-operate with the new regime, was thoroughly disillusioned.McGonigle, p. 172 quotation "Hitler, of course flagrantly violated the rights of Catholics and others whenever it pleased him. Catholic Action groups were attacked by Hitler's police and Catholic schools were closed. Priests were persecuted and sent to concentration camps. ... On Palm Sunday, 21 March 1937, the encyclical ''Mit Brennender Sorge'' was read in Catholic Churches in Germany. In effect it taught that the racial ideas of the leader ''(fuhrer)'' and totalitarianism stood in opposition to the Catholic faith. The letter let the world, and especially German Catholics, know clearly that the Church was harassed and persecuted, and that it clearly opposed the doctrines of Nazism." Drafted by the future Pope Pius XIIPham, p. 45, quotation: "When Pius XI was complimented on the publication, in 1937, of his encyclical denouncing Nazism, ''Mit Brennender Sorge'', his response was to point to his Secretary of State and say bluntly, 'The credit is his.'" and read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches, it criticized HitlerVidmar, p. 327 quotation "Pius XI's greatest coup was in writing the encyclical ''Mit Brennender Sorge'' ("With Burning Desire") in 1936, and having it distributed secretly and ingeniously by an army of motorcyclists, and read from the pulpit on Palm Sunday before the Nazis obtained a single copy. It stated (in German and not in the traditional Latin) that the Concordat with the Nazis was agreed to despite serious misgivings about Nazi integrity. It then went on to condemn the persecution of the church, the neopaganism of the Nazi ideology-especially its theory of racial superiority-and Hitler himself, calling him 'a mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance.'" and condemned Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

persecution and ideology and has been characterized by scholars as the "first great official public document to dare to confront and criticize Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

" and "one of the greatest such condemnations ever issued by the Vatican."Bokenkotter, pp. 389–392, quotation "And when Hitler showed increasing belligerence toward the Church, Pius met the challenge with a decisiveness that astonished the world. His encyclical ''Mit Brennender Sorge'' was the 'first great official public document to dare to confront and criticize Nazism' and 'one of the greatest such condemnations ever issued by the Vatican.' Smuggled into Germany, it was read from all the Catholic pulpits on Palm Sunday in March 1937. It denounced the Nazi "myth of blood and soil" and decried its neopaganism, its war of annihilation against the Church, and even described the Fuhrer himself as a 'mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance'. The Nazis were infuriated, and in retaliation closed and sealed all the presses that had printed it and took numerous vindictive measures against the Church, including staging a long series of immorality trials of Catholic clergy."Rhodes, p. 204-205 quotation "''Mit brennender Sorge'' did not prevaricate. Although it began mildly enough with an account of the broad aims of the Church, it went on to become one of the greatest condemnations of a national regime ever pronounced by the Vatican. Its vigorous language is in sharp contrast to the involved style in which encyclicals were normally written. The education question was fully and critically examined, and a long section devoted to disproving the Nazi theory of Blood and Soil (Blut und Boden) and the Nazi claim that faith in Germany was equivalent to faith in God. There were scathing references to Rosenberg's ''Myth of the Twentieth Century'' and its neo-paganism. The pressure exercised by the Nazi party on Catholic officials to betray their faith was lambasted as 'base, illegal and inhuman'. The document spoke of "a condition of spiritual oppression in Germany such as has never been seen before", of 'the open fight against the Confessional schools and the suppression of liberty of choice for those who desire a Catholic education'. 'With pressure veiled and open,' it went on, 'with intimidation, with promises of economic, professional, civil, and other advantages, the attachment of Catholics to the Faith, particularly those in government employment, is exposed to a violence as illegal as it is inhuman.' 'The calvary of the Church': 'The war of annihilation against the Catholic Faith'; 'The cult of idols'. The fulminations thundered down from the pulpits to the delighted congregations. Nor was the Fuhrer himself spared, for his 'aspirations to divinity', 'placing himself on the same level as Christ': 'a mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance' (widerliche Hochmut)."Norman, p. 167 quotation "But violations began almost at once by Nazi Party officials, and in 1937 the papacy issued a Letter to the German bishops to be read in the churches. ''Mit Brennender Sorge'' ... denounced the violations as contrary to Natural Law and to the term of the Concordat. The Letter, in fact, amounted to a condemnation of Nazi ideology: 'In political life within the state, since it confuses considerations of utility with those of right, it mistakes the basic fact than man as a person possesses God-given rights which must be preserved from all attacks aimed at denying, suppressing, or disregarding them.' The Letter also rejected absolutely the concept of a German National Church." This encyclical condemned particularly the paganism of Nazi ideology, the myth of race and blood, and fallacies in the Nazi conception of God:

The Nazis responded with, an intensification of their campaign against the churches, beginning around April.Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.381-382 There were mass arrests of clergy and church presses were expropriated.

Impact and consequences

According toEamon Duffy

Eamon Duffy (born 1947) is an Irish historian. He is a professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow and former president of Magdalene College.

