The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (''Polsky front'', Polish Front) (late autumn 1918 / 14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was primarily fought between the

Second Polish Republic and the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

in the aftermath of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the

Russian Revolution, on territories which were formerly held by the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

and the

Austro-Hungarian Empire.

On 13 November 1918, after the collapse of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

and the

Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

,

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

's

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

annulled the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

(which it had signed with the Central Powers in March 1918) and started moving forces in the western direction to recover and secure the ''

Ober Ost'' regions vacated by the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

forces that the Russian state had lost under the treaty. Lenin saw the newly independent

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

(formed in October–November 1918) as the bridge which his

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

would have to cross to assist other

communist movements and to bring about more

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an revolutions. At the same time, leading Polish politicians of different orientations pursued the general expectation of restoring the country's

pre-1772 borders. Motivated by that idea, Polish

Chief of State Józef Piłsudski (in office from 14 November 1918) began moving troops east.

In 1919, while the Soviet Red Army was still preoccupied with the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

of 1917–1922, the

Polish Army took most of

Lithuania and

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

. By July 1919, Polish forces had taken control of much of

Western Ukraine and had emerged victorious from the

Polish–Ukrainian War of November 1918 to July 1919. In the eastern part of

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

bordering on

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

,

Symon Petliura tried to defend the

Ukrainian People's Republic, but as the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, they

advanced westward towards the disputed Ukrainian lands and made Petliura's forces retreat. Reduced to a small amount of territory in the west, Petliura was compelled to seek an

alliance with Piłsudski, officially concluded in April 1920.

Piłsudski believed that the best way for Poland to secure favorable borders was by military action and that he could easily defeat the Red Army forces. His

Kiev Offensive commenced in late April 1920 and resulted in the takeover of

Kiev by the Polish and allied Ukrainian forces on 7 May. The Soviet armies in the area, which were weaker, had not been defeated, as they avoided major confrontations and withdrew.

The Red Army responded to the Polish offensive with counterattacks: from 5 June on the southern Ukrainian front and from 4 July on the northern front. The Soviet operation pushed the Polish forces back westward all the way to

Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

, the Polish capital, while the

Directorate of Ukraine fled to

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Fears of Soviet troops arriving at the German borders increased the

interest and involvement of the Western powers in the war. In mid-summer the fall of Warsaw seemed certain but in mid-August the tide had turned again after the Polish forces achieved an unexpected and decisive victory at the

Battle of Warsaw (12 to 25 August 1920). In the wake of the

eastward Polish advance that followed, the Soviets sued for peace, and the war ended with a ceasefire on 18 October 1920.

The

Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet Wa ...

, signed on 18 March 1921, divided the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia. The war and the treaty negotiations determined the Soviet–Polish border for the rest of the

interwar period. Poland's eastern border was established at about 200 km east of the

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, ...

(a 1920

British proposal for Poland's border, based on the version approved in 1919 by the

Entente leaders as the limit of Poland's expansion in the eastern direction). Ukraine and

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

became divided between Poland and Soviet Russia, which established the respective

Soviet republics in its areas of the territory.

The peace negotiations – on the Polish side conducted chiefly by Piłsudski's opponents and against his will – ended with the official recognition of the two Soviet republics, which became parties to the treaty. This outcome and the new border agreed on precluded any possibility of the formation of the ''

Intermarium'' Polish-led federation of states that Piłsudski had envisaged or of meeting his other eastern-policy goals. The

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

,

established in December 1922, later used the

Ukrainian Soviet Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Republic (russian: Украинская Советская Республика, translit= Ukrainskaya Sovetskaya Respublika) was one of the earlier Soviet Ukrainian quasi-state formations (Ukrainian People's Republic of S ...

and the

Byelorussian Soviet Republic

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

to

claim their unification with parts of the ''

Kresy'' territories where

East Slavic people outnumbered ethnic

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...

and had remained, after the Peace of Riga, on the Polish side of the border, lacking any form of autonomy.

Names and dates

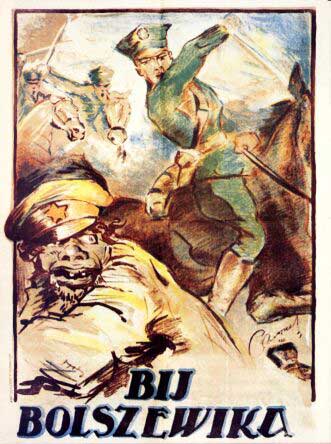

The war is known by several names. "Polish–Soviet War" is the most common but other names include "Russo–Polish War" (or "Polish–Russian War") and "Polish–Bolshevik War".

This last term (or just "Bolshevik War" ( pl, Wojna bolszewicka)) is most common in Polish sources. In some Polish sources it is also referred as the "War of 1920" ( pl, Wojna 1920 roku).

[For example: 1) ''Sąsiedzi wobec wojny 1920 roku. Wybór dokumentów.'']

2) ''Wojna 1920 roku na Mazowszu i Podlasiu''

3) ''Nad Wisłą i Wkrą. Studium do polsko–radzieckiej wojny 1920 roku''

There is disagreement over the dates of the war. The ''

Encyclopædia Britannica'' begins its "Russo-Polish War" article with the date range 1919–1920 but then states, "Although there had been hostilities between the two countries during 1919, the conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May." Some Western historians, including

Norman Davies, consider mid-February 1919 the beginning of the war. However, military confrontations between forces that can be considered officially Polish and the Red Army took place already in late autumn 1918 and in January 1919. The city of

Vilnius, for example, was taken by the Soviets on 5 January 1919.

The ending date is given as either 1920 or 1921; this confusion stems from the fact that while the

ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

was put into force on 18 October 1920, the

official treaty ending the war was signed on 18 March 1921. While the events of late 1918 and 1919 can be described as a border conflict and only in spring 1920 did both sides engage in an all-out war, the warfare that took place in late April 1920 was an escalation of the fighting that began a year and a half earlier.

