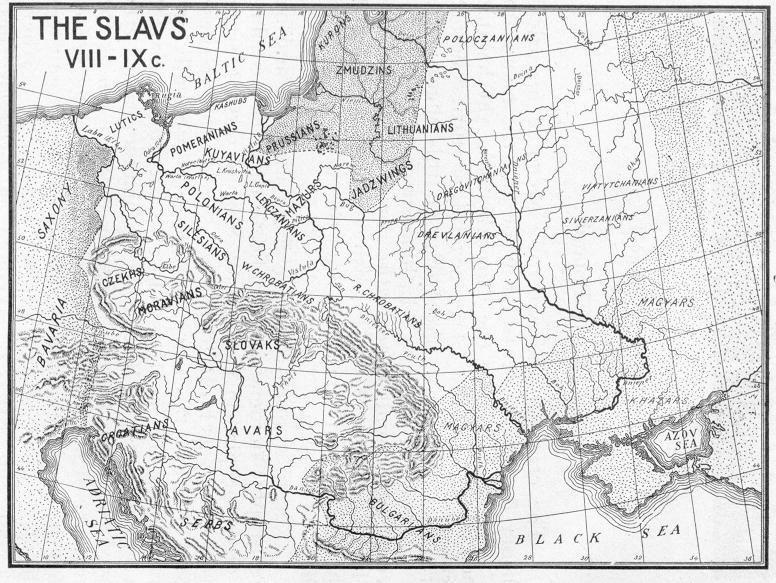

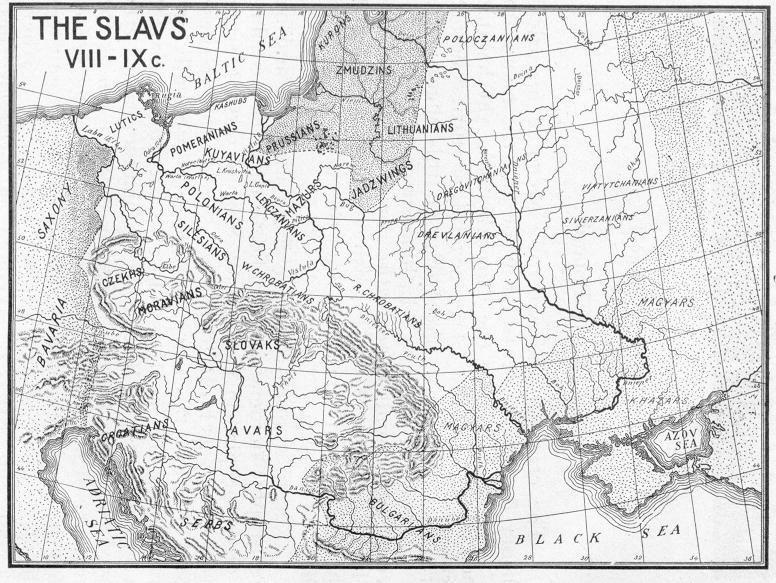

The most important phenomenon that took place within the lands of Poland in the Early Middle Ages, as well as other parts of

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

was the arrival and permanent settlement of the

West Slavic or

Lechitic peoples.

The Slavic

migrations to the area of contemporary Poland started in the second half of the 5th century AD, about a half century after these territories were vacated by

Germanic tribes fleeing from the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

.

The first waves of the incoming Slavs settled the vicinity of the upper

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

River and elsewhere in the lands of present southeastern

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and southern

Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

. Coming from the east, from the upper and middle regions of the

Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

, the immigrants would have had come primarily from the western branch of the early Slavs known as

Sclaveni

The ' (in Latin) or ' (various forms in Greek, see below) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became the progenitors of modern South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byz ...

, and since their arrival are classified as

West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic lan ...

and

Lechites

Lechites (, german: Lechiten), also known as the Lechitic tribes (, german: Lechitische Stämme), is a name given to certain West Slavic tribes who inhabited modern-day Poland and eastern Germany, and were speakers of the Lechitic languages. Dist ...

, who are the closest ancestors of

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

.

From there the new population dispersed north and west over the course of the 6th century. The Slavs lived from cultivation of crops and were generally farmers, but also engaged in

hunting and gathering

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

. The migrations took place when the destabilizing invasions of Eastern and Central Europe by waves of people and armies from the east, such as the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

,

Avars and

Magyars, were occurring. This westward movement of Slavic people was facilitated in part by the previous

emigration of Germanic peoples toward the safer areas of Western and Southern Europe. The immigrating Slavs formed various small tribal organizations beginning in the 8th century, some of which coalesced later into larger, state-like ones.

Beginning in the 7th century, these tribal units built many fortified structures with earth and wood walls and embankments, called

gords. Some of them were developed and inhabited, others had a very large empty area inside the walls.

By the 9th century, the West Slavs had settled the

Baltic coast

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10 ...

in

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, which subsequently developed into a commercial and military power.

Along the coastline, remnants of

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

n settlements and

emporia were to be found. The most important of them was probably the trade settlement and seaport of

Truso

Truso was a Viking Age port of trade (emporium) set up by the Scandinavians at the banks of the Nogat delta branch of the Vistula River, close to a bay (the modern Drużno lake), where it emptied into the shallow and brackish Vistula Lagoon. This ...

,

located in

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

. Prussia itself was relatively unaffected by Slavic migration and remained inhabited by

Baltic Old Prussians

Old Prussians, Baltic Prussians or simply Prussians ( Old Prussian: ''prūsai''; german: Pruzzen or ''Prußen''; la, Pruteni; lv, prūši; lt, prūsai; pl, Prusowie; csb, Prësowié) were an indigenous tribe among the Baltic peoples that ...

