Pompey the Great on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

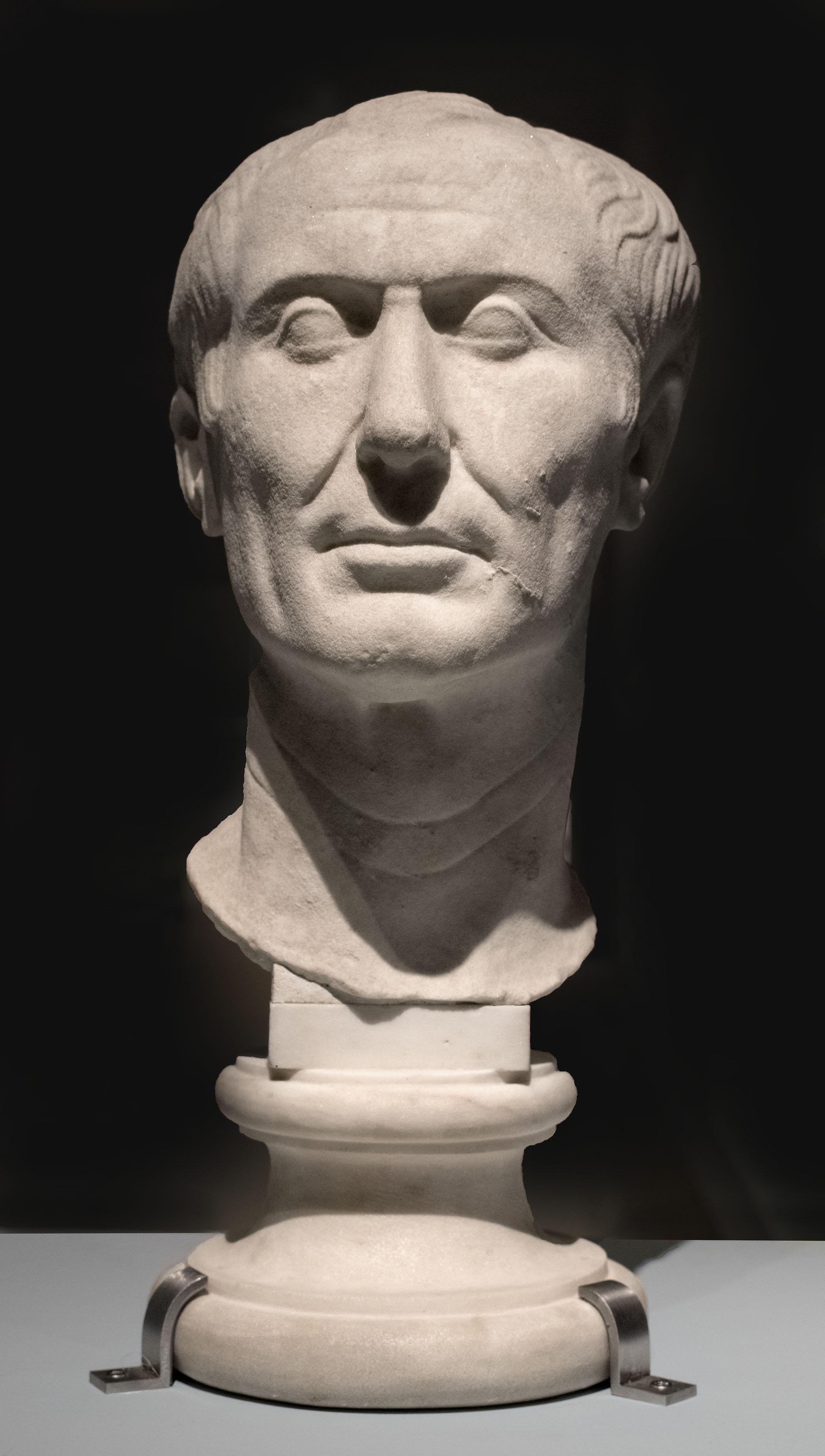

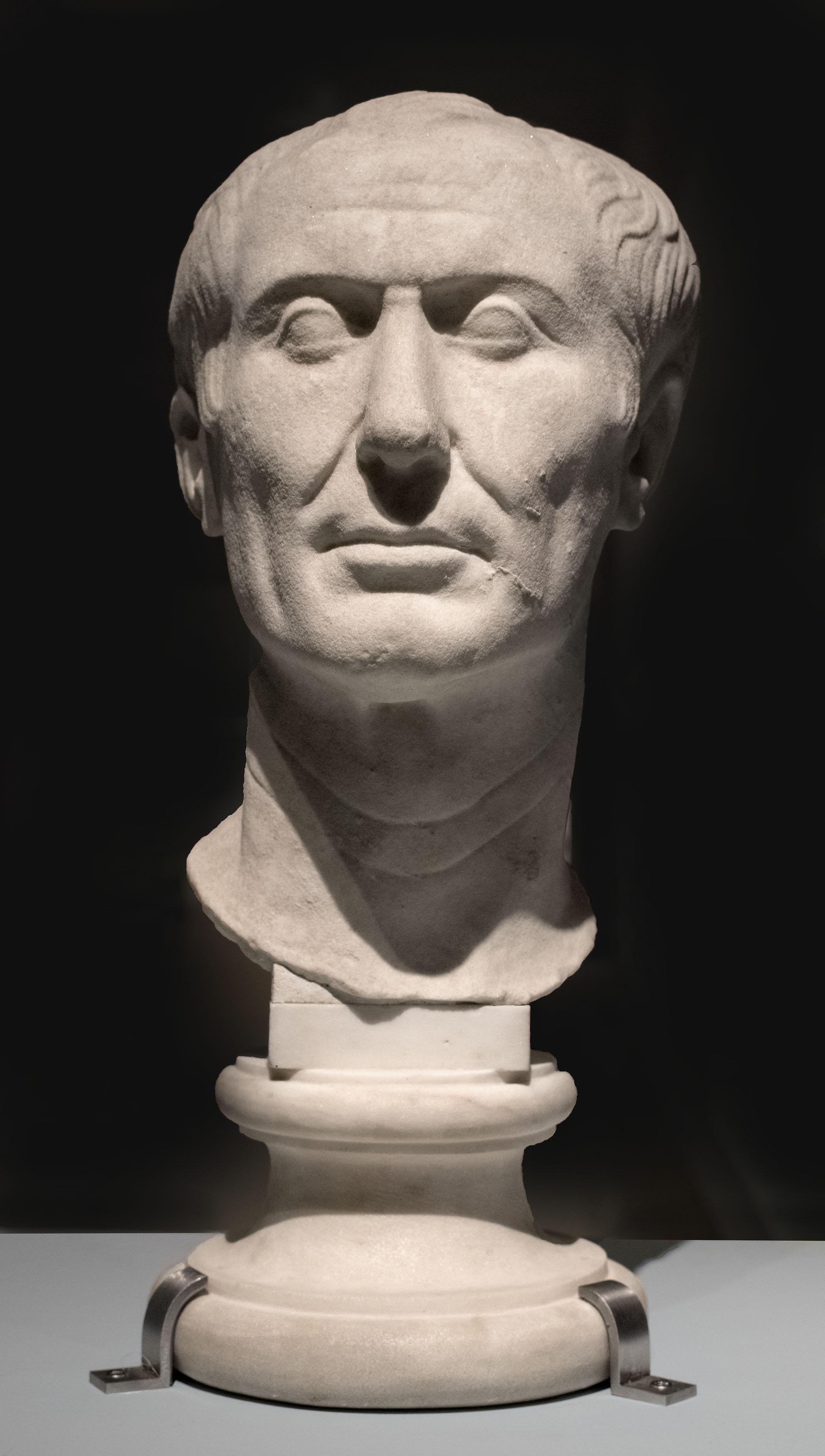

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading

Pompey's father acquired a reputation for greed, political double-dealing, and military ruthlessness. He fought the Social War against Rome's Italian allies, and was granted a

Pompey's father acquired a reputation for greed, political double-dealing, and military ruthlessness. He fought the Social War against Rome's Italian allies, and was granted a  Pompey served under his father's command during the final years of the Social War. When his father died, Pompey was put on trial due to accusations that his father stole public property. As his father's heir, Pompey could be held to account. He discovered that the theft was committed by one of his father's freedmen. Following his preliminary bouts with his accuser, the judge took a liking to Pompey and offered his daughter Antistia in marriage, and so Pompey was acquitted.

