Polygonal system on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A polygonal fort is a type of

A polygonal fort is a type of

The bastion system of fortification had dominated military thinking since its introduction in 16th century Italy, until the first decades of the 19th century. The French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, also devised an effective method to defeat them. Before Vauban, besiegers had driven a

The bastion system of fortification had dominated military thinking since its introduction in 16th century Italy, until the first decades of the 19th century. The French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, also devised an effective method to defeat them. Before Vauban, besiegers had driven a

Despite the conservatism of the French engineer corps, two French engineers experimented on a modest scale with Montalembert's ideas for detached forts.

Despite the conservatism of the French engineer corps, two French engineers experimented on a modest scale with Montalembert's ideas for detached forts.  Montalembert's work was also allowed to take concrete form during his lifetime in the field of coastal fortification. In 1778, he was commissioned to build a fort on the

Montalembert's work was also allowed to take concrete form during his lifetime in the field of coastal fortification. In 1778, he was commissioned to build a fort on the

After the final fall of Napoleon I in 1815, the

After the final fall of Napoleon I in 1815, the  The detached forts were polygons of four or five sides in plan, with the front faces of the rampart angled at 95°. The rear or gorge of the fort was closed with a masonry wall, sufficient to repel a surprise infantry attack but easily demolished by the defenders' artillery should the fort be captured by the attackers. In the centre of the gorge wall was a

The detached forts were polygons of four or five sides in plan, with the front faces of the rampart angled at 95°. The rear or gorge of the fort was closed with a masonry wall, sufficient to repel a surprise infantry attack but easily demolished by the defenders' artillery should the fort be captured by the attackers. In the centre of the gorge wall was a

The first

The first  In the United States, it had been decided at an early stage that it would be impractical to provide landward fortifications for rapidly expanding cities but a considerable investment had been made in seaward defences in the form of multi-tiered casemated batteries, originally based on Montalembert's designs. During the

In the United States, it had been decided at an early stage that it would be impractical to provide landward fortifications for rapidly expanding cities but a considerable investment had been made in seaward defences in the form of multi-tiered casemated batteries, originally based on Montalembert's designs. During the

From the mid-19th century, chemists produced the first

From the mid-19th century, chemists produced the first

On the Eastern Front, most polygonal fortifications were also quickly overcome by heavy artillery. The

On the Eastern Front, most polygonal fortifications were also quickly overcome by heavy artillery. The  Following these failures, the French high command concluded that fixed fortifications were obsolete and they began the process of disarming their forts, since there was a grave shortage of medium artillery pieces in their field armies. In February 1916, the Germans began the Battle of Verdun, hoping to force the French to squander their forces in costly counter-attacks in an effort to regain it. They found that the Verdun forts, which had been recently upgraded with extra layers of concrete and sand, were resistant to their heaviest shells. Fort Douaumont was captured, almost by accident, by a small party of Germans who climbed through an unattended embrasure, the rest of the forts could not permanently be subdued and the offensive was eventually called off in July after huge casualties on both sides.

Following these failures, the French high command concluded that fixed fortifications were obsolete and they began the process of disarming their forts, since there was a grave shortage of medium artillery pieces in their field armies. In February 1916, the Germans began the Battle of Verdun, hoping to force the French to squander their forces in costly counter-attacks in an effort to regain it. They found that the Verdun forts, which had been recently upgraded with extra layers of concrete and sand, were resistant to their heaviest shells. Fort Douaumont was captured, almost by accident, by a small party of Germans who climbed through an unattended embrasure, the rest of the forts could not permanently be subdued and the offensive was eventually called off in July after huge casualties on both sides.

The war opened with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; by 13 September, Warsaw and the partly-modernised fortress of Modlin had been surrounded. The fortress was separated from Warsaw on 22 September and despite numerous German infantry assaults supported by heavy artillery and dive bombing, Modlin was not surrendered until 29 September after receiving the news that Warsaw had fallen.

On 10 May 1940, German forces attacked the new Belgian forts, quickly Battle of Fort Eben-Emael, neutralising Eben-Emael by airborne assault. The three other forts were bombarded by Skoda 305 mm Model 1911, 305 mm howitzers and dive-bombers and each repulsed several infantry assaults. Two of the forts surrendered on 21 May and the last, Fort de Battice, on the following day, having been by-passed by the main German thrust. Modernised French polygonal forts at Maubeuge were attacked on 19 May and were surrendered after their gun turrets and observation domes had been knocked out with anti-tank guns and demolition charges. Late in the war, the ring fortifications of Metz were hastily prepared for defence by German forces and was attacked by the United States Army Central, Third Army in mid-September 1944 in the Battle of Metz; the last fort surrendered nearly three months later.Zaloga, p. 70

The war opened with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; by 13 September, Warsaw and the partly-modernised fortress of Modlin had been surrounded. The fortress was separated from Warsaw on 22 September and despite numerous German infantry assaults supported by heavy artillery and dive bombing, Modlin was not surrendered until 29 September after receiving the news that Warsaw had fallen.

