Phil Lamason on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Phillip John Lamason, (15 September 191819 May 2012) was a pilot in the

''New Zealanders with the Royal Air Force. (Vol. 1)''

Published by War History Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Wellington. . He was educated at

, hawkesbaytoday.co.nz, 25 April 2012; retrieved 2 May 2012. Prior to the war, he worked for the Department of Agriculture at

Evening Post, Volume CXXXVIII, Issue 31, p. 6, date 5 August 1944; retrieved 26 April 2011. It was there Lamason took the opportunity of free flying lessons, clocking up 100 hours. He was described as a tall, good-looking man with blue eyes and a broken nose.Burgess, Colin (1995)

''Destination Buchenwald''

Published by Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst NSW. . Lamason joined the RNZAF in September 1940. By April 1942, he had been posted to the After his first tour ended flying Stirlings with 218 Squadron, Lamason then instructed other pilots at 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit. Returning to operations with No. 15 Squadron RAF, Lamason was twice

After his first tour ended flying Stirlings with 218 Squadron, Lamason then instructed other pilots at 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit. Returning to operations with No. 15 Squadron RAF, Lamason was twice

"War hero had 'core of steel'"

''The Dominion Post''; retrieved 26 May 2012. A day after making an emergency landing at an American base in England, Lamason was introduced to, shook hands and spoke with Clark Gable. Lamason was not afraid to speak his mind. On the night of 30/31 March 1944, when 795 bombers were sent to attack Nuremberg, he was very critical of the route chosen, warning his

Telegraph.co.uk, 1 June 2012; retrieved 1 June 2012. On the moonlit night, 95 bombers were lost, its heaviest losses of the entire war during a single raid.

/ref> of No. 15 Squadron RAF, on his 45th operation, when he was shot down during a raid on railway marshalling yards at Massy-Palaiseau near Paris.''In Gestapo Hands''

Evening Post (Wellington, NZ), Volume CXXXIX, Issue 122, p. 4, 25 May 1945; retrieved 22 September 2010. Lamason recalled: Along with his English navigator, Flying Officer Ken Chapman, Lamason was picked up by members of the French Resistance and hidden at various locations for seven weeks. In August 1944, while attempting to reach Spain along the Comet line, Lamason and Chapman were captured by the Gestapo in Paris after they were betrayed by the French double agent

Along with his English navigator, Flying Officer Ken Chapman, Lamason was picked up by members of the French Resistance and hidden at various locations for seven weeks. In August 1944, while attempting to reach Spain along the Comet line, Lamason and Chapman were captured by the Gestapo in Paris after they were betrayed by the French double agent

Phil Lamason: Humble Bay pilot

. HawkesBayToday.co.nz, 25 April 2012; retrieved 2 May 2012. After

''Prisoners of War in the Second World War''

, vac-acc.gc.ca; retrieved 6 January 2009.National Museum of the USAF (2008)

''Fact Sheets: Allied Victims of the Holocaust''

, nationalmuseum.af.mil; retrieved 5 January 2009. Consequently, Lamason was among a group of 168 Allied airmen from Great Britain, United States,

''In the Shadows of War''

Henry Holt and Co, New York. After five days travel, during which the airmen received very little food or water, they arrived at Buchenwald on 20 August 1944.Lambert, Max (2005, pp. 464–68)

''Night After Night: New Zealanders in Bomber Command''

Harper Collins, Auckland. . Kinnis, Arthur and Booker, Stanley (1999)

''168 Jump Into Hell''

Victoria B.C. . Buchenwald was a labour camp of about 60,000 inmates of mainly Russian POWs, but also common criminals, religious prisoners (including Jews), and various political prisoners from Germany, France, Poland, and Czechoslovakia.Crocker, Brandon (2008)

An American in Buchenwald

. ''The American Spectator''. Retrieved on 4 January 2009. It was known for its brutality and barbaric medical experiments.Buchenwald

(2010). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington; retrieved 25 August 2010. Upon arrival, Lamason, as ranking officer, demanded an interview with the camp commandant,

''The White Rabbit''

Published by Cassell, London. Dyreborg, Erik (2003, pp. 287–93)

''The young ones: American airmen of WW II''

Published by iUniverse, Inc., Lincoln, NE. Little Camp was a quarantine section of Buchenwald where the prisoners received the least food and harshest treatment.Moser, Joseph and Baron, Gerald (2009)

''A fighter pilot in Buchenwald''

Published by Edens Veil Media, Bellingham, WA. . After their first meal, Lamason stepped forward and said: Lamason then instructed the group not to trust the SS, or provoke them in any way because as they had experienced on the train, the guards were unpredictable and trigger-happy. Also, they were not to explore the camp because of the chance of breaking unknown rules, but to stay together and keep as far away from the guards as possible.Harvie, John (1995)

Lamason then instructed the group not to trust the SS, or provoke them in any way because as they had experienced on the train, the guards were unpredictable and trigger-happy. Also, they were not to explore the camp because of the chance of breaking unknown rules, but to stay together and keep as far away from the guards as possible.Harvie, John (1995)

''Missing in Action''

