Petroleum Warfare Department on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Petroleum Warfare Department (PWD) was a government department established in Britain in 1940 in response to the invasion crisis during

At the beginning of World War II, in September 1939, little fighting occurred in the West until the German invasion of France and the

At the beginning of World War II, in September 1939, little fighting occurred in the West until the German invasion of France and the

A static flame trap allowed a length of road, typically , to be covered in flame and smoke at a moment's notice. The weapon was a simple arrangement of perforated pipes placed alongside a road. The pipes were steel, 1-2 inches (25-50 mm) in diameter and drilled with holes at angles carefully calculated to cover the road evenly. The perforated pipes were connected to larger pipes that led to a tank of fuel in a raised position. The fuel mixture was 25% petrol and 75%

A static flame trap allowed a length of road, typically , to be covered in flame and smoke at a moment's notice. The weapon was a simple arrangement of perforated pipes placed alongside a road. The pipes were steel, 1-2 inches (25-50 mm) in diameter and drilled with holes at angles carefully calculated to cover the road evenly. The perforated pipes were connected to larger pipes that led to a tank of fuel in a raised position. The fuel mixture was 25% petrol and 75%

The Petroleum Warfare Department soon received the assistance of Henry Newton and William Howard Livens, both known for designing mortars during the First World War.

During the First World War, Livens had developed a number of chemical-warfare and flame-throwing weapons. The largest of his works was the Livens large-gallery flame projector, which could project burning fuel . His best-known invention was the

The Petroleum Warfare Department soon received the assistance of Henry Newton and William Howard Livens, both known for designing mortars during the First World War.

During the First World War, Livens had developed a number of chemical-warfare and flame-throwing weapons. The largest of his works was the Livens large-gallery flame projector, which could project burning fuel . His best-known invention was the

A series of experiments investigated the possibility of burning the invader's barges before they could reach the English shore. The first idea was simply to explode a vessel filled with oil, and this was tried at Maplin Sands, where a Thames oil tanker, ''Suffolk'', with 50 tonnes of petroleum, was blown up in shallow water. Another idea developed was that the oil should be held in place on the water by a trough formed from

A series of experiments investigated the possibility of burning the invader's barges before they could reach the English shore. The first idea was simply to explode a vessel filled with oil, and this was tried at Maplin Sands, where a Thames oil tanker, ''Suffolk'', with 50 tonnes of petroleum, was blown up in shallow water. Another idea developed was that the oil should be held in place on the water by a trough formed from

Propaganda aside, the efforts of the PWD were real enough; they continued with experiments to actually set the sea on fire. Although initial tests were discouraging, Geoffrey Lloyd was reluctant to let the matter go. On 24 August 1940, on the northern shores of the

Propaganda aside, the efforts of the PWD were real enough; they continued with experiments to actually set the sea on fire. Although initial tests were discouraging, Geoffrey Lloyd was reluctant to let the matter go. On 24 August 1940, on the northern shores of the

The first British vehicle mounted flamethrower for regular army use was developed in 1940 by the then newly established PWD. This flamethrower was known as the ''Ronson'' after the cigarette lighter manufacturer of the same name known for its stylish and dependable cigarette lighter products. Fraser developed the Ronson from his original Cockatrice prototypes. The Ronson was mounted on a

The first British vehicle mounted flamethrower for regular army use was developed in 1940 by the then newly established PWD. This flamethrower was known as the ''Ronson'' after the cigarette lighter manufacturer of the same name known for its stylish and dependable cigarette lighter products. Fraser developed the Ronson from his original Cockatrice prototypes. The Ronson was mounted on a

By 1942 the PWD had developed the Ronson flamethrowers so that a range of was achieved. In September 1942, this improved appliance was put into production as the Wasp Mk I. An order for 1,000 was placed and all had been delivered by November 1943. The Wasp Mk I had two fuel tanks located inside the carrier's hull and used a large projector gun that was mounted over the top of the carrier. The Mk I was immediately outdated by the development of the Wasp Mk II which had a much handier flame projector mounted at the front on the machine-gun mounting. Although there was no improvement in range, this version performed much better being easier to aim and much safer to use.

The Wasp Mk II went into action during the

By 1942 the PWD had developed the Ronson flamethrowers so that a range of was achieved. In September 1942, this improved appliance was put into production as the Wasp Mk I. An order for 1,000 was placed and all had been delivered by November 1943. The Wasp Mk I had two fuel tanks located inside the carrier's hull and used a large projector gun that was mounted over the top of the carrier. The Mk I was immediately outdated by the development of the Wasp Mk II which had a much handier flame projector mounted at the front on the machine-gun mounting. Although there was no improvement in range, this version performed much better being easier to aim and much safer to use.

The Wasp Mk II went into action during the

George John Rackham, an ex-Tank Corps officer and tank designer who was a bus designer at

George John Rackham, an ex-Tank Corps officer and tank designer who was a bus designer at  Work began on two prototypes based on the

Work began on two prototypes based on the

The fuel-carrying trailer

The PWD worked on a flamethrower for the

The fuel-carrying trailer

The PWD worked on a flamethrower for the

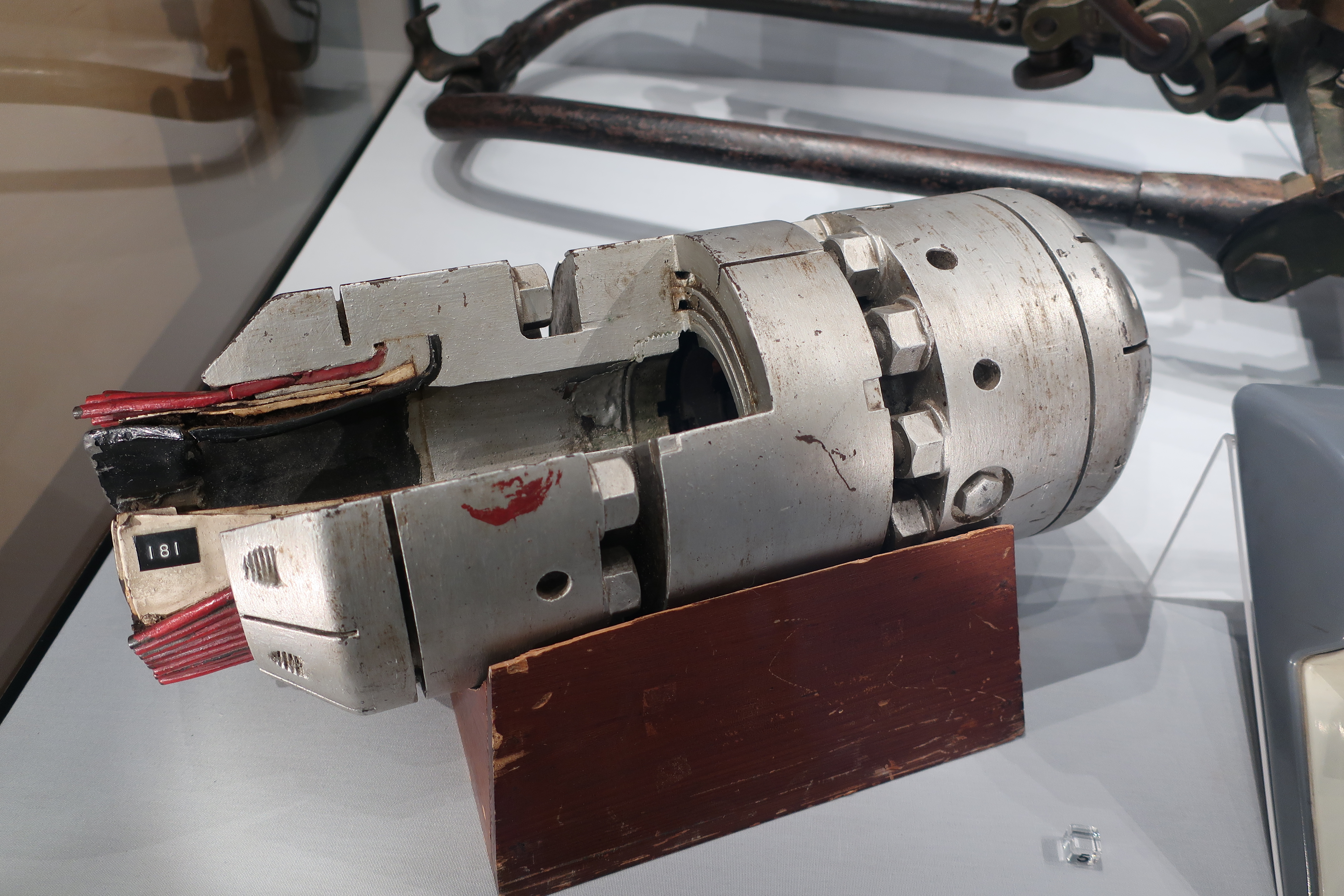

An all-steel pipe was also developed; this became known as HAMEL after Henry Alexander Hammick and B.J. Ellis of the

An all-steel pipe was also developed; this became known as HAMEL after Henry Alexander Hammick and B.J. Ellis of the

The invasion of Normandy began on 6 June 1944. Troops, equipment and vehicles were landed on the beaches and they were soon followed by thousands of jerrycans of fuel. 13,400 tons of fuel were landed this way on Dday itself.