On 10 May 1940, German forces attacked the new Belgian forts, quickly Battle of Fort Eben-Emael, neutralising Eben-Emael by airborne assault. The three other forts were bombarded by Skoda 305 mm Model 1911, 305 mm howitzers and dive-bombers and each repulsed several infantry assaults. Two of the forts surrendered on 21 May and the last, Fort de Battice, on the following day, having been by-passed by the main German thrust. Modernised French polygonal forts at Maubeuge were attacked on 19 May and were surrendered after their gun turrets and observation domes had been knocked out with anti-tank guns and demolition charges. Late in the war, the ring fortifications of Metz were hastily prepared for defence by German forces and was attacked by the United States Army Central, Third Army in mid-September 1944 in the Battle of Metz; the last fort surrendered nearly three months later.Zaloga, p. 70

A polygonal fort is a type of

A polygonal fort is a type of fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

originating in France in the late 18th century and fully developed in Germany in the first half of the 19th century. Unlike earlier forts, polygonal forts had no bastions, which had proved to be vulnerable. As part of ring fortresses, polygonal forts were generally arranged in a ring around the place they were intended to protect, so that each fort could support its neighbours. The concept of the polygonal fort proved to be adaptable to improvements in the artillery which might be used against them, and they continued to be built and rebuilt well into the 20th century.

Bastion system deficiencies

The bastion system of fortification had dominated military thinking since its introduction in 16th century Italy, until the first decades of the 19th century. The French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, also devised an effective method to defeat them. Before Vauban, besiegers had driven a

The bastion system of fortification had dominated military thinking since its introduction in 16th century Italy, until the first decades of the 19th century. The French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, also devised an effective method to defeat them. Before Vauban, besiegers had driven a sap

Sap is a fluid transported in xylem cells (vessel elements or tracheids) or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Sap is distinct from latex, resin, or cell sap; it is a separ ...

towards the fort, until they reached the glacis, where artillery could be positioned, directly to fire on the scarp wall, to make a breach. Vauban used saps to create three successive lines of entrenchments surrounding the fort, known as "parallels". The first two parallels reduced the vulnerability of the sapping work to a sally

Sally may refer to:

People

*Sally (name), a list of notable people with the name

Military

* Sally (military), an attack by the defenders of a town or fortress under siege against a besieging force; see sally port

*Sally, the Allied reporting na ...

by the defenders, while the third parallel allowed the besiegers to launch their attack from any point along its circumference. The final refinement devised by Vauban was first used at the Siege of Ath in 1697, when he placed his artillery in the third parallel, at a point close to the bastions, from where they could ricochet their shot along the inside of the parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). ...

, dismounting the enemy guns and killing the defenders.

Other European engineers quickly adopted the three-parallel Vauban system, which became the standard method and would prove to be almost infallible. Vauban designed three systems of fortification, each having a more elaborate system of outworks, which were intended to prevent the besiegers from enfilading the bastions. During the next century, other engineers tried and failed to perfect the bastion system to nullify the Vauban type of attack. During the 18th century, it was found that the continuous enceinte

Enceinte (from Latin incinctus: girdled, surrounded) is a French term that refers to the "main defensive enclosure of a fortification". For a castle, this is the main defensive line of wall towers and curtain walls enclosing the position. Fo ...

, or main defensive enclosure of a bastion fortress, could not be made large enough to accommodate the enormous field armies which were increasingly being employed in Europe, neither could the defences be constructed far enough away from the fortress town to protect the inhabitants from bombardment by the besiegers, the range of whose guns was steadily increasing as better manufactured weapons were introduced.

Theories of Montalembert and Carnot

Marc René, marquis de Montalembert

Marc René, marquis de Montalembert (16 July 1714 – 29 March 1800) was a French military engineer and writer, known for his work on fortifications.

Life

He was born at Angoulême, and entered the French Army in 1732. He fought in the War of ...

(1714–1800) envisaged a system to prevent an opponent from establishing their parallel entrenchments by an overwhelming artillery barrage from a large number of guns, which were to be protected from return fire. The elements of his system were the replacement of bastions with tenaille

A tenaille (archaic tenalia) is an advanced defensive-work, in front of the main defences of a fortress, which takes its name from resemblance, real or imaginary, to the lip of a pair of pincers. It is "from French, literally: tongs, from Late ...

s, resulting in a defensive line with a zigzag plan, allowing for the maximum number of guns to be brought to bear and the provision of gun towers or redoubt

A redoubt (historically redout) is a fort or fort system usually consisting of an enclosed defensive emplacement outside a larger fort, usually relying on earthworks, although some are constructed of stone or brick. It is meant to protect soldi ...

s (small forts), forward of the main line, each mounting a powerful artillery battery. All the guns were to be mounted in multi-storey masonry casemates, vaulted chambers built into the ramparts of the forts. Defence of the ditches was to be by caponier

A caponier is a type of defensive structure in a fortification. Fire from this point could cover the ditch beyond the curtain wall to deter any attempt to storm the wall. The word originates from the French ', meaning "chicken coop" (a ''capon'' ...

s, covered galleries projecting into the ditch with numerous loopholes for small arms, compensating for the loss of the bastions with their flanking fire. Montalembert argued that the three elements, would provide long-range offensive fire from the casemated main curtain, defence in depth

Defence in depth (also known as deep defence or elastic defence) is a military strategy that seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating ...

from the detached forts or towers and close-in defence from the caponiers. Montalembert described his theories in an eleven-volume work called ''La Fortification Perpendiculaire'' which was published in Paris between 1776 and 1778. He summarised the benefits of his system thus; "...all is exposed to the fire of the besieged, which is everywhere superior to that of the besieger, and the latter cannot advance a step without being hit from all sides".