. During the same time, the tribe of the

Vistulans

The Vistulans, or Vistulanians ( pl, Wiślanie), were an early medieval Lechitic tribe inhabiting the western part of modern Lesser Poland."The main tribe inhabiting the reaches of the Upper Vistula and its tributaries was the Vislane (Wislanie) ...

(''Wiślanie''), based in

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

and the surrounding region, controlled a large area in the south, which they developed and fortified with many strongholds.

During the 10th century, the Lechitic

Western Polans (''Polanie'', lit. "people of the open fields") turned out to be of decisive historic importance. Initially based in the central Polish lowlands around

Giecz

Giecz is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Dominowo, within Środa Wielkopolska County, Greater Poland Voivodeship, in west-central Poland. It lies approximately north of Dominowo, north-east of Środa Wielkopolska, and east ...

,

Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

and

Gniezno

Gniezno (; german: Gnesen; la, Gnesna) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. One of the Piast dynasty's chief cities, ...

, the Polans went through a period of accelerated building of fortified settlements and territorial expansion beginning in the first half of the 10th century. Under duke

Mieszko I of the

Piast dynasty, the expanded Polan territory was

converted to Christianity in 966, which is generally regarded the birth of the Polish state. The contemporary names of the realm, "Mieszko's state" or "Gniezno state", were dropped soon afterwards in favour of "Poland", a rendering of the Polans' tribal name. The Piast dynasty would continue to

rule Poland until the late 14th century.

Origin of the Slavic peoples

Slavic beginnings of Poland

The origins of the

Slavic peoples, who arrived on Polish lands at the outset of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

as representatives of the

Prague culture

The Prague-Korchak culture was an archaeological culture attributed to the Early Slavs. The other contemporary main Early Slavic culture was the Prague-Penkovka culture situated further south, with which it makes up the "Prague-type pottery" grou ...

, go back to the

Kiev culture, which formed beginning early in the 3rd century AD and is genetically derived from the Post-Zarubintsy

cultural horizon (Rakhny–Ljutez–Pochep material culture sphere)

and itself was one of the later post-

Zarubintsy culture

The Zarubintsy or Zarubinets culture was a culture that, from the 3rd century BC until the 1st century AD, flourished in the area north of the Black Sea along the upper and middle Dnieper and Pripyat Rivers, stretching west towards the Southern ...

groups.

Such an ethnogenetic relationship is apparent between the large Kiev culture population and the early (6th–7th centuries) Slavic settlements in the

Oder and

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

basins, but lacking between these Slavic settlements and the

older local cultures within the same region, that ceased to exist beginning in the 400–450 AD period.

Zarubintsy culture

The

Zarubintsy culture

The Zarubintsy or Zarubinets culture was a culture that, from the 3rd century BC until the 1st century AD, flourished in the area north of the Black Sea along the upper and middle Dnieper and Pripyat Rivers, stretching west towards the Southern ...

circle, in existence roughly from 200 BC to 150 AD, extended along the middle and upper

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

and its tributary the

Pripyat River

The Pripyat or Prypiat ( , uk, Прип'ять, ; be, Прыпяць, translit=Prypiać}, ; pl, Prypeć, ; russian: Припять, ) is a river in Eastern Europe, approximately long. It flows east through Ukraine, Belarus, and Ukraine ag ...

, but also left traces of settlements in parts of

Polesie and the upper

Bug River

uk, Західний Буг be, Захо́дні Буг

, name_etymology =

, image = Wyszkow_Bug.jpg

, image_size = 250

, image_caption = Bug River in the vicinity of Wyszków, Poland

, map = Vi ...

basin. The main distinguished local groups were the Polesie group, the Middle Dnieper group and the Upper Dnieper group. The Zarubintsy culture developed from the

Milograd culture

The Milograd culture (also spelled Mylohrad, also known as Pidhirtsi culture on Ukrainian territory) is an archaeological culture, lasting from about the 7th century BC to the 1st century AD. Geographically, it corresponds to present day souther ...

in the northern part of its range and from the local

Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

populations in the more southern part. The Polesie group's origin was also influenced by the

Pomeranian and

Jastorf culture

The Jastorf culture was an Iron Age material culture in what is now northern Germany and southern Scandinavia spanning the 6th to 1st centuries BC, forming part of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and associating with Germanic peoples. The culture evo ...

s. The Zarubintsy culture and its beginnings were moderately affected by

La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defi ...

and the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

area (trade with the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

cities provided imported items) centers of civilization in the earlier stages, but not much by

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

influence later on, and accordingly its economic development was lagging behind that of other early Roman period cultures. Cremation of bodies was practiced, with the human remains and burial gifts including metal decorations, small in number and limited in variety, placed in pits.

Kiev culture

Originating from the Post-Zarubintsy cultures and often considered the oldest Slavic culture, the

Kiev culture functioned during the later Roman periods (end of 2nd through mid-5th century)

north of the vast

Chernyakhov culture

The Chernyakhov culture, Cherniakhiv culture or Sântana de Mureș—Chernyakhov culture was an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Rom ...

territories, within the basins of the upper and middle Dnieper,

Desna and

Seym rivers. The

archeological cultural features of the Kiev sites show this culture to be identical or highly compatible (representing the same cultural model) with that of the 6th-century Slavic societies, including the settlements on the lands of today's Poland.

The Kiev culture is known mostly from settlement sites; the burial sites, involving pit graves, are few and poorly equipped. Not many metal objects have been found, despite the known native production of iron and processing of other metals, including

enamel coating technology. Clay vessels were made without the

potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, a ...

. The Kiev culture represented an intermediate level of development, between that of the cultures of the Central European Barbaricum, and the forest zone societies of the eastern part of the continent. The Kiev culture consisted of four local formations: The Middle Dnieper group, the Desna group, the Upper Dnieper group and the Dnieper-Don group. The general model of the Kiev culture is like that of the early Slavic cultures that were to follow and must have originated mainly from the Kiev groups, but evolved probably over a larger territory, stretching west to the base of the

Eastern Carpathian Mountains

Divisions of the Carpathians are a categorization of the Carpathian mountains system.