Operation Pluto was scheduled to lay its first pipeline across the channel just 18 days after DDay, but this did not happen. Troops continued to be supported by transporting jerrycans of fuel. As daily fuel consumption rose, ship-to-shore pipelines codenamed TOMBOLA were laid.

The invasion of Normandy began on 6 June 1944. Troops, equipment and vehicles were landed on the beaches and they were soon followed by thousands of jerrycans of fuel. 13,400 tons of fuel were landed this way on Dday itself.

Operation Pluto was scheduled to lay its first pipeline across the channel just 18 days after DDay, but this did not happen. Troops continued to be supported by transporting jerrycans of fuel. As daily fuel consumption rose, ship-to-shore pipelines codenamed TOMBOLA were laid.

From the beginning of the war it became evident that many aircraft were being lost in accidents during landing in unfavourable weather. Fog was a particularly serious hazard, settling unpredictably over airfields where tired, possibly injured, pilots in aeroplanes short of fuel and in some cases damaged, had to land. The night of 16/17 October 1940 was particularly unfortunate. In raids by 73 bombers three aircraft were shot down but ten crashed on landing. When this was brought to the attention of Prime Minister Churchill he demanded that something be done: "... It ought to be possible to guide them down quite safely as commercial craft were before the war in spite of fog. Let me have full particulars. The accidents last night are very serious"

Previously Professor

From the beginning of the war it became evident that many aircraft were being lost in accidents during landing in unfavourable weather. Fog was a particularly serious hazard, settling unpredictably over airfields where tired, possibly injured, pilots in aeroplanes short of fuel and in some cases damaged, had to land. The night of 16/17 October 1940 was particularly unfortunate. In raids by 73 bombers three aircraft were shot down but ten crashed on landing. When this was brought to the attention of Prime Minister Churchill he demanded that something be done: "... It ought to be possible to guide them down quite safely as commercial craft were before the war in spite of fog. Let me have full particulars. The accidents last night are very serious"

Previously Professor

When the war in Europe was nearly won, the activities of the Petroleum Warfare Department were widely publicised as being demonstrative of British ingenuity.

When the war in Europe was nearly won, the activities of the Petroleum Warfare Department were widely publicised as being demonstrative of British ingenuity.

CAB 101/131

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, when Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

apparently would invade the country. The department was initially tasked with developing the uses of petroleum as a weapon of war, and it oversaw the introduction of a wide range of flame warfare weapons. Later in the war, the department was instrumental in the creation of the Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation

Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation (FIDO) (which was sometimes referred to as "Fog Intense Dispersal Operation" or "Fog, Intense Dispersal Of") was a system used for dispersing fog and pea soup fog (dense smog) from an airfield so that ai ...

(commonly known as FIDO) that cleared runways of fog

Fog is a visible aerosol consisting of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface. Reprint from Fog can be considered a type of low-lying cloud usually resembling stratus, and is heavily influ ...

allowing the landing of aircraft returning from bombing raids over Germany in poor visibility, and Operation Pluto

Operation Pluto (Pipeline Under the Ocean or Pipeline Underwater Transportation of Oil, also written Operation PLUTO) was an operation by British engineers, oil companies and the British Armed Forces to construct submarine oil pipelines un ...

, which installed prefabricated fuel pipelines between England and France soon after the Allied invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

in June 1944.

Inception

At the beginning of World War II, in September 1939, little fighting occurred in the West until the German invasion of France and the

At the beginning of World War II, in September 1939, little fighting occurred in the West until the German invasion of France and the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

in May 1940. Following the fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second World ...

and the withdrawal of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from the beaches at Dunkirk in June 1940, Britain was threatened with invasion by German armed forces in 1940 and 1941.

In response to this threat of invasion, the British sought to expand the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

, and Army, replace the equipment that had been left behind at Dunkirk, and supplement the regular armed services with volunteer organisations such as the part-time soldiers in the Home Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the American Civil War, starting w ...

. With many types of equipment in short supply, frantic efforts were made to develop new weapons – particularly those that did not require scarce materials.

Although oil imports from the Middle East had stopped and most oil for Britain came from the United States, no shortage of oil existed at the time; supplies originally intended for Europe were filling British storage facilities and full tankers were kept waiting in American ports. The amount of petrol allocated for civilian use was strictly rationed

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

and pleasure motoring was strongly discouraged. This was not, at least initially, because of a shortage of petrol, but because it might lead to large congregations of well-fuelled vehicles at popular places.

In the event of an invasion, the British would be faced with the problem of destroying these stocks lest they should prove of use to the enemy (as they had in France). By mid-June, as a basic anti-invasion precaution, wayside petrol stations

A filling station, also known as a gas station () or petrol station (), is a facility that sells fuel and engine lubricants for motor vehicles. The most common fuels sold in the 2010s were gasoline (or petrol) and diesel fuel.

Gasolin ...

near the coast had been emptied, or at least had their pumps disabled, and garages everywhere were required to have a plan to prevent their stocks being of use to the invader.

On 29 May 1940, as the evacuation of the BEF was in progress, Maurice Hankey

Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey, 1st Baron Hankey, (1 April 1877 – 26 January 1963) was a British civil servant who gained prominence as the first Cabinet Secretary and later made the rare transition from the civil service to ministerial office. ...

, then a cabinet minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

, joined the Ministerial Committee on Civil Defence (CDC) chaired by Sir John Anderson

John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley, (8 July 1882 – 4 January 1958) was a Scottish civil servant and politician who is best known for his service in the War Cabinet during the Second World War, for which he was nicknamed the "Home Front P ...

, the Secretary of State for the Home Office and Home Security

Home security includes both the security hardware placed on a property and individuals' personal security practices. Security hardware includes doors, locks, alarm systems, lighting, motion detectors, and security camera systems. Personal se ...

. Among many ideas, Hankey "brought out of his stable a hobby horse, which he had ridden very hard in the 1914–18 war – namely the use of burning oil for defensive purposes." Hankey believed that oil should not just be denied to an invader, but used to impede him. Towards the end of June, Hankey brought his scheme up at a meeting of the Oil Control Board and produced for Commander-in-Chief Home Forces Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside (30 November 1016; , ; sometimes also known as Edmund II) was King of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. He was the son of King Æthelred the Unready and his first wife, Ælfgifu of York. Edmund's reign was marred by ...

extracts of his paper on experiments with oil in the First World War. On 5 June, Churchill authorised Geoffrey Lloyd, the Secretary for Petroleum

The position of Secretary for Petroleum is a now defunct office in the United Kingdom Government, associated with the Board of Trade.

In 1929, the Secretary for Mines (now also defunct) took over responsibility for petroleum.

In 1939 the Petroleu ...

, to press ahead with experiments, with Hankey taking the matter under his general supervision.

Donald Banks

Donald Banks had served with distinction in World War I, winning theDistinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, ty ...

and Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC ...

. He joined the civil service, and in 1934, he was made Director-General of the Post Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional se ...

, he then moved to the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

and served there as Permanent Under Secretary from 1936 to 1938. Due to overwork, Banks was given lighter duties, including a mission to Australia to advise on aircraft production and a job at the Import Duties Advisory Committee. During this period, Banks was in the Territorial Army Reserve. When hostilities broke out in September 1939, the advisory committee was abolished and he was free to serve in the armed forces.

