Phillips Academy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

("Not for Self")

la, Finis Origine Pendet

("The End Depends Upon the Beginning")

Youth From Every Quarter

Knowledge and Goodness , address = 180 Main Street , city =

1973 – merged with

$44,800 (day) , colors = Navy

White , affiliations = Eight Schools Association

Ten Schools Admissions Organization , homepage = , accreditation = NAIS

TABS , founder = Samuel Phillips Jr. , free_label_1 = Former pupils , free_1 = Old Phillipians Phillips Academy (also known as PA, Phillips Academy Andover, or simply Andover) is a

Phillips Academy was founded during the

Phillips Academy was founded during the  Several figures from the revolutionary period are associated with the school.

Several figures from the revolutionary period are associated with the school.  Phillips Academy curriculum and extracurricular activities include music ensembles, 30 competitive sports, a campus newspaper, a radio station, and a debate club. In 1973 Phillips Academy merged with neighboring

Phillips Academy curriculum and extracurricular activities include music ensembles, 30 competitive sports, a campus newspaper, a radio station, and a debate club. In 1973 Phillips Academy merged with neighboring

* Graham House was formerly used by both the school's psychology department and the school's psychological counselors. The psychology department has since moved to the Rebecca M. Sykes Wellness Center.

* Graham House was formerly used by both the school's psychology department and the school's psychological counselors. The psychology department has since moved to the Rebecca M. Sykes Wellness Center.

* Graves Hall is used by the music department. Built in 1882, it was named after Professor William Blair Graves and was originally a chemical laboratory. The building houses a rehearsal space (Pfatteicher Room), a concert hall (Timken Hall), an electronic music studio, and several classrooms and practice rooms.

* Morse Hall is used by the Math Department, CAMD (Community and Multicultural Development), the student-run radio station ( WPAA), and some of the student-run publications. Morse Hall is named after

* Graves Hall is used by the music department. Built in 1882, it was named after Professor William Blair Graves and was originally a chemical laboratory. The building houses a rehearsal space (Pfatteicher Room), a concert hall (Timken Hall), an electronic music studio, and several classrooms and practice rooms.

* Morse Hall is used by the Math Department, CAMD (Community and Multicultural Development), the student-run radio station ( WPAA), and some of the student-run publications. Morse Hall is named after

The school also has dormitories to house the roughly 800 students that board. These buildings range in size from housing as few as four to as many as 40 students. The campus is organized into five "clusters," groups of dorms situated closely together. These five clusters are named Abbot, Flagstaff, Pine Knoll, West Quad North, and West Quad South. Each cluster contains around 220 students, 40 faculty families, and a cluster dean and are responsible for organizing social events, orientation, study breaks, and munches (cluster-wide snacking social events).

Two notable dorms are America House, where the song ''

The school also has dormitories to house the roughly 800 students that board. These buildings range in size from housing as few as four to as many as 40 students. The campus is organized into five "clusters," groups of dorms situated closely together. These five clusters are named Abbot, Flagstaff, Pine Knoll, West Quad North, and West Quad South. Each cluster contains around 220 students, 40 faculty families, and a cluster dean and are responsible for organizing social events, orientation, study breaks, and munches (cluster-wide snacking social events).

Two notable dorms are America House, where the song ''

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum given to the school by alumnus Thomas Cochran in memory of his friend Keturah Addison Cobb. Its permanent collection includes

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum given to the school by alumnus Thomas Cochran in memory of his friend Keturah Addison Cobb. Its permanent collection includes

As a way to encourage all students to try new things and stay healthy, all students are required to have an athletic commitment each term. A range of instructional sports are available for those who wish to try new things, and for those already established in a sport, most teams have at least a varsity and junior varsity squad.

As a way to encourage all students to try new things and stay healthy, all students are required to have an athletic commitment each term. A range of instructional sports are available for those who wish to try new things, and for those already established in a sport, most teams have at least a varsity and junior varsity squad.

File:George_H._W._Bush_presidential_portrait_(cropped).jpg, President George H. W. Bush

File:George-W-Bush.jpeg, President George W. Bush

File:Josiah Quincy 1772-1864.jpg,

Andover has educated two American presidents ( George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush), a

"The WASP ascendancy"

, "...In 1930, eight private schools accounted for nearly one-third of Yale freshman: Andover (74), Exeter (54), Hotchkiss (42), St. Paul's (24), Choate (19), Lawrenceville (19), Hill (17) and Kent (14) ...". Accessed June 26, 2013. An account in ''

"What Is It Like to Attend a Top Boarding School?"

. Accessed June 24, 2013. She elaborated that Andover provided two sign language interpreters, free of charge, to help her academically to cope with her deafness. While the overall image may be changing to one which emphasizes greater diversity and respect for individual talent, the image of the school in the media continues to connote privilege, money, exclusivity, prestige, academic quality, and sometimes negatively connotes chumminess, clubbiness, or arrogance. The school is often mentioned in books and film, and on television. Some examples include: * In Chapter 17 of ''

Phillips Academy Andover on Instagram

archived fro

the original

{{DEFAULTSORT:Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts 1778 establishments in Massachusetts Boarding schools in Massachusetts Buildings and structures in Andover, Massachusetts Co-educational boarding schools Educational institutions established in 1778 Phillips family (New England) Private high schools in Massachusetts Private preparatory schools in Massachusetts Schools in Essex County, Massachusetts Six Schools League

("Not for Self")

la, Finis Origine Pendet

("The End Depends Upon the Beginning")

Youth From Every Quarter

Knowledge and Goodness , address = 180 Main Street , city =

Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

, state = Massachusetts

, zipcode = 01810

, country = United States

, coordinates =

, pushpin_map = Massachusetts#USA

, fundingtype = Private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

, schooltype = Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

, College-preparatory

A college-preparatory school (usually shortened to preparatory school or prep school) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to public, private independent or parochial schools primarily designed to prepare students for higher educat ...

, Day

A day is the time period of a full rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours, 1440 minutes, or 86,400 seconds. In everyday life, the word "day" often refers to a solar day, which is the length between two ...

& Boarding

Boarding may refer to:

*Boarding, used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals as in a:

** Boarding house

**Boarding school

*Boarding (horses) (also known as a livery yard, livery stable, or boarding stable), is a stable where ho ...

, established = 1973 – merged with

Abbot Academy

Abbot Academy (also known as Abbot Female Seminary and AA) was an independent boarding preparatory school for women boarding and day students in grades 9–12 from 1828 to 1973. Located in Andover, Massachusetts, Abbot Academy was notable as one ...