Below is a detailed overview of the major subdivisions and ranges of the Carpathian Mountains. The Carpathians are a "subsystem" of a bigger Alps-Himalaya ...

, and from a broader Post-Zarubintsy foundation. The Kiev culture and related groups expanded considerably after 375 AD, when the

Ostrogothic

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

state, and more broadly speaking the Chernyakhov culture, were destroyed by the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

. This process was facilitated further and gained pace, involving at that time the Kiev's descendant cultures, when the Hun confederation itself broke down in the mid-5th century.

Written sources

The eastern cradle of the Slavs is also directly confirmed by a written source. The anonymous author known as the

Cosmographer of Ravenna

The ''Ravenna Cosmography'' ( la, Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia, "The Cosmography of the Unknown Ravennese") is a list of place-names covering the world from India to Ireland, compiled by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna around 700 AD. Text ...

(c. 700) names

Scythia

Scythia (Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

Hi ...

, a geographic region encompassing vast areas of eastern Europe,

as the place "where the generations of the Sclaveni had their beginnings".

Scythia, "stretching far and spreading wide" in the eastern and southern directions, had at the west end, as seen at the time of

Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') a ...

' writing (first half to mid-6th century) or earlier, "the Germans and the river Vistula".

Jordanes places the Slavs in Scythia as well.

Alternative point of view

According to an alternative theory, popular in the earlier 20th century and still represented today, the medieval cultures in the area of modern Poland are not a result of massive immigration, but emerged from a cultural transition of

earlier indigenous populations, who then would need to be regarded as early Slavs. This view has mostly been discarded, primarily due to a period of archaeological discontinuity, during which settlements were absent or rare, and because of cultural incompatibility of the late ancient and early medieval sites.

A 2011 article on the early Western Slavs states that the transitional period (of relative depopulation) is difficult to evaluate archeologically. Some believe that the Late Antique "Germanic" populations (in Poland late Przeworsk culture and others) abandoned East Central Europe and were replaced by the Slavs coming from the east, others see the "Germanic" groups as staying and becoming, or already being, Slavs. Current archeology, says the author, "is unable to give a satisfying answer and probably both aspects played a role". In terms of their origin, territorial and linguistic, "Germanic" groups should not be played off against "Slavs", as our current understanding of the terms may have limited relevance to the complex realities of the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages. Local languages in the region cannot be identified by archeological studies, and genetic evaluation of cremation burial remains has not been possible.

Slavic differentiation and expansion; Prague culture

Kolochin culture, Penkovka culture and Prague–Korchak culture

The final process of the differentiation of the cultures recognized as early Slavic, the Kolochin culture] (over the territory of the Kiev culture), the

Antes (people), Penkovka culture and the

Prague-Korchak culture

The Prague-Korchak culture was an archaeological culture attributed to the Early Slavs. The other contemporary main Early Slavic culture was the Prague-Penkovka culture situated further south, with which it makes up the "Prague-type pottery" grou ...

, took place during the end of the 4th and in the 5th century CE. Beyond the Post-Zarubintsy horizon, the expanding early Slavs took over much of the territories of the

Chernyakhov culture

The Chernyakhov culture, Cherniakhiv culture or Sântana de Mureș—Chernyakhov culture was an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Rom ...

and the

Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

n

Carpathian Tumuli culture. As not all of the previous inhabitants from those cultures had left the area, they probably contributed some elements to the Slavic cultures.

The Prague culture developed over the western part of the Slavic expansion within the basins of the middle

Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

,

Pripyat River

The Pripyat or Prypiat ( , uk, Прип'ять, ; be, Прыпяць, translit=Prypiać}, ; pl, Prypeć, ; russian: Припять, ) is a river in Eastern Europe, approximately long. It flows east through Ukraine, Belarus, and Ukraine ag ...

and upper

Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

up to the

Carpathian Mountains and in southeastern Poland, i.e., the upper and middle

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

basin. This culture was responsible for most of the growth in 6th and 7th centuries, by which time it also encompassed the middle

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

and middle

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

basins.

The Prague culture very likely corresponds to the Sclaveni referred to by

Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') a ...

, whose area he described as extending west to the Vistula sources. The Penkovka culture people inhabited the southeastern part, from

Seversky Donets

The Seversky Donets () or Siverskyi Donets (), usually simply called the Donets, is a river on the south of the East European Plain. It originates in the Central Russian Upland, north of Belgorod, flows south-east through Ukraine (Kharkiv, Done ...

to the lower

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

(including the region where the Antes would be), and the Kolochin culture was located north of the more eastern area of the Penkovka culture (the upper

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

and

Desna basins). The Korchak type designates the eastern part of the Prague-Korchak culture, which was somewhat less directly dependent on the mother Kiev culture than its two sister cultures because of its western expansion. The early 6th-century Slavic settlements covered an area three times the size of the Kiev culture region some hundred years earlier.

Early settlements, economy and burials in Poland

In Poland, the earliest archeological sites considered Slavic include a limited number of 6th-century settlements and a few isolated burial sites. The material obtained there consists mostly of simple, manually formed ceramics, typical of the entire early Slavic area. It is on the basis of the different varieties of these basic clay pots and infrequent decorations that the three cultures are distinguished. The largest of the earliest Slavic (Prague culture) settlement sites in Poland that have been subjected to systematic research is located in Bachórz,

Rzeszów

Rzeszów ( , ; la, Resovia; yi, ריישא ''Raisha'')) is the largest city in southeastern Poland. It is located on both sides of the Wisłok River in the heartland of the Sandomierz Basin. Rzeszów has been the capital of the Subcarpathian ...