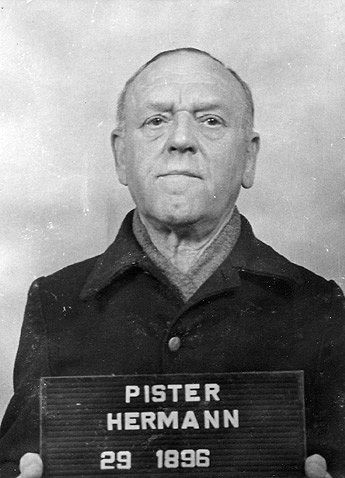

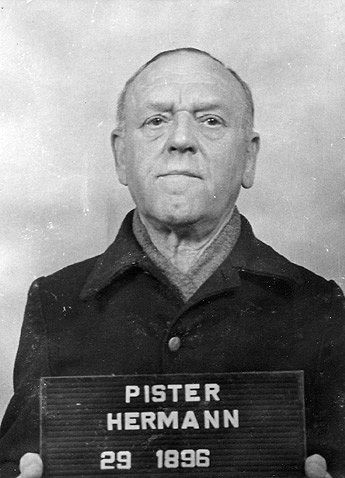

Published by McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal. . He further stated that acting on the group's behalf, he would make further contact with the camp authorities for recognition of their rights. Lamason then proceeded to organise the airmen into groups by nationality and appointed a For the next six weeks, Lamason negotiated with Pister and the German camp authorities, but his requests to have the airmen transferred to proper POW camps were denied.Australian War Memorial (2008). AWM Collection Record: P02988.001

For the next six weeks, Lamason negotiated with Pister and the German camp authorities, but his requests to have the airmen transferred to proper POW camps were denied.Australian War Memorial (2008). AWM Collection Record: P02988.001

Philip J. Lamason

. Retrieved 4 January 2009. One captured British airman,

Movie about pilot Joe Moser's story of WWII survival to premier in Bellingham

''The Bellingham Herald''; retrieved 3 October 2011. After a tense stand-off, during which time Lamason thought he would be shot, the SS officer eventually backed down.Phil Lamason – Refusal to work in Buchenwald Factories

Mike Dorsey video interview with Phil Lamason (June 2010); retrieved 18 July 2010. Most airmen doubted they would ever get out of Buchenwald because their documents were stamped with the acronym "DIKAL" (), or "not to be transferred to another camp". At great risk, Lamason and Burney secretly smuggled a note through a trusted Russian prisoner, who worked at the nearby

''Spirit of resistance''

Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, UK. . Unsung heroes of the bombing war

(2005). ''The New Zealand Herald''. Retrieved on 13 January 2009. The message requested in part, that an officer pass the information to Berlin, and for the Luftwaffe to intercede on behalf of the airmen. Lamason understood that the Luftwaffe would be sympathetic to their predicament, as they would not want their captured men treated in the same way; he also knew that the Luftwaffe had the political connections to get the airmen transferred to a POW camp. Eventually, Lamason's persistence paid off. Under the pretence of inspecting aerial bomb damage near the camp, two Luftwaffe officers (including Hannes Trautloft) made contact with the airmen and also spoke to Lamason. Convinced the airmen were not spies, but bona-fide airmen, Trautloft reported his findings to command. After reading the report, an outraged Hermann Göring demanded 'at the highest level' the transfer of the airmen to Luftwaffe control. Unknown to all airmen except Lamason, their execution had been scheduled for 26 October, if they remained at Buchenwald.Hope, Derek (2008)

A flier is remembered

''Royal New Zealand Air Force''. Retrieved on 6 January 2009.Bard, Mitchell (2004, pp. 259–260)

''The Complete Idiot's Guide to World War II''

Alpha Books. . News of the airmen's scheduled execution had been conveyed to Lamason by a German political prisoner,

''The theory and practice of hell: the German concentration camps and the system behind them''

Berkeley Books, California. . Lamason discussed the information at length with Yeo-Thomas, Burney and Robert and they concluded there was little that could be done to avert the mass execution. Lamason decided not to inform the airmen, but to keep this information to himself to keep morale high and in the slight hope the Luftwaffe would intervene in time. On the night of 19 October, seven days before their scheduled execution, 156 of the 168 airmen, including Lamason, were transferred from Buchenwald to

During the 1980s and 1990s, Lamason was a regular speaker at KLB (initials for Konzentrationslager Buchenwald) Club reunions, a club formed by the Allied airmen while detained in Buchenwald. Lamason was also a member of the

During the 1980s and 1990s, Lamason was a regular speaker at KLB (initials for Konzentrationslager Buchenwald) Club reunions, a club formed by the Allied airmen while detained in Buchenwald. Lamason was also a member of the

(1994). National Film Board of Canada; retrieved 22 July 2010. Lamason was portrayed in the History Channel's 2004 documentary "''Shot from the Sky''", about the real life saga of B-17 pilot Roy Allen, one of the captured airmen taken to Buchenwald. In April 2005, Lamason, then 86, recollected the events of Buchenwald on TV New Zealand. In June 2010, Lamason, then 91, was interviewed again about his experience at Buchenwald by Mike Dorsey. This and other interviews with Lamason are featured in Dorsey's 2011 documentary film titled, ''Lost Airmen of Buchenwald'', which tells the complete story of the 168 Allied airmen who were sent to Buchenwald, including Lamason. Mike Dorsey said Lamason remained scarred by his experiences to the extent that Dorsey said “I have a feeling that Lamason, to put it in a word, has no time for the Germans.” Lamason died at his home on 19 May 2012, on the farm outside Dannevirke where he had lived for over 60 years. He was 93 and at the time of his death, survived by two sons and two daughters. He was predeceased by his wife, Joan (née Hopkins), who died in 2007, and was buried with her at Mangatera Cemetery.Lambert, Max (20 May 2012)