Another

Pompey served under his father's command during the final years of the Social War. When his father died, Pompey was put on trial due to accusations that his father stole public property. As his father's heir, Pompey could be held to account. He discovered that the theft was committed by one of his father's freedmen. Following his preliminary bouts with his accuser, the judge took a liking to Pompey and offered his daughter Antistia in marriage, and so Pompey was acquitted.

Another

After Sulla's death in 78 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus tried to revive the fortunes of the ''populares''. He became the new leader of the reformist movement silenced by Sulla. He tried to prevent Sulla from receiving a state funeral and from having his body buried in the Campus Martius. Pompey opposed this and ensured Sulla's burial with honours. In 77 BC, when Lepidus had left for his

After Sulla's death in 78 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus tried to revive the fortunes of the ''populares''. He became the new leader of the reformist movement silenced by Sulla. He tried to prevent Sulla from receiving a state funeral and from having his body buried in the Campus Martius. Pompey opposed this and ensured Sulla's burial with honours. In 77 BC, when Lepidus had left for his

Piracy in the Mediterranean became a large-scale problem, with a big network of pirates coordinating operations over wide areas with many fleets. According to Cassius Dio, the many years of war contributed to this, as a large number of fugitives joined them, since pirates were more difficult to catch or break up than bandits. The pirates pillaged coastal fields and towns. Rome was affected through shortages of imports and the supply of grains, but the Romans did not pay proper attention to the problem. They sent out fleets when "they were stirred by individual reports" and these did not achieve anything. Cassius Dio wrote that these operations caused greater distress for Rome's allies. It was thought that a war against the pirates would be big and expensive, and that it was impossible to attack or drive back all the pirates at once. As not much was done against them, some towns were turned into pirate winter quarters and raids further inland were carried out. Many pirates settled on land in various places and relied on an informal network of mutual assistance. Towns in Italy were also attacked, including Ostia, the port of Rome, with ships burned and pillaged. The pirates seized important Romans and demanded large ransoms.

Piracy in the Mediterranean became a large-scale problem, with a big network of pirates coordinating operations over wide areas with many fleets. According to Cassius Dio, the many years of war contributed to this, as a large number of fugitives joined them, since pirates were more difficult to catch or break up than bandits. The pirates pillaged coastal fields and towns. Rome was affected through shortages of imports and the supply of grains, but the Romans did not pay proper attention to the problem. They sent out fleets when "they were stirred by individual reports" and these did not achieve anything. Cassius Dio wrote that these operations caused greater distress for Rome's allies. It was thought that a war against the pirates would be big and expensive, and that it was impossible to attack or drive back all the pirates at once. As not much was done against them, some towns were turned into pirate winter quarters and raids further inland were carried out. Many pirates settled on land in various places and relied on an informal network of mutual assistance. Towns in Italy were also attacked, including Ostia, the port of Rome, with ships burned and pillaged. The pirates seized important Romans and demanded large ransoms.

In Plutarch's account, Pompey's scattered forces encompassed every pirate fleet they came across and brought them to port, the remaining pirates escaping to Cilicia. Pompey attacked Cilicia with his sixty best ships; after that, he cleared the

In Plutarch's account, Pompey's scattered forces encompassed every pirate fleet they came across and brought them to port, the remaining pirates escaping to Cilicia. Pompey attacked Cilicia with his sixty best ships; after that, he cleared the

Lucius Licinius Lucullus was conducting the

Lucius Licinius Lucullus was conducting the  Cassius Dio wrote that Mithridates kept withdrawing because his forces were inferior. Pompey entered

Cassius Dio wrote that Mithridates kept withdrawing because his forces were inferior. Pompey entered

A conflict between the brothers

A conflict between the brothers

Pompey set out to liberate a number of Hellenised towns from their rulers. He joined seven towns east of the

Pompey set out to liberate a number of Hellenised towns from their rulers. He joined seven towns east of the

In the Senate, Pompey was probably equally admired and feared. On the streets, he was as popular as ever. His eastern victories earned him his third triumph, which he celebrated on his 45th birthday in 61 BC,Pliny, ''Natural History'', 37.6 seven months after his return to Italy. Plutarch wrote that it surpassed all previous triumphs, taking place over an unprecedented two days. Much of what had been prepared would not find a place and would have been enough for another procession. Inscriptions carried in front of the procession indicated the nations he defeated (

In the Senate, Pompey was probably equally admired and feared. On the streets, he was as popular as ever. His eastern victories earned him his third triumph, which he celebrated on his 45th birthday in 61 BC,Pliny, ''Natural History'', 37.6 seven months after his return to Italy. Plutarch wrote that it surpassed all previous triumphs, taking place over an unprecedented two days. Much of what had been prepared would not find a place and would have been enough for another procession. Inscriptions carried in front of the procession indicated the nations he defeated (

When Pompey returned to Rome from the

When Pompey returned to Rome from the

In 54 BC, Pompey was the only member of the triumvirate who was in Rome. Caesar continued his campaigns in Gaul and Crassus undertook his campaign against the Parthians. In September 54 BC, Julia, the daughter of Caesar and wife of Pompey, died while giving birth to a girl, who also died a few days later. Plutarch wrote that Caesar felt that this was the end of his good relationship with Pompey. The news created factional discord and unrest in Rome as it was thought that the death brought the end of the ties between Caesar and Pompey. The campaign of Crassus against Parthia was disastrous. Shortly after the death of Julia, Crassus died at the

In 54 BC, Pompey was the only member of the triumvirate who was in Rome. Caesar continued his campaigns in Gaul and Crassus undertook his campaign against the Parthians. In September 54 BC, Julia, the daughter of Caesar and wife of Pompey, died while giving birth to a girl, who also died a few days later. Plutarch wrote that Caesar felt that this was the end of his good relationship with Pompey. The news created factional discord and unrest in Rome as it was thought that the death brought the end of the ties between Caesar and Pompey. The campaign of Crassus against Parthia was disastrous. Shortly after the death of Julia, Crassus died at the

Caesar sent a detachment to Ariminum (

Caesar sent a detachment to Ariminum ( Caesar pursued Pompey to prevent him from gathering other forces to renew the war. Pompey had stopped at Amphipolis, where he held a meeting with friends to collect money. An edict was issued in his name that all the youth of the province of Macedonia (i.e. Greece), whether Greeks or Romans, were to take an oath. It was not clear whether Pompey wanted new levies to fight or whether this was concealment of a planned escape.

When he heard that Caesar was approaching, Pompey left and went to

Caesar pursued Pompey to prevent him from gathering other forces to renew the war. Pompey had stopped at Amphipolis, where he held a meeting with friends to collect money. An edict was issued in his name that all the youth of the province of Macedonia (i.e. Greece), whether Greeks or Romans, were to take an oath. It was not clear whether Pompey wanted new levies to fight or whether this was concealment of a planned escape.