County, and dates to the second half of 5th through 7th centuries. It consisted of 12 nearly square, partially dug-out houses, each covering the area of 6.2 to 19.8 (14.0 on the average) square meters. A stone furnace was usually placed in a corner, which is typical for Slavic homesteads of that period, but clay ovens and centrally located hearths are also found.

45 newer dwellings of a different type from the 7th/8th to 9th/10th centuries have also been discovered in the vicinity.

Poorly developed handicraft and limited resources for metal working are characteristic of the communities of all early Slavic cultures. There were no major iron production centers, but metal founding techniques were known; among the metal objects occasionally found are iron knives and hooks, as well as bronze decorative items (as can be found in 7th-century finds in Haćki,

Bielsk Podlaski County, a site of one of the earliest fortified settlements). The inventories of the typical small open settlements also normally include various utensils made of stone, horn and clay (including weights used for weaving). The settlements were arranged as clusters of cabins along river or stream valleys, but above their flood levels, they were usually irregular and typically faced south. The wooden frame or pillar-supported square houses covered with a straw roof had each sides of 2.5 to 4.5 meters in length. Fertile lowlands were sought, but also forested areas with diversified plant and animal environment to provide additional sustenance. The settlements were self-sufficient; the early Slavs functioned without significant long-distance trade. Potter's wheels were used from the turn of the 7th century on. Some villages larger than a few homes have been discovered in the

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

-Nowa Huta region from the 6th to 9th century, for example a complex of 11 settlements on the left bank of the Vistula in the direction of Igołomia. The original furnishings of Slavic huts are difficult to determine, because equipment was often made of perishable materials such as wood, leather or fabrics. Free- standing clay dome stoves for bread baking have been found on some locations. Another large 6th– to 9th-century settlement complex existed in the vicinity of

Głogów

Głogów (; german: Glogau, links=no, rarely , cs, Hlohov, szl, Głogōw) is a city in western Poland. It is the county seat of Głogów County, in Lower Silesian Voivodeship (since 1999), and was previously in Legnica Voivodeship (1975–199 ...

in

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

.

[''Słowianie nad Bzurą'' by Marek Dulinicz and Felix Biermann, '' Archeologia Żywa'', issue 1 (16) 2001]

The Slavic people cremated their dead, typical for the inhabitants of their region for centuries. The burials were usually single, the graves grouped in small cemeteries, with the ashes placed in simple urns more often than in ground indentations. The number of burial sites found is small in relation to the known settlement density. The food production economy was based on millet and wheat cultivation, hunting, fishing, gathering and cattle breeding (swine, sheep and goats bred to a lesser extent).

Geographic expansion in Poland and Central Europe

The earliest Slavic settlers from the east reached southeastern Poland in the second half of the 5th century, specifically the

San River

The San ( pl, San; uk, Сян ''Sian''; german: Saan) is a river in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine, a tributary of the river Vistula, with a length of (it is the 6th-longest Polish river) and a basin area of 16,877 km2 (14,42 ...

basin, then the upper

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

regions, including the

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

area and

Nowy Sącz Valley. Single early sites are also known around

Sandomierz

Sandomierz (pronounced: ; la, Sandomiria) is a historic town in south-eastern Poland with 23,863 inhabitants (as of 2017), situated on the Vistula River in the Sandomierz Basin. It has been part of Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (Holy Cross Prov ...

and

Lublin in

Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

and

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

. Somewhat younger settlement concentrations were discovered in

Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

. In the 6th century, the above areas were settled. At the end of this century, or in the early 7th century, the Slavic newcomers reached

Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, Weste ...

. According to the

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

historian

Theophylact Simocatta

Theophylact Simocatta (Byzantine Greek: Θεοφύλακτος Σιμοκάτ(τ)ης ''Theophýlaktos Simokát(t)ēs''; la, Theophylactus Simocatta) was an early seventh-century Byzantine historiographer, arguably ranking as the last historian o ...

, the Slavs captured in

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

in 592 named the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

coastal area as the place from which they originated.

As of that time and in the following decades, Western Pomerania, plus some of

Greater Poland, Lower Silesia and some areas west of the middle and lower

Oder River made up the Sukow-Dziedzice culture group. Its origin is the subject of debate among archeologists. First settlements appear in the early 6th century and cannot be directly derived from any other Slavic archeological culture. They reveal certain similarities to the artifacts of the Dobrodzień group of the

Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first Artifact (arch ...

. According to scholars such as Siedow, Kurnatowska and Brzostowicz, it might be a direct continuation of the Przeworsk tradition. According to allochthonists, it represents a variant of the Prague culture and is considered its younger stage. The Sukow-Dziedzice group shows significant idiosyncrasies, such as no graves and (typical for the rest of the Slavic world) rectangular dwellings set partially below the ground level were found within its span.

This particular pattern of expansion into the lands of Poland and then Germany was a part of the great Slavic migration during the 5th-7th centuries from originating lands in the east to various countries of Central and Southeastern Europe. Another 6th-century route, more southern, took the Prague culture of the Slavs through

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

,

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

and

Bohemia. The Slavs also reached the eastern

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

and populated the

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

and the

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

basins, from where they moved south to occupy the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

as far as

Peloponnese.

Ancient and early Medieval written accounts of the Slavs

Besides the Baltic

Veneti (see

Poland in Antiquity article), ancient and medieval authors speak of the East European, or Slavic Venethi. It can be inferred from

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

' description in ''

Germania'' that his "Venethi" possibly lived around the middle

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

basin, which in his times would correspond to the Proto-Slavic

Zarubintsy cultural sphere. Jordanes, to whom the Venethi meant Slavs, wrote of past fighting between the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

and the Venethi that took place during the third quarter of the 4th century in today's

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. At that time, the Venethi therefore would have been people of the

Kiev culture. The Venethi, Jordanes reported, "now rage in war far and wide, in punishment for our sins",

and were at that time made obedient to the Gothic king

Hermanaric. Jordanes' 6th-century description of the "populous race of the Venethi"

includes indications of their dwelling places in the regions near the northern ridge of the Carpathian Mountains and stretching from there "almost endlessly" east, while in the western direction reaching the sources of the Vistula. More specifically, he designates the area between the Vistula and the lower

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

as the country of the

Sclaveni

The ' (in Latin) or ' (various forms in Greek, see below) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became the progenitors of modern South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byz ...