, ceeb = 220030

, us_nces_school_id = 00603199

, head = Raynard S. Kington

Raynard S. Kington is an American educator and the 16th Head of School of Phillips Academy in Andover."Presidential Transition Announcement," Grinnell College, December 5, 2019, https://www.grinnell.edu/news/presidential-transition-announcement. ...

, president = Peter L.S. Currie

, teaching_staff = 213.6 (2017–18)

, grades = 9– 12, PG

, gender = Coeducation

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

al

, enrollment = 1,131 (2017-18)

, grade9 = 228

, grade10 = 300

, grade11 = 284

, grade12 = 319

, grade13 =

, other_grade_label_1 = Boarding Students

, other_grade_enrollment_1 = 848

, other_grade_label_2 = Day Students

, other_grade_enrollment_2 = 282

, ratio = 5.3:1 (2017–18)

, conference = NEPSAC

The New England Preparatory School Athletic Council (NEPSAC) is an organization that serves as the governing body for Sport, sports in College-preparatory school, preparatory schools and Sports league, leagues in New England. The organization has ...

SSL SSL may refer to:

Entertainment

* RoboCup Small Size League, robotics football competition

* ''Sesame Street Live'', a touring version of the children's television show

* StarCraft II StarLeague, a Korean league in the video game

Natural language ...

, mascot = Gunga, the gorilla

, team_name = Big Blue

, rival = Phillips Exeter Academy

(not for oneself) la, Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) gr, Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God)

, location = 20 Main Street

, city = Exeter, New Hampshire

, zipcode ...

, SAT = 2112

, head_name = Head of School

, campus_type = Suburban

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a larger city/urban area or as a separa ...

, campus_size =

, newspaper = The Phillipian

, yearbook = Pot Pourri

, budget = $138 million (2019)

, endowment = US $1.13 billion (December 2019)

, tuition = $57,800 (boarding)$44,800 (day) , colors = Navy

White , affiliations = Eight Schools Association

G30 Schools

G30 Schools, formerly known as G20 Schools, is an informal association of secondary schools initiated by David Wylde of St. Andrew's College, Grahamstown, South Africa and Anthony Seldon of Wellington College, Berkshire, United Kingdom in 2006.

...

Ten Schools Admissions Organization , homepage = , accreditation = NAIS

TABS , founder = Samuel Phillips Jr. , free_label_1 = Former pupils , free_1 = Old Phillipians Phillips Academy (also known as PA, Phillips Academy Andover, or simply Andover) is a

co-educational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

university-preparatory school

A college-preparatory school (usually shortened to preparatory school or prep school) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to public, private independent or parochial schools primarily designed to prepare students for higher educatio ...

for boarding

Boarding may refer to:

*Boarding, used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals as in a:

** Boarding house

**Boarding school

*Boarding (horses) (also known as a livery yard, livery stable, or boarding stable), is a stable where ho ...

and day

A day is the time period of a full rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours, 1440 minutes, or 86,400 seconds. In everyday life, the word "day" often refers to a solar day, which is the length between two ...

students in grades 9–12, along with a post-graduate year. The school is in Andover, Massachusetts

Andover is a town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. It was settled in 1642 and incorporated in 1646."Andover" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th ed., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 387. As of th ...

, United States, 25 miles north of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. Phillips Academy has 1,131 students, and is a highly selective school

A selective school is a school that admits students on the basis of some sort of selection criteria, usually academic. The term may have different connotations in different systems and is the opposite of a comprehensive school, which accepts all s ...

, accepting 13% of applicants with a yield as high as 86% (in 2017). It is part of the Eight Schools Association and the Ten Schools Admissions Organization, as well as the G30 Schools Group.

Founded in 1778, Andover is one of the oldest incorporated secondary school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

s in the United States. It has educated a long list of notable alumni through its history, including American presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush, foreign heads of state, numerous members of Congress, five Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make ou ...

and six Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

recipients. It has been referred to by many contemporary sources as the most elite boarding school in America.

It became coeducational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to ...

in 1973, the year in which it merged with its neighbor girls' school Abbot Academy

Abbot Academy (also known as Abbot Female Seminary and AA) was an independent boarding preparatory school for women boarding and day students in grades 9–12 from 1828 to 1973. Located in Andover, Massachusetts, Abbot Academy was notable as one ...

.

Overview

Phillips Academy is the oldest incorporated academy in the United States, established in 1778 by Samuel Phillips Jr. His uncle,Dr. John Phillips

John Phillips (December 27, 1719 – , 1795) was an early American educator and the cofounder of Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, along with his wife, Elizabeth Phillips. He was a major donor to Dartmouth College, where he served ...

, later founded Phillips Exeter Academy

(not for oneself) la, Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) gr, Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God)

, location = 20 Main Street

, city = Exeter, New Hampshire

, zipcode ...

in 1781. Phillips Academy's endowment stood at just over one billion dollars as of February 2016. Andover is subject to the control of a board of trustees, headed by Amy Falls, who succeeded Peter Currie, business executive and former Netscape

Netscape Communications Corporation (originally Mosaic Communications Corporation) was an American independent computer services company with headquarters in Mountain View, California and then Dulles, Virginia. Its Netscape web browser was on ...

Chief Financial Officer

The chief financial officer (CFO) is an officer of a company or organization that is assigned the primary responsibility for managing the company's finances, including financial planning, management of financial risks, record-keeping, and fina ...

, who himself had taken over as president of the Phillips Academy Board of Trustees on July 1, 2012. On December 5, 2019, Dr. Raynard S. Kington

Raynard S. Kington is an American educator and the 16th Head of School of Phillips Academy in Andover."Presidential Transition Announcement," Grinnell College, December 5, 2019, https://www.grinnell.edu/news/presidential-transition-announcement. ...

, 13th President of Grinnell College

Grinnell College is a private liberal arts college in Grinnell, Iowa, United States. It was founded in 1846 when a group of New England Congregationalists established the Trustees of Iowa College.

Grinnell has the fifth highest endowment-to-stu ...

, was named the 16th Head of School.

Phillips Academy admitted only boys until the school became coeducational in 1973, the year of Phillips Academy's merger with Abbot Academy

Abbot Academy (also known as Abbot Female Seminary and AA) was an independent boarding preparatory school for women boarding and day students in grades 9–12 from 1828 to 1973. Located in Andover, Massachusetts, Abbot Academy was notable as one ...

