Pentre Ifan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pentre Ifan (literally "Evan's Village") is the name of an ancient manor in the

The dolmen dates from around 3500 BC, and has traditionally been identified as a communal burial. Under this theory the existing stones formed the portal and main chamber of the tomb, which would originally have been covered by a large mound of stones about long and 17 m wide. Some of the kerbstones, marking the edge of the mound, have been identified during excavations. The stone chamber was at the southern end of the long mound, which stretched off to the north. Very little of the material that formed the mound remains. Some of the stones have been scattered, but at least seven are in their original position. An elaborate entrance façade surrounding the portal, which may have been a later addition,stonepages.com

The dolmen dates from around 3500 BC, and has traditionally been identified as a communal burial. Under this theory the existing stones formed the portal and main chamber of the tomb, which would originally have been covered by a large mound of stones about long and 17 m wide. Some of the kerbstones, marking the edge of the mound, have been identified during excavations. The stone chamber was at the southern end of the long mound, which stretched off to the north. Very little of the material that formed the mound remains. Some of the stones have been scattered, but at least seven are in their original position. An elaborate entrance façade surrounding the portal, which may have been a later addition,stonepages.com

Accessed 7 June 2014 was built with carefully constructed

First, such monuments typically have a large capstone derived from a glacial erratic, far bigger than is required or sensible if the aim is to roof a chamber. Furthermore, the capstone has a flat underside. Sometimes, as here, this has been arrived at by splitting the rock; at other sites, such as Garn Turne, some 12 km to the south-west, it has been laboriously 'pecked' off using stone tools. The capstone is supported on the tapering tips of slender uprights. As at Pentre Ifan, there are often other stones within the group, but they play no part in holding up the capstone, and the resulting effect of the enormous stone appearing to float above the other stones would seem to be deliberate and desired. If these are the key elements of the monument then, it is argued, the stones were never designed to be buried within a mound, and they never formed a chamber to contain bones. What we see today is the monument as it was intended to be seen. It might therefore represent a more elaborate version of a standing stone. Its purpose could be simply to demonstrate the status and skill of the builders, or to add significance and gravitas to an already significant place.

First, such monuments typically have a large capstone derived from a glacial erratic, far bigger than is required or sensible if the aim is to roof a chamber. Furthermore, the capstone has a flat underside. Sometimes, as here, this has been arrived at by splitting the rock; at other sites, such as Garn Turne, some 12 km to the south-west, it has been laboriously 'pecked' off using stone tools. The capstone is supported on the tapering tips of slender uprights. As at Pentre Ifan, there are often other stones within the group, but they play no part in holding up the capstone, and the resulting effect of the enormous stone appearing to float above the other stones would seem to be deliberate and desired. If these are the key elements of the monument then, it is argued, the stones were never designed to be buried within a mound, and they never formed a chamber to contain bones. What we see today is the monument as it was intended to be seen. It might therefore represent a more elaborate version of a standing stone. Its purpose could be simply to demonstrate the status and skill of the builders, or to add significance and gravitas to an already significant place.

Pentre Ifan was studied by early travellers and antiquarians, and rapidly became famous as an image of ancient Wales,

Pentre Ifan was studied by early travellers and antiquarians, and rapidly became famous as an image of ancient Wales,www.bluestonewales.com

accessed 7 June 2014 from engravings of the romantic stones. George Owen wrote of it in enthusiastic terms in 1603, and Richard Tongue painted it in 1835.

