Polyyne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

The simple fatty acid 8,10-octadecadiynoic acid is isolated from the root bark of the legume ''Paramacrolobium caeruleum'' of the family

The simple fatty acid 8,10-octadecadiynoic acid is isolated from the root bark of the legume ''Paramacrolobium caeruleum'' of the family  Thiarubrine B is the most prevalent among several related light-sensitive

Thiarubrine B is the most prevalent among several related light-sensitive

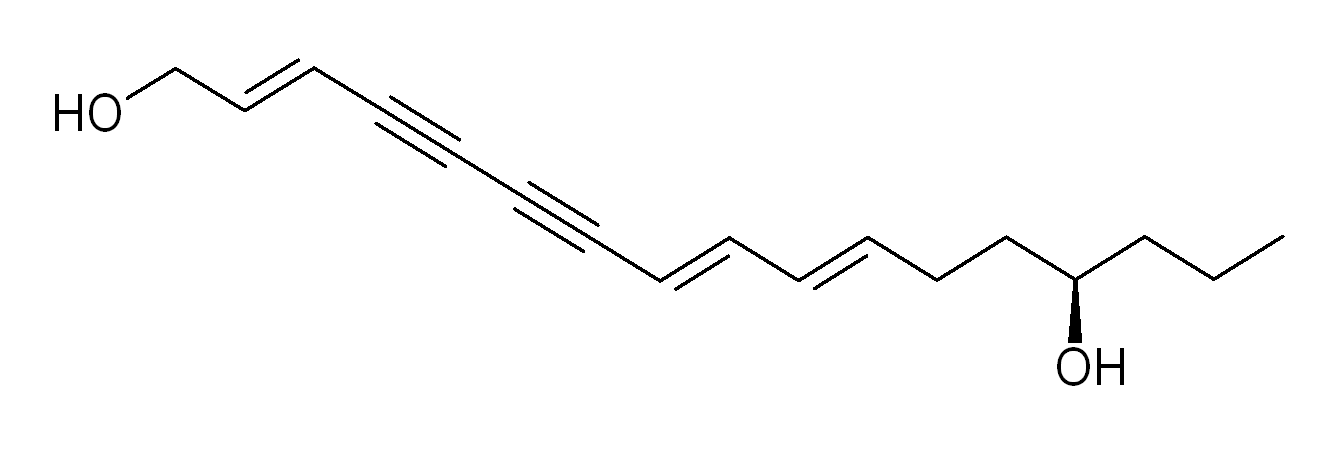

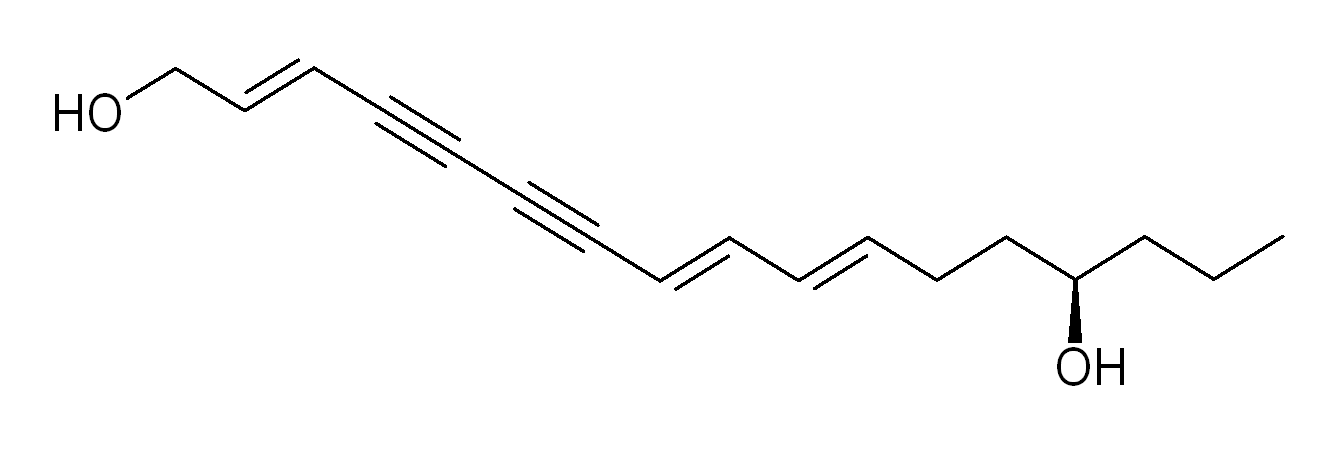

Polyynes such as falcarindiol can be found in Apiaceae vegetables like

Polyynes such as falcarindiol can be found in Apiaceae vegetables like  '' Ichthyothere'' is a genus of plants whose active constituent is a polyyne called ichthyothereol. This compound is highly

'' Ichthyothere'' is a genus of plants whose active constituent is a polyyne called ichthyothereol. This compound is highly  Dihydromatricaria acid is a polyyne produced and secreted by soldier beetles as a chemical defense.

Dihydromatricaria acid is a polyyne produced and secreted by soldier beetles as a chemical defense.

In

In organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J ...

, a polyyne () is any organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. Th ...

with alternating single and triple bond

A triple bond in chemistry is a chemical bond between two atoms involving six bonding electrons instead of the usual two in a covalent single bond. Triple bonds are stronger than the equivalent single bonds or double bonds, with a bond order o ...

s; that is, a series of consecutive alkyne

\ce

\ce

Acetylene

\ce

\ce

\ce

Propyne

\ce

\ce

\ce

\ce

1-Butyne

In organic chemistry, an alkyne is an unsaturated hydrocarbon containing at least one carbon—carbon triple bond. The simplest acyclic alkynes with only one triple bond and n ...

s, with ''n'' greater than 1. These compounds are also called polyacetylenes, especially in the natural products and chemical ecology literature, even though this nomenclature more properly refers to acetylene

Acetylene ( systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pure ...

polymers composed of alternating single and double bonds with ''n'' greater than 1. They are also sometimes referred to as oligoynes,