When he heard that Caesar was approaching, Pompey left and went to  On 28 September, Achillas went to Pompey's ship on a fishing boat together with

On 28 September, Achillas went to Pompey's ship on a fishing boat together with

For the historians of his own and later Roman periods, Pompey fit the

For the historians of his own and later Roman periods, Pompey fit the

Accessed August 2016 * Appian. (2014). ''The Foreign Wars, Book 12, The Mithridatic Wars''. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Accessed August 2016 * Julius Caesar. (1976). ''The Civil War: Together with the Alexandrian War, the African War, and the Spanish War.'' Penguin Classics. New impression edition.

Accessed August 2016 * Cassius Dio. (1989). ''Roman History''. Volume 3, Books 36–40. (Loeb Classical Library) Loeb New issue of 1916 edition. ; Vol. 4, Books 41–45,

Books 36–41. Accessed August 2016 * Josephus. (2014). ''The Antiquities of the Jews'': Volume II (Books XI–XX). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; First edition.

Accessed August 2016 * Plutarch. (1917). ''Lives, Vol V: Agesilaus and Pompey. Pelopidas and Marcellus''. (Loeb Classical Library). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey

Accessed August 2016

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of Rome from republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

to empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

. He was (for a time) a student of Roman general Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had t ...

as well as the political ally, and later enemy, of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

.

A member of the senatorial nobility, Pompey entered into a military career while still young. He rose to prominence serving the dictator Sulla as a commander in the civil war of 83–82 BC. Pompey's success as a general while young enabled him to advance directly to his first Roman consul

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the ''cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which politic ...

ship without following the traditional ''cursus honorum

The ''cursus honorum'' (; , or more colloquially 'ladder of offices') was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The ''c ...

'' (the required steps to advance in a political career). He was elected as Roman consul on three occasions. He celebrated three Roman triumph

The Roman triumph (') was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or in some historical tra ...

s, served as a commander in the Sertorian War

The Sertorian War was a civil war fought from 80 to 72 BC between a faction of Roman rebels ( Sertorians) and the government in Rome (Sullans). The war was fought on the Iberian Peninsula (called ''Hispania'' by the Romans) and was one of the ...

, the Third Servile War

The Third Servile War, also called the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus by Plutarch, was the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic known as the Servile Wars. This third rebellion was the only one that directly ...

, the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of th ...

, and in various other military campaigns. Pompey's early success earned him the cognomen

A ''cognomen'' (; plural ''cognomina''; from ''con-'' "together with" and ''(g)nomen'' "name") was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became here ...

''Magnus

Magnus, meaning "Great" in Latin, was used as cognomen of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus in the first century BC. The best-known use of the name during the Roman Empire is for the fourth-century Western Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus. The name gained wid ...

'' – "the Great" – after his boyhood hero Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

. His adversaries gave him the nickname ''adulescentulus carnifex'' ("teenage butcher") for his ruthlessness.

In 60 BC, Pompey joined Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (; 115 – 53 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome." Wallechinsky, David & Wallace, I ...

and Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

in the military-political alliance known as the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many ve ...

. Pompey married Caesar's daughter, Julia

Julia is usually a feminine given name. It is a Latinate feminine form of the name Julio and Julius. (For further details on etymology, see the Wiktionary entry "Julius".) The given name ''Julia'' had been in use throughout Late Antiquity (e.g ...

, which helped secure this partnership. After the deaths of Crassus and Julia, Pompey became an ardent supporter of the political faction the ''optimates

Optimates (; Latin for "best ones", ) and populares (; Latin for "supporters of the people", ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated academic dis ...

''— a conservative faction of the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

. Pompey and Caesar then began contending for leadership of the Roman state in its entirety, eventually leading to Caesar's Civil War

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was one of the last politico-military conflicts of the Roman Republic before its reorganization into the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations between Gaius Julius Caesar an ...

. Pompey was defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus

The Battle of Pharsalus was the decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War fought on 9 August 48 BC near Pharsalus in central Greece. Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the Roman Republic under the command of Pompey ...

in 48 BC, and he sought refuge in Ptolemaic Egypt, where he was assassinated in a plot by the courtiers of Ptolemy XIII

Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος Θεός Φιλοπάτωρ, ''Ptolemaĩos''; c. 62 BC – 13 January 47 BC) was Pharaoh of Egypt from 51 to 47 BC, and one of the last members of the Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC) ...

.

Early life and political debut

Pompey was born inPicenum

Picenum was a region of ancient Italy. The name is an exonym assigned by the Romans, who conquered and incorporated it into the Roman Republic. Picenum was ''Regio V'' in the Augustan territorial organization of Roman Italy. Picenum was also ...

(a region of Ancient Italy) to a local noble family. His father, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo

Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (c. 135 – 87 BC) was a Roman general and politician, who served as consul in 89 BC. He is often referred to in English as Pompey Strabo, to distinguish him from his son, the famous Pompey the Great, or from Strabo the g ...

, was the first of his branch of the '' gens Pompeia'' to achieve senatorial status in Rome, despite his provincial origins. The Romans referred to Strabo as a ''novus homo

''Novus homo'' or ''homo novus'' ( Latin for 'new man'; ''novi homines'' or ''homines novi'') was the term in ancient Rome for a man who was the first in his family to serve in the Roman Senate or, more specifically, to be elected as consul. W ...

'' (new man). Pompeius Strabo ascended the traditional ''cursus honorum

The ''cursus honorum'' (; , or more colloquially 'ladder of offices') was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The ''c ...

'', becoming quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

in 104 BC, praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

in 92 BC and consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

in 89 BC.  Pompey's father acquired a reputation for greed, political double-dealing, and military ruthlessness. He fought the Social War against Rome's Italian allies, and was granted a

Pompey's father acquired a reputation for greed, political double-dealing, and military ruthlessness. He fought the Social War against Rome's Italian allies, and was granted a triumph

The Roman triumph (Latin triumphus) was a celebration for a victorious military commander in ancient Rome. For later imitations, in life or in art, see Trionfo. Numerous later uses of the term, up to the present, are derived directly or indirectl ...

. Strabo died during the siege of Rome by the Marians, in 87 BC—either as a casualty of an epidemic, or by having been struck by lightning. His twenty-year-old son Pompey inherited his estates and the loyalty of his legions.

Pompey served under his father's command during the final years of the Social War. When his father died, Pompey was put on trial due to accusations that his father stole public property. As his father's heir, Pompey could be held to account. He discovered that the theft was committed by one of his father's freedmen. Following his preliminary bouts with his accuser, the judge took a liking to Pompey and offered his daughter Antistia in marriage, and so Pompey was acquitted.

Another

Pompey served under his father's command during the final years of the Social War. When his father died, Pompey was put on trial due to accusations that his father stole public property. As his father's heir, Pompey could be held to account. He discovered that the theft was committed by one of his father's freedmen. Following his preliminary bouts with his accuser, the judge took a liking to Pompey and offered his daughter Antistia in marriage, and so Pompey was acquitted.

Another civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

broke out between the Marians and Sulla in 84–82 BC. The Marians had previously taken over Rome while Sulla was fighting the First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War (89–85 BC) was a war challenging the Roman Republic's expanding empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Roman rule were led by Mithridat ...

(89–85 BC) against Mithridates VI

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης; 135–63 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an e ...

in Greece. In 84 BC, Sulla returned from that war, landing in Brundisium (Brindisi

Brindisi ( , ) ; la, Brundisium; grc, Βρεντέσιον, translit=Brentésion; cms, Brunda), group=pron is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

Histo ...