"Kiwi World War II hero dies"

Fairfax New Zealand Ltd; retrieved 20 May 2012. In November 2015, it was announced that a book recounting and honouring Lamason's life would be written by

''World War II hero from Dannevirke's story makes it into print''

Hawke's Bay Today. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

''Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences''

Published by Frederic H. Martini. . * Ydier, Francois (2016)

''The Boy and the Bomber''

Published by Mention the War Publications. . * Samuel, Wolfgang (2015)

''In Defense of Freedom: Stories of Courage and Sacrifice of World War II Army Air Forces Flyers''

Published by University Press of Mississippi. . . * Smith, Stephen (2015)

''From St Vith to Victory: 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron and the Campaign Against Nazi Germany''

Published by Pen and Sword Books Ltd, Barnsley England. * Walton, Marilyn and Eberhardt, Michael (2014)

''From Interrogation to Liberation''

Published by Author House. . . * Clutton-Brock, Oliver and Crompton, Raymond (2014)

''The Long Road''

Published by Grub Street Publishing, Havertown. . . * Gilbert, Adrian (2006)

''POW: Allied prisoners in Europe, 1939–1945''

Published John Murray, London. . . * Clutton-Brock, Oliver (2003)

''Footprints on the sands of time: RAF Bomber Command prisoners-of-war 1939–1945''

Published by Grub Street, London. . * Bard, Michael Geoffery (1996)

''Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler's Camps''

Published by Westview Press, Washington. . * Burney, Christopher (1946)

''The dungeon democracy''

Published by Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York.

''Lost Airmen of Buchenwald''

A documentary film featuring Phil Lamason

''I Would Not Step Back...''

The Phil Lamason Project {{DEFAULTSORT:Lamason, Phil 1918 births 2012 deaths Buchenwald concentration camp survivors New Zealand military personnel of World War II New Zealand prisoners of war in World War II New Zealand World War II pilots Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) People from Dannevirke Royal Air Force officers Royal New Zealand Air Force personnel Shot-down aviators World War II prisoners of war held by Germany People from Napier, New Zealand People educated at Napier Boys' High School Massey University alumni Burials at Mangatera Cemetery

Royal New Zealand Air Force

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) ( mi, Te Tauaarangi o Aotearoa, "The Warriors of the Sky of New Zealand"; previously ', "War Party of the Blue") is the aerial service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed from New Zeala ...

(RNZAF) during the Second World War, who rose to prominence as the senior officer in charge of 168 Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

airmen taken to Buchenwald concentration camp

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

, Germany, in August 1944. Raised in Napier, he joined the RNZAF in September 1940, and by April 1942 was a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

serving with the Royal Air Force in Europe. On 8 June 1944, Lamason was in command of a Lancaster heavy bomber that was shot down during a raid on railway marshalling yards near Paris. Bailing out, he was picked up by members of the French Resistance and hidden at various locations for seven weeks. While attempting to reach Spain along the Comet line, Lamason was betrayed by a double agent within the Resistance and seized by the Gestapo.

After interrogation

Interrogation (also called questioning) is interviewing as commonly employed by law enforcement officers, military personnel, intelligence agencies, organized crime syndicates, and terrorist organizations with the goal of eliciting useful informa ...

, he was taken to Fresnes prison. Classified as a "Terrorflieger" (terror flier), he was not accorded prisoner-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

(POW) status, but instead treated as a criminal and spy. By 15 August 1944, Lamason was senior officer of a group of 168 captured Allied airmen who were taken by train to Buchenwald concentration camp, arriving there five days later.

At Buchenwald, the airmen were fully shaved, starved, denied shoes, and for three weeks forced to sleep outside without shelter in one of the sub-camps known as "Little Camp". As senior officer, Lamason took control and instilled a level of military discipline and bearing.

For several weeks Lamason negotiated with the camp authorities to have the airmen transferred to a POW camp, but his requests were denied. At great risk, Lamason secretly got word to the Luftwaffe of the Allied airmen's captivity and, seven days before their scheduled execution, 156 of the 168 prisoners were transferred to Stalag Luft III

, partof = ''Luftwaffe''

, location = Sagan, Lower Silesia, Nazi Germany (now Żagań, Poland)

, image =

, caption = Model of the set used to film the movie ''The Great Escape.'' It depicts a smaller version of a single compound in ''Stalag ...

. Most of the airmen credit their survival at Buchenwald to the leadership and determination of Lamason. After the war, he moved to Dannevirke

Dannevirke ( "Earthworks (archaeology), work of the Danes", a reference to Danevirke; mi, Taniwaka, lit= or ''Tāmaki-nui-a-Rua'', the area where the town is), is a rural service town in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of the North Island, New ...

and became a farmer until his retirement. During the 1980s and 1990s, he was a regular speaker at KLB Club

Between 20 August and 19 October 1944, 168 Allied airmen were held prisoner at Buchenwald concentration camp. Colloquially, they described themselves as the KLB Club (from german: Konzentrationslager Buchenwald)... Of them, 166 airmen survive ...

and POW reunions.