A full realisation of Montalembert's ambitious plans for a great inland fortress was never attempted. Almost immediately after publication, unofficial translations into German were being made of Montalembert's work and were being circulated amongst the officers of the Prussian Army. In 1780, Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst (12 November 1755 – 28 June 1813) was a Hanoverian-born general in Prussian service from 1801. As the first Chief of the Prussian General Staff, he was noted for his military theories, his reforms of the Pr ...

, a Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

ian officer who went on to reform the Prussian Army, wrote that "All foreign experts in military and engineering affairs hail Montalembert's work as the most intelligent and distinguished achievement in fortification over the last hundred years. Things are very different in France". The conservative French military establishment was wedded to the principles laid down by Vauban and improvements made by his later followers, Louis de Cormontaigne

Louis de Cormontaigne (, 1696-1752) was a French military engineer, who was the dominant technical influence on French fortifications in the 18th century. His own designs and writings constantly referenced the work of Vauban (1633-1707) and hi ...

and Charles Louis de Fourcroy

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was "f ...

. What little political influence the aristocratic Montalembert had during the ''Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for ...

'' was lost following the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

in 1792.

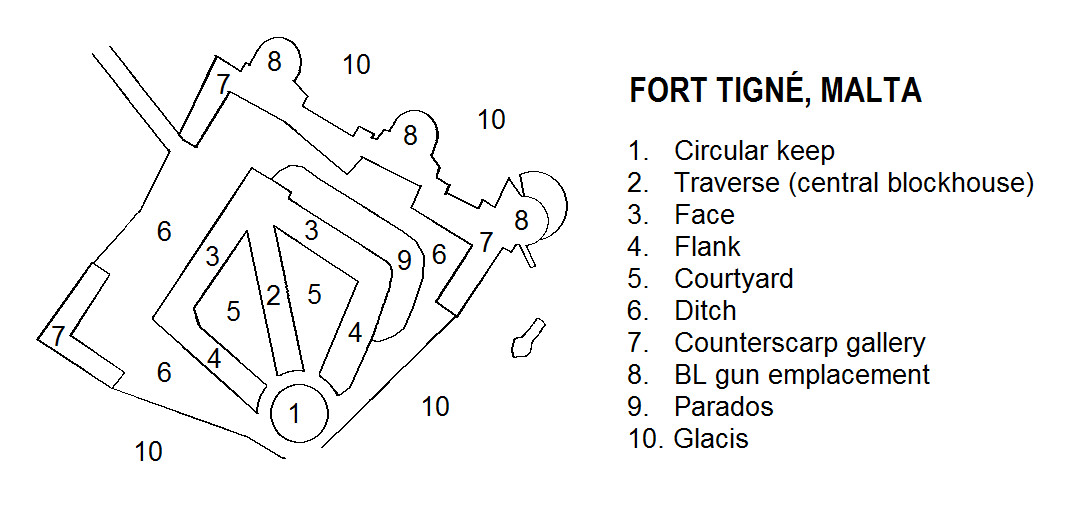

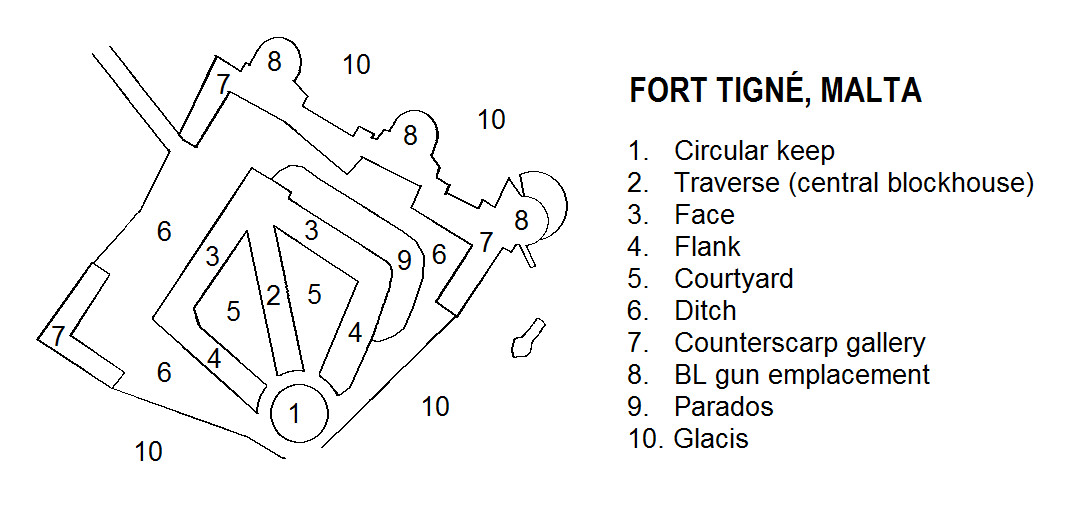

Despite the conservatism of the French engineer corps, two French engineers experimented on a modest scale with Montalembert's ideas for detached forts.

Despite the conservatism of the French engineer corps, two French engineers experimented on a modest scale with Montalembert's ideas for detached forts. Jean Le Michaud d'Arçon

Jean Claude Eléonore Le Michaud d’Arçon (18 November 1733 – 1 July 1800) was a French general, specializing in fortification. His designs include the forts at Pontarlier and Fort-Dauphin in Queyras.