) in southern Italy. Pompey raised three legions from his father's veterans and his own clients in Picenum to support Sulla's march on Rome against the Marian regime of Gnaeus Papirius Carbo

Gnaeus Papirius Carbo (c. 129 – 82 BC) was thrice consul of the Roman Republic in 85, 84, and 82 BC. He was the head of the Marianists after the death of Cinna in 84 and led the resistance to Sulla during the civil war. He was proscribed by S ...

and Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbric and Jugurthine wars, he held the office of consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his important refor ...

. Cassius Dio described Pompey's troop levy as a "small band."

Sulla defeated the Marians and was appointed as Dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in time ...

. He admired Pompey's qualities and thought that he was useful for the administration of his affairs. He and his wife, Metella, persuaded Pompey to divorce Antistia and marry Sulla's stepdaughter Aemilia. Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

commented that the marriage was "characteristic of a tyranny, and benefitted the needs of Sulla rather than the nature and habits of Pompey, Aemilia being given to him in marriage when she was with a child by another man." Antistia had recently lost both her parents. Pompey accepted, but "Aemilia had scarcely entered Pompey's house before she succumbed to the pangs of childbirth." Pompey later married Mucia Tertia, but there's no record of when this took place, the sources only mentioning Pompey's divorce with her. Plutarch wrote that Pompey dismissed with contempt a report that she had had an affair while he was fighting in the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of th ...

between 66 and 63 BC. However, on his journey back to Rome, he examined the evidence more carefully and filed for divorce. Cicero wrote that the divorce was strongly approved. Cassius Dio wrote that she was the sister of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer (before 103 BC or c. 100 BC – 59 BC), a member of the powerful Caecilius Metellus family (plebeian nobility, not patrician) who were at their zenith during Celer's lifetime. A son of Quintus Caecilius Metell ...

and that Metellus Celer was angry because he had divorced her despite having had children by her.Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'', 37.49.3 Pompey and Mucia had three children: the eldest, Gnaeus Pompey ( Pompey the Younger); Pompeia Magna

Pompeia Magna (born 80/75 BC – before 35 BC) was the daughter and second child born to Roman triumvir Pompey the Great (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus) from his third marriage, to Mucia Tertia. Her elder brother was Gnaeus Pompeius and her younger bro ...

, a daughter; and Sextus Pompey

Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius ( 67 – 35 BC), also known in English as Sextus Pompey, was a Roman military leader who, throughout his life, upheld the cause of his father, Pompey the Great, against Julius Caesar and his supporters during the las ...

, the younger son. Cassius Dio wrote that Marcus Scaurus was Sextus’ half-brother on his mother's side. He was condemned to death, but later released for the sake of his mother Mucia.

Sicily, Africa and Lepidus' rebellion

The survivors of the Marians, those who were exiled after they lost Rome and those who escaped Sulla's persecution of his opponents, were given refuge on Sicily by Roman generalMarcus Perpenna Vento

Marcus Perperna (or Perpenna) Veiento (also, incorrectly, Vento; died 72 BC) was a Roman aristocrat, statesman and general. He fought in Sulla's civil war, Lepidus' failed rebellion of 77 BC and from 76 to 72 BC in the Sertorian War. He conspired ...

. Papirius Carbo had a fleet there, and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus had forced entry into the Roman province of Africa

Africa Proconsularis was a Roman province on the northern African coast that was established in 146 BC following the defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of Algeri ...

. Sulla sent Pompey to Sicily with a large force. According to Plutarch, Perpenna fled and left Sicily to Pompey. While the Sicilian cities had been treated harshly by Perpenna, Pompey treated them with kindness. However, Pompey "treated Carbo in his misfortunes with an unnatural insolence," taking Carbo in fetters to a tribunal he presided over, examining him closely "to the distress and vexation of the audience," and finally, sentencing him to death. Pompey treated Quintus Valerius "with unnatural cruelty." His opponents dubbed him ''adulescentulus carnifex'' (adolescent butcher). While Pompey was still in Sicily, Sulla ordered him to the province of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

to fight Gnaeus Domitius, who had assembled a large force there. Pompey left his brother-in-law, Gaius Memmius, in control of Sicily and sailed his army to Africa. When he got there, 7,000 of the enemy forces went over to him. Domitius was subsequently defeated at the battle of Utica

The Battle of Utica took place early in 240 BC between a Carthaginian army commanded by Hanno and a force of rebellious mutineers possibly led by Spendius. It was the first major engagement of the Mercenary War between Carthage and the co ...

and died when Pompey attacked his camp. Some cities surrendered, some were taken by storm. King Hiarbas of Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

, who was an ally of Domitius, was captured and executed. Pompey invaded Numidia and subdued it in forty days, restoring Hiempsal II

Hiempsal II was a king of Numidia (ruled 88 BC - 60 BC). He was the son of Gauda, half-brother of Jugurtha, and was the father of Juba I.

In 88 BC, after the triumph of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, when Gaius Marius and his son fled from Rome to Af ...

to the throne. When he returned to the Roman province of Africa, Sulla ordered him to send back the rest of his troops and remain there with one legion to wait for his successor. This turned the soldiers who had to stay behind against Sulla, but Pompey said that he would rather kill himself than go against Sulla. When Pompey returned to Rome, everyone welcomed him. To outdo them, Sulla saluted him as ''Magnus'' (the Great), after Pompey's boyhood hero Alexander the Great, and ordered the others to give him this cognomen.

Pompey asked for a triumph

The Roman triumph (Latin triumphus) was a celebration for a victorious military commander in ancient Rome. For later imitations, in life or in art, see Trionfo. Numerous later uses of the term, up to the present, are derived directly or indirectl ...

, but Sulla refused because the law allowed only a consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

or a praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

to celebrate a triumph, and said that if Pompey—who was too young even to be a senator—were to do so, he would make both Sulla's regime and his honor odious. Plutarch commented that Pompey "had scarcely grown a beard as yet." Pompey replied that more people worshiped the rising sun than the setting sun, implying that his power was on the increase, while Sulla's was on the wane. According to Plutarch, Sulla did not hear him directly but saw expressions of astonishment on the faces of those that did. When Sulla asked what Pompey had said, he was taken aback by the comment and cried out twice "Let him have his triumph!" Pompey tried to enter the city on a chariot drawn by four of the many elephants he had captured in Africa, but the city gate was too narrow and he changed over to his horses. His soldiers, who had not received as much of a share of the war booty as they expected, threatened a mutiny, but Pompey said that he did not care and that he would rather give up his triumph. Pompey went ahead with his extra-legal triumph. Sulla was annoyed, but did not want to hinder his career and kept quiet. However, in 79 BC, when Pompey canvassed for Lepidus and succeeded in making him a consul against Sulla's wishes, Sulla warned Pompey to watch out because he had made an adversary stronger than him. He omitted Pompey from his will.

After Sulla's death in 78 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus tried to revive the fortunes of the ''populares''. He became the new leader of the reformist movement silenced by Sulla. He tried to prevent Sulla from receiving a state funeral and from having his body buried in the Campus Martius. Pompey opposed this and ensured Sulla's burial with honours. In 77 BC, when Lepidus had left for his

After Sulla's death in 78 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus tried to revive the fortunes of the ''populares''. He became the new leader of the reformist movement silenced by Sulla. He tried to prevent Sulla from receiving a state funeral and from having his body buried in the Campus Martius. Pompey opposed this and ensured Sulla's burial with honours. In 77 BC, when Lepidus had left for his proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ' ...

ar command (he was allocated the provinces of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in what is now Languedoc and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Province"), because it was the ...

), his political opponents moved against him and he was recalled from his proconsular command. When he refused to return, they declared him an enemy of the state, and, when Lepidus did move back to Rome, he did so at the head of an army.

