Peter Fraser (New Zealand politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

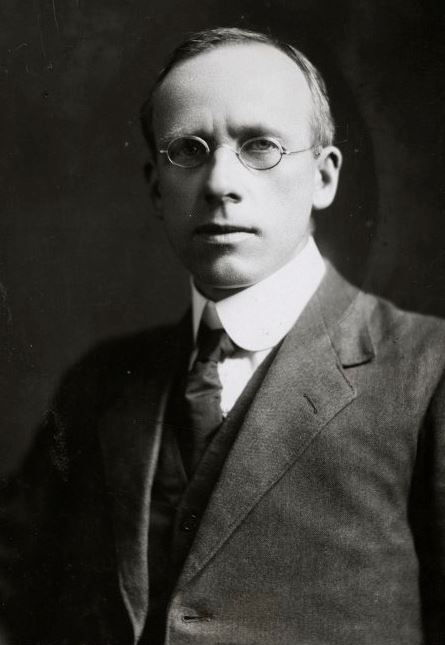

Peter Fraser (; 28 August 1884 – 12 December 1950) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 24th

In a 1918 by-election, Fraser gained election to Parliament, winning the electorate of . He soon distinguished himself through his work to counter the influenza epidemic of 1918–19, of which Fraser was himself a survivor.

During his early years in parliament, Fraser developed a clearer sense of his political beliefs. Although initially enthusiastic about the Russian

In a 1918 by-election, Fraser gained election to Parliament, winning the electorate of . He soon distinguished himself through his work to counter the influenza epidemic of 1918–19, of which Fraser was himself a survivor.

During his early years in parliament, Fraser developed a clearer sense of his political beliefs. Although initially enthusiastic about the Russian

As Minister of Health, Fraser also became the driving force behind the 1938 Social Security Act. The Act proposed a comprehensive health care system, free at the point of use; it faced strong opposition, particularly from the New Zealand branch of the

As Minister of Health, Fraser also became the driving force behind the 1938 Social Security Act. The Act proposed a comprehensive health care system, free at the point of use; it faced strong opposition, particularly from the New Zealand branch of the

Fraser was one of the immediate few in New Zealand who instantly grasped that war meant not merely the involvement of the military, but that of the whole country. These implications were not always recognised either by his own party or by the opposition. Fraser further developed somewhat of an authoritarian streak as a result; this reflected his insistence on the overwhelming importance of the war effort above all else.

During the war, Fraser attempted to build support for an understanding between Labour and its main rival, the National Party. However, opposition within both parties prevented reaching an agreement, and Labour continued to govern alone. Fraser did, however, work closely with

Fraser was one of the immediate few in New Zealand who instantly grasped that war meant not merely the involvement of the military, but that of the whole country. These implications were not always recognised either by his own party or by the opposition. Fraser further developed somewhat of an authoritarian streak as a result; this reflected his insistence on the overwhelming importance of the war effort above all else.

During the war, Fraser attempted to build support for an understanding between Labour and its main rival, the National Party. However, opposition within both parties prevented reaching an agreement, and Labour continued to govern alone. Fraser did, however, work closely with  Fraser had a very rocky relationship with U.S. Secretary of State

Fraser had a very rocky relationship with U.S. Secretary of State

Fraser's Government had proposed to adopt the

Fraser's Government had proposed to adopt the

Although he relinquished the role of Minister of Education early in his term as Prime Minister, he and

Although he relinquished the role of Minister of Education early in his term as Prime Minister, he and

Prime Minister's Office biography

by Michael Bassett * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fraser, Peter Prime Ministers of New Zealand New Zealand Labour Party MPs New Zealand foreign ministers New Zealand Labour Party leaders World War II political leaders Scottish politicians Scottish emigrants to New Zealand People from Ross and Cromarty Politicians from Wellington City 1884 births 1950 deaths Leaders of the Opposition (New Zealand) Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives New Zealand education ministers New Zealand MPs for Wellington electorates New Zealand anti–World War I activists New Zealand politicians convicted of crimes New Zealand members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom New Zealand Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Social Democratic Party (New Zealand) politicians Burials at Karori Cemetery Wellington City Councillors Wellington Harbour Board members

prime minister of New Zealand

The prime minister of New Zealand ( mi, Te pirimia o Aotearoa) is the head of government of New Zealand. The prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, leader of the New Zealand Labour Party, took office on 26 October 2017.

The prime minister (inf ...

from 27 March 1940 until 13 December 1949. Considered a major figure in the history of the New Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party ( mi, Rōpū Reipa o Aotearoa), or simply Labour (), is a centre-left political party in New Zealand. The party's platform programme describes its founding principle as democratic socialism, while observers desc ...