Background

The war's main territories of contention lie in what is now

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

and

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

. Until the mid-13th century, they formed part of the medieval state of

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

. After a period of internal wars and the 1240

Mongol invasion

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

, the lands became objects of expansion for the

Kingdom of Poland and for the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was Partitions of Poland, partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire, Habsburg Empire of ...

. In the first half of the 14th century, the

Principality of Kiev and the land between the

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

,

Pripyat, and

Daugava (Western Dvina) rivers became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1352, Poland and Lithuania divided the

Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia between themselves. In 1569, in accordance with the terms of the

Union of Lublin between Poland and Lithuania, some of the Ukrainian lands passed to the

Polish Crown. Between 1772 and 1795, many of the

East Slavic territories became part of the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in the course of the

Partitions of Poland–Lithuania. In 1795 (the

Third Partition of Poland), Poland lost formal independence. After the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

of 1814–1815, much of the territory of the

Duchy of Warsaw was transferred to Russian control and became the autonomous

Congress Poland (officially the Kingdom of Poland). After young Poles refused conscription to the

Imperial Russian Army during the

January Uprising of 1863, Tsar

Alexander II stripped Congress Poland of its separate constitution, attempted to force general use of the

Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living E ...

and took away vast tracts of land from Poles. Congress Poland was incorporated more directly into imperial Russia by being divided into ten provinces, each with an appointed Russian military governor and all under complete control of the Russian Governor-General at Warsaw.

In the

aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, n ...

, the map of

Central and Eastern Europe changed drastically. The

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

's defeat rendered obsolete

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

's plans for the creation of

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

an German-dominated states (''

Mitteleuropa''), which included another rendition of the

Kingdom of Poland. The

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

collapsed, which resulted in the

Russian Revolution and the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. The Russian state lost territory due to the

German offensive and the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

, signed by the emergent

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. Several nations of the region saw a chance for independence and seized their opportunity to gain it. With the defeat of Germany in the

Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

and the withdrawal of the

Imperial German Army in the

Eastern Front, Soviet Russia disavowed the treaty and proceeded to recover many of the former territories of the Russian Empire. However, preoccupied with the civil war, it did not have the resources to react swiftly to the national rebellions.

In November 1918, Poland became a

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined ter ...

. Among the several border wars fought by the

Second Polish Republic was the successful

Greater Poland uprising (1918–1919) Greater Poland Uprising (also Wielkopolska Uprising or Great Poland Uprising) may refer to a number of armed rebellions in the region of Greater Poland:

* Greater Poland Uprising (1794)

* Greater Poland Uprising (1806)

Greater Poland uprising ...

against

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. The historic

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

included vast territories in the east. They had been

incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1772–1795 and had remained its parts, as the

Northwest Territory, until

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

After the war they were contested by the

Polish,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

n,

Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

,

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

ian,

Lithuanian, and

Latvian interests.

In newly independent Poland, politics were strongly influenced by

Józef Piłsudski. On 11 November 1918, Piłsudski was made head of Polish armed forces by the

Regency Council of the

Kingdom of Poland, a body installed by the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

. Subsequently, he was recognized by many Polish politicians as temporary chief of state and exercised in practice extensive powers. Under the

Small Constitution of 20 February 1919, he became

chief of state. As such, he reported to the

Legislative Sejm.

With the collapse of the Russian and

German occupying authorities, virtually all of Poland's neighbours began fighting over borders and other issues. The

Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

, the

Estonian War of Independence

The Estonian War of Independence ( et, Vabadussõda, literally "Freedom War"), also known as the Estonian Liberation War, was a defensive campaign of the Estonian Army and its allies, most notably the United Kingdom, against the Bolshevik westw ...

, the

Latvian War of Independence, and the

Lithuanian Wars of Independence were all fought in the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

region.

Russia was overwhelmed by domestic struggles. In early March 1919, the

Communist International was established in

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. The

Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed in March and the

Bavarian Soviet Republic in April.

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, in a conversation with Prime Minister

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

, commented sarcastically: "The war of giants has ended, the wars of the pygmies begin."

The Polish–Soviet War was the longest lasting of the international engagements.

The territory of what had become Poland had been a major battleground during World War I and the new country lacked political stability. It had won the hard-fought

Polish–Ukrainian War against the

West Ukrainian People's Republic by July 1919 but had already become embroiled in new conflicts with Germany (the 1919–1921

Silesian Uprisings) and the January 1919

border conflict with Czechoslovakia. Meanwhile, Soviet Russia focused on thwarting the

counterrevolution

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

and the 1918–1925

intervention by the Allied powers. The first clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred in autumn and winter 1918/1919, but it took a year and a half for a full-scale war to develop.

The Western powers considered any significant territorial expansion of Poland, at the expense of Russia or Germany, to be highly disruptive to the post-World War I order. Among other factors, the Western Allies did not want to give the disgruntled Germany and Russia a reason to conspire together. The rise of the unrecognized

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

regime complicated this rationale.

The

Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, regulated Poland's western border. The

Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) had not made a definitive ruling in regard to Poland's eastern border but on 8 December 1919, the Allied

Supreme War Council issued a provisional boundary (its later version would be known as the

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, ...

). It was an attempt to define the areas that had an "indisputably Polish ethnic majority".

The permanent border was contingent on the Western powers' future negotiations with

White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

Russia, presumed to prevail in the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. Piłsudski and his allies blamed Prime Minister

Ignacy Paderewski for this outcome and caused his dismissal. Paderewski, embittered, withdrew from politics.