. "They have swamps and forests for their cities" (''hi paludes silvasque pro civitatibus habent''),

he added sarcastically. The "bravest of these peoples",

the

Antes, settled the lands between the

Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

and the

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

rivers. The Venethi were the third Slavic branch of an unspecified location (most likely of the Kolochin culture), as well as the overall designation for the totality of the Slavic peoples, who "though off-shoots from one stock, have now three names".

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

in ''De Bello Gothico'' located the "countless Antes tribes" even further east, beyond the Dnieper.

Together with the Sclaveni, they spoke the same language, of an "unheard of barbarity".

According to Jordanes, the

Heruli

The Heruli (or Herules) were an early Germanic people. Possibly originating in Scandinavia, the Heruli are first mentioned by Roman authors as one of several " Scythian" groups raiding Roman provinces in the Balkans and the Aegean Sea, attacking ...

nation traveled in 512 across all of the Sclaveni peoples territories, and then west of there through a large expanse of unpopulated lands, as the Slavs were about to settle the western and northern parts of Poland in the decades to follow.

All of the above is in good accordance with the findings of today's archeology.

Byzantine writers held the Slavs in low regard for the simple life they led and also for their supposedly limited combat abilities, but in fact they were already a threat to the Danubian boundaries of the Empire in the early 6th century, where they waged plundering expeditions.

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

, the anonymous author of ''

Strategicon'', and

Theophylact Simocatta

Theophylact Simocatta (Byzantine Greek: Θεοφύλακτος Σιμοκάτ(τ)ης ''Theophýlaktos Simokát(t)ēs''; la, Theophylactus Simocatta) was an early seventh-century Byzantine historiographer, arguably ranking as the last historian o ...

wrote at some length on how to deal with the Slavs militarily, which suggests that they had become a formidable adversary.

John of Ephesus

John of Ephesus (or of Asia) ( Greek: Ίωάννης ό Έφέσιος, c. 507 – c. 588) was a leader of the early Syriac Orthodox Church in the sixth century and one of the earliest and the most important historians to write in Syriac. John of ...

actually goes as far as saying in the last quarter of the 6th century that the Slavs had learned to conduct war better than the Byzantine army. The

Balkan Peninsula was indeed soon overrun by the Slavic invaders during the first half of the 7th century under Emperor

Heraclius.

The above-mentioned authors provide various details on the character, living conditions, social structure and economic activities of the early Slavic people, some of which are confirmed by the archeological discoveries in Poland, since the Slavic communities were quite similar all over their range.

Their uniform

Old Slavic language remained in use until the 9th to 12th centuries, depending on the region. The Greek missionaries

Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

from

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, where "everybody fluently spoke Slavic", were expected to be able to communicate in distant

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

without any difficulty when sent there in 863 by the Byzantine ruler.

Invasions of the Avars in Europe and their presence in Poland

In the 6th century, the

Turkic-speaking nomadic

Avars moved into the middle Danube area. Twice (in 562 and 566–567), the Avars undertook military expeditions against the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, and their routes went through the Polish lands. The Avar envoys bribed Slavic chiefs from the lands they did not control, including

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, to secure their participation in Avar raids, but other than that, the exact nature of their relations with the Slavs in Poland is not known. The Avars had some presence or contacts in Poland also in the 7th and 8th centuries, when they left artifacts in the Kraków-Nowa Huta region and elsewhere, including a bronze belt decoration found in the

Krakus Mound

Krakus Mound ( pl, kopiec Krakusa), also called the Krak Mound, is a tumulus located in the Podgórze district of Kraków, Poland; thought to be the resting place of Kraków's mythical founder, the legendary King Krakus. It is located on Lasota ...

. This last item, from the turn of the 8th century, is used to date the mound itself.

Tribal differentiation

8th-century settlements

With the major population shifts of the Slavic migrations completed, the 8th century brought a measure of stability to the Slavic people settled in Poland. About one million people actively utilized no more than 20–25% of the land; the rest was mainly forest. Normal settlements, with the exception of a few fortifications and cult venues, were limited to lowland areas below 350 meters above the sea level. Most villages built without artificial defensive structures were located within valley areas of natural bodies of water. The Slavs were very familiar with the water environment and used it as natural defense.

The living and economic activity structures were either distributed randomly or arranged in rows or around a central empty lot. The larger settlements could have had over a dozen homesteads and be occupied by 50 to 80 residents, but more typically there were just several homes with no more than 30 inhabitants. From the 7th century on, the previously common semi-subterranean dwellings were being replaced by buildings wholly above the surface, but still consisted of just one room. Pits were dug for storage and other uses. As the Germanic people before them, the Slavs left vacant regions between developed areas for separation from strangers and to avoid conflicts, especially along the limits of their tribal territories.

