Poison gas in World War I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The use of toxic chemicals as weapons dates back thousands of years, but the first large scale use of

The use of toxic chemicals as weapons dates back thousands of years, but the first large scale use of

The first instance of large-scale use of gas as a weapon was on 31 January 1915, when Germany fired 18,000

The first instance of large-scale use of gas as a weapon was on 31 January 1915, when Germany fired 18,000

It quickly became evident that the men who stayed in their places suffered less than those who ran away, as any movement worsened the effects of the gas, and that those who stood up on the fire step suffered less—indeed they often escaped any serious effects—than those who lay down or sat at the bottom of a trench. Men who stood on the parapet suffered least, as the gas was denser near the ground. The worst sufferers were the wounded lying on the ground, or on stretchers, and the men who moved back with the cloud. Chlorine was less effective as a weapon than the Germans had hoped, particularly as soon as simple countermeasures were introduced. The gas produced a visible greenish cloud and strong odour, making it easy to detect. It was water-soluble, so the simple expedient of covering the mouth and nose with a damp cloth was effective at reducing the effect of the gas. It was thought to be even more effective to use

It quickly became evident that the men who stayed in their places suffered less than those who ran away, as any movement worsened the effects of the gas, and that those who stood up on the fire step suffered less—indeed they often escaped any serious effects—than those who lay down or sat at the bottom of a trench. Men who stood on the parapet suffered least, as the gas was denser near the ground. The worst sufferers were the wounded lying on the ground, or on stretchers, and the men who moved back with the cloud. Chlorine was less effective as a weapon than the Germans had hoped, particularly as soon as simple countermeasures were introduced. The gas produced a visible greenish cloud and strong odour, making it easy to detect. It was water-soluble, so the simple expedient of covering the mouth and nose with a damp cloth was effective at reducing the effect of the gas. It was thought to be even more effective to use

The British expressed outrage at Germany's use of poison gas at Ypres and responded by developing their own gas warfare capability. The commander of II Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Ferguson, said of gas:

The first use of gas by the British was at the

The British expressed outrage at Germany's use of poison gas at Ypres and responded by developing their own gas warfare capability. The commander of II Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Ferguson, said of gas:

The first use of gas by the British was at the

On 29 June 1916, the

On 29 June 1916, the

Mustard gas is not an effective killing agent (though in high enough doses it is fatal) but can be used to harass and disable the enemy and pollute the battlefield. Delivered in artillery shells, mustard gas was heavier than air, and it settled to the ground as an oily liquid. Once in the soil, mustard gas remained active for several days, weeks, or even months, depending on the weather conditions.

The skin of victims of mustard gas blistered, their eyes became very sore and they began to vomit. Mustard gas caused internal and external bleeding and attacked the bronchial tubes, stripping off the mucous membrane. This was extremely painful. Fatally injured victims sometimes took four or five weeks to die of mustard gas exposure.

One nurse,

Mustard gas is not an effective killing agent (though in high enough doses it is fatal) but can be used to harass and disable the enemy and pollute the battlefield. Delivered in artillery shells, mustard gas was heavier than air, and it settled to the ground as an oily liquid. Once in the soil, mustard gas remained active for several days, weeks, or even months, depending on the weather conditions.

The skin of victims of mustard gas blistered, their eyes became very sore and they began to vomit. Mustard gas caused internal and external bleeding and attacked the bronchial tubes, stripping off the mucous membrane. This was extremely painful. Fatally injured victims sometimes took four or five weeks to die of mustard gas exposure.

One nurse,  The British Army first used mustard gas in November 1917 at Cambrai, after their armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard gas shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard gas weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on

The British Army first used mustard gas in November 1917 at Cambrai, after their armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard gas shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard gas weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on

The Geneva Protocol, signed by 132 nations on June 17, 1925, was a treaty established to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons during wartime. As stated by Coupland and Leins, "it was fostered in part by a 1918 appeal in which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) described the use of poisonous gas against soldiers as a barbarous invention which science is bringing to perfection". The Protocol required that all remaining stockpiles of chemical weapons be destroyed. Chemical warfare agents that contained bromine, nitroaromatic, and chlorine were dismantled and destroyed. The destruction and disposal of the chemicals did not consider the long-term and adverse impacts on the environment. Although the Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemical weapons during wartime, the Protocol did not ban the production of chemical weapons. In fact, since the Geneva Protocol, the stockpiling of chemical weapons has continued, and weapons have become more lethal. As a result, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) was drafted in 1993, which prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. Despite there being an international ban on chemical warfare, the CWC "allows domestic law enforcement agencies of the signing countries to use chemical weapons on their citizens".

The Geneva Protocol, signed by 132 nations on June 17, 1925, was a treaty established to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons during wartime. As stated by Coupland and Leins, "it was fostered in part by a 1918 appeal in which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) described the use of poisonous gas against soldiers as a barbarous invention which science is bringing to perfection". The Protocol required that all remaining stockpiles of chemical weapons be destroyed. Chemical warfare agents that contained bromine, nitroaromatic, and chlorine were dismantled and destroyed. The destruction and disposal of the chemicals did not consider the long-term and adverse impacts on the environment. Although the Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemical weapons during wartime, the Protocol did not ban the production of chemical weapons. In fact, since the Geneva Protocol, the stockpiling of chemical weapons has continued, and weapons have become more lethal. As a result, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) was drafted in 1993, which prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. Despite there being an international ban on chemical warfare, the CWC "allows domestic law enforcement agencies of the signing countries to use chemical weapons on their citizens".

Death by gas was often slow and painful. According to Denis Winter (''Death's Men'', 1978), a fatal dose of phosgene eventually led to "shallow breathing and retching, pulse up to 120, an ashen face and the discharge of four pints (2 litres) of yellow liquid from the lungs each hour for the 48 of the drowning spasms."

A common fate of those exposed to gas was blindness, chlorine gas or mustard gas being the main causes. One of the most famous First World War paintings, '' Gassed'' by John Singer Sargent, captures such a scene of mustard gas casualties which he witnessed at a dressing station at Le Bac-du-Sud near Arras in July 1918. (The gases used during that battle (tear gas) caused temporary blindness and/or a painful stinging in the eyes. These bandages were normally water-soaked to provide a rudimentary form of pain relief to the eyes of casualties before they reached more organized medical help.)

The proportion of mustard gas fatalities to total casualties was low; 2% of mustard gas casualties died and many of these succumbed to secondary infections rather than the gas itself. Once it was introduced at the

Death by gas was often slow and painful. According to Denis Winter (''Death's Men'', 1978), a fatal dose of phosgene eventually led to "shallow breathing and retching, pulse up to 120, an ashen face and the discharge of four pints (2 litres) of yellow liquid from the lungs each hour for the 48 of the drowning spasms."

A common fate of those exposed to gas was blindness, chlorine gas or mustard gas being the main causes. One of the most famous First World War paintings, '' Gassed'' by John Singer Sargent, captures such a scene of mustard gas casualties which he witnessed at a dressing station at Le Bac-du-Sud near Arras in July 1918. (The gases used during that battle (tear gas) caused temporary blindness and/or a painful stinging in the eyes. These bandages were normally water-soaked to provide a rudimentary form of pain relief to the eyes of casualties before they reached more organized medical help.)

The proportion of mustard gas fatalities to total casualties was low; 2% of mustard gas casualties died and many of these succumbed to secondary infections rather than the gas itself. Once it was introduced at the

None of the First World War's combatants were prepared for the introduction of poison gas as a weapon. Once gas was introduced, development of gas protection began and the process continued for much of the war producing a series of increasingly effective gas masks.

