Pays des Illinois on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of

The boundaries of the Illinois Country were defined in a variety of ways, but the region now known as the

The boundaries of the Illinois Country were defined in a variety of ways, but the region now known as the

The first French explorations of the Illinois Country were in the first half of the 17th century, led by explorers and missionaries based in Canada.

The first French explorations of the Illinois Country were in the first half of the 17th century, led by explorers and missionaries based in Canada.

Illinois State MuseumJacques Marquette 1673 , Virtual Museum of New France

Canadian Museum of History By 1714, the principal European, non-native inhabitants were ''

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to  The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the aggressive Fox Indians. The fort was named after Louis, duc de Chartres, son of the regent of France. Because of frequent flooding, another fort was built further inland in 1725. By 1731, the Company of the Indies had gone defunct and turned Louisiana and its government back to the king. The garrison at the fort was removed to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1747, about 18 miles to the south. A new stone fort was planned near the old fort and was described as "nearly complete" in 1754, although construction continued until 1760.

The new stone fort was headquarters for the French Illinois Country for less than 20 years, as it was turned over to the British in 1763 with the

The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the aggressive Fox Indians. The fort was named after Louis, duc de Chartres, son of the regent of France. Because of frequent flooding, another fort was built further inland in 1725. By 1731, the Company of the Indies had gone defunct and turned Louisiana and its government back to the king. The garrison at the fort was removed to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1747, about 18 miles to the south. A new stone fort was planned near the old fort and was described as "nearly complete" in 1754, although construction continued until 1760.

The new stone fort was headquarters for the French Illinois Country for less than 20 years, as it was turned over to the British in 1763 with the

* Peoria was at first the southernmost part of

* Peoria was at first the southernmost part of  *

*

During the Revolutionary War, General George Rogers Clark took possession of the part of the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi for

During the Revolutionary War, General George Rogers Clark took possession of the part of the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi for

online

*Belting, Natalia Maree, ''Kaskaskia under the French Regime'' (1948

online

*Brackenridge, Henri Marie, ''Recollections of Persons and Places in the West'' (Google Books) *Ekberg, Carl J., ''Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country'', Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007. *Ekberg, Carl J., ''Francois Vallé and His World: Upper Louisiana Before Lewis and Clark'', Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2002. *Ekberg, Carl J., ''French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times'', Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000, *Ekberg, Carl J., ''Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier'', Tucson, AZ: Patrice Press, 1996, * Lippincott, Isaac. "Industry among the French in the Illinois country." ''Journal of Political Economy'' 18.2 (1910): 114-128

online

Library of Congress exhibit

Louisiana Digital Libraries

Plan for Fort Orleans {{Authority control 1699 establishments in New France 1765 disestablishments in New France Former French colonies Louisiana (New France) Pre-statehood history of Illinois Pre-statehood history of Indiana Pre-statehood history of Kentucky Pre-statehood history of Ohio Pre-statehood history of Missouri Former territorial entities in North America

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

claimed in the 1600s in what is now the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

. While these names generally referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River

The Upper Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River upstream of St. Louis, Missouri, United States, at the confluence of its main tributary, the Missouri River.

History

In terms of geologic and hydrographic history, the Upper ...

watershed, French colonial settlement was concentrated along the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Illinois Rivers in what is now the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, with outposts in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

. Explored in 1673 from Green Bay to the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

by the ''Canadien

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

'' expedition of Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore and ...

and Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

, the area was claimed by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. It was settled primarily from the ''Pays d'en Haut

The ''Pays d'en Haut'' (; ''Upper Country'') was a territory of New France covering the regions of North America located west of Montreal. The vast territory included most of the Great Lakes region, expanding west and south over time into the ...

'' in the context of the fur trade, and in the establishment of missions by French Catholic religious orders. Over time, the fur trade took some French to the far reaches of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

, especially along the branches of the broad Missouri River valley. The French name, ''Pays

In France, a ''pays'' () is an area whose inhabitants share common geographical, economic, cultural, or social interests, who have a right to enter into communal planning contracts under a law known as the Loi Pasqua or LOADT (''Loi d'Orientation ...

des Ilinois'', means "Land of the Illinois lural and is a reference to the Illinois Confederation

The Illinois Confederation, also referred to as the Illiniwek or Illini, were made up of 12 to 13 tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley. Eventually member tribes occupied an area reaching from Lake Michicigao (Michigan) to Iowa, Ill ...

, a group of related Algonquian native peoples.

Up until 1717, the Illinois Country was governed by the French province of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, but by order of King Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

, the Illinois Country was annexed to the French province of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, with the northeastern administrative border being somewhat vaguely on or near the upper Illinois River. The territory thus became known as "Upper Louisiana." By the mid-18th century, the major settlements included Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south- ...

, Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

, Chartres, Saint Philippe, and Prairie du Rocher, all on the east side of the Mississippi in present-day Illinois; and Ste. Genevieve across the river in Missouri, as well as Fort Vincennes in what is now Indiana.

As a consequence of the French defeat in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

in 1764, the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River was ceded to the British and became part of the British Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

; the land west of the river was ceded to the Spanish ('' Luisiana'').

During the American Revolution, Virginian George Rogers Clark led the Illinois campaign

The Illinois campaign, also known as Clark's Northwestern campaign (1778–1779), was a series of events during the American Revolutionary War in which a small force of Virginia militiamen, led by George Rogers Clark, seized control of several B ...

against the British. Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River along with what was then much of Ohio Country, became part of Illinois County, Virginia

Illinois County, Virginia, was a political and geographic region, part of the British Province of Quebec, claimed during the American Revolutionary War on July 4, 1778 by George Rogers Clark of the Virginia Militia, as a result of the Illinois ...

, claimed by right of conquest. The county was abolished in 1782. In 1784, Virginia ceded its claims. Part of the area was incorporated in the United States' Northwest Territory. The name lived on as Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. Its ...

between 1809 and 1818, and as the State of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

after its admission to the union in 1818. The residual part of Illinois Country west of the Mississippi was acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

in 1803.

Location and boundaries

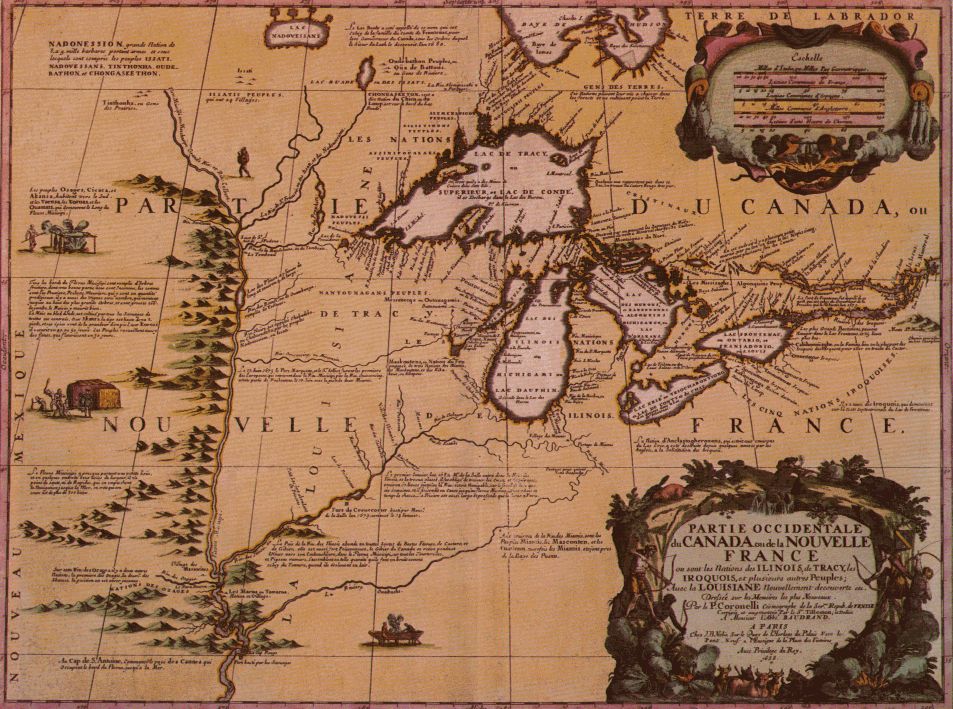

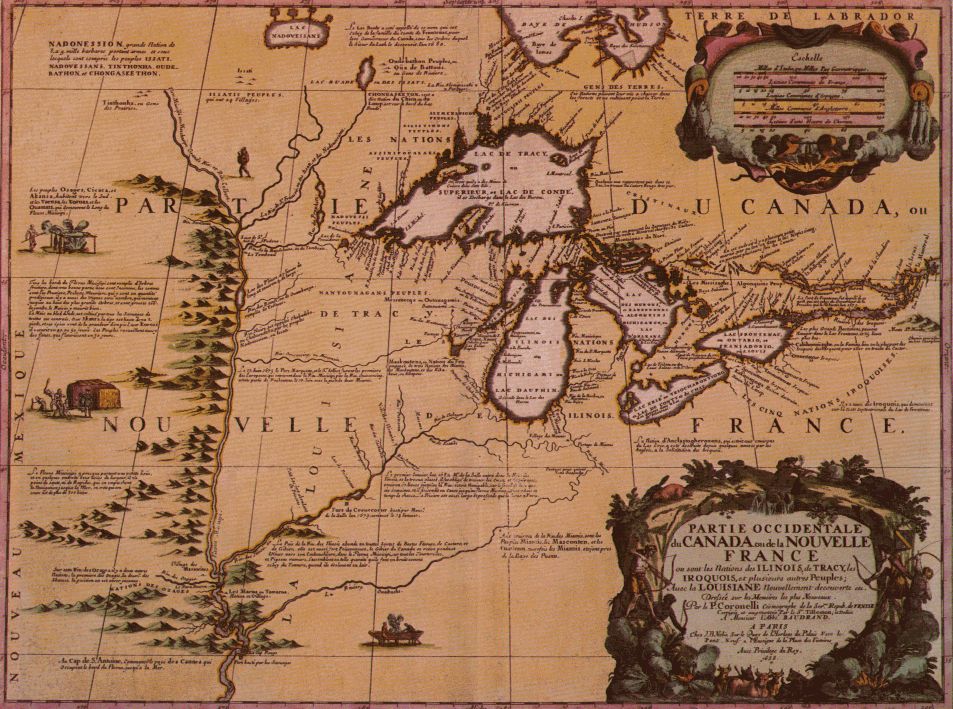

The boundaries of the Illinois Country were defined in a variety of ways, but the region now known as the

The boundaries of the Illinois Country were defined in a variety of ways, but the region now known as the American Bottom

The American Bottom is the flood plain of the Mississippi River in the Metro-East region of Southern Illinois, extending from Alton, Illinois, south to the Kaskaskia River. It is also sometimes called "American Bottoms". The area is about , mo ...

was nearly at the center of all descriptions. One of the earliest known geographic features designated as ''Ilinois'' was what later became known as Lake Michigan, on a map prepared in 1671 by French Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

. Early French missionaries and traders referred to the area southwest and southeast of the lake, including much of the upper Mississippi Valley, by this name. ''Illinois'' was also the name given to an area inhabited by the Illiniwek

The Illinois Confederation, also referred to as the Illiniwek or Illini, were made up of 12 to 13 tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley. Eventually member tribes occupied an area reaching from Lake Michicigao (Michigan) to Iowa, Ill ...

. A map of 1685 labels a large area southwest of the lake ''les Ilinois''; in 1688, the Italian cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli (August 16, 1650 – December 9, 1718) was an Italian Franciscan friar, cosmographer, cartographer, publisher, and encyclopedist known in particular for his atlases and globes. He spent most of his life in Venice.

Biog ...

labeled the region (in Italian) as ''Illinois country.'' In 1721, the seventh civil and military district of Louisiana was named ''Illinois''. It included more than half of the present state, as well as the land between the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

and the line of 43 degrees north latitude, and the country between the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

and the Mississippi River. A royal ordinance of 1722—following the transfer of the Illinois Country's governance from Canada to Louisiana—may have featured the broadest definition of the region: all land claimed by France south of the Great Lakes and north of the mouth of the Ohio River, which would include the lower Missouri Valley as well as both banks of the Mississippi.

A generation later, trade conflicts between Canada and Louisiana led to a more defined boundary between the French colonies; in 1745, Louisiana governor general Vaudreuil set the northeastern bounds of his domain as the Wabash valley up to the mouth of the Vermilion River (near present-day Danville, Illinois

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Vermilion County, Illinois. As of the 2010 census, its population was 33,027. As of 2019, the population was an estimated 30,479.

History

The area that is now Danville was once home to the Miami, K ...

); from there, northwest to ''le Rocher'' on the Illinois River, and from there west to the mouth of the Rock River (at present day Rock Island, Illinois). Thus, Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

and Peoria were near the limit of Louisiana's reach; the outposts at Ouiatenon

Ouiatenon ( mia, waayaahtanonki) was a dwelling place of members of the Wea tribe of Native Americans. The name ''Ouiatenon'', also variously given as ''Ouiatanon'', ''Oujatanon'', ''Ouiatano'' or other similar forms, is a French rendering of ...

(on the upper Wabash near present-day Lafayette, Indiana

Lafayette ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, located northwest of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette, on the other side of the Wabash River, is home to Purdue University, whi ...

), Checagou, Fort Miamis (near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

) and Prairie du Chien

Prairie du Chien () is a city in and the county seat of Crawford County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 5,506 at the 2020 census. Its ZIP Code is 53821.

Often referred to as Wisconsin's second oldest city, Prairie du Chien was esta ...

operated as dependencies of Canada.

This boundary between Canada and the Illinois Country remained in effect until the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

in 1763, after which France surrendered its remaining territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain. (Although British forces had occupied the "Canadian" posts in the Illinois and Wabash countries in 1761, they did not occupy Vincennes or the Mississippi River settlements at Cahokia and Kaskaskia until 1764, after the ratification of the peace treaty.) As part of a general report on conditions in the newly conquered lands, Gen. Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of th ...

, then commandant at Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

, explained in 1762 that, although the boundary between Louisiana and Canada wasn't exact, it was understood the upper Mississippi above the mouth of the Illinois was in Canadian trading territory.

Distinctions became somewhat clearer after the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

in 1763, when Britain acquired Canada and the land claimed by France east of the Mississippi and Spain acquired Louisiana west of the Mississippi. Many French settlers moved west across the river to escape British control. On the west bank, the Spanish also continued to refer to the western region governed from St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

as the ''District of Illinois'' and referred to St. Louis as the ''city of Illinois''.

Exploration and settlement

The first French explorations of the Illinois Country were in the first half of the 17th century, led by explorers and missionaries based in Canada.

The first French explorations of the Illinois Country were in the first half of the 17th century, led by explorers and missionaries based in Canada. Étienne Brûlé

Étienne Brûlé (; – c. June 1633) was the first European explorer to journey beyond the St. Lawrence River into what is now known as Canada. He spent much of his early adult life among the Hurons, and mastered their language and learne ...

explored the upper Illinois country in 1615 but did not document his experiences. Joseph de La Roche Daillon Joseph de La Roche Daillon (died 1656, Paris) was a French Catholic missionary to the Huron Indians and a Franciscan ''Récollet'' priest. He is best remembered in Canada as an explorer and missionary, and in the United States as the discoverer of o ...

reached an oil spring

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

at the northeasternmost fringe of the Mississippi River basin during his 1627 missionary journey.

In 1669–70, Father Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

, a missionary in French Canada, was at a mission station on Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

, when he met native traders from the Illinois Confederation

The Illinois Confederation, also referred to as the Illiniwek or Illini, were made up of 12 to 13 tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley. Eventually member tribes occupied an area reaching from Lake Michicigao (Michigan) to Iowa, Ill ...

. He learned about the great river that ran through their country to the south and west. In 1673–74, with a commission from the Canadian government, Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

territory from Green Bay to the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

, including the Illinois River valley. In 1675, Marquette returned to found a Jesuit mission at the Grand Village of the Illinois

The Grand Village of the Illinois, also called Old Kaskaskia Village, is a site significant for being the best documented historic Native American village in the Illinois River valley. It was a large agricultural and trading village of Native A ...

. Over the next decades missions, trade posts, and forts were established in the region.Native Americans-Historic:The Illinois-Society, The FrenchIllinois State MuseumJacques Marquette 1673 , Virtual Museum of New France

Canadian Museum of History By 1714, the principal European, non-native inhabitants were ''

Canadien

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

'' fur traders

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mo ...

, missionaries and soldiers, dealing with Native Americans, particularly the group known as the Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

. The main French settlements were established at Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

, Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south- ...

, and Sainte Genevieve. By 1752, the population had risen to 2,573.

From the 1710s to the 1730s, the Fox Wars

The Fox Wars were two conflicts between the French and the Fox (Meskwaki or Red Earth People; Renards; Outagamis) Indians that lived in the Great Lakes region (particularly near the Fort of Detroit) from 1712 to 1733.In their book ''The Fox Wars' ...

between the French, French allied tribes and the Meskwaki

The Meskwaki (sometimes spelled Mesquaki), also known by the European exonyms Fox Indians or the Fox, are a Native American people. They have been closely linked to the Sauk people of the same language family. In the Meskwaki language, th ...

(Fox) Native American tribe occurred in what is now northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and Michigan, in particular, over the fur trade. During the conflict, in what is now McLean County, Illinois

McLean County is the largest county by land area in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it had a population of 169,572. Its county seat is Bloomington. McLean County is included in the Bloomington–Normal, IL Metropolit ...

, French and allied forces won a consequential battle against the Meskwaki in 1730.

Fort St. Louis du Rocher

French explorers led by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle built Fort St. Louis on a largebutte

__NOTOC__

In geomorphology, a butte () is an isolated hill with steep, often vertical sides and a small, relatively flat top; buttes are smaller landforms than mesas, plateaus, and tablelands. The word ''butte'' comes from a French word me ...

by the Illinois River in the winter of 1682. Called ''Le Rocher'', the butte provided an advantageous position for the fort above the river. A wooden palisade was the only form of defenses that La Salle used in securing the site. Inside the fort were a few wooden houses and native shelters. The French intended St. Louis to be the first of several forts to defend against English incursions and keep their settlements confined to the East Coast. Accompanying the French to the region were allied members of several native tribes from eastern areas, who integrated with the Kaskaskia: the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

, Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, and Mahican

The Mohican ( or , alternate spelling: Mahican) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, w ...

. The tribes established a new settlement at the base of the butte known as Hotel Plaza.

After La Salle's five-year monopoly ended New France governor Joseph-Antoine de La Barre wished to put Fort Saint Louis along with Fort Frontenac

Fort Frontenac was a French trading post and military fort built in July 1673 at the mouth of the Cataraqui River where the St. Lawrence River leaves Lake Ontario (at what is now the western end of the La Salle Causeway), in a location traditio ...

under his jurisdiction. By orders of the governor, traders and his officer were escorted to Illinois. On August 11, 1683, LaSalle's armorer, Pierre Prudhomme, obtained approximately one and three-quarters of a mile of the north portage shore.

During the earliest of the French and Indian Wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

, the French used the fort as a refuge against attacks by Iroquois, who were allied with the British. The Iroquois forced the settlers, then commanded by Henri de Tonti

Henri de Tonti (''né'' Enrico Tonti; – September 1704), also spelled Henri de Tonty, was an Italian-born French military officer, explorer, and ''voyageur'' who assisted René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, with North American explora ...

, to abandon the fort in 1691. De Tonti reorganized the settlers at Fort Pimitoui in modern-day Peoria.

French troops commanded by Pierre De Liette occupied Fort St. Louis from 1714 to 1718; De Liette's jurisdiction over the region ended when the territory was transferred from Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

to Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. Fur trappers

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most ...

and traders used the fort periodically in the early 18th century until it became too dilapidated. No surface remains of the fort are found at the site today. The region was periodically occupied by a variety of native tribes who were forced westward by the expansion of European settlements. These included the Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

.

On April 20, 1769, an Illinois Confederation warrior assassinated Chief Pontiac

Pontiac or Obwaandi'eyaag (c. 1714/20 – April 20, 1769) was an Odawa war chief known for his role in the war named for him, from 1763 to 1766 leading Native Americans in an armed struggle against the British in the Great Lakes region due ...

while he was on a diplomatic mission in Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south- ...

. According to local legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess ...

, the Ottawa, along with their allies the Potawatomi, attacked a band of Illini along the Illinois River. The tribe climbed to the butte to seek refuge from the attack. The Ottawa and Potawatomi continued the siege until the Illini tribe starved to death. After hearing the story, Europeans referred to the butte as Starved Rock

Starved Rock State Park is a state park in the U.S. state of Illinois, characterized by the many canyons within its . Located just southeast of the village of Utica, in Deer Park Township, LaSalle County, Illinois, along the south bank of the ...

.

Fort de Chartres

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to John Law

John Law may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John Law (artist) (born 1958), American artist

* John Law (comics), comic-book character created by Will Eisner

* John Law (film director), Hong Kong film director

* John Law (musician) (born 1961) ...

and his Company of the West

The Mississippi Company (french: Compagnie du Mississippi; founded 1684, named the Company of the West from 1717, and the Company of the Indies from 1719) was a corporation holding a business monopoly in French colonies in North America and th ...

(which was to become the Company of the Indies in 1719). Hoping to make a fortune mining precious metals in the area, the company with a military contingent sent from New Orleans built a fort to protect its interests. Construction began on the first Fort de Chartres

Fort de Chartres was a French fortification first built in 1720 on the east bank of the Mississippi River in present-day Illinois. It was used as the administrative center for the province, which was part of New France. Due generally to river floo ...

(in present-day Illinois) in 1718 and was completed in 1720.

The original fort was located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, downriver (south) from Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south- ...

and upriver of Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

. The nearby settlement of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois

Prairie du Rocher ("The Rock Prairie" in French) is a village in Randolph County, Illinois, United States. Founded in the French colonial period in the American Midwest, the community is located near bluffs that flank the east side of the Miss ...

, was founded by French-Canadian colonists in 1722, a few miles inland from the fort.

The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the aggressive Fox Indians. The fort was named after Louis, duc de Chartres, son of the regent of France. Because of frequent flooding, another fort was built further inland in 1725. By 1731, the Company of the Indies had gone defunct and turned Louisiana and its government back to the king. The garrison at the fort was removed to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1747, about 18 miles to the south. A new stone fort was planned near the old fort and was described as "nearly complete" in 1754, although construction continued until 1760.

The new stone fort was headquarters for the French Illinois Country for less than 20 years, as it was turned over to the British in 1763 with the

The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the aggressive Fox Indians. The fort was named after Louis, duc de Chartres, son of the regent of France. Because of frequent flooding, another fort was built further inland in 1725. By 1731, the Company of the Indies had gone defunct and turned Louisiana and its government back to the king. The garrison at the fort was removed to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1747, about 18 miles to the south. A new stone fort was planned near the old fort and was described as "nearly complete" in 1754, although construction continued until 1760.

The new stone fort was headquarters for the French Illinois Country for less than 20 years, as it was turned over to the British in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

at the end of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

. The British Crown declared almost all the land between the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

and the Mississippi River from Florida to Newfoundland a Native American territory called the Indian Reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the '' Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

In ...

following the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

. The government ordered settlers to leave or get a special license to remain. This and the desire to live in a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

territory caused many of the ''Canadiens

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

'' to cross the Mississippi to live in St. Louis or Ste. Genevieve. The British soon relaxed its policy and later extended the Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

to the region.

The British took control of Fort de Chartres on October 10, 1765 and renamed it Fort Cavendish

Fort de Chartres was a French fortification first built in 1720 on the east bank of the Mississippi River in present-day Illinois. It was used as the administrative center for the province, which was part of New France. Due generally to river floo ...

. The British softened the initial expulsion order and offered the Canadien inhabitants the same rights and privileges enjoyed under French rule. In September 1768, the British established a Court of Justice, the first court of common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

in the Mississippi Valley (the French law system is called civil law).

After severe flooding in 1772, the British saw little value in maintaining the fort and abandoned it. They moved the military garrison to the fort at Kaskaskia and renamed it Fort Gage. Chartres' ruined but intact magazine is considered the oldest surviving European structure in Illinois and was reconstructed in the 20th century, with much of the rest of the Fort.

Agricultural settlement and slavery

According to historian, Carl J. Ekberg, the French settlement pattern in Illinois Country was generally unique in 17th- and 18th-century French North America. These were unlike other such French settlements, which primarily had been organized in separated homesteads along a river with long rectangular plots stretching back from the river (ribbon plots). The Illinois Country French, although they marked long-ribbon plots, did not reside on them. Instead, settlers resided together in farming villages, more like the farming villages of northern France, and practiced communal agriculture.Ekberg (2000), p. 28-32 After the port of , along the Mississippi River to the south, was founded in 1718, more African slaves were imported to the Illinois Country for use as agricultural and mining laborers. By the mid-eighteenth century, slaves accounted for as much as a third of the population.Ekberg (2000), p. 2-3Other settlements

*In 1675,Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

founded the mission of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin at the Grand Village of the Illinois

The Grand Village of the Illinois, also called Old Kaskaskia Village, is a site significant for being the best documented historic Native American village in the Illinois River valley. It was a large agricultural and trading village of Native A ...

, near present Utica, Illinois, which was destroyed by Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

in 1680.

* Peoria was at first the southernmost part of

* Peoria was at first the southernmost part of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

, then the northernmost part of the French Colony of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and finally the westernmost part of the newly formed United States. Fort Crevecoeur

Fort Crevecoeur (French: ''Fort Crèvecœur'') was the first public building erected by Europeans within the boundaries of the modern state of Illinois and the first fort built in the West by the French. It was founded on the east bank of the ...

was first founded in 1680. Another fort, often called Fort Pimiteoui, and later Old Fort Peoria, was established in 1691. French interests dominated at Peoria for well over a hundred years, from the time the first French explorers came up the Illinois River in 1673 until the first United States settlers began to move into the area around 1815. A small French presence persisted for a time on the east bank of the river, but was gone by about 1846. Today, only faint echoes of French Peoria survive in the street plan of downtown Peoria, and in the name of an occasional street, school, or hotel meeting room: ''Joliet'', ''Marquette'', ''LaSalle''.

*The Mission of the Guardian Angel

The Mission of the Guardian Angel () was a 17th-century Jesuit mission in the vicinity of what is now Chicago, Illinois. It was established in 1696 by Father François Pinet, a French Jesuit priest. The mission was abandoned by 1700; its exact lo ...

was established near the Chicago portage

The Chicago Portage was an ancient portage that connected the Great Lakes waterway system with the Mississippi River system. Connecting these two great water trails meant comparatively easy access from the mouth of the St Lawrence River on the At ...

between 1696-1700.

*

*Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south- ...

, established in 1696 by French missionaries from Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, was one of the earliest permanent settlements in the region. It became one of the most populous of the northern towns. In 1787, it was made the seat of St. Clair County in the Northwest Territory. In 1801, William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, then governor of Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a congressional act that President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, ...

, enlarged St. Clair County to administer a vast area extending to the Canada–US border. By 1814, the county had been reduced to almost the size of the present St. Clair County, Illinois. The county seat was shifted from Cahokia to Belleville. On April 20, 1769, the great Indian leader Chief Pontiac

Pontiac or Obwaandi'eyaag (c. 1714/20 – April 20, 1769) was an Odawa war chief known for his role in the war named for him, from 1763 to 1766 leading Native Americans in an armed struggle against the British in the Great Lakes region due ...

was murdered in Cahokia by a chief of the Peoria.

*Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

, established in 1703, was at first small mission station for the French. It flourished to become capital of the Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. Its ...

, 1809–1818, and the first capital of the state of Illinois, 1818-1820. The French built a fort here in 1721, which was destroyed in 1763 by the British. (The fort was situated above what was then the lower course of the Kaskaskia River

The Kaskaskia River is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 13, 2011 in central and southern Illinois in the Un ...

, but became the new channel of the Mississippi in 1881.) During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, General George Rogers Clark took possession of the village in 1778. The residents rang the church bell in celebration, and it became known as the "liberty bell". (It had been sent in 1741 by King Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

.) Flooding and a lateral shift of the river channel in 1881 cut off the old settlement from the mainland of Illinois and destroyed some of the village and its archaeology. Much of the village cemetery was transferred to the higher ground of Fort Kaskaskia State Park

Fort Kaskaskia State Historic Site is a 200-acre (0.8 km²) park near Chester, Illinois, on a blufftop overlooking the Mississippi River. It commemorates the vanished frontier town of ''Kaskaskia, Illinois, Old Kaskaskia'' and the support ...

across the river. Today visitors can reach the remnants of Kaskaskia only by a bridge and road from the Missouri side. In the Great Flood of 1993

The Great Flood of 1993 (or Great Mississippi and Missouri Rivers Flood of 1993) was a flood that occurred in the Midwestern United States, along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and their tributaries, from April to October 1993. The flood wa ...

, the Mississippi submerged all but a few rooftops and the steeple of the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Church of the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.

It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth w ...

, built in 1843 and moved brick by brick to the new location on Kaskaskia Island about 1893.

*In 1720, Philip Francois Renault

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, the Director of Mining Operations for the Company of the West, arrived with about 200 laborers and mechanics and 500 African slaves from Saint-Domingue to work the mines. However, the mines yielded only unprofitable coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

and lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, providing insufficient revenues for the Company of the West to survive. In 1723, Renault, with his workers and slaves, established the village St. Philippe (on the Bottoms down from the present-day unincorporated community of Renault, Illinois in Monroe County, Illinois

Monroe County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it had a population of 34,962. Its county seat and largest city is Waterloo.

Monroe County is included in the St. Louis, MO-IL Metropolitan Stati ...

.) It was about 3 miles north of Fort de Chartres. This is the first record of African slaves in the region. Some of the French farmers also used slaves for labor, but most families held only a few, if any. The village quickly produced an agricultural surplus, with its goods sold to lower Louisiana, as well as to settlements less successful than those in the Illinois Country, such as Arkansas Post.

*The original Ste. Genevieve was established around 1750 along the western banks of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. The village consisted of mostly farmers and merchants of French-Canadian descent from the settlements on the east side. Despite flooding, the town remained in that location until the great flood of 1785 destroyed much property. The villagers decided to move the entire village to higher ground about two miles north and half a mile back from the river floodplain. The city has retained the most buildings of French Colonial

French colonial architecture includes several styles of architecture used by the French during colonization. Many former French colonies, especially those in Southeast Asia, have previously been reluctant to promote their colonial architectur ...

architecture in the US.

*The French established Fort Orleans in 1723 along the Missouri River near Brunswick, Missouri.

* Fort Vincennes, on the Wabash River, later known as ''St. Vincennes'' and eventually Vincennes, Indiana

Vincennes is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Indiana, United States. It is located on the lower Wabash River in the southwestern part of the state, nearly halfway between Evansville and Terre Haute. Founded in 1732 by French fur ...

, was established in 1732. The British renamed it Fort Sackville

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the French, British and U.S. forces built and occupied a number of forts at Vincennes, Indiana. These outposts commanded a strategic position on the Wabash River. The names of the installations were change ...

after their capture of it in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

(also known as the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

.) George Rogers Clark renamed it Fort Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first a ...

, for the Governor of Virginia, when he took it in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. Although part of the original expansive Illinois Country, as part of the Northwest Territory, it became the seat of a separate county.

*The French built Fort de L'Ascension (later, de Massiac) on the Ohio River in 1757 near the present Metropolis, Illinois

Metropolis is a city located along the Ohio River in Massac County, Illinois, Massac County, Illinois, United States. It has a population of 6,537 according to 2010 United States Census, the 2010 United States Census. Metropolis is the county sea ...

.

*St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

was founded in 1764 by French fur traders. In 1765, it was made the capital of Upper Louisiana; and after 1767, control of the region west of the Mississippi was given to the Spanish ("District of Illinois"). In 1780, St. Louis was attacked by British forces, mostly Native Americans, during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

British province of Quebec

Following the British occupation of the east bank of the Mississippi in 1765, someCanadien

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

settlers remained in the area, while others crossed the river, forming new settlements such as St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. The British faced an uprising of Native Americans known as Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

. Longtime allies of the French, the Kaskaskia and Peoria tribes had resisted the British, and Pontiac Pontiac may refer to:

*Pontiac (automobile), a car brand

*Pontiac (Ottawa leader) ( – 1769), a Native American war chief

Places and jurisdictions Canada

*Pontiac, Quebec, a municipality

** Apostolic Vicariate of Pontiac, now the Roman Catholic D ...

led a coalition of the Illini, and Kickapoo, Miami, Ojibway, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Seneca, Wea, and Wyandot against the British. Pursuant to the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the S ...

Captain Thomas Sterling and the 42nd Regiment of Foot

The 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot was a Scottish infantry regiment in the British Army also known as the Black Watch. Originally titled Crawford's Highlanders or the Highland Regiment and numbered 43rd in the line, in 1748, on the disban ...

took command of Fort de Chartres

Fort de Chartres was a French fortification first built in 1720 on the east bank of the Mississippi River in present-day Illinois. It was used as the administrative center for the province, which was part of New France. Due generally to river floo ...

, from the French commandant, Captain Louis St. Ange de Bellerive in 1765.

Illinois Country under American control

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. In November 1778, the Virginia legislature created the county of Illinois, comprising all of the lands lying west of the Ohio River to which Virginia had any claim, with Kaskaskia as the county seat. Captain John Todd was named as governor. However, this government was limited to the former Canadien

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

settlements and was rather ineffective.

For their assistance to General Clark in the war, settled Canadien and Indian residents of Illinois Country were given full citizenship. Under the Northwest Ordinance and many subsequent treaties and acts of Congress, the Canadien and Indian residents of Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

and Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in ...

were granted specific exemptions, as they had declared themselves citizens of Virginia. The term ''Illinois Country'' was sometimes used in legislation to refer to these settlements.

Much of the Illinois Country region became an organized territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sover ...

of the United States with the establishment of the Northwest Territory in 1787. In 1803, the old Illinois Country area west of the Mississippi was gained by the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

.

See also

*Illinois Country French

Missouri French (french: français du Missouri) or Illinois Country French (french: français du Pays des Illinois) also known as , and nicknamed "Asimina, Paw-Paw French" often by individuals outside the community but not exclusively, is a vari ...

, a dialect of French spoken in Missouri

* Ohio Country

* French Colonial Historic District

The French Colonial Historic District is a historic district that encompasses a major region of 18th-century French colonization of the Americas, French colonization in southwestern Illinois. The district is anchored by Fort de Chartres and Fort ...

* List of commandants of the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country was governed by military commandants for its entire period under French and British rule, and during its time as a county of Virginia. The presence of French military interests in the Illinois Country began in 1682 when Rob ...

* Slavery in New France

Slavery in New France was practiced by some of the indigenous populations, which enslaved outsiders as captives in warfare, but it was European colonization that made commercial chattel slavery become common in New France. By 1750, two-thirds o ...

Notes

Bibliography

*Alvord, Clarence Walworth. ''The Illinois Country'', 1673–1818'' (1920online

*Belting, Natalia Maree, ''Kaskaskia under the French Regime'' (1948

online

*Brackenridge, Henri Marie, ''Recollections of Persons and Places in the West'' (Google Books) *Ekberg, Carl J., ''Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country'', Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007. *Ekberg, Carl J., ''Francois Vallé and His World: Upper Louisiana Before Lewis and Clark'', Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2002. *Ekberg, Carl J., ''French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times'', Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000, *Ekberg, Carl J., ''Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier'', Tucson, AZ: Patrice Press, 1996, * Lippincott, Isaac. "Industry among the French in the Illinois country." ''Journal of Political Economy'' 18.2 (1910): 114-128

online

External links

Library of Congress exhibit

Louisiana Digital Libraries

Plan for Fort Orleans {{Authority control 1699 establishments in New France 1765 disestablishments in New France Former French colonies Louisiana (New France) Pre-statehood history of Illinois Pre-statehood history of Indiana Pre-statehood history of Kentucky Pre-statehood history of Ohio Pre-statehood history of Missouri Former territorial entities in North America