or carbinoids after " carbyne" , the hypothetical allotrope of carbon that would be the ultimate member of the series.

In ''Avancés récentes en chimie des acétylènes – Recent advances in acetylene chemistry''

The synthesis of this substance has been claimed several times since the 1960s, but those reports have been disputed. Indeed, the substances identified as short chains of "carbyne" in many early organic synthesis attempts would be called polyynes today.

The simplest polyyne is diacetylene

Diacetylene (also known as butadiyne) is the organic compound with the formula C4H2. It is the simplest compound containing two triple bonds. It is first in the series of polyynes, which are of theoretical but not of practical interest.

Occurr ...

or butadiyne, . Along with cumulenes, polyynes are distinguished from other organic chains by their rigidity and high conductivity, both of which make them promising as wires in molecular nanotechnology. Polyynes have been detected in interstellar molecular clouds where hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

is scarce.

Synthesis

The first reported synthesis of a polyyne was performed in 1869 by , who observed that copper phenylacetylide () undergoesoxidative

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

dimerization

A dimer () ('' di-'', "two" + ''-mer'', "parts") is an oligomer consisting of two monomers joined by bonds that can be either strong or weak, covalent or intermolecular. Dimers also have significant implications in polymer chemistry, inorganic che ...

in the presence of air to produce diphenylbutadiyne ().

Interest in these compounds has stimulated research into their preparation by organic synthesis

Organic synthesis is a special branch of chemical synthesis and is concerned with the intentional construction of organic compounds. Organic molecules are often more complex than inorganic compounds, and their synthesis has developed into one o ...

by several general routes. As a main synthetic tool usually acetylene homocoupling reactions like the Glaser coupling or its associated Elinton and Hay protocols are used. Moreover, many of such procedures involve a Cadiot–Chodkiewicz coupling

The Cadiot–Chodkiewicz coupling in organic chemistry is a coupling reaction between a terminal alkyne and a haloalkyne catalyzed by a copper(I) salt such as copper(I) bromide and an amine base.Cadiot,