Life Early life

He was the son of a law ...

, ironically one of Montalembert's detractors, designed and built a number of lunettes (an outwork resembling a detached bastion) which were in accord with Montalembert's concepts. These lunettes were constructed at Mont-Dauphin

Mont-Dauphin (; oc, Montdaufin) is a commune in the Hautes-Alpes department in southeastern France.

At the confluence of Durance and Guil rivers, overlooking the impressive canyon of the latter flowing down from Queyras valleys, Mont-Dauphin i ...

, Besançon

Besançon (, , , ; archaic german: Bisanz; la, Vesontio) is the prefecture of the department of Doubs in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. The city is located in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzer ...

, Perpignan and other border fortresses, commencing in 1791 shortly before the Revolution. In the same year, Antoine Étienne de Tousard

Antoine Étienne de Tousard (9 December 1752 – 15 September 1813) was a French people, French general and military engineer during the French Revolutionary Wars, French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He was also the last military enginee ...

took up a position on Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

as an engineer to the Order of Saint John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

and was instructed to design a small fort to command the entrance to Marsamxett Harbour

Marsamxett Harbour (), historically also referred to as Marsamuscetto, is a natural harbour on the island of Malta. It is located to the north of the larger Grand Harbour. The harbour is generally more dedicated to leisure use than the Grand H ...

called Fort Tigné

Fort Tigné ( mt, Il-Forti Tigné - Il-Fortizza ta' Tigné) is a polygonal fort in Tigné Point, Sliema, Malta. It was built by the Order of Saint John between 1793 and 1795 to protect the entrance to Marsamxett Harbour, and it is one of the o ...

. Exactly how Tousard became acquainted with d'Arcon's lunette design is unknown, but the resemblance is too close to be coincidental. It was, like d'Arcon's works, quadrilateral

In geometry a quadrilateral is a four-sided polygon, having four edges (sides) and four corners (vertices). The word is derived from the Latin words ''quadri'', a variant of four, and ''latus'', meaning "side". It is also called a tetragon, ...

in plan, divided by a traverse with a circular tower keep in the rear and the surrounding ditch was protected by counterscarp galleries. Fort Tigné, however, was a fully defensible and self-contained fort, larger and more sophisticated than d'Arcon's outworks, and is regarded as being the first true polygonal fort.

Montalembert's work was also allowed to take concrete form during his lifetime in the field of coastal fortification. In 1778, he was commissioned to build a fort on the

Montalembert's work was also allowed to take concrete form during his lifetime in the field of coastal fortification. In 1778, he was commissioned to build a fort on the Île-d'Aix

Île-d'Aix () is a commune and an island in the Charente-Maritime department, region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine (before 2015: Poitou-Charentes), off the west coast of France. It occupies the territory of the small Isle of Aix (''île d'Aix''), in the ...

, defending the port of Rochefort, Charente-Maritime

Rochefort ( oc, Ròchafòrt), unofficially Rochefort-sur-Mer (; oc, Ròchafòrt de Mar, link=no) for disambiguation, is a city and commune in Southwestern France, a port on the Charente estuary. It is a subprefecture of the Charente-Maritime de ...

. The outbreak of the Anglo-French War

The Anglo-French Wars were a series of conflicts between England (and after 1707, Britain) and France, including:

Middle Ages High Middle Ages

* Anglo-French War (1109–1113) – first conflict between the Capetian Dynasty and the House of Norma ...

forced him hastily to build his casemated fort from wood but he was able to prove that his well-designed casemates were capable of operating without choking the gunners with smoke, one of the principal objections of his detractors. The defences of the new naval base at Cherbourg were later constructed according to his system. After seeing Montalembert's coastal forts, American engineer Jonathan Williams acquired a translation of his book and took it to the United States, where it inspired the Second and Third Systems of coastal fortification; the first fully developed example being Castle Williams in New York Harbor which was started in 1807.

Lazare Carnot was an able French engineer officer, whose support for Montalembert had impeded his military career immediately after the Revolution. Taking up politics, he was made Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

in 1800 and retired from public life two years later. In 1809, Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

asked him to write a handbook for the commanders of fortresses, which was published in the following year under the title ''De la défense des places fortes''. While broadly supporting Montalembert and rejecting the bastion system, Carnot proposed that an attacker's preparations should be disrupted by massed infantry sorties, supported by a hail of high-angle fire from mortars and howitzers. Some of Carnot's innovations, such as the Carnot wall

A Carnot wall is a type of loop-holed wall built in the ditch of a fort or redoubt. It takes its name from the French mathematician, politician, and military engineer, Lazare Carnot. Such walls were introduced into the design of fortifications from ...

, a loopholed wall at the foot of the scarp face of the rampart, to shelter defending infantry, were used in many later fortifications but remained controversial.

Prussian System

After the final fall of Napoleon I in 1815, the

After the final fall of Napoleon I in 1815, the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

founded the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

, an alliance of the numerous German states, dominated by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

and the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

. Their priority was to establish a defensive system with the Fortresses of the German Confederation Under the terms of the 1815 Peace of Paris, France was obliged to pay for the construction of a line of fortresses to protect the German Confederation against any future aggression by France. All fortresses were located outside Austria and Prussia ...

against France in the west and Russia in the east. The Prussians started in the west by refortifying the fortress cities of Koblenz and Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

(german: Köln), both important crossing points on the River Rhine, under the direction of Ernst Ludwig von Aster

Ernst Ludwig von Aster (October 5, 1778 - February 10, 1855) was a German officer and a highly decorated Prussian, Saxon and Russian general of the German Campaign of 1813 and the War of the Seventh Coalition.