The leader of Russia's new Bolshevik government,

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, aimed to regain control of the territories abandoned by Russia in the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

in March 1918 (the treaty was annulled by Russia on 13 November 1918) and to set up

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

governments in the emerging countries in the

western parts of the former Russian Empire. The more ambitious goal was to also reach Germany, where he expected a

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

revolution to break out. He believed that Soviet Russia could not survive without the support of a socialist Germany.

By the end of summer 1919, the Soviets had taken over most of

eastern and

central Ukraine (formerly parts of the Russian Empire) and driven the

Directorate of Ukraine from

Kiev. In February 1919, they set up the

Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (Litbel). The government there was very unpopular because of the terror it had imposed and the collection of food and goods for the army.

Officially, the Soviet government denied charges of trying to invade Europe.

As the Polish–Soviet War progressed, particularly while Poland's

Kiev Offensive was being repelled in June 1920, Soviet policymakers, including Lenin, increasingly saw the war as the opportunity to spread the revolution westward.

[

From late 1919, Lenin, encouraged by the Red Army's civil war victories over the White Russian anti- communist forces and their Western allies, began to envision the future of world revolution with greater optimism. The Bolsheviks proclaimed the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat and agitated for a worldwide communist community. They intended to link the revolution in Russia with a communist revolution in Germany they had hoped for and to assist other communist movements in Europe. To be able to provide direct physical support to revolutionaries in the West, the Red Army would have to cross the territory of Poland.] According to Aviel Roshwald, (Piłsudski) "hoped to incorporate most of the territories of the defunct

According to Aviel Roshwald, (Piłsudski) "hoped to incorporate most of the territories of the defunct Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

into the future Polish state by structuring it as the Polish-led, multinational federation."imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

intentions of Russia or Germany. Piłsudski believed that there could be no independent Poland without a Ukraine free of Russian control, thus his main interest was in splitting Ukraine from Russia.Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, ...

, which contained a significant Polish minority.Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

and Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, deprived of land and mineral wealth of the South and South-east, Russia could easily move into the status of second-grade power. Poland, as the largest and strongest of the new states, could easily establish a sphere of influence stretching from Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

to the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

".National Democracy National Democracy may refer to:

* National Democracy (Czech Republic)

* National Democracy (Italy)

* National Democracy (Philippines)

* National Democracy (Poland)

* National Democracy (Spain)

See also

* Civic nationalism, a general concept

* ...

's idea of direct incorporation and Polonization of the disputed eastern lands,Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

were more rhetorical than real. Piłsudski had made many obfuscating statements, but never specifically stated his views regarding Poland's eastern borders or political arrangements he intended for the region.

Preliminary hostilities

From late 1917, Polish revolutionary military units were formed in Russia. They were combined into the Western Rifle Division in October 1918. In summer 1918, a short-lived Polish communist

Communism in Poland can trace its origins to the late 19th century: the Marxist First Proletariat party was founded in 1882. Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (''Socjaldemokracja Króles ...

government, led by Stefan Heltman, was created in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. Both the military and civilian structures were meant to facilitate the eventual introduction of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

into Poland in the form of a Polish Soviet Republic.

Given the precarious situation resulting from the withdrawal of German forces from Belarus and Lithuania and the expected arrival of the

Given the precarious situation resulting from the withdrawal of German forces from Belarus and Lithuania and the expected arrival of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

there, Polish Self-Defence had been organized in autumn 1918 around major concentrations of Polish population, such as Minsk, Vilnius and Grodno. They were based on the Polish Military Organisation and were recognized as part of the Polish Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Siły Zbrojne Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, abbreviated ''SZ RP''; popularly called ''Wojsko Polskie'' in Poland, abbreviated ''WP''—roughly, the "Polish Military") are the national armed forces of ...

by the decree of Polish Chief of State Piłsudski, issued on 7 December 1918.

The German of '' Ober Ost'' declared on 15 November that its authority in Vilnius would be transferred to the Red Army.

In late autumn 1918, the Polish 4th Rifle Division fought the Red Army in Russia. The division operated under the authority of the Polish Army in France and General Józef Haller. Politically, the division fought under the Polish National Committee (KNP), recognized by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

as a temporary government of Poland. In January 1919, per Piłsudski's decision, the 4th Rifle Division became part of the Polish Army.

The Polish Self-Defence forces were defeated by the Soviets at a number of locations. Minsk was taken by the Russian Western Army on 11 December 1918. The Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia was declared there on 31 December. After three days of heavy fighting with the Western Rifle Division, the Self-Defence units withdrew from Vilnius on 5 January 1919. Polish–Soviet skirmishes continued in January and February.

The Polish armed forces were hurriedly formed to fight in several border wars. Two major formations manned the Russian front in February 1919: the northern, led by General Wacław Iwaszkiewicz-Rudoszański, and the southern, under General Antoni Listowski

Antoni Listowski (29 March 1865, Warsaw - 13 September 1927, Warsaw) was a Polish military officer. After being a mayor general of the Imperial Russian Army (from 1916 on), he became general in the Polish Armed Forces and took part in the Polish ...

.

Polish–Ukrainian War

On 18 October 1918, the Ukrainian National Council was formed in Eastern Galicia, still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; it was led by Yevhen Petrushevych. The establishment of a Ukrainian state there was proclaimed in November 1918; it had become known as the West Ukrainian People's Republic and it claimed Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

as its capital. Key buildings in Lviv were seized by the Ukrainians on 31 October 1918. On 1 November, Polish residents of the city counterattacked and the Polish–Ukrainian War began.

Key buildings in Lviv were seized by the Ukrainians on 31 October 1918. On 1 November, Polish residents of the city counterattacked and the Polish–Ukrainian War began.France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. It consisted of over 67,000 well-equipped and highly trained soldiers. The Blue Army helped drive the Ukrainian forces east past the Zbruch

The Zbruch ( uk, Збруч, pl, Zbrucz) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.[Збруч< ...]