The Senate passed a Consultum Ultimum (the Ultimate Decree) which called on the interrex

The interrex (plural interreges) was literally a ruler "between kings" (Latin ''inter reges'') during the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic. He was in effect a short-term regent.

History

The office of ''interrex'' was supposedly created follow ...

Appius Claudius and the proconsul Quintus Lutatius Catulus to take necessary measures to preserve public safety. Catulus and Claudius persuaded Pompey, who had several legions' worth of veterans in Picenum (in the northeast of Italy) ready to take up arms at his command, to join their cause. Pompey, invested as a legate

Legate may refer to:

* Legatus, a higher ranking general officer of the Roman army drawn from among the senatorial class

:*Legatus Augusti pro praetore, a provincial governor in the Roman Imperial period

*A member of a legation

*A representative, ...

with propraetor

In ancient Rome a promagistrate ( la, pro magistratu) was an ex-consul or ex-praetor whose ''imperium'' (the power to command an army) was extended at the end of his annual term of office or later. They were called proconsuls and propraetors. Thi ...

ial powers, quickly recruited an army from among his veterans and threatened Lepidus, who had marched his army to Rome, from the rear. Pompey penned up Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC), often referred to simply as Brutus, was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Ser ...

, one of Lepidus's lieutenants, in Mutina

Modena (, , ; egl, label= Modenese, Mòdna ; ett, Mutna; la, Mutina) is a city and '' comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy.

A town, and seat o ...

.

After a lengthy siege, Brutus surrendered. Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

wrote that it was not known whether Brutus had betrayed his army or whether his army had betrayed him. Brutus was given an escort and retired to a town by the river Po, but the next day he was apparently assassinated on Pompey's orders. Pompey was blamed for this, because he had written that Brutus had surrendered of his own accord, and then wrote a second letter denouncing him after he had him murdered.Plutarch, ''Life of Pompey'', p. 16

Catulus, who had recruited an army at Rome, now took on Lepidus, directly defeating him in a battle just to the north of Rome. After having dealt with Brutus, Pompey marched against Lepidus' rear, catching him near Cosa. Although Pompey defeated him, Lepidus was still able to embark part of his army and retreat to Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

. Lepidus fell ill while on Sardinia and died, allegedly because he found out that his wife had had an affair.

Sertorian War, Third Servile War and first consulship

Sertorian War

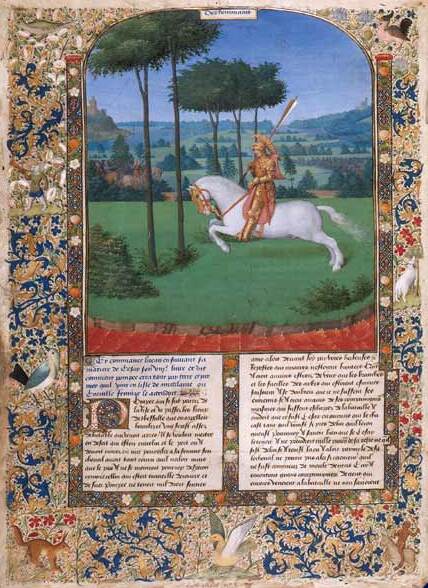

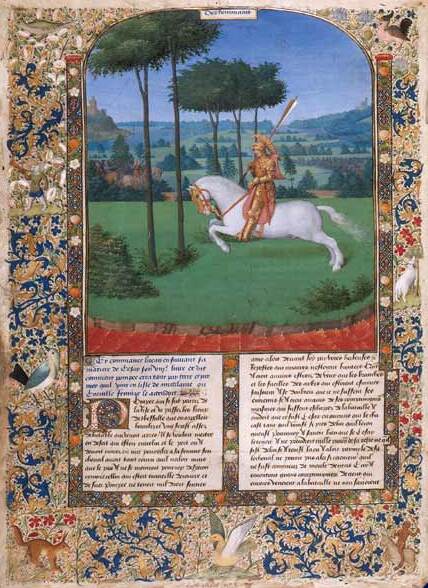

Quintus Sertorius

Quintus Sertorius (c. 126 – 73 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who led a large-scale rebellion against the Roman Senate on the Iberian peninsula. He had been a prominent member of the populist faction of Cinna and Marius. During the l ...

, the last survivor of the Cinna-Marian faction (Sulla's main opponents during the civil wars of 88-80 BC), waged an effective guerrilla war against the officials of the Sullan regime in Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

. He was able to rally the local tribes, particularly the Lusitanians

The Lusitanians ( la, Lusitani) were an Indo-European speaking people living in the west of the Iberian Peninsula prior to its conquest by the Roman Republic and the subsequent incorporation of the territory into the Roman province of Lusitania. ...

and the Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BCE. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strab ...

, in what came to be called the Sertorian War

The Sertorian War was a civil war fought from 80 to 72 BC between a faction of Roman rebels ( Sertorians) and the government in Rome (Sullans). The war was fought on the Iberian Peninsula (called ''Hispania'' by the Romans) and was one of the ...

(80-72 BC). Sertorius's guerrilla tactics wore down the Sullans in Hispania; he even drove the proconsul Metellus Pius

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius (c. 128 – 63 BC) was a Roman politician and general. Like the other members of the influential Caecilii Metelli family, he was a leader of the Optimates, the conservative faction opposed to the Populares during t ...

from his province of Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a region of Hispania during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of modern Spain and extending to all of Lusitania ( ...

. Pompey, who had just successfully assisted the consul Catulus

Gaius Lutatius Catulus ( 242–241 BC) was a Roman statesman and naval commander in the First Punic War. He was born a member of the plebeian gens Lutatius. His cognomen "Catulus" means "puppy". There are no historical records of his life ...

in putting down the rebellion of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, asked to be sent to reinforce Metellus. He had not disbanded his legions after squashing the rebels and remained under arms near the city with various excuses until he was ordered to Hispania by the senate on a motion of Lucius Philippus. A senator asked Philippus if he "thought it necessary to send Pompey out as proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ' ...

. 'No, indeed!' said Philippus, 'but as proconsuls,' implying that both the consuls of that year were good for nothing." Pompey's proconsular mandate was extra-legal, as a proconsulship was the extension of the military command (but not the public office) of a consul. Pompey, however, was not a consul and had never held public office. His career seems to have been driven by desire for military glory and disregard for traditional political constraints.

Pompey recruited an army of 30,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry, its size evidence of the seriousness of the threat posed by Sertorius. On Pompey's staff were his old lieutenant Afranius

The gens Afrania was a plebeian family at Rome, which is first mentioned in the second century BC. The first member of this gens to achieve prominence was Gaius Afranius Stellio, who became praetor in 185 BC.''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biograp ...

, D. Laelius, Petreius, C. Cornelius, probably Gabinius and Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (; 116–27 BC) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Vergil and Cicero). He is sometimes calle ...

.John Leach, ''Pompey the Great'', p. 45 Gaius Memmius, his brother-in-law, who was already serving in Spain under Metellus, was transferred to his command and served him as a quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

. On his way to Hispania, he opened a new route through the Alps and subdued tribes that had rebelled in Gallia Narbonensis

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in what is now Languedoc and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Province"), because it was th ...

. Cicero later describes Pompey leading his legions to Spain through a welter of carnage in a transalpine war during the autumn of 77 BC. After a hard and bloody campaign, Pompey wintered his army near the Roman colony of Narbo Martius

Narbonne (, also , ; oc, Narbona ; la, Narbo ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Me ...