, a boarding school for girls also in Andover. Abbot Academy, founded in 1828, was one of the first incorporated schools for girls in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. Then-headmaster Theodore Sizer of Phillips and Donald Gordon of Abbot oversaw the merger.

Andover traditionally educated its students for Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, just as Phillips Exeter Academy educated its students for Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, and Lawrenceville prepped students for Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

.

The school's student-run newspaper, '' The Phillipian'', is the oldest secondary school newspaper in the United States, the next oldest secondary school newspaper being ''The Exonian

''The Exonian'' is the bi-weekly student-run newspaper of Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire. It has been printed continuously since April 6, 1878, making it the oldest continuously-published preparatory school newspaper in the count ...

'', Phillips Exeter Academy's weekly. ''The Phillipian'' was first published on July 28, 1857, and has been published regularly since 1878. It retains financial and editorial independence from Phillips Academy, having completed a $500,000 endowment drive in 2014. Students comprise the editorial board and make all decisions for the paper, consulting with two faculty advisors at their own discretion. The Philomathean Society is one of the oldest high school debate societies in the nation, second to the Daniel Webster Debate Society at Phillips Exeter Academy.

Phillips Academy also runs a five-week summer session for approximately 600 students entering grades 8 through 12.

History

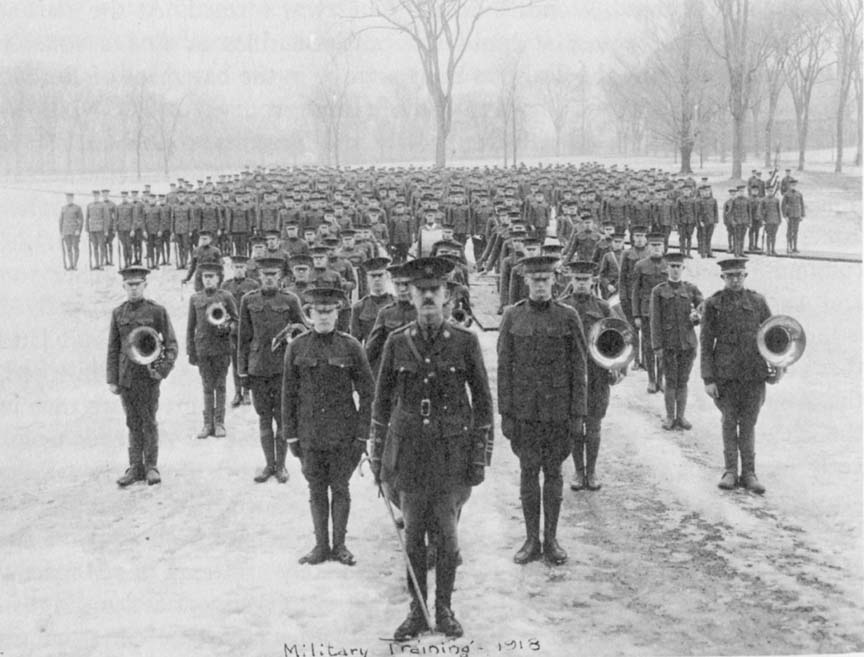

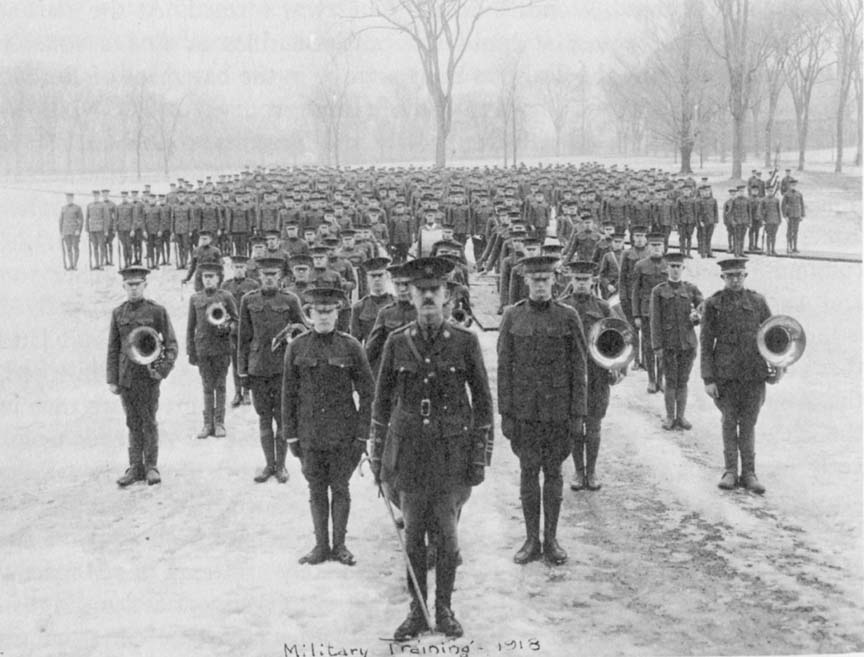

Phillips Academy was founded during the

Phillips Academy was founded during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

as an all-boys school in 1778 by Samuel Phillips Jr.

Phillips Academy's traditional rival is Phillips Exeter Academy

(not for oneself) la, Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) gr, Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God)

, location = 20 Main Street

, city = Exeter, New Hampshire

, zipcode ...

, which was established three years later in Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, by Samuel Phillips' uncle, Dr. John Phillips

John Phillips (December 27, 1719 – , 1795) was an early American educator and the cofounder of Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, along with his wife, Elizabeth Phillips. He was a major donor to Dartmouth College, where he served ...

, who was also a major contributor to Andover's founding. The two schools still maintain a rivalry. The football teams have met nearly every year since 1878, making it the oldest prep school rivalry in the country. In 1882, the first high school lacrosse teams were formed at Phillips Academy, Phillips Exeter Academy and the Lawrenceville School.

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

visited the school during his presidency in 1789, and Washington's nephews later attended the school. John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor o ...

signed the school's articles of incorporation and the great seal of the school was designed by Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

.

For a hundred years of its history, Phillips Academy shared its campus with the Andover Theological Seminary

Andover Theological Seminary (1807–1965) was a Congregationalist seminary founded in 1807 and originally located in Andover, Massachusetts on the campus of Phillips Academy. From 1908 to 1931, it was located at Harvard University in Cambridge. ...