River and decisively contributed to the outcome of the war. The West Ukrainian People's Republic was defeated by mid-July and eastern Galicia had come under Polish administration.

Polish intelligence

Jan Kowalewski

Lt. Col. Jan Kowalewski (23 October 1892 – 31 October 1965) was a Polish cryptologist, intelligence officer, engineer, journalist, military commander, and creator and first head of the Polish Cipher Bureau. He recruited a large staff of crypt ...

, a polyglot and amateur cryptographer, broke the codes and ciphers of the army of the West Ukrainian People's Republic and of General Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

's White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

Russian forces.University of Warsaw

The University of Warsaw ( pl, Uniwersytet Warszawski, la, Universitas Varsoviensis) is a public university in Warsaw, Poland. Established in 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country offering 37 different fields of ...

and the University of Lviv (most notably the founders of the Polish School of Mathematics – Stanisław Leśniewski, Stefan Mazurkiewicz

Stefan Mazurkiewicz (25 September 1888 – 19 June 1945) was a Polish mathematician who worked in mathematical analysis, topology, and probability. He was a student of Wacław Sierpiński and a member of the Polish Academy of Learning (''PAU''). ...

and Wacław Sierpiński

Wacław Franciszek Sierpiński (; 14 March 1882 – 21 October 1969) was a Polish mathematician. He was known for contributions to set theory (research on the axiom of choice and the continuum hypothesis), number theory, theory of functions, and to ...

), who succeeded in breaking the Soviet Russian ciphers as well. During the Polish–Soviet War, the Polish decryption of Red Army radio messages made it possible to use Polish military forces efficiently against Soviet Russian forces and to win many individual battles, most importantly the Battle of Warsaw.

War

Early progression of the conflict

On 5 January 1919, the

On 5 January 1919, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

took Vilnius, which led to the establishment of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (Litbel) on 28 February.Antoni Listowski

Antoni Listowski (29 March 1865, Warsaw - 13 September 1927, Warsaw) was a Polish military officer. After being a mayor general of the Imperial Russian Army (from 1916 on), he became general in the Polish Armed Forces and took part in the Polish ...

, near Byaroza, Belarus.Neman

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ; ...

River, took Pinsk on 5 March and reached the outskirts of Lida

Lida ( be, Лі́да ; russian: Ли́да ; lt, Lyda; lv, Ļida; pl, Lida ; yi, לידע, Lyde) is a city 168 km (104 mi) west of Minsk in western Belarus in Grodno Region.

Etymology

The name ''Lida'' arises from its Lithu ...

; on 4 March, Piłsudski ordered further movement to the east stopped. The Soviet leadership had become preoccupied with the issue of providing military assistance to the Hungarian Soviet Republic and with the Siberian offensive of the White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

, led by Alexander Kolchak.

Fighting the Polish–Ukrainian War, by July 1919 Polish armies eliminated the West Ukrainian People's Republic. Secretly preparing an assault on Soviet-held Vilnius, in early April Piłsudski was able to shift some of the forces used in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

to the northern front. The idea was to create a ''fait accompli'' and to prevent the Western powers from granting the territories claimed by Poland to White movement's Russia (the Whites were expected to prevail in the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

).

A new Polish offensive started on 16 April.

A new Polish offensive started on 16 April.Lida

Lida ( be, Лі́да ; russian: Ли́да ; lt, Lyda; lv, Ļida; pl, Lida ; yi, לידע, Lyde) is a city 168 km (104 mi) west of Minsk in western Belarus in Grodno Region.

Etymology

The name ''Lida'' arises from its Lithu ...

on 17 April, Novogrudok on 18 April, Baranavichy

Baranavichy ( ; be, Бара́навічы, Łacinka: , ; russian: Бара́новичи; yi, באַראַנאָוויטש; pl, Baranowicze) is a city in the Brest Region of western Belarus, with a population (as of 2019) of 179,000. It is no ...

on 19 April and Grodno on 28 April. Piłsudski's group entered Vilnius on 19 April and captured the city after two days of fighting.Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was Partitions of Poland, partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire, Habsburg Empire of ...

" on 22 April. It was sharply criticized by his rival National Democrats, who demanded direct incorporation of the former Grand Duchy lands by Poland and signaled their opposition to Piłsudski's territorial and political concepts. Piłsudski had thus proceeded to restore the historic territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

by military means, leaving the necessary political determinations for later.Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

commander to reclaim Vilnius as soon as possible. The Red Army formations that attacked the Polish forces were defeated by Edward Rydz-Śmigły's units between 30 April and 7 May. While the Poles extended their holdings further, the Red Army, unable to accomplish its objectives and facing intensified combat with the White forces elsewhere, withdrew from its positions.

The Polish "Lithuanian–Belarusian Front" was established on 15 May and placed under command of General Stanisław Szeptycki.

In a statute passed on 15 May, Polish Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

called for the inclusion of the eastern borderline nations in the Polish state as autonomous entities. It was intended to make a positive impression on the participants of the Paris Peace Conference. At the conference, Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ignacy Paderewski declared Poland's support for self-determination of the eastern nations, in line with Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's doctrine and in an effort to secure Western support for Poland's policies in regard to Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania.

The Polish offensive was discontinued around the line of German trenches and fortifications from World War I, because of high likelihood of Poland's war with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

over territorial and other issues. Half of Poland's military strength had been concentrated on the German front by mid-June. The offensive in the east was resumed at the end of June, following the Treaty of Versailles. The treaty, signed and ratified by Germany, preserved the '' status quo'' in western Poland.