. In the spring of 76 BC, he marched on and entered the Iberian peninsula through the Col de Petrus. He would remain in Hispania from 76 BC to 71 BC. Pompey's arrival gave the men of Metellus Pius new hope and led to some local tribes, which were not tightly associated with Sertorius, to change sides. According to Appian, as soon as Pompey arrived, he marched to lift the siege of Lauron, where he suffered a substantial defeat at the hands of Sertorius himself. It was a serious blow to Pompey's prestige. Pompey spent the rest of 76 BC recovering from the defeat and preparing for the coming campaign.Plutarch, ''Life of Sertorius'', p. 18

In 75 BC, Sertorius decided to take on Metellus while he left the battered Pompey to two of his legates (Perpenna and Herennius). In a battle near Valentia, Pompey defeated Perpenna and Herennius and regained some of his prestige.Plutarch, ''Life of Pompey'', p. 18 Sertorius, hearing of the defeat, left Metellus to his second-in-command, Hirtuleius, and took over the command against Pompey. Metellus then promptly defeated Hirtuleius at the Battle of Italica

The Battle of Italica was fought in 75 BC between a rebel army under the command of Lucius Hirtuleius a legate of the Roman rebel Quintus Sertorius and a Roman Republican army under the command of the Roman general and proconsul of Hispania Ulte ...

and marched after Sertorius. Pompey and Sertorius, both not wanting to wait for the arrival of Metellus (Pompey wanted the glory of finishing off Sertorius for himself and Sertorius did not relish fighting two armies at once), hastily engaged in the indecisive Battle of Sucro

The Battle of Sucro was fought in 75 BC between a rebel army under the command of the Roman rebel Quintus Sertorius and a Roman army under the command of the Roman general Pompey. The battle was fought on the banks of the river Sucro near a to ...

. On Metellus’ approach, Sertorius marched inland. Pompey and Metellus pursued him to a settlement called "Seguntia" (certainly not the more known Saguntum

Sagunto ( ca-valencia, Sagunt) is a municipality of Spain, located in the province of Valencia, Valencian Community. It belongs to the modern fertile ''comarca'' of Camp de Morvedre. It is located c. 30 km north of the city of Valencia, cl ...

settlement on the coast, but one of the many Celtiberian towns called Seguntia, since Sertorius had withdrawn inland), where they fought an inconclusive battle. Pompey lost nearly 6,000 men and Sertorius half of that.Appian, ''Bellum Civile'', 1.110 Memmius, Pompey's brother-in-law and the most capable of his commanders, also fell. Metellus defeated Perpenna, who lost 5,000 men. According to Appian, the next day, Sertorius attacked Metellus' camp unexpectedly, but he had to withdraw because Pompey was approaching. Sertorius withdrew to Clunia

Clunia (full name ''Colonia Clunia Sulpicia'') was an ancient Roman city. Its remains are located on Alto de Castro, at more than 1000 metres above sea level, between the villages of Peñalba de Castro and Coruña del Conde, 2 km away f ...

, a mountain stronghold in present-day Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

, and repaired its walls to lure the Romans into a siege and sent officers to collect troops from other towns. He then made a sortie, passed through the enemy lines and joined his new force. He resumed his guerrilla tactics and cut off the enemy's supplies with widespread raids, while pirate tactics at sea disrupted maritime supplies. This forced the two Roman commanders to separate. Metellus went to Gaul, and Pompey wintered among the Vaccaei

The Vaccaei or Vaccei were a pre-Roman Celtic people of Spain, who inhabited the sedimentary plains of the central Duero valley, in the Meseta Central of northern Hispania (specifically in Castile and León). Their capital was ''Intercatia'' in P ...

and suffered shortages of supplies. When Pompey spent most of his private resources on the war, he asked the senate for money, threatening to go back to Italy with his army if this was refused. The consul Lucius Licinius Lucullus, canvassing for the command of the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of th ...

, believing that it would bring glory with little difficulty and fearing that Pompey would leave the Sertorian War to take on the Mithridatic one, ensured that the money was sent to keep Pompey. Pompey got his money and was stuck in Hispania until he could convincingly beat Sertorius. The "retreat" of Metellus made it seem like victory was further away then ever and led to the joke that Sertorius would be back in Rome before Pompey.

In 73 BC, Rome sent two more legions to Metellus. He and Pompey then descended from the Pyrenees to the river Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

. Sertorius and Perpenna advanced from Lusitania again. According to Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, many of the senators and other high-ranking men who had joined Sertorius were jealous of their leader. This was encouraged by Perpenna, who aspired to the chief command. They secretly sabotaged him and meted out severe punishments on the Hispanic allies, pretending that this was ordered by Sertorius. Revolts in the towns were further stirred up by these men, which caused Sertorius to kill some allies and sell others into slavery. Appian wrote that many of Sertorius' Roman soldiers defected to Metellus. Sertorius reacted with severe punishments and started using a bodyguard of Celtiberians instead of Romans. Moreover, he reproached his Roman soldiers for treachery. This aggrieved the soldiers, because they felt that they were blamed for the desertion of other soldiers and, since this was happening while they were serving under an enemy of the regime in Rome, in a sense, they were betraying their country through him. Moreover, the Celtiberians treated them with contempt as men under suspicion. These facts made Sertorius unpopular; only his skill at command kept his troops from deserting en masse.

Metellus took advantage of his enemy's poor morale, bringing many towns allied to Sertorius under subjection. Pompey besieged Palantia until Sertorius showed up to relieve the city. Pompey set fire to the city walls and retreated to Metellus. Sertorius rebuilt the wall and then attacked his enemies who were encamped around the castle of Calagurris, which led to the loss of 3000 men. In 72 BC, there were only skirmishes. However, Metellus and Pompey advanced on several towns, some of them defecting and some being attacked. Appian wrote that Sertorius fell unto "habits of luxury," drinking and consorting with women. He was defeated continually. He became hot-tempered, suspicious and cruel in punishment. Perpenna began to fear for his safety and conspired to murder Sertorius. Plutarch, instead, thought that Perpenna was motivated by ambition. He had gone to Hispania with the remnants of the army of Lepidus in Sardinia and had wanted to fight this war independently to gain glory. He had joined Sertorius reluctantly because his troops wanted to do so when they heard that Pompey was coming to Hispania, but, in all reality, he wanted to take over the supreme command.

When Sertorius was murdered, the formerly disaffected soldiers grieved for the loss of their commander whose bravery had been their salvation and were angry with Perpenna. The native troops, especially the Lusitanians, who had given Sertorius the greatest support, were angry too. Perpenna responded with the carrot and the stick: he gave gifts, made promises and released some of the men Sertorius had imprisoned, while threatening others and killing some men to strike terror. He secured the obedience of his troops, but not their true loyalty. Metellus left the fight against Perpenna to Pompey. The two skirmished for nine days. Then, as Perpenna did not think that his men would remain loyal for long, he marched into battle, but Pompey ambushed and defeated him. Frontinus wrote about the battle in his stratagems:

Pompey won against a poor commander and a disaffected army. Perpenna hid in a thicket, fearing his troops more than the enemy, and was eventually captured. Perpenna offered to produce letters to Sertorius from leading men in Rome who had invited Sertorius to Italy for seditious purposes. Pompey, fearing that this might lead to an even greater war, had Perpenna executed and burned the letters without even reading them. Pompey remained in Hispania to quell the last disorders and settle affairs. He showed a talent for efficient organisation and fair administration in the conquered province. This extended his patronage throughout Hispania and into southern Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. His departure from Hispania was marked by the erection of a Triumphal monument at the summit off the pass over the Pyrenees. On it, he recorded that, from the Alps to the limits of Further Spain, he had brought 876 towns under Roman sway.

Third Servile War

While Pompey was in Hispania, the rebellion of the slaves led bySpartacus

Spartacus ( el, Σπάρτακος '; la, Spartacus; c. 103–71 BC) was a Thracian gladiator who, along with Crixus, Gannicus, Castus, and Oenomaus, was one of the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprisin ...

