Owen D. Young on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Owen D. Young (October 27, 1874July 11, 1962) was an American industrialist, businessman, lawyer and diplomat at the Second Reparations Conference (SRC) in 1929, as a member of the German Reparations International Commission.

He is known for the plan to settle Germany's World War I reparations, known as the Young Plan and for the creation of the

In 1919, at the request of the government, he created the

In 1919, at the request of the government, he created the

online

on Young's role in Europe, pp 43–62.. * * * * Hammond, John Winthrop. ''Men and Volts, the Story of General Electric'', published 1941. Citations: came to Schenectady – 360; Chairman of the Board – 382; retired in 1939 – 394; General Counsel 359,381; Report to Temporary National Economic Committee – 397.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Young, Owen 1874 births 1962 deaths American lawyers American telecommunications industry businesspeople American diplomats Boston University School of Law alumni People from Herkimer County, New York American Unitarian Universalists General Electric people New York (state) Democrats St. Lawrence University alumni Time Person of the Year General Electric chief executive officers

Radio Corporation of America

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Com ...

. Young founded RCA as a subsidiary of General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable en ...

in 1919; he became its first chairman and continued in that position until 1929. RCA was divested in 1932 and liquidated by GE in 1986.

Early life and family

Owen D. Young was born on October 27, 1874 on a small farmhouse in the village of Van Hornesville, Town of Stark, New York. His parents’ names were Jacob Smith Young and Ida Brandow and they worked the farm that his grandfather owned. Owen was an only child, his parents lost their first born son before he was born, and his birth was something rejoiced. He was the first male of the family to have a name that was not biblical since they had first arrived in 1750, driven from the Palatinate on the Rhine inGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

by constant war and religious persecution. They were taken in by the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

Queen Anne in England, sent to New York in 1710 to act to provide naval stores for the British fleet along the Hudson River, and eventually moving north and west, taking land from the Native Americans before settling along the Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

* Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

* Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been ...

. The ‘D’ in his name was more for adornment than anything else, and so does not stand for anything.

Owen went to school for the first time in the spring of 1881. He was six years old, and had always been inclined to books and studying. He had a teacher, Menzo McEwan, who taught him for years, and would eventually be responsible for Owen going to East Springfield, one of the few secondary schools that he could afford. Of course, it was not too close to Van Hornesville, which had few secondary education opportunities near it. This took him away from the farm, where his help was needed, but his parents supported his pursuit of education to the point of later mortgaging the farm to send him to St. Lawrence University at Canton, New York

Canton is an incorporated Administrative divisions of New York#Town, town in St. Lawrence County, New York, St. Lawrence County, New York (state), New York. The population was 11,638 at the time of the 2020 census. The town contains two Administr ...

.

He married Josephine Sheldon Edmonds (1870–1935) on June 13, 1898 in Southbridge, Massachusetts

Southbridge is a city in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 17,740 at the 2020 census. Although Southbridge has a city form of government, it is legally known as the Town of Southbridge.

History

The area was in ...

. A few years after Josephine died, he married the fashion designer and businesswoman Louise Powis Clark (1887–1965), a widow with three children.

Children

* Charles Jacob Young (December 17, 1899 – October 2, 1987), Scientist and inventor at RCA * John Young (August 13, 1902 – August 21, 1926), (killed in a train accident) * Josephine Young (February 16, 1907 – January 8, 1990), who became a poet and novelist, writing as Josephine Young Case * Philip Young (May 9, 1910 – January 15, 1987), who becameDean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of the Columbia Business School (1948–1953), Chairman of the Civil Service Commission

A civil service commission is a government agency that is constituted by legislature to regulate the employment and working conditions of civil servants, oversee hiring and promotions, and promote the values of the public service. Its role is rough ...

(1953–1957), and United States Ambassador to the Netherlands

The United States diplomatic mission to the Netherlands consists of the embassy located in The Hague and a consular office located in Amsterdam.

In 1782, John Adams was appointed America's first Minister Plenipotentiary to Holland. According t ...

(1957–1960)

* Richard Young (June 23, 1919 – November 18, 2011), Attorney, expert on international

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

and maritime law, and law professor

Education

East Springfield Academy was a small coeducational school and Young greatly enjoyed his time there, making lifelong friends; later in life, he tried to attend all of the reunions. St. Lawrence was a small institute struggling to survive and in serious need of both money and students and Owen Young was a good candidate. It was still expensive enough to cause some hesitance, however. With his father getting on in years, Owen was needed on the farm more than ever. His parents were eventually convinced by the president of the college. It was there that Young was able to grow as a person in both his education and his faith. He discoveredUniversalism

Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is seen as more far-reaching th ...

, which allowed for more intellectual freedom, separate from the gloom and hellfire permeating other Christian sects. Young remained a student from September 1890 before becoming an 1894 graduate of St. Lawrence University, on June 27. He completed the three-year law course at Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with ...

in two years, graduating cum laude in 1896.

After graduation he joined lawyer Charles H. Tyler and ten years later became a partner in that Boston law firm. They were involved in litigation cases between major companies. During college, he not only became a brother of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity, but he also met his future wife Josephine Sheldon Edmonds, an 1886 Radcliffe graduate. He married her in 1898, and she eventually bore him five children.

Career

Young representedStone and Webster

Stone & Webster was an American engineering services company based in Stoughton, Massachusetts. It was founded as an electrical testing lab and consulting firm by electrical engineers Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster in 1889. In the early ...

in a successful case against GE around 1911 and through that case came to the attention of Charles A. Coffin, the first president of General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable en ...

. After the death of GE's General Counsel Hinsdill Parsons in April 1912, Coffin invited Young to become the company's Chief Counsel and Young moved to Schenectady

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Y ...