On the southern front in Volhynia, in May and in July the Polish forces confronted the Red Army, which was in process of pushing Petliura's Ukrainian units out of the contested territories. The rural Orthodox population there was hostile to the Polish authorities and actively supported the Bolsheviks. Also in Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-centra ...

and near the eastern reaches of Galicia, the Polish armies kept slowly advancing to the east until December. They crossed the Zbruch

The Zbruch ( uk, Збруч, pl, Zbrucz) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.[Збруч< ...]

River and displaced Soviet forces from a number of localities.

The Polish forces took Minsk on 8 August.

The Polish forces took Minsk on 8 August.tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

s were deployed for the first time and the town of Babruysk was captured.Barysaw

Barysaw ( be, Барысаў, ) or Borisov (russian: Борисов, ) is a city in Belarus near the Berezina River in the Minsk Region 74 km north-east from Minsk. Its population is around 145,000.

History

Barysaw is first mentioned in ...

was taken on 10 September and parts of Polotsk on 21 September. By mid-September, the Poles secured the region along the Daugava from the Dysna River to Daugavpils.Polesia

Polesia, Polesie, or Polesye, uk, Полісся (Polissia), pl, Polesie, russian: Полесье (Polesye) is a natural and historical region that starts from the farthest edge of Central Europe and encompasses Eastern Europe, including East ...

and Volhynia; along the Zbruch

The Zbruch ( uk, Збруч, pl, Zbrucz) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.[Збруч< ...]

River it reached the Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

** Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditiona ...

border. A Red Army assault between the Daugava and Berezina Rivers was repelled in October and the front had become relatively inactive with sporadic encounters only, as the line designated by Piłsudski to be the goal of the Polish operation in the north was reached.

In autumn 1919, the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

voted to incorporate into Poland the conquered territories up to the Daugava and Berezina Rivers, including Minsk.

The Polish successes in summer 1919 resulted from the fact that the Soviets prioritized the warfare with the White forces, which was more crucial for them. The successes created an illusion of Polish military prowess and Soviet weakness.Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

and known as the Volunteer Army, marched on Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. Piłsuski refused to join the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War because he considered the Whites more threatening to Poland than the Bolsheviks.nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, and its partnership with Western politics.Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky ( rus, Михаил Николаевич Тухачевский, Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevskiy, p=tʊxɐˈtɕefskʲɪj; – 12 June 1937) nicknamed the Red Napoleon by foreign newspapers, was a Sovie ...

later commented on the likely disastrous consequences for the Bolsheviks if the Polish government undertook military cooperation with Denikin at the time of his advance on Moscow. In a book he later published, Denikin pointed at Poland as the savior of the Bolshevik power.

Denikin twice appealed to Piłsudski for help, in summer and in autumn 1919. According to Denikin, "The defeat of the south of Russia will make Poland face the power that will become a calamity for the Polish culture and will threaten the existence of the Polish state". According to Piłsudski, "The lesser evil is to facilitate a White Russia's defeat by Red Russia. ... With any Russia, we fight for Poland. Let all that filthy West talk all they want; we're not going to be dragged into and used for the fight against the Russian revolution. Quite to the contrary, in the name of permanent Polish interests, we want to make it easier for the revolutionary army to act against the counter-revolutionary army." On 12 December, the Red Army pushed Denikin out of Kiev.

The self-perceived interests of Poland and White Russia were irreconcilable. Piłsudski wanted to break up Russia and create a powerful Poland. Denikin, Alexander Kolchak and

Denikin twice appealed to Piłsudski for help, in summer and in autumn 1919. According to Denikin, "The defeat of the south of Russia will make Poland face the power that will become a calamity for the Polish culture and will threaten the existence of the Polish state". According to Piłsudski, "The lesser evil is to facilitate a White Russia's defeat by Red Russia. ... With any Russia, we fight for Poland. Let all that filthy West talk all they want; we're not going to be dragged into and used for the fight against the Russian revolution. Quite to the contrary, in the name of permanent Polish interests, we want to make it easier for the revolutionary army to act against the counter-revolutionary army." On 12 December, the Red Army pushed Denikin out of Kiev.

The self-perceived interests of Poland and White Russia were irreconcilable. Piłsudski wanted to break up Russia and create a powerful Poland. Denikin, Alexander Kolchak and Nikolai Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolayevich Yudenich ( – 5 October 1933) was a commander of the Russian Imperial Army during World War I. He was a leader of the anti-communist White movement in Northwestern Russia during the Civil War.

Biography

Early life

Yude ...

wanted territorial integrity for the "one, great and indivisible Russia". Piłsudski held the Bolshevik military forces in low regard and thought of Red Russia as easy to defeat. The victorious in the civil war communists were going to be pushed far to the east and deprived of Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic lands, and the southern Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

; they would no longer constitute a threat to Poland.

From the beginning of the conflict, many peace initiatives had been declared by the Polish and Russian sides, but they were intended as cover or stalling for time, as each side concentrated on military preparations and moves. One series of Polish-Soviet negotiations commenced in Białowieża after the termination of the summer 1919 military activities; they were moved in early November 1919 to Mikashevichy. The only exception to the Polish policy of front stabilization since autumn 1919 was the winter attack on Daugavpils. Edward Rydz-Śmigły's previous attempts to capture the city in summer and early autumn had been unsuccessful. A secret political and military pact regarding a common attack on Daugavpils was signed between representatives of Poland and the Latvian Provisional Government on 30 December. On 3 January 1920, Polish and Latvian forces (30,000 Poles and 10,000 Latvians) commenced a joint operation against the surprised enemy. The Bolshevik 15th Army withdrew and had not been pursued; the fighting terminated on 25 January. The taking of Daugavpils was accomplished primarily by the 3rd Legions Infantry Division under Rydz-Śmigły.