Banks was soon posted as air attaché

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for ...

to the quartermaster general of 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division

The 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army that saw distinguished service in the Second World War. Pre-war, the division was part of the Territorial Army (TA) and the two ''Ts'' in the divisional in ...

– a first-line division of the Territorial Army. Banks got on well with his commander, Major-general Giffard LeQuesne Martel

Lieutenant-General Sir Giffard Le Quesne Martel (10 October 1889 – 3 September 1958) was a British Army officer who served in both the First and Second World Wars. Familiarly known as "Q Martel" or just "Q", he was a pioneering British milita ...

. Banks admired his leadership and his enthusiasm for experimentation and improvisation. In October 1939, the division was sent to the Cotswold

The Cotswolds (, ) is a region in central-southwest England, along a range of rolling hills that rise from the meadows of the upper Thames to an escarpment above the Severn Valley and Evesham Vale.

The area is defined by the bedrock of Jur ...

s, and in January 1940, it was moved to France.

When Germany attacked in May, the division was heavily involved in the fighting around Arras and was later withdrawn to the coast. Banks later recalled looking out to sea from a clifftop and seeing "an awe-inspiring sight ..A few miles away an oil tanker had been bombed or had struck a mine. Masses of the blackest smoke pillared up into a gigantic pall in the sky while in the vast lake of fire, spreading it seemed for miles on the water a flame blazed and leapt like an angry volcano ..I was often to recall that scene in subsequent days of Flame Warfare". The division was evacuated to England.

Early in July 1940, Banks was summoned to the presence of Geoffrey Lloyd, who explained the vision that Hankey and he shared: "Flame all across Britain" he said, "ringing the coasts, spurting from the hedges and rolling down the hills. We will burn the invader back into the sea."

Considering Lloyd's ideas over the next few days and consulting with other soldiers, Banks found both professional scepticism and enthusiasm. Banks, a man who said he preferred the prospect of real fighting over "Whitehall warfare", was not himself keen and his first instinct was to suggest that petroleum weapons should be developed locally. Lloyd would have none of it and Banks was ordered to report to him for special duties. On 9 July, cutting through red tape, the Petroleum Warfare Department was created.

The Petroleum Warfare Department started on 9 July 1940 in three small rooms. They were independently administered and financed with a few staff entirely lacking in technical knowledge.

Flame traps

PWD took inspiration from events that happened during the retreat to Dunkirk in June 1940. One example occurred whenBoulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

was attacked in the early hours of 23 May and the road to Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

was cut. In the defence of Boulogne, a group of pioneers under Lieutenant-colonel Donald Dean

Donald Dean (born June 21, 1937) is a jazz drummer who has worked with Kenny Dorham, Les McCann and others. A collection related to him is led by the ''Los Angeles Jazz Institute.''

He appears, alongside Les McCann and Eddie Harris, on the soul ...

, had improvised a road block made of vehicles and piles of furniture from bombed-out houses. An approaching tank began to push its way over the obstruction, as Dean wrote:

The newly formed department quickly made arrangements for some practical experiments at Dumpton Gap

Broadstairs is a coastal town on the Isle of Thanet in the Thanet district of east Kent, England, about east of London. It is part of the civil parish of Broadstairs and St Peter's, which includes St Peter's, and had a population in 2011 of ...

in Kent. These were the source of some excitement for witnesses, who included the pilots of enemy planes. Many of the first ideas to be tried proved fruitless, but experience quickly led to the development of the first practical weapon - the static flame trap.

Static flame trap

A static flame trap allowed a length of road, typically , to be covered in flame and smoke at a moment's notice. The weapon was a simple arrangement of perforated pipes placed alongside a road. The pipes were steel, 1-2 inches (25-50 mm) in diameter and drilled with holes at angles carefully calculated to cover the road evenly. The perforated pipes were connected to larger pipes that led to a tank of fuel in a raised position. The fuel mixture was 25% petrol and 75%

A static flame trap allowed a length of road, typically , to be covered in flame and smoke at a moment's notice. The weapon was a simple arrangement of perforated pipes placed alongside a road. The pipes were steel, 1-2 inches (25-50 mm) in diameter and drilled with holes at angles carefully calculated to cover the road evenly. The perforated pipes were connected to larger pipes that led to a tank of fuel in a raised position. The fuel mixture was 25% petrol and 75% gas-oil

''Gas-Oil'' is a 1955 French crime drama film directed by Gilles Grangier and starring Jean Gabin, Jeanne Moreau, Gaby Basset and Ginette Leclerc. It was shot at the Epinay Studios in Paris and on location at a variety of places. The film's set ...

that was contrived to be of no use as motor vehicle fuel should it be captured. All that was required to trigger the weapon was to open a valve and for a Home Guard to throw in a Molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with fla ...

creating an inferno. The ideal location for the trap was a place where vehicles could not easily escape, such as a steep-sided sunken road

A sunken lane (also hollow way or holloway) is a road or track that is significantly lower than the land on either side, not formed by the (recent) engineering of a road cutting but possibly of much greater age.

Various mechanisms have been pro ...

. Some trouble was taken with camouflage; pipes could be hidden in gutters or disguised as handrails; others were simply left as innocent-looking plumbing.

All the required pipes and valves could be obtained from the gas and water industries with little modification required beyond drilling a few holes. In general, gravity was all that was required to provide sufficient pressure for the fountains of oil but, where necessary, pumps were provided.

Later versions were a little more sophisticated; remote ignition could be achieved in a variety of ways. In one system, called the Birch Igniter, the pressure of the oil at the end of the pipe would squeeze glycerine

Glycerol (), also called glycerine in British English and glycerin in American English, is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is sweet-tasting and non-toxic. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids know ...

from a rubber bulb; the glycerine would fall onto a container of potassium permanganate

Potassium permanganate is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula KMnO4. It is a purplish-black crystalline salt, that dissolves in water as K+ and , an intensely pink to purple solution.

Potassium permanganate is widely used in the c ...

, which would then ignite spontaneously. Another method was to run a pair of small rubber tubes, down one of which would be passed acetylene

Acetylene ( systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pure ...

and the other chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

; when, at the far end, these two gases were allowed to mix, there would be a spontaneous ignition. This system had the advantage that it could be turned on and off repeatedly. The development of the flame fougasse

A flame fougasse (sometimes contracted to fougasse and may be spelled foo gas) is a type of mine or improvised explosive device which uses an explosive charge to project burning liquid onto a target. The flame fougasse was developed by the P ...

(see below) provided a method of remote electrical ignition that could only be used once, but was virtually instantaneous.

Some 200 static flame traps were installed, mainly by the employees of oil companies whose services were placed at the disposal of the government.

Mobile flame traps

In addition to the static flame traps, mobile units were created. The main design used an otherwise redundant tank mounted on the back of a 30 cwt lorry, just behind the cabin. In the middle of the remaining space was a petrol-driven pump and either side of this was stored of armoured rubber hose. Two nozzles were provided with a primitive sight and with spikes for pushing into the ground. Gas tubes for chlorine and acetylene gas were provided for ignition. The resulting jets of flame had a range of . Because a shortage of pumps existed – they were badly needed for fighting fires started by bombing – a simpler type of mobile flame trap was also designed. This consisted of a number of diameter pipes welded shut to make a long cylindrical drum, which was filled with of petrol-oil mixture and pressurised with an inert gas. Five of these cylinders could be transported on the back of a vehicle, and at a weight just under , could be deployed reasonably quickly wherever an ambush was required. The cylinders would be placed at intervals along a road, each with a short length of hose leading to a nozzle secured by ground spikes. Flow was initiated by a pull string that opened a valve and ignition was provided by Molotov cocktails.Flame fougasse

The Petroleum Warfare Department soon received the assistance of Henry Newton and William Howard Livens, both known for designing mortars during the First World War.

During the First World War, Livens had developed a number of chemical-warfare and flame-throwing weapons. The largest of his works was the Livens large-gallery flame projector, which could project burning fuel . His best-known invention was the

The Petroleum Warfare Department soon received the assistance of Henry Newton and William Howard Livens, both known for designing mortars during the First World War.