Gord construction

The

Polish tribes

"Polish tribes" is a term used sometimes to describe the tribes of West Slavic Lechites that lived from around the mid-6th century in the territories that became Polish with the creation of the Polish state by the Piast dynasty. The territory ...

did build more imposing structures than the simple dwellings in their small communities: fortified settlements and other reinforced enclosures of the

gord (Polish "gród") type. These were established on naturally suitable, defense-enhancing sites beginning in the late 6th or 7th century. Szeligi near

Płock

Płock (pronounced ) is a city in central Poland, on the Vistula river, in the Masovian Voivodeship. According to the data provided by GUS on 31 December 2021, there were 116,962 inhabitants in the city. Its full ceremonial name, according to th ...

and Haćki are the early examples. A large-scale building effort took place in the 8th century. The gords were differently designed and of various sizes, from small to impressively massive. Ditches, walls, palisades and embankments were used to strengthen the perimeter, which often involved a complicated earthwork besides wood and stone construction. Gords of the tribal period were irregularly distributed across the country (there were fewer larger ones in

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

, but more smaller ones in central and northern Poland),

and could cover an area from 0.1 to 25

hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100- metre sides (1 hm2), or 10,000 m2, and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. An acre is ...

s. They could have a simple or multi-segment architecture and be protected by fortifications of different types. Some were permanently occupied by a substantial number of people or by a chief and his cohort of armed men, while others were utilized as refuges to protect the local population in case of external danger. Beginning in the 9th century, the gords became the nuclei of future urban developments, attracting tradesmen of all kinds, especially in strategic locations. Gords erected in the 8th century have been researched extensively, for example the ones in

Międzyświeć (

Cieszyn County, Gołęszyce tribe) and Naszacowice (

Nowy Sącz County). The last one was destroyed and rebuilt four times, with the final reconstruction completed after 989.

A monumental and technically complex border protection area gord of over 3 hectares in size was built around 770–780 in

Trzcinica near

Jasło

Jasło is a county town in south-eastern Poland with 36,641 inhabitants, as of 31 December 2012. It is situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (since 1999), and it was previously part of Krosno Voivodeship (1975–1998). It is located in Lesse ...

on the site of an old

Bronze Age era stronghold, probably the seat of a local ruler and his garrison. Thousands of relics were found there, including a silver treasure of 600 pieces. The gord was set afire several times and ultimately destroyed during the first half of the 11th century.

This larger scale building activity, from the mid-8th century on, was a manifestation of the emergence of tribal organisms, a new civilizational quality that represented rather efficient proto-political organizations and social structures on a new level. They were based on these fortifications, defensive objects, of which the mid-8th century and later

Vistulan gords in

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

are a good example. The threat coming from the

Avar state in

Pannonia could have had provided the original motivation for the construction projects.

Society organized into larger tribal units

From the 8th century on, the Slavs in Poland increasingly organized themselves in larger structures known as "great tribes," either through voluntary or forced association. The population was primarily involved in agricultural pursuits. Fields were cultivated as well as gardens within settlements. Plowing was done using oxen and wooden plows reinforced with iron. Forest burning was used to increase the arable area, but also to provide fertilizer, as the ashes lasted in that capacity for several seasons. Rotation of crops was practiced as well as the winter/spring crop system. After several seasons of exploitation, the land was being left idle to regain fertility. Wheat, millet and rye were most important crops; other cultivated plant species included oat, barley, pea, broad bean, lentil, flax and hemp, as well as apple, pear, plum, peach and cherry trees in fruit orchards. Beginning in the 8th century, swine gradually became economically more important than cattle; sheep, goats, horses, dogs, cats, chickens, geese and ducks were also kept. The agricultural practices of the Slavs are known from archeological research, which documents progressive increases over time in arable area and resulting deforestation, and from written reports provided by

Ibrahim ibn Yaqub

Ibrahim ibn Yaqub ( ar, إبراهيم بن يعقوب ''Ibrâhîm ibn Ya'qûb al-Ṭarṭûshi'' or ''al-Ṭurṭûshî''; he, אברהם בן יעקב, ''Avraham ben Yaʿakov''; 961–62) was a tenth-century Hispano-Arabic, Sephardi Jewish t ...

, a 10th-century

Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish traveler. Ibrahim described also other features of Slavic life, for example the use of steam baths. The existence of bath structures has been confirmed by archeology. An anonymous

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

writer from the turn of the 10th century mentions that the Slavic people made an alcoholic beverage out of honey and their celebrations were accompanied by music played on the lute, tambourines and wind instruments.

Gathering, hunting and fishing were still essential as sources of food and materials such as hide or fur. The forest was also exploited as a source of building materials such as wood. In addition, wild forest bees were kept there, and the forest could be used as a place of refuge. Until the 9th century, the population was separated from the main centers of civilization and self-sufficient with primitive, local community and household-based manufacturing. Specialized craftsmen existed only in the fields of iron extraction from ore and processing, and pottery; the few luxury items used were imports. From the 7th century on, modestly decorated ceramics were made with the

potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, a ...

. 7th– to 9th-century collections of objects have been found in Bonikowo and Bruszczewo,

Kościan

Kościan (german: Kosten) is a town on the Obra canal in west-central Poland, with a population of 23 952 inhabitants as of June 2014. Situated in the Greater Poland Voivodeship (since 1999), previously in Leszno Voivodeship (1975–1998), it i ...

County (iron spurs, knives, clay containers with some ornamentation) and in the Kraków-Nowa Huta region (weapons and utensils in Pleszów and Mogiła), among other places. Slavic warriors were traditionally armed with spears, bows and wooden shields. Axes were used later, and still swords of the types popular throughout 7th– to 9th-century Europe were also used. Independent of distant powers, the Slavic tribes in Poland lived a relatively undisturbed life, but at the cost of some backwardness in civilization.

A qualitative change took place in the 9th century, when the Polish lands were crossed again by long-distance trade routes.

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

become a part of the Baltic trade zone, while

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

participated in trade centered in the Danubian countries. In the Upper Vistula basin, Oriental silver jewelry and Arab coins, often cut into pieces, "grzywna" iron coin equivalents (of the type used in

Great Moravia

Great Moravia ( la, Regnum Marahensium; el, Μεγάλη Μοραβία, ''Meghálī Moravía''; cz, Velká Morava ; sk, Veľká Morava ; pl, Wielkie Morawy), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to ...

) and even linen cloths served as currency.