, which was founded on Phillips Hill in 1807 by orthodox Calvinists

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John ...

who had fled Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

after it appointed a liberal Unitarian theologian to a professorship of divinity. The Andover Theological Seminary was independent of Phillips Academy but shared the same board of directors. In 1908, the seminary departed Phillips Academy, leaving behind its key buildings: academic building Pearson Hall (formerly a chapel), and dormitories Foxcroft Hall and Bartlet Hall. These buildings later became part of the Andover campus, which was expanded in the 1920s and 1930s around this historic core with new buildings of similar Georgian style: Samuel Phillips Hall, George Washington Hall, Samuel Morse Hall, Paul Revere Hall, Oliver Wendell Holmes Library, Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons c ...

, the Addison Gallery of American Art

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an academic museum dedicated to collecting American art, organized as a department of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.

History

Directors of the gallery include Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr. (1940– ...

and Cochran Chapel. Small portions of Andover's campus were laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co- ...

, designer of Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated ...

and himself a graduate of the school.

Revere's design of the school's seal incorporated bees, a beehive, and the sun. The school's primary motto, ''Non Sibi'', located in the sun, means "not for oneself". The school's second motto, ''Finis Origine Pendet'', meaning "the end depends upon the beginning", is scrolled across the bottom of the seal.

Phillips was one of the schools where students on the Chinese Educational Mission were sent to study by the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

government from 1878 to 1881. One of the students, Liang Cheng

Liang Cheng (November 30, 1864 – February 3, 1917), courtesy name Liang Chentung, also known as Liang Pi Yuk, and later as Chentung Liang Cheng, was a Chinese ambassador to the United States during the Qing dynasty. He was primarily respon ...

, later became the Chinese ambassador to the United States.

During the 1930s the school was involved in the International Schoolboy Fellowship, a cultural exchange program between US academies, British public schools and Nazi boarding schools.

Phillips Academy curriculum and extracurricular activities include music ensembles, 30 competitive sports, a campus newspaper, a radio station, and a debate club. In 1973 Phillips Academy merged with neighboring

Phillips Academy curriculum and extracurricular activities include music ensembles, 30 competitive sports, a campus newspaper, a radio station, and a debate club. In 1973 Phillips Academy merged with neighboring Abbot Academy

Abbot Academy (also known as Abbot Female Seminary and AA) was an independent boarding preparatory school for women boarding and day students in grades 9–12 from 1828 to 1973. Located in Andover, Massachusetts, Abbot Academy was notable as one ...

, which was founded in 1829 as one of the first schools for girls in New England and named for Sarah Abbot. After existing at Phillips Academy almost since its inception, secret societies

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ...

were officially disbanded in 1949. Despite this, at least one secret society continues to exist.

Phillips Academy is one of only a few private high schools (others include Roxbury Latin and St. Andrew's School) in the United States that attained need-blind admissions in 2007 and 2008, and it has continued this policy through the present. In 2013 it received 3,029 applications and accepted 13%, a record low acceptance rate for the school. Of those accepted, 79% went on to matriculate at the Academy.

Academics

Phillips Academy follows atrimester program

An academic term (or simply term) is a portion of an academic year, the time during which an educational institution holds classes. The schedules adopted vary widely.

In most countries, the academic year begins in late summer or early autumn an ...

, where a school year is divided into three terms, with each term lasting approximately 10 weeks. Classes are held from Monday to Friday, with the first period of the day beginning at 8:30 am and the last period ending at 2:50 pm. On Wednesdays, classes end early at 1:00 pm in order to provide more time for athletics, clubs, and community service.

Many courses are year-long, while others last only one to two terms. Most students take five courses each trimester. Four-year students at Phillips Academy are required to take courses in English, foreign language, mathematics (through precalculus), history and social science, laboratory science, art, music, philosophy and religious studies, and physical education. Students may also choose to pursue an independent research program in a topic of choice under the guidance of faculty members if there are no more courses suitable for them in one or more disciplines.

Andover does not rank students, and rather than a four-point GPA scale, Phillips Academy calculates GPA using a six-point system. The Office of the Dean of Studies claims that there is no formal equivalent between the zero-to-six system and a conventional letter-grade system. However, a six is considered outstanding and is (theoretically) rarely awarded, a five is the lowest honors grade, and a two is the lowest passing grade. Grades earned in classes are sometimes weighted at the discretion of the instructor, and the school provides no uniform scale for converting percent scores into grades on the six-point scale.

For the 239 members of the class of 2018, average SAT scores were 720 on the English section and 740 on the Math section.

Facilities

Academic facilities

* Bulfinch Hall was designed by Asher Benjamin, a student of architectCharles Bulfinch

Charles Bulfinch (August 8, 1763 – April 15, 1844) was an early American architect, and has been regarded by many as the first American-born professional architect to practice.Baltzell, Edward Digby. ''Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia''. Tran ...

, and built in 1819. It now houses the English Department and received renovations during the summer and fall term of 2012.

* The Gelb Science Center, named after alumnus donor Richard L. Gelb, opened for classes in January 2004. It replaced the older Evans Hall which was built in 1963 and demolished following the completion of Gelb. Gelb has three floors, each devoted to a separate science. The first floor houses biology, the second floor physics, and the third floor chemistry. Gelb also has an observatory above the third floor. Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

, who graduated from Phillips Academy in 1805 and later invented the telegraph and Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

.

* Oliver Wendell Holmes Library (OWHL) was built in 1929 (renovated 1987 and 2018–2019) and is named after Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., an 1825 graduate of Phillips Academy. The library's construction was funded by Thomas Cochran and Louis Cochran Savage in the names of their brothers William, Class of 1895, and Montcreiff, Class of 1900, costing around $500,000. It is built in the Georgian Revival architectural style. The hip roof contains a skylight to bring natural light into the interior spaces.The library houses more than 120,000 works. Located in OWHL is the Garver Room, known to students as "Silent Study." The Garver Room containing the most comprehensive secondary-school reference collection in the country. In 2019, the OWHL received the Internet Archive's "Hero Award" for its work on digitizing its book collection and making it available via controlled digital lending

Controlled digital lending (CDL) is a model by which libraries digitize materials in their collection and make them available for lending. It is based on interpretations of the United States copyright principles of fair use and copyright exhaus ...

(i.e. providing digital copies to one user at a time). The 2018-2019 renovations also saw the doubling in size of the school's makerspace (dubbed "The Nest"). The updated facility houses a data lab, two laser cutters, four Makerbot 3-D printers, two resin printers, and a room for robotics groups. Over 50 classes make use of The Nest as a teaching facility.

* Pearson Hall, one of the oldest structures on campus, is the classics building. Built in 1817, it once was the main building of the Andover Theological Seminary. The only subjects with classes that meet in Pearson are Latin, Greek, Greek literature, mythology, and etymology. It was named after the school's first headmaster, Eliphalet Pearson.