Early career

Lamason was born and raised inNapier Napier may refer to:

People

* Napier (surname), including a list of people with that name

* Napier baronets, five baronetcies and lists of the title holders

Given name

* Napier Shaw (1854–1945), British meteorologist

* Napier Waller (1893–19 ...

, a city in New Zealand's North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

, on 15 September 1918.Thompson, H. L. (1953)''New Zealanders with the Royal Air Force. (Vol. 1)''

Published by War History Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Wellington. . He was educated at

Napier Boys' High School

Napier Boys' High School is a secondary boys' school in, Napier, New Zealand. It currently has a school roll of approximately pupils. The school provides education from Year 9 to Year 13.

Notable alumni

Business

* Rod Drury – chief execu ...

and Massey University

Massey University ( mi, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa) is a university based in Palmerston North, New Zealand, with significant campuses in Albany and Wellington. Massey University has approximately 30,883 students, 13,796 of whom are extramural or ...

( Palmerston North campus) where he was awarded a Diploma

A diploma is a document awarded by an educational institution (such as a college or university) testifying the recipient has graduated by successfully completing their courses of studies. Historically, it has also referred to a charter or offici ...

in Sheep farming.

During this period, Lamason described himself as "a bit of a ratbag".Anzac Day: From teen ratbag to hero, hawkesbaytoday.co.nz, 25 April 2012; retrieved 2 May 2012. Prior to the war, he worked for the Department of Agriculture at

New Plymouth

New Plymouth ( mi, Ngāmotu) is the major city of the Taranaki region on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is named after the English city of Plymouth, Devon from where the first English settlers to New Plymouth migrated. ...

as a stock inspector.AWARD OF BAR TO D.F.CEvening Post, Volume CXXXVIII, Issue 31, p. 6, date 5 August 1944; retrieved 26 April 2011. It was there Lamason took the opportunity of free flying lessons, clocking up 100 hours. He was described as a tall, good-looking man with blue eyes and a broken nose.Burgess, Colin (1995)

''Destination Buchenwald''

Published by Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst NSW. . Lamason joined the RNZAF in September 1940. By April 1942, he had been posted to the

European theatre of operations

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

as a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

in No. 218 Squadron RAF

No. 218 Squadron RAF was a squadron of the Royal Air Force. It was also known as No 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron after the Governor of the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) and people of the Gold Coast officially adopted the squadron.

History

World War I ...

. During a bombing raid on Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, he was in command of an aircraft that was attacked by an enemy fighter and badly damaged, but managed to return to base. As a result of his actions, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) on 15 May 1942. The citation read:

After his first tour ended flying Stirlings with 218 Squadron, Lamason then instructed other pilots at 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit. Returning to operations with No. 15 Squadron RAF, Lamason was twice

After his first tour ended flying Stirlings with 218 Squadron, Lamason then instructed other pilots at 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit. Returning to operations with No. 15 Squadron RAF, Lamason was twice Mentioned in Despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

, first on 2 June 1943 and again, having received promotion to acting squadron leader, on 14 January 1944. He was awarded a Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

to his DFC on 27 June 1944, for "courage and devotion to duty of a high order" and "vigorous determination" in attacks on Berlin and other heavily defended targets. Lamason was presented his award after the war by King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of Ind ...

at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

, where he met and befriended a young Princess Elizabeth.Chatterton, Tracey (26 May 2012)"War hero had 'core of steel'"

''The Dominion Post''; retrieved 26 May 2012. A day after making an emergency landing at an American base in England, Lamason was introduced to, shook hands and spoke with Clark Gable. Lamason was not afraid to speak his mind. On the night of 30/31 March 1944, when 795 bombers were sent to attack Nuremberg, he was very critical of the route chosen, warning his

station commander

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

that heavy losses could be expected.Squadron Leader Phil Lamason obituaryTelegraph.co.uk, 1 June 2012; retrieved 1 June 2012. On the moonlit night, 95 bombers were lost, its heaviest losses of the entire war during a single raid.

Buchenwald

On 8 June 1944, Lamason was serving as a flight commander in a Lancaster LM575 LS-HRecord for Lancaster LM575 on ''lostaircraft.com''/ref> of No. 15 Squadron RAF, on his 45th operation, when he was shot down during a raid on railway marshalling yards at Massy-Palaiseau near Paris.''In Gestapo Hands''

Evening Post (Wellington, NZ), Volume CXXXIX, Issue 122, p. 4, 25 May 1945; retrieved 22 September 2010. Lamason recalled:

Along with his English navigator, Flying Officer Ken Chapman, Lamason was picked up by members of the French Resistance and hidden at various locations for seven weeks. In August 1944, while attempting to reach Spain along the Comet line, Lamason and Chapman were captured by the Gestapo in Paris after they were betrayed by the French double agent

Along with his English navigator, Flying Officer Ken Chapman, Lamason was picked up by members of the French Resistance and hidden at various locations for seven weeks. In August 1944, while attempting to reach Spain along the Comet line, Lamason and Chapman were captured by the Gestapo in Paris after they were betrayed by the French double agent Jacques Desoubrie

Jacques Desoubrie (1922 – 1949)Review

of Patrice Miannay's ''Dictionnaires des agents doubles dans ...

for 10,000 francs each.McKay, Christineof Patrice Miannay's ''Dictionnaires des agents doubles dans ...