During the First World War, Livens had developed a number of chemical-warfare and flame-throwing weapons. The largest of his works was the Livens large-gallery flame projector, which could project burning fuel . His best-known invention was the Livens projector

The Livens Projector was a simple mortar-like weapon that could throw large drums filled with flammable or toxic chemicals.

In the First World War, the Livens Projector became the standard means of delivering gas attacks by the British Army an ...

: a simple mortar that could throw a projectile containing about of explosives, incendiary oil, or most commonly, poisonous phosgene

Phosgene is the organic chemical compound with the formula COCl2. It is a toxic, colorless gas; in low concentrations, its musty odor resembles that of freshly cut hay or grass. Phosgene is a valued and important industrial building block, esp ...

gas. The great advantage of the Livens projector was that it was cheap; this allowed hundreds, and on occasions thousands, to be set up and then fired simultaneously, catching the enemy by surprise. Both Livens and Newton experimented with field-expedient versions of the Livens projector using commercially available five-gallon drums and tubes. Newton experimented with firing milk bottles filled with phosphorus using a rifle. None of these experiments were taken forward.

However, one of Livens' PWD demonstrations, probably first seen about mid-July at Dumpton Gap, was more promising. A barrel of oil was simply blown up on the beach; Lloyd was said to have been particularly impressed when he observed a party of high-ranking officers witnessing a test from the top of a cliff making "an instantaneous and precipitate movement to the rear". The work was dangerous. Livens and Banks were experimenting with five-gallon drums in the shingle at Hythe

Hythe, from Anglo-Saxon ''hȳð'', may refer to a landing-place, port or haven, either as an element in a toponym, such as Rotherhithe in London, or to:

Places Australia

* Hythe, Tasmania

Canada

*Hythe, Alberta, a village in Canada

England

* ...

when a short circuit

A short circuit (sometimes abbreviated to short or s/c) is an electrical circuit that allows a current to travel along an unintended path with no or very low electrical impedance. This results in an excessive current flowing through the circu ...

triggered several weapons. By good fortune, the battery of drums where the party was standing failed to go off.

The experiments led to a particularly promising arrangement - a 40-gallon steel drum

The steelpan (also known as a pan, steel drum, and sometimes, collectively with other musicians, as a steelband or steel orchestra) is a musical instrument originating in Trinidad and Tobago. Steelpan musicians are called pannists.

Descript ...

buried in an earthen bank with just the round front end exposed. At the back of the drum was an explosive which, when triggered, ruptured the drum and shot a jet of flame about wide and long. The design was reminiscent of a weapon dating from late medieval times called a fougasse - a hollow in which was placed a barrel of gunpowder covered by rocks, the explosives to be detonated by a fuse at an opportune moment. Livens' new weapon was duly dubbed the flame fougasse. The flame fougasse was demonstrated to Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

(Lord Privy Seal), Maurice Hankey

Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey, 1st Baron Hankey, (1 April 1877 – 26 January 1963) was a British civil servant who gained prominence as the first Cabinet Secretary and later made the rare transition from the civil service to ministerial office. ...

, and General Liardet (GOC 56th Division) on 20 July 1940.

A variant of the flame fougasse called the "demi-gass" was a fougasse barrel placed horizontally in the open with an explosive charge underneath that would rupture the barrel and flip it over towards the target. Another variant was the "hedge hopper", a fougasse barrel on its end with an explosive charge underneath that would send it bounding over a hedge or wall; this made the hedge hopper particularly easy to conceal. A further variant of the hedge hopper idea was devised for St Margaret's Bay, where the barrels would be sent rolling over the cliff edge.

In all, some 50,000 flame fougasse barrels were distributed, of which the great majority were installed in one of 7,000 batteries mostly in southern England and a little later at 2,000 sites in Scotland. Some barrels were held in reserve, while others were deployed at storage sites to destroy fuel depots at short notice. The size of a battery varied from just one drum to as many as 14; a four-barrel battery was the most common installation and the recommended minimum. Where possible, half the barrels in a battery were to contain the 40/60 mixture and half the sticky 5B mixture.

Troubled waters

Operation Lucid

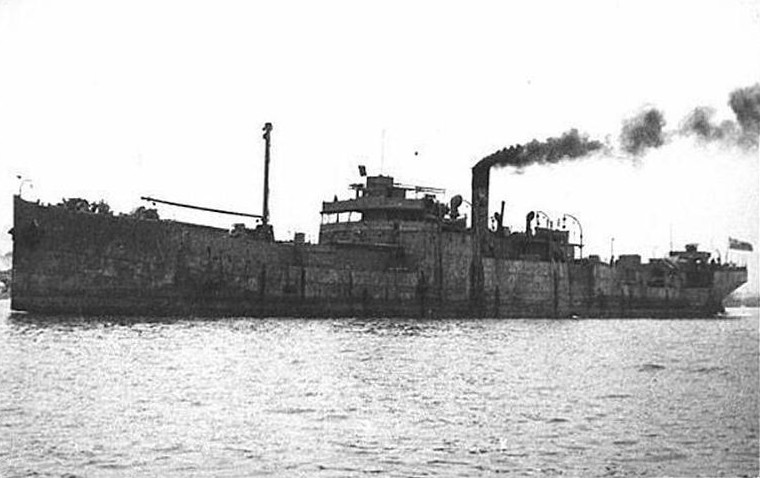

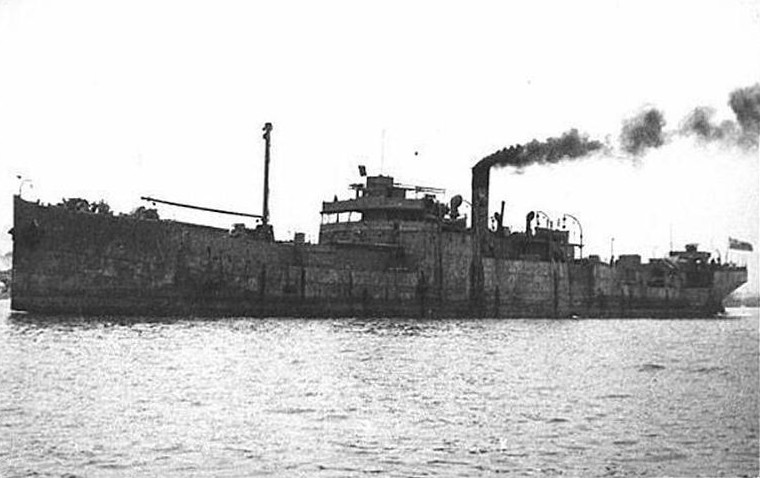

A series of experiments investigated the possibility of burning the invader's barges before they could reach the English shore. The first idea was simply to explode a vessel filled with oil, and this was tried at Maplin Sands, where a Thames oil tanker, ''Suffolk'', with 50 tonnes of petroleum, was blown up in shallow water. Another idea developed was that the oil should be held in place on the water by a trough formed from

A series of experiments investigated the possibility of burning the invader's barges before they could reach the English shore. The first idea was simply to explode a vessel filled with oil, and this was tried at Maplin Sands, where a Thames oil tanker, ''Suffolk'', with 50 tonnes of petroleum, was blown up in shallow water. Another idea developed was that the oil should be held in place on the water by a trough formed from coir

Coir (), also called coconut fibre, is a natural fibre extracted from the outer husk of coconut and used in products such as floor mats, doormats, brushes, and mattresses. Coir is the fibrous material found between the hard, internal shell an ...

matting. A machine formed the trough from a flat mat as it was paid out over the stern of a ship. Trials with the ''Ben Hann'' produced a flaming ribbon 880 yards long and 6 feet wide (800 m × 2 m) that could be towed at four knots. Neither of these experiments were carried forward to produce workable defences.

The ''Suffolk'' did, however, provide a trial run for an even more ambitious idea - the invasion barges would be burned even before they left port. The plan was first floated in early June/July 1940 and became known as Operation Lucid

Operation Lucid was a British plan to use fire ships to attack invasion barges that were gathering in ports on the northern coast of France in preparation for a German invasion of Britain in 1940. The attack was initiated several times in Sept ...

.