, he was in office longer than any other Labour prime minister, and is to date New Zealand's fourth- longest-serving head of government.

Born and raised in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

, Fraser left education early in order to support his family. While working in London in 1908, Fraser joined the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

, but unemployment led him to emigrate to New Zealand in 1910. On arrival in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

, he gained employment as a wharfie

A stevedore (), also called a longshoreman, a docker or a dockworker, is a waterfront manual laborer who is involved in loading and unloading ships, trucks, trains or airplanes.

After the shipping container revolution of the 1960s, the number o ...

and became involved in union politics upon joining the New Zealand Socialist Party

The New Zealand Socialist Party was founded in 1901, promoting the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The group, despite being relatively moderate when compared with many other socialists, met with little tangible success, but it neverthe ...

. In 1916, Fraser was involved in the foundation of the unified Labour Party. He spent one year in jail for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

after speaking out against conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

during the First World War. In 1918, Fraser won a Wellington by-election and entered the House of Representatives.

Fraser became a cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

minister in , serving under Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 23rd prime minister of New Zealand, heading the First Labour Government from 1935 until his death in 1940.

Savage was born in the Colon ...

. He held several portfolios and had a particular interest in education, which he considered vital for social reform. As Minister of Health, he introduced the Social Security Act 1938

The Social Security Act 1938 is a New Zealand Act of Parliament concerning unemployment insurance which established New Zealand as a welfare state. This act is important in the history of social welfare, as it established the first ever social s ...

, which established a universal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized ar ...

service. Fraser became the Leader of the Labour Party and Prime Minister in 1940, following Savage's death in office.

Fraser is best known for leading the country during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

when he mobilised New Zealand supplies and volunteers to support Britain while boosting the economy and maintaining home front morale. He formed a war cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

which included several erstwhile political opponents. Labour suffered significant losses in the election, though the party retained its majority.

Following the war, Fraser was active in the affairs of the 'new' Commonwealth and is credited with increasing New Zealand's international stature. Fraser led his party to its fourth successive election victory in , albeit with a further reduced majority. The after-effects of the war, including ongoing shortages, were affecting his government's popularity. Labour lost the and Fraser's government was succeeded by the first National Party government.

Early life

A native ofScotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Peter Fraser was born in Hill of Fearn

Hill of Fearn ( gd, Baile an Droma) is a small village near Tain in Easter Ross, in the Scottish council area of Highland.

Geography

The village is on the B9165 road, between the A9 trunk road and the smaller hamlet of Fearn to the southeast ...

, a small village near the town of Tain

Tain ( Gaelic: ''Baile Dhubhthaich'') is a royal burgh and parish in the County of Ross, in the Highlands of Scotland.

Etymology

The name derives from the nearby River Tain, the name of which comes from an Indo-European root meaning 'flow'. Th ...

in the Highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated mountainous plateau or high hills. Generally speaking, upland (or uplands) refers to ranges of hills, typically from up to while highland (or highlands) is ...

area of Easter Ross

Easter Ross ( gd, Ros an Ear) is a loosely defined area in the east of Ross, Highland, Scotland.

The name is used in the constituency name Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross, which is the name of both a British House of Commons constitue ...

. He received a basic education, but had to leave school due to his family's poor financial state. Though apprenticed to a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters t ...

, he eventually abandoned this trade due to extremely poor eyesight – later in life, faced with difficulty reading official documents, he would insist on spoken reports rather than written ones. Before the deterioration of his vision, however, he read extensively – with socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

activists such as Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

and Robert Blatchford among his favourites.

Becoming politically active in his early teens, he was 16 years old upon attaining the post of secretary of the local Liberal Association, and, eight years later, in 1908, joined the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

.

Move to New Zealand

In another two years, at the age of 26, after unsuccessfully seeking employment inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, Fraser decided to move to New Zealand, having apparently chosen the country in the belief that it possessed a strong progressive spirit.

He gained employment as a stevedore

A stevedore (), also called a longshoreman, a docker or a dockworker, is a waterfront manual laborer who is involved in loading and unloading ships, trucks, trains or airplanes.

After the shipping container revolution of the 1960s, the number ...

(or "wharfie") on arrival in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

, and became involved in union politics upon joining the New Zealand Socialist Party

The New Zealand Socialist Party was founded in 1901, promoting the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The group, despite being relatively moderate when compared with many other socialists, met with little tangible success, but it neverthe ...

. Fraser worked as campaign manager for Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 23rd prime minister of New Zealand, heading the First Labour Government from 1935 until his death in 1940.