* Samuel Phillips Hall was built in 1924 and named after the founder of the school. This building houses the languages, history, and social sciences departments, as well as the school's language lab.

Student facilities

* Cochran Chapel is a neo-Georgian church located on the north side of campus. It is also home to the philosophy, religious studies, and community service departments. A biweekly All School Meeting is held here on Fridays. * Paresky Commons is the school's dining hall. The basement of Commons also houses "Susie's" (originally the Riley Room, and later "the den" until spring 2012), a grill-style student hangout/convenience store. * George Washington Hall was built in 1926 and has since undergone many additions and renovations. The building serves numerous functions, including as an administration building (Head of School's office, dean of studies, dean of students, among others), a post-office (a mail-room), and the Day Student Lounge and locker area. The hall also houses the drama and arts departments. * The Log Cabin is located in the Cochran Wildlife Sanctuary on the northeastern edge of campus and serves as a place for student groups to hold meetings as well as sleep-overs. * Rebecca M. Sykes Wellness Center houses both physical and mental health facilities for students. * The Snyder Center is a 98,000 square-foot space, housing athletic facilities for students, including squash courts and an indoor track. * The Pan Athletic Center is a 70,000 square-foot athletic facility for students, including a swimming and diving complex and dance studios.America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

'' was penned, and Stowe House, where American writer Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel '' Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the har ...

(author of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'') lived while her husband taught at the Andover Theological Seminary

Andover Theological Seminary (1807–1965) was a Congregationalist seminary founded in 1807 and originally located in Andover, Massachusetts on the campus of Phillips Academy. From 1908 to 1931, it was located at Harvard University in Cambridge. ...

. None of the original buildings remain; the oldest dorm is Blanchard House, built in 1789. Several dorms are named after prominent alumni, such as Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, Secretary of War during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and men instrumental in the founding of the Academy, such as Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured ...

and Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

. Also located on campus is The Andover Inn. Built in 1930, The Andover Inn is a New England country inn with 30 rooms and meeting space.

Museums

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum given to the school by alumnus Thomas Cochran in memory of his friend Keturah Addison Cobb. Its permanent collection includes

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum given to the school by alumnus Thomas Cochran in memory of his friend Keturah Addison Cobb. Its permanent collection includes Winslow Homer

Winslow Homer (February 24, 1836 – September 29, 1910) was an American landscape painter and illustrator, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19th-century America and a preeminent figure in ...

's ''Eight Bells'', along with work by John Singleton Copley

John Singleton Copley (July 3, 1738 – September 9, 1815) was an Anglo-American painter, active in both colonial America and England. He was probably born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Richard and Mary Singleton Copley, both Anglo-Irish. Afte ...

, Benjamin West

Benjamin West, (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as '' The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the '' Treaty of Paris'', and '' Benjamin Franklin Drawin ...

, Thomas Eakins

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (; July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was an American realist painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important American artists.

For the length ...

, James McNeill Whistler

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (; July 10, 1834July 17, 1903) was an American painter active during the American Gilded Age and based primarily in the United Kingdom. He eschewed sentimentality and moral allusion in painting and was a leading pr ...

, Frederic Remington

Frederic Sackrider Remington (October 4, 1861 – December 26, 1909) was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in the genre of Western American Art. His works are known for depicting the Western United Sta ...

, George Bellows

George Wesley Bellows (August 12 or August 19, 1882 – January 8, 1925) was an American realist painter, known for his bold depictions of urban life in New York City. He became, according to the Columbus Museum of Art, "the most acclaimed Ame ...

, Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was an American realist painter and printmaker. While he is widely known for his oil paintings, he was equally proficient as a watercolorist and printmaker in etching.

Hopper created subdued drama ...

, Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (November 15, 1887 – March 6, 1986) was an American modernist artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O'Keeffe has been called the "Mother of Ame ...

, Jackson Pollock

Paul Jackson Pollock (; January 28, 1912August 11, 1956) was an American painter and a major figure in the abstract expressionism, abstract expressionist movement. He was widely noticed for his "Drip painting, drip technique" of pouring or splas ...

, Frank Stella

Frank Philip Stella (born May 12, 1936) is an American painter, sculptor and printmaker, noted for his work in the areas of minimalism and post-painterly abstraction. Stella lives and works in New York City.

Biography

Frank Stella was born in Ma ...

, and Andrew Wyeth

Andrew Newell Wyeth ( ; July 12, 1917 – January 16, 2009) was an American visual artist, primarily a realist painter, working predominantly in a regionalist style. He was one of the best-known U.S. artists of the middle 20th century.

In his ...

. The museum also features collections in American photography and decorative arts, with silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

and furniture

Furniture refers to movable objects intended to support various human activities such as seating (e.g., stools, chairs, and sofas), eating ( tables), storing items, eating and/or working with an item, and sleeping (e.g., beds and hammocks) ...

dating back to precolonial America, and a collection of colonial model ships. A rotating schedule of exhibitions is open to students and the public alike. In the spring of 2006, the Phillips Academy Board of Trustees approved a $30-million campaign to renovate and expand the Addison Gallery. Construction on the Addison began in the middle of 2008 and, as of September 7, 2010, is complete, and the museum is once again open to the Phillips Academy community and the broader community of the town of Andover.

The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology was founded in 1901 and is now "one of the nation's major repositories of Native American archaeological collections". The collection includes materials from the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest, Mexico and the Arctic, and range from Paleo Indian (more than 10,000 years ago) to the present day. Since the early 1990s, the museum has been at the forefront of compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law enacted on November 16, 1990.

The Act requires federal agencies and institutions tha ...

. It currently serves as an educational museum for the students of Phillips Academy, but is also accessible to researchers, public schools, and visitors by appointment.

Athletics

History

Athletic competition has long been a part of the Phillips Academy tradition. As early as 1805, football was being played on school grounds, according to a letter that Henry Pearson wrote his father, Eliphalet Pearson in 1805, saying, "I cannot write a long letter as I am very tired after having played at football all this afternoon." The first ever interscholastic football game between high schools was in 1875, when Phillips Academy played against Adams Academy. One of the oldest schoolboy rivalries in American football is the Andover/Exeter competition, started in 1878. That year, the first Andover/Exeter baseball game took place, and ''The Phillipian'' returned from hiatus, named its first Board and began publishing regularly.Harrison, Fred H., ''Athletics for All: Physical Education and Athletics at Phillips Academy, Andover, 1778–1978'' (Andover, Ma.: 1983) Similar boarding school traditions include the Choate-Deerfield rivalry and Hotchkiss-Taft rivalry. Today, Phillips Academy is an athletic powerhouse among New England private schools. Since the ''Constitution of the Phillips Academy Athletic Association'' was drawn up in 1903 with the objective of "Athletics for All," Andover has established 29 different interscholastic programs, and 44 intramural or instructional programs, includingfencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, ...