(the Third Servile War

The Third Servile War, also called the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus by Plutarch, was the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic known as the Servile Wars. This third rebellion was the only one that directly ...

, 73–71 BC) broke out. Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (; 115 – 53 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome." Wallechinsky, David & Wallace, I ...

was given eight legions and led the final phase of the war. He asked the senate to summon Lucullus and Pompey back from the Third Mithridatic War and Hispania, respectively, to provide reinforcements, "but he was sorry now that he had done so, and was eager to bring the war to an end before those generals came. He knew that the success would be ascribed to the one who came up with assistance, and not to himself." The senate decided to send Pompey, who had just returned from Hispania. On hearing this, Crassus hurried to engage in the decisive battle, and routed the rebels. On his arrival, Pompey cut to pieces 6,000 fugitives from the battle. Pompey wrote to the senate that Crassus had conquered the rebels in a pitched battle, but that he himself had extirpated the war entirely.

First consulship

Pompey was granted a second triumph for his victory in Hispania, which, again, was extra-legal. He was asked to stand for the consulship, even though he was only 35 and thus below the age of eligibility to the consulship, and had not held any public office, much less climbed the ''cursus honorum

The ''cursus honorum'' (; , or more colloquially 'ladder of offices') was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The ''c ...

'' (the progression from lower to higher offices). Livy noted that Pompey was made consul after a special senatorial decree, because he had not occupied the quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

ship, was an equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or Riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

*Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes in ...

and did not have senatorial rank.Livy, ''Periochae'', 97.6 Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

wrote that "Crassus, the richest statesman of his time, the ablest speaker, and the greatest man, who looked down on Pompey and everybody else, had not the courage to sue for the consulship until he had asked the support of Pompey." Pompey accepted gladly. In the ''Life of Pompey'', Plutarch wrote that Pompey "had long wanted an opportunity of doing him some service and kindness..."Plutarch, ''Life of Pompey'', 22.2 In the ''Life of Crassus'', he wrote that Pompey "was desirous of having Crassus, in some way or other, always in debt to him for some favor".Plutarch, ''Life of Crassus'', 12.1 Pompey promoted his candidature and said in a speech that "he should be no less grateful to them for the colleague than for the office which he desired."

Pompey and Crassus were elected consuls for the year 70 BC. Plutarch wrote that, in Rome, Pompey was looked upon with both fear and great expectation. About half of the people feared that he would not disband his army, seize absolute power by arms and hand power to the Sullans. Pompey, instead, declared that he would disband his army after his triumph and then "there remained but one accusation for envious tongues to make, namely, that he devoted himself more to the people than to the senate..." When Pompey and Crassus assumed office, they did not remain friendly. In the ''Life of Crassus'', Plutarch wrote that the two men differed on almost every measure, and by their contentiousness rendered their consulship "barren politically and without achievement, except that Crassus made a great sacrifice in honour of Hercules and gave the people a great feast and an allowance of grain for three months." Towards the end of their term of office, when the differences between the two men were increasing, a man declared that Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

told him to "declare in public that you should not suffer your consuls to lay down their office until they become friends." The people called for a reconciliation. Pompey did not react, but Crassus "clasped him by the hand" and said that it was not humiliating for him to take the first step of goodwill.

Neither Plutarch nor Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τ� ...

wrote that the acrimony between Pompey and Crassus stemmed from Pompey's claim about the defeat of Spartacus. Plutarch wrote that "Crassus, for all his self-approval, did not venture to ask for the major triumph, and it was thought ignoble and mean in him to celebrate even the minor triumph on foot, called the ovation

The ovation ( la, ovatio from ''ovare'': to rejoice) was a form of the Roman triumph. Ovations were granted when war was not declared between enemies on the level of nations or states; when an enemy was considered basely inferior (e.g., slaves, p ...

(a minor victory celebration), for a servile war." According to Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς ''Appianòs Alexandreús''; la, Appianus Alexandrinus; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who flourished during the reigns of Emperors of Rome Trajan, Ha ...

, however, there was a contention for honours between the two men—a reference to the fact that Pompey claimed that he had ended the slave rebellion led by Spartacus, whereas in fact Crassus had done so. In Appian's account, there was no disbanding of armies. The two commanders refused to disband their armies and kept them stationed near the city, as neither wanted to be the first to do so. Pompey said that he was waiting the return of Metellus for his Spanish triumph; Crassus said that Pompey ought to dismiss his army first. Initially, pleas from the people were of no avail, but eventually Crassus yielded and offered Pompey the handshake.

Plutarch's reference to Pompey's "devot nghimself more to the people than to the senate" was related to a measure regarding the plebeian tribune

Tribune of the plebs, tribune of the people or plebeian tribune ( la, tribunus plebis) was the first office of the Roman state that was open to the plebeians, and was, throughout the history of the Republic, the most important check on the power o ...

s, the representatives of the plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words " commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins ...

. As part of the constitutional reforms Sulla carried out after the civil war, he revoked the power of the tribunes to veto the '' senatus consulta'' (the written advice of the senate on bills, which was usually followed to the letter), and prohibited ex-tribunes from ever holding any other office. Ambitious young plebeians had sought election to this tribunate as a stepping stone for election to other offices and to climb up the ''cursus honorum''. Therefore, the plebeian tribunate became a dead end for one's political career. He also limited the ability of the plebeian council

The ''Concilium Plebis'' ( English: Plebeian Council., Plebeian Assembly, People's Assembly or Council of the Plebs) was the principal assembly of the common people of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative/judicial assembly ...

(the assembly of the plebeians) to enact bills by reintroducing the ''senatus auctoritas'', a pronouncement of the senate on bills that, if negative, could invalidate them. The reforms reflected Sulla's view of the plebeian tribunate as a source of subversion that roused the "rabble" (the plebeians) against the aristocracy. Naturally, these measures were unpopular among the plebeians, the majority of the population. Plutarch wrote that Pompey "had determined to restore the authority of the tribunate, which Sulla had overthrown, and to court the favour of the many" and commented that "there was nothing on which the Roman people had more frantically set their affections, or for which they had a greater yearning, than to behold that office again." Through the repeal of Sulla's measures against the plebeian tribunate, Pompey gained the favour of the people.

In the ''Life of Crassus'', Plutarch did not mention this repeal and, as mentioned above, he only wrote that Pompey and Crassus disagreed on everything and that, as a result, their consulship did not achieve anything. Yet, the restoration of tribunician powers was a highly significant measure and a turning point in the politics of the late Republic. This measure must have been opposed by the aristocracy, and it would have been unlikely that it would have been passed if the two consuls had opposed each other. Crassus does not feature much in the writings of the ancient sources. Unfortunately, the books of Livy, otherwise the most detailed of the sources which cover this period, have been lost. However, the ''Periochae'', a short summary of Livy's work, records that "Marcus Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey were made consuls... and reconstituted the tribunician powers." Suetonius wrote that, when Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

was a military tribune, "he ardently supported the leaders in the attempt to reestablish the authority of the tribunes of the commons he plebeians

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

the extent of which Sulla had curtailed." The two leaders are presumed to have been the two consuls, Crassus and Pompey.