Savage was born in the Colon ...

as the Socialist candidate for Auckland Central electorate. He was also involved in the New Zealand Federation of Labour, which he represented at Waihi

Waihi is a town in Hauraki District in the North Island of New Zealand, especially notable for its history as a gold mine town.

The town is at the foot of the Coromandel Peninsula, close to the western end of the Bay of Plenty. The nearby re ...

during the Waihi miners' strike of 1912. He moved to Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

, the country's capital, shortly afterwards. Savage went on to be Fraser's predecessor in office as the nation's first Labour Prime Minister.

In 1913, he participated in the founding of the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

and, during the year, within the scope of his union activities, found himself under arrest for breaches of the peace. While the arrest led to no serious repercussions, it did prompt a change of strategy – he moved away from direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

and began to promote a parliamentary route to power.

Upon Britain's entry into the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he strongly opposed New Zealand participation since, sharing the belief of many leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

thinkers, Fraser considered the conflict an "imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

war", fought for reasons of national interest rather than of principle.

Foundation of the Labour Party

In 1916, Fraser became involved in the foundation of theNew Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party ( mi, Rōpū Reipa o Aotearoa), or simply Labour (), is a centre-left political party in New Zealand. The party's platform programme describes its founding principle as democratic socialism, while observers desc ...

, which absorbed much of the moribund Social Democratic Party's membership. The members selected Harry Holland

Henry Edmund Holland (10 June 1868 – 8 October 1933) was an Australian-born newspaper owner, politician and unionist who relocated to New Zealand. He was the second leader of the New Zealand Labour Party.

Early life

Holland was born at ...

as the Labour Party's leader. Michael Joseph Savage, Fraser's old ally from the New Zealand Socialist Party, also participated.

Later in 1916, the government had Fraser and several other members of the new Labour Party arrested on charges of sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

. This resulted from their outspoken opposition to the war, and particularly their call to abolish conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

. Fraser received a sentence of one year in jail. He always rejected the verdict, claiming he would only have committed subversion had he taken active steps to undermine conscription, rather than merely voicing his disapproval.

After his release from prison, Fraser worked as a journalist for the official Labour Party newspaper. He also resumed his activities within the Labour Party, initially in the role of campaign manager for Harry Holland.

Local body politics

In1919

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Pressburg (now Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY ''Iolaire'' sinks off the ...

Fraser stood on the Labour Party's ticket for the Wellington City Council

Wellington City Council is a territorial authority in New Zealand, governing the country's capital city Wellington, and ''de facto'' second-largest city (if the commonly considered parts of Wellington, the Upper Hutt, Porirua, Lower Hutt and ...

. He and three others were first Labour candidates to win office on the council since before the war. Fraser led a movement on the council to establish a municipal milk distribution department in Wellington, which was to remain in operation until the 1990s. He was re-elected in 1921, though Labour lost ground only winning two seats. In 1923

Events

January–February

* January 9 – Lithuania begins the Klaipėda Revolt to annex the Klaipėda Region (Memel Territory).

* January 11 – Despite strong British protests, troops from France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr area, t ...

Fraser stood for Mayor of Wellington

The Mayor of Wellington is the head of the municipal government of the City of Wellington. The mayor presides over the Wellington City Council. The mayor is directly elected using the Single Transferable Vote method of proportional representat ...

. He adopted an "all or nothing" strategy by standing only for the mayoralty, refusing nomination to stand for the council also. Fraser polled higher than any Labour mayoral candidate in New Zealand history but lost by only 273 votes to Robert Wright in the closest result Wellington had ever seen.

Fraser made a comeback on the council when he was persuaded to stand in a 1933 by-election. Wright was his main opponent and was victorious in a heavy polling contest which was dubbed by the media as a "grudge match" repeat of 1923. Fraser was re-elected to the Council in 1935

Events

January

* January 7 – Italian premier Benito Mussolini and French Foreign Minister Pierre Laval conclude an agreement, in which each power agrees not to oppose the other's colonial claims.

* January 12 – Amelia Earhart ...

, topping the poll with more votes than any other candidate. The next year he decided to resign from the council in order to focus on his ministerial duties. A by-election was avoided when Andrew Parlane, also the highest polling unsuccessful candidate from 1935, was the only nominated candidate.

Early parliamentary career

In a 1918 by-election, Fraser gained election to Parliament, winning the electorate of . He soon distinguished himself through his work to counter the influenza epidemic of 1918–19, of which Fraser was himself a survivor.

During his early years in parliament, Fraser developed a clearer sense of his political beliefs. Although initially enthusiastic about the Russian

In a 1918 by-election, Fraser gained election to Parliament, winning the electorate of . He soon distinguished himself through his work to counter the influenza epidemic of 1918–19, of which Fraser was himself a survivor.

During his early years in parliament, Fraser developed a clearer sense of his political beliefs. Although initially enthusiastic about the Russian October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

of 1917 and its Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

leaders, he rejected them soon afterwards, and eventually became one of the strongest advocates of excluding communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

s from the Labour Party. His commitment to parliamentary politics rather than to direct action became firmer, and he had a moderating influence on many Labour Party policies.

Fraser's views clashed considerably with those of Harry Holland, still serving as leader, but the party gradually shifted its policies away from the more extreme left of the spectrum. Fraser soon became convinced that political action via parliamentary process was the only realistic course of action to achieve Labour movement ambitions. As a result, he accepted the inevitable compromises (which Holland did not) that the attainment of parliamentary success required.

In 1933, however, Holland died, leaving the leadership vacant. Fraser considered contesting it, but eventually endorsed Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 23rd prime minister of New Zealand, heading the First Labour Government from 1935 until his death in 1940.

Savage was born in the Colon ...

, Holland's more moderate deputy. Fraser became the new deputy leader. While Savage represented perhaps less moderate views than Fraser, he lacked the extreme ideology of Holland. With Labour now possessing a "softer" image and the existing conservative coalition struggling with the effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, Savage's party succeeded in winning the and forming a government.

Fraser served as vice-president of the Labour Party in 1919–1920, and as party president in 1920–1921.

Cabinet minister

In the new administration, Fraser became the Minister of External Affairs, the Minister of Island Territories, Minister of Health, Minister of Education andMinister of Marine

One of France's Secretaries of State under the Ancien Régime was entrusted with control of the French Navy ( Secretary of State of the Navy (France).) In 1791, this title was changed to Minister of the Navy. Before January 1893, this position als ...

. He showed himself extremely active as a minister, often working seventeen hours a day, seven days a week. During his first years in cabinet, his wife, Janet

Janet may refer to:

Names

* Janet (given name)

* Janet (French singer) (1939–2011)

Surname

* Charles Janet (1849–1932), French engineer, inventor and biologist, known for the Left Step periodic table

* Jules Janet (1861–1945), French psych ...

, had an office next to his and worked as his research assistant and adviser in order that she could spend time with him. She would also prepare meals for him during his long days at parliament.

He had a particular interest in education, which he considered vital for social reform. His appointment of C.E. Beeby to the Education Department provided him with a valuable ally for these reforms. Fraser held a passionate belief that education had a huge part to play in the social reform he desired.

Fraser's narrowly elitist and Anglophile cultural perspectives are illustrated by his crucial role in planning New Zealand's 1940 Centennial celebrations. He used his cultural protege James Shelly, an Englishman who insisted that England was to be the source of New Zealand's cultural life – and by 'cultural' Shelley and Fraser meant so-called high culture sourced from England. As head of the 1940 Centennial Musical Celebrations Shelley followed Fraser in insisting the music would be 'high' culture only. He reassured Fraser that "established Musical Societies, who, throughout New Zealand’s history, have done such magnificent and effective work in developing and keeping alive that appreciation of good music which is so essential to the cultural development of the people of any country." To implement this the Government would import from England "a Musical Adviser and a sufficient number of outstanding Soloists." The result:"a sumtuous feast of good music." Neither Fraser nor Shelley contemplated involving New Zealand born performers and artists.

As Minister of Health, Fraser also became the driving force behind the 1938 Social Security Act. The Act proposed a comprehensive health care system, free at the point of use; it faced strong opposition, particularly from the New Zealand branch of the

As Minister of Health, Fraser also became the driving force behind the 1938 Social Security Act. The Act proposed a comprehensive health care system, free at the point of use; it faced strong opposition, particularly from the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headqua ...

. Eventually, Fraser negotiated effectively enough to force the Association to yield. Fortunately for him, Janet Fraser had long volunteered in the health and welfare fields and was an invaluable adviser and collaborator.

When the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

broke out in 1939, Fraser had already taken over most of the functions of national leadership

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets v ...

. Michael Joseph Savage had been ill for some time and was near death, although the authorities concealed this from the public. Fraser had to assume most of the Prime Minister's duties in addition to his own ministerial ones. Internal disputes within the Labour Party made Fraser's position more difficult. John A. Lee

John Alfred Alexander Lee (31 October 1891 – 13 June 1982) was a New Zealand politician and writer. He is one of the more prominent avowed socialists in New Zealand's political history.

Lee was elected as a member of parliament in 1922 ...

, a notable socialist within the Party, vehemently disapproved of the party's perceived drift towards the political centre, and strongly criticised Savage and Fraser. Lee's attacks, however, became strong enough that even many of his supporters denounced them. Fraser and his allies successfully moved to expel Lee from the Party on 25 March 1940.

Prime Minister

Savage died two days later, on 27 March, and Fraser successfully contested the leadership againstGervan McMillan

David Gervan McMillan (26 February 1904 – 20 February 1951) was a New Zealand politician of the Labour Party, and a medical practitioner.

Biography

McMillan was born in 1904 in New Plymouth, the eldest child of Annie Gertrude Pearce and ...

and Clyde Carr

Clyde Leonard Carr (14 January 1886 – 18 September 1962) was a New Zealand politician of the Labour Party, and was a minister of the Congregational Church.

Biography Early life and career

Carr was born in Ponsonby, Auckland in 1886. His fa ...

. He had, however, to give the party's caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to a meeting ...

the right to elect people to Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

without the Prime Minister's approval – a practice which has continued as a feature of the Labour Party .

Despite the concession, Fraser remained in command, occasionally alienating colleagues due to a governing style described by some as "authoritarian". Some of his determination to exercise control may have come about due to the war, on which Fraser focused almost exclusively. Nevertheless, certain measures he implemented, such as censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

, wage control

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Bec ...

s, and conscription, proved unpopular with the party. In particular, conscription provoked strong opposition, especially since Fraser himself had opposed it during the First World War. Fraser replied that fighting in the Second World War, unlike in the First World War, had indeed a worthy cause, making conscription a necessary evil. Despite opposition from within the Labour Party, enough of the general public supported conscription to allow its acceptance.

Second World War

Fraser was one of the immediate few in New Zealand who instantly grasped that war meant not merely the involvement of the military, but that of the whole country. These implications were not always recognised either by his own party or by the opposition. Fraser further developed somewhat of an authoritarian streak as a result; this reflected his insistence on the overwhelming importance of the war effort above all else.

During the war, Fraser attempted to build support for an understanding between Labour and its main rival, the National Party. However, opposition within both parties prevented reaching an agreement, and Labour continued to govern alone. Fraser did, however, work closely with

Fraser was one of the immediate few in New Zealand who instantly grasped that war meant not merely the involvement of the military, but that of the whole country. These implications were not always recognised either by his own party or by the opposition. Fraser further developed somewhat of an authoritarian streak as a result; this reflected his insistence on the overwhelming importance of the war effort above all else.

During the war, Fraser attempted to build support for an understanding between Labour and its main rival, the National Party. However, opposition within both parties prevented reaching an agreement, and Labour continued to govern alone. Fraser did, however, work closely with Gordon Coates

Joseph Gordon Coates (3 February 1878 – 27 May 1943) served as the 21st prime minister of New Zealand from 1925 to 1928. He was the third successive Reform prime minister since 1912.

Born in rural Northland, Coates grew up on a cattle run a ...

, a former Prime Minister and now a National-Party rebel – Fraser praised Coates for his willingness to set aside his party loyalty, and appears to have believed that National leader Sidney Holland

Sir Sidney George Holland (18 October 1893 – 5 August 1961) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 25th prime minister of New Zealand from 13 December 1949 to 20 September 1957. He was instrumental in the creation and consolidation o ...

placed the interests of his party before national unity.

In terms of the war effort itself, Fraser had a particular concern with ensuring that New Zealand retained control over its own forces. He believed that the more populous countries, particularly Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, viewed New Zealand's military as a mere extension of their own, rather than as the armed forces of a sovereign nation. After particularly serious New Zealand losses in the Greek campaign in 1941, Fraser determined to retain a say as to where to deploy New Zealand troops. Fraser insisted to British leaders that Bernard Freyberg

Lieutenant-General Bernard Cyril Freyberg, 1st Baron Freyberg, (21 March 1889 – 4 July 1963) was a British-born New Zealand soldier and Victoria Cross recipient, who served as the 7th Governor-General of New Zealand from 1946 to 1952.

Frey ...

, commander of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was the title of the military forces sent from New Zealand to fight alongside other British Empire and Dominion troops during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). Ultimately, the NZE ...

, should report to the New Zealand government just as extensively as to the British authorities.

When Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

entered the war in December 1941, Fraser had to choose between recalling New Zealand's forces to the Pacific (as Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

had done) or keeping them in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

(as British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

requested). Opinion was divided on the question and New Zealand's manpower resources were already stretched to capacity. Fraser received assurances from the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt that American forces would be made available for New Zealand's defense, the local populace possessed an understandable view that division that their proper place was defending their homes. Fraser weighed up public opinions against the strategic arguments involved and eventually opted to leave New Zealand's Expeditionary Force where it was.

In a remarkable display of political acumen and skill, he then persuaded a divided government and Parliament to give their full supporto leave the army in Africa O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), plu ...It was leadership of the highest order.

Fraser had a very rocky relationship with U.S. Secretary of State

Fraser had a very rocky relationship with U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

, particularly over the Canberra Pact in January 1944. Hull gave Fraser a sharp and rather demeaning dressing-down when Fraser visited Washington D.C. in mid-1944, which resulted in New Zealand's military becoming sidelined to some extent in the conduct of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

.

Furlough Mutiny

By early 1943 Fraser faced a major military and strategic problem that also had significant political implications in this New Zealand election year. The New Zealand Division, part of the Eighth Army in North Africa, were now battle-weary. The bulk of the Division had been overseas for almost three years. Nearly 43% of the troops had suffered casualties. "The men were homesick, exhausted and war-weary." In 1943 Fraser arranged for 6,000 men to return home from the Mediterranean theatre for a three-month furlough (period of military leave), anticipating that the grateful men and their families would be more disposed to vote Labour in the general election. Upon arrival, however, many of the veterans were furious at the numbers in reserved occupations, some of whom were making menial goods of no use to the war effort. Moreover, unions had ensured that bonuses and high pay were awarded to munitions workers, far in excess of the money paid to the men in combat. "No man twice before every man first" became one of the returning soldiers' mantras, and several thousand of them secured an exemption from further service due to age or being married. A number of the remainder werecourt-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed, sentenced to 90 days' imprisonment and forced to return (though some had deserted and were not able to be found. Further, they were denied a military pension and refused government jobs. Due to censorship, the public heard little of the protests and the affair, known as the "Furlough Mutiny", was omitted from post-war history books for many years.

Trans-Tasman relationship

Fraser's government also established a far closer working understanding with the Labor government in Australia. He signed the Australian–New Zealand Agreement of 1944, in which Fraser, under pressure by Australia's foreign minister, H. V. Evatt, overplayed his hand seeking to ensure that both Australian and New Zealand interests in the Pacific would not be overlooked in the war or its aftermath. New Zealand and Australia were both anxious to have their input in the planning of the Pacific War, and later in the decisions of the "Great Powers" in the shaping of the post-war world.Post-war

After the war ended, Fraser devoted much attention to the formation of theUnited Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

at the San Francisco conference

A conference is a meeting of two or more experts to discuss and exchange opinions or new information about a particular topic.

Conferences can be used as a form of group decision-making, although discussion, not always decisions, are the main p ...

(UNCIO) in 1945; this "was the apogee of Fraser's career". Noteworthy for his strong opposition to vesting powers of veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

in permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

, he often spoke unofficially for smaller states. He was elected chairman of one of the main committees which was considering dependent territories, and next year in London was chairman of one of the social-economic committees at the first assembly in London. He earned the respect of many world statesmen through his commitment to principle, his energy, and most of all his skill as a chairman. It was to Fraser's stature that New Zealand would later owe much of its favourable international reputation.

Fraser had a particularly close working relationship with Alister McIntosh

Sir Alister Donald Miles McIntosh (29 November 1906 – 30 November 1978) was a New Zealand diplomat. McIntosh was New Zealand's first secretary of foreign affairs serving as the principal foreign policy adviser to Prime Ministers Peter Fraser, ...

, the head of the Prime Minister's department during most of Fraser's premiership and then of the Department of External Affairs, created in 1946. McIntosh privately described his frustration with Fraser's workaholism, and with Fraser's insensitivity towards officials' needs for private lives; but the two men had a genuinely affectionate relationship.

Fraser also took up the role of Minister of Native Affairs

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governmen ...

(which he renamed Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

Affairs) in 1947. Fraser had had an interest in Māori concerns for some time, and he implemented a number of measures designed to reduce inequality. The Maori Social and Economic Advancement Act, which he introduced in 1945, allowed Māori involvement and control over welfare programmes and other assistance.

New Commonwealth

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that sets the basis for the relationship between the Commonwealth realms and the Crown.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of the ...

in its Speech from the Throne

A speech from the throne, or throne speech, is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign, or a representative thereof, reads a prepared speech to members of the nation's legislature when a session is opened, outlining t ...

in 1944 (two years after Australia adopted the Act), in order to gain greater constitutional independence. During the Address-In-Reply debate, the opposition passionately opposed the proposed adoption, claiming the Government was being disloyal to the United Kingdom. National MP for Tauranga

Tauranga () is a coastal city in the Bay of Plenty region and the fifth most populous city of New Zealand, with an urban population of , or roughly 3% of the national population. It was settled by Māori late in the 13th century, colonised by ...

, Frederick Doidge, argued "With us, loyalty is an instinct as deep as religion".

The proposal was buried. Ironically, the National opposition prompted the adoption of the Statute in 1947 when its leader and future Prime Minister Sidney Holland

Sir Sidney George Holland (18 October 1893 – 5 August 1961) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 25th prime minister of New Zealand from 13 December 1949 to 20 September 1957. He was instrumental in the creation and consolidation o ...

introduced a private members' bill to abolish the Legislative Council, the country's upper house of parliament. Because New Zealand required the consent of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

to amend the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 (15 & 16 Vict. c. 72) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that granted self-government to the Colony of New Zealand. It was the second such Act, the previous 1846 Act not having been fully ...

, Fraser decided to adopt the Statute with the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1947

The Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1947 (Public Act no. 38 of 1947) was a constitutional Act of the New Zealand Parliament that formally accepted the full external autonomy offered by the British Parliament. By passing the Act on 25 November ...

.

The adoption of the Statute of Westminster was soon followed by the debate on the future of the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

in its transformation into the Commonwealth of Nations. In April 1949 Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, formerly the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

, declared itself a republic and ceased to be a member of the Commonwealth. In response to this, the New Zealand Parliament passing the Republic of Ireland Act the following year, which treated Ireland as if it were still a member of the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, newly independent India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

would have to leave the Commonwealth on becoming a republic also, although it was the Indian Prime Minister's view that India should remain a member of the Commonwealth as a republic. Fraser believed that the Commonwealth could as a group address the evils of colonialism and maintain the solidarity of common defence.

To Fraser, the acceptance of India as a republican member would threaten the political unity of the Commonwealth. Fraser knew his domestic audience and was tough on republicanism or defence weakness to deflect criticism from the loyalist and imperialist-minded opposition National Party. Labour had been in office for fourteen years and faced an uphill battle to retain power against National at the general election, which would come just months after the high-profile April 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference

Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences were biennial meetings of Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominion members of the British Commonwealth of Nations. Seventeen Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences were held betwee ...

. In March 1949 Fraser wrote to the Canadian Prime Minister, Louis St Laurent

Louis Stephen St. Laurent (''Saint-Laurent'' or ''St-Laurent'' in French, baptized Louis-Étienne St-Laurent; February 1, 1882 – July 25, 1973) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 12th prime minister of Canada from 19 ...

, stating his frustration and unease over India's position. Saint Laurent had indicated that he would not be able to attend the meeting where the issue of India's republican status would dominate. Fraser argued:

Fraser left little doubt New Zealand was opposed to India's membership as a republic when he stated to his colleagues at Downing Street:

The conference quashed a proposal of a two-tier structure that would have had the traditional Commonwealth realms

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonweal ...

, perhaps with defence pacts, on one tier, and the new members which opted for a republic, on the second tier. The final compromise is perhaps best seen from the title finally accepted for the King, as Head of the Commonwealth

The head of the Commonwealth is the ceremonial leader who symbolises "the free association of independent member nations" of the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation that currently comprises 56 sovereign states. There is ...

.

Fraser argued that the compromise allowed the Commonwealth dynamism, that would in the future allow former colonies of Africa to join as republics and be stalwarts of this New Commonwealth. It also allowed New Zealand the freedom to maintain its individual status of loyalty to the Crown and to pursue collective defence. Indeed, Fraser cabled a senior minister, Walter Nash, after the decision was taken to accept India that "while the Declaration is not as I would have wished, it is on the whole acceptable and maximum possible, and does not at any rate leave our position unimpaired".

Decline and defeat

Although he relinquished the role of Minister of Education early in his term as Prime Minister, he and

Although he relinquished the role of Minister of Education early in his term as Prime Minister, he and Walter Nash

Sir Walter Nash (12 February 1882 – 4 June 1968) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 27th prime minister of New Zealand in the Second Labour Government from 1957 to 1960. He is noted for his long period of political service, hav ...

continued to have an active role in developing educational policy with C. E. Beeby

Clarence Edward Beeby (16 June 1902 – 10 March 1998), most commonly referred to as C.E. Beeby or simply Beeb, was a New Zealand educationalist and psychologist. He was influential in the development of the education system in New Zealand, fi ...

.

Labour's majority at the was reduced to one seat. The after-effects of the war were affecting his government's popularity. Fraser moved to the Wellington seat of Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, which he held until his death. From 1940 to 1949 Fraser lived in a house "Hill Haven" at 64–66 Harbour View Road, Northland, Wellington, which had been purchased for the use of the then-ill Savage in 1939.

Fraser's domestic policies came under criticism. His slow speed in removing war-time rationing and his support for compulsory military training during peacetime in the 1949 referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

particularly damaged him politically. Some thought this hypocritical compared to Fraser's earlier sentiments on the subject. Much earlier in his career, in 1927 he is noted to have said that compulsory military training was "out of date, inefficient and not worth the money spent on it".

With dwindling support from traditional Labour voters, and a population weary of war-time measures, Fraser's popularity declined. At this stage of his career, Fraser relied heavily on the party "machine". As a result, the gap between the party leadership and rank and file members widened to the point where Labour's political enthusiasm dwindled. In the the National Party defeated his government.

Leader of the Opposition

Following the election defeat, Fraser becameLeader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, but declining health prevented him from playing a significant role. He died at the age of 66, exactly one year after leaving government. His successor as leader of the Labour Party was Walter Nash

Sir Walter Nash (12 February 1882 – 4 June 1968) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 27th prime minister of New Zealand in the Second Labour Government from 1957 to 1960. He is noted for his long period of political service, hav ...

. His successor in the electorate, elected in the 1951 Brooklyn by-election

The Brooklyn by-election 1951 was a by-election held in the electorate in Wellington during the 29th New Zealand Parliament, on 17 February 1951.

Background

The by-election was caused by the death of incumbent MP Peter Fraser, who had been Prim ...

, was Arnold Nordmeyer

Sir Arnold Henry Nordmeyer (born Heinrich Arnold Nordmeyer, 7 February 1901 – 2 February 1989) was a New Zealand politician. He served as Minister of Finance (1957–1960) and later as Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition ...

.

Personal life

On 1 November 1919, a year after his election to parliament, Fraser married Janet Kemp née Munro, from Glasgow and also a political activist. They remained together until Janet's death in 1945, five years before Fraser's own passing. During Fraser's time as Prime Minister, Janet traveled with him and acted as a "political adviser, researcher, gatekeeper and personal support system". Her ideas influenced his political philosophy. The couple had no children, although Janet had a son from her first marriage to George Kemp.Death

Fraser died in Wellington on 12 December 1950 from aheart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

following hospitalisation with influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

. His body lay in state in the New Zealand Parliament Buildings

New Zealand Parliament Buildings ( mi, Ngā whare Paremata) house the New Zealand Parliament and are on a 45,000 square metre site at the northern end of Lambton Quay, Wellington. They consist of the Edwardian neoclassical-style Parliament H ...

for three days and a state funeral service was conducted by the Moderator of the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

. He is buried in the Karori Cemetery

Karori Cemetery is New Zealand's second largest cemetery, located in the Wellington suburb of Karori.

History

Karori Cemetery opened in 1891 to address overcrowding at Bolton Street Cemetery.

In 1909, it received New Zealand's first cremat ...

.

Honours

In 1935, Fraser was awarded theKing George V Silver Jubilee Medal

The King George V Silver Jubilee Medal is a commemorative medal, instituted to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the accession of King George V.

Issue

This medal was awarded as a personal souvenir by King George V to commemorate his Silver J ...

, and in 1937, he was awarded the King George VI Coronation Medal

The King George VI Coronation Medal was a commemorative medal, instituted to celebrate the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

Issue

This medal was awarded as a personal souvenir of King George VI's coronation. It was awarded to th ...

. He was appointed a Privy Counsellor

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

in 1940 and a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour in 1946.

Notes

References

* * * * Clark, Margaret (editor) (1998). ''Peter Fraser: Master Politician''. Dunmore Press, Palmerston North (1997 symposium) * * McGibbon, Ian, ed. (1993). ''Undiplomatic Dialogue: Letters between Carl Berendsen and Alister McIntosh''. Auckland University Press, Auckland *External links

Prime Minister's Office biography

by Michael Bassett * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fraser, Peter Prime Ministers of New Zealand New Zealand Labour Party MPs New Zealand foreign ministers New Zealand Labour Party leaders World War II political leaders Scottish politicians Scottish emigrants to New Zealand People from Ross and Cromarty Politicians from Wellington City 1884 births 1950 deaths Leaders of the Opposition (New Zealand) Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives New Zealand education ministers New Zealand MPs for Wellington electorates New Zealand anti–World War I activists New Zealand politicians convicted of crimes New Zealand members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom New Zealand Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Social Democratic Party (New Zealand) politicians Burials at Karori Cemetery Wellington City Councillors Wellington Harbour Board members