The basic social unit was the nuclear family, consisting of parents and their children, which had to fit in a dwelling area of several to 25 square meters. The "big family," a patriarchal, multi-generational group of related families with the meaning of a kin or clan, was of declining importance during this period. A larger group was needed in the past (5th–7th centuries) for forest clearing and burning undertakings, when farming communities had to shift from location to location; in the 8th-century phase of agriculture, a family was sufficient to take care of their arable land. A concept of agricultural land ownership was gradually developing, at this point a family, not individual prerogative. Several or more clan territories were grouped into a neighborhood association, or "opole", which established a rudimentary self-government. Such a community was the owner of forested land, pastures, bodies of water and within it took place the first organization around common projects and the related development of political power. A big and resourceful opole could become, by extending its possessions, a proto-state entity vaguely referred to as a tribe. The tribe was the top level of this structure. It would contain several opoles and control a region of up to about 1500 square kilometers, where internal relationships were arbitrated and external defense organized.

A general assembly of all tribesmen took care of the most pressing of issues.

Thietmar of Merseburg

Thietmar (also Dietmar or Dithmar; 25 July 9751 December 1018), Prince-Bishop of Merseburg from 1009 until his death, was an important chronicler recording the reigns of German kings and Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (Saxon) dynasty. Two ...

wrote in the early 11th century of the

Veleti

The Veleti, also known as Wilzi, Wielzians, and Wiltzes, were a group of medieval Lechitic tribes within the territory of Hither Pomerania, related to Polabian Slavs. They had formed together the Confederation of the Veleti, a loose monarchic c ...

, a tribe of

Polabian Slavs

Polabian Slavs ( dsb, Połobske słowjany, pl, Słowianie połabscy, cz, Polabští slované) is a collective term applied to a number of Lechitic ( West Slavic) tribes who lived scattered along the Elbe river in what is today eastern Germ ...

, with a report that their assembly kept deliberating till everybody agreed, but this "war democracy" was gradually being replaced by a government system in which the tribal elders and rulers had the upper hand. This development facilitated the coalescing of tribes into "great tribes," some of which under favorable conditions would later become tribal states. The communal and tribal democracy, with self-imposed contributions by the community members, survived in small entities and local territorial subunits the longest. On a larger scale, it was being replaced by the rule of able leaders and then dominant families, ultimately leading inevitably to hereditary transition of supreme power, mandatory taxation, service etc. When social and economic evolution reached this level, the concentration of power was facilitated and made possible to sustain by parallel development of a professional military force (called at this stage "drużyna") at the ruler's or chief's disposal.

Burials and religion

Burial customs, at least in southern Poland, included raising kurgans. The urn with the ashes was placed on the mound or on a post thrust into the ground. In that position, few such urns survived, which may be the reason why Slavic burial sites in Poland are rare. All dead, regardless of social status, were cremated and afforded a burial, according to

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

testimonies (one from the end of the 9th century and another one from about 930). A Slavic funeral feast practice was also mentioned earlier by

Theophylact Simocatta

Theophylact Simocatta (Byzantine Greek: Θεοφύλακτος Σιμοκάτ(τ)ης ''Theophýlaktos Simokát(t)ēs''; la, Theophylactus Simocatta) was an early seventh-century Byzantine historiographer, arguably ranking as the last historian o ...

.

According to

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

, the Slavs believed in one god, the creator of lightning and master of the entire universe, to whom all sacrificial animals (and sometimes people) were offered. The highest god was called

Svarog

Svarog is a Slavic god of fire and blacksmithing, who was once interpreted as a sky god on the basis of an etymology rejected by modern scholarship. He is mentioned in only one source, the ''Primary Chronicle'', which is problematic in interpret ...

throughout the Slavic area, but other gods were also worshiped in different regions at different times, often with local names. Natural objects such as rivers, groves or mountains were also celebrated, as well as nymphs, demons, ancestral and other spirits, who were all venerated and appeased by offering rituals, which also involved augury. Such beliefs and practices were later developed and individualized by the many Slavic tribes.

The Slavs erected sanctuaries, created statues and other sculptures, including the four-faced

Svetovid, whose carvings symbolize various aspects of the Slavic cosmology model. One 9th-century specimen from the

Zbruch River

The Zbruch ( uk, Збруч, pl, Zbrucz) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.[Збруч]

in modern Ukraine, found in 1848, is on display at the Archeological Museum in

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

. Many of the sacred locations and objects were identified outside Poland, for example in northeastern Germany or Ukraine. In Poland, religious activity sites have been investigated in northwestern Pomerania, including

Szczecin, where a three-headed deity once stood, and the

Wolin

Wolin (; formerly german: Wollin ) is the name both of a Polish island in the Baltic Sea, just off the Polish coast, and a town on that island. Administratively, the island belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. Wolin is separated from th ...

island, where 9th– to 11th-century cult figurines were found. Archeologically confirmed cult places and figures have also been researched at several other locations.

Early Slavic states and other 9th-century developments

Samo's realm

The first Slavic state-like entity, the realm of King

Samo

Samo (–) founded the first recorded political union of Slavic tribes, known as Samo's Empire (''realm'', ''kingdom'', or ''tribal union''), stretching from Silesia to present-day Slovakia, ruling from 623 until his death in 658. According to ...

, originally a

Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

trader, flourished close to Poland in

Bohemia and

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

, parts of

Pannonia and more southern regions between the

Oder and

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

rivers during the period 623–658. Samo became a Slavic leader by helping the Slavs defend themselves successfully against

Avar assailants. What Samo led was probably a loose alliance of tribes, and it fell apart after his death. Slavic

Carantania, centered on Krnski Grad (now

Karnburg

Maria Saal ( sl, Gospa Sveta) is a market town in the district of Klagenfurt-Land in the Austrian state of Carinthia. It is located in the east of the historic Zollfeld plain (''Gosposvetsko polje''), the wide valley of the Glan river. The muni ...

in

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

), was more of a real state, developed possibly from one part of the disintegrating Samo's kingdom, but lasted under a native dynasty throughout the 8th century and became

Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

.