P.; Chodkiewicz, W. In Chemistry of Acetyl ...

or similar reactions to unite two separate alkyne building-blocks or by alkylation of a pre-formed polyyne unit. In addition to that, Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell rearrangement

The Fritsch–Buttenberg–Wiechell rearrangement, named for Paul Ernst Moritz Fritsch (1859–1913), Wilhelm Paul Buttenberg, and Heinrich G. Wiechell, is a chemical reaction whereby a 1,1-diaryl-2-bromo-alkene rearranges to a 1,2-diaryl-alkyne b ...

was used as crucial step during the synthesis of the longest known polyyne ().

An elimination of chlorovinylsilanes was used as a final step in the synthesis of the longest known phenyl end-capped polyynes.

Organic and organosilicon polyynes

Using various techniques, polyynes with ''n'' up to 4 or 5 were synthesized during the 1950s. Around 1971, T. R. Johnson and D. R. M. Walton developed the use of end-caps of the form –, where R was usually anethyl group

In organic chemistry, an ethyl group (abbr. Et) is an alkyl substituent with the formula , derived from ethane (). ''Ethyl'' is used in the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry's nomenclature of organic chemistry for a saturated ...

, to protect the polyyne chain during the chain-doubling reaction using Hay's catalyst (a copper(I)– TMEDA complex). With that technique they were able to obtain polyynes like with ''n'' up to 8 in pure state, and with ''n'' up to 16 in solution.

Later Tykwinski and co-workers were be able to obtain polyynes with chain length up to C20.

A polyyne compound with 10 acetylenic units (20 atoms), with the ends capped by Fréchet-type aromatic

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic ( ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to satur ...

polyether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be ...

dendrimers, was isolated and characterized in 2002. Moreover, the synthesis of dicyanopolyynes with up to 8 acetylenic units was reported. The longest phenyl end-capped polyynes were reported by Cox and co-workers in 2007. As of 2010, the polyyne with the longest chain yet isolated had 22 acetylenic units (44 carbon atoms), end-capped with tris(3,5-di-t-butylphenyl)methyl

Tris, or tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, or known during medical use as tromethamine or THAM, is an organic compound with the formula (HOCH2)3CNH2, one of the twenty Good's buffers. It is extensively used in biochemistry and molecular biology as ...

groups.

Alkyne

\ce

\ce

Acetylene

\ce

\ce

\ce

Propyne

\ce

\ce

\ce

\ce

1-Butyne

In organic chemistry, an alkyne is an unsaturated hydrocarbon containing at least one carbon—carbon triple bond. The simplest acyclic alkynes with only one triple bond and n ...

s with the formula and ''n'' from 2 to 6 can be detected in the decomposition products of partially oxidized copper(I) acetylide ( (an acetylene derivative known since 1856 or earlier) by hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the dige ...

. A "carbonaceous" residue left by the decomposition also has the spectral signature of chains.

Organometallics

Organometallic polyynes capped with metal complexes are well characterized. As of the mid-2010s, the most intense research has concerned rhenium (, ''n'' = 3–10), ruthenium (, ''n'' = 4–10),iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

(), platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

(, ''n'' = 8–14), palladium

Palladium is a chemical element with the symbol Pd and atomic number 46. It is a rare and lustrous silvery-white metal discovered in 1803 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston. He named it after the asteroid Pallas, which was itself ...

(, ''n'' = 3–5, Ar = aryl

In organic chemistry, an aryl is any functional group or substituent derived from an aromatic ring, usually an aromatic hydrocarbon, such as phenyl and naphthyl. "Aryl" is used for the sake of abbreviation or generalization, and "Ar" is used ...

), and cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, p ...

(, ''n'' = 7–13) complexes.