Three old tankers were quickly prepared as fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

s for the operation under the command of Augustus Agar

Commodore Augustus Willington Shelton Agar, (4 January 1890 – 30 December 1968) was a Royal Navy officer in both the First and the Second World Wars. He was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the ...

VC with Morgan Morgan-Giles

Rear-Admiral Sir Morgan Charles Morgan-Giles, (19 June 1914 – 4 May 2013) was a Royal Navy officer, decorated during the Second World War, who later served as a Conservative Member of Parliament. At the time of his death, he was the oldest li ...

as his staff officer. Each ship was laden with over 2,000 tons of flammable oils and a miscellany of leftover explosive devices. Although the operation was started several times in September–October 1940, the attempts were thwarted by bad weather, unreliable ships, and finally, one of the destroyers in the group was damaged by a mine. By November, any invasion plan had been called off and Lucid was shelved.

Burning seas

From its earliest days, the PWD experimented with "setting the sea on fire" by burning oil that was floating on the surface. It was immediately appreciated that the possibilities of such a weapon lay not only in its ability to destroy the enemy, but also in the propaganda value of the terror of fire. In 1938, an Enemy Publicity Section, created for propaganda to be sent to the enemy, was formed by Hankey and a new section was formed under Sir Campbell Stuart, who was a former editor of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' newspaper. Being allocated premises at Electra House

Electra House is a building at 84 Moorgate, London, England. It is notable as the wartime London base of Cable & Wireless Limited, and office of Department EH — one of the three British organisations that merged in World War II to form the Spe ...

, the new section was dubbed Department EH. During the Munich crisis

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Ger ...

of 1938, a number of leaflets were printed with the intention of dropping them over Germany. The leaflet drop never took place, but the exercise prompted Department EH to issue a note to the Air Ministry insisting on the importance of a properly coordinated system for sending information to enemy countries. The Permanent Secretary

A permanent secretary (also known as a principal secretary) is the most senior civil servant of a department or ministry charged with running the department or ministry's day-to-day activities. Permanent secretaries are the non-political civil ...

(most senior civil servant of a department) at the Air Ministry to whom the note was addressed was Sir Donald Banks, who would later head the PWD.

On 25 September 1939, Department EH was mobilised to Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

where it joined another subversion team known as Section D that had been formed by Major Laurence Grand.

In July 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

invited Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 19 ...

to take charge of the newly formed Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its p ...

(SOE). The mission of the SOE was to encourage and facilitate espionage and sabotage behind enemy lines, or as Churchill put, it: to "set Europe ablaze". Among those present at the first summit meeting of SOE on 1 July 1940 were Lord Hankey, Geoffrey Lloyd and Desmond Morton – people who would be instrumental in the formation of the PWD just a few days later.

Department EH and section D later became SO1 and SO2 of the SOE. Subsequently, in September 1941, responsibilities for political warfare was taken away from the SOE with the formation of the Political Warfare Executive

During World War II, the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) was a British clandestine body created to produce and disseminate both white and black propaganda, with the aim of damaging enemy morale and sustaining the morale of countries occupied ...

.

Although PWD would go on to work on burning floating oil, a plan was hatched to spread the story that such a weapon already existed even before the first trials were performed. Writer James Hayward has made an extensive study of this curious story; in ''The Bodies on the Beach'', Hayward makes a compelling case for the view that the burning seas work was driven substantially by the needs of propaganda and was a sophisticated bluff that became Britain's first major propaganda success of the war. Writing just after the war, Banks said, "Perhaps the greatest contribution from all these variegated efforts was in building up the great propaganda story of the Flame Defence of Britain which swept the Continent of Europe in 1940."

The details of the story indicated the invention of a bomb that would spread a thin film of volatile liquid on the surface of the water and then ignite it. This rumour was whispered into attentive ears in neutral cities such as Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

, Lisbon, Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

, Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

, New York, and other places, probably around late July or early August 1940. The burning-seas rumour appealed to the dark imaginations of both friend and foe. Soon, interrogation of captured Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

pilots revealed that the rumour had become common knowledge.

German armed forces began experimenting with burning floating oil. On 18 August, they ignited 100 tons of floating oil; it burned for 20 minutes producing heat and copious smoke – this was almost a week before the first successful British ignition.

In Europe, the burning-seas story became embellished to the point where the story included a German invasion attempt thwarted by the ignition of oil on water. American war correspondent William Lawrence Shirer was based in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

at the time, but in mid-September, he visited Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, Switzerland.

On the evening of the following day, Shirer arrived back in Berlin:

The following day, Shirer heard about further train loads of wounded soldiers. A plausible explanation for these wounded is that they were hurt in RAF bombing raids on ports of embarkation. Such raids were certainly going on, though it seems they were generally fairly ineffective and no records of significant German casualties have been turned up. It seems likely that the rumour machine inflated light casualties to proportions of strategic consequence.

The British were getting better organised. A system was set up to collect suggestions for Inspired Rumours; these suggestions, which became known as ''SIBS'' (from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

''sibilare'', to hiss). SIBS, were sifted through at weekly meetings in order that they should present a consistent message and to ensure that ludicrously improbable and inadvertently true rumours were filtered out. New SIBS included "small scale attempts at invasion have been made and have been beaten off with devastating losses. In fact none are alive to tell. Thousands of floating German corpses have been washed ashore." and "The fishing populations of the west coast of Denmark and the south coast of Norway are selling fish but they won’t eat them. The reason is that there are numbers of German corpses on which the fish feed. There have even been cases of shreds of clothing and buttons, etc. being found inside the fish."

The story of the burning seas was further reinforced. In October, the RAF dropped leaflets containing handy phrases for visitors to the United Kingdom in German, French, and Dutch. The phrases included "the sea smells of petrol here", "the sea even burns here", "see how well the captain burns", "Karl/Willi/Fritz/Johann/Abraham: cremated/drowned/minced by the propellers!" As Hayward explains, these leaflets were simply building on and reinforcing the rumours of a failed invasion attempt that were being disseminated around the world from late September. The original propaganda was conflated with other events both real and imaginary and the rumours spread. Of course, the German command knew that the stories were untrue; the real targets of the propaganda were the men who might actually be asked to attempt a landing in England. Berlin felt forced officially to deny the rumours:

Inevitably, the story made its way back to the UK. Publication of the contents of propaganda leaflets dropped by the RAF was not permitted and other stories such as an official statement from the Free French Information Service through the Ministry of Information saying that "30,000 Germans drowning in an attempted embarkation last September" were suppressed. Vivid and plausible accounts of a thwarted invasion were published in American newspapers and the rumours spread in Britain and proved persistent. Questions were even asked in parliament. Writing just after the war, the Chief Press Censor, Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

George Pirie Thomson said that "... in the whole course of the war there was no story which gave me so much trouble as this one of the attempted German invasion, flaming oil on the water and 30,000 burned Germans."

On 7 September 1940, the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

was still raging, but the German Air Force () changed its tactics and started to bomb London. With the accumulation of invasion barges and favourable tides, the authorities were convinced that invasion was imminent, the codeword ''Cromwell'' was passed to the Army and Home Forces. The codeword was only meant to indicate "invasion imminent", but with a nation tense with expectation and some Home Guardsmen incompletely briefed, some believed that the invasion had started and this caused great confusion. In some areas, church bells were rung on receipt of the codeword even though this was only supposed to happen when invaders were in the immediate area. Roadblocks were set up, some bridges blown, and land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s sown on some roads (killing three Guards officers). Home Guard units searched beaches for invasion barges and scanned the skies for approaching German paratroopers, but none came. Public recollection of these events did much to reinforce the idea that some kind of landing had, in fact, been attempted.

The burning sea lie provided the British with their first major black propaganda

Black propaganda is a form of propaganda intended to create the impression that it was created by those it is supposed to discredit. Black propaganda contrasts with gray propaganda, which does not identify its source, as well as white propagand ...

victory. The compelling story is likely to be the basis of a number of invasion myths that remained in circulation throughout the remainder of the 20th century, that the Germans attempted an invasion which was thwarted by the use of sea-burning bombs. The most persistent of these stories becoming known as the Shingle Street Mystery named after an isolated village on the Suffolk coast.

