Palestinian militant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Palestinian fedayeen (from the

Palestinian fedayeen (from the

The words "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" have had different meanings to different people at various points in history. According to the Sakhr Arabic-English dictionary, ''fida'i''—the singular form of the plural ''fedayeen''—means "one who risks his life voluntarily" or "one who sacrifices himself". In their book, ''The Arab-Israeli Conflict'', Tony Rea and John Wright have adopted this more literal translation, translating the term fedayeen as "self-sacrificers".

In his essay, "The Palestinian Leadership and the American Media: Changing Images, Conflicting Results" (1995), R.S. Zaharna comments on the perceptions and use of the terms "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" in the 1970s, writing:

The words "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" have had different meanings to different people at various points in history. According to the Sakhr Arabic-English dictionary, ''fida'i''—the singular form of the plural ''fedayeen''—means "one who risks his life voluntarily" or "one who sacrifices himself". In their book, ''The Arab-Israeli Conflict'', Tony Rea and John Wright have adopted this more literal translation, translating the term fedayeen as "self-sacrificers".

In his essay, "The Palestinian Leadership and the American Media: Changing Images, Conflicting Results" (1995), R.S. Zaharna comments on the perceptions and use of the terms "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" in the 1970s, writing:

On 29 October 1956, the first day of Israel's invasion of the Sinai Peninsula, Israeli forces attacked "fedayeen units" in the towns of Ras al-Naqb and Kuntilla. Two days later, fedayeen destroyed water pipelines in Kibbutz Ma'ayan along the Lebanese border, and began a campaign of mining in the area which lasted throughout November. In the first week of November, similar attacks occurred along the Syrian and Jordanian borders, the Jerusalem corridor and in the Wadi Ara region—although the state armies of both those countries are suspected as the saboteurs. On 9 November, four Israeli soldiers were injured after their vehicle was ambushed by fedayeen near the city of

On 29 October 1956, the first day of Israel's invasion of the Sinai Peninsula, Israeli forces attacked "fedayeen units" in the towns of Ras al-Naqb and Kuntilla. Two days later, fedayeen destroyed water pipelines in Kibbutz Ma'ayan along the Lebanese border, and began a campaign of mining in the area which lasted throughout November. In the first week of November, similar attacks occurred along the Syrian and Jordanian borders, the Jerusalem corridor and in the Wadi Ara region—although the state armies of both those countries are suspected as the saboteurs. On 9 November, four Israeli soldiers were injured after their vehicle was ambushed by fedayeen near the city of

Fedayeen groups began joining the

Fedayeen groups began joining the

Financial donations and recruitment increased as many young Arabs, including thousands of non-Palestinians, joined the ranks of the organization. The ruling

Financial donations and recruitment increased as many young Arabs, including thousands of non-Palestinians, joined the ranks of the organization. The ruling

Palestinian factions united by war

,

Palestinian fedayeen (from the

Palestinian fedayeen (from the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

''fidā'ī'', plural ''fidā'iyūn'', فدائيون) are militants or guerrillas of a nationalist orientation from among the Palestinian people

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

. Most Palestinians consider the fedayeen

Fedayeen ( ar, فِدائيّين ''fidāʼīyīn'' "self-sacrificers") is an Arabic term used to refer to various military groups willing to sacrifice themselves for a larger campaign.

Etymology

The term ''fedayi'' is derived from Arabic: '' ...

to be " freedom fighters", while most Israelis consider them to be "terrorists".

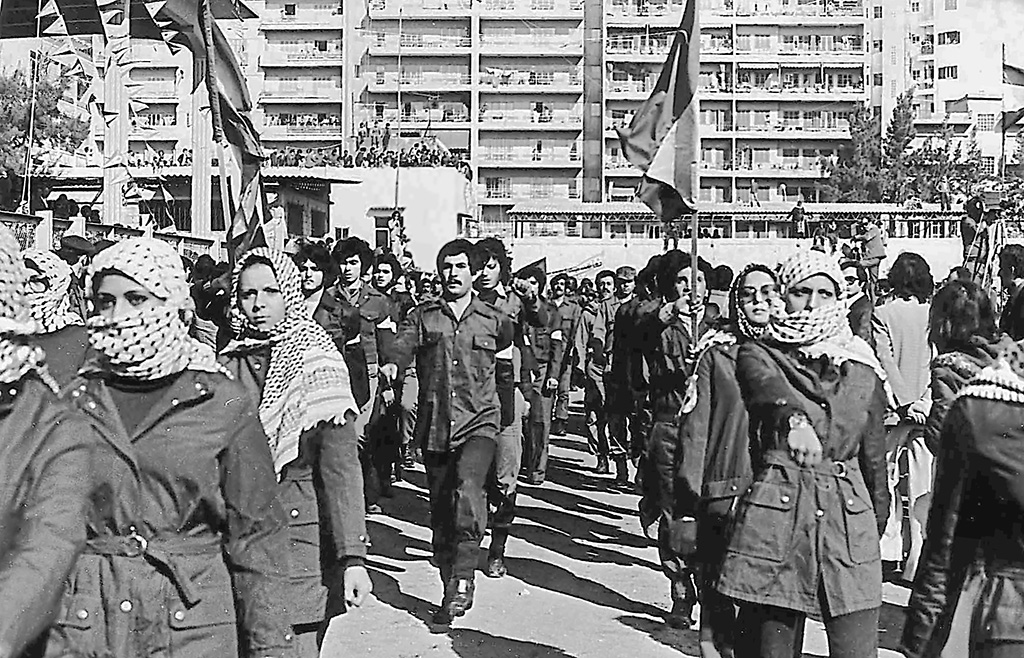

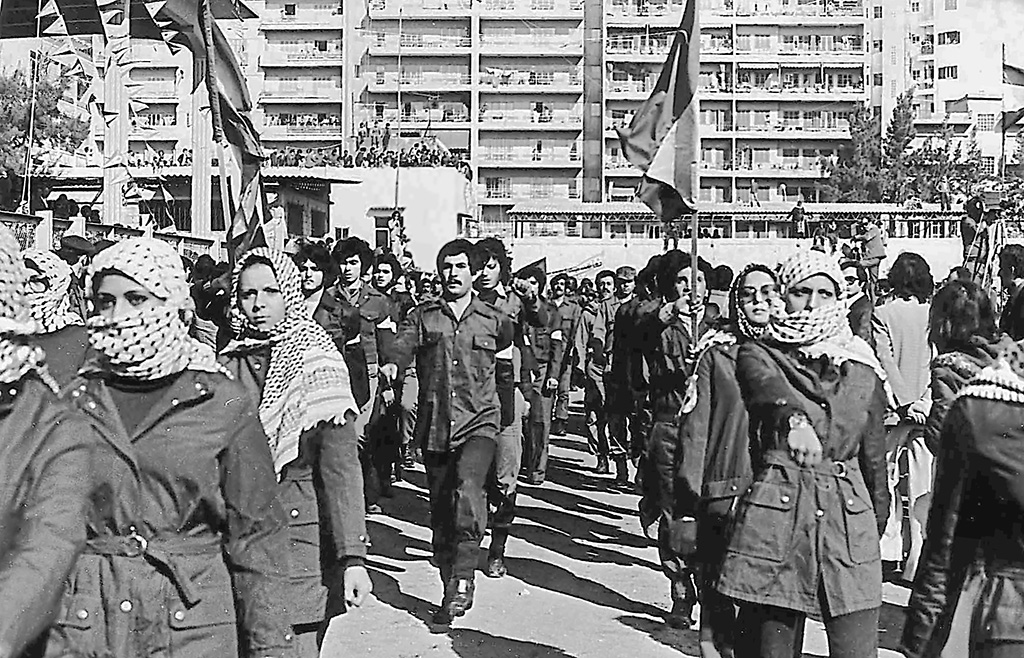

Considered symbols of the Palestinian national movement, the Palestinian fedayeen drew inspiration from guerrilla movements in Vietnam, China, Algeria and Latin America. The ideology of the Palestinian fedayeen was mainly left-wing nationalist, socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

or communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

, and their proclaimed purpose was to defeat Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

, claim Palestine and establish it as "a secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

, democratic, nonsectarian

Nonsectarian institutions are secular institutions or other organizations not affiliated with or restricted to a particular religious group.

Academic sphere

Examples of US universities that identify themselves as being nonsectarian include Adel ...

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

". The meaning of secular, democratic and non-sectarian, however, greatly diverged among fedayeen factions.

Emerging from among the Palestinian refugees who fled or were expelled from their villages as a result of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

,Almog, 2003, p. 20. in the mid-1950s the fedayeen began mounting cross-border operations

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders ca ...

into Israel from Syria, Egypt and Jordan. The earliest infiltrations were often to access the land's agricultural products they had lost as a result of the war, or to attack Israeli military, and sometimes civilian targets. The Gaza Strip, the sole territory of the All-Palestine Protectorate

The All-Palestine Protectorate, or simply All-Palestine, also known as Gaza Protectorate and Gaza Strip, was a short-lived client state with limited recognition, corresponding to the area of the modern Gaza Strip, that was established in the are ...

—a Palestinian state declared in October 1948—became the focal point of the Palestinian fedayeen activity. Fedayeen attacks were directed on Gaza and Sinai borders with Israel, and as a result Israel undertook retaliatory actions, targeting the fedayeen that also often targeted the citizens of their host countries, which in turn provoked more attacks.

Fedayeen actions were cited by Israel as one of the reasons for its launching of the Sinai Campaign of 1956, the 1967 War, and the 1978

Events January

* January 1 – Air India Flight 855, a Boeing 747 passenger jet, crashes off the coast of Bombay, killing 213.

* January 5 – Bülent Ecevit, of CHP, forms the new government of Turkey (42nd government).

* January 6 ...

and 1982 invasions of Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

. Palestinian fedayeen groups were united under the umbrella the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establishing Arab unity and sta ...

after the defeat of the Arab armies in the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

, though each group retained its own leader and independent armed forces.

Definitions of the term

The words "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" have had different meanings to different people at various points in history. According to the Sakhr Arabic-English dictionary, ''fida'i''—the singular form of the plural ''fedayeen''—means "one who risks his life voluntarily" or "one who sacrifices himself". In their book, ''The Arab-Israeli Conflict'', Tony Rea and John Wright have adopted this more literal translation, translating the term fedayeen as "self-sacrificers".

In his essay, "The Palestinian Leadership and the American Media: Changing Images, Conflicting Results" (1995), R.S. Zaharna comments on the perceptions and use of the terms "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" in the 1970s, writing:

The words "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" have had different meanings to different people at various points in history. According to the Sakhr Arabic-English dictionary, ''fida'i''—the singular form of the plural ''fedayeen''—means "one who risks his life voluntarily" or "one who sacrifices himself". In their book, ''The Arab-Israeli Conflict'', Tony Rea and John Wright have adopted this more literal translation, translating the term fedayeen as "self-sacrificers".

In his essay, "The Palestinian Leadership and the American Media: Changing Images, Conflicting Results" (1995), R.S. Zaharna comments on the perceptions and use of the terms "Palestinian" and "fedayeen" in the 1970s, writing:

''Palestinian'' became synonymous with ''terrorists'', '' skyjackers'', ''Edmund Jan Osmańczyk's ''Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements'' (2002) defines fedayeen as " Palestinian resistance fighters", whereas Martin Gilbert's ''The Routledge Atlas of the Arab-Israeli Conflict'' (2005) defines fedayeen as "Palestinian terrorist groups".commando Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...s'', and ''guerrillas''. The term ''fedayeen'' was often used but rarely translated. This added to the mysteriousness of Palestinian groups. Fedayeen means "freedom fighter." Mohammed al-Nawaway uses Zaharna translation of fedayeen as "freedom fighters" in his book ''The Israeli-Egyptian Peace Process in the Reporting of Western Journalists'' (2002).

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the ...

refers to the fedayeen simply as "guerrillas", as do Zeev Schiff

Ze'ev Schiff ( he, זאב שיף; 1 July 1932 - 19 June 2007) was an Israeli journalist and military correspondent for ''Haaretz''.

Schiff moved to Mandatory Palestine with his family in 1935. He studied Middle Eastern affairs and military h ...

and Raphael Rothstein in their work ''Fedayeen: Guerrillas Against Israel'' (1972). Fedayeen can also be used to refer to militant or guerrilla groups that are not Palestinian. (See Fedayeen

Fedayeen ( ar, فِدائيّين ''fidāʼīyīn'' "self-sacrificers") is an Arabic term used to refer to various military groups willing to sacrifice themselves for a larger campaign.

Etymology

The term ''fedayi'' is derived from Arabic: '' ...

for more.)

Beverly Milton-Edwards describes the Palestinian fedayeen as "modern revolutionaries fighting for national liberation, not religious salvation," distinguishing them from mujahaddin

''Mujahideen'', or ''Mujahidin'' ( ar, مُجَاهِدِين, mujāhidīn), is the plural form of ''mujahid'' ( ar, مجاهد, mujāhid, strugglers or strivers or justice, right conduct, Godly rule, etc. doers of jihād), an Arabic term t ...

(i.e. "fighters of the jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

"). While the fallen soldiers of both mujahaddin and fedayeen are called shahid

''Shaheed'' ( , , ; pa, ਸ਼ਹੀਦ) denotes a martyr in Islam. The word is used frequently in the Quran in the generic sense of "witness" but only once in the sense of "martyr" (i.e. one who dies for his faith); ...

(i.e. "martyrs") by Palestinians, Milton nevertheless contends that it would be political and religious blasphemy to call the "leftist fighters" of the fedayeen.

History

1948 to 1956

Palestinian immigration into Israel first emerged among thePalestinian refugee

Palestinian refugees are citizens of Mandatory Palestine, and their descendants, who fled or were expelled from their country over the course of the 1947–49 Palestine war (1948 Palestinian exodus) and the Six-Day War (1967 Palestinian exodu ...

s of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, living in camps Camps may refer to:

People

*Ramón Camps (1927–1994), Argentine general

*Gabriel Camps (1927–2002), French historian

*Luís Espinal Camps (1932–1980), Spanish missionary to Bolivia

* Victoria Camps (b. 1941), Spanish philosopher and professo ...

in Jordan (including the Jordanian-occupied West Bank), Lebanon, Egypt (including the Egyptian protectorate in Gaza), and Syria. Initially, most infiltrations were economic in nature, with Palestinians crossing the border seeking food or the recovery of property lost in the 1948 war.

Between 1948 and 1955, immigration by Palestinians into Israel was opposed by Arab governments, in order to prevent escalation into another war. The problem of establishing and guarding the demarcation line separating the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

from the Israeli-held Negev area proved vexing, largely due to the presence of over 200,000 Palestinian Arab refugees in this Gaza area. The terms of the Armistice Agreement restricted Egypt's use and deployment of regular armed forces in the Gaza strip. In keeping with this restriction, the Egyptian Government's solution was to form a Palestinian para-military police force. The Palestinian Border police was created in December 1952. The Border police were placed under the command of 'Abd-al-Man'imi 'Abd-al-Ra'uf, a former Egyptian air brigade commander, member of the Muslim Brotherhood and member of the Revolutionary Council. 250 Palestinian volunteers started training in March 1953, with further volunteers coming forward for training in May and December 1953. Some Border police personnel were attached to the Military Governor's office, under 'Abd-al-'Azim al-Saharti, to guard public installations in the Gaza strip. After an Israeli raid on an Egyptian military

The Egyptian Armed Forces ( arz, القُوّات المُسَلَّحَة المِصْرِيَّة, alquwwat almusalahat almisria) are the military forces of the Arab Republic of Egypt. They consist of the Egyptian Army, Egyptian Navy, Egyptia ...

outpost in Gaza in February 1955, during which 37 Egyptian soldiers were killed, the Egyptian government began to actively sponsor fedayeen raids into Israel.

The first struggle by Palestinian fedayeen may have been launched from Syrian territory in 1951, though most counterattacks between 1951 and 1953 were launched from Jordanian territory. According to Yeshoshfat Harkabi (former head of Israeli military intelligence), these early infiltrations were limited "incursions", initially motivated by economic reasons, such as Palestinians crossing the border into Israel to harvest crops in their former villages. Gradually, they developed into violent robbery and deliberate 'terrorist' attacks as fedayeen replaced the 'innocent' refugees as the perpetrators.

In 1953, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

tasked Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon (; ; ; also known by his diminutive Arik, , born Ariel Scheinermann, ; 26 February 1928 – 11 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

S ...

, then security chief of the Northern Region, with setting up of a new commando unit, Unit 101

Commando Unit 101 ( he, יחידה 101) was a special forces unit of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), founded and commanded by Ariel Sharon on orders from Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in August 1953. They were armed with non-standard weapons ...

, designed to respond to fedayeen infiltrations (''see retribution operations

Reprisal operations ( he, פעולות התגמול, ') were raids carried out by the Israel Defense Forces in the 1950s and 1960s in response to frequent fedayeen attacks during which armed Arab militants infiltrated Israel from Syria, Egyp ...

''). After one month of training, "a patrol of the unit that infiltrated into the Gaza Strip as an exercise, encountered Palestinians in al-Bureij refugee camp, opened fire to rescue itself and left behind about 30 killed Arabs and dozens of wounded." In its five-month existence, Unit 101 was also responsible for carrying out the Qibya massacre on the night of 14–15 October 1953, in the Jordanian village of the same name. Cross-border operations by Israel were conducted in both Egypt and Jordan "to 'teach' the Arab leaders that the Israeli government

The Cabinet of Israel (officially: he, ממשלת ישראל ''Memshelet Yisrael'') exercises executive authority in the State of Israel. It consists of ministers who are chosen and led by the prime minister. The composition of the governmen ...

saw them as responsible for these activities, even if they had not directly conducted them." Moshe Dayan

Moshe Dayan ( he, משה דיין; 20 May 1915 – 16 October 1981) was an Israeli military leader and politician. As commander of the Jerusalem front in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces (1953–1958) dur ...

felt that retaliatory action by Israel was the only way to convince Arab countries

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western As ...

that, for the safety of their own citizens, they should work to stop fedayeen infiltrations. Dayan stated, "We are not able to protect every man, but we can prove that the price for Jewish blood is high."

According to Martin Gilbert, between 1951 and 1955, 967 Israelis were killed in what he claims as "Arab terrorist attacks", a figure Benny Morris characterizes as "pure nonsense". Morris explains that Gilbert's fatality figures are "3-5 times higher than the figures given in contemporary Israeli reports" and that they seem to be based on a 1956 speech by David Ben-Gurion in which he uses the word ''nifga'im'' to refer to "casualties" in the broad sense of the term (i.e. both dead and wounded). According to the Jewish Agency for Israel

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

between 1951 and 1956, 400 Israelis were killed and 900 wounded in fedayeen attacks. Dozens of these attacks are today cited by the Israeli government as "Major Arab Terrorist Attacks against Israelis prior to the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

".

United Nations reports indicate that between 1949 and 1956, Israel launched more than seventeen raids on Egyptian territory and 31 attacks on Arab towns or military forces.

From late 1954 onwards, larger scale Fedayeen operations were mounted from Egyptian territory. The Egyptian government supervised the establishment of formal fedayeen groups in Gaza and the northeastern Sinai. General Mustafa Hafez, commander of Egyptian army intelligence, is said to have founded Palestinian fedayeen units "to launch terrorist raids across Israel's southern border," nearly always against civilians. In a speech on 31 August 1955, Egyptian President Nasser said:

:Egypt has decided to dispatch her heroes, the disciples of Pharaoh and the sons of Islam and they will cleanse the land of Palestine....There will be no peace on Israel's border because we demand vengeance, and vengeance is Israel's death.

In 1955, it is reported that 260 Israeli citizens were killed or wounded by the fedayeen. Some believe fedayeen attacks contributed to the outbreak of the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

; they were cited by Israel as the reason for undertaking the 1956 Sinai Campaign. Others argue that Israel "engineered eve-of-war lies and deceptions.... to give Israel the excuse needed to launch its strike", such as presenting a group of "captured fedayeen" to journalists, who were in fact Israeli soldiers.

In 1956, Israeli troops

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

entered Khan Yunis

Khan Yunis ( ar, خان يونس, also spelled Khan Younis or Khan Yunus; translation: ''Caravansary fJonah'') is a city in the southern Gaza Strip. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Khan Yunis had a population of 142,6 ...

in the Egyptian controlled Gaza Strip, conducting house-to-house searches for Palestinian fedayeen and weaponry. During this operation, 275 Palestinians were killed, with an additional 111 killed in Israeli raids on the Rafah

Rafah ( ar, رفح, Rafaḥ) is a Palestinian city in the southern Gaza Strip. It is the district capital of the Rafah Governorate, located south of Gaza City. Rafah's population of 152,950 (2014) is overwhelmingly made up of former Palestini ...

refugee camp. Israel claimed these killings resulted from "refugee resistance", a claim denied by refugees; there were no Israeli casualties.

Suez Crisis

On 29 October 1956, the first day of Israel's invasion of the Sinai Peninsula, Israeli forces attacked "fedayeen units" in the towns of Ras al-Naqb and Kuntilla. Two days later, fedayeen destroyed water pipelines in Kibbutz Ma'ayan along the Lebanese border, and began a campaign of mining in the area which lasted throughout November. In the first week of November, similar attacks occurred along the Syrian and Jordanian borders, the Jerusalem corridor and in the Wadi Ara region—although the state armies of both those countries are suspected as the saboteurs. On 9 November, four Israeli soldiers were injured after their vehicle was ambushed by fedayeen near the city of

On 29 October 1956, the first day of Israel's invasion of the Sinai Peninsula, Israeli forces attacked "fedayeen units" in the towns of Ras al-Naqb and Kuntilla. Two days later, fedayeen destroyed water pipelines in Kibbutz Ma'ayan along the Lebanese border, and began a campaign of mining in the area which lasted throughout November. In the first week of November, similar attacks occurred along the Syrian and Jordanian borders, the Jerusalem corridor and in the Wadi Ara region—although the state armies of both those countries are suspected as the saboteurs. On 9 November, four Israeli soldiers were injured after their vehicle was ambushed by fedayeen near the city of Ramla

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

; and several water pipelines and bridges were sabotaged in the Negev.

During the invasion of Sinai, Israeli forces killed fifty defenseless fedayeen on a lorry in Ras Sudar. (Reserve Lieutenant Colonel Saul Ziv told ''Maariv

''Maariv'' or ''Maʿariv'' (, ), also known as ''Arvit'' (, ), is a Jewish prayer service held in the evening or night. It consists primarily of the evening ''Shema'' and '' Amidah''.

The service will often begin with two verses from Psalms ...

'' in 1995 he was haunted by this killing.) After Israel took control of the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

, dozens of fedayeen were summarily executed, mostly in two separate incidents. Sixty-six were killed in screening operations in the area; while a US diplomat estimated that of the 500 fedayeen captured by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), "about 30" were killed.

1956 to 1967

Between the 1956 war and the 1967 war, Israeli civilian and military casualties on all Arab fronts, inflicted by regular and irregular forces (including those of Palestinian fedayeen), averaged one per month — an estimated total of 132 fatalities. During the mid and late 1960s, there emerged a number of independent Palestinian fedayeen groups who sought "the liberation of all Palestine through a Palestinian armed struggle." The first incursion by these fedayeen may have been the 1 January 1965 commando infiltration into Israel, to plant explosives that destroyed a section of pipeline designed to divert water from theJordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

into Israel. In 1966, the Israeli military attacked the Jordanian-controlled West Bank village of Samu, in response to Fatah

Fatah ( ar, فتح '), formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist social democratic political party and the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and s ...

raids against Israel's eastern border, increasing tensions leading to the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

.

1967 to 1987

Fedayeen groups began joining the

Fedayeen groups began joining the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establishing Arab unity and sta ...

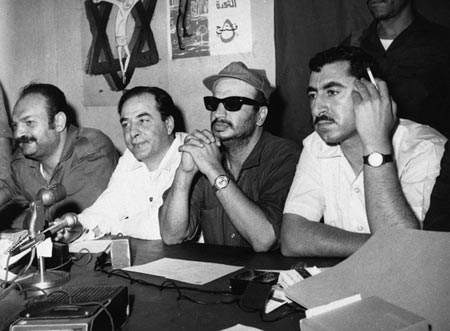

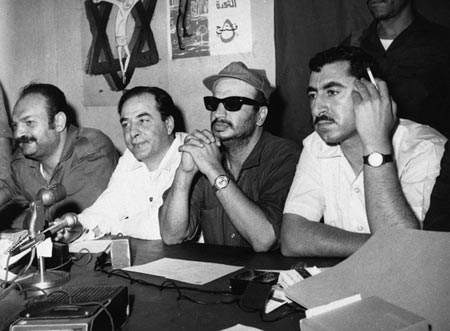

(PLO) in 1968. While the PLO was the "unifying framework" under which these groups operated, each fedayeen organization had its own leader and armed forces and retained autonomy in operations. Of the dozen or so fedayeen groups under the PLO framework, the most important were the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine ( ar, الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, translit=al-Jabhah al-Sha`biyyah li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, PFLP) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary so ...

(PFLP) headed by George Habash

George Habash ( ar, جورج حبش, Jūrj Ḥabash), also known by his laqab "al-Hakim" ( ar, الحكيم, al-Ḥakīm, "the wise one" or "the doctor"; 2 August 1926 – 26 January 2008) was a Palestinian Christian politician who founded th ...

, the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP; ar, الجبهة الديموقراطية لتحرير فلسطين, ''al-Jabha al-Dīmūqrāṭiyya li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn'') is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist organi ...

(DFLP) headed by Nayef Hawatmeh

Nayef Hawatmeh ( ar, نايف حواتمة, Nāyef Ḥawātmeh, Kunya: Abu an-Nuf) is a Jordanian politician who was active in the Palestinian political life.

Hawatmeh hails from a Jordanian clan and is a practicing Greek Catholic. He is th ...

, the PFLP-General Command headed by Ahmed Jibril

Ahmed Jibril ( ar, أحمد جبريل; April 1937 – 7 July 2021) was a Palestinian militant, the founder and leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC).

During the Syrian Civil War, Jibril wa ...

, as-Sa'iqa (affiliated with Syria), and the Arab Liberation Front (backed by Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

).

The most severe act of sabotage of the fedayeen occurred on 4 July 1969, when a single militant placed three pounds of explosives under the manifold of eight pipelines carrying oil from the Haifa refinery

BAZAN Group, (ORL or BAZAN, ), formerly Oil Refineries Ltd., is an oil refining and petrochemicals company located in Haifa Bay, Israel. It operates the largest oil refinery in the country. ORL has a total oil refining capacity of approximatel ...

to the dockside. As a result of the explosion, three pipelines were temporarily out of commission and a fire destroyed over 1,500 tons of refined oil.

West Bank

In the late 1960s, attempts were made to organize fedayeen resistance cells among the refugee population in the West Bank. The stony and empty terrain of the West Bank mountains made the fedayeen easy to spot; and Israelicollective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

against the families of fighters resulted in the fedayeen being pushed out of the West Bank altogether, within a few months. Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

reportedly escaped arrest in Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ar, رام الله, , God's Height) is a Palestinian city in the central West Bank that serves as the ''de facto'' administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerus ...

by jumping out a window, as Israeli police

The Israel Police ( he, משטרת ישראל, ''Mišteret Yisra'el''; ar, شرطة إسرائيل, ''Shurtat Isrāʼīl'') is the civilian police force of Israel. As with most other police forces in the world, its duties include crime fight ...

came in the front door. Without a base in the West Bank, and prevented from operating in Syria and Egypt, the fedayeen concentrated in Jordan.

Jordan

After the influx of a second wave ofPalestinian refugees

Palestinian refugees are citizens of Mandatory Palestine, and their descendants, who fled or were expelled from their country over the course of the 1947–49 Palestine war (1948 Palestinian exodus) and the Six-Day War ( 1967 Palestinian exodu ...

from the 1967 war, fedayeen bases in Jordan began to proliferate, and there were increased fedayeen attacks on Israel. Fedayeen fighters launched ineffective bazooka-shelling attacks on Israeli targets across the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

, while "brisk and indiscriminate" Israeli retaliations destroyed Jordanian villages, farms and installations, causing 100,000 people to flee the Jordan Valley eastward. The increasing ferocity of those Israeli reprisals directed at Jordanians (not Palestinians) for fedayeen raids into Israel became a growing cause of concern for the Jordanian authorities.

One such Israeli reprisal was in the Jordanian town of Karameh

Al-Karameh ( ar, الكرامة), or simply Karameh, is a town in west-central Jordan, near the Allenby Bridge which spans the Jordan River. Karameh sits on the eastern bank of the river, along the border between Jordan, Israel, as well as the Is ...

, home to the headquarters of an emerging fedayeen group called Fatah

Fatah ( ar, فتح '), formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist social democratic political party and the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and s ...

, led by Yasser Arafat. Warned of large-scale Israeli military preparations, many fedayeen groups, including the PFLP and the DFLP, withdraw their forces from the town. Advised by a pro-Fatah Jordanian divisional commander to withdraw his men and headquarters to nearby hills, Arafat refused, stating "We want to convince the world that there are those in the Arab world who will not withdraw or flee." Fatah remained, and the Jordanian Army

The Royal Jordanian Army (Arabic: القوّات البرية الاردنيّة; ) is the Army, ground force branch of the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF). It draws its origins from units such as the Arab Legion, formed in the Emirate of Transjord ...

agreed to back them if heavy fighting ensued.

On the night of 21 March 1968, Israel attacked Karameh with heavy weaponry, armored vehicles and fighter jets. Fatah held its ground, surprising the Israeli military. As Israel's forces intensified their campaign, the Jordanian Army became involved, causing the Israelis to retreat in order to avoid a full-scale war. By the battle's end, 100 Fatah militants had been killed, 100 wounded and 120-150 captured; Jordanian fatalities were 61 soldiers and civilians, 108 wounded; and Israeli casualties were 28 soldiers killed and 69 wounded. 13 Jordanian tanks were destroyed in the battle; while the Israelis lost 4 tanks, 3 half tracks, 2 armoured cars, and an airplane shot down by Jordanian forces.

The Battle of Karameh raised the profile of the fedayeen, as they were regarded the "daring heroes of the Arab world". Despite the higher Arab death toll, Fatah considered the battle a victory because of the Israeli army's rapid withdrawal. Such developments prompted Rashid Khalidi to dub the Battle of Karameh the "foundation myth" of the Palestinian commando movement, whereby "failure against overwhelming odds asbrilliantly narrated as nheroic triumph."

Financial donations and recruitment increased as many young Arabs, including thousands of non-Palestinians, joined the ranks of the organization. The ruling

Financial donations and recruitment increased as many young Arabs, including thousands of non-Palestinians, joined the ranks of the organization. The ruling Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

authorities in Jordan grew increasingly alarmed by the PLO's activities, as they established a "state within a state", providing military training

Military education and training is a process which intends to establish and improve the capabilities of military personnel in their respective roles. Military training may be voluntary or compulsory duty. It begins with recruit training, procee ...

and social welfare services to the Palestinian population, bypassing the Jordanian authorities. Palestinian criticism of the poor performance of the Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

(the King's army) was an insult to both the King and the regime. Further, many Palestinian fedayeen groups of the radical left, such as the PFLP, "called for the overthrow of the Arab monarchies, including the Hashemite regime in Jordan, arguing that this was an essential first step toward the liberation of Palestine."

In the first week of September 1970, PFLP forces hijacked three airplanes (British, Swiss and German) at Dawson's field in Jordan. To secure the release of the passengers, the demand to free PFLP militants held in European jails was met. After everyone had disembarked, the fedayeen destroyed the airplanes on the tarmac.

Black September in Jordan

On 16 September 1970,King Hussein

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family o ...

ordered his troops to strike and eliminate the fedayeen network in Jordan. Syrian troops intervened to support the fedayeen, but were turned back by Jordanian armour and Israeli army overflights. Thousands of Palestinians were killed in the initial battle — which came to be known as Black September

Black September ( ar, أيلول الأسود; ''Aylūl Al-Aswad''), also known as the Jordanian Civil War, was a conflict fought in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan between the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF), under the leadership of King Hussein ...

— and thousands more in the security crackdown that followed. By the summer of 1971, the Palestinian fedayeen network in Jordan had been effectively dismantled, with most of the fighters setting up base in southern Lebanon instead.

Gaza Strip

The emergence of a fedayeen movement in theGaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

was catalyzed by Israel's occupation of the territory during the 1967 war. Palestinian fedayeen from Gaza "waged a mini-war" against Israel for three years before the movement was crushed by the Israeli military in 1971 under the orders of then Defense Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in s ...

, Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon (; ; ; also known by his diminutive Arik, , born Ariel Scheinermann, ; 26 February 1928 – 11 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

S ...

.

Palestinians in Gaza were proud of their role in establishing a fedayeen movement there when no such movement existed in the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

at the time. The fighters were housed in refugee camps or hid in the citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes. The genus ''Citrus'' is native to ...

groves of wealthy Gazan landowners, carrying out raids against Israeli soldiers from these sites.

The most active of the fedayeen groups in Gaza was the PFLP, an offshoot of the Arab Nationalist Movement

The Arab Nationalist Movement ( ar, حركة القوميين العرب, ''Harakat al-Qawmiyyin al-Arab''), also known as the Movement of Arab Nationalists and the Harakiyyin, was a pan-Arab nationalist organization influential in much of the Ara ...

(ANM)—who enjoyed instant popularity among the already secularized, socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

population who had come of age during Egyptian President Nasser's rule of Gaza. The emergence of armed struggle as the liberation strategy for the Gaza Strip reflected larger ideological changes within the Palestinian national movement toward political violence.

The ideology of armed struggle was, by this time, broadly secular in content; Palestinians were asked to take up arms not as part of aThe "radical left" dominated the political scene, and the overarching slogan of the time was, "We will liberate Palestine first, then the rest of the Arab world." During Israel's 1971 military campaign to contain or control the fedayeen, an estimated 15,000 suspected fighters were rounded up and deported to detention camps in Abu Zneima and Abu Rudeis in the Sinai. Dozens of homes werejihad Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...against the infidel but to free the oppressed from the Zionist colonial regime. The vocabulary of liberation was distinctly secular.

demolished

Demolition (also known as razing, cartage, and wrecking) is the science and engineering in safely and efficiently tearing down of buildings and other artificial structures. Demolition contrasts with deconstruction, which involves taking a b ...

by Israeli forces, rendering hundreds of people homeless. According to Milton-Edwards, "This security policy successfully instilled terror in the camps and wiped out the fedayeen bases." The destruction of the secular infrastructure, paved the way for the rise of the Islamic movement, which began organizing as early as 1969–1970, led by Sheikh Ahmed Yassin

Sheikh Ahmed Ismail Hassan Yassin ( ar, الشيخ أحمد إسماعيل حسن ياسين; 1 January 1937 – 22 March 2004) was a Palestinian politician and imam who founded Hamas, a militant Islamist and Palestinian nationalist organiza ...

.

Lebanon

On 3 November 1969, the Lebanese government signed the Cairo Agreement which granted Palestinians the right to launch attacks on Israel from southern Lebanon in coordination with theLebanese Army

)

, founded = 1 August 1945

, current_form = 1991

, disbanded =

, branches = Lebanese Ground Forces Lebanese Air ForceLebanese Navy

, headquarters = Yarze, Lebanon

, flying_hours =

, websit ...

. After the expulsion of the Palestinian fedayeen from Jordan and a series of Israeli raids on Lebanon, the Lebanese government granted the PLO the right to defend Palestinian refugee camps there and to possess heavy weaponry. After the outbreak of 1975 Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ar, الحرب الأهلية اللبنانية, translit=Al-Ḥarb al-Ahliyyah al-Libnāniyyah) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 120,000 fatalities a ...

, the PLO increasingly began to act once again as a "state within a state". On 11 March 1978, twelve fedayeen led by Dalal Mughrabi infiltrated Israel from the sea and hijacked a bus along the coastal highway, killing 38 civilians in the ensuing gunfight between them and police. Israel invaded southern Lebanon in the 1978 Israel-Lebanon conflict, occupying a wide area there to put an end to Palestinian attacks on Israel, but fedayeen rocket strikes on northern Israel continued.

Israeli armoured artillery and infantry forces, supported by air force and naval units again entered Lebanon on 6 June 1982 in an operation code-named "Peace for Galilee", encountering "fierce resistance" from the Palestinian fedayeen there. Israel's occupation of southern Lebanon and its siege and constant shelling of the capital Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

in the 1982 Lebanon War

The 1982 Lebanon War, dubbed Operation Peace for Galilee ( he, מבצע שלום הגליל, or מבצע של"ג ''Mivtsa Shlom HaGalil'' or ''Mivtsa Sheleg'') by the Israeli government, later known in Israel as the Lebanon War or the First L ...

, eventually forced the Palestinian fedayeen to accept an internationally brokered agreement that moved them out of Lebanon to different places in the Arab world. The headquarters of the PLO was moved out of Lebanon to Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

at this time. The new PLO headquarters was destroyed during an Israeli airstrike

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The off ...

in 1985.

During a September 2, 1982 press conference at the United Nations, Yasser Arafat stated that, "Jesus Christ was the first Palestinian fedayeen who carried his sword along the path on which the Palestinians today carry their cross."

First Intifada

On 25 November 1987, PFLP-GC launched an attack, in which two fedayeen infiltrated northern Israel from an undisclosed Syrian-controlled area in southern Lebanon with hang gliders. One of them was killed at the border, while the other proceeded to land at an army camp, initially killing a soldier in a passing vehicle, then five more in the camp, before being shot dead.Thomas Friedman

Thomas Loren Friedman (; born July 20, 1953) is an American political commentator and author. He is a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner who is a weekly columnist for '' The New York Times''. He has written extensively on foreign affairs, global ...

said that judging by commentary in the Arab world, the raid was seen as a boost to the Palestinian national movement, just as it had seemed to be almost totally eclipsed by the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Counci ...

. Palestinians in Gaza began taunting Israeli soldiers, chanting "six to one" and the raid has been noted as a catalyst to the First Intifada

The First Intifada, or First Palestinian Intifada (also known simply as the intifada or intifadah),The word ''wikt:intifada, intifada'' () is an Arabic word meaning "wikt:uprising, uprising". Its strict Arabic transliteration is '. was a sus ...

.

During the First Intifada, armed violence on the part of Palestinians was kept to a minimum, in favor of mass demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

. However, the issue of the role of armed struggle did not die out altogether. Those Palestinian groups affiliated with the PLO and based outside of historic Palestine, such as rebels within Fatah and the PFLP-GC, used the lack of fedayeen operations as their main weapon of criticism against the PLO leadership at the time. The PFLP and DFLP even made a few abortive attempts at fedayeen operations inside Israel. According to Jamal Raji Nassar and Roger Heacock,

..at least parts of the Palestinian left sacrificed all to the golden calf of armed struggle when measuring the degree of revolutionary commitment by the number of fedayeen operations, instead of focusing on the positions of power they doubtless held inside theDuring the First Intifada, but particularly after the signing of theOccupied Territories Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...and which were major assets in struggles over a particular political line.

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993;

, the fedayeen steadily lost ground to the emerging forces of the mujaheddin, represented initially and most prominently by Hamas. The fedayeen lost their position as a political force and the secular nationalist movement

The Nationalist Movement is a Mississippi-founded white nationalist organization with headquarters in Georgia that advocates what it calls a "pro-majority" position. It has been called white supremacist by the Associated Press and Anti-Defamati ...

that had represented the first generation of the Palestinian resistance became instead a symbolic, cultural force that was seen by some as having failed in its duties.

Second Intifada and current situation

After being dormant for many years, Palestinian fedayeen reactivated their operations during theSecond Intifada

The Second Intifada ( ar, الانتفاضة الثانية, ; he, האינתיפאדה השנייה, ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada ( ar, انتفاضة الأقصى, label=none, '), was a major Palestinian uprising against Israel ...

. In August 2001, ten Palestinian commandos from the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP; ar, الجبهة الديموقراطية لتحرير فلسطين, ''al-Jabha al-Dīmūqrāṭiyya li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn'') is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist organi ...

(DFLP) penetrated the electric fences of the fortified army base of Bedolah

Bedolah ( he, בְּדֹלַח, ''lit.'' Crystal) was an Israeli settlement and army base in the Gush Katif settlement bloc, located in the southwest edge of the Gaza Strip. Home to 220 religious Jews, its inhabitants were evicted, its houses d ...

, killing an Israeli major and two soldiers and wounding seven others. One of the commandos was killed in the firefight. Another was tracked for hours and later shot in head, while the rest escaped. In Gaza, the attack produced "a sense of euphoria—and nostalgia for the Palestinian fedayeen raids in the early days of the Jewish state." Israel responded by launching airstrikes at the police headquarters in Gaza City, an intelligence building in the central Gaza town of Deir al-Balah

Deir al-Balah or Deir al Balah ( ar, دير البلح, , Monastery of the Date Palm) is a Palestinian city in the central Gaza Strip and the administrative capital of the Deir el-Balah Governorate. It is located over south of Gaza City. The c ...

and a police building in the West Bank town of Salfit. Salah Zeidan, head of the DFLP in Gaza, stated of the operation that, "It's a classic model—soldier to soldier, gun to gun, face to face ..Our technical expertise has increased in recent days. So has our courage, and people are going to see that this is a better way to resist the occupation than suicide bombs inside the Jewish state."

Today, the fedayeen have been eclipsed politically by the Palestinian National Authority

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; ar, السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية '), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine,

(PNA), which consists of the major factions of the PLO, and militarily by Islamist groups, particularly Hamas

Hamas (, ; , ; an acronym of , "Islamic Resistance Movement") is a Palestinian Sunni- Islamic fundamentalist, militant, and nationalist organization. It has a social service wing, Dawah, and a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qas ...

. Already strained relations between Hamas and the PNA collapsed entirely when the former took over the Gaza Strip in 2007. Although the fedayeen are leftist and secular, during the 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict, fedayeen groups fought alongside and in coordination with Hamas even though a number of the factions were previously sworn enemies of them. The al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, an armed faction loyal to the Fatah-controlled PNA, undermined Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas

Mahmoud Abbas ( ar, مَحْمُود عَبَّاس, Maḥmūd ʿAbbās; born 15 November 1935), also known by the kunya Abu Mazen ( ar, أَبُو مَازِن, links=no, ), is the president of the State of Palestine and the Palestinian Nati ...

by lobbing rockets into southern Israel in concert with rivals Hamas and the Islamic Jihad. According to researcher Maha Azzam, this symbolized the disintegration of Fatah and the division between the grassroots organization and the current leadership. The PFLP and the Popular Resistance Committees

The Popular Resistance Committees (PRC) ( ar, لجان المقاومة الشعبية, ''Lijān al-Muqāwama al-Shaʿbiyya'') is a coalition of a number of armed Palestinian groups opposed to what they regard as the conciliatory approach of t ...

also joined in the fighting.

To rival the PNA and increase Palestinian fedayeen cooperation, a Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

-based coalition composed of representatives of Hamas, Islamic Jihad, the PFLP, as-Sa'iqa, the Palestinian Popular Struggle Front

The Palestinian Popular Struggle Front (PPSF, occasionally abbr. PSF), (Arabic: جبهة النضال الشعبي الفلسطيني, ''Jabhet Al-Nedal Al-Sha'abi Al-Falestini''), is a Palestinian political party. Samir Ghawshah was elected sec ...

, the Revolutionary Communist Party, and other anti-PNA factions within the PLO, such as Fatah al-Intifada, was established during the Gaza War in 2009.Bauer, ShanPalestinian factions united by war

,

Al-Jazeera English

Al Jazeera English (AJE; ar, الجزيرة, translit=al-jazīrah, , literally "The Peninsula", referring to the Qatar Peninsula) is an international 24-hour English-language news channel owned by the Al Jazeera Media Network, which is ow ...

. 2009-01-20.

Philosophical grounding and objectives

The objectives of the fedayeen were articulated in the statements and literature they produced, which were consistent with reference to the aim of destroying Zionism. In 1970, the stated aim of the fedayeen was establishing Palestine as "a secular, democratic, nonsectarian state." Bard O'Neill writes that for some fedayeen groups, the secular aspect of the struggle was "merely a slogan for assuaging world opinion," while others strove "to give the concept meaningful content." Prior to 1974, the fedayeen position was thatJews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

who renounced Zionism could remain in the Palestinian state to be created. After 1974, the issue became less clear and there were suggestions that only those Jews who were in Palestine prior to "the Zionist invasion", alternatively placed at 1947 or 1917, would be able to remain.

Bard O'Neill also wrote that the fedayeen attempted to study and borrow from all of the revolutionary models available, but that their publications and statements show a particular affinity for the Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

n, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

ese, and Chinese experiences.

Infighting and breakaway movements

During the post-Six-Day War era, individual fedayeen movements quarreled over issues about the recognition of Israel, alliances with various Arab states, and ideologies. A faction led byNayef Hawatmeh

Nayef Hawatmeh ( ar, نايف حواتمة, Nāyef Ḥawātmeh, Kunya: Abu an-Nuf) is a Jordanian politician who was active in the Palestinian political life.

Hawatmeh hails from a Jordanian clan and is a practicing Greek Catholic. He is th ...

and Yasser Abed Rabbo

Yasser Abed Rabbo ( ar, ياسر عبد ربه) also known by his '' kunya'', Abu Bashar ( ar, ابو بشار) (born 17 September 1945) is a Palestinian politician and a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization's (PLO) Executive Committee. ...

split from PFLP in 1974, because they preferred a Maoist

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

and non-Nasserist

Nasserism ( ) is an Arab nationalist and Arab socialist political ideology based on the thinking of Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, and Egypt's second President. Spanning the domestic an ...

approach. This new movement became known as the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP; ar, الجبهة الديموقراطية لتحرير فلسطين, ''al-Jabha al-Dīmūqrāṭiyya li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn'') is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist organi ...

(DFLP). In 1974, the PNC approved the Ten Point Program (drawn up by Arafat and his advisers), and proposed a compromise with the Israelis. The Program called for a Palestinian national authority over every part of "liberated Palestinian territory", which referred to areas captured by Arab forces in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

(present-day West Bank and Gaza Strip). Perceived by some Palestinians as overtures to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and concessions to Israel, the program fostered internal discontent, and prompted several of the PLO factions, such as the PFLP, DFLP, as-Sa'iqa, the Arab Liberation Front and the Palestine Liberation Front, among others, to form a breakaway movement which came to be known as the Rejectionist Front

The Rejectionist Front (Arabic: جبهة الرفض) or Front of the Palestinian Forces Rejecting Solutions of Surrender (جبهة القوى الفلسطينية الرافضة للحلول الإستسلامية) was a political coalition formed ...

.

During the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990), the PLO aligned itself with the Communist and Nasserist Lebanese National Movement. Although they were initially backed by Syrian president Hafez al-Assad

Hafez al-Assad ', , (, 6 October 1930 – 10 June 2000) was a Syrian statesman and military officer who served as President of Syria from taking power in 1971 until his death in 2000. He was also Prime Minister of Syria from 1970 to 1 ...

, when he switched sides in the conflict, the smaller pro-Syrian factions within the Palestinian fedayeen camp, namely as-Sa'iqa and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the tota ...

fought against Arafat's Fatah-led PLO. In 1988, after Arafat and al-Assad partially reconciled, Arafat loyalists in the refugee camps of Bourj al-Barajneh

Bourj el-Barajneh ( ar, برج البراجنة, lit=Tower of Towers) is a municipality located in the southern suburbs of Beirut, in Lebanon. The municipality lies between Beirut–Rafic Hariri International Airport and the town of Haret Hreik ...

and Shatila

The Shatila refugee camp ( ar, مخيم شاتيلا), also known as the Chatila refugee camp, is a settlement originally set up for Palestinian refugees in 1949. It is located in southern Beirut, Lebanon and houses more than 9,842 registered P ...

attempted to force out Fatah al-Intifada—a pro-Syrian Fatah breakaway movement formed by Said al-Muragha in 1983. Instead, al-Muragha's forces overran Arafat loyalists from both camps after bitter fighting in which Fatah al-Intifada received backing from the Lebanese Amal militia.

The PLO and other Palestinian armed movements became increasingly divided after the Oslo Accords in 1993. They were rejected by the PFLP, DFLP, Hamas, and twenty other factions, as well as Palestinian intellectuals, refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s outside of the Palestinian territories, and the local leadership of the territories. The Rejectionist fedayeen factions formed a common front with the Islamists, culminating in the creation of the Alliance of Palestinian Forces

The Alliance of Palestinian Forces ( ar, تحالف القوى الفلسطينية, abbreviated APF) is a loose Damascus-based alliance of eight Palestinian political factions. The Alliance was created in Damascus in December 1993 by ten Palesti ...

. This new alliance failed to act as a cohesive unit, but revealed the sharp divisions among the PLO, with the fedayeen finding themselves aligning with Palestinian Islamists for the first time. Disintegration within the PLO's main body Fatah increased as Farouk Qaddoumi

Faruq al-Qaddumi ( ar, فاروق القدومي; born 18 August 1931) or Farouk al-Kaddoumi, also known by the kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu al-Lutf, was until 2009 Secretary-General and between 2004 and 2009 Chairman of Fatah, Fatah's central commi ...

—in charge of foreign affairs—voiced his opposition to negotiations with Israel. Members of the PLO-Executive Committee, poet Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish ( ar, محمود درويش, Maḥmūd Darwīsh, 13 March 1941 – 9 August 2008) was a Palestinian poet and author who was regarded as the Palestinian national poet. He won numerous awards for his works. Darwish used Palestine ...

and refugee leader Shafiq al-Hout Shafiq, Shafik, Shafeeq, Shafique, Shafic, Chafic or Shafeek (Arabic: شفيق, Urdu: شفیق, Romanized: Shafīq) may refer to

* Shafiq (name)

* Shafiq Mill Colony, a neighbourhood of Gulberg Town in Karachi, Pakistan

*'' Charles Shafiq Karthiga< ...

resigned from their posts in response to the PLO's acceptance of Oslo's terms.

Tactics

Until 1968, fedayeen tactics consisted largely of hit-and-run raids on Israeli military targets. A commitment to "armed struggle" was incorporated into PLO Charter in clauses that stated: "Armed struggle is the only way to liberate Palestine" and "Commando action constitutes the nucleus of the Palestinian popular liberation war." Preceding the Six-Day War in 1967, the fedayeen carried out several campaigns of sabotage against Israeli infrastructure. Common acts of this included the consistent mining of water and irrigation pipelines along theJordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

and its tributaries, as well as the Lebanese-Israeli border and in various locations in the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

. Other acts of sabotage involved bombing bridges, mining roads, ambushing cars and vandalizing (sometimes destroying) houses. After the Six-Day War, these incidents steadily decreased with the exception of the bombing of a complex of oil pipelines sourcing from the Haifa refinery in 1969.

The IDFs counterinsurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionari ...

tactics, which from 1967 onwards regularly included the use of home demolitions, curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

s, deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

s, and other forms of collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

, effectively precluded the ability of the Palestinian fedayeen to create internal bases from which to wage "a people's war". The tendency among many captured guerrillas to collaborate

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. Most ...

with the Israeli authorities, providing information that led to the destruction of numerous "terrorist cells", also contributed to the failure to establish bases in the territories occupied by Israel. The fedayeen were compelled to establish external bases, resulting in frictions with their host countries which led to conflicts (such as Black September

Black September ( ar, أيلول الأسود; ''Aylūl Al-Aswad''), also known as the Jordanian Civil War, was a conflict fought in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan between the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF), under the leadership of King Hussein ...

), diverting them from their primary objective of "bleeding Israel".

Airplane hijackings

The tactic of exporting their struggle against Israel beyond the Middle East was first adopted by the Palestinian fedayeen in 1968. According to John Follain, it wasWadie Haddad

Wadie Haddad ( ar, وديع حداد; 1927 – 28 March 1978), also known as Abu Hani, was a Palestinian leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine's armed wing. He was responsible for organizing several civilian airplane ...

of the PFLP who, unconvinced with the effectiveness of raids on military targets, masterminded the first hijacking of a civilian passenger plane by Palestinian fedayeen in July 1968. Two commandos forced an El Al

El Al Israel Airlines Ltd. (, he, אל על נתיבי אויר לישראל בע״מ), trading as El Al (Hebrew: , "Upwards", "To the Skies" or "Skywards", stylized as ELAL; ar, إل-عال), is the flag carrier of Israel. Since its inaugura ...

Boeing 747 en route from Rome to Tel Aviv to land in Algiers, renaming the flight "Palestinian Liberation 007". While publicly proclaiming that it would not negotiate with terrorists, the Israelis did negotiate. The passengers were released unharmed in exchange for the release of sixteen Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails.

The first hijacking of an American airliner was conducted by the PFLP on 29 August 1969. Robert D. Kumamoto describes the hijacking as a response to an American veto of a United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

resolution censuring Israel for its March 1969 aerial attacks on Jordanian villages suspected of harbouring fedayeen, and for the impending delivery of American Phantom

Phantom may refer to:

* Spirit (animating force), the vital principle or animating force within all living things

** Ghost, the soul or spirit of a dead person or animal that can appear to the living

Aircraft

* Boeing Phantom Ray, a stealthy unm ...

jets to Israel. The flight, en route to Tel Aviv from Rome, was forced to land in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

where, Leila Khaled

Leila Khaled ( ar, ليلى خالد, born April 9, 1944) is a Palestinian refugee, terrorist, and member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

Khaled came to public attention for her role in the TWA Flight 840 hijacking ...

, one of the two fedayeen to hijack the plane proclaimed that, "this hijacking is one of the operational aspects of our war against Zionism and all who support it, including the United States ... it was a perfectly normal thing to do, the sort of thing all freedom fighters must tackle." Most of the passengers and crew were released immediately after the plane landed. Six Israeli passengers were taken hostage and held for questioning by Syria. Four women among them were released after two days, and the two men were released after a week of intensive negotiations between all the parties involved. Of this PFLP hijacking and those that followed at Dawson's field, Kumamoto writes: "The PFLP hijackers had seized no armies, mountaintops, or cities. Theirs was not necessarily a war of arms; it was a war of words – a war of propaganda, the exploitation of violence to attract world attention. In that regard, the Dawson's Field episode was a publicity goldmine."

George Habash, leader of the PFLP, explained his view of the efficacy of hijacking as a tactic in a 1970 interview, stating, "When we hijack a plane it has more effect than if we killed a hundred Israelis in battle." Habash also stated that after decades of being ignored, "At least the world is talking about us now." The hijacking attempts did indeed continue. On 8 May 1972, a Sabena Airlines 707 was forced to land in Tel Aviv after it was commandeered by four Black September commandos who demanded the release of 317 fedayeen fighters being held in Israeli jails. While the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

was negotiating, Israeli paratroopers disguised as mechanics stormed the plane, shot and killed two of hijackers and captured the remaining two after a gunfight that injured five passengers and two paratroopers.

The tactics employed by the Black September group in subsequent operations differed sharply from the other "run-of-the-mill PLO attacks of the day". The unprecedented level of violence evident in multiple international attacks between 1971 and 1972 included the Sabena airliner hijacking (mentioned above), the assassination of the Jordanian Prime Minister in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, the Massacre at Lod airport, and the Munich Olympics massacre

The Munich massacre was a terrorist attack carried out during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, West Germany, by eight members of the Palestinian people, Palestinian militant organization Black September Organization, Black September, who i ...

. In ''The Dynamics of Armed Struggle'', J. Bowyer Bell

J. Bowyer Bell (November 15, 1931 – August 23, 2003) was an American historian, artist and art critic. He was best known as a terrorism expert.

Background and early life

Bell was born into an Episcopalian family in 1931 in New York City. ...

contends that "armed struggle" is a message to the enemy that they are "doomed by history" and that operations are "violent message units" designed to "accelerate history" to this end. Bell argues that despite the apparent failure of the Munich operation which collapsed into chaos, murder, and gun battles, the basic fedayeen intention was achieved since, "The West was appalled and wanted to know the rationale of the terrorists, the Israelis were outraged and punished, many of the Palestinians were encouraged by the visibility and ignored the killings, and the rebels felt that they had acted, helped history along." He notes the opposite was true for the 1976 hijacking of an Air France flight redirected to Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

where the Israelis scored an "enormous tactical victory" in Operation Entebbe

Operation Entebbe, also known as the Entebbe Raid or Operation Thunderbolt, was a counter-terrorist hostage-rescue mission carried out by commandos of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) at Entebbe Airport in Uganda on 4 July 1976.

A week ear ...

. While their death as martyrs had been foreseen, the fedayeen had not expected to die as villains, "bested by a display of Zionist skill."

Affiliations with other guerrilla groups

Several fedayeen groups maintained contacts with a number of other guerrilla groups worldwide. The IRA for example had long held ties with Palestinians, and volunteers trained at fedayeen bases in Lebanon. In 1977, Palestinian fedayeen from Fatah helped arrange for the delivery of a sizable arms shipment to the Provos by way ofCyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, but it was intercepted by the Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

authorities.

The PFLP and the DFLP established connections with revolutionary groups such as the Red Army Faction

The Red Army Faction (RAF, ; , ),See the section "Name" also known as the Baader–Meinhof Group or Baader–Meinhof Gang (, , active 1970–1998), was a West German far-left Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group founded in 1970.

The ...

of West Germany, the Action Directe (armed group), Action Directe of France, the Red Brigades of Italy, the Japanese Red Army and the Tupamaros of Uruguay. These groups, especially the Japanese Red Army participated in many of the PFLP's operations including hijackings and the Lod Airport massacre. The Red Army Faction joined the PFLP in the hijackings of two airplanes that landed in Entebbe Airport.

See also