Stability

Long polyyne chains are said to be inherently unstable in bulk because they can cross-link with each other exothermically. Explosions are a real hazard in this area of research. They can be fairly stable, even against moisture andoxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

, if the end hydrogen atoms are replaced with a suitably inert end-group, such as ''tert''-butyl or trifluoromethyl. Bulky end-groups, that can keep the chains apart, work especially well at stabilizing polyynes. In 1995 the preparation of carbyne chains with over 300 carbon atoms was reported using this technique. However the report has been contested by a claim that the detected molecules were fullerene-like structures rather than long polyynes.

Polyyne chains have also been stabilised to heating by co-deposition with silver nanoparticles, and by complexation with a mercury-containing tridentate Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

to form layered adducts

An adduct (from the Latin ''adductus'', "drawn toward" alternatively, a contraction of "addition product") is a product of a direct addition of two or more distinct molecules, resulting in a single reaction product containing all atoms of all co ...

. Long polyyne chains encapsulated in double-walled carbon nanotubes

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon na ...

or in the form of rotaxanes have also been shown to be stable. Despite rather low stability of longer polyynes there are some examples of their use as synthetic precursors in organic and organometallic synthesis.

Structure

Synthetic polyynes of the form , with ''n'' about 8 or more, often have a smoothly curved or helical backbone in the crystalline solid state, presumably due to crystal packing effects. For example, when the cap R is triisopropylsilyl and ''n'' is 8,X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

of the substance (a crystalline orange/yellow solid) shows the backbone bent by about 25–30 degrees in a broad arch, so that each C−C≡C angle deviates by 3.1 degrees from a straight line. This geometry affords a denser packing, with the bulky cap of an adjacent molecule nested into the concave side of the backbone. As a result, the distance between backbones of neighboring molecules is reduced to about 0.35 to 0.5 nm, near the range at which one expects spontaneous cross-linking. The compound is stable indefinitely at low temperature, but decomposes before melting. In contrast, the homologous molecules with ''n'' = 4 or ''n'' = 5 have nearly straight backbones that stay at least 0.5 to 0.7 nm apart, and melt without decomposing.

Natural occurrence

Biological origins

A wide range of organisms synthesize polyynes. These chemicals have various biological activities, including as flavorings and pigments, chemical repellents and toxins, and potential application to biomedical research and pharmaceuticals. In plants, polyynes are found mainly inAsterids

In the APG IV system (2016) for the classification of flowering plants, the name asterids denotes a clade (a monophyletic group). Asterids is the largest group of flowering plants, with more than 80,000 species, about a third of the total fl ...

clade, especially in the sunflower

The common sunflower (''Helianthus annuus'') is a large annual forb of the genus ''Helianthus'' grown as a crop for its edible oily seeds. Apart from cooking oil production, it is also used as livestock forage (as a meal or a silage plant), ...

, carrot

The carrot ('' Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', na ...

, ginseng and bellflower families. However, they can also be found in some members of the tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

, olax

''Olax'' is a plant genus in the family Olacaceae.

The name derives from the Latin, ''olax'' (malodorous), and refers to the unpleasant scent of some of the ''Olax'' species. ''Olax'' is an Old World genus represented by several climbers, som ...

, and sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus '' Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods for ...

families. The earliest polyyne to be isolated was dehydromatricaria ester (DME) in 1826; however, it was not fully characterized until later.

The simple fatty acid 8,10-octadecadiynoic acid is isolated from the root bark of the legume ''Paramacrolobium caeruleum'' of the family

The simple fatty acid 8,10-octadecadiynoic acid is isolated from the root bark of the legume ''Paramacrolobium caeruleum'' of the family Caesalpiniaceae

Caesalpinioideae is a botanical name at the rank of subfamily, placed in the large family Fabaceae or Leguminosae. Its name is formed from the generic name ''Caesalpinia''. It is known also as the peacock flower subfamily. The Caesalpinioideae ar ...

and has been investigated as a photopolymerizable unit in synthetic phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s.

pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compou ...

s that have been isolated from the Giant Ragweed

''Ambrosia trifida'', the giant ragweed, is a species of flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. It is native to North America, where it is widespread in Canada, the United States, and northern Mexico.

Distribution

It is present in Europ ...