Aster took part in fortifying seve ...

and assisted by Gustav von Rauch

Johann Justus Georg Gustav von Rauch (1 April 1774, in Braunschweig – 2 April 1841, in Berlin) was a Prussian general of the infantry and Minister of War from 1837 to 1841.

Life

Gustav von Rauch was born as the eldest son of the later ...

, both supporters of the Montalembert system. Clearly influenced by Montalembert and Carnot, the novel feature of these new works was that they were encircled by forts, each several hundred metres out from the original enciente, carefully sited so as to make best use of the terrain and to be capable of mutual support with the neighbouring forts. The new fortifications established the principle of the ring fortress or girdle fortress.

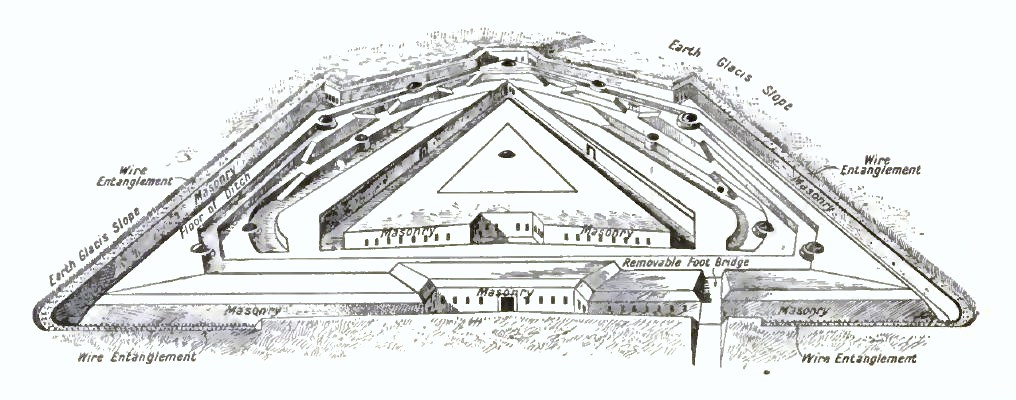

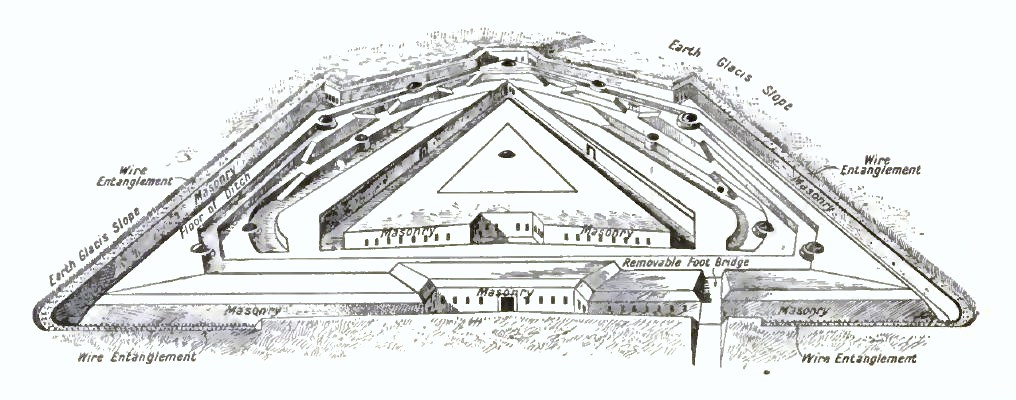

The detached forts were polygons of four or five sides in plan, with the front faces of the rampart angled at 95°. The rear or gorge of the fort was closed with a masonry wall, sufficient to repel a surprise infantry attack but easily demolished by the defenders' artillery should the fort be captured by the attackers. In the centre of the gorge wall was a

The detached forts were polygons of four or five sides in plan, with the front faces of the rampart angled at 95°. The rear or gorge of the fort was closed with a masonry wall, sufficient to repel a surprise infantry attack but easily demolished by the defenders' artillery should the fort be captured by the attackers. In the centre of the gorge wall was a reduit

A reduit is a fortified structure such as a citadel or a keep into which the defending troops can retreat when the outer defences are breached. The term is also used to describe an area of a country, which, through a ring of heavy fortifications ...

or keep, provided with casemates for guns which could fire over the rampart or along the flanks to support the next forts in the chain. The original bastioned encientes of these fortresses were initially retained or even rebuilt so as to prevent an attacker from infiltrating between the outlying forts and taking the fortress by a ''coup de main

A ''coup de main'' (; plural: ''coups de main'', French for blow with the hand) is a swift attack that relies on speed and surprise to accomplish its objectives in a single blow.

Definition

The United States Department of Defense defines it as ...

''. It was later thought by some engineers that a simple entrenchment would suffice or that no inner defence was necessary; the issue remained a debating point for some decades. In any case, few European cities undergoing the rapid expansion caused by the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

would willingly accept the restriction to their growth caused by a continuous line of ramparts. Aster insisted that his new technique was "not to be regarded... as a particular system" but this type of ring fortress became known as the Prussian System. Austrian engineers adopted a similar approach although differing in some details; the Prussian System and the Austrian System were together known as the German System.