The only exception to the Polish policy of front stabilization since autumn 1919 was the winter attack on Daugavpils. Edward Rydz-Śmigły's previous attempts to capture the city in summer and early autumn had been unsuccessful. A secret political and military pact regarding a common attack on Daugavpils was signed between representatives of Poland and the Latvian Provisional Government on 30 December. On 3 January 1920, Polish and Latvian forces (30,000 Poles and 10,000 Latvians) commenced a joint operation against the surprised enemy. The Bolshevik 15th Army withdrew and had not been pursued; the fighting terminated on 25 January. The taking of Daugavpils was accomplished primarily by the 3rd Legions Infantry Division under Rydz-Śmigły.

Abortive peace process

In late autumn 1919, to many Polish politicians it appeared that Poland had achieved strategically desirable borders in the east and therefore fighting the Bolsheviks should be terminated and peace negotiations should commence. The pursuit of peace dominated also popular sentiments and anti-war demonstrations had taken place.

The leadership of Soviet Russia confronted at that time a number of pressing internal and external problems. In order to effectively address the difficulties, they wanted to stop the warfare and offer peace to their neighbors, hoping to be able to come out of the international isolation they had been subjected to. Courted by the Soviets, the potential allies of Poland ( Lithuania, Latvia,

In late autumn 1919, to many Polish politicians it appeared that Poland had achieved strategically desirable borders in the east and therefore fighting the Bolsheviks should be terminated and peace negotiations should commence. The pursuit of peace dominated also popular sentiments and anti-war demonstrations had taken place.

The leadership of Soviet Russia confronted at that time a number of pressing internal and external problems. In order to effectively address the difficulties, they wanted to stop the warfare and offer peace to their neighbors, hoping to be able to come out of the international isolation they had been subjected to. Courted by the Soviets, the potential allies of Poland ( Lithuania, Latvia, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, or the South Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

states) were unwilling to join a Polish-led anti-Soviet alliance. Faced with the diminishing revolutionary fervor in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, the Soviets were inclined to delay their hallmark project, a Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

republic of Europe, to some indefinite future.

The peace offers sent to Warsaw by Russia's Foreign Secretary Georgy Chicherin and other Russian governing institutions between late December 1919 and early February 1920 had not been responded to. The Soviets proposed a favorable for Poland troop demarcation line consistent with the current military frontiers, leaving permanent border determinations for later.

While the Soviet overtures generated considerable interests on the parts on the socialist, agrarian and nationalist political camps, the attempts of the Polish Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

to prevent further warfare turned futile. Józef Piłsudski, who ruled over the military and to a considerable degree over the weak civilian government, prevented any movement toward peace. By late February, he directed the Polish representatives to engage in pretended negotiations with the Soviets. Piłsudski and his collaborators stressed what they saw as the increasing with time Polish military advantage over the Red Army and their belief that the state of war had created highly favorable conditions for Poland's economic development.

On 4 March 1920, General Władysław Sikorski initiated a new offensive in Polesia

Polesia, Polesie, or Polesye, uk, Полісся (Polissia), pl, Polesie, russian: Полесье (Polesye) is a natural and historical region that starts from the farthest edge of Central Europe and encompasses Eastern Europe, including East ...

; the Polish forces had driven a wedge between Soviet forces to the north (Belarus) and south (Ukraine). The Soviet counter-offensive in Polesia and Volhynia was pushed back.

Polish–Russian peace negotiations in March 1920 produced no results. Piłsudski was not interested in a negotiated solution to the conflict. Preparations for a large-scale resumption of hostilities were being finalized and the newly declared (over the protest of a majority of parliamentary deputies) marshal and his circle expected the planned new offensive to lead to the fulfillment of Piłsudski's federalist ideas.Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

of the negative developments, urging them to prevent the forthcoming Polish aggression. The Polish diplomacy claimed the necessity to counteract the immediate threat of a Soviet assault in Belarus, but the Western opinion, to whom the Soviet arguments seemed reasonable, rejected the Polish narrative. The Soviet forces on the Belarusian front were weak at the time and the Bolsheviks had no plans for an offensive action.

Piłsudski's alliance with Petliura

Having resolved Poland's armed conflicts with the emerging Ukrainian states to Poland's satisfaction, Piłsudski was able to work on a Polish–Ukrainian alliance against Russia.

Having resolved Poland's armed conflicts with the emerging Ukrainian states to Poland's satisfaction, Piłsudski was able to work on a Polish–Ukrainian alliance against Russia.Hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military ...

Symon Petliura, the exiled Ukrainian nationalist leader, and two other members of the Directorate of Ukraine, was signed on 21 April 1920.political asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another entit ...

. His control extended only to a sliver of land near the Polish-controlled areas.Zbruch

The Zbruch ( uk, Збруч, pl, Zbrucz) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.[Збруч< ...]

River. In exchange for renouncing the Ukrainian territorial claims, he was promised independence for Ukraine and Polish military assistance in reinstating his government in Kiev. For Piłsudski, the alliance gave his campaign for the '' Intermarium'' federation an actual starting point and potentially the most important federation partner, satisfied his demands regarding parts of Polish eastern border relevant to the proposed Ukrainian state and laid a foundation for a Polish-dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland.

For Piłsudski, the alliance gave his campaign for the '' Intermarium'' federation an actual starting point and potentially the most important federation partner, satisfied his demands regarding parts of Polish eastern border relevant to the proposed Ukrainian state and laid a foundation for a Polish-dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland.[ According to Richard K. Debo, while Petliura could not contribute real strength to the Polish offensive, for Piłsudski the alliance provided some camouflage for the "naked aggression involved".][ For Petliura, it was the final chance to preserve the Ukrainian statehood and at least a theoretical independence of the Ukrainian heartlands, despite his acceptance of the loss of West Ukrainian lands to Poland.