Phil Lamason: Humble Bay pilot

. HawkesBayToday.co.nz, 25 April 2012; retrieved 2 May 2012. After

interrogation

Interrogation (also called questioning) is interviewing as commonly employed by law enforcement officers, military personnel, intelligence agencies, organized crime syndicates, and terrorist organizations with the goal of eliciting useful informa ...

at the Gestapo headquarters in Paris, they were taken to Fresnes Prison. Many fliers were classified as "Terrorflieger" (terror flier) by the Germans, and were not given a trial. The most common act for Allied airmen to be classified a terror flier was to be captured in civilian clothing and/or without their dog tags. The German Foreign Office decided that these captured enemy airmen should not be given the legal status of prisoner of war (POWs) but should instead be treated as criminals and spies.Veterans Affairs Canada (2006)''Prisoners of War in the Second World War''

, vac-acc.gc.ca; retrieved 6 January 2009.National Museum of the USAF (2008)

''Fact Sheets: Allied Victims of the Holocaust''

, nationalmuseum.af.mil; retrieved 5 January 2009. Consequently, Lamason was among a group of 168 Allied airmen from Great Britain, United States,

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, Canada, New Zealand and Jamaica who—along with over 2,500 French prisoners—were taken by train in overcrowded cattle boxcars from Fresnes Prison outside Paris to Buchenwald concentration camp

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

. As the airmen were herded into the boxcars, Lamason protested about the poor treatment of the airmen, only to be struck in the face by an SS guard. Lamason fell to the ground and captured pilot Roy Allen watched as an SS Major pulled a Luger from his holster and thought Lamason would be shot on the spot.Childers, Thomas (2004)''In the Shadows of War''

Henry Holt and Co, New York. After five days travel, during which the airmen received very little food or water, they arrived at Buchenwald on 20 August 1944.Lambert, Max (2005, pp. 464–68)

''Night After Night: New Zealanders in Bomber Command''

Harper Collins, Auckland. . Kinnis, Arthur and Booker, Stanley (1999)

''168 Jump Into Hell''

Victoria B.C. . Buchenwald was a labour camp of about 60,000 inmates of mainly Russian POWs, but also common criminals, religious prisoners (including Jews), and various political prisoners from Germany, France, Poland, and Czechoslovakia.Crocker, Brandon (2008)

An American in Buchenwald

. ''The American Spectator''. Retrieved on 4 January 2009. It was known for its brutality and barbaric medical experiments.Buchenwald

(2010). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington; retrieved 25 August 2010. Upon arrival, Lamason, as ranking officer, demanded an interview with the camp commandant,

Hermann Pister

Hermann Pister (21 February 1885 – 28 September 1948) was an SS Oberführer (Senior Colonel) and commandant of Buchenwald concentration camp from 21 January 1942 until April 1945.

Early life

Pister was the son of a financial secretary in Lübe ...

, which he was granted. He insisted that the airmen be treated as POWs under the Geneva Conventions and be sent to a POW camp. The commandant agreed that their arrival at Buchenwald was a "mistake" but they remained there anyway. The airmen were given the same poor treatment and beatings as the other inmates. For the first three weeks at Buchenwald, the prisoners were totally shaved, denied shoes and forced to sleep outside without shelter in one of Buchenwald's sub-camps, known as 'Little Camp'.Marshall, Bruce (2000, pp. 193–94)''The White Rabbit''

Published by Cassell, London. Dyreborg, Erik (2003, pp. 287–93)

''The young ones: American airmen of WW II''

Published by iUniverse, Inc., Lincoln, NE. Little Camp was a quarantine section of Buchenwald where the prisoners received the least food and harshest treatment.Moser, Joseph and Baron, Gerald (2009)

''A fighter pilot in Buchenwald''

Published by Edens Veil Media, Bellingham, WA. . After their first meal, Lamason stepped forward and said:

Lamason then instructed the group not to trust the SS, or provoke them in any way because as they had experienced on the train, the guards were unpredictable and trigger-happy. Also, they were not to explore the camp because of the chance of breaking unknown rules, but to stay together and keep as far away from the guards as possible.Harvie, John (1995)

Lamason then instructed the group not to trust the SS, or provoke them in any way because as they had experienced on the train, the guards were unpredictable and trigger-happy. Also, they were not to explore the camp because of the chance of breaking unknown rules, but to stay together and keep as far away from the guards as possible.Harvie, John (1995)''Missing in Action''

Published by McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal. . He further stated that acting on the group's behalf, he would make further contact with the camp authorities for recognition of their rights. Lamason then proceeded to organise the airmen into groups by nationality and appointed a

Commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

within each group. Lamason did not do this just to improve their morale but because he also saw it as his responsibility to carry on his war duties despite the adverse circumstances. Captured US pilot Joe Moser believed that Lamason also did this because if the right opportunity presented itself, the group would be able to operate much more effectively if military discipline and operations were applied.

Lamason's leadership boosted the airmen's spirits and gave them hope while instilling a level of discipline and bearing. One of the first assignments Lamason gave was to mount a guard detail, both day and night, to prevent pilfering by other inmates, which had begun during their first night at camp. During their incarceration

Imprisonment is the restraint of a person's liberty, for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is "false imprisonment". Imprisonment does not necessari ...