Lessons of the Crimean War

The Crimean War (October 1853 to February 1856) was fought by theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, France, Britain and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

. Russian fortifications, which included some modern advances, were tested against the latest British and French artillery. At Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, the focus of the allied effort, the Russians had planned a modern fortress but little work had been done and earthworks were rapidly constructed instead. The largest and most complex earthwork, the Great Redan, was found to be largely resistant to British bombardments and difficult to carry by assault. Only one stone casemated work, the Malakoff Tower

Malakoff Tower ( pt, Torre Malakoff) is a tower located in Recife Antigo, Recife. This monument was built between 1835 and 1855 to be used as an observatory and as the main entrance and gateway for ''Arsenal da Marinha'' (Navy Arsenals) square ...

, had been completed at the time of the allied landing and proved impervious to bombardment but was finally carried by French infantry in a ''coup de main

A ''coup de main'' (; plural: ''coups de main'', French for blow with the hand) is a swift attack that relies on speed and surprise to accomplish its objectives in a single blow.

Definition

The United States Department of Defense defines it as ...

''. In the Battle of Kinburn (1855)

The Battle of Kinburn, a combined land-naval engagement during the final stage of the Crimean War, took place on the tip of the Kinburn Peninsula (on the south shore of the Dnieper–Bug estuary in what is now Ukraine) on 17 October 1855. Duri ...

, an Anglo-French fleet undertook a bombardment of the Russian fortress which guarded the mouth of the Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

. The most successful weapon there was the Paixhans gun

The Paixhans gun (French: ''Canon Paixhans'', ) was the first naval gun designed to fire explosive shells. It was developed by the French general Henri-Joseph Paixhans in 1822–1823. The design furthered the evolution of naval artillery into th ...

which was mounted on ironclad floating batteries

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

. These guns were the first to be able to fire explosive shells on a low trajectory and were able to devastate the open ramparts of the forts, causing their surrender within four hours. British attempts to subdue the casemated Russian forts at Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

and other fortifications in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

using conventional naval guns were far less successful.

Impact of rifled artillery

The first

The first rifled artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, ...

designs were developed independently during the 1840s and 1850s by several engineers in Europe. These weapons offered greatly increased range, accuracy and penetrating power over smooth-bore guns then in use. The first effective use of rifled guns was during the Second Italian War of Independence

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859 ( it, Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana; french: Campagne d'Italie), was fought by the Second French Empire and t ...

in 1859, when the French used them against the Austrians. The Austrians quickly realised that the outlying forts of their ring fortresses were now too close to prevent an enemy from bombarding a besieged town and at Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, they added a second circle of forts, about forward of the existing ring.

The British were apprehensive about a French invasion and in 1859 appointed the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom to fortify the naval dockyard

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that u ...

s of southern England. The experts on the commission, led by Sir William Jervois

Lieutenant General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois (10 September 1821 – 17 August 1897) was a British military engineer and diplomat. After joining the British Army in 1839, he saw service, as a second captain, in South Africa. In 18 ...

, interviewed Sir William Armstrong, a major developer and manufacturer of rifled artillery and were able to incorporate his advice into their designs. The ring forts at Plymouth and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

were set further out than the Prussian designs they were based on and the casemates of coastal batteries were protected by composite armoured shields, tested to be resistant to the latest heavy projectiles.

In the United States, it had been decided at an early stage that it would be impractical to provide landward fortifications for rapidly expanding cities but a considerable investment had been made in seaward defences in the form of multi-tiered casemated batteries, originally based on Montalembert's designs. During the

In the United States, it had been decided at an early stage that it would be impractical to provide landward fortifications for rapidly expanding cities but a considerable investment had been made in seaward defences in the form of multi-tiered casemated batteries, originally based on Montalembert's designs. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

of 1861 to 1865, the exposed masonry of these coastal batteries was found to be vulnerable to modern rifled artillery; Fort Pulaski

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

was quickly breached by only ten of these guns. On the other hand, the hastily constructed earthworks of landward fortifications proved much more resilient; the garrison of Fort Wagner

Fort Wagner or Battery Wagner was a beachhead fortification on Morris Island, South Carolina, that covered the southern approach to Charleston Harbor. It was the site of two American Civil War battles in the campaign known as Operations Again ...

were able to hold out for 58 days behind ramparts built of sand.

In France the military establishment clung to the concept of the bastion system. Between 1841 and 1844, an immense bastioned trace, the Thiers Wall

The Thiers wall (''Enceinte de Thiers'') was the last of the defensive walls of Paris. It was an enclosure constructed between 1841 and 1846 and was proposed by the French prime minister Adolphe Thiers but was actually implemented by his succe ...

, was built around Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. It was a single rampart long reinforced by 94 bastions. The main approaches to the city were further defended by several outlying bastioned forts, designed for all-round defence but not sited to be mutually supporting. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the invading Prussians were able to surround Paris after taking some of the outer forts and then bombard the city and its population with their rifled siege guns, without the need for a costly assault.

In the aftermath of defeat, the French belatedly adopted a version of the polygonal system in a huge programme of fortification which commenced in 1874, under the direction of General Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières

Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières (20 May 1815 – 16 February 1895) was a French military engineer and general whose ideas revolutionized the design of fortifications in France. He gave his name to the Séré de Rivières system of fortificatio ...