, tai chi

Tai chi (), short for Tai chi ch'üan ( zh, s=太极拳, t=太極拳, first=t, p=Tàijíquán, labels=no), sometimes called " shadowboxing", is an internal Chinese martial art practiced for defense training, health benefits and meditation. ...

, figure skating

Figure skating is a sport in which individuals, pairs, or groups perform on figure skates on ice. It was the first winter sport to be included in the Olympic Games, when contested at the 1908 Olympics in London. The Olympic disciplines are me ...

, and yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciou ...

. Andover Athletes have been successful in winning over 110 New England Championships in these different sports over the last three decades alone, and have even had the chance to compete abroad, in such competitions as the Henley Royal Regatta

Henley Royal Regatta (or Henley Regatta, its original name pre-dating Royal patronage) is a rowing event held annually on the River Thames by the town of Henley-on-Thames, England. It was established on 26 March 1839. It differs from the thr ...

in Henley, England, for crew.

The athletic directors of Andover and the other members of the Eight Schools Association (ESA) compose the Eight Schools Athletic Council, which organizes sports events and tournaments among ESA schools. Andover is also a member of the New England Preparatory School Athletic Council

The New England Preparatory School Athletic Council (NEPSAC) is an organization that serves as the governing body for sports in preparatory schools and leagues in New England. The organization has 169 full member schools as well as 24 associate ...

.

As a way to encourage all students to try new things and stay healthy, all students are required to have an athletic commitment each term. A range of instructional sports are available for those who wish to try new things, and for those already established in a sport, most teams have at least a varsity and junior varsity squad.

As a way to encourage all students to try new things and stay healthy, all students are required to have an athletic commitment each term. A range of instructional sports are available for those who wish to try new things, and for those already established in a sport, most teams have at least a varsity and junior varsity squad.

Sports

A variety of sports are offered: Fall athletic offerings *Crew

A crew is a body or a class of people who work at a common activity, generally in a structured or hierarchical organization. A location in which a crew works is called a crewyard or a workyard. The word has nautical resonances: the tasks involved ...

(instructional)

* Cross country

* Dance

Dance is a performing art form consisting of sequences of movement, either improvised or purposefully selected. This movement has aesthetic and often symbolic value. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoire ...

(Ballet, Modern, Hip-Hop; Beg–Adv levels)

* Fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, ...

(instructional)

* Field hockey

Field hockey is a team sport structured in standard hockey format, in which each team plays with ten outfield players and a goalkeeper. Teams must drive a round hockey ball by hitting it with a hockey stick towards the rival team's shooting ...

* Skating (instructional)

* FIT (Fundamentals In Training)

* Football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly ...

* Gunga FIT ("extreme" version of FIT)

* Outdoor Pursuits (S&R)

* Pilates

Pilates (; ) is a type of mind-body exercise developed in the early 20th century by German physical trainer Joseph Pilates, after whom it was named. Pilates called his method "Contrology". It is practiced worldwide, especially in countries suc ...

* SLAM (instructional heerleading

* Soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

* Soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

(intramural)

* Squash (instructional)

* Swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, or other liquid, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Locomotion is achieved through coordinated movement of the limbs and the body to achieve hydrodynamic thrust that r ...

(instructional)

* Tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball cov ...

(instructional)

* Volleyball

Volleyball is a team sport in which two teams of six players are separated by a net. Each team tries to score points by grounding a ball on the other team's court under organized rules. It has been a part of the official program of the Sum ...

(girls')

* Volleyball

Volleyball is a team sport in which two teams of six players are separated by a net. Each team tries to score points by grounding a ball on the other team's court under organized rules. It has been a part of the official program of the Sum ...

(instructional)

* Water polo

Water polo is a competitive team sport played in water between two teams of seven players each. The game consists of four quarters in which the teams attempt to score goals by throwing the ball into the opposing team's goal. The team with th ...

(boys')

* Yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciou ...

* Zumba

Zumba is a fitness program that involves cardio and Latin-inspired dance. It was founded by Colombian dancer and choreographer Beto Pérez in 2001, and by 2012, it had 110,000 locations and 12 million people taking classes weekly. Zumba is a ...

Winter athletic offerings

* Basketball

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams, most commonly of five players each, opposing one another on a rectangular Basketball court, court, compete with the primary objective of #Shooting, shooting a basketball (ball), basketball (appr ...

* Basketball (intramural)

* Dance (Ballet, Modern, Hip-Hop; Beg–Adv levels)

* FIT (Fundamentals In Training)

* Gunga FIT ("extreme" version of FIT)

* Hockey

Hockey is a term used to denote a family of various types of both summer and winter team sports which originated on either an outdoor field, sheet of ice, or dry floor such as in a gymnasium. While these sports vary in specific rules, numbers o ...

* Hockey (intramural)

* Indoor cycling (instructional/cycling pre-season)

* Indoor track

Track and field is a sport that includes athletic contests based on running, jumping, and throwing skills. The name is derived from where the sport takes place, a running track and a grass field for the throwing and some of the jumping event ...

* Junior Basketball (intramural)

* Nordic skiing

Nordic skiing encompasses the various types of skiing in which the toe of the ski boot is fixed to the binding in a manner that allows the heel to rise off the ski, unlike alpine skiing, where the boot is attached to the ski from toe to heel. ...

* Outdoor Pursuits (S&R)

* Recreational cross-country skiing

Cross-country skiing is a form of skiing where skiers rely on their own locomotion to move across snow-covered terrain, rather than using ski lifts or other forms of assistance. Cross-country skiing is widely practiced as a sport and recreatio ...

* SLAM (Spirit Leaders heerleading

* Squash

* Squash (intramural)

* Swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, or other liquid, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Locomotion is achieved through coordinated movement of the limbs and the body to achieve hydrodynamic thrust that r ...

and diving

* Wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat s ...

* Yoga

* Zumba

Zumba is a fitness program that involves cardio and Latin-inspired dance. It was founded by Colombian dancer and choreographer Beto Pérez in 2001, and by 2012, it had 110,000 locations and 12 million people taking classes weekly. Zumba is a ...