Flame barrage

Propaganda aside, the efforts of the PWD were real enough; they continued with experiments to actually set the sea on fire. Although initial tests were discouraging, Geoffrey Lloyd was reluctant to let the matter go. On 24 August 1940, on the northern shores of the

Propaganda aside, the efforts of the PWD were real enough; they continued with experiments to actually set the sea on fire. Although initial tests were discouraging, Geoffrey Lloyd was reluctant to let the matter go. On 24 August 1940, on the northern shores of the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay t ...

, near Titchfield

Titchfield is a village in southern Hampshire, by the River Meon. The village has a history stretching back to the 6th century. During the medieval period, the village operated a small port and market. Near to the village are the ruins of Titc ...

, 10 tanker wagons began to pump oil down pipes running from the top of a 30-foot-high (10 m) cliff down into the water at the rate of about 12 tons/hour. In front of many spectators, the oil was ignited by flares and a system of sodium and petrol pellets. In a matter of seconds, a raging wall of flame was produced; the intense heat caused the water to boil and people at the cliff edge were obliged to retreat. The demonstration was very dramatic, but it was not an unqualified success because the circumstances were improbably favourable; in the sheltered waters of the Solent, the sun-warmed sea was calm and the winds light. A lengthy series of experiments continued with many reverses; in one case, the pipes attached to "Admiralty scaffolding

Admiralty scaffolding, also known as Obstacle Z.1 or sometimes simply given as beach scaffolding or anti-tank scaffolding, was a British design of anti-tank and anti-boat obstacle made of tubular steel. It was widely deployed on beaches of ...

"' (an antitank barrier of scaffolding placed in the shallows) were torn up in a storm and in another incident sappers

A sapper, also called a pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, preparing fie ...

were blown up by beach mines. It was found that effectiveness was very much affected by sea conditions; a low temperature made ignition more difficult and waves would quickly break up the oil into small ineffectual slicks.

On 20 December 1940, Generals Harold Alexander and Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence an ...

and many other senior officers gathered for a demonstration. The performance was completely unconvincing with just a few small pools of burning oil battered by the surf. The cold, cloudy weather matched the mood of pessimism; Banks describes this day as the Black Friday in the annals of the PWD.

General Alexander was sympathetic to the PWD's problems, and suggested that the pipes be moved to a point immediately above the high tide point and, after several months of further work, this proved to be the solution – oil sprayed and burnt over rather than on the water. On 24 February 1941, the Chiefs of Staff committee, that included General Brooke, watched films of the recent experiments and approved the installation of 50 miles of flame barrage - 25 miles on the south-eastern coast, 15 miles on the eastern, and 10 miles on the southern commands.

Although Geoffrey Lloyd, Secretary for Petroleum, was enthusiastic, General Brooke was, on reflection, not convinced of its efficacy. Brooke's main objections were that the weapon was dependent upon favourable winds, it created a smokescreen that might favour the enemy, and it was very vulnerable to bombing and shell fire; in any case, it was of short duration. The required resources were considerable and a serious shortage of materials existed; lack of support from authorities and the competing demands for supplies meant that the plans were cut back to thirty miles of barrage, then fifteen and then less than ten miles. According to Banks: "Lengths of this flame defence ultimately were completed at Deal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, a ...

between Kingsdown and Sandwich

A sandwich is a food typically consisting of vegetables, sliced cheese or meat, placed on or between slices of bread, or more generally any dish wherein bread serves as a container or wrapper for another food type. The sandwich began as a po ...

, at St. Margaret's Bay, at Shakespeare Cliff near Dover railway tunnel, at Rye where a remarkable system of remote control across the marshes was installed, and at Studland Bay

Studland is a village and civil parish on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset, England. The village is located about north of the town of Swanage, over a steep chalk ridge, and south of the South East Dorset conurbation at Sandbanks, from which it i ...

. In South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

long stretches were put in hand at the time when the airborne threat to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

was looming large, and sections at Wick

Wick most often refers to:

* Capillary action ("wicking")

** Candle wick, the cord used in a candle or oil lamp

** Solder wick, a copper-braided wire used to desolder electronic contacts

Wick or WICK may also refer to:

Places and placename ...

and Thurso

Thurso (pronounced ; sco, Thursa, gd, Inbhir Theòrsa ) is a town and former burgh on the north coast of the Highland council area of Scotland. Situated in the historical County of Caithness, it is the northernmost town on the island of Gr ...

, but these were not brought to completion. In Cornwall at Porthcurno

Porthcurno ( kw, Porthkornow, Porthcornow, meaning ''"pinnacle cove"'', see below) is a small village covering a small valley and beach on the south coast of Cornwall, England in the United Kingdom. It is the main settlement in a civil and an e ...

, where the important transatlantic cables came ashore, a gravity fed section was put in as a security measure against raids."

Portable flamethrowers

DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the British had developed flamethrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in World ...

s. Banks had seen the Livens large-gallery flame projector used at the Somme in July 1916 and a large-scale flamethrower had been installed on HMS ''Vindictive'' and used in the raid on Zeebrugge. Portable flame-throwing apparatus was also designed, but the war ended before it could be fully employed; further development ceased and records of the work were lost.

Work restarted in 1939 at the newly formed Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for airc ...

Research Department at Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained thr ...

, and many of the basic technical problems were investigated such as the design of valves and nozzles, the problem of ignition, and of fuels and propellants. Independently, Commander Marsden was working on portable flamethrowers for the Army. His work eventually resulted in the semiportable "Harvey" flamethrower and the backpack "Marsden" flamethrower. Meanwhile, the PWD developed the Home Guard flamethrower as a quickly extemporised weapon.

Home Guard flamethrower

The so-called Home Guard flamethrower was not a flamethrower in the conventional sense, but a small, semimobile flame trap. From about September 1940, 300 Home Guard units received a kit of parts provided by the PWD - a barrel, of hose, a hand pump, some connective plumbing, and a set of do-it-yourself instructions. The barrel was set upon an hand cart that was made locally from four-by-two-inch timber and mounted on a pair of wheels salvaged from a car axle. The nozzle and ground spike were of simple construction from sections of three-quarter-inch-diameter gas pipe with a used food can over the end to catch drips of fuel that would maintain a flame when the pressure was allowed to drop. When completed, the weapon was filled with a 40/60 mixture obtained locally. The Home Guard flamethrower was light enough to be wheeled along roads and possibly over fields to where it was needed by its crew of five or six men. It would be used as part of an ambush in combination with Molotov cocktails and whatever other weapons were available. The pump was operated by hand and would give a flame of up to in length, but only for about two minutes of continuous operation.Harvey flamethrower

The Harvey flamethrower was introduced in August 1940, and was mostly made from readily available parts such as wheels from agricultural equipment manufacturers and commercially available compressed air cylinders. It comprised a welded-steel cylinder containing 22 gallons (100 L) ofcreosote

Creosote is a category of carbonaceous chemicals formed by the distillation of various tars and pyrolysis of plant-derived material, such as wood or fossil fuel. They are typically used as preservatives or antiseptics.

Some creosote types were ...

and a standard bottle of compressed nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

at mounted on a sack truck :''"Hand truck" may also refer to Pallet jack.''

A hand truck, also known as a hand trolley, dolly, stack truck, trundler, box cart, sack barrow, cart, sack truck, two wheeler, or bag barrow, is an L-shaped box-moving handcart with handles at one ...

of the type that a railway-station porter might use. About of armoured hose provided the connection to a lance with a nozzle and some paraffin-soaked cotton waste that was set alight to provide a source of ignition. In operation, the pressure in the fuel container was raised to about , causing a cork in the nozzle to be ejected followed by a jet of fuel lasting about 10 seconds at a range up to . Like the Home Guard flamethrower, it was intended as an ambush weapon, but in this case the operator was able to direct the flames by moving the lance which would be pushed through a hole in otherwise bulletproof cover such as a brick wall.

Marsden flamethrower

The Marsden flamethrower, probably introduced about June 1941, comprised a backpack with of fuel pressurised to by compressed nitrogen gas; the backpack was connected to a "gun" by means of a flexible tube, and the weapon was operated by a simple lever. The weapon could give 12 seconds of flame divided into any number of individual spurts. The Marsden flamethrower was heavy and cumbersome; 1500 were made but few were issued. Neither the Harvey nor the Marsden was popular with the Army; both ended up with the Home Guard. The Marsden was superseded in 1943 by theFlamethrower, Portable, No 2

The Flamethrower, Portable, No 2 (nicknamed ''Lifebuoy'' from the shape of its fuel tank), also known as the ''Ack Pack'', was a British design of flamethrower for infantry use in the Second World War.