Campaign against the pirates

Piracy in the Mediterranean became a large-scale problem, with a big network of pirates coordinating operations over wide areas with many fleets. According to Cassius Dio, the many years of war contributed to this, as a large number of fugitives joined them, since pirates were more difficult to catch or break up than bandits. The pirates pillaged coastal fields and towns. Rome was affected through shortages of imports and the supply of grains, but the Romans did not pay proper attention to the problem. They sent out fleets when "they were stirred by individual reports" and these did not achieve anything. Cassius Dio wrote that these operations caused greater distress for Rome's allies. It was thought that a war against the pirates would be big and expensive, and that it was impossible to attack or drive back all the pirates at once. As not much was done against them, some towns were turned into pirate winter quarters and raids further inland were carried out. Many pirates settled on land in various places and relied on an informal network of mutual assistance. Towns in Italy were also attacked, including Ostia, the port of Rome, with ships burned and pillaged. The pirates seized important Romans and demanded large ransoms.

Piracy in the Mediterranean became a large-scale problem, with a big network of pirates coordinating operations over wide areas with many fleets. According to Cassius Dio, the many years of war contributed to this, as a large number of fugitives joined them, since pirates were more difficult to catch or break up than bandits. The pirates pillaged coastal fields and towns. Rome was affected through shortages of imports and the supply of grains, but the Romans did not pay proper attention to the problem. They sent out fleets when "they were stirred by individual reports" and these did not achieve anything. Cassius Dio wrote that these operations caused greater distress for Rome's allies. It was thought that a war against the pirates would be big and expensive, and that it was impossible to attack or drive back all the pirates at once. As not much was done against them, some towns were turned into pirate winter quarters and raids further inland were carried out. Many pirates settled on land in various places and relied on an informal network of mutual assistance. Towns in Italy were also attacked, including Ostia, the port of Rome, with ships burned and pillaged. The pirates seized important Romans and demanded large ransoms.

Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

had been a haven for pirates for a long time. It was divided into two parts: Cilicia Trachaea (Rugged Cilicia), a mountainous area in the west, and Cilicia Pedias (Flat Cilicia) in the east, by the Limonlu river. The first Roman campaign against the pirates was led by Marcus Antonius Orator in 102 BC, in which parts of Cilicia Pedias became Roman territory, but only a small part becoming a province. Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus

Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus (c. 130 BC – 44 BC), was a Roman politician and general of the First Century BC. He was elected one of the two consuls for 79 BC. From 78 to 74 BC, as proconsul of Cilicia, he fought against the Cilician Pirat ...

was given the command of fighting piracy in Cilicia in 78–74 BC. He won several naval victories off Cilicia and occupied the coasts of nearby Lycia

Lycia ( Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is ...

and Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; grc, Παμφυλία, ''Pamphylía'') was a region in the south of Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the north b ...

. He received his agnomen of Isauricus because he defeated the Isauri, who lived in the core of the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

, which bordered on Cilicia. He incorporated Isauria into the province of Cilicia Pedias. However, much of Cilicia Pedias belonged to the kingdom of Armenia. Cilicia Trachea was still under the control of the pirates.

In 67 BC, three years after Pompey's consulship, the plebeian tribune Aulus Gabinius

Aulus Gabinius (by 101 BC – 48 or 47 BC) was a Roman statesman and general. He was an avid supporter of Pompey who likewise supported Gabinius. He was a prominent figure in the latter days of the Roman Republic.

Career

In 67 BC, when trib ...

proposed a law (''lex Gabinia

The ''lex Gabinia'' (Gabinian Law), ''lex de uno imperatore contra praedones instituendo'' (Law establishing a single commander against raiders) or ''lex de piratis persequendis'' (Law on pursuing the pirates) was an ancient Roman special law pas ...

'') for choosing "...from among the ex-consuls, a commander with full power against all the pirates." He was to have dominion over the waters of the entire Mediterranean and up to inland for three years, empowered to pick fifteen lieutenants from the senate and assign specific areas to them, allowed to have 200 ships, levy as many soldiers and oarsmen as he needed and collect as much money from the tax collectors and the public treasuries as he wished. The use of treasury in the plural might suggest power to raise funds from treasures of the allied Mediterranean states as well.Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives'', ''Life of Pompey'', 25.2 Such sweeping powers were not a problem because comparable extraordinary powers given to Marcus Antonius Creticus

Marcus Antonius Creticus (flourished 1st century BC), a member of the Antonius family, was a Roman politician during the Late Roman Republic. He is best known for his failed pirate hunting career and being the father of the general Mark Antony.

Bi ...

to fight piracy in Crete in 74 BC provided a precedent. The ''optimates

Optimates (; Latin for "best ones", ) and populares (; Latin for "supporters of the people", ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated academic dis ...

'' in the Senate remained suspicious of Pompey—this seemed yet another extraordinary appointment. Cassius Dio claimed that Gabinius "had either been prompted by Pompey or wished in any case to do him a favor... he did not directly utter Pompey's name, but it was easy to see that if, once the populace should hear of any such proposition, they would choose him." Plutarch described Gabinius as one of Pompey's intimates and claimed that he "drew up a law which gave him not an admiralty, but an out-and-out monarchy and irresponsible power over all men."

Cassius Dio wrote that Gabinius’ bill was supported by everybody except the senate, which preferred the ravages of pirates rather than giving Pompey such great powers, and that some senators attempted to kill Gabinius in the Senate House. This outraged the people, who set upon the senators. They all ran away, except for the consul Gaius Piso, who was arrested, but Gabinius had him freed. The ''optimates'' tried to persuade the other nine plebeian tribunes to oppose the bill, two of whom, Trebellius and Roscius, agreed to do so. Trebellius tried to speak against the bill at the Plebeian Assembly

The ''Concilium Plebis'' ( English: Plebeian Council., Plebeian Assembly, People's Assembly or Council of the Plebs) was the principal assembly of the common people of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative/judicial assembly ...

, but Gabinius postponed the vote and introduced a motion to remove him from the tribunate. After seventeen tribes had voted in favor of the motion, Trebellius backed down, keeping his office, but forced into silence. Having witnessed his colleague's humiliation, Roscius did not dare to speak, but suggested with a gesture that two commanders should be chosen. At this, the people "gave a great threatening shout", forcing Roscius to back down as well. The law was passed and the senate ratified it reluctantly. Pompey tried to appear as if he was forced to accept the command because of the jealousy that would be caused if he would lay claim to the post and the glory that came with it. Cassius Dio commented that Pompey was "always in the habit of pretending as far as possible not to desire the things he really wished."

Plutarch did not mention Gabinius nearly being killed. He gave details of the acrimony of the speeches against Pompey, with one of the senators proposing that Pompey should be given a colleague. Only Caesar supported the law and, in Plutarch's view, he did so "not because he cared in the least for Pompey, but because from the outset he sought to ingratiate himself with the people and win their support." In his account, the people did not attack the senators, only shouted loudly, resulting in the assembly being dissolved. On the day of the vote, Pompey withdrew to the countryside, and the ''lex Gabinia'' was passed. Pompey extracted further concessions and received 500 ships, 120,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry and twenty-four lieutenants. With the prospect of a campaign against the pirates, the prices of provisions fell. Pompey divided the sea and the coast into thirteen districts, each assigned to a commander with his own forces.

Appian gave the same number of infantry and cavalry, but the number of ships was 270, and the lieutenants were twenty-five. He listed them and their areas of command as follows: Tiberius Nero and Manlius Torquatus (in command of Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

and the Straits of Hercules); Marcus Pomponius (Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

and Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

); Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus and Publius Atilius (Africa, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

, Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

); Lucius Gellius

Lucius Gellius (c. 136 BC''Oxford Classical Dictionary'',Gellius, Lucius – c. 54 BC) was a Roman politician and general who was one of two Consuls of the Republic in 72 BC along with Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. A supporter of Pompey, ...

and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus (Italy); Plotius Varus and Terentius Varro (Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to th ...

, as far as Acarnania

Acarnania ( el, Ἀκαρνανία) is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today i ...

); Lucius Sisenna (the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

, Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean ...

, Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poi ...

, Thessaly