Outback on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of

The paucity of industrial land use has led to the Outback being recognised globally as one of the largest remaining intact natural areas on Earth. Global " Human Footprint" and wilderness reviews highlight the importance of Outback Australia as one of the world's large natural areas, along with the Boreal forests and Tundra regions in North America, the Sahara and Gobi deserts and the tropical forests of the Amazon and Congo Basins.

The savanna (or grassy woodlands) of northern Australia are the largest, intact savanna regions in the world. In the south, the Great Western Woodlands, which occupy , an area larger than all of England and Wales, are the largest remaining temperate woodland left on Earth.

The paucity of industrial land use has led to the Outback being recognised globally as one of the largest remaining intact natural areas on Earth. Global " Human Footprint" and wilderness reviews highlight the importance of Outback Australia as one of the world's large natural areas, along with the Boreal forests and Tundra regions in North America, the Sahara and Gobi deserts and the tropical forests of the Amazon and Congo Basins.

The savanna (or grassy woodlands) of northern Australia are the largest, intact savanna regions in the world. In the south, the Great Western Woodlands, which occupy , an area larger than all of England and Wales, are the largest remaining temperate woodland left on Earth.

The largest industry across the Outback, in terms of the area occupied, is pastoralism, in which cattle, sheep, and sometimes goats are grazed in mostly intact, natural ecosystems. Widespread use of bore water, obtained from underground aquifers, including the Great Artesian Basin, has enabled livestock to be grazed across vast areas in which no permanent surface water exists naturally.

Capitalising on the lack of pasture improvement and absence of fertiliser and pesticide use, many Outback pastoral properties are certified as organic