, Lamason insisted the airmen march, parade

A parade is a procession of people, usually organized along a street, often in costume, and often accompanied by marching bands, float (parade), floats, or sometimes large balloons. Parades are held for a wide range of reasons, but are usually ce ...

and act as a military unit

Military organization or military organisation is the structuring of the armed forces of a state so as to offer such military capability as a national defense policy may require. In some countries paramilitary forces are included in a nation' ...

.

Within days of their arrival, Lamason met Edward Yeo-Thomas, a British spy being held at Buchenwald under the alias

Alias may refer to:

* Pseudonym

* Pen name

* Nickname

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Alias'' (2013 film), a 2013 Canadian documentary film

* ''Alias'' (TV series), an American action thriller series 2001–2006

* ''Alias the ...

Kenneth Dodkin. Lamason, who knew the real Dodkin quite well, immediately became suspicious and later confided in Christopher Burney

Christopher Arthur Geoffrey Burney MBE (1917 – 18 December 1980) was an upper-class Englishman who served in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II.

Biography

In 1941, Pierre de Vomécourt organized AUTOGYRO, one of the fi ...

, who assured Lamason the cover was legitimate. Through Yeo-Thomas and Burney, Lamason was introduced to two Russian colonels, senior members of the International Camp Committee, an illegal underground

Underground most commonly refers to:

* Subterranea (geography), the regions beneath the surface of the Earth

Underground may also refer to:

Places

* The Underground (Boston), a music club in the Allston neighborhood of Boston

* The Underground (S ...

resistance group of prisoners in the main camp.

As senior officer, Lamason had access to the main camp and quickly built a rapport with the group. As a result, he was able to secure extra blankets, clothes, clogs

Clogs are a type of footwear made in part or completely from wood. Used in many parts of the world, their forms can vary by culture, but often remained unchanged for centuries within a culture.

Traditional clogs remain in use as protective fo ...

and food for the airmen. Lamason also built a rapport with two other prisoners; French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

scientist Alfred Balachowsky

Alfred Serge Balachowsky (15 August 1901 – 24 December 1983) was a French entomologist born in Russia. He specialised in Coccoidea but also worked on Coleoptera. Balachowsky worked at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle (MNHN). In 1948 ...

and Dutch Olympian trainer Jan Robert. Both men had developed trustworthy contacts within the camp administrative area and were able to provide Lamason with reliable intelligence that assisted in the survival of the airmen.

For the next six weeks, Lamason negotiated with Pister and the German camp authorities, but his requests to have the airmen transferred to proper POW camps were denied.Australian War Memorial (2008). AWM Collection Record: P02988.001

For the next six weeks, Lamason negotiated with Pister and the German camp authorities, but his requests to have the airmen transferred to proper POW camps were denied.Australian War Memorial (2008). AWM Collection Record: P02988.001Philip J. Lamason

. Retrieved 4 January 2009. One captured British airman,

Pilot Officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

Splinter Spierenburg, was a Dutchman flying for the Royal Air Force. Spierenburg, who spoke fluent German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

, regularly acted as an interpreter for Lamason when he negotiated with the camp authorities.

As Buchenwald was a forced labour camp, the German authorities had intended to put the 168 airmen to work as slave labor in the nearby armament factories. Consequently, Lamason was ordered by an SS officer to instruct the airmen to work, or he would be immediately executed by firing squad. Lamason refused to give the order and informed the officer that they were soldiers and could not and would not participate in war production.Kahn, Dean (4 July 2011)Movie about pilot Joe Moser's story of WWII survival to premier in Bellingham

''The Bellingham Herald''; retrieved 3 October 2011. After a tense stand-off, during which time Lamason thought he would be shot, the SS officer eventually backed down.Phil Lamason – Refusal to work in Buchenwald Factories

Mike Dorsey video interview with Phil Lamason (June 2010); retrieved 18 July 2010. Most airmen doubted they would ever get out of Buchenwald because their documents were stamped with the acronym "DIKAL" (), or "not to be transferred to another camp". At great risk, Lamason and Burney secretly smuggled a note through a trusted Russian prisoner, who worked at the nearby

Nohra

Nohra is a village and a former municipality in the Weimarer Land district of Thuringia, Germany. Since December 2019, it is part of the municipality Grammetal. On 1 December 2007, the former municipality Utzberg was incorporated by Nohra.

Nohr ...

airfield, to the German Luftwaffe of their captivity at the camp.Perrin, Nigel (2008, pp. 149–50)''Spirit of resistance''

Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, UK. . Unsung heroes of the bombing war

(2005). ''The New Zealand Herald''. Retrieved on 13 January 2009. The message requested in part, that an officer pass the information to Berlin, and for the Luftwaffe to intercede on behalf of the airmen. Lamason understood that the Luftwaffe would be sympathetic to their predicament, as they would not want their captured men treated in the same way; he also knew that the Luftwaffe had the political connections to get the airmen transferred to a POW camp. Eventually, Lamason's persistence paid off. Under the pretence of inspecting aerial bomb damage near the camp, two Luftwaffe officers (including Hannes Trautloft) made contact with the airmen and also spoke to Lamason. Convinced the airmen were not spies, but bona-fide airmen, Trautloft reported his findings to command. After reading the report, an outraged Hermann Göring demanded 'at the highest level' the transfer of the airmen to Luftwaffe control. Unknown to all airmen except Lamason, their execution had been scheduled for 26 October, if they remained at Buchenwald.Hope, Derek (2008)

A flier is remembered

''Royal New Zealand Air Force''. Retrieved on 6 January 2009.Bard, Mitchell (2004, pp. 259–260)

''The Complete Idiot's Guide to World War II''

Alpha Books. . News of the airmen's scheduled execution had been conveyed to Lamason by a German political prisoner,

Eugen Kogon

Eugen Kogon (2 February 1903 – 24 December 1987) was a historian and Nazi concentration camp survivor. A well-known Christian opponent of the Nazi Party, he was arrested more than once and spent six years at Buchenwald concentration camp. Kogon ...