The British and the French did not recognize the UPR and blocked its admission to the ]League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

in autumn 1920. The treaty with the Ukrainian republic did not generate any international support for Poland. It caused new tensions and conflicts, especially within the Ukrainian movements that aimed for the country's independence.

Regarding the deal they had concluded, both leaders encountered strong opposition in their respective countries. Piłsudski faced stiff opposition from Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

's National Democrats, who opposed Ukrainian independence.Leopold Skulski

Leopold Skulski ; (15 November 1878, Zamość – Brest, 11 June 1940) served as prime minister of Poland for six months from 13 December 1919 until 9 June 1920 in the interim Legislative Sejm during the formation of sovereign Second Polish ...

, Piłsudski emphasized that the railroad booty had been enormous, but he could not divulge further because the appropriations took place in violation of Poland's treaty with Ukraine.

The alliance with Petliura gave Poland 15,000 allied Ukrainian troops at the beginning of the Kiev campaign,

From Kiev Offensive to armistice

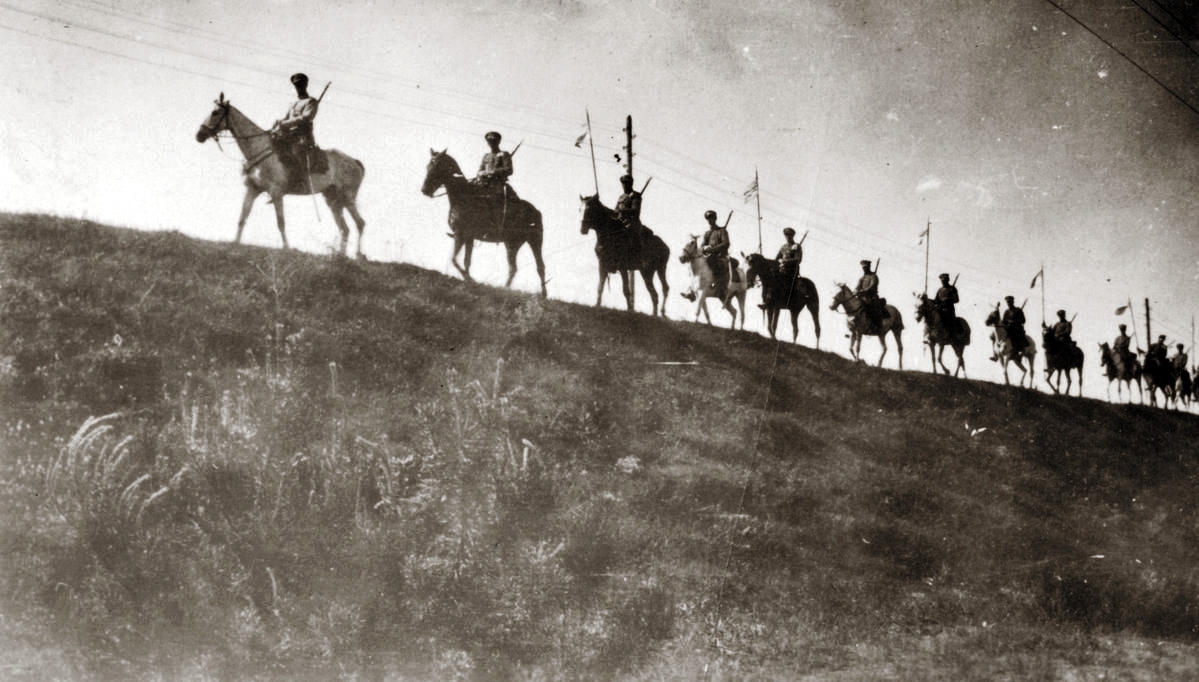

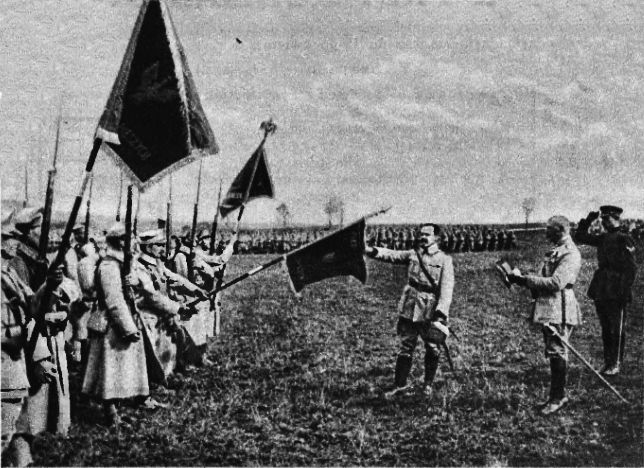

Polish forces

The Polish Army was made up of soldiers who had served in the armies of the partitioning empires (especially professional

The Polish Army was made up of soldiers who had served in the armies of the partitioning empires (especially professional officers

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fr ...

), as well as many new enlistees and volunteers. The soldiers had come from different armies, formations, backgrounds and traditions. While veterans of Piłsudski's Polish Legions and the Polish Military Organisation formed a privileged stratum, integrating the Greater Poland Army and the Polish Army from France into the national force presented many challenges. The unification of the Greater Poland Army led by General Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki

Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki (Iosif Romanovich while in the Russian military; sometimes also Dowbór-Muśnicki; ; 25 October 1867 – 26 October 1937) was a Russian military officer and Polish general, serving with the Imperial Russian and then Pol ...