(''Ambrosia trifida''), a plant used in herbal medicine. The thiarubrines have antibiotic, antiviral, and nematocidal activity, and activity against HIV-1 that is mediated by exposure to light.

carrot

The carrot ('' Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', na ...

, celery

Celery (''Apium graveolens'') is a marshland plant in the family Apiaceae that has been cultivated as a vegetable since antiquity. Celery has a long fibrous stalk tapering into leaves. Depending on location and cultivar, either its stalks, ...

, fennel

Fennel (''Foeniculum vulgare'') is a flowering plant species in the carrot family. It is a hardy, perennial herb with yellow flowers and feathery leaves. It is indigenous to the shores of the Mediterranean but has become widely naturalized ...

, parsley

Parsley, or garden parsley (''Petroselinum crispum'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae that is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean region (Sardinia, Lebanon, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, southern Italy, Greece, ...

and parsnip where they show cytotoxic activities. Aliphatic -polyynes of the falcarinol type were described to act as metabolic modulators and are studied as potential health-promoting nutraceutical

A nutraceutical or bioceutical is a pharmaceutical alternative which claims physiological benefits. In the US, "nutraceuticals" are largely unregulated, as they exist in the same category as dietary supplements and food additives by the FDA, un ...

s. Falcarindiol is the main compound responsible for bitterness in carrots

The carrot (''Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', nati ...

, and is the most active among several polyynes with potential anticancer activity found in Devil's club (''Oplopanax horridus''). Other polyynes from plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s include oenanthotoxin

Oenanthotoxin is a toxin extracted from hemlock water-dropwort ('' Oenanthe crocata'') and other plants of the genus '' Oenanthe''. It is a central nervous system poison, and acts as a noncompetitive antagonist of the neurotransmitter gamma-amino ...

and cicutoxin

Cicutoxin is a naturally-occurring poisonous chemical compound produced by several plants from the family Apiaceae including water hemlock (''Cicuta'' species) and water dropwort (''Oenanthe crocata''). The compound contains polyene, polyyne, ...

, which are poisons found in water dropwort (''Oenanthe spp.'') and water hemlock

''Cicuta'', commonly known as water hemlock, is a genus of four species of highly poisonous plants in the family Apiaceae. They are perennial herbaceous plants which grow up to tall, having distinctive small green or white flowers arranged in a ...

(''Cicuta spp.'').

'' Ichthyothere'' is a genus of plants whose active constituent is a polyyne called ichthyothereol. This compound is highly

'' Ichthyothere'' is a genus of plants whose active constituent is a polyyne called ichthyothereol. This compound is highly toxic

Toxicity is the degree to which a chemical substance or a particular mixture of substances can damage an organism. Toxicity can refer to the effect on a whole organism, such as an animal, bacterium, or plant, as well as the effect on a sub ...

to fish

Fish are Aquatic animal, aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack Limb (anatomy), limbs with Digit (anatomy), digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and Chondrichthyes, cartilaginous and bony fish as we ...

and mammals. ''Ichthyothere terminalis'' leaves

A leaf ( : leaves) is any of the principal appendages of a vascular plant stem, usually borne laterally aboveground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, st ...

have traditionally been used to make poisoned bait by indigenous peoples of the lower Amazon basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

.

Dihydromatricaria acid is a polyyne produced and secreted by soldier beetles as a chemical defense.

Dihydromatricaria acid is a polyyne produced and secreted by soldier beetles as a chemical defense.

In space

The octatetraynyl radicals and hexatriynyl radicals together with their ions are detected in space where hydrogen is rare. Moreover, there have been claims that polyynes have been found in astronomical impact sites on Earth as part of the mineralChaoite

Chaoite, or white carbon, is a mineral described as an allotrope of carbon whose existence is disputed. It was discovered in shock-fused graphite gneiss from the Ries crater in Bavaria. It has been described as slightly harder than graphite, with ...

, but this interpretation has been contested. See Astrochemistry.

See also

* Cyanopolyyne * Enediyne * EnyneReferences

{{Molecules detected in outer space Astrochemistry Conjugated hydrocarbons