Peltasts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A ''peltast'' ( grc-gre, πελταστής ) was a type of light infantryman, originating in

In the Archaic period, the Greek martial tradition had been focused almost exclusively on the heavy infantry, or hoplites.

The style of fighting used by ''peltasts'' originated in

In the Archaic period, the Greek martial tradition had been focused almost exclusively on the heavy infantry, or hoplites.

The style of fighting used by ''peltasts'' originated in

''Peltasts'' were usually deployed on the flanks of the

''Peltasts'' were usually deployed on the flanks of the

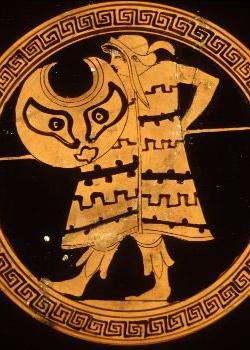

Picture of a peltast

{{Ancient Greece topics Military units and formations of ancient Greece Military units and formations of the Hellenistic world Ancient Greek infantry types Infantry Mercenary units and formations of antiquity Infantry units and formations of Macedon Combat occupations

Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and Paeonia, and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

in the Anabasis distinguishes the Thracian and Greek peltast troops.

The peltast often served as a skirmisher in Hellenic and Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

armies. In the Medieval period, the same term was used for a type of Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

infantryman.

Description

''Pelte'' shield

''Peltasts'' carried a crescent-shapedwicker

Wicker is the oldest furniture making method known to history, dating as far back as 5,000 years ago. It was first documented in ancient Egypt using pliable plant material, but in modern times it is made from any pliable, easily woven material. ...

shield called a "''pelte''" (Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

grc, πέλτη, peltē, label=none; Latin: ) as their main protection, hence their name. According to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, the ''pelte'' was rimless and covered in goat- or sheepskin. Some literary sources imply that the shield could be round, but in art it is usually shown as crescent-shaped. It also appears in Scythian art and may have been a common type in Central Europe. The shield could be carried with a central strap and a handgrip near the rim or with just a central hand-grip. It may also have had a carrying strap (or '' guige''), as Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

''peltasts'' slung their shields on their backs when evading the enemy.

Weapons

''Peltasts'' weapons consisted of several javelins, which may have had straps to allow more force to be applied to a throw.Development

Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, and the first Greek ''peltasts'' were recruited from the Greek cities of the Thracian coast. They are generally depicted on vases and in other images as wearing the typical Thracian costume, which includes the distinctive Phrygian cap made of fox-skin and with ear flaps. They also usually wore patterned tunics, fawnskin boots and long cloaks, called ''zeiras'', decorated with a bright, geometric, pattern. However, many mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

''peltasts'' were probably recruited in Greece. Some vases have also been found showing hoplites (men wearing Corinthian helmet

The Corinthian helmet originated in ancient Greece and took its name from the city-state of Corinth. It was a helmet made of bronze which in its later styles covered the entire head and neck, with slits for the eyes and mouth. A large curved pr ...

s, greaves and cuirasses, holding hoplite spears) carrying ''peltes''. Often, the mythical Amazons

In Greek mythology, the Amazons (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνες ''Amazónes'', singular Ἀμαζών ''Amazōn'', via Latin ''Amāzon, -ŏnis'') are portrayed in a number of ancient epic poems and legends, such as the Labours of Hercule ...

(women warriors) are shown with ''peltast'' equipment.

''Peltasts'' gradually became more important in Greek warfare, in particular during the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

.

Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, in the '' Anabasis'', describes ''peltasts'' in action against Persian cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

at the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BC, where they were serving as part of the mercenary force of Cyrus the Younger

Cyrus the Younger ( peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ''Kūruš''; grc-gre, Κῦρος ; died 401 BC) was an Achaemenid prince and general. He ruled as satrap of Lydia and Ionia from 408 to 401 BC. Son of Darius II and Parysatis, he died in 401 BC i ...

. Xenophon's description makes it clear that these ''peltasts'' were armed with swords, as well as javelins, but not with spears. When faced with a charge from the Persian cavalry, they opened their ranks and allowed the cavalry through while striking them with swords and hurling javelins at them.Xenophon. ''Anabasis''.Tissaphernes Tissaphernes ( peo, *Ciçafarnāʰ; grc-gre, Τισσαφέρνης; xlc, 𐊋𐊆𐊈𐊈𐊀𐊓𐊕𐊑𐊏𐊀 , ; 445395 BC) was a Persian soldier and statesman, Satrap of Lydia and Ionia. His life is mostly known from the works of Thuc ...had not fled at the first charge (by the Greek troops), but had instead charged along the river through the Greek ''peltasts''. However he did not kill a single man as he passed through. The Greeks opened their ranks (to allow the Persian cavalry through) and proceeded to deal blows (with swords) and throw javelins at them as they went through.