(a highly regarded force of 120,000 soldiers), and the Polish Army from France led by General Józef Haller, with the main Polish Army under Józef Piłsudski, had been finalized on 19 October 1919 in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

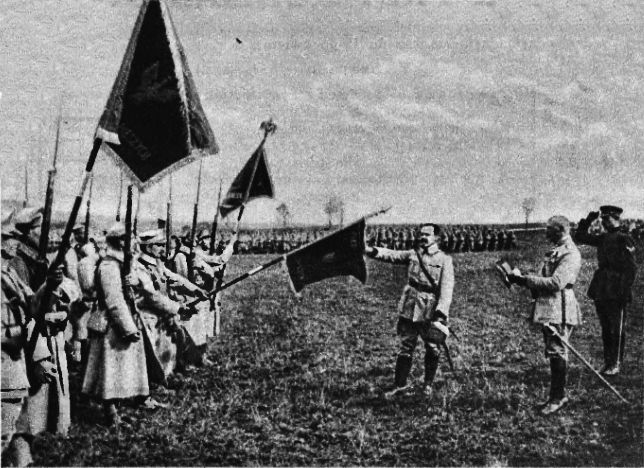

, in a symbolic ceremony.

Within the young Polish state whose continuous existence was uncertain, members of many groups resisted conscription. For example, Polish peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

s and small town dwellers, Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, or Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

from Polish-controlled territories tended to avoid service in Polish armed forces for different reasons. The Polish military was overwhelmingly ethnically Polish and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The intensifying desertion problem in summer 1920 led to the introduction of death penalty for desertion in August. The summary military trials and the executions often took place on the same day.

Female soldiers functioned as members of the Voluntary Legion of Women

Voluntary Legion of Women ( pl, Ochotnicza Legia Kobiet (OLK)) was a voluntary Polish paramilitary organization, created by women in Lviv in late 1918. At that time possession of the city was contested by the Poles and Ukrainians, and women decided ...

; they were normally assigned auxiliary duties. A system of military training for officers and soldiers was established with significant help from the French Military Mission to Poland

The French Military Mission to Poland was an effort by France to aid the nascent Second Polish Republic after it achieved its independence in November 1918, at the end of the First World War. The aim was to provide aid during the Polish-Soviet Wa ...

.

The Polish Air Force had about two thousand planes, mostly old. 45% of them had been captured from the enemy. Only two hundred could be airborne at any given time. They were used for various purposes including combat, but mostly for reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

. 150 French pilots and navigators flew as part of the French Mission.

According to Norman Davies, estimating the strength of the opposing sides is difficult and even generals often had incomplete reports of their own forces.

The Polish forces grew from approximately 100,000 by the end of 1918 to over 500,000 in early 1920 and 800,000 in the spring of that year. Before the Battle of Warsaw, the army reached the total strength of about one million soldiers, including 100,000 volunteers.

The Polish armed forces were aided by military members of Western missions, especially the French Military Mission. Poland was supported, in addition to the allied Ukrainian forces (over twenty thousand soldiers), by Russian and Belarusian units and volunteers of many nationalities. Twenty American pilots served in the Kościuszko Squadron. Their contributions in spring and summer 1920 on the Ukrainian front were considered to be of critical importance.

Russian anti-Bolshevik units fought on the Polish side. About one thousand

The Polish armed forces were aided by military members of Western missions, especially the French Military Mission. Poland was supported, in addition to the allied Ukrainian forces (over twenty thousand soldiers), by Russian and Belarusian units and volunteers of many nationalities. Twenty American pilots served in the Kościuszko Squadron. Their contributions in spring and summer 1920 on the Ukrainian front were considered to be of critical importance.

Russian anti-Bolshevik units fought on the Polish side. About one thousand White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

soldiers fought in summer 1919. The largest Russian formation was sponsored by the Russian Political Committee represented by Boris Savinkov

Boris Viktorovich Savinkov (Russian: Бори́с Ви́кторович Са́винков; 31 January 1879 – 7 May 1925) was a Russian writer and revolutionary. As one of the leaders of the Fighting Organisation, the paramilitary wing ...

and commanded by General Boris Permikin. The "3rd Russian Army" reached over ten thousand battle-ready soldiers and in early October 1920 was dispatched to the front to fight on the Polish side; they did not engage in combat because of the armistice that took effect at that time. Six thousand soldiers fought valiantly on the Polish side in the " Cossack" Russian units from 31 May 1920. Various smaller Belarusian formations fought in 1919 and 1920. However, the Russian, Cossack and Belarusian military organizations had their own political agendas and their participation has been marginalized or omitted in the Polish war narrative.

Soviet losses and the spontaneous enrollment of Polish volunteers allowed rough numerical parity between the two armies;

Red Army

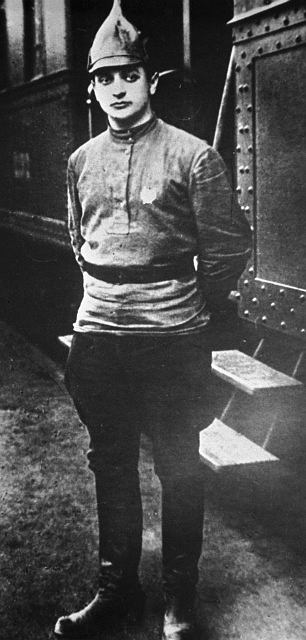

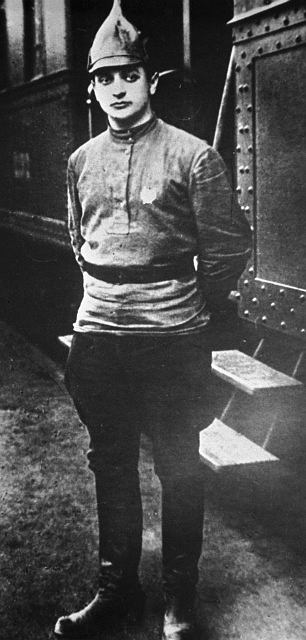

In early 1918, Lenin and

In early 1918, Lenin and Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

embarked on the rebuilding of the Russian armed forces. The new Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

was established by the Council of People's Commissars