Early life

Duffy was born on 9 February 1947, in Dundalk, I ...

, "The impact of the encyclical was immense" and the "infuriated" Nazis increased their persecution of Catholics and the Church by initiating a "long series" of persecutions of clergy and other measures.Courtois, p. 29Duffy, (paperback edition) p. 343 quotation "In a triumphant security operation, the encyclical was smuggled into Germany, locally printed, and read from Catholic pulpits on Palm Sunday 1937. ''Mit Brennender Sorge'' ('With Burning Anxiety') denounced both specific government actions against the Church in breach of the concordat and Nazi racial theory more generally. There was a striking and deliberate emphasis on the permanent validity of the Jewish scriptures, and the Pope denounced the 'idolatrous cult' which replaced belief in the true God with a 'national religion' and the 'myth of race and blood'. He contrasted this perverted ideology with the teaching of the Church in which there was a home 'for all peoples and all nations'. The impact of the encyclical was immense, and it dispelled at once all suspicion of a Fascist Pope. While the world was still reacting, however, Pius issued five days later another encyclical, ''Divini Redemptoris'' denouncing Communism, declaring its principles 'intrinsically hostile to religion in any form whatever', detailing the attacks on the Church which had followed the establishment of Communist regimes in Russia, Mexico and Spain, and calling for the implementation of Catholic social teaching to offset both Communism and 'amoral liberalism'. The language of ''Divini Redemptoris'' was stronger than that of ''Mit Brennender Sorge'', its condemnation of Communism even more absolute than the attack on Nazism. The difference in tone undoubtedly reflected the Pope's own loathing of Communism as the ultimate enemy. The last year of his life, however, left no one any doubt of his total repudiation of the right-wing tyrannies in Germany and, despite his instinctive sympathy with some aspects of Fascism, increasingly in Italy also. His speeches and conversations were blunt, filled with phrases like 'stupid racialism', 'barbaric Hitlerism'."

Gerald Fogarty wrote that "in the end, the encyclical had little positive effect, and if anything only exacerbated the crisis." The American ambassador reported that it "had helped the Catholic Church in Germany very little but on the contrary has provoked the Nazi state ... to continue its oblique assault upon Catholic institutions." Frank J. Coppa wrote that the encyclical was viewed by the Nazis as "a call to battle against the Reich" and that Hitler was furious and "vowed revenge against the Church".

The German police confiscated as many copies as they could and called it "high treason". According to John Vidmar John C. Vidmar, O.P. is an associate professor of history at Providence College, Rhode Island where he also serves as provincial archivist and teaches history. Prior to his work at Providence, he served as associate professor, academic dean, acting ...

, Nazi reprisals against the Church in Germany followed thereafter, including "staged prosecutions of monks for homosexuality, with the maximum of publicity".Vidmar, p. 254. According to Thomas Bokenkotter, "the Nazis were infuriated, and in retaliation closed and sealed all the presses that had printed it and took numerous vindictive measures against the Church, including staging a long series of immorality trials of the Catholic clergy." According to Eamon Duffy

Eamon Duffy (born 1947) is an Irish historian. He is a professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow and former president of Magdalene College.

Early life

Duffy was born on 9 February 1947, in Dundalk, I ...

"The impact of the encyclical was immense, and it dispelled at once all suspicion of a Fascist Pope." According to Owen Chadwick

William Owen Chadwick (20 May 1916 – 17 July 2015) was a British Anglican priest, academic, rugby international,Chadwick, Owen pp. 254–255.

While numerous German Catholics who participated in the secret printing and distribution of ''

papal encyclical of

;

/ref> His first encyclical ''

Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and st ...

'' went to jail and concentration camps, the press in the Western democracies remained silent, which Pius XI called as "a conspiracy of silence".Franzen, 395 The pope left Rome to avoid meeting Hitler during the dictator's state visit to Italy in May 1938, denounced the display of Swastika flags in Rome, and closed the Vatican museums.

Teachings against Nazi antisemitism

As the extreme nature of Nazi racialantisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

became obvious, and as Mussolini in the late 1930s began imitating Hitler's anti-Jewish race laws in Italy, Pius XI was perturbed. In the 1930s, he urged Mussolini to ask Hitler to restrain the anti-Semitic actions taking place in Germany. When the newly installed Nazi Government began to instigate its program of antisemitism, Pope Pius ordered the Papal Nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo

Cesare Vincenzo Orsenigo (December 13, 1873 – April 1, 1946) was Apostolic Nuncio to Germany from 1930 to 1945, during the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II. Along with the German ambassador to the Vatican, Diego von Bergen and later Ernst v ...

, to "look into whether and how it may be possible to become involved" in their aid. Orsenigo proved a poor instrument in this regard, concerned more with the anti-church policies of the Nazis and how these might effect German Catholics, than with taking action to help German Jews.