Even at Second Ypres, Germany, still unsure of the weapon's effectiveness, only issued breathing masks to the engineers handling the gas. At Ypres a Canadian medical officer, who was also a chemist, quickly identified the gas as chlorine and recommended that the troops urinate on a cloth and hold it over their mouth and nose, urine would be left to sit for a period so that the ammonia would activate, this would neutralize some of the chemicals in the chlorine gas, this action would allow them to delay the German advance at Ypres giving the allies time to reinforce the area when French and other colonial troops had retreated. The first official equipment issued was similarly crude; a pad of material, usually impregnated with a chemical, tied over the lower face. To protect the eyes from tear gas, soldiers were issued with gas goggles.

None of the First World War's combatants were prepared for the introduction of poison gas as a weapon. Once gas was introduced, development of gas protection began and the process continued for much of the war producing a series of increasingly effective gas masks.

Even at Second Ypres, Germany, still unsure of the weapon's effectiveness, only issued breathing masks to the engineers handling the gas. At Ypres a Canadian medical officer, who was also a chemist, quickly identified the gas as chlorine and recommended that the troops urinate on a cloth and hold it over their mouth and nose, urine would be left to sit for a period so that the ammonia would activate, this would neutralize some of the chemicals in the chlorine gas, this action would allow them to delay the German advance at Ypres giving the allies time to reinforce the area when French and other colonial troops had retreated. The first official equipment issued was similarly crude; a pad of material, usually impregnated with a chemical, tied over the lower face. To protect the eyes from tear gas, soldiers were issued with gas goggles.

The next advance was the introduction of the gas helmet—basically a bag placed over the head. The fabric of the bag was impregnated with a chemical to neutralize the gas—the chemical would wash out into the soldier's eyes whenever it rained. Eye-pieces, which were prone to fog up, were initially made from

The next advance was the introduction of the gas helmet—basically a bag placed over the head. The fabric of the bag was impregnated with a chemical to neutralize the gas—the chemical would wash out into the soldier's eyes whenever it rained. Eye-pieces, which were prone to fog up, were initially made from  Self-contained box respirators represented the culmination of gas mask development during the First World War. Box respirators used a two-piece design; a mouthpiece connected via a hose to a box

Self-contained box respirators represented the culmination of gas mask development during the First World War. Box respirators used a two-piece design; a mouthpiece connected via a hose to a box  Gas alert procedure became a routine for the front-line soldier. To warn of a gas attack, a bell would be rung, often made from a spent artillery shell. At the noisy batteries of the siege guns, a compressed air strombus horn was used, which could be heard nine miles (14 km) away. Notices would be posted on all approaches to an affected area, warning people to take precautions.

Other British attempts at countermeasures were not so effective. An early plan was to use 100,000 fans to disperse the gas. Burning coal or

Gas alert procedure became a routine for the front-line soldier. To warn of a gas attack, a bell would be rung, often made from a spent artillery shell. At the noisy batteries of the siege guns, a compressed air strombus horn was used, which could be heard nine miles (14 km) away. Notices would be posted on all approaches to an affected area, warning people to take precautions.

Other British attempts at countermeasures were not so effective. An early plan was to use 100,000 fans to disperse the gas. Burning coal or

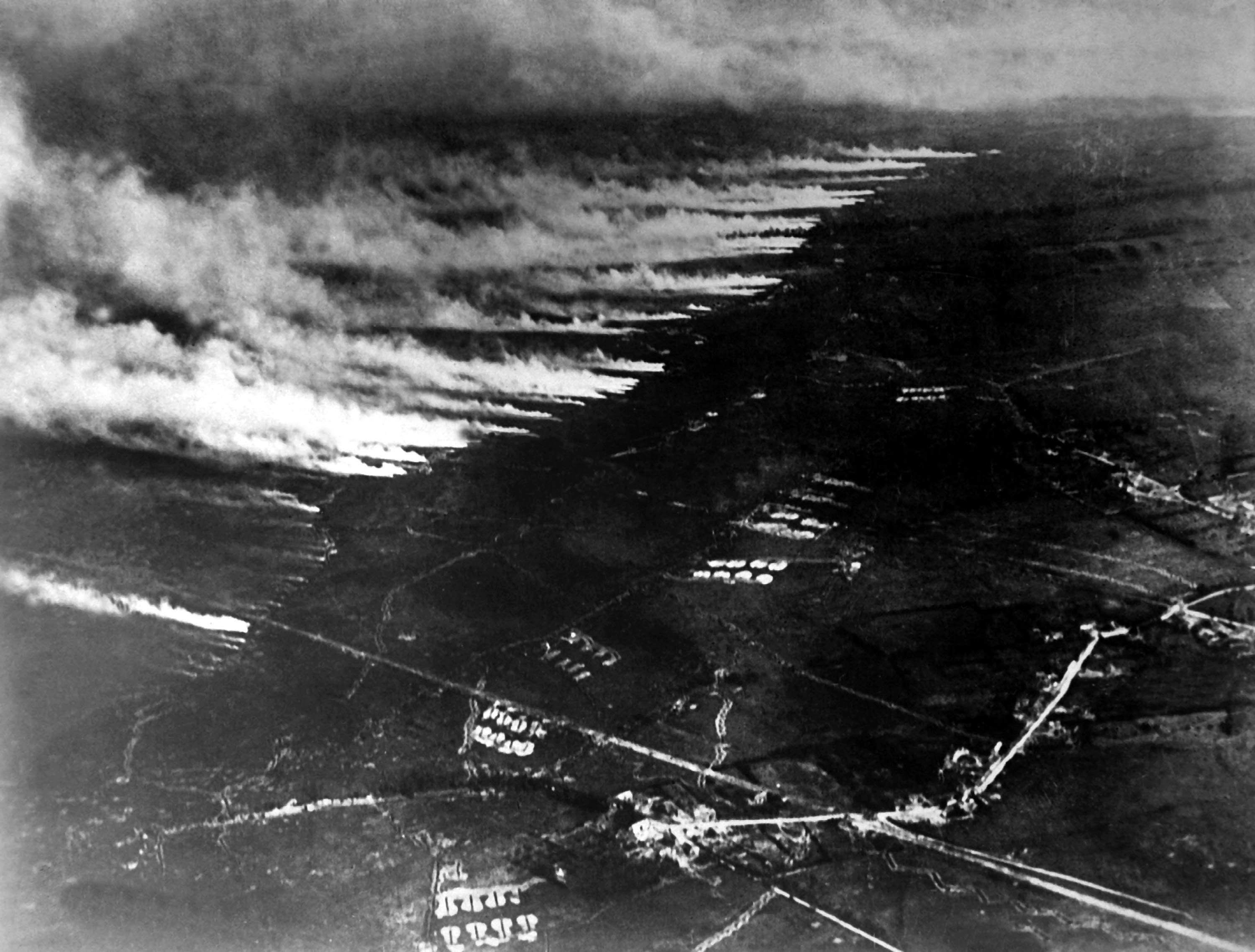

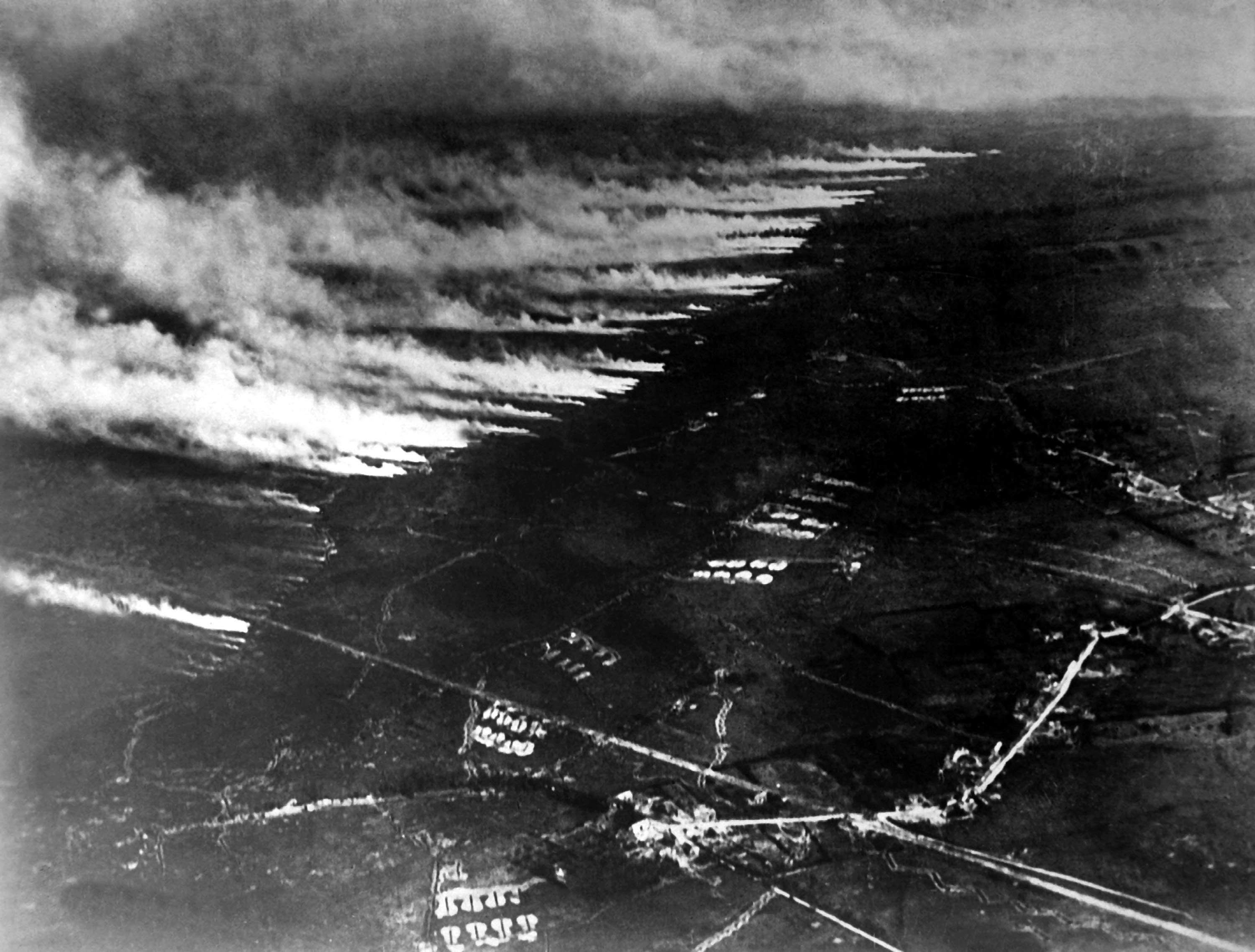

The first system employed for the mass delivery of gas involved releasing the gas cylinders in a favourable wind such that it was carried over the enemy's trenches. The Hague Convention of 1899 prohibited the use of poison gasses delivered by projectiles. The main advantage of this method was that it was relatively simple and, in suitable atmospheric conditions, produced a concentrated cloud capable of overwhelming the gas mask defences. The disadvantages of cylinder releases were numerous. First and foremost, delivery was at the mercy of the wind. If the wind was fickle, as was the case at Loos, the gas could backfire, causing friendly casualties. Gas clouds gave plenty of warning, allowing the enemy time to protect themselves, though many soldiers found the sight of a creeping gas cloud unnerving. Gas clouds had limited penetration, only capable of affecting the front-line trenches before dissipating.

Finally, the cylinders had to be emplaced at the very front of the trench system so that the gas was released directly over no man's land. This meant that the cylinders had to be manhandled through communication trenches, often clogged and sodden, and stored at the front where there was always the risk that cylinders would be prematurely breached during a bombardment. A leaking cylinder could issue a telltale wisp of gas that, if spotted, would be sure to attract shellfire.

The first system employed for the mass delivery of gas involved releasing the gas cylinders in a favourable wind such that it was carried over the enemy's trenches. The Hague Convention of 1899 prohibited the use of poison gasses delivered by projectiles. The main advantage of this method was that it was relatively simple and, in suitable atmospheric conditions, produced a concentrated cloud capable of overwhelming the gas mask defences. The disadvantages of cylinder releases were numerous. First and foremost, delivery was at the mercy of the wind. If the wind was fickle, as was the case at Loos, the gas could backfire, causing friendly casualties. Gas clouds gave plenty of warning, allowing the enemy time to protect themselves, though many soldiers found the sight of a creeping gas cloud unnerving. Gas clouds had limited penetration, only capable of affecting the front-line trenches before dissipating.

Finally, the cylinders had to be emplaced at the very front of the trench system so that the gas was released directly over no man's land. This meant that the cylinders had to be manhandled through communication trenches, often clogged and sodden, and stored at the front where there was always the risk that cylinders would be prematurely breached during a bombardment. A leaking cylinder could issue a telltale wisp of gas that, if spotted, would be sure to attract shellfire.

A British chlorine cylinder, known as an "oojah", weighed 190 lb (86 kg), of which 60 lb (27 kg) was chlorine gas, and required two men to carry. Phosgene gas was introduced later in a cylinder, known as a "mouse", that weighed 50 lb (23 kg).

Delivering gas via artillery shell overcame many of the risks of dealing with gas in cylinders. The Germans, for example, used artillery shells. Gas shells were independent of the wind and increased the effective range of gas, making anywhere within reach of the guns vulnerable. Gas shells could be delivered without warning, especially the clear, nearly odourless phosgene—there are numerous accounts of gas shells, landing with a "plop" rather than exploding, being initially dismissed as dud HE or shrapnel shells, giving the gas time to work before the soldiers were alerted and took precautions.

A British chlorine cylinder, known as an "oojah", weighed 190 lb (86 kg), of which 60 lb (27 kg) was chlorine gas, and required two men to carry. Phosgene gas was introduced later in a cylinder, known as a "mouse", that weighed 50 lb (23 kg).

Delivering gas via artillery shell overcame many of the risks of dealing with gas in cylinders. The Germans, for example, used artillery shells. Gas shells were independent of the wind and increased the effective range of gas, making anywhere within reach of the guns vulnerable. Gas shells could be delivered without warning, especially the clear, nearly odourless phosgene—there are numerous accounts of gas shells, landing with a "plop" rather than exploding, being initially dismissed as dud HE or shrapnel shells, giving the gas time to work before the soldiers were alerted and took precautions.

The main flaw associated with delivering gas via artillery was the difficulty of achieving a killing concentration. Each shell had a small gas payload and an area would have to be subjected to a saturation bombardment to produce a cloud to match cylinder delivery. Mustard gas did not need to form a concentrated cloud and hence artillery was the ideal vehicle for delivery of this battlefield pollutant.

The solution to achieving a lethal concentration without releasing from cylinders was the "gas projector", essentially a large-bore mortar that fired the entire cylinder as a missile. The British

The main flaw associated with delivering gas via artillery was the difficulty of achieving a killing concentration. Each shell had a small gas payload and an area would have to be subjected to a saturation bombardment to produce a cloud to match cylinder delivery. Mustard gas did not need to form a concentrated cloud and hence artillery was the ideal vehicle for delivery of this battlefield pollutant.

The solution to achieving a lethal concentration without releasing from cylinders was the "gas projector", essentially a large-bore mortar that fired the entire cylinder as a missile. The British

Over of France had to be cordoned off at the end of the war because of unexploded ordnance. About 20% of the chemical shells were duds, and approximately 13 million of these munitions were left in place. This has been a serious problem in former battle areas from immediately after the end of the War until the present. Shells may be, for instance, uncovered when farmers plough their fields (termed the ' iron harvest'), and are also regularly discovered when public works or construction work is done. After the armistice, people sought unexploded weapons for their metal value, as well as preventing the danger that they posed to civilians. Toxic chemicals were emptied from shells, resulting in many deaths and health defects.

Another difficulty is the current stringency of environmental legislation. In the past, a common method of getting rid of unexploded chemical ammunition was to detonate or dump it at sea; this is currently prohibited in most countries.See the

Over of France had to be cordoned off at the end of the war because of unexploded ordnance. About 20% of the chemical shells were duds, and approximately 13 million of these munitions were left in place. This has been a serious problem in former battle areas from immediately after the end of the War until the present. Shells may be, for instance, uncovered when farmers plough their fields (termed the ' iron harvest'), and are also regularly discovered when public works or construction work is done. After the armistice, people sought unexploded weapons for their metal value, as well as preventing the danger that they posed to civilians. Toxic chemicals were emptied from shells, resulting in many deaths and health defects.

Another difficulty is the current stringency of environmental legislation. In the past, a common method of getting rid of unexploded chemical ammunition was to detonate or dump it at sea; this is currently prohibited in most countries.See the

After World War I, the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom and other nations had stockpiles of unfired weapons. It has been estimated that 125 million tons of toxic gases were used to manufacture bombs, grenades and shells. The remaining weapons were destroyed, dismantled, and disposed of in oceans and seas. It was believed that the chemicals would be diluted when disposed of in the ocean, and therefore ocean and sea dumping was a “safe and convenient” practice. Hundreds of thousands of tons of chemical agents, such as sulphur mustard, cyanogen chloride and arsine oil, were disposed of at sea. Chemical weapons have since washed up on shorelines and been found by fishers, causing injuries and, in some cases, death. Other disposal methods included land burials and incineration. After World War 1, “chemical shells made up 35 percent of French and German ammunition supplies, 25 percent British and 20 percent American”. Weapons that contained chemicals such as bromine, chlorine and nitroaromatic were burned. The thermal destruction of chemical weapons negatively impacted the ecological environment of disposal sites. For example, in Verdun, France, the thermal destruction of weapons “resulted in severe metal contamination of upper 4-10 cm of topsoil” at the Place à Gas disposal site.

After World War I, the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom and other nations had stockpiles of unfired weapons. It has been estimated that 125 million tons of toxic gases were used to manufacture bombs, grenades and shells. The remaining weapons were destroyed, dismantled, and disposed of in oceans and seas. It was believed that the chemicals would be diluted when disposed of in the ocean, and therefore ocean and sea dumping was a “safe and convenient” practice. Hundreds of thousands of tons of chemical agents, such as sulphur mustard, cyanogen chloride and arsine oil, were disposed of at sea. Chemical weapons have since washed up on shorelines and been found by fishers, causing injuries and, in some cases, death. Other disposal methods included land burials and incineration. After World War 1, “chemical shells made up 35 percent of French and German ammunition supplies, 25 percent British and 20 percent American”. Weapons that contained chemicals such as bromine, chlorine and nitroaromatic were burned. The thermal destruction of chemical weapons negatively impacted the ecological environment of disposal sites. For example, in Verdun, France, the thermal destruction of weapons “resulted in severe metal contamination of upper 4-10 cm of topsoil” at the Place à Gas disposal site.

Soldiers who claimed to have been exposed to chemical warfare have often presented unusual medical conditions which has led to much controversy. The lack of information has left doctors, patients, and their families in the dark in terms of prognosis and treatment. Nerve agents such as sarin, tabun, and soman are believed to have the most significant long-term health effects. Chronic fatigue and memory loss have been reported to last up to three years after exposure. In the years following World War One, there were many conferences held in attempts to abolish the use of chemical weapons altogether, such as the

Soldiers who claimed to have been exposed to chemical warfare have often presented unusual medical conditions which has led to much controversy. The lack of information has left doctors, patients, and their families in the dark in terms of prognosis and treatment. Nerve agents such as sarin, tabun, and soman are believed to have the most significant long-term health effects. Chronic fatigue and memory loss have been reported to last up to three years after exposure. In the years following World War One, there were many conferences held in attempts to abolish the use of chemical weapons altogether, such as the

Gas Warfare

in

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20100919085218/http://cbwinfo.com/History/WWI.html Chemical Weapons in World War I

Gas Warfare

effects of chlorine gas poisoning

Understanding Chemical Weapons in the First World War

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chemical weapons in World War I

The use of toxic chemicals as weapons dates back thousands of years, but the first large scale use of

The use of toxic chemicals as weapons dates back thousands of years, but the first large scale use of chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

s was during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill entrenched defenders, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective. The types of weapons employed ranged from disabling chemicals, such as tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

, to lethal agents like phosgene, chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

, and mustard gas. This chemical warfare was a major component of the first global war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

and first total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

of the 20th century. The killing capacity of gas was limited, with about 90,000 fatalities from a total of 1.3 million casualties caused by gas attack

Chemical warfare (CW) involves using the toxic properties of chemical substances as weapons. This type of warfare is distinct from nuclear warfare, biological warfare and radiological warfare, which together make up CBRN, the military acronym ...

s. Gas was unlike most other weapons of the period because it was possible to develop countermeasures, such as gas masks. In the later stages of the war, as the use of gas increased, its overall effectiveness diminished. The widespread use of these agents of chemical warfare, and wartime advances in the composition of high explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

, gave rise to an occasionally expressed view of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

as "the chemist's war" and also the era where weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natu ...

were created.

The use of poison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perman ...

by all major belligerents throughout World War I constituted war crimes as its use violated the 1899 Hague Declaration Concerning Asphyxiating Gases and the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, which prohibited the use of "poison or poisoned weapons" in warfare. Widespread horror and public revulsion at the use of gas and its consequences led to far less use of chemical weapons by combatants during World War II.

History of poison gas in World War I

1914: Tear gas

The most frequently used chemicals during World War I were tear-inducing irritants rather than fatal or disabling poisons. DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Force ...

was the first to employ tear gas, using 26 mm grenades filled with ethyl bromoacetate in August 1914. The small quantities of gas delivered, roughly per cartridge, were not even detected by the Germans. The stocks were rapidly consumed and by November a new order was placed by the French military. As bromine

Bromine is a chemical element with the symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is the third-lightest element in group 17 of the periodic table ( halogens) and is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a simi ...

was scarce among the Entente allies, the active ingredient was changed to chloroacetone

Chloroacetone is a chemical compound with the chemical formula, formula . At Standard conditions for temperature and pressure, STP it is a colourless liquid with a pungent odour. On exposure to light, it turns to a dark yellow-amber colour. It wa ...

.

In October 1914, German troops fired fragmentation shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

s filled with a chemical irritant against British positions at Neuve Chapelle; the concentration achieved was so small that it too was barely noticed.

None of the combatants considered the use of tear gas to be in conflict with the Hague Treaty of 1899, which specifically prohibited the launching of projectiles containing asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects primarily the tissues and organs. There are many circumstances that ca ...

ting or poisonous gas.

1915: Large-scale use and lethal gases

The first instance of large-scale use of gas as a weapon was on 31 January 1915, when Germany fired 18,000

The first instance of large-scale use of gas as a weapon was on 31 January 1915, when Germany fired 18,000 artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

shells containing liquid xylyl bromide

Xylyl bromide, also known as methylbenzyl bromide or T-stoff ('substance-T'), is any member or a mixture of organic chemical compounds with the molecular formula C6 H4(CH3)(CH2 Br). The mixture was formerly used as a tear gas and has an odor r ...

tear gas on Russian positions on the Rawka River

The Rawka River is a river in central Poland, a right tributary of the Bzura river (which it meets between Łowicz

Łowicz is a town in central Poland with 27,896 inhabitants (2020). It is situated in the Łódź Voivodeship (since 1999); p ...

, west of Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

during the Battle of Bolimov. Instead of vaporizing, the chemical froze and failed to have the desired effect.

The first killing agent was chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

, used by the German military. Chlorine is a powerful irritant that can inflict damage to the eyes, nose, throat and lungs. At high concentrations and prolonged exposure it can cause death by asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects primarily the tissues and organs. There are many circumstances that ca ...

tion. German chemical companies BASF

BASF SE () is a German multinational chemical company and the largest chemical producer in the world. Its headquarters is located in Ludwigshafen, Germany.

The BASF Group comprises subsidiaries and joint ventures in more than 80 countries ...

, Hoechst and Bayer (which formed the IG Farben conglomerate in 1925) had been making chlorine as a by-product of their dye manufacturing. In cooperation with Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber (; 9 December 186829 January 1934) was a German chemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber–Bosch process, a method used in industry to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen gas and hydroge ...

of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (German: ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften'') was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over by ...

for Chemistry in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, they began developing methods of discharging chlorine gas against enemy trench

A trench is a type of excavation or in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a wider gully, or ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit).

In geology, trenches result from ero ...

es.

It may appear from a ''feldpost'' letter of Major Karl von Zingler that the first chlorine gas attack by German forces took place before 2 January 1915: "In other war theatres it does not go better and it has been said that our Chlorine is very effective. 140 English officers have been killed. This is a horrible weapon ...". This letter must be discounted as evidence for early German use of chlorine, however, because the date "2 January 1915" may have been hastily scribbled instead of the intended "2 January 1916," the sort of common typographical error that is often made at the beginning of a new year. The deaths of so many English officers from gas at this time would certainly have been met with outrage, but a recent, extensive study of British reactions to chemical warfare says nothing of this supposed attack. Perhaps this letter was referring to the chlorine-phosgene attack on British troops at Wieltje near Ypres, on 19 December 1915 (see below).

By 22 April 1915, the German Army had 168 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s of chlorine deployed in 5,730 cylinders from Langemark-Poelkapelle

Langemark-Poelkapelle () is a municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders.

Geography

Other places in the municipality include Bikschote, Langemark and Poelkapelle. On January 1, 2006, Langemark-Poelkapelle had a total populati ...

, north of Ypres

Ypres ( , ; nl, Ieper ; vls, Yper; german: Ypern ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality c ...

. At 17:30, in a slight easterly breeze, the liquid chlorine was siphoned from the tanks, producing gas which formed a grey-green cloud that drifted across positions held by French Colonial troops from Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

, as well as the 1st Tirailleurs

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French ...

and the 2nd Zouaves

The Zouaves were a class of light infantry regiments of the French Army serving between 1830 and 1962 and linked to French North Africa; as well as some units of other countries modelled upon them. The zouaves were among the most decorated unit ...

from Algeria. Faced with an unfamiliar threat these troops broke ranks, abandoning their trenches and creating an 8,000-yard (7 km) gap in the Allied line. The German infantry were also wary of the gas and, lacking reinforcements, failed to exploit the break before the 1st Canadian Division

The 1st Canadian Division (French: ''1re Division du Canada'' ) is a joint operational command and control formation based at CFB Kingston, and falls under Canadian Joint Operations Command. It is a high-readiness unit, able to move on very shor ...

and assorted French troops reformed the line in scattered, hastily prepared positions apart. The Entente governments claimed the attack was a flagrant violation of international law but Germany argued that the Hague treaty had only banned chemical shells, rather than the use of gas projectors.

In what became the Second Battle of Ypres

During the First World War, the Second Battle of Ypres was fought from for control of the tactically important high ground to the east and south of the Flemish town of Ypres in western Belgium. The First Battle of Ypres had been fought the pr ...

, the Germans used gas on three more occasions; on 24 April against the 1st Canadian Division, on 2 May near Mouse Trap Farm and on 5 May against the British at Hill 60. The British Official History stated that at Hill 60, "90 men died from gas poisoning in the trenches or before they could be got to a dressing station; of the 207 brought to the nearest dressing stations, 46 died almost immediately and 12 after long suffering."

On 6 August, German troops under Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

used chlorine gas against Russian troops defending Osowiec Fortress

Osowiec Fortress ( Polish: ''Twierdza Osowiec'', Russian: ''Крепость Осовец'') is a 19th-century fortress built by the Russian Empire, located in what is now north-eastern Poland. It saw heavy fighting during World War I when i ...

. Surviving defenders drove back the attack and retained the fortress. The event would later be called the Attack of the Dead Men.

Germany used chemical weapons on the Eastern Front in an attack at Rawka (river)

The Rawka River is a river in central Poland, a right tributary of the Bzura river (which it meets between Łowicz and Sochaczew

Sochaczew () is a town in central Poland, with 38,300 inhabitants (2004). In the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), ...

, west of Warsaw. The Russian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �ВSukhoputnyye voyska V}), also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Force ...

took 9,000 casualties, with more than 1,000 fatalities. In response, the artillery branch of the Russian Army organised a commission to study the delivery of poison gas in shells.

Effectiveness and countermeasures

It quickly became evident that the men who stayed in their places suffered less than those who ran away, as any movement worsened the effects of the gas, and that those who stood up on the fire step suffered less—indeed they often escaped any serious effects—than those who lay down or sat at the bottom of a trench. Men who stood on the parapet suffered least, as the gas was denser near the ground. The worst sufferers were the wounded lying on the ground, or on stretchers, and the men who moved back with the cloud. Chlorine was less effective as a weapon than the Germans had hoped, particularly as soon as simple countermeasures were introduced. The gas produced a visible greenish cloud and strong odour, making it easy to detect. It was water-soluble, so the simple expedient of covering the mouth and nose with a damp cloth was effective at reducing the effect of the gas. It was thought to be even more effective to use

It quickly became evident that the men who stayed in their places suffered less than those who ran away, as any movement worsened the effects of the gas, and that those who stood up on the fire step suffered less—indeed they often escaped any serious effects—than those who lay down or sat at the bottom of a trench. Men who stood on the parapet suffered least, as the gas was denser near the ground. The worst sufferers were the wounded lying on the ground, or on stretchers, and the men who moved back with the cloud. Chlorine was less effective as a weapon than the Germans had hoped, particularly as soon as simple countermeasures were introduced. The gas produced a visible greenish cloud and strong odour, making it easy to detect. It was water-soluble, so the simple expedient of covering the mouth and nose with a damp cloth was effective at reducing the effect of the gas. It was thought to be even more effective to use urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and in many other animals. Urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder. Urination results in urine being excreted from the body through the urethra.

Cellular ...

rather than water, as it was known at the time that chlorine reacted with urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

(present in urine) to form dichloro urea.

Chlorine required a concentration of 1,000 parts per million to be fatal, destroying tissue in the lungs, likely through the formation of hypochlorous and hydrochloric acids when dissolved in the water in the lungs. Despite its limitations, chlorine was an effective psychological weapon—the sight of an oncoming cloud of the gas was a continual source of dread for the infantry.

Countermeasures were quickly introduced in response to the use of chlorine. The Germans issued their troops with small gauze pads filled with cotton waste, and bottles of a bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial biochem ...

solution with which to dampen the pads. Immediately following the use of chlorine gas by the Germans, instructions were sent to British and French troops to hold wet handkerchiefs or cloths over their mouths. Simple pad respirators similar to those issued to German troops were soon proposed by Lieutenant-Colonel N. C. Ferguson, the Assistant Director Medical Services of the 28th Division. These pads were intended to be used damp, preferably dipped into a solution of bicarbonate kept in buckets for that purpose; other liquids were also used. Because such pads could not be expected to arrive at the front for several days, army divisions set about making them for themselves. Locally available muslin, flannel and gauze were used, officers were sent to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

to buy more and local French women were employed making up rudimentary pads with string ties. Other units used lint bandages manufactured in the convent at Poperinge

Poperinge (; french: Poperinghe, ; vls, Poperienge) is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders, Flemish Region, and has a history going back to medieval times. The municipality comprises the town of Poperinge pr ...

. Pad respirators were sent up with rations to British troops in the line as early as the evening of 24 April.

In Britain the '' Daily Mail'' newspaper encouraged women to manufacture cotton pads, and within one month a variety of pad respirators were available to British and French troops, along with motoring goggles to protect the eyes. The response was enormous and a million gas masks were produced in a day. The ''Mail''s design was useless when dry and caused suffocation when wet—the respirator was responsible for the deaths of scores of men. By 6 July 1915, the entire British army was equipped with the more effective " smoke helmet" designed by Major Cluny MacPherson

Ewen MacPherson of Cluny, also known as "Cluny Macpherson" (11 February 1706 – 30 January 1764), was the Chief of Clan MacPherson during the Jacobite Rising of 1745. He took part as a leading supporter of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. After th ...

, Newfoundland Regiment

The Royal Newfoundland Regiment (R NFLD R) is a Primary Reserve infantry regiment of the Canadian Army. It is part of the 5th Canadian Division's 37 Canadian Brigade Group.

Predecessor units trace their origins to 1795, and since 1949 Royal New ...

, which was a flannel bag with a celluloid window, which entirely covered the head. The race was then on between the introduction of new and more effective poison gases and the production of effective countermeasures, which marked gas warfare until the armistice in November 1918.Edmonds and Wynne (1927): p. 217.

British gas attacks

The British expressed outrage at Germany's use of poison gas at Ypres and responded by developing their own gas warfare capability. The commander of II Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Ferguson, said of gas:

The first use of gas by the British was at the

The British expressed outrage at Germany's use of poison gas at Ypres and responded by developing their own gas warfare capability. The commander of II Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Ferguson, said of gas:

The first use of gas by the British was at the Battle of Loos

The Battle of Loos took place from 1915 in France on the Western Front, during the First World War. It was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. Th ...

, 25 September 1915, but the attempt was a disaster. Chlorine, codenamed ''Red Star'', was the agent to be used (140 tons arrayed in 5,100 cylinders), and the attack was dependent on a favourable wind. On this occasion the wind proved fickle, and the gas either lingered in no man's land or, in places, blew back on the British trenches. This was compounded when the gas could not be released from all the British canisters because the wrong turning keys were sent with them. Subsequent retaliatory German shelling hit some of those unused full cylinders, releasing gas among the British troops. Exacerbating the situation were the primitive flannel gas masks distributed to the British. The masks got hot, and the small eye-pieces misted over, reducing visibility. Some of the troops lifted the masks to get fresh air, causing them to be gassed.

1915: More deadly gases

The deficiencies of chlorine were overcome with the introduction of phosgene, which was prepared by a group of French chemists led byVictor Grignard

Francois Auguste Victor Grignard (6 May 1871 – 13 December 1935) was a French chemist who won the Nobel Prize for his discovery of the eponymously named Grignard reagent and Grignard reaction, both of which are important in the formation of c ...

and first used by France in 1915. Colourless and having an odour likened to "mouldy hay," phosgene was difficult to detect, making it a more effective weapon. Phosgene was sometimes used on its own, but was more often used mixed with an equal volume of chlorine, with the chlorine helping to spread the denser phosgene. The Allies called this combination ''White Star'' after the marking painted on shells containing the mixture.

Phosgene was a potent killing agent, deadlier than chlorine. It had a potential drawback in that some of the symptoms of exposure took 24 hours or more to manifest. This meant that the victims were initially still capable of putting up a fight; this could also mean that apparently fit troops would be incapacitated by the effects of the gas on the following day.

In the first combined chlorine–phosgene attack by Germany, against British troops at Wieltje near Ypres, Belgium on 19 December 1915, 88 tons of the gas were released from cylinders causing 1069 casualties and 69 deaths. The British P gas helmet, issued at the time, was impregnated with sodium phenolate

Sodium phenoxide (sodium phenolate) is an organic compound with the formula NaOC6H5. It is a white crystalline solid. Its anion, phenoxide, also known as phenolate, is the conjugate base of phenol. It is used as a precursor to many other organic ...

and partially effective against phosgene. The modified PH Gas Helmet, which was impregnated with phenate hexamine and hexamethylene tetramine (urotropine) to improve the protection against phosgene, was issued in January 1916.

Around 36,600 tons of phosgene were manufactured during the war, out of a total of 190,000 tons for all chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

s, making it second only to chlorine (93,800 tons) in the quantity manufactured:

* Germany 18,100 tons

* France 15,700 tons

* United Kingdom 1,400 tons (also used French stocks)

* United States 1,400 tons (also used French stocks)

Phosgene was never as notorious in public consciousness as mustard gas, but it killed far more people: about 85% of the 90,000 deaths caused by chemical weapons during World War I.

1916: Austrian use

On 29 June 1916, the

On 29 June 1916, the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army (, literally "Ground Forces of the Austro-Hungarians"; , literally "Imperial and Royal Army") was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint arm ...

attacked the Royal Italian Army's lines on Monte San Michele with a mix of phosgene and chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

gas. Thousands of Italian soldiers died in this first chemical weapons attack on the Italian Front.

1917: Mustard gas

The most widely reported chemical agent of the First World War was mustard gas. It is a volatile oily liquid. It was introduced as avesicant

A blister agent (or vesicant), is a chemical compound that causes severe skin, eye and mucosal pain and irritation. They are named for their ability to cause severe chemical burns, resulting in painful water blisters on the bodies of those affe ...

by Germany on July 12, 1917, weeks prior to the Third Battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

. The Germans marked their shells yellow for mustard gas and green for chlorine and phosgene; hence they called the new gas ''Yellow Cross''. It was known to the British as ''HS'' (''Hun Stuff''), and the French called it ''Yperite'' (named after Ypres

Ypres ( , ; nl, Ieper ; vls, Yper; german: Ypern ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality c ...

).

Mustard gas is not an effective killing agent (though in high enough doses it is fatal) but can be used to harass and disable the enemy and pollute the battlefield. Delivered in artillery shells, mustard gas was heavier than air, and it settled to the ground as an oily liquid. Once in the soil, mustard gas remained active for several days, weeks, or even months, depending on the weather conditions.

The skin of victims of mustard gas blistered, their eyes became very sore and they began to vomit. Mustard gas caused internal and external bleeding and attacked the bronchial tubes, stripping off the mucous membrane. This was extremely painful. Fatally injured victims sometimes took four or five weeks to die of mustard gas exposure.

One nurse,

Mustard gas is not an effective killing agent (though in high enough doses it is fatal) but can be used to harass and disable the enemy and pollute the battlefield. Delivered in artillery shells, mustard gas was heavier than air, and it settled to the ground as an oily liquid. Once in the soil, mustard gas remained active for several days, weeks, or even months, depending on the weather conditions.

The skin of victims of mustard gas blistered, their eyes became very sore and they began to vomit. Mustard gas caused internal and external bleeding and attacked the bronchial tubes, stripping off the mucous membrane. This was extremely painful. Fatally injured victims sometimes took four or five weeks to die of mustard gas exposure.

One nurse, Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (29 December 1893 – 29 March 1970) was an English Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, writer, feminist, socialist and pacifist. Her best-selling 1933 memoir '' Testament of Youth'' recounted her experiences during the Fir ...

, wrote: "I wish those people who talk about going on with this war whatever it costs could see the soldiers suffering from mustard gas poisoning. Great mustard-coloured blisters, blind eyes, all sticky and stuck together, always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke."

The polluting nature of mustard gas meant that it was not always suitable for supporting an attack as the assaulting infantry would be exposed to the gas when they advanced. When Germany launched Operation Michael

Operation Michael was a major German military offensive during the First World War that began the German Spring Offensive on 21 March 1918. It was launched from the Hindenburg Line, in the vicinity of Saint-Quentin, France. Its goal was t ...

on 21 March 1918, they saturated the Flesquières salient with mustard gas instead of attacking it directly, believing that the harassing effect of the gas, coupled with threats to the salient's flanks, would make the British position untenable.

Gas never reproduced the dramatic success of 22 April 1915; it became a standard weapon which, combined with conventional artillery, was used to support most attacks in the later stages of the war. Gas was employed primarily on the Western Front—the static, confined trench system was ideal for achieving an effective concentration. Germany also used gas against Russia on the Eastern Front, where the lack of effective countermeasures resulted in deaths of over 56,000 Russians, while Britain experimented with gas in Palestine during the Second Battle of Gaza

The Second Battle of Gaza was fought on 17-19 April 1917, following the defeat of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) at the First Battle of Gaza in March, during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War. Gaza was defended by ...

. Russia began manufacturing chlorine gas in 1916, with phosgene being produced later in the year. Most of the manufactured gas was never used.

The British Army first used mustard gas in November 1917 at Cambrai, after their armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard gas shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard gas weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on

The British Army first used mustard gas in November 1917 at Cambrai, after their armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard gas shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard gas weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on Avonmouth Docks

The Avonmouth Docks are part of the Port of Bristol, in England. They are situated on the northern side of the mouth of the River Avon, opposite the Royal Portbury Dock on the southern side, where the river joins the Severn estuary, within Avo ...

. (The only option available to the British was the Despretz–Niemann–Guthrie process.) This was used first in September 1918 during the breaking of the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (German: , Siegfried Position) was a German defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. In 1916 ...

with the Hundred Days' Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Central Powers ...

.

The Allies mounted more gas attacks than the Germans in 1917 and 1918 because of a marked increase in production of gas from the Allied nations. Germany was unable to keep up with this pace despite creating various new gases for use in battle, mostly as a result of very costly methods of production. Entry into the war by the United States allowed the Allies to increase mustard gas production far more than Germany. Also the prevailing wind

Wind is the natural movement of air or other gases relative to a planet's surface. Winds occur on a range of scales, from thunderstorm flows lasting tens of minutes, to local breezes generated by heating of land surfaces and lasting a few ho ...

on the Western Front was blowing from west to east, which meant the Allies more frequently had favourable conditions for a gas release than did the Germans.

When the United States entered the war, it was already mobilizing resources from academic, industry and military sectors for research and development into poison gas. A Subcommittee on Noxious Gases was created by the National Research Committee, a major research centre was established at Camp American University, and the 1st Gas Regiment was recruited. The 1st Gas Regiment eventually served in France, where it used phosgene gas in several attacks. The Artillery used mustard gas with significant effect during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on at least three occasions. The United States began large-scale production of an improved vesicant gas known as Lewisite, for use in an offensive planned for early 1919. By the time of the armistice on 11 November, a plant near Willoughby, Ohio

Willoughby is a city in Lake County, Ohio and is a suburb of Cleveland. The population was 22,268 at the time of the 2010 census.

History

Willoughby's first permanent settler was David Abbott in 1798, who operated a gristmill. Abbott and his ...

was producing 10 tons per day of the substance, for a total of about 150 tons. It is uncertain what effect this new chemical would have had on the battlefield, as it degrades in moist conditions.

Post-war

By the end of the war, chemical weapons had lost much of their effectiveness against well trained and equipped troops. At that time, chemical weapon agents inflicted an estimated 1.3 million casualties. Nevertheless, in the following years, chemical weapons were used in several, mainly colonial, wars where one side had an advantage in equipment over the other. The British used poison gas, possiblyadamsite

Adamsite or DM is an organic compound; technically, an arsenical diphenylaminechlorarsine, that can be used as a riot control agent. DM belongs to the group of chemical warfare agents known as vomiting agents or sneeze gases. First synthesized in ...

, against Russian revolutionary troops beginning on 27 August 1919 and contemplated using chemical weapons against Iraqi insurgents in the 1920s; Bolshevik troops used poison gas to suppress the Tambov Rebellion

The Tambov Rebellion of 1920–1921 was one of the largest and best-organized peasant rebellions challenging the Bolshevik government during the Russian Civil War. The uprising took place in the territories of the modern Tambov Oblast and part ...

in 1920, Spain used chemical weapons in Morocco against Rif

The Rif or Riff (, ), also called Rif Mountains, is a geographic region in northern Morocco. This mountainous and fertile area is bordered by Cape Spartel and Tangier to the west, by Berkane and the Moulouya River to the east, by the Mediterrane ...

tribesmen throughout the 1920s and Italy used mustard gas in Libya in 1930 and again during its invasion of Ethiopia in 1936. In 1925, a Chinese warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

, Zhang Zuolin

Zhang Zuolin (; March 19, 1875 June 4, 1928), courtesy name Yuting (雨亭), nicknamed Zhang Laogang (張老疙瘩), was an influential Chinese bandit, soldier, and warlord during the Warlord Era in China. The warlord of Manchuria from 1916 to ...

, contracted a German company to build him a mustard gas plant in Shenyang, which was completed in 1927.

Public opinion had by then turned against the use of such weapons which led to the Geneva Protocol

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in ...

, an updated and extensive prohibition of poison weapons. The Protocol, which was signed by most First World War combatants in 1925, bans the use (but not the stockpiling) of lethal gas and bacteriological weapons. Most countries that signed ratified it within around five years; a few took much longer—Brazil, Japan, Uruguay, and the United States did not do so until the 1970s, and Nicaragua ratified it in 1990. The signatory nations agreed not to use poison gas in the future, stating "the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of all analogous liquids, materials or devices, has been justly condemned by the general opinion of the civilized world."

Chemical weapons have been used in at least a dozen wars since the end of the First World War; they were not used in combat on a large scale until Iraq used mustard gas and the more deadly nerve agents in the Halabja chemical attack

The Halabja massacre ( ku, Kêmyabarana Helebce کیمیابارانی ھەڵەبجە), also known as the Halabja chemical attack, was a massacre of Kurdish people that took place on 16 March 1988, during the closing days of the Iran–Iraq War ...

near the end of the eight-year Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Ba'athist Iraq, Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations S ...

. The full conflict's use of such weaponry killed around 20,000 Iranian troops (and injured another 80,000), around a quarter of the number of deaths caused by chemical weapons during the First World War.

The Geneva Protocol, 1925

The Geneva Protocol, signed by 132 nations on June 17, 1925, was a treaty established to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons during wartime. As stated by Coupland and Leins, "it was fostered in part by a 1918 appeal in which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) described the use of poisonous gas against soldiers as a barbarous invention which science is bringing to perfection". The Protocol required that all remaining stockpiles of chemical weapons be destroyed. Chemical warfare agents that contained bromine, nitroaromatic, and chlorine were dismantled and destroyed. The destruction and disposal of the chemicals did not consider the long-term and adverse impacts on the environment. Although the Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemical weapons during wartime, the Protocol did not ban the production of chemical weapons. In fact, since the Geneva Protocol, the stockpiling of chemical weapons has continued, and weapons have become more lethal. As a result, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) was drafted in 1993, which prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. Despite there being an international ban on chemical warfare, the CWC "allows domestic law enforcement agencies of the signing countries to use chemical weapons on their citizens".

The Geneva Protocol, signed by 132 nations on June 17, 1925, was a treaty established to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons during wartime. As stated by Coupland and Leins, "it was fostered in part by a 1918 appeal in which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) described the use of poisonous gas against soldiers as a barbarous invention which science is bringing to perfection". The Protocol required that all remaining stockpiles of chemical weapons be destroyed. Chemical warfare agents that contained bromine, nitroaromatic, and chlorine were dismantled and destroyed. The destruction and disposal of the chemicals did not consider the long-term and adverse impacts on the environment. Although the Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemical weapons during wartime, the Protocol did not ban the production of chemical weapons. In fact, since the Geneva Protocol, the stockpiling of chemical weapons has continued, and weapons have become more lethal. As a result, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) was drafted in 1993, which prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. Despite there being an international ban on chemical warfare, the CWC "allows domestic law enforcement agencies of the signing countries to use chemical weapons on their citizens".

Effect on World War II

All major combatants stockpiled chemical weapons during theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, but the only reports of its use in the conflict were the Japanese use of relatively small amounts of mustard gas and lewisite in China, Italy's use of gas in Ethiopia (in what is more often considered to be the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

), and very rare occurrences in Europe (for example some mustard gas bombs were dropped on Warsaw on 3 September 1939, which Germany acknowledged in 1942 but indicated had been accidental). Mustard gas was the agent of choice, with the British stockpiling 40,719 tons, the Soviets 77,400 tons, the Americans over 87,000 tons and the Germans 27,597 tons. The destruction of an American cargo ship containing mustard gas led to many casualties in Bari, Italy, in December 1943.

In both Axis and Allied nations, children in school were taught to wear gas masks in case of gas attack. Germany developed the poison gases tabun, sarin, and soman

Soman (or GD, EA 1210, Zoman, PFMP, A-255, systematic name: ''O''-pinacolyl methylphosphonofluoridate) is an extremely toxic chemical substance. It is a nerve agent, interfering with normal functioning of the mammalian nervous system by inhibiti ...

during the war, and used Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

in their extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s. Neither Germany nor the Allied nations used any of their war gases in combat, despite maintaining large stockpiles and occasional calls for their use.The US reportedly had about 135,000 tons of chemical warfare agents during WW II; Germany had 70,000 tons, Britain 40,000 and Japan 7,500 tons. The German nerve gas

Nerve agents, sometimes also called nerve gases, are a class of organic chemicals that disrupt the mechanisms by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by the blocking of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that ...

es were deadlier than the old-style suffocants (chlorine, phosgene) and blistering agents (mustard gas) in Allied stockpiles. Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

, and several American generals reportedly called for their use against Germany and Japan, respectively (Weber, 1985). Poison gas played an important role in the Holocaust.

Britain made plans to use mustard gas on the landing beaches in the event of an invasion of the United Kingdom in 1940. The United States considered using gas to support their planned invasion of Japan.

Casualties

The contribution of gas weapons to the total casualty figures was relatively minor. British figures, which were accurately maintained from 1916, recorded that 3% of gas casualties were fatal, 2% were permanently invalid and 70% were fit for duty again within six weeks. Death by gas was often slow and painful. According to Denis Winter (''Death's Men'', 1978), a fatal dose of phosgene eventually led to "shallow breathing and retching, pulse up to 120, an ashen face and the discharge of four pints (2 litres) of yellow liquid from the lungs each hour for the 48 of the drowning spasms."

A common fate of those exposed to gas was blindness, chlorine gas or mustard gas being the main causes. One of the most famous First World War paintings, '' Gassed'' by John Singer Sargent, captures such a scene of mustard gas casualties which he witnessed at a dressing station at Le Bac-du-Sud near Arras in July 1918. (The gases used during that battle (tear gas) caused temporary blindness and/or a painful stinging in the eyes. These bandages were normally water-soaked to provide a rudimentary form of pain relief to the eyes of casualties before they reached more organized medical help.)

The proportion of mustard gas fatalities to total casualties was low; 2% of mustard gas casualties died and many of these succumbed to secondary infections rather than the gas itself. Once it was introduced at the

Death by gas was often slow and painful. According to Denis Winter (''Death's Men'', 1978), a fatal dose of phosgene eventually led to "shallow breathing and retching, pulse up to 120, an ashen face and the discharge of four pints (2 litres) of yellow liquid from the lungs each hour for the 48 of the drowning spasms."

A common fate of those exposed to gas was blindness, chlorine gas or mustard gas being the main causes. One of the most famous First World War paintings, '' Gassed'' by John Singer Sargent, captures such a scene of mustard gas casualties which he witnessed at a dressing station at Le Bac-du-Sud near Arras in July 1918. (The gases used during that battle (tear gas) caused temporary blindness and/or a painful stinging in the eyes. These bandages were normally water-soaked to provide a rudimentary form of pain relief to the eyes of casualties before they reached more organized medical help.)

The proportion of mustard gas fatalities to total casualties was low; 2% of mustard gas casualties died and many of these succumbed to secondary infections rather than the gas itself. Once it was introduced at the third battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

, mustard gas produced 90% of all British gas casualties and 14% of battle casualties of any type.

Mustard gas was a source of extreme dread. In ''The Anatomy of Courage'' (1945), Lord Moran, who had been a medical officer during the war, wrote:

Mustard gas did not need to be inhaled to be effective—any contact with skin was sufficient. Exposure to 0.1 ppm was enough to cause massive blisters. Higher concentrations could burn flesh to the bone. It was particularly effective against the soft skin of the eyes, nose, armpits and groin, since it dissolved in the natural moisture of those areas. Typical exposure would result in swelling of the conjunctiva

The conjunctiva is a thin mucous membrane that lines the inside of the eyelids and covers the sclera (the white of the eye). It is composed of non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium with goblet cells, stratified columnar epithelium ...

and eyelids, forcing them closed and rendering the victim temporarily blind. Where it contacted the skin, moist red patches would immediately appear which after 24 hours would have formed into blisters. Other symptoms included severe headache, elevated pulse and temperature (fever), and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

(from blistering in the lungs).

Many of those who survived a gas attack were scarred for life. Respiratory disease and failing eyesight were common post-war afflictions. Of the Canadians who, without any effective protection, had withstood the first chlorine attacks during Second Ypres, 60% of the casualties had to be repatriated and half of these were still unfit by the end of the war, over three years later.

Many of those who were fairly soon recorded as fit for service were left with scar tissue in their lungs. This tissue was susceptible to tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...