. He became GE's president in 1922 and then in the same year was appointed inaugural chairman, serving in that position until 1939. Under his guidance and teaming with president Gerard Swope

Gerard Swope (December 1, 1872 – November 20, 1957) was an American electronics businessman. He served as the president of General Electric Company between 1922 and 1940, and again from 1942 until 1945. During this time Swope expanded GE's produ ...

, GE shifted into the extensive manufacturing of home electrical appliances, establishing the company as a leader in this field and speeding the mass electrification of farms, factories and transportation systems within the US.

In 1919, at the request of the government, he created the

In 1919, at the request of the government, he created the Radio Corporation of America

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Com ...

(RCA) to combat the threat of English control over the world's radio communications against America's struggling radio industry. He became its augmentation chairman and served in that position until 1929, helping to establish America's lead in the burgeoning technology of radio, making RCA the largest radio company in the world. In 1928, he was appointed to the board of trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation under a major reorganization of that institution, serving on that board also up to 1939.

Young's participation in President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's Second Industrial Conference following World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

marked the beginning of his counseling of five U.S. presidents. In 1924, he coauthored the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

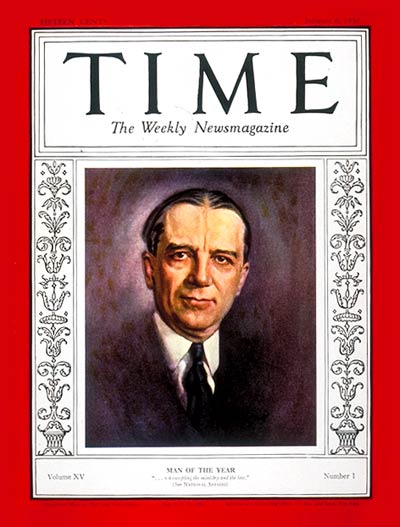

, which provided for a reduction in the annual amount of German reparations. In the late 1920s investments fell, and Germany again defaulted on its payments. In 1929 a new international body met to consider a program for the final release of German obligations; Young acted as chairman. Germany's total reparations were reduced and spread over 59 annual payments. After establishing this "Young Plan

The Young Plan was a program for settling Germany's World War I reparations. It was written in August 1929 and formally adopted in 1930. It was presented by the committee headed (1929–30) by American industrialist Owen D. Young, founder and for ...

", Young was named Time Magazine

''Time'' (stylized in all caps) is an American news magazine based in New York City. For nearly a century, it was published weekly, but starting in March 2020 it transitioned to every other week. It was first published in New York City on Ma ...

's Man of the Year in 1929. The Young Plan collapsed with the coming of the Great Depression.

Young was also instrumental in plans for a state university system in New York.

In 1932, he was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. He did not campaign actively, but his friends promoted his candidacy beginning in 1930 and at the 1932 Democratic National Convention. He was highly regarded by candidates Alfred E. Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, and some convention observers speculated that they would support Young in the event of a convention deadlock.

Retirement

In 1930, he built the Van Hornesville, New York, Central School in his hometown to consolidate all the small rural schools in the area. In 1963, it was renamed Owen D. Young Central School in his honor. Long active in education, Young was a trustee of St. Lawrence University from 1912 to 1934, serving as president of the board the last 10 years. The main library of the University is named in his honor. After Young married Louise Powis Clark in 1937, the couple created a winter estate in Florida that included a formal garden and citrus stand along State Road A1A. In 1965, Louise gifted the estate to the State of Florida, and it is now the site of Washington Oaks Gardens State Park. In 1939, he formally retired to the family farm in New York, where he began dairy farming. He died in Florida on July 11, 1962 following several months of poor health.Legacy

More than 20 colleges awarded him honorary degrees. Long interested in education, he was a member of theNew York State Board of Regents The Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York is responsible for the general supervision of all educational activities within New York State, presiding over University of the State of New York and the New York State Education Depa ...

, governing body of New York's educational system, until 1946. Then, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey called upon him to head the state commission that laid the groundwork for the State University of New York system. Although the commission represented a wide range of views and opinions, Young achieved a surprising unanimity that resulted in a report containing recommendations adopted by the legislature. He was inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 1981 and the Consumer Technology Hall of Fame in 2019.

See also

*List of Beta Theta Pi members

This is a list of notable members of Beta Theta Pi fraternity.

Academia

* List of Boston University School of Law alumni

* List of commencement speakers at Harvard University

* Community ...

List of covers of Time magazine (1920s)

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

/ (1930s)

* List of St. Lawrence University people

* List of Unitarians, Universalists, and Unitarian Universalists

*List of University of Florida honorary degree recipients

This list of University of Florida honorary degree recipients includes notable persons who have been recognized by the University of Florida for outstanding achievements in their fields that reflect the ideals and uphold the purposes of the unive ...

References and further reading

* Jones, Kenneth Paul, ed. ''U.S. Diplomats in Europe, 1919–41'' (ABC-CLIO. 1981online

on Young's role in Europe, pp 43–62.. * * * * Hammond, John Winthrop. ''Men and Volts, the Story of General Electric'', published 1941. Citations: came to Schenectady – 360; Chairman of the Board – 382; retired in 1939 – 394; General Counsel 359,381; Report to Temporary National Economic Committee – 397.

Notes

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Young, Owen 1874 births 1962 deaths American lawyers American telecommunications industry businesspeople American diplomats Boston University School of Law alumni People from Herkimer County, New York American Unitarian Universalists General Electric people New York (state) Democrats St. Lawrence University alumni Time Person of the Year General Electric chief executive officers