Spring athletic offerings

* Baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

* Crew

* Cycling

Cycling, also, when on a two-wheeled bicycle, called bicycling or biking, is the use of cycles for transport, recreation, exercise or sport. People engaged in cycling are referred to as "cyclists", "bicyclists", or "bikers". Apart from ...

* Dance (Ballet, Modern, Hip-Hop; Beg–Adv levels)

* Fencing (instructional)

* FIT (Fundamentals In Training)

* Golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping wi ...

* Gunga FIT ("extreme" version of FIT)

* Lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game was extensiv ...

* Outdoor Pursuits (S&R)

* Pilates

* Softball

Softball is a game similar to baseball played with a larger ball on a smaller field. Softball is played competitively at club levels, the college level, and the professional level. The game was first created in 1887 in Chicago by George Hanc ...

* Squash (instructional)

* Swimming (instructional)

* Tennis

* Tennis (intramural)

* Track

Track or Tracks may refer to:

Routes or imprints

* Ancient trackway, any track or trail whose origin is lost in antiquity

* Animal track, imprints left on surfaces that an animal walks across

* Desire path, a line worn by people taking the shorte ...

* Ultimate Frisbee

Ultimate, originally known as ultimate Frisbee, is a non-contact team sport played with a frisbee Flying disc sports, flung by hand. Ultimate was developed in 1968 by AJ Gator in Maplewood, New Jersey. Although ultimate resembles many traditiona ...

* Ultimate Frisbee (intramural)

* Volleyball (boys')

* Water polo (girls')

* Yoga

Student body

For the 2020-2021 school year, the Andover student body included students from 44 states/territories and 51 countries. Self reportedstudents of color

The term "person of color" ( : people of color or persons of color; abbreviated POC) is primarily used to describe any person who is not considered "white". In its current meaning, the term originated in, and is primarily associated with, the U ...

comprise 41.9% of the student body (Asian 40.1%, Black 10.4%, Hispanic/Latino 9.4%, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander 1.2%, Indigenous Peoples of the Americas 2.3%). Self reported legacy students (defined as students that "have at least one immediate family member who is currently attending or has previously attended Andover.") account for 33.2% of the students.

Andover has its own nomenclature

Nomenclature (, ) is a system of names or terms, or the rules for forming these terms in a particular field of arts or sciences. The principles of naming vary from the relatively informal conventions of everyday speech to the internationally ag ...

for grade levels. Juniors are students in their first year, Lowers are in their second year, Uppers are in their third year, and Seniors are in their fourth year. Andover admits postgraduate students as well ("PGs").

73.7 percent of Andover students live on campus in dorms or houses while day students from the surrounding communities make up the remaining 26.3 percent of the student body.

The Phillipians boast a diverse political landscape, in the 2021 State of the Academy 36.1% identified as Liberal, 13.2% as Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

, 11.3% as Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, 4.0% as Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

, 3.2% as Libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

, 3.2% as Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

, 1.6% did not identify with the above, leaving 21.8% who were unsure as to their political affiliation.

The Phillips Academy Poll

The Phillips Academy Poll (also known as Andover Poll) is a public opinion research institute based at Phillips Academy. The organization studies political sentiments by surveyingregistered voters

In electoral systems, voter registration (or enrollment) is the requirement that a person otherwise eligible to vote must register (or enroll) on an electoral roll, which is usually a prerequisite for being entitled or permitted to vote.

The ru ...

by telephone. The poll’s findings have been covered by MSNBC

MSNBC (originally the Microsoft National Broadcasting Company) is an American news-based pay television cable channel. It is owned by NBCUniversala subsidiary of Comcast. Headquartered in New York City, it provides news coverage and political ...

, Fox News

The Fox News Channel, abbreviated FNC, commonly known as Fox News, and stylized in all caps, is an American multinational conservative cable news television channel based in New York City. It is owned by Fox News Media, which itself is o ...

, BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broadc ...

, ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'', ''Politico

''Politico'' (stylized in all caps), known originally as ''The Politico'', is an American, German-owned political journalism newspaper company based in Arlington County, Virginia, that covers politics and policy in the United States and intern ...

'', ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'', NPR

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other ...

, and ''FiveThirtyEight

''FiveThirtyEight'', sometimes rendered as ''538'', is an American website that focuses on opinion poll analysis, politics, economics, and sports blogging in the United States. The website, which takes its name from the number of electors in th ...

.'' It is a student-led organization and the first public opinion poll to be conducted by an institution of secondary education.

Organization

The Phillips Academy Poll is a student organization at Phillips Academy inAndover, Massachusetts

Andover is a town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. It was settled in 1642 and incorporated in 1646."Andover" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th ed., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 387. As of th ...

. It was founded by Patrick Chen and Alex Shieh, though the two dispute who originally came up with the idea. The organization's polling is funded by the Abbot Academy Fund, a grant-giving organization furthering the ideals of Abbot Academy

Abbot Academy (also known as Abbot Female Seminary and AA) was an independent boarding preparatory school for women boarding and day students in grades 9–12 from 1828 to 1973. Located in Andover, Massachusetts, Abbot Academy was notable as one ...

, which merged with Phillips Academy in 1973.

Methodology

The Phillips Academy Poll conducts surveys viatelephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

, using interactive voice response

Interactive voice response (IVR) is a technology that allows telephone users to interact with a computer-operated telephone system through the use of voice and DTMF tones input with a keypad. In telecommunications, IVR allows customers to interac ...

technology that allows respondents to indicate their responses via the keypad. Outgoing phone calls are initiated with an automated dialing system. The poll's sample is achieved through random digit dialing. Within the area codes

A telephone numbering plan is a type of numbering scheme used in telecommunication to assign telephone numbers to subscriber telephones or other telephony endpoints. Telephone numbers are the addresses of participants in a telephone network, r ...

assigned to the location being polled, phone numbers are dialed at random, and the response rate is approximately 2-3%. Polling results are interpreted by raking

Raking (also called "raking ratio estimation" or "iterative proportional fitting The iterative proportional fitting procedure (IPF or IPFP, also known as biproportional fitting or biproportion in statistics or economics (input-output analysis, etc ...

, also known as iterative proportional fitting. This procedure adjusts the weighting for each response so the sample more accurately reflects the demographics

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

and partisan affiliations of the general electorate.

Criticism

Following the release of its April 2022New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

poll, Andy Smith, the director of the University of New Hampshire

The University of New Hampshire (UNH) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Durham, New Hampshire. It was founded and incorporated in 1866 as a land grant college in Hanover in connection with Dartmouth College ...