. Polygonal forts typical of the Séré de Rivières system

The system was named after Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières, its originator. The system was an ensemble of fortifications built from 1874 along the frontiers and coasts of France. The fortresses were obsolescent by 1914 but were used during ...

had guns protected by iron armour

Iron armour was a type of naval armour used on warships and, to a limited degree, fortifications. The use of iron gave rise to the term ironclad as a reference to a ship 'clad' in iron. The earliest material available in sufficient quantities for ...

or revolving Mougin turret

The Mougin turret is a land-based revolving gun turret that housed some of the heaviest armament in French fortifications of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While not reliably resistant to the explosive shells of opposing artillery, Mougi ...

s. The vulnerable masonry of the accommodation casemates were built facing away from an opponent, protected overhead by large mounds of earth, deep. The programme involved the building of ring fortresses around Paris and to guard border crossings, often surrounding Vauban-era fortifications; the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to the Prussians created the need for a new defensive zone, described as a "barrier of iron". Similar forts were also being built in Germany designed Hans Alexis von Bichler.

The "torpedo-shell crisis"

From the mid-19th century, chemists produced the first

From the mid-19th century, chemists produced the first high explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An ...

compounds, as opposed to low explosives such as gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

. The first of these, nitroglycerine

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating ...

and from 1867, dynamite, proved to be too unstable to be fired from a gun without exploding in the barrel. In 1885, the French chemist Eugène Turpin

François Eugène Turpin (30 September 1848 – 24 January 1927) was a French chemist involved in research of explosive materials. He lived in Colombes.

Biography

In 1881 Turpin proposed panclastites, a class of Sprengel explosives based on a mix ...

, patented a form of picric acid, which proved stable enough to be used as a blasting charge in artillery shells. These shells had recently evolved from the traditional sphere of iron into a pointed cylinder, at that time known as a "torpedo-shell". The combination of these, combined with new delayed-action fuzes, meant that shells could bury themselves deep under the surface of a fort and then explode with unprecedented force. The realisation that this new technology made even the most modern forts vulnerable was known as the "torpedo-shell crisis". The great powers of continental Europe were forced into vastly expensive programmes of fortification building and rebuilding to designs that were calculated to counter this latest threat.

In France, the recently completed forts began to be refurbished, with thick layers of concrete reinforcing the ramparts and the roofs of magazines and accommodation spaces. The Belgians had not started their new fortifications when the effectiveness of the new munitions became known and their chief engineer, Henri Alexis Brialmont

Henri-Alexis Brialmont (Venlo, 25 May 1821 – Brussels, 21 July 1903), nicknamed The Belgian Vauban after the French military architect, was a Belgian army officer, politician and writer of the 19th century, best known as a military archi ...

, was able to incorporate countermeasures in his design. Brialmont forts were triangular in plan and made extensive use of concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

with the main armament mounted in rotating turrets connected by tunnels. The French and Belgians assumed that the new forts must be able to withstand siege guns up to a calibre of as this was the largest mobile weapon in use. In Germany, after updating their Bichler forts with layers of sand and concrete and building others in the style of Brialmont, a new design emerged, in which fort artillery and infantry positions would be dispersed in the landscape, connected only by trenches or tunnels and without a continuous enciente. This type of fortified position was called a and was the result of the work of several German theorists but came to fruition under Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz

Wilhelm Leopold Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz (12 August 1843 – 19 April 1916), also known as ''Goltz Pasha'', was a Prussian Field Marshal and military writer.

Military career

Goltz was born in , East Prussia (later renamed Goltzhausen; now ...

who was appointed Inspector-General of Fortifications in 1898.

World Wars

First World War

At the start of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, the German Army crossed into neutral Belgium with the object of outflanking the French border fortifications. In their path was the fortified position of Liège

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, a ring fortress built by Brialmont with a circumference of which the Germans reached on 4 August. Repeated attempts to pass massed infantry through the intervals between the forts resulted in the capture of the city of Liège on 7 August, at the cost of 47,500 German casualties but without any of the forts being taken. The forts were only subdued by the arrival of super-heavy 42 cm Gamma Mörser

The 42 cm ''kurze Marinekanone'' L/12, or ''Gamma-Gerät'' ("Gamma Device"), was a German siege gun built by Krupp. The ''Gamma-Gerät''s barrel diameter was , making it one of the largest artillery pieces ever fielded. The ''Gamma-Gerät ...

siege howitzers and other large weapons, which were capable of smashing the armoured turrets and penetrating the concrete living spaces; the last fort surrendering on 16 August. The fortified position of Namur was demolished in the same fashion a few days later and that at Antwerp only survived for longer because fewer resources were directed against it.

On the Eastern Front, most polygonal fortifications were also quickly overcome by heavy artillery. The

On the Eastern Front, most polygonal fortifications were also quickly overcome by heavy artillery. The Kaunas Fortress

Kaunas Fortress ( lt, Kauno tvirtovė, russian: Кοвенская крепость, german: Festung Kowno) is the remains of a fortress complex in Kaunas, Lithuania. It was constructed and renovated between 1882 and 1915 to protect the Russian ...

(now in Lithuania) was the most expensive fortification in the Russian Empire, but a modernisation programme was incomplete. In July 1915, German assaults concentrated on three un-modernised forts in the southwest sector. Following the loss of these forts the garrison abandoned the entire fortress, prompted by the desertion of their commanding officer on the previous day, the assault having lasted only eleven days. Another Russian ring fortress at Novogeorgievsk, later renamed Modlin, which guarded the northern approach to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, fell after Siege of Novogeorgievsk, a siege of 10 days in August 1915, with the loss of 90,000 men taken prisoner and 1,600 guns. The largest Austro-Hungarian fortification was Przemyśl Fortress which protected the province of Eastern Galicia and had a ring of twenty five modern polygonal forts. An invading Russian army besieged the fortress, but initially lacked heavy artillery and were short of ammunition for their field guns. An initial infantry assault in September 1914 was repulsed with heavy Russian losses, but the fortress was finally surrendered in the following March, after both a relief attempt and a Breakout (military), breakout had failed.

Following these failures, the French high command concluded that fixed fortifications were obsolete and they began the process of disarming their forts, since there was a grave shortage of medium artillery pieces in their field armies. In February 1916, the Germans began the Battle of Verdun, hoping to force the French to squander their forces in costly counter-attacks in an effort to regain it. They found that the Verdun forts, which had been recently upgraded with extra layers of concrete and sand, were resistant to their heaviest shells. Fort Douaumont was captured, almost by accident, by a small party of Germans who climbed through an unattended embrasure, the rest of the forts could not permanently be subdued and the offensive was eventually called off in July after huge casualties on both sides.

Following these failures, the French high command concluded that fixed fortifications were obsolete and they began the process of disarming their forts, since there was a grave shortage of medium artillery pieces in their field armies. In February 1916, the Germans began the Battle of Verdun, hoping to force the French to squander their forces in costly counter-attacks in an effort to regain it. They found that the Verdun forts, which had been recently upgraded with extra layers of concrete and sand, were resistant to their heaviest shells. Fort Douaumont was captured, almost by accident, by a small party of Germans who climbed through an unattended embrasure, the rest of the forts could not permanently be subdued and the offensive was eventually called off in July after huge casualties on both sides.

Inter-war developments

After the war, the apparent success of the Verdun forts led the French government to re-fortify the eastern border. Rather than build new polygonal forts, the method chosen was a developed version of the German system of dispersed strongpoints connected by tunnels to a central underground barracks, all concealed in the landscape. This concept known to the French as because the elements of the fort were analogous to the fingers of a hand. The system became known as the Maginot Line, after the French Minister of War, who had initiated the project in 1930. Where the Maginot Line coincided with Séré de Rivières forts, new concrete casemates were constructed inside the old works.Kaufmann, Kaufmann & Lang, p. 208 In Belgium, a series of commissions decided that a new line of fortifications should be constructed at Liège, while some of the old forts there should be modernised. Three new forts were constructed which were developed forms of the old Brialmont polygonal forts. The fourth and largest, Fort Eben-Emael, had its enciente defined by the great cutting of the Albert Canal.Second World War

The war opened with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; by 13 September, Warsaw and the partly-modernised fortress of Modlin had been surrounded. The fortress was separated from Warsaw on 22 September and despite numerous German infantry assaults supported by heavy artillery and dive bombing, Modlin was not surrendered until 29 September after receiving the news that Warsaw had fallen.

On 10 May 1940, German forces attacked the new Belgian forts, quickly Battle of Fort Eben-Emael, neutralising Eben-Emael by airborne assault. The three other forts were bombarded by Skoda 305 mm Model 1911, 305 mm howitzers and dive-bombers and each repulsed several infantry assaults. Two of the forts surrendered on 21 May and the last, Fort de Battice, on the following day, having been by-passed by the main German thrust. Modernised French polygonal forts at Maubeuge were attacked on 19 May and were surrendered after their gun turrets and observation domes had been knocked out with anti-tank guns and demolition charges. Late in the war, the ring fortifications of Metz were hastily prepared for defence by German forces and was attacked by the United States Army Central, Third Army in mid-September 1944 in the Battle of Metz; the last fort surrendered nearly three months later.Zaloga, p. 70

The war opened with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939; by 13 September, Warsaw and the partly-modernised fortress of Modlin had been surrounded. The fortress was separated from Warsaw on 22 September and despite numerous German infantry assaults supported by heavy artillery and dive bombing, Modlin was not surrendered until 29 September after receiving the news that Warsaw had fallen.

On 10 May 1940, German forces attacked the new Belgian forts, quickly Battle of Fort Eben-Emael, neutralising Eben-Emael by airborne assault. The three other forts were bombarded by Skoda 305 mm Model 1911, 305 mm howitzers and dive-bombers and each repulsed several infantry assaults. Two of the forts surrendered on 21 May and the last, Fort de Battice, on the following day, having been by-passed by the main German thrust. Modernised French polygonal forts at Maubeuge were attacked on 19 May and were surrendered after their gun turrets and observation domes had been knocked out with anti-tank guns and demolition charges. Late in the war, the ring fortifications of Metz were hastily prepared for defence by German forces and was attacked by the United States Army Central, Third Army in mid-September 1944 in the Battle of Metz; the last fort surrendered nearly three months later.Zaloga, p. 70

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{fortifications Fortifications by type Warfare of the late modern period Fortification (architectural elements) French inventions