Description

It was a near copy of the Germ ...

which became known as the "lifebuoy" flamethrower from the ring shape of the fuel tank.

Vehicle-mounted flamethrowers

Cockatrice

The PWD brought together and supervised a number of otherwise independent developments of vehicle-mounted flamethrowers. The first product of this work was a prototype of Cockatrice that was demonstrated in August 1940. Reginald Fraser ofImperial College

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, London University

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degre ...

, who was also a director of the Lagonda car company, developed an annular flamethrower, that threw petrol with an outer layer of thickened fuel. He thought that this would reduce the risk of fire working backwards to the fuel tank because oxygen would not be present. With the encouragement of the PWD, Fraser produced and demonstrated a prototype at Snoddington Furze in August 1940. Fraser went on to have an experimental vehicle put together by Lagonda on a Commer

Commer was a British manufacturer of commercial and military vehicles from 1905 until 1979. Commer vehicles included car-derived vans, light vans, medium to heavy commercial trucks, and buses. The company also designed and built some of its own ...

lorry chassis. A demonstration of the Lagonda vehicle at PWD's test site at Moody Down farm near Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

was attended by Nevil Shute Norway and Lieutenant Jack Cooke of the Admiralty Directorate of Miscellaneous Weapons Development

Directorate may refer to:

Contemporary

*Directorates of the Scottish Government

* Directorate-General, a type of specialised administrative body in the European Union

* Directorate-General for External Security, the French external intelligence a ...

. Norway later recalled, "It was a terrifying apparatus ... tfired a mixture of diesel oil and tar and had a range of about 100 yards. It had a flame 30 feet in diameter and used 8 gallons of fuel a second ... When demonstrated to admirals and generals, it usually appalled and horrified them ..."

Norway understood that invading airborne troops landing at an airfield would need about one minute after touchdown while they prepared their equipment, in which time they would be extremely vulnerable; a flamethrower on a vehicle that could be driven at speed could envelop the enemy in fire before the vehicle itself was destroyed. Cooke worked on the problem and the result was "Cockatrice". This device had a rotating weapon mount with elevation to 90° and a range around , stored about two tons of fuel and used compressed carbon monoxide as a propellant. The ''Light Cockatrices'' variant was based on an armoured Bedford QL

The Bedford QL was a series of trucks, manufactured by Bedford for use by the British Armed Forces in the Second World War.

History

At the outbreak of WW II, Bedford was contracted by the British War Office to produce a 3 ton 4×4 general serv ...

vehicle with flame–projector; sixty of these were ordered for the protection of Royal Naval Air Station

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wi ...

s. The Heavy Cockatrice was based on the larger AEC Matador

The AEC Matador was a heavy 4×4 truck and medium artillery tractor built by the Associated Equipment Company for British and Commonwealth forces during World War II. AEC had already built a 4×2 lorry, also known as the Matador (all AEC lorries ...

6×6 chassis already in RAF service as a fuel bowser; six of these were constructed for RAF airfield defence. Other than having a larger fuel tank, the Heavy Cockatrice was the same vehicle. The Army showed little interest in Cockatrice, and it never went into mass production.

The flamethrower from Cockatrice was also deployed on a number of small ships. German pilots were in the habit of attacking coastal vessels, flying in very low hoping to avoid detection and dropping their bombs before flying over the ship at mast height. Norway thought that a vertical flamethrower might discourage such attacks. An experiment with a Cockatrice-like flamethrower on board ''La Patrie'', the flame's length was increased by the up-draft of the heat generated so that the pillar of fire reached vertically. A pilot was found to make dummy attacks, flying closer and closer with each pass he eventually had his wingtip virtually in the flame. Norway was disheartened to find that the pilot was not more deterred by the flames, but the pilot had been briefed to know what to expect. In a later trial with a pilot who had not been told about the flame weapon, Norway was dismayed to see that he flew with half a wing cutting into the flame. This pilot had worked for a stunt firm, so was used to driving cars "through plates of glass and walls of fire". Despite these discouraging results, the flamethrower was installed on a number of coastal vessels. Although seemingly unable to do any real damage, intelligence sources indicated that the height of attacks went up well above .

The Admiralty also ordered a version of Cockatrice that could be taken from a lorry and mounted on a landing craft to make a landing craft assault

Landing Craft Assault (LCA) was a landing craft used extensively in World War II. Its primary purpose was to ferry troops from transport ships to attack enemy-held shores. The craft derived from a prototype designed by John I. Thornycroft Ltd. ...

(flame thrower) or LCA(FT). The LCA(FT) does not appear to have been used in action. A successor to Cockatrice called Basilisk was designed with improved cross-country performance, for use with armoured car regiments, but it was not adopted and only a prototype was produced.

Ronson

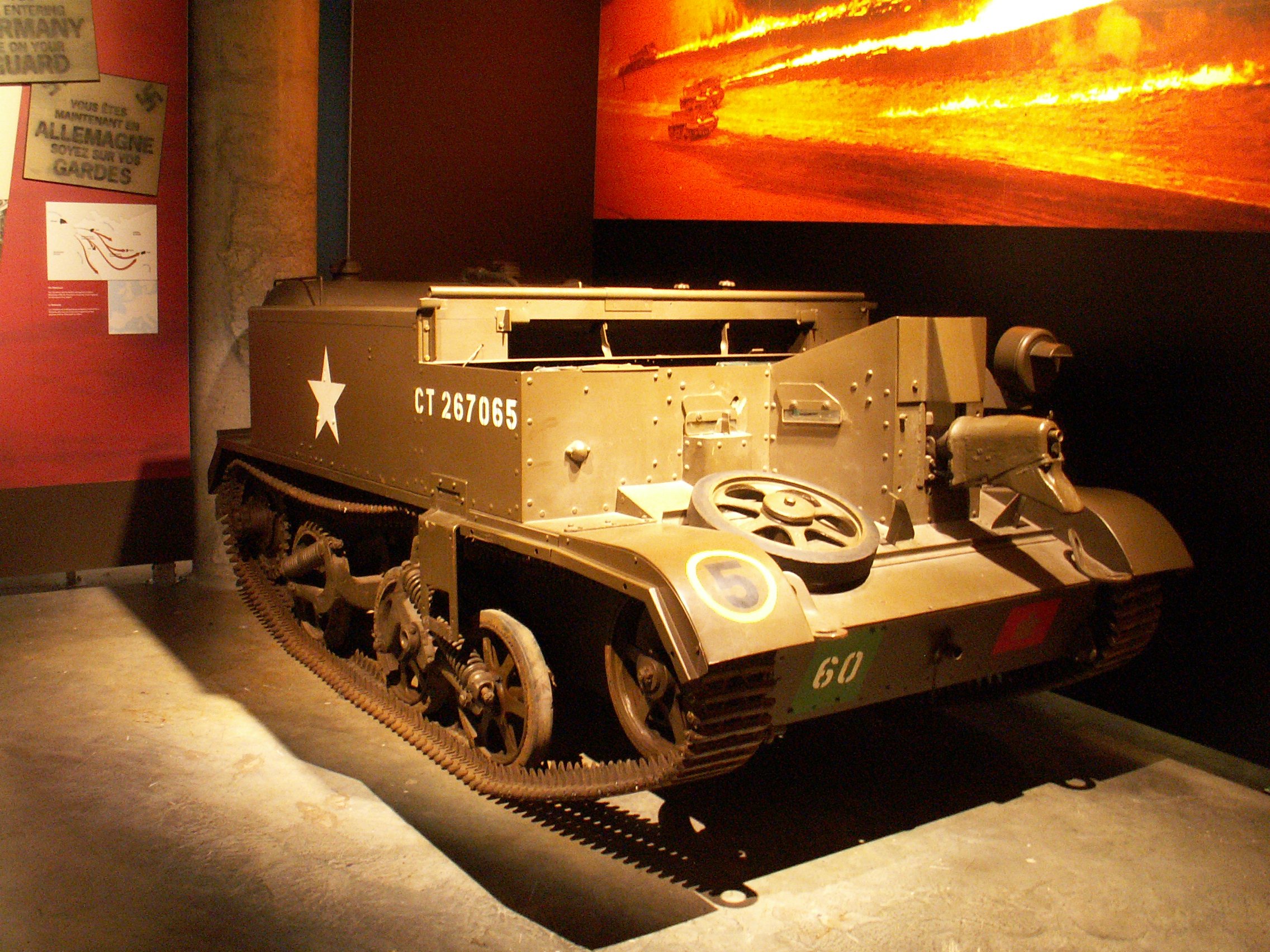

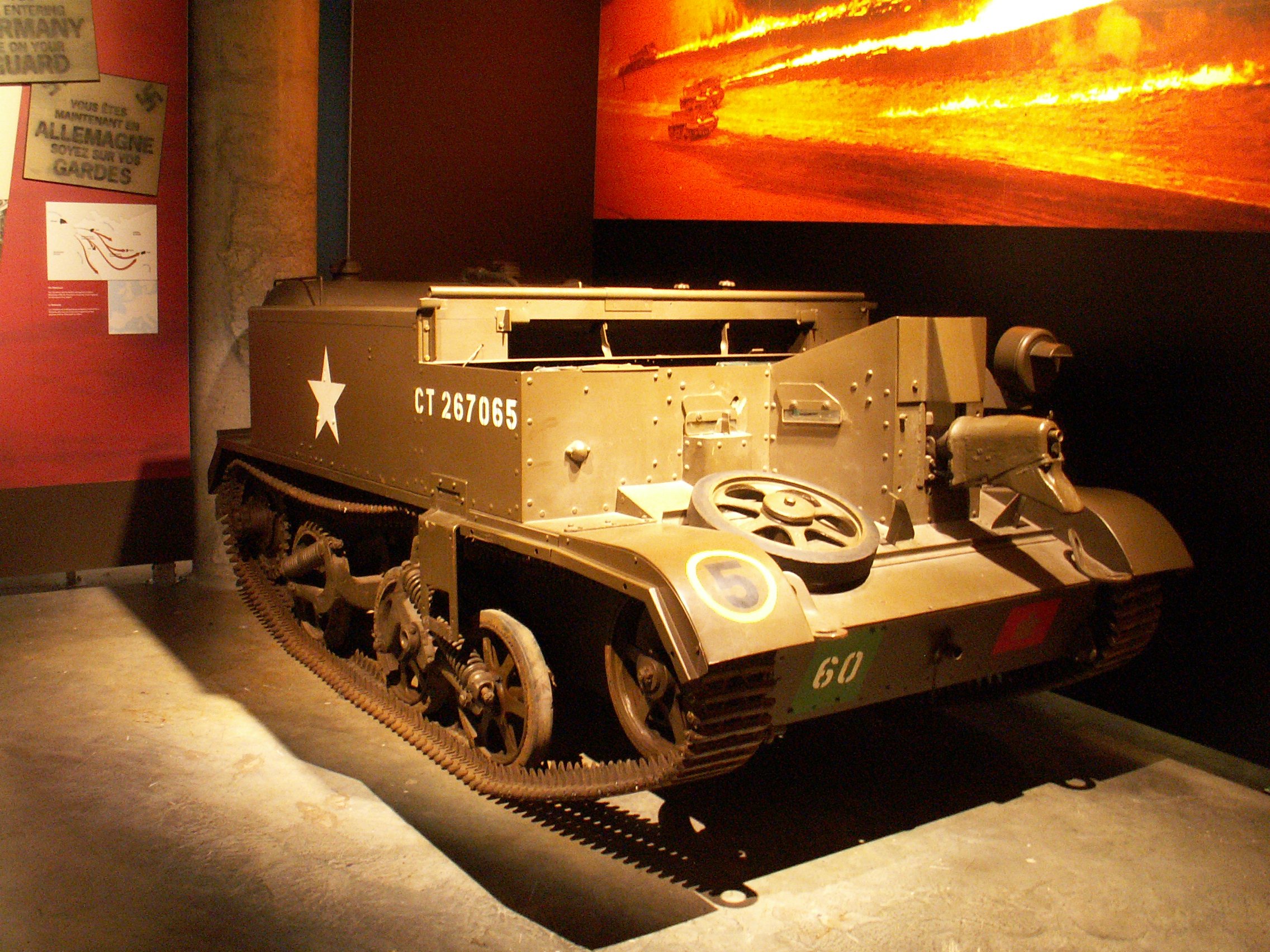

The first British vehicle mounted flamethrower for regular army use was developed in 1940 by the then newly established PWD. This flamethrower was known as the ''Ronson'' after the cigarette lighter manufacturer of the same name known for its stylish and dependable cigarette lighter products. Fraser developed the Ronson from his original Cockatrice prototypes. The Ronson was mounted on a

The first British vehicle mounted flamethrower for regular army use was developed in 1940 by the then newly established PWD. This flamethrower was known as the ''Ronson'' after the cigarette lighter manufacturer of the same name known for its stylish and dependable cigarette lighter products. Fraser developed the Ronson from his original Cockatrice prototypes. The Ronson was mounted on a Universal Carrier

The Universal Carrier, also known as the Bren Gun Carrier and sometimes simply the Bren Carrier from the light machine gun armament, is a common name describing a family of light armoured tracked vehicles built by Vickers-Armstrongs and othe ...

which was an open topped, lightly armoured tracked vehicle. The Ronson had fuel and compressed gas mounted tanks over the rear of the vehicle. The British Army turned the design down for various reasons but specifically requiring greater range.

Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is frequently shortened to "Andy" or "Drew". The word is derived ...

, commander of Canadian forces in Britain, was an imaginative officer with a keen eye for potential new weapons. He played a significant part in the development of flamethrowers and ordered 1,300 Ronsons on his own initiative. The Canadians eventually developed the Wasp Mk IIC (see below) which became the preferred model. The Ronson was also attached to the Churchill tank. Fraser was told that a tank was preferable to the Universal Carrier as a mount for a flamethrower, because it was very much less vulnerable. A Churchill MkII tank was modified as a prototype by 24 March 1942, it had a pair of Ronson projectors one on either side of the front of the hull, they could not be aimed except by moving the entire vehicle. Fuel was held in a pair of containers projecting from the rear of the vehicle. Major J. M. Oke contributed to the design, including a suggestion that the fuel be held in the reserve fuel tank – a lightly armoured standard fitting available for the Churchill tank. The design was reduced to a single flame projector and became known as the Churchill Oke. Three Churchill Okes were included as part of the tank support for the Dieppe Raid

Operation Jubilee or the Dieppe Raid (19 August 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied amphibious attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in northern France, during the Second World War. Over 6,050 infantry, predominantly Canadian, s ...

but did not get to use the flamethrowers in combat.

From the Canadians, the Ronson came to the attention of the United States who later developed it use as a replacement for the main gun on obsolete M3A1 tank, a weapon that was called ''Satan''. Later, other models of the M3 Stuart were fitted with similar flamethrowers alongside the main armament. Satan and others would see action in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

and during Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

.

Wasp

By 1942 the PWD had developed the Ronson flamethrowers so that a range of was achieved. In September 1942, this improved appliance was put into production as the Wasp Mk I. An order for 1,000 was placed and all had been delivered by November 1943. The Wasp Mk I had two fuel tanks located inside the carrier's hull and used a large projector gun that was mounted over the top of the carrier. The Mk I was immediately outdated by the development of the Wasp Mk II which had a much handier flame projector mounted at the front on the machine-gun mounting. Although there was no improvement in range, this version performed much better being easier to aim and much safer to use.

The Wasp Mk II went into action during the

By 1942 the PWD had developed the Ronson flamethrowers so that a range of was achieved. In September 1942, this improved appliance was put into production as the Wasp Mk I. An order for 1,000 was placed and all had been delivered by November 1943. The Wasp Mk I had two fuel tanks located inside the carrier's hull and used a large projector gun that was mounted over the top of the carrier. The Mk I was immediately outdated by the development of the Wasp Mk II which had a much handier flame projector mounted at the front on the machine-gun mounting. Although there was no improvement in range, this version performed much better being easier to aim and much safer to use.

The Wasp Mk II went into action during the Invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...