Great Moravia and the establishment of a written Slavic language

Larger scale state-generating processes developed in Slavic areas in the 9th century.

Great Moravia

Great Moravia ( la, Regnum Marahensium; el, Μεγάλη Μοραβία, ''Meghálī Moravía''; cz, Velká Morava ; sk, Veľká Morava ; pl, Wielkie Morawy), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to ...

, the most prominent Slavic state of the era, became established in the early 9th century south of modern Poland. The original lands of Great Moravia included what is now

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

and western

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

, plus parts of

Bohemia,

Pannonia and southern regions of

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

. The glory of the Great Moravian empire became fully apparent in light of archeological discoveries; lavishly equipped burials are especially spectacular.

Such finds do not extend to the lands that now constitute southern Poland, however. The great territorial expansion of Great Moravia took place during the reign of

Svatopluk I

Svatopluk I or Svätopluk I, also known as Svatopluk the Great (Latin: ''Zuentepulc'', ''Zuentibald'', ''Sventopulch'', ''Zvataplug''; Old Church Slavic: Свѧтопълкъ and transliterated ''Svętopъłkъ''; Polish: ''Świętopełk''; Greek ...

at the end of the 9th century. The Moravian state collapsed quite suddenly; in 906, weakened by an internal crisis and

Magyar invasions, it ceased to exist entirely.

In 831,

Mojmir I was baptized, and his Moravian state became a part of the

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

n

Passau diocese. Aiming to achieve ecclesiastical as well as political independence from

East Frankish

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire int ...

influence, his successor

Rastislav

Rastislav or Rostyslav is a male Slavic given name, meaning "''to increase glory''" . The name has been used by several notable people of Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, Serbian, Czech and Slovak backgrounds.

*Old Slavonic, Serbian, Slovak, Slove ...

asked the Byzantine emperor

Michael III for missionaries. As a result,

Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wit ...

arrived in Moravia in 863 and commenced missionary activities among the Slavic people there. To further their goals, the brothers developed a written Slavic liturgical language:

Old Church Slavonic, which employed the

Glagolitic alphabet

The Glagolitic script (, , ''glagolitsa'') is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed to have been created in the 9th century by Saint Cyril, a monk from Thessalonica. He and his brother Saint Methodius were sent by the Byzan ...

created by them. They translated the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

and other church texts into this language, thus establishing a foundation for the later Slavic

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

churches.

The Czech state

The fall of Great Moravia made room for the expansion of the

Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

or

Bohemian state, which likewise incorporated some of the Polish lands. The founder of the

Přemyslid dynasty

The Přemyslid dynasty or House of Přemyslid ( cs, Přemyslovci, german: Premysliden, pl, Przemyślidzi) was a Bohemian royal dynasty that reigned in the Duchy of Bohemia and later Kingdom of Bohemia and Margraviate of Moravia (9th century–130 ...

, Prince

Bořivoj, was baptized by Methodius in the Slavic rite during the later part of the 9th century and settled in

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

. His son and successor

Spytihněv was baptized in

Regensburg in the Latin rite, which marks the early stage of

East Frankish

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire int ...

/German influence in Bohemian affairs, which was destined to be decisive. Borivoj's grandson Prince

Wenceslaus

Wenceslaus, Wenceslas, Wenzeslaus and Wenzslaus (and other similar names) are Latinized forms of the Czech name Václav. The other language versions of the name are german: Wenzel, pl, Wacław, Więcesław, Wieńczysław, es, Wenceslao, russian ...

, the future Czech martyr and patron saint, was killed, probably in 935, by his brother

Boleslaus. Boleslaus I solidified the power of the Prague princes and most likely dominated the

Vistulan and

Lendian tribes of Lesser Poland and at least parts of

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

.

9th-century Polish lands

In the 9th century the Polish lands were still on the peripheries of medieval Europe as regards its major powers and events, but a measure of progress did take place in levels of civilization, as evidenced by the number of gords built, kurgans raised and movable equipment used. The tribal elites must have been influenced by the relative closeness of the

Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

; objects crafted there have occasionally been found.

Poland was populated by many tribes of various sizes. The names of some of them, mostly from the western part of the country, are known from written sources, especially a

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

document written in the mid-9th century by the anonymous

Bavarian Geographer The epithet "Bavarian Geographer" ( la, Geographus Bavarus) is the conventional name for the anonymous author of a short Latin medieval text containing a list of the tribes in Central- Eastern Europe, headed ().

The name "Bavarian Geographer" was ...

. During this period, smaller tribal structures were disintegrating while larger ones were being established in their place.

Characteristic of the turn of the 10th century in most Polish tribal settlement areas was a particular intensification of

gord building activity. The gords were the centers of social and political life. Tribal leaders and elders had their headquarters in their protected environment and some of the tribal general assemblies took place inside them. Religious cult locations were commonly located in the vicinity, while the gords themselves were frequently visited by traders and artisans.

The Vistulan state

A major development of the 9th century period concerns the somewhat enigmatic Wiślanie, or

Vistulans

The Vistulans, or Vistulanians ( pl, Wiślanie), were an early medieval Lechitic tribe inhabiting the western part of modern Lesser Poland."The main tribe inhabiting the reaches of the Upper Vistula and its tributaries was the Vislane (Wislanie) ...

(Bavarian Geographer's ''Vuislane'') tribe. The Vistulans of western Lesser Poland, mentioned in several contemporary written sources, were already a large tribal union in the first half of the 9th century.

In the second half of the century, they were evolving into a super-tribal state until their efforts were terminated by more powerful neighbors from the south.

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, the main town of the Vistulans, with its

Wawel