Paris–Madrid race on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

:''See also the  At the time in France there was a great interest in international car races. In 1894 the Paris–Rouen was the first car race in the world, followed by races from Paris to

At the time in France there was a great interest in international car races. In 1894 the Paris–Rouen was the first car race in the world, followed by races from Paris to

The starting point was in front of the ''Eau des Suisses'' (''Swiss Lake'' :fr: Pièce d'eau des Suisses) at the

The starting point was in front of the ''Eau des Suisses'' (''Swiss Lake'' :fr: Pièce d'eau des Suisses) at the

Further south, another car left the road and went into a group of spectators. Two people were said to be killed in the crowd.

E.T. Stead, (Phil Stead) in the massive De Dietrich, lost control while overtaking another car in Saint-Pierre-du-Palais, and was injured. He was rescued and tended to by the only lady competitor

Further south, another car left the road and went into a group of spectators. Two people were said to be killed in the crowd.

E.T. Stead, (Phil Stead) in the massive De Dietrich, lost control while overtaking another car in Saint-Pierre-du-Palais, and was injured. He was rescued and tended to by the only lady competitor

Grand Prix History online

(retrieved 11 June 2017); ) Newspapers and experts declared the "death of sport racing". It was commonly thought that no other races would be allowed, and for many years this was true: there would not be another race on public highways until the 1927 ''

Donatella Biffignandi: "Parigi-Madrid 1903. Una corsa che non ebbe arrivo", Auto d'Epoca gennaio 2003

{{DEFAULTSORT:Paris-Madrid race Auto races 1903 in motorsport Motorsport in Europe Motorsport in France Motorsport in Spain May 1903 sports events

1911 Paris to Madrid air race

The 1911 Paris to Madrid air race was a three-stage international flying competition, the first of several European air races of that summer. The winner was French aviator Jules Védrines, although his win, along with the rest of the race, were ...

.''

The Paris–Madrid race of May 1903 was an early experiment in auto racing, organized by the Automobile Club de France

The Automobile Club of France (french: Automobile Club de France, links=no) (ACF) is a men's club founded on November 12, 1895 by Albert de Dion, Paul Meyan, and its first president, the Dutch-born Baron Etienne van Zuylen van Nijevelt.

The Auto ...

(ACF) and the Spanish Automobile Club, Automóvil Club Español.

At the time in France there was a great interest in international car races. In 1894 the Paris–Rouen was the first car race in the world, followed by races from Paris to

At the time in France there was a great interest in international car races. In 1894 the Paris–Rouen was the first car race in the world, followed by races from Paris to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

, Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to N ...

, Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.

The organisation

Problems in getting authorizations

The French government was against the idea of races being held on public streets. After the Paris–Berlin race of 1901, the Minister of Internal Affairs M.Waldeck-Rousseau

Pierre Marie René Ernest Waldeck-Rousseau (; 2 December 184610 August 1904) was a French Republican politician who served as the Prime Minister of France.

Early life

Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau was born in Nantes, Brittany. His father, René Wa ...

stated that no other races would be authorized.

The Paris–Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

was strongly supported by King Alphonse XIII of Spain, and French media suggested that France could not withdraw from the competition, being the country with the most advanced technology in car manufacturing.

Baron de Zuylen, president of the ACF, managed to overcome the opposition of Prime Minister Émile Combes

Émile Justin Louis Combes (; 6 September 183525 May 1921) was a French statesman and freemason who led the Bloc des gauches's cabinet from June 1902 to January 1905.

Career

Émile Combes was born in Roquecourbe, Tarn. He studied for the pri ...

by stating that the roads were indeed public, the public wanted the races, and many local administrators were eager to have a race pass through their towns.

Many French car manufacturers supported the request, employing of over 25 thousand workers and producing 16 million Francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

per year of export alone. Since races were necessary to promote the brand

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create an ...

s, they interceded with the government who finally agreed with the race. The Council of Ministries and the President gave their support to the race on February 17, 1903, while the ACF had been accepting applications since January 15.

The setup

In just 40 days over 300 drivers enrolled, many more than expected. The net worth of the cars involved in the race surpassed 7 million Francs. The race was to span over 1307 kilometers, in three legs:Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

– Bordeaux (552 km), Bordeaux – Vitoria (km 335) and Vitoria – Madrid (420 km). The rules were published in the three biggest motor sport magazines of France: France Automobile

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, La Locomotion

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

, La Vie Automobile

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

.

The rules called for four weight categories: less than 250 kg, 250 to 400 kg, 400 to 650 kg and 650 to 1000 kg. The weight was intended as dry weight

Vehicle weight is a measurement of wheeled motor vehicles; either an actual measured weight of the vehicle under defined conditions or a gross weight rating for its weight carrying capacity.

Curb or kerb weight

Curb weight (U.S. English) or kerb ...

, excluding the driver, fuel, batteries, oil, spare parts, tools, food and water, driver's luggage, headlights and lights harnesses, horns and eventual external starter.

The subscription cost ranged from 50 to 400 Francs, depending on weight. The two heaviest classes were supposed to have a driver and a mechanic (weighing no less than 60 kg, the same for the whole race), while the two lighter ones required only a driver.

The starting order was drawn at random between the cars enrolled in the first thirty days, and in progression for the drivers enrolled after February 15. The race start was established for the 3.30 AM of Sunday May 24, from Versailles Gardens, les Jardins de Versailles. As in many races before, the cars were to leave one by one, with a two-minute delay.

The "Absolutely Closed Parks" rule was introduced: at the end each race leg, the cars were to be taken by a commissioner to closed pens, where no repairs or maintenance were allowed. Any refueling or repairs had to be done during the race time. While in transit to the pens, the cars had to cross the towns in parade, accompanied by a race officer on a bicycle who was supposed to record the exact time of the crossing, which was later deducted from the overall driver's time. The time records were written on time slips and kept in sealed metal boxes on every car.

While Versailles – Bordeaux was a mainstay of road races (the Gordon Bennett Cup has been kept there in 1901), the Bordeaux – Vitoria leg presented more uncertainty: it was full of sharp turns, climbs, narrow bridges, rail crossings, stone roads and long, paved stretches where high speeds would be possible.

The participants

315 racers enrolled, but only 224 were present on the start line, subdivided as follows: * 88 cars in the heaviest class (650 to 1000 kg) * 49 cars between 400 and 650 kg * 33 ''voiturettes'' under 400 kg * 54 motorcycles Many famous racers and brands joined the race.René de Knyff

Chevalier René de Knyff (December 10, 1865 in Antwerp, Belgium – 1954 in France) was a French pioneer of car racing and later a president of ''Commission Sportive Internationale'' (''CSI''), now known as FIA.

Between 1897 and 1903 he took ...

, Henri

Henri is an Estonian, Finnish, French, German and Luxembourgish form of the masculine given name Henry.

People with this given name

; French noblemen

:'' See the ' List of rulers named Henry' for Kings of France named Henri.''

* Henri I de Mon ...

and Maurice Farman

Maurice Alain Farman (21 March 1877 – 25 February 1964) was a British-French Grand Prix motor racing champion, an aviator, and an aircraft manufacturer and designer.

Biography

Born in Paris to English parents, he and his brothers Richard and ...

, Pierre de Crawhez

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

, Charles S. Rolls were racing with Panhard-Levassor

Panhard was a French motor vehicle manufacturer that began as one of the first makers of automobiles. It was a manufacturer of light tactical and military vehicles. Its final incarnation, now owned by Renault Trucks Defense, was formed ...

, mighty 4-cylinders cars capable of 70 hp and 130 km/h

Henri Fournier, William K. Vanderbilt

William Kissam "Willie" Vanderbilt I (December 12, 1849 – July 22, 1920) was an American heir, businessman, philanthropist and horsebreeder. Born into the Vanderbilt family, he managed his family's railroad investments.

Early life

William Kiss ...

, Fernand Gabriel

Fernand is a masculine given name of French origin. The feminine form is Fernande.

Fernand may refer to:

People Given name

* Fernand Augereau (1882–1958), French cyclist

* Fernand Auwera (1929–2015), Belgian writer

* Fernand Baldet (1885 ...

and Baron de Forest enrolled for the Mors brand, who presented a daring new wind-splitting radiator on the classic ''bateau'' frames. The car was very powerful, with 90 hp and a maximum speed of almost 140 km/h

Mercedes deployed 11 cars, ranging from 60 to 90 hp. De Dietrich

The history of the de Dietrich family has been linked to that of France and of Europe for over three centuries.

To this day, the company that bears the family name continues to play a major role in the economic life of Alsace.

De Dietrich is a h ...

and many other French brands such as Gobron Billiè, Napier and Charron Girardot shunned the lightest classes and raced only with their most powerful and heavy models. The smallest cars from those brands were still present in the hands of amateurs and private racers. Other French brands included Darracq

A Darracq and Company Limited owned a French manufacturer of motor vehicles and aero engines in Suresnes, near Paris. The French enterprise, known at first as A. Darracq et Cie, was founded in 1896 by Alexandre Darracq after he sold his Gladi ...

, De Dion-Bouton

De Dion-Bouton was a French automobile manufacturer and railcar manufacturer operating from 1883 to 1953. The company was founded by the Marquis Jules-Albert de Dion, Georges Bouton, and Bouton's brother-in-law Charles Trépardoux.

Steam cars

T ...

, Clément-Bayard

Clément-Bayard, Bayard-Clément, was a French manufacturer of automobiles, aeroplanes and airships founded in 1903 by entrepreneur Gustave Adolphe Clément. Clément obtained consent from the Conseil d'Etat to change his name to that of his b ...

, Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

, and Décauville.

Renault

Groupe Renault ( , , , also known as the Renault Group in English; legally Renault S.A.) is a French multinational automobile manufacturer established in 1899. The company produces a range of cars and vans, and in the past has manufactured ...

joined the race with two cars driven by Marcel Renault

Marcel Renault (14 May 1872 – 26 May 1903) was a French racing driver and industrialist, co-founder of the carmaker Renault. He was the brother of Louis and Fernand Renault.

Renault was born in Paris; he and his brothers jointly founded th ...

and Louis Renault, two founders of the brand and experienced drivers.

Italian manufacturer Fiat

Fiat Automobiles S.p.A. (, , ; originally FIAT, it, Fabbrica Italiana Automobili di Torino, lit=Italian Automobiles Factory of Turin) is an Italian automobile manufacturer, formerly part of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, and since 2021 a subsidiar ...

presented only two cars, but could count on two of the best drivers of the time, Vincenzo Lancia

Vincenzo Lancia (24 August 1881 – 15 February 1937) was an Italian racing driver, engineer and founder of Lancia.

Vincenzo Lancia was born in the small village of Fobello on 24 August 1881, close to Turin; his family tree starts in Fabell ...

and Luigi Storero Luigi Storero (18 October 1868 – 1956) was an Italian racecar driver and engineer from Torino.

He joined his father, Giacomo Storero's company (established 1850), which in 1884 started making bicycles. Luigi Storero was a winner of bicycle race ...

.

The public

French newspapers were excited and covered the race with great enthusiasm. The race was presented as the biggest race since the invention of the car, and over 100,000 people managed to reach Versailles at 2 am for the race start. The first hundred of kilometers of the race track were crowded with spectators, and rail stations were swarmed with people trying to reach Versailles. The crowd and the darkness convinced the organisers to delay the race start by half an hour, and to reduce the delay between cars to just one minute. The day was expected to be very hot, and the officials wanted to avoid the heat of the late morning.The race

Start line and first checkpoint

The starting point was in front of the ''Eau des Suisses'' (''Swiss Lake'' :fr: Pièce d'eau des Suisses) at the

The starting point was in front of the ''Eau des Suisses'' (''Swiss Lake'' :fr: Pièce d'eau des Suisses) at the gardens of Versailles

The Gardens of Versailles (french: Jardins du château de Versailles ) occupy part of what was once the ''Domaine royal de Versailles'', the royal demesne of the château of Versailles. Situated to the west of the palace, the gardens cover so ...

. In the early morning of May 24, 1903, participants started at one minute intervals for the first leg to Bordeaux via Saint Cyr, Trappes

Trappes () is a Communes of France, commune in the Yvelines departments of France, department, region of Île-de-France, north-central France. It is a banlieue located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the Kilometre Zero, center of Paris, i ...

, Coignières

Coignières () is a French commune in the Yvelines department, region of Île-de-France.

Geography

Coignières is situated southwest of Versailles. Its neighbours include Maurepas to the north, Mesnil-Saint-Denis and Lévis-Saint-Nom to the ...

, Le Perray, Rambouillet

Rambouillet (, , ) is a subprefecture of the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region of France. It is located beyond the outskirts of Paris, southwest of its centre. In 2018, the commune had a population of 26,933.

Rambouillet lie ...

, Chartres

Chartres () is the prefecture of the Eure-et-Loir department in the Centre-Val de Loire region in France. It is located about southwest of Paris. At the 2019 census, there were 170,763 inhabitants in the metropolitan area of Chartres (as def ...

, Clayes, Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the prefecture of the department of Indre-et-Loire. The commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabitants as of 2018 while the population of the whole metro ...

, Ruffec, Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; oc, Engoleime) is a commune, the prefecture of the Charente department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern France.

The inhabitants of the commune are known as ''Angoumoisins ...

, Chevanceaux, Guitres, Libourne

Libourne (; oc, label= Gascon, Liborna ) is a commune in the Gironde department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

It is the wine-making capital of northern Gironde and lies near Saint-Ém ...

. The first car was expected to arrive at Bordeaux around noon.

The soldiers deployed to manage the crowd proved insufficient, and people swarmed the streets. The first racer to leave, Charles Jarrott with his mechanic Bianchi in a 1000 kg, 45 hp De Dietrich, tried to slow down to 40 miles per hour, to give people time to evacuate the road in front of the car, but it only worsened the problem since people just waited longer to move away.

De Knyff on his Panhard-Levassor

Panhard was a French motor vehicle manufacturer that began as one of the first makers of automobiles. It was a manufacturer of light tactical and military vehicles. Its final incarnation, now owned by Renault Trucks Defense, was formed ...

left second, followed by Louis Renault in a 650 kg, 30 cv Renault. Théry in Décauville (640 kg, 24 cv), another De Diétrich, a Mors, a Panhard and a light Passy Thellier, (400 kg, 16 cv) were the next. The start took until 6.45 a.m, almost three hours.

The race proved to be very difficult for the drivers: the dangers from the crowd added to the thick dust cloud raised by the cars. The weather had been dry for the prior two weeks, and dust covered the roads. Officials watered down just the first kilometer of road, and the short delay between cars worsened the problem. Visibility dropped to few meters, and people stood in the middle of the road to see the cars, becoming a persistent danger for the drivers.

After the first control point in Rambouillet

Rambouillet (, , ) is a subprefecture of the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region of France. It is located beyond the outskirts of Paris, southwest of its centre. In 2018, the commune had a population of 26,933.

Rambouillet lie ...

, and the second in Chartres

Chartres () is the prefecture of the Eure-et-Loir department in the Centre-Val de Loire region in France. It is located about southwest of Paris. At the 2019 census, there were 170,763 inhabitants in the metropolitan area of Chartres (as def ...

the crowd became less dense. Just after Rambouillet, Louis Renault's wild racing style allowed him to overcome both De Knyff and Jarrott, who were struggling for first place but keeping a more prudent stance to avoid the crowd. Thery and Stead followed at distance, while Jenatzy's Mercedes and Gabriel's Mors were leading an incredible recovery, surpassing 25 cars and achieving a spot in the first ten drivers.

Another incredible feat was achieved by Marcel Renault

Marcel Renault (14 May 1872 – 26 May 1903) was a French racing driver and industrialist, co-founder of the carmaker Renault. He was the brother of Louis and Fernand Renault.

Renault was born in Paris; he and his brothers jointly founded th ...

, who started in the 60th position but managed to almost reach the race leaders at the control point of Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglome ...

.

Outside of the leading positions, the accidents continued throughout the day; cars hit trees and disintegrated, they overturned and caught fire, axles broke and inexperienced drivers crashed on the rough roads.

The finishing line

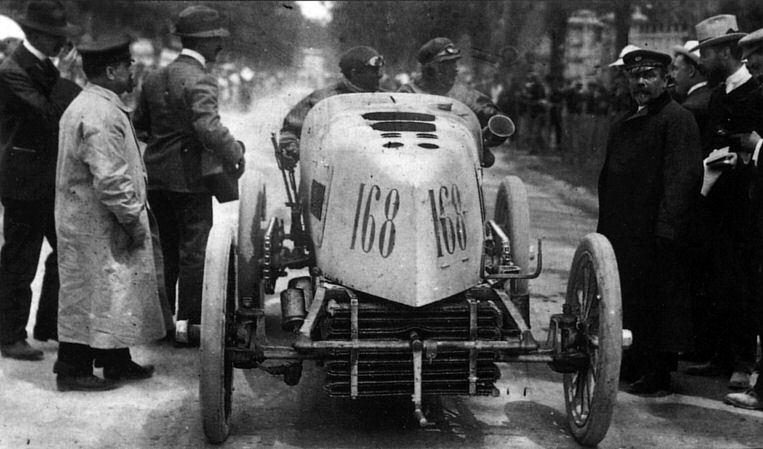

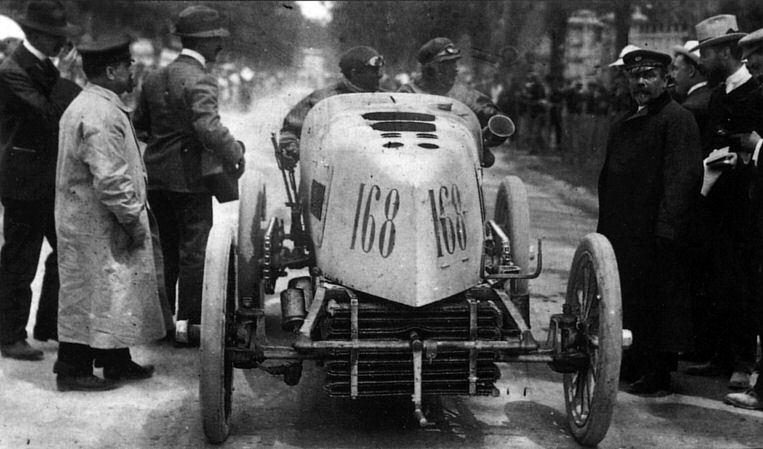

Louis Renault reached Bordeaux in first place at noon, while Jarrott, who was racing with a defective clutch and was troubled by mechanical problems to the engine and exhaust, arrived half an hour later followed by Gabriel, Salleron, Baras, de Crawhez, Warden, Rougier, Jenatzy and Voigt. All the drivers were physically exhausted: the cars were heavy, and required a great deal of force to maneuver. Dust made their eyes sore, and many of them had issues with the engines and burned their hands while fixing them. Gabriel, who left as 168th and arrived third, was later recognized as the winner when the time slips were tallied up. A few big names had to withdraw, and news slowly started coming to the finishing line. Vanderbilt broke a cylinder on his Mors, and had to leave the race. Baron de Caters's Mercedes hit a tree, but was unhurt and probably was fixing the car to keep racing. Lady race car driverCamille du Gast

Camille du Gast (Marie Marthe Camille Desinge du Gast, Camille Crespin du Gast, 30 May 1868 – 24 April 1942) was one of a trio of pioneering French female motoring celebrities of the ''Belle Epoque'', together with Hélène de Rothschild (Baro ...

(Crespin) was placed as high as 8th in her 30 hp De Dietrich

The history of the de Dietrich family has been linked to that of France and of Europe for over three centuries.

To this day, the company that bears the family name continues to play a major role in the economic life of Alsace.

De Dietrich is a h ...

until she stopped to help fellow driver E. T. Stead (Phil Stead) who had crashed. She finished 45th. Charles Jarrott

Charles Jarrott (16 June 1927 – 4 March 2011) was a British film and television director. He was best known for costume dramas he directed for producer Hal B. Wallis, among them '' Anne of the Thousand Days'', which earned him a Golden Glob ...

, who finished fourth overall with his de Dietrich, asserted that Stead would have died if she had not stopped.

Rumours of accidents

News of an accident atAblis

Ablis () is a commune in the Yvelines department in north-central France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and ter ...

arrived: a woman was hit by a car and injured. This later was found to be false.

Someone started talking about an accident involving Marcel Renault

Marcel Renault (14 May 1872 – 26 May 1903) was a French racing driver and industrialist, co-founder of the carmaker Renault. He was the brother of Louis and Fernand Renault.

Renault was born in Paris; he and his brothers jointly founded th ...

; with his incredibly fast pace he should have already arrived by that time, but was still missing. News arrived stating that he had an accident at Couhé Vérac. He would die 48 hours later, never regaining consciousness.

There is a memorial at the place where his accident occurred on the RN 10 road in the Poitou-Charentes

Poitou-Charentes (; oc, Peitau-Charantas; Poitevin-Saintongese: ) is a former administrative region on the southwest coast of France. It is part of the new region Nouvelle-Aquitaine. It comprises four departments: Charente, Charente-Maritime, D ...

region of France. This monument was destroyed by the Germans during World War II.

Porter's Wolseley was destroyed at a rail crossing where the bar was unexpectedly down. The car hit it and overturned, killing his mechanic. Georges Richard hit a tree in Angoulême, trying to avoid a farmer standing in the middle of the road, and news came that in Châtellerault

Châtellerault (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Châteulrô/Chateleràud''; oc, Chastelairaud) is a commune in the Vienne department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region in France. It is located in the northeast of the former province Poitou, and the ...

Tourand's Brunhot had hit spectators while avoiding a child who crossed the road. A soldier named Dupuy intervened and saved the child, but was killed and the car lost control, killing a spectator.

Further south, another car left the road and went into a group of spectators. Two people were said to be killed in the crowd.

E.T. Stead, (Phil Stead) in the massive De Dietrich, lost control while overtaking another car in Saint-Pierre-du-Palais, and was injured. He was rescued and tended to by the only lady competitor

Further south, another car left the road and went into a group of spectators. Two people were said to be killed in the crowd.

E.T. Stead, (Phil Stead) in the massive De Dietrich, lost control while overtaking another car in Saint-Pierre-du-Palais, and was injured. He was rescued and tended to by the only lady competitor Camille du Gast

Camille du Gast (Marie Marthe Camille Desinge du Gast, Camille Crespin du Gast, 30 May 1868 – 24 April 1942) was one of a trio of pioneering French female motoring celebrities of the ''Belle Epoque'', together with Hélène de Rothschild (Baro ...

. The third De Dietrich driven by Loraine Barrow crashed into a tree and was said to have blown up, wounding the driver and killing the mechanic. Barrow had been in bad health before the race, but had to leave nevertheless since the rules forbade a driver change.

Rolls's Panhard-Levassor, Mayhew's Napier, Maurice Farman's Panhard, the Wolseleys of Herbert Austin and Sidney Girling, Béconnais's Darracq all had major technical issues, and had to retire.

Overall, half the cars had crashed or retired, and at least twelve people were presumed dead, and over 100 wounded. The actual count was lower, with eight people dead, three spectators and five racers.

The aftermath

The race is cancelled

The French Parliament reacted strongly to the news of the numerous accidents. An emergency Council of Ministers was called, and the officers were forced to shut down the race in Bordeaux, transfer the cars to Spanish territory and restart from the border to Madrid. The Spanish government denied permission for this, and the race was declared officially over in Bordeaux. The race was called off, and by order of the French Government the cars were impounded and towed to the rail station by horses and transported to Paris by train. (The cars' engines were not even allowed to be restarted.(retrieved 11 June 2017); ) Newspapers and experts declared the "death of sport racing". It was commonly thought that no other races would be allowed, and for many years this was true: there would not be another race on public highways until the 1927 ''

Mille Miglia

The Mille Miglia (, ''Thousand Miles'') was an open-road, motorsport endurance race established in 1927 by the young Counts Francesco Mazzotti and Aymo Maggi, which took place in Italy twenty-four times from 1927 to 1957 (thirteen before World ...

''.

The effects of the race extended to automobile regulations. Motions to outlaw speeding by car at over were proposed, some calling for the ban to be enforced in races, too.

Public opinion is mixed

While some newspapers, such as ''Le Temps'', used the disaster in a demagogic way to attack the car fashion and the race world, other (such as ''la Presse'') tried to downplay the issue, stating that just 3 "involuntary" victims, the spectators, had been sacrificed on the "altar of Progress". ''La Liberté'' rejected the call for a ban on sport races, since automobile manufacturing was a source of French pride, and the socialist ''Petite Republique'' defended the car as a mean of mass empowerment and freedom from work fatigue. ''Le Matin'' supported the opinion first stated by the Marquis de Dion, that speed races were useless, both as a publicity stunt and as testbed for technological improvement. The only useful races were the endurance and fuel efficiency ones. There was a bit of truth in the opinion that race cars had very little in common with common commercial cars, with their oversized engines and extreme solutions. A specialized magazine, ''L'Auto'', tried to reach consensus on a new set of rules for sport races; fewer drivers and cars, classes based on speed and power (not just weight), and the public placed far away from the race course.Inquiry on the causes

The first fair and authoritative analysis came from ''La Locomotion Automobile'', which identified the causes of the disaster. The massacre was due to a few concurrent factors: * Speed. Cars raced at over 140 km/h, a speed not reached even by the fastest trains of the time. * Dust, which worsened the driving conditions and was direct cause of a few accidents. * Excessive and poorly managed public, worsened by an inadequate crowd control and a general underestimation of the danger involved in a car race. The police force was accused of being more interested in the race than the public safety, forgetting to intervene when people crossed the road or stood in it. The organization was held responsible for poor choices. The random start order was a mess, since faster and more powerful cars were mixed with slower and smaller ones, causing many unneeded overtakings. Some drivers (such as Mouter in the De Dietrich) managed to advance almost 80 places, just because they started far back and had many small cars and amateur drivers ahead. The interval between starts was reduced to one minute only, worsening the dust problem and randomly mixing in motorcycles, ''voiturette

A voiturette is a miniature automobile.

History

''Voiturette'' was first registered by Léon Bollée in 1895 to name his new motor tricycle. The term became so popular in the early years of the motor industry that it was used by many makers t ...

s'' and race cars.

The rule preventing a driver change before the race start was also under scrutiny. Some drivers, it was said including Marcel Renault, had health problems at the start line but had to race because the brands could not retire a vehicle, and no driver change was possible.

Causes of accidents

The London's weekly magazine ''The Car'' verified the death claims, discovering that some of them were only rumours, and investigated the actual causes. In the Angoulême accident killing the soldier and a spectator, it was discovered that the child was at fault, having crossed the road after escaping his parents. The accident at the rail cross that occurred to Porter was a fault of the organization, since the cross was not attended. The leading hypothesis about a loss of control due to a mechanical failure was dismissed. Barrow's car did not blow up, it hit a dog while avoiding another one and crashed into a tree, but did not explode or burn. The idea of an engine exploding had great appeal to the public, but was a product of ignorance and hype. Marcel Renault's and Stead's accidents were the only true racing incidents, and were both due to the excessive dust impairing visibility during an overtaking. The blame was put on the officers and the rules, and the death toll was deemed surprisingly low given those premises.Political consequences

French Prime MinisterÉmile Combes

Émile Justin Louis Combes (; 6 September 183525 May 1921) was a French statesman and freemason who led the Bloc des gauches's cabinet from June 1902 to January 1905.

Career

Émile Combes was born in Roquecourbe, Tarn. He studied for the pri ...

, was accused of being partially responsible, because he agreed to allow the race to proceed. He tried to explain that he did not know cars could be so fast and dangerous.

He claimed to be against any restriction on the automotive makers, and both Parliament and Senate agreed with a formal vote in support of his decision.

Just a few days after the disaster, the newspapers lost interest in the Paris–Madrid race. The sport pages were all about another race, at the Ardennes racetrack the following June 22.

Notes and references

Sources

Donatella Biffignandi: "Parigi-Madrid 1903. Una corsa che non ebbe arrivo", Auto d'Epoca gennaio 2003

{{DEFAULTSORT:Paris-Madrid race Auto races 1903 in motorsport Motorsport in Europe Motorsport in France Motorsport in Spain May 1903 sports events