, accessed 7 June 2014 The first United Kingdom legislation to protect ancient monuments was passed in 1882, and 'The Pentre Evan Cromlech' (as it was styled) was on the initial list of 68 protected sites – one of only three in Wales. On 8 June 1884, two years after the passing of the first Ancient Monuments Act,

, Issue 108, Sep/Oct 2009 The legal protection the Act gave was limited. It became an offence to remove stones or items from the site, but the owner of a monument was exempt from any prosecution. The Act however provided for the Commissioner of Works to become 'guardian' of a scheduled monument – in effect to own the monument, even though the land on which it stood remained in private ownership. Perhaps as result of Pitt Rivers' visit, this protection was put in place, and the Commissioner of Works and his various successor bodies have been guardians of Pentre Ifan ever since. Archaeological excavations took place in 1936–37 and 1958–59, both led by William Francis Grimes. This identified rows of ritual pits which lay under the mound, and therefore must predate it. Kerbstones for the mound were also found, but not in a complete sequence, and aligned more to the pits than to the stone chamber. Very few items were found in the excavations, other than some flint flakes, and a small amount of Welsh (Western) pottery. The dolmen is maintained and cared for by Cadw, the Welsh Historic Monuments Agency. The site is well kept, and entrance is free. It is about from Cardigan, and east of

File:PentreIfanH1a.jpg

File:PentreIfanH2a.jpg

File:PentreIfanH3a.jpg

File:PentreIfanH4a.jpg

Photos of Pentre Ifan and surrounding area

geograph.org; accessed June 4, 2020.

* ttp://www.newportpembs.co.uk/articles/pentreifan-newport-pembs.php Article and photos of Pentre Ifan

Images

megalithic.co.uk; accessed June 4, 2020. {{European Standing Stones 4th-millennium BC architecture Prehistoric sites in Pembrokeshire Dolmens in Wales Buildings and structures in Pembrokeshire Monuments and memorials in Pembrokeshire

community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, tow ...

and parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

of Nevern

Nevern ( cy, Nanhyfer) is both a parish and a community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. The community includes the settlements of Felindre Farchog, Monington, Moylgrove and Bayvil. The small village lies in the Nevern valley near the Preseli Hills of ...

, Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. It is from Cardigan, Ceredigion, and east of Newport, Pembrokeshire

Newport ( cy, Trefdraeth, meaning: "town by the beach") is a town, parish, community, electoral ward and ancient port of ''Parrog'', on the Pembrokeshire coast in West Wales at the mouth of the River Nevern ( cy, Afon Nyfer) in the Pembrokeshire ...

. Pentre Ifan contains and gives its name to the largest and best preserved neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

dolmen

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were somet ...

in Wales.

The Pentre Ifan monument is a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

and is one of three Welsh monuments to have received legal protection under the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882

The Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (as it then was). It was introduced by John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury, recognising the need for a governmental administrat ...

. The dolmen is maintained and cared for by Cadw, the Welsh Historic Monuments Agency.

Toponymy

cy, Pentre Ifan translates to "Ifan's village" – from '' pentref'' – ''pen'' head, and ''tref'' town.The monument