, who had a reliable contact within the camp administrative area.Kogon, Eugen (1980, p. 250)''The theory and practice of hell: the German concentration camps and the system behind them''

Berkeley Books, California. . Lamason discussed the information at length with Yeo-Thomas, Burney and Robert and they concluded there was little that could be done to avert the mass execution. Lamason decided not to inform the airmen, but to keep this information to himself to keep morale high and in the slight hope the Luftwaffe would intervene in time. On the night of 19 October, seven days before their scheduled execution, 156 of the 168 airmen, including Lamason, were transferred from Buchenwald to

Stalag Luft III

, partof = ''Luftwaffe''

, location = Sagan, Lower Silesia, Nazi Germany (now Żagań, Poland)

, image =

, caption = Model of the set used to film the movie ''The Great Escape.'' It depicts a smaller version of a single compound in ''Stalag ...

by the Luftwaffe.

Two airmen died at Buchenwald. The other ten, who were too ill to be moved with the main group, were transported to Stalag Luft III in small groups over a period of several weeks. In the two months at Buchenwald, Lamason had lost 19 kilograms (42 lbs) and had contracted diphtheria and dysentery. At Stalag Luft III, he spent a month in the infirmary

Infirmary may refer to:

*Historically, a hospital, especially a small hospital

*A first aid room in a school, prison, or other institution

*A dispensary (an office that dispenses medications)

*A clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambu ...

recovering. In late January 1945, all Stalag Luft III POWs were force-marched to other POW camps further inside Germany. Lamason and Chapman were marched to Stalag III-A outside Luckenwalde, where they remained until liberated by the Russian army at the end of the war in Europe. Lamason and Chapman were taken to Hildesheim airfield and flown to Brussels and then on to England.

Many airmen credit their survival at Buchenwald to the leadership and determination of Lamason. Captured pilot Stratton Appleman stated that "they were very fortunate to have Lamason as their leader". Another airman, Joe Moser, stated that Lamason was a great leader whom he would have been glad to follow anywhere he asked. British pilot James Stewart described Lamason as "a wonderful unsung hero". In the book ''168 Jump into Hell'', Lamason was described as having single-minded determination, selflessness, cold courage and forcefulness in the face of the threat of execution by the camp authorities because he was their leader and said that Lamason quickly established himself as a legendary figure in the airmen's eyes. In the National Film Board of Canada 1994 documentary, ''The Lucky Ones: Allied Airmen and Buchenwald'', captured pilot Tom Blackham

Tom or TOM may refer to:

* Tom (given name), a diminutive of Thomas or Tomás or an independent Aramaic given name (and a list of people with the name)

Characters

* Tom Anderson, a character in '' Beavis and Butt-Head''

* Tom Beck, a character ...

stated that Lamason was not only the senior officer, but also their natural leader. Lamason emerged from Buchenwald with a giant reputation. In the book ''Destination Buchenwald'', Lamason stated he felt deeply honoured to have been the senior officer during the Buchenwald period.

Aftermath and later life

Following their liberation and return to England, Lamason was asked to consider commanding one of the Okinawa squadrons for the final attack on Japan. However, the RNZAF refused and Lamason returned to New Zealand, arriving there the day after theatomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

was dropped on Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

. He was discharged from the air force on 16 December 1945.

In 1946, Lamason was asked to be the lead pilot to test the flight paths for a new British airport. As part of the agreement, he was offered a farm in Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Berk ...

. However, family said he needed to be home instead and Heathrow Airport

Heathrow Airport (), called ''London Airport'' until 1966 and now known as London Heathrow , is a major international airport in London, England. It is the largest of the six international airports in the London airport system (the others be ...

went ahead without him. In 1948, Lamason moved to Dannevirke

Dannevirke ( "Earthworks (archaeology), work of the Danes", a reference to Danevirke; mi, Taniwaka, lit= or ''Tāmaki-nui-a-Rua'', the area where the town is), is a rural service town in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of the North Island, New ...

, a small rural community north east of Palmerston North where he acquired 406 acres and became a farmer until his retirement.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Lamason was a regular speaker at KLB (initials for Konzentrationslager Buchenwald) Club reunions, a club formed by the Allied airmen while detained in Buchenwald. Lamason was also a member of the

During the 1980s and 1990s, Lamason was a regular speaker at KLB (initials for Konzentrationslager Buchenwald) Club reunions, a club formed by the Allied airmen while detained in Buchenwald. Lamason was also a member of the Caterpillar Club

The Caterpillar Club is an informal association of people who have successfully used a parachute to bail out of a disabled aircraft. After authentication by the parachute maker, applicants receive a membership certificate and a distinctive lapel ...

, an informal association of people who have successfully used a parachute

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, who ...

to bail out of a disabled aircraft.