In 1937, he issued the ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and st ...

'' (german: "With burning concern") encyclical, in which he asserted the inviolability of human rights. It was written partly in response to the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

, and condemned racial theories and the mistreatment of people based on race. It repudiated Nazi racial theory and the "so-called myth of race and blood". It denounced "whoever exalts race, or the people, or the State ... above their standard value and divinizes them to an idolatrous level"; spoke of divine values independent of "space country and race" and a Church for "all races"; and said, "None but superficial minds could stumble into concepts of a national God, of a national religion; or attempt to lock within the frontiers of a single people, within the narrow limits of a single race, God, the Creator of the universe.''Mit Brennender Sorge''papal encyclical of

Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City f ...

The document noted on the horizon over Germany the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination.

Following the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

and the extension of antisemitic laws in Germany, Jewish refugees sought sanctuary outside the Reich. In Rome, Pius XI told a group of Belgian pilgrims on 6 September 1938 that it was not possible for Christians to participate in anti-Semitism: "Mark well that in the Catholic Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different eleme ...

, Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

is our Patriarch and forefather. Anti-Semitism is incompatible with the lofty thought which that fact expresses. It is a movement with which we Christians can have nothing to do. No, no, I say to you it is impossible for a Christian to take part in anti-Semitism. It is inadmissible. Through Christ and in Christ we are the spiritual progeny of Abraham. Spiritually, we hristiansare all Semites." These comments were subsequently published worldwide but had little resonance at the time in the secular media.

On 11 November 1938, following ''Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

'', Pope Pius XI joined Western leaders in condemning the pogrom. In response, the Nazis organised mass demonstrations against Catholics and Jews in Munich, and the Bavarian Gauleiter Adolf Wagner

Adolf Wagner (1 October 1890 – 12 April 1944) was a Nazi Party official and politician who served as the Party's ''Gauleiter'' in Munich and as the powerful Interior Minister of Bavaria throughout most of the Third Reich.

Early years

Born in ...

declared before 5,000 protesters: "Every utterance the Pope makes in Rome is an incitement of the Jews throughout the world to agitate against Germany." On 21 November, in an address to the world's Catholics, the Pope rejected the Nazi claim of racial superiority, and insisted instead that there was only a single human race. Robert Ley

Robert Ley (; 15 February 1890 – 25 October 1945) was a German politician and labour union leader during the Nazi era; Ley headed the German Labour Front from 1933 to 1945. He also held many other high positions in the Party, including ''Gaul ...

, the Nazi Minister of Labour, declared the following day in Vienna: "No compassion will be tolerated for the Jews. We deny the Pope's statement that there is but one human race. The Jews are parasites." Catholic leaders including Cardinal Schuster of Milan, Cardinal van Roey in Belgium and Cardinal Verdier in Paris backed the Pope's strong condemnation of Kristallnacht.

Pius XI's Secretary of State, Cardinal Pacelli, made some 55 protests against Nazi policies, including its "ideology of race".''Hitler's Pope?'';

Martin Gilbert

Sir Martin John Gilbert (25 October 1936 – 3 February 2015) was a British historian and honorary Fellow of Merton College, Oxford. He was the author of eighty-eight books, including works on Winston Churchill, the 20th century, and Jewish h ...

; The American Spectator; 18/8/06 Pacelli succeeded Pius XI on the eve of war in 1939. Taking the name Pius XII, he also employed diplomacy to aid the victims of Nazi persecution, and directed his Church to provide discreet aid to Jews.Encyclopædia Britannica : ''Reflections on the Holocaust''/ref> His first encyclical ''

Summi Pontificatus

''Summi Pontificatus'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XII published on 20 October 1939. The encyclical is subtitled "on the unity of human society". It was the first encyclical of Pius XII and was seen as setting "a tone" for his papacy. It c ...

'' again spoke against racism, with specific reference to Jews: "there is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision."Pius XII, ''Summi Pontificatus''; 48; October 1939Assessment

Peter Kent writes:Peter Kent, p. 601By the time of his death ... Pius XI had managed to orchestrate a swelling chorus of Church protests against the racial legislation and the ties that bound Italy to Germany. He had single-mindedly continued to denounce the evils of the nazi regime at every possible opportunity and feared above all else the re-opening of the rift between Church and State in his beloved Italy. He had, however, few tangible successes. There had been little improvement in the position of the Church in Germany and there was growing hostility to the Church in Italy on the part of the fascist regime. Almost the only positive result of the last years of his pontificate was a closer relationship with the liberal democracies and yet, even this was seen by many as representing a highly partisan stance on the part of the Pope. In the age of appeasement, the pugnacious obstinacy of Pius XI was held to be contributing more to the polarization of Europe than to its pacification.

See also

*Catholic Church and Nazi Germany

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the no ...

* Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany

References

{{reflist Pope Pius XI Foreign relations of Nazi Germany Nazi Germany and Catholicism Germany–Holy See relations