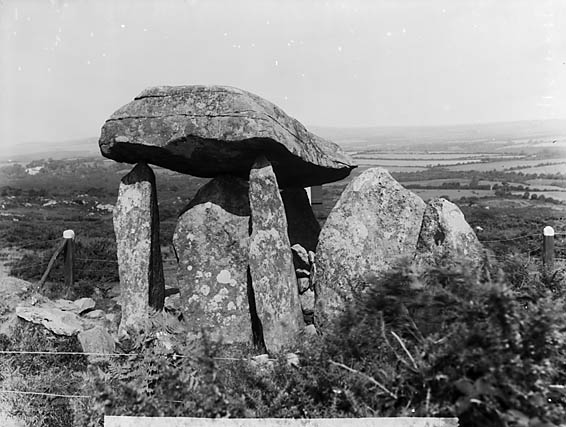

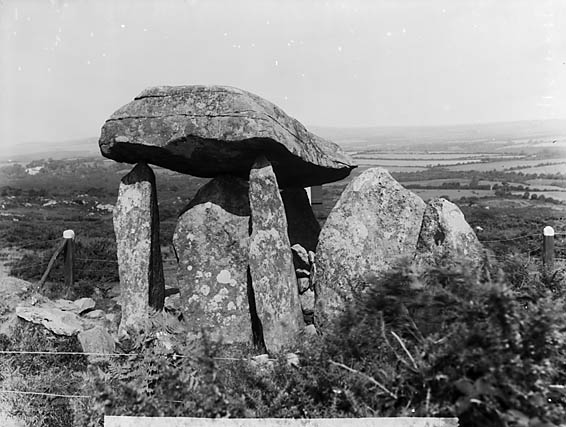

As it now stands, the Pentre Ifan Dolmen is a collection of seven principal stones. The largest is the huge capstone, long, width and thick. It is estimated to weigh 16 tonnes and rests on the tips of three other stones, some off the ground. There are six upright stones, three of which support the capstone. Of the remaining three, two portal stones form an entrance and the third, at an angle, appears to block the doorway.Original use

The dolmen dates from around 3500 BC, and has traditionally been identified as a communal burial. Under this theory the existing stones formed the portal and main chamber of the tomb, which would originally have been covered by a large mound of stones about long and 17 m wide. Some of the kerbstones, marking the edge of the mound, have been identified during excavations. The stone chamber was at the southern end of the long mound, which stretched off to the north. Very little of the material that formed the mound remains. Some of the stones have been scattered, but at least seven are in their original position. An elaborate entrance façade surrounding the portal, which may have been a later addition,stonepages.com

The dolmen dates from around 3500 BC, and has traditionally been identified as a communal burial. Under this theory the existing stones formed the portal and main chamber of the tomb, which would originally have been covered by a large mound of stones about long and 17 m wide. Some of the kerbstones, marking the edge of the mound, have been identified during excavations. The stone chamber was at the southern end of the long mound, which stretched off to the north. Very little of the material that formed the mound remains. Some of the stones have been scattered, but at least seven are in their original position. An elaborate entrance façade surrounding the portal, which may have been a later addition,stonepages.comAccessed 7 June 2014 was built with carefully constructed

dry stone wall

Dry stone, sometimes called drystack or, in Scotland, drystane, is a building method by which structures are constructed from stones without any mortar to bind them together. Dry stone structures are stable because of their construction m ...

ing. Individual burials are thought to have been made within the stone chamber, which would be re-used many times. No traces of bones were found in the tomb, raising the possibility that they were subsequently transferred elsewhere.

Alternative theory

A major study by Cummings and Richards in 2014 produced a different explanation for the monument. They identify several distinctive attributes shared by the class of monument known as dolmens, all of which are particularly well exemplified at Pentre Ifan. First, such monuments typically have a large capstone derived from a glacial erratic, far bigger than is required or sensible if the aim is to roof a chamber. Furthermore, the capstone has a flat underside. Sometimes, as here, this has been arrived at by splitting the rock; at other sites, such as Garn Turne, some 12 km to the south-west, it has been laboriously 'pecked' off using stone tools. The capstone is supported on the tapering tips of slender uprights. As at Pentre Ifan, there are often other stones within the group, but they play no part in holding up the capstone, and the resulting effect of the enormous stone appearing to float above the other stones would seem to be deliberate and desired. If these are the key elements of the monument then, it is argued, the stones were never designed to be buried within a mound, and they never formed a chamber to contain bones. What we see today is the monument as it was intended to be seen. It might therefore represent a more elaborate version of a standing stone. Its purpose could be simply to demonstrate the status and skill of the builders, or to add significance and gravitas to an already significant place.

First, such monuments typically have a large capstone derived from a glacial erratic, far bigger than is required or sensible if the aim is to roof a chamber. Furthermore, the capstone has a flat underside. Sometimes, as here, this has been arrived at by splitting the rock; at other sites, such as Garn Turne, some 12 km to the south-west, it has been laboriously 'pecked' off using stone tools. The capstone is supported on the tapering tips of slender uprights. As at Pentre Ifan, there are often other stones within the group, but they play no part in holding up the capstone, and the resulting effect of the enormous stone appearing to float above the other stones would seem to be deliberate and desired. If these are the key elements of the monument then, it is argued, the stones were never designed to be buried within a mound, and they never formed a chamber to contain bones. What we see today is the monument as it was intended to be seen. It might therefore represent a more elaborate version of a standing stone. Its purpose could be simply to demonstrate the status and skill of the builders, or to add significance and gravitas to an already significant place.

Construction technique

The sheer size of the huge capstone that is supported by the larger dolmens makes it overwhelmingly likely that the stone was not brought in from elsewhere, but already stood as an independentglacial erratic

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundre ...

on the same spot it now occupies. Evidence from the 1948 excavation is compatible with the idea of a large pit being dug at Pentre Ifan, to expose and work on the stone, perhaps splitting it to create a flat underside, It could then be levered vertically upwards a little at a time, using poles, ropes, and large numbers of people, and packed into place using a growing heap of boulders. Once at the required height, the supporting uprights could be introduced, and the boulders removed to leave only the uprights, and such other surrounding stones as were wanted.or for sacrificial ceremonies

Archaeology

accessed 7 June 2014

, accessed 7 June 2014 The first United Kingdom legislation to protect ancient monuments was passed in 1882, and 'The Pentre Evan Cromlech' (as it was styled) was on the initial list of 68 protected sites – one of only three in Wales. On 8 June 1884, two years after the passing of the first Ancient Monuments Act,

Augustus Pitt Rivers

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers (14 April 18274 May 1900) was an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist. He was noted for innovations in archaeological met ...

, Britain's first Inspector of Ancient Monuments, made a visit and produced sketch plans of the monument.''British Archaeology'' Magazine: News, Issue 108, Sep/Oct 2009 The legal protection the Act gave was limited. It became an offence to remove stones or items from the site, but the owner of a monument was exempt from any prosecution. The Act however provided for the Commissioner of Works to become 'guardian' of a scheduled monument – in effect to own the monument, even though the land on which it stood remained in private ownership. Perhaps as result of Pitt Rivers' visit, this protection was put in place, and the Commissioner of Works and his various successor bodies have been guardians of Pentre Ifan ever since. Archaeological excavations took place in 1936–37 and 1958–59, both led by William Francis Grimes. This identified rows of ritual pits which lay under the mound, and therefore must predate it. Kerbstones for the mound were also found, but not in a complete sequence, and aligned more to the pits than to the stone chamber. Very few items were found in the excavations, other than some flint flakes, and a small amount of Welsh (Western) pottery. The dolmen is maintained and cared for by Cadw, the Welsh Historic Monuments Agency. The site is well kept, and entrance is free. It is about from Cardigan, and east of

Newport, Pembrokeshire

Newport ( cy, Trefdraeth, meaning: "town by the beach") is a town, parish, community, electoral ward and ancient port of ''Parrog'', on the Pembrokeshire coast in West Wales at the mouth of the River Nevern ( cy, Afon Nyfer) in the Pembrokeshire ...

.

See also

*List of Scheduled prehistoric Monuments in north Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire is the fifth-largest county in Wales, but has more scheduled monuments (526) than any except Powys. This gives it an extremely high density of monuments, with 33.4 per 100 km2. (Only the tiny county boroughs of List of schedul ...

* Archaeology of Wales

The archaeology of Wales (Welsh: ''Archaeoleg Cymru'') is the study of human occupation within the country of Wales which has been occupied by modern humans since 225,000 BCE, with continuous occupation from 9,000 BCE. Analysis of the sites, arte ...

* Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connectin ...

References

External links

Photos of Pentre Ifan and surrounding area

geograph.org; accessed June 4, 2020.

* ttp://www.newportpembs.co.uk/articles/pentreifan-newport-pembs.php Article and photos of Pentre Ifan

Images

megalithic.co.uk; accessed June 4, 2020. {{European Standing Stones 4th-millennium BC architecture Prehistoric sites in Pembrokeshire Dolmens in Wales Buildings and structures in Pembrokeshire Monuments and memorials in Pembrokeshire