.10.7

Tenth may refer to:

Numbers

* 10th, the ordinal form of the number ten

* One tenth, , or 0.1, a fraction, one part of a unit divided equally into ten parts.

** the SI prefix deci-

** tithe, a one-tenth part of something

* 1/10 of any unit of me ...

''Peltasts'' became the main type of Greek mercenary infantry in the 4th century BC. Their equipment was less expensive than that of traditional hoplites and would have been more readily available to poorer members of society. The Athenian general Iphicrates

Iphicrates ( grc-gre, Ιφικράτης; c. 418 BC – c. 353 BC) was an Athenian general, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC. He is credited with important infantry reforms that revolutionized ancient Greek warfare by ...

destroyed a Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

n phalanx in the Battle of Lechaeum

The Battle of Lechaeum (391 BC) was an Athenian victory in the Corinthian War. In the battle, the Athenian general Iphicrates took advantage of the fact that a Spartan hoplite regiment operating near Corinth was moving in the open without the pr ...

in 390 BC, using mostly ''peltasts''. In the account of Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, Iphicrates

Iphicrates ( grc-gre, Ιφικράτης; c. 418 BC – c. 353 BC) was an Athenian general, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC. He is credited with important infantry reforms that revolutionized ancient Greek warfare by ...

is credited with re-arming his men with long spears, perhaps in around 374 BC. This reform may have produced a type of "''peltast''" armed with a small shield, a sword, and a spear instead of javelins.

Some authorities, such as J.G.P. Best, state that these later "''peltasts''" were not truly ''peltasts'' in the traditional sense, but lightly armored hoplites carrying the ''pelte'' shield in conjunction with longer spears—a combination that has been interpreted as a direct ancestor to the Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx ( gr, Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6 meter pike. It was famously commanded ...

.Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XV.44 However, thrusting spears are included on some illustrations of ''peltasts'' before the time of Iphicrates and some ''peltasts'' may have carried them as well as javelins rather than as a replacement for them. As no battle accounts actually describe ''peltasts'' using thrusting spears, it may be that they were sometimes carried by individuals by choice (rather than as part of a policy or reform). The Lykian sarcophagas of Payava from about 400 BC depicts a soldier carrying a round ''pelte'', but using a thrusting spear overarm. He wears a '' pilos'' helmet with cheekpieces, but no armour. His equipment therefore resembles Iphicrates's supposed new troops. Fourth-century BC ''peltasts'' also seem to have sometimes worn both helmets and linen armour.

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

employed ''peltasts'' drawn from the Thracian tribes to the north of Macedonia, particularly the Agrianoi. In the 3rd century BC, ''peltasts'' were gradually replaced with ''thureophoroi

The ''thyreophoroi'' or ''thureophoroi'' ( el, θυρεοφόροι; singular: ''thureophoros''/''thyreophoros'', θυρεοφόρος) were a type of infantry soldier, common in the 3rd to 1st centuries BC, who carried a large oval shield called a ...

'' infantrymen. Later references to ''peltasts'' may not in fact refer to their style of equipment as the word ''peltast'' became a synonym for ''mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

''.

Anatolian

A tradition of fighting with javelins, light shield and sometimes a spear existed inAnatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and several contingents armed like this appeared in Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

's army that invaded Greece in 480 BC. For example, the Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

ns and Phrygians wore wicker helmets and native boots reaching halfway to the knee. They carried small shields, short spears, javelins and daggers.

In the Persian army

From the mid-5th century BC onwards, ''peltast'' soldiers began to appear in Greek depictions of Persian troops. They were equipped like Greek and Thracian ''peltasts'', but were dressed in typically Persian army uniforms. They often carried light axes, known as '' sagaris'', as sidearms. It has been suggested that these troops were known in Persian as ''takabara Takabara was a unit in the Persian Achaemenid army. They appear in some references related to the Greco-Persian wars, but little is known about them. According to Greek sources they were a tough type of peltasts.Nicholas Sekunda, ''The Persian Army ...

'' and their shields as ''taka''. The Persians may have been influenced by Greek and Thracian ''peltasts''. Another alternative source of influence would have been the Anatolian hill tribes, such as the Corduene

Corduene hy, Կորճայք, translit=Korchayk; ; romanized: ''Kartigini'') was an ancient historical region, located south of Lake Van, present-day eastern Turkey.

Many believe that the Kardouchoi—mentioned in Xenophon’s Anabasis as havin ...

, Mysians

Mysians ( la, Mysi; grc, Μυσοί, ''Mysoí'') were the inhabitants of Mysia, a region in northwestern Asia Minor.

Origins according to ancient authors

Their first mention is by Homer, in his list of Trojans allies in the Iliad, and accordin ...

or Pisidia

Pisidia (; grc-gre, Πισιδία, ; tr, Pisidya) was a region of ancient Asia Minor located north of Pamphylia, northeast of Lycia, west of Isauria and Cilicia, and south of Phrygia, corresponding roughly to the modern-day province of Ant ...

ns. In Greek sources, these troops were either called ''peltasts'' or ''peltophoroi'' (bearers of ''pelte'').

In the Antigonid army

In theHellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, the Antigonid

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

kings of Macedon had an elite corps of native Macedonian ''peltasts''. However, this force should not be confused with the skirmishing ''peltasts'' discussed earlier. The ''peltasts'' were probably, according to F.W. Walbank, about 3,000 in number, although by the Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) was a war fought between the Roman Republic and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC, King Philip V of Macedon died and was succeeded by his ambitious son Perseus. He was anti-Roman and stirred anti-Roman ...

, this went up to 5,000 (most likely to accommodate the elite ''agema

Agema ( el, Ἄγημα) is a term to describe a military detachment, used for a special cause, such as guarding high valued targets. Due to its nature the ''Agema'' most probably comprised elite troops.

Etymology

The word derives from the Greek ...

'', which was a sub-unit in the ''peltast'' corps). The fact that they are always mentioned as being in their thousands suggests that, in terms of organization, the ''peltasts'' were organized into '' chiliarchies''. This elite corps was most likely of the same status, of similar equipment and role as Alexander the Great's '' hypaspists''. Within this corps of ''peltasts'' was its elite formation, the Agema

Agema ( el, Ἄγημα) is a term to describe a military detachment, used for a special cause, such as guarding high valued targets. Due to its nature the ''Agema'' most probably comprised elite troops.

Etymology

The word derives from the Greek ...

. These troops were used on forced marches by Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon a ...

, which suggests that they were lightly equipped and mobile. However, at the battle of Pydna

The Battle of Pydna took place in 168 BC between Rome and Macedon during the Third Macedonian War. The battle saw the further ascendancy of Rome in the Hellenistic world and the end of the Antigonid line of kings, whose power traced back ...

in 168 BC, Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

remarks on how the Macedonian ''peltasts'' defeated the Paeligni

The Paeligni or Peligni were an Italic tribe who lived in the Valle Peligna, in what is now Abruzzo, central Italy.

History

The Paeligni are first mentioned as a member of a confederacy that included the Marsi, Marrucini, and Vestini, with which ...

and of how this shows the dangers of going directly at the front of a phalanx. Though it may seem strange for a unit that would fight in phalanx formation to be called ''peltasts'', ''pelte'' would not be an inappropriate name for a Macedonian shield. They may have been similarly equipped with the Iphicratean hoplites or ''peltasts'', as described by Diodorus.

Deployment

''Peltasts'' were usually deployed on the flanks of the

''Peltasts'' were usually deployed on the flanks of the phalanx

The phalanx ( grc, φάλαγξ; plural phalanxes or phalanges, , ) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar pole weapons. The term is particularly ...

, providing a link with any cavalry, or in rough or broken ground. For example, in the ''Hellenica

''Hellenica'' ( grc, Ἑλληνικά) simply means writings on Greek (Hellenic) subjects. Several histories of 4th-century Greece, written in the mould of Thucydides or straying from it, have borne the conventional Latin title ''Hellenica''. Th ...

'', Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

writes 'When Dercylidas learned this (that a Persian army was nearby), he ordered his officers to form their men in line, eight ranks deep (the hoplite phalanx), as quickly as possible, and to station the ''peltasts'' on either wing along with the cavalry. They could also operate in support of other light troops, such as archers and slingers.

Tactics

When faced with hoplites, ''peltasts'' operated by throwing javelins at short range. If the hoplites charged, the ''peltasts'' would retreat. As they carried considerably lighter equipment than the hoplites, they were usually able to evade successfully, especially in difficult terrain. They would then return to the attack once the pursuit ended, if possible, taking advantage of any disorder created in the hoplites' ranks. At theBattle of Sphacteria

The Battle of Sphacteria was a land battle of the Peloponnesian War, fought in 425 BC between Athens and Sparta. Following the Battle of Pylos and subsequent peace negotiations, which failed, a number of Spartans were stranded on the island of ...

, the Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

forces included 800 archers and at least 800 ''peltasts''. Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, in the ''History of the Peloponnesian War

The ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' is a historical account of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), which was fought between the Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) and the Delian League (led by Athens). It was written by Thucydides, an ...

'', writes They (the Spartan hoplites) themselves were held up by the weapons shot at them from both flanks by the light troops. Though they (the hoplites) drove back the light troops at any point in which they ran in and approached too closely, they (the light troops) still fought back even in retreat, since they had no heavy equipment and could easily outdistance their pursuers over ground where, since the place had been uninhabited until then, the going was rough and difficult.When fighting other types of light troops, ''peltasts'' were able to close more aggressively in

melee

A melee ( or , French: mêlée ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

, as they had the advantage of possessing shields, swords, and helmets.

Medieval Byzantine

A type of infantryman called a ''peltast'' (''peltastēs'') is described in the ''Strategikon'', a 6th-century AD military treatise associated with the earlyByzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

emperor Maurice. ''Peltasts'' were especially prominent in the Byzantine army of the Komnenian period

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Komnenos dynasty for a period of 104 years, from 1081 to about 1185. The ''Komnenian'' (also spelled ''Comnenian'') period comprises the reigns of five emperors, Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, A ...

in the late 11th and 12th centuries. Although the ''peltasts'' of Antiquity were light skirmish infantry armed with javelins, it is not safe to assume that the troops given this name in the Byzantine period were identical in function. Byzantine ''peltasts'' were sometimes described as "assault troops". Byzantine ''peltasts'' appear to have been relatively lightly equipped soldiers capable of great battlefield mobility, who could skirmish but who were equally capable of close combat. Their arms may have included a shorter version of the ''kontarion'' spear employed by contemporary Byzantine heavy infantry.Dawson, p. 59.

See also

*Ancient Macedonian military

The army of the Kingdom of Macedon was among the greatest military forces of the ancient world. It was created and made formidable by King Philip II of Macedon; previously the army of Macedon had been of little account in the politics of the G ...

*Toxotai

Toxotai (; singular: , ) were Ancient Greek and Byzantine archers.

During the ancient period they were armed with a short Greek bow and a short sword. They carried a little pelte (or pelta) () shield.

''Hippotoxotai'' (ἱπποτοξόται ...

*Velites

''Velites'' (singular: ) were a class of infantry in the Roman army of the mid-Republic from 211 to 107 BC. ''Velites'' were light infantry and skirmishers armed with javelins ( la, hastae velitares), each with a 75cm (30 inch) wooden shaft the ...

*Takabara Takabara was a unit in the Persian Achaemenid army. They appear in some references related to the Greco-Persian wars, but little is known about them. According to Greek sources they were a tough type of peltasts.Nicholas Sekunda, ''The Persian Army ...

References

Bibliography

*Best, J. G. P. (1969). ''Thracian Peltasts and their influence on Greek warfare''. * * Connolly, Peter (1981). ''Greece and Rome at War''. Macdonald (Black Cat, 1988). * *Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

. History.

*Head, Duncan (1982). ''Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars''. WRG.

*Head, Duncan (1992). ''The Achaemenid Persian Army''. Montvert.

*Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

.'' The Histories''

*"Light Infantry", special issue of ''Ancient Warfare

Ancient warfare is war that was conducted from the beginning of recorded history to the end of the ancient period. The difference between prehistoric and ancient warfare is more organization oriented than technology oriented. The development of ...

'', 2/1 (2008)

*Sekunda, Nicholas V (1988). ''Achaemenid Military Terminology''. Arch. Mitt. aus Iran 21

*Sekunda, N (1992). ''The Persian Army 560–330 BC''. Osprey.

*Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

. '' The History of the Peloponnesian War''.

*Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

. '' Anabasis''.

*Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

. ''Hellenica

''Hellenica'' ( grc, Ἑλληνικά) simply means writings on Greek (Hellenic) subjects. Several histories of 4th-century Greece, written in the mould of Thucydides or straying from it, have borne the conventional Latin title ''Hellenica''. Th ...

''.

External links

Picture of a peltast

{{Ancient Greece topics Military units and formations of ancient Greece Military units and formations of the Hellenistic world Ancient Greek infantry types Infantry Mercenary units and formations of antiquity Infantry units and formations of Macedon Combat occupations