Lamason hid the fact for 39 years that the order for the airmen's execution was given and scheduled for 26 October 1944, first mentioning it at a Canadian POW convention in Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

in 1983. In May 1987, the New Zealand government

, background_color = #012169

, image = New Zealand Government wordmark.svg

, image_size=250px

, date_established =

, country = New Zealand

, leader_title = Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern

, appointed = Governor-General

, main_organ =

, ...

in Wellington approved a fund to compensate servicemen held in German concentration camps and Lamason was awarded $13,000. However, Lamason was never formally honoured by his homeland for his leading role in saving the lives of the Allied airmen at Buchenwald.

In 1994, the National Film Board of Canada released a documentary movie titled, “''The Lucky Ones: Allied Airmen and Buchenwald''”, in which former Allied airmen recounted their personal and collective stories of life before, during and after Buchenwald. Lamason was interviewed and mentioned throughout the documentary.''The Lucky Ones: Allied Airmen and Buchenwald''(1994). National Film Board of Canada; retrieved 22 July 2010. Lamason was portrayed in the History Channel's 2004 documentary "''Shot from the Sky''", about the real life saga of B-17 pilot Roy Allen, one of the captured airmen taken to Buchenwald. In April 2005, Lamason, then 86, recollected the events of Buchenwald on TV New Zealand. In June 2010, Lamason, then 91, was interviewed again about his experience at Buchenwald by Mike Dorsey. This and other interviews with Lamason are featured in Dorsey's 2011 documentary film titled, ''Lost Airmen of Buchenwald'', which tells the complete story of the 168 Allied airmen who were sent to Buchenwald, including Lamason. Mike Dorsey said Lamason remained scarred by his experiences to the extent that Dorsey said “I have a feeling that Lamason, to put it in a word, has no time for the Germans.” Lamason died at his home on 19 May 2012, on the farm outside Dannevirke where he had lived for over 60 years. He was 93 and at the time of his death, survived by two sons and two daughters. He was predeceased by his wife, Joan (née Hopkins), who died in 2007, and was buried with her at Mangatera Cemetery.Lambert, Max (20 May 2012)

"Kiwi World War II hero dies"

Fairfax New Zealand Ltd; retrieved 20 May 2012. In November 2015, it was announced that a book recounting and honouring Lamason's life would be written by

Waipukurau

Waipukurau is the largest town in the Central Hawke's Bay District on the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is located on the banks of the Tukituki River, 7 kilometres south of Waipawa and 50 kilometres southwest of Hastings.

H ...

author Hilary Pedersen by September 2018 (what would have been Lamason's 100th birthday). The book titled, ''I Would Not Step Back ... The Phil Lamason Story'' was launched at Dannevirke in February 2018.McKay, Christine (4 December 2017)''World War II hero from Dannevirke's story makes it into print''

Hawke's Bay Today. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

See also

* ''The Boys of Buchenwald

''The Boys of Buchenwald'' is a 2002 documentary film produced by Paperny Films that examines how the child survivors of the Buchenwald concentration camp had to integrate themselves back into normal society after having experienced the brutality ...

'' – documentary film about the child survivors of Buchenwald concentration camp

* Karl and Ilse Koch; The first Commandant of Buchenwald and his wife, also known as the ''Bitch of Buchenwald''

* Number of deaths in Buchenwald The number of deaths in the Buchenwald concentration camp is estimated to have been 56,545, a mortality rate of 20% averaged over all prisoners transferred to the camp between its founding in 1937 and its liberation in 1945. Deaths were due both to ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Martini, Frederic (2017)''Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences''

Published by Frederic H. Martini. . * Ydier, Francois (2016)

''The Boy and the Bomber''

Published by Mention the War Publications. . * Samuel, Wolfgang (2015)

''In Defense of Freedom: Stories of Courage and Sacrifice of World War II Army Air Forces Flyers''

Published by University Press of Mississippi. . . * Smith, Stephen (2015)

''From St Vith to Victory: 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron and the Campaign Against Nazi Germany''

Published by Pen and Sword Books Ltd, Barnsley England. * Walton, Marilyn and Eberhardt, Michael (2014)

''From Interrogation to Liberation''

Published by Author House. . . * Clutton-Brock, Oliver and Crompton, Raymond (2014)

''The Long Road''

Published by Grub Street Publishing, Havertown. . . * Gilbert, Adrian (2006)

''POW: Allied prisoners in Europe, 1939–1945''

Published John Murray, London. . . * Clutton-Brock, Oliver (2003)

''Footprints on the sands of time: RAF Bomber Command prisoners-of-war 1939–1945''

Published by Grub Street, London. . * Bard, Michael Geoffery (1996)

''Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler's Camps''

Published by Westview Press, Washington. . * Burney, Christopher (1946)

''The dungeon democracy''

Published by Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York.

External links

''Lost Airmen of Buchenwald''

A documentary film featuring Phil Lamason

''I Would Not Step Back...''

The Phil Lamason Project {{DEFAULTSORT:Lamason, Phil 1918 births 2012 deaths Buchenwald concentration camp survivors New Zealand military personnel of World War II New Zealand prisoners of war in World War II New Zealand World War II pilots Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) People from Dannevirke Royal Air Force officers Royal New Zealand Air Force personnel Shot-down aviators World War II prisoners of war held by Germany People from Napier, New Zealand People educated at Napier Boys' High School Massey University alumni Burials at Mangatera Cemetery