Survey Center, criticized The Phillips Academy Poll's use of interactive voice response to conduct polling, publicly questioning, "Why would you want to talk with a computer about your views on politics unless you really want to express your views on politics?" According to the New Yorker

New Yorker or ''variant'' primarily refers to:

* A resident of the State of New York

** Demographics of New York (state)

* A resident of New York City

** List of people from New York City

* ''The New Yorker'', a magazine founded in 1925

* '' The ...

, the poll's computers crashed in its initial polls.

Tuition and financial aid

For the 2021-2022 academic year, Phillips Academy charged boarding students $61,950 and day students $48,020. In the 2018-2019 academic year, Phillips Academy charged boarding students $55,800 and day students $43,300, making it more expensive than HMC schools and among the most expensive boarding schools in the world.Tuition

Tuition payments, usually known as tuition in American English and as tuition fees in Commonwealth English, are fees charged by education institutions for instruction or other services. Besides public spending (by governments and other public bo ...

to Phillips Academy has increased at rate of 4.27% a year since the 2002 academic year, or 3.76% per year over the last decade. There are mandatory fees for boarding students and optional fees on top of tuition. These were an estimated $2400/year plus travel to and from the Academy in the 2017–2018 academic year.

Phillips Academy offers needs-blind financial aid. In the 2021-2022 academic year, 100% of demonstrated financial need was met with 47% of students receiving some form of financial aid and 15% of students receiving full scholarships. Returning students receive an average grant of $40,800.

Affiliations

Andover is a member of the Eight Schools Association, begun informally in 1973–74 and formalized in 2006. Andover was host to the annual meeting of ESA in April 2008. It is also a member of the Ten Schools Admissions Organization, founded in 1956. There is a seven-school overlap of membership between the two groups. In addition, Andover is a member of the G20 Schools group, an international organization of independent secondary schools.Controversies

In 2013, Phillips Academy drew national attention for apparent bias against girls and women, as highlighted by a low number of girls in student leadership. Reports in 2016 and 2017 identified several former teachers in the past who had engaged in inappropriate sexual contact with students. The school hired an independent law firm to investigate allegations of misconduct, and the head of school,John Palfrey

John Gorham Palfrey VII (born 1972) is an American educator, scholar, and law professor. He is an authority on the legal aspects of emerging media and an advocate for Internet freedom, including increased online transparency and accountabilit ...

, and the head of the Board of Trustees, Peter Currie, sent an email to the school community that such transgressions must not recur.

In 2020, an Instagram

Instagram is a photo and video sharing social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. The app allows users to upload media that can be edited with filters and organized by hashtags and geographical tagging. Posts can ...

account, @blackatandover, began circulating stories from anonymous current and former Black-identifying students, many of whom detailed personal experiences with racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

at Phillips Academy. Several anonymous individuals raised concerns about Phillips Academy's disciplinary system, including perceived racial disparities in outcomes, a perceived emphasis on punishment over restorative justice, and an apparent lack of due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual per ...

in discipline procedure outlined by the student handbook. The @blackatandover account was reported on by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', prompting school officials to form an "Anti-Racism Task Force," which released a final report in March 2022.

Notable alumni

Josiah Quincy III

Josiah Quincy III (; February 4, 1772 – July 1, 1864) was an American educator and political figure. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1805–1813), mayor of Boston (1823–1828), and President of Harvard University (1829� ...

File:BurroughsEdgarRice.jpg, Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, ...

File:Jessica_Livingston_in_2007.jpg, Jessica Livingston

Jessica Livingston, born 1971, is an American author and a founding partner of the seed stage venture firm Y Combinator.

She also organized Startup School. Previously, she was the VP of marketing at Adams Harkness Financial Group. She has a B. ...

File:Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr 1859-cropped.jpg, Oliver Wendell Holmes

File:FLOlmstead.jpg, Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co- ...

File:Humphrey Bogart publicity.jpg, Humphrey Bogart

Humphrey DeForest Bogart (; December 25, 1899 – January 14, 1957), nicknamed Bogie, was an American film and stage actor. His performances in Classical Hollywood cinema films made him an American cultural icon. In 1999, the American Film In ...

File:Jack Lemmon - 1968.jpg, Jack Lemmon

John Uhler Lemmon III (February 8, 1925 – June 27, 2001) was an American actor. Considered equally proficient in both dramatic and comic roles, Lemmon was known for his anxious, middle-class everyman screen persona in dramedy pictures, leadi ...

File:Bill Belichick 2012 Shankbone.JPG, Bill Belichick

William Stephen Belichick (; born April 16, 1952) is an American professional football coach who is the head coach of the New England Patriots of the National Football League (NFL). Additionally, he exercises extensive authority over the Patri ...

File:Lachlan Murdoch in May 2013.jpg, Lachlan Murdoch

Lachlan Keith Murdoch (; born 8 September 1971) is a British-Australian businessman and mass media heir. He is the executive chairman of Nova Entertainment, co-chairman of News Corp, executive chairman and CEO of Fox Corporation, and the f ...

Supreme Court Justice

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight Associate Justice of the Supreme ...

( William Henry Moody), six Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

recipients (Civil War: 2; Spanish–American War: 1; World War II: 2; Korean War: 1), five Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make ou ...

(making it one of only four secondary schools in the world to have educated five or more Nobel Prize winners), as well as winners of Tony, Grammy

The Grammy Awards (stylized as GRAMMY), or simply known as the Grammys, are awards presented by the Recording Academy of the United States to recognize "outstanding" achievements in the music industry. They are regarded by many as the most pres ...

, Emmy

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

and Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

. Numerous graduates have become billionaires, including Tim Draper

Timothy Cook Draper (born June 11, 1958) is an American venture capital investor, and founder of Draper Fisher Jurvetson (DFJ),

, venture capitalist; Ed Bass

Edward Perry "Ed" Bass (born September 10, 1945) is an American businessman, financier, philanthropist and environmentalist who lives in Fort Worth, Texas. He financed the Biosphere 2 project, an artificial closed ecological system, whic ...

, philanthropist and environmentalist; Theodore J. Forstmann

Theodore Joseph Forstmann (February 13, 1940 – November 20, 2011) was one of the founding partners of Forstmann Little & Company, a private equity firm, and chairman and CEO of IMG, a global sports and media company. A billionaire, Forstmann ...

, founder of Forstmann Little & Company and IMG img or IMG is an abbreviation for image.

img or IMG may also refer to: