Pincer attack on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

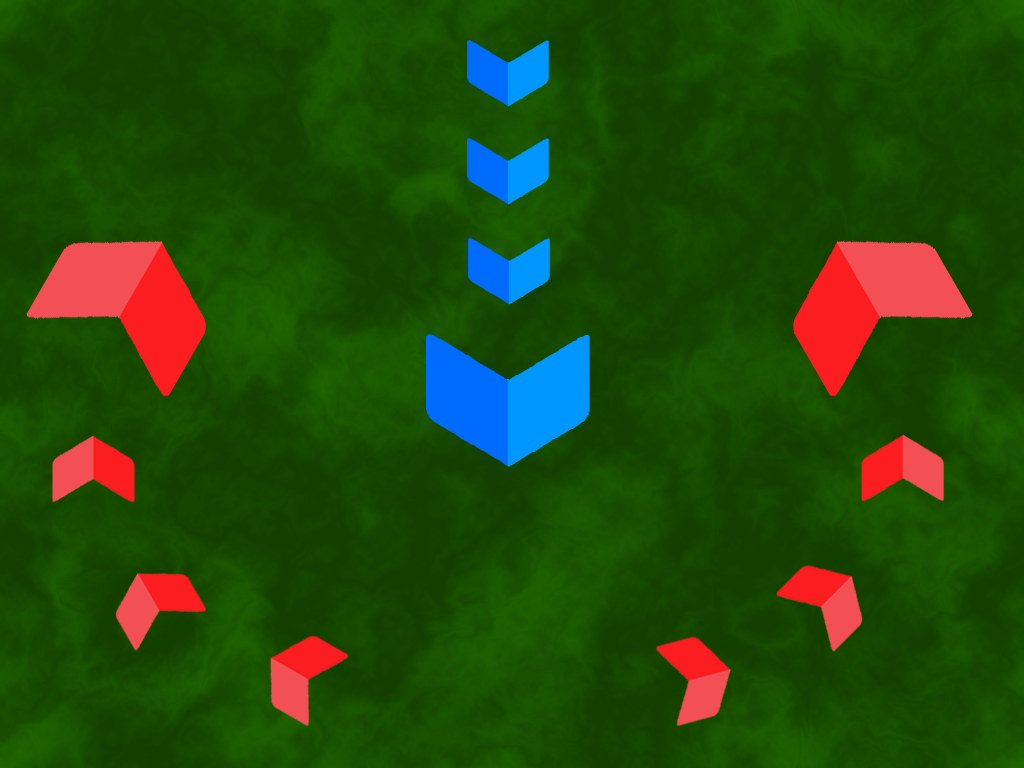

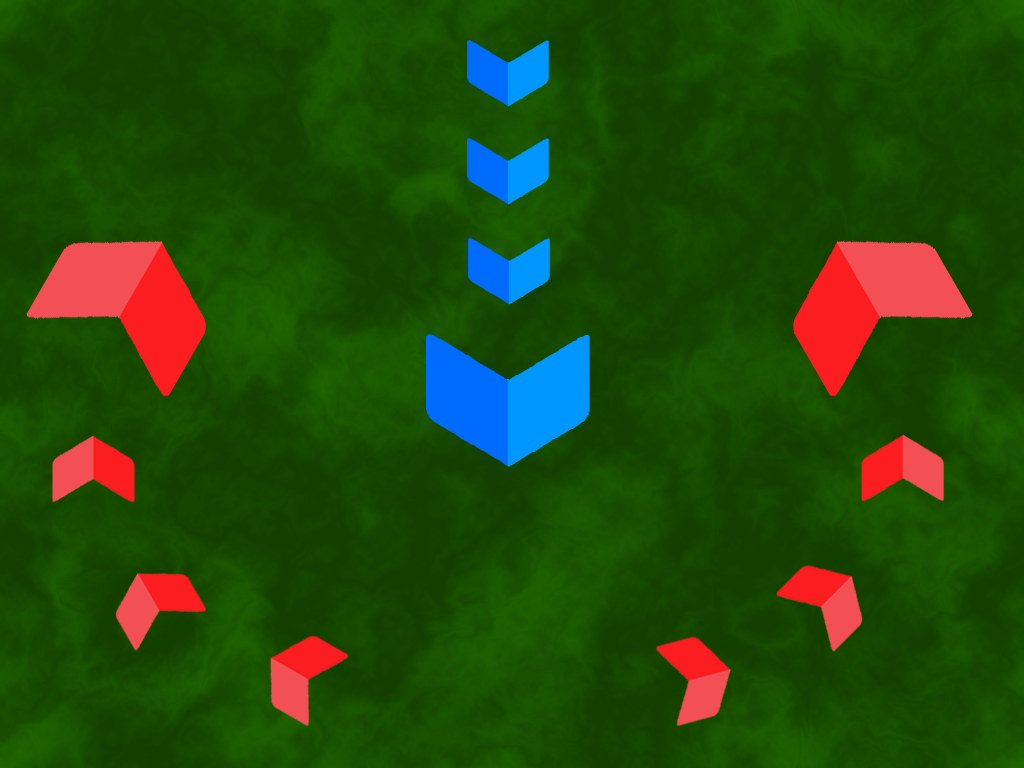

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver holds an important foothold throughout the history of warfare.

The pincer movement typically occurs when opposing forces advance towards the center of an army that responds by moving its outside forces to the enemy's flanks to surround it. At the same time, a second layer of pincers may attack the more distant flanks to keep reinforcements from the target units.

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver holds an important foothold throughout the history of warfare.

The pincer movement typically occurs when opposing forces advance towards the center of an army that responds by moving its outside forces to the enemy's flanks to surround it. At the same time, a second layer of pincers may attack the more distant flanks to keep reinforcements from the target units.

diagram

of different modes of attack, including double envelopment. *GlobalSecurity.or

with a section on envelopments. *Academi

paper

on military diagramming with diagram of a double envelopment.

Map

of

Description

A full pincer movement leads to the attacking army facing the enemy in front, on both flanks, and in the rear. If attacking pincers link up in the enemy's rear, the enemy is encircled. Such battles often end in surrendering or destroying the enemy force, but the encircled force can try to break out. They can attack the encirclement from the inside to escape, or a friendly external force can attack from the outside to open an escape route.History

Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu ( ; zh, t=孫子, s=孙子, first= t, p=Sūnzǐ) was a Chinese military general, strategist, philosopher, and writer who lived during the Eastern Zhou period of 771 to 256 BCE. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of '' The ...

, in ''The Art of War

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is com ...

'' (traditionally dated to the 6th century BC), speculated on the maneuver but advised against trying it for fear that an army would likely run first before the move could be completed. He argued that it was best to allow the enemy a path to escape (or at least the appearance of one), as the target army would fight with more ferocity when surrounded. Still, it would lose formation and be more vulnerable to destruction if shown an avenue of escape.

The maneuver may have first been used at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. The battle was the culmination o ...

in 490 BC. The historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

describes how the Athenian general Miltiades

Miltiades (; grc-gre, Μιλτιάδης; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian citizen known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon ...

deployed 900 Plataean and 10,000 Athenian hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The f ...

in a U-formation with the wings manned much more deeply than the center. His enemy outnumbered him heavily, and Miltiades chose to match the breadth of the Persian battle line by thinning out the center of his forces while reinforcing the wings. In the course of the battle, the weaker central formations retreated, allowing the wings to converge behind the Persian battle line and drive the more numerous but lightly armed Persians to retreat in panic.

The maneuver was used by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

at the Battle of the Hydaspes

The Battle of the Hydaspes was fought between Alexander the Great and king Porus in 326 BC. It took place on the banks of the Jhelum River (known to the ancient Greeks as Hydaspes) in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent (modern-day ...

in 326 BC. He launched his attack at the Indian left flank, and the Indian king Porus

Porus or Poros ( grc, Πῶρος ; 326–321 BC) was an ancient Indian king whose territory spanned the region between the Jhelum River (Hydaspes) and Chenab River (Acesines), in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. He is only ment ...

reacted by sending the cavalry on the right of his formation around in support. Alexander had positioned two cavalry units on the left of his formation, hidden from view, under the command of Coenus and Demitrius. The units were then able to follow Porus's cavalry around, trapping them in a classic pincer movement.

The most famous example of its use was at the Battle of Cannae

The Battle of Cannae () was a key engagement of the Second Punic War between the Roman Republic and Carthage, fought on 2 August 216 BC near the ancient village of Cannae in Apulia, southeast Italy. The Carthaginians and their allies, led by Ha ...

in 216 BC, when Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Pu ...

executed the maneuver against the Romans. Military historians cite it as the first successful use of the pincer movement that was recorded in detail, by the Greek historian Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

.

It was also later used by Khalid ibn al-Walid

Khalid ibn al-Walid ibn al-Mughira al-Makhzumi (; died 642) was a 7th-century Arab military commander. He initially headed campaigns against Muhammad on behalf of the Quraysh. He later became a Muslim and spent the remainder of his career in ...

at the Battle of Walaja

The Battle of Walaja ( ar, معركة الولجة) was a battle fought in Mesopotamia (Iraq) in May 633 between the Rashidun Caliphate army under Khalid ibn al-Walid and Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha against the Sassanid Empire and its Arab allies. ...

in 633, by Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan was the second Sultan of the Seljuk Empire and great-grandson of Seljuk, the eponymous founder of the dynasty. He greatly expanded the Seljuk territory and consolidated his power, defeating rivals to the south and northwest, and his ...

at the Battle of Manzikert

The Battle of Manzikert or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, theme of Iberia (modern Malazgirt in Muş Province, Turkey). The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army and ...

in 1071 (under the name ''crescent tactic'') and by Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

at the Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of ...

in 1187.

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; ; xng, Temüjin, script=Latn; ., name=Temujin – August 25, 1227) was the founder and first Great Khan (Emperor) of the Mongol Empire, which became the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in history a ...

used a rudimentary form known colloquially as the ''horns'' tactic. Two enveloping flanks of horsemen surrounded the enemy, but they usually remained unjoined, leaving the enemy an escape route to the rear. It was key to many of Genghis's early victories over other Mongolian tribes.

It was used at the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

by Süleyman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

in 1526 and by Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld

Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld (6 August 1651 – 29 January 1722) was a Swedish Field Marshal ('' Fältmarskalk'') and Royal Councillor. He was mentor and chief military advisor to King Charles XII of Sweden, and served as deputy commander- ...

at the Battle of Fraustadt

The Battle of Fraustadt was fought on 2 February 1706 ( O.S.) / 3 February 1706 (Swedish calendar) / 13 February 1706 ( N.S.) between Sweden and Saxony-Poland and their Russian allies near Fraustadt (now Wschowa) in Poland. During the Battle of F ...

in 1706.

Even in the horse-and-musket era, the maneuver was used across many military cultures. A double envelopment was deployed by the Iranian conqueror Nader Shah

Nader Shah Afshar ( fa, نادر شاه افشار; also known as ''Nader Qoli Beyg'' or ''Tahmāsp Qoli Khan'' ) (August 1688 – 19 June 1747) was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran and one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian ...

at the Battle of Kirkuk (1733)

The Battle of Kirkuk (Persian: نبرد کرکوک), also known as the Battle of Agh-Darband (Persian: نبرد آقدربند), was the last battle in Nader Shah's Mesopotamian campaign where he avenged his earlier defeat at the hands ...

against the Ottomans; the Persian army, under Nader, flanked the Ottomans on both ends of their line and encircled their centre despite being numerically at a disadvantage. In another battle at Kars in 1745, Nader routed the Ottoman army and subsequently encircled their encampment. The Ottoman army soon after collapsed under the pressure of the encirclement. Also during the Battle of Karnal

The Battle of Karnal (24 February 1739), was a decisive victory for Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran, during his invasion of India. Nader's forces defeated the army of Muhammad Shah within three hours, paving the way fo ...

in 1739, Nader drew out the Mughal army which outnumbered his own force by over six to one, and managed to encircle and defeat a significant contingent of the Mughals in an ambush around Kunjpura village.

Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan (1735–1736July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. One of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783, he later commanded troops during the sup ...

used it at the Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was an engagement during the American Revolutionary War fought on January 17, 1781 near the town of Cowpens, South Carolina, between U.S. forces under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan and Kingdom of Great Britain, British for ...

in 1781 in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. Zulu impi

is a Zulu word meaning war or combat and by association any body of men gathered for war, for example is a term denoting an army. were formed from regiments () from (large militarised homesteads). In English is often used to refer to a ...

s used a version of the maneuver that they called the ''buffalo horn'' formation.

The maneuver was used in the blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air ...

of the armed forces of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, developing into a complex, multidisciplinary endeavor. It involved fast movement by mechanized armor, artillery barrages, air force bombardment, and effective radio communications, with the primary objective of destroying enemy command and control

Command and control (abbr. C2) is a "set of organizational and technical attributes and processes ...

chains, undermining enemy troop morale and disrupting supply lines. During the hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

employs human, physical, and information resources to solve problems and accomplish missions" to achieve the goals of an organization o ...Battle of Kiev (1941)

The First Battle of Kiev was the German name for the operation that resulted in a huge encirclement of Soviet troops in the vicinity of Kiev during World War II. This encirclement is considered the largest encirclement in the history of warfar ...

the Axis forces managed to encircle the largest number of soldiers in the history of warfare. Well over half-a-million Soviet soldiers were taken prisoner by the end of the operation.

See also

*Encirclement

Encirclement is a military term for the situation when a force or target is isolated and surrounded by enemy forces. The situation is highly dangerous for the encircled force. At the strategic level, it cannot receive supplies or reinforcemen ...

* Flanking maneuver

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver is a movement of an armed force around an enemy force's side, or flank, to achieve an advantageous position over it. Flanking is useful because a force's fighting strength is typically concentrated i ...

* Two-front war

According to military terminology, a two-front war occurs when opposing forces encounter on two geographically separate fronts. The forces of two or more allied parties usually simultaneously engage an opponent in order to increase their chance ...

References

Further reading

*U.S. Army training manuadiagram

of different modes of attack, including double envelopment. *GlobalSecurity.or

with a section on envelopments. *Academi

paper

on military diagramming with diagram of a double envelopment.

Map

of

Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

's double envelopment at the battle of Stalingrad.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pincer Movement

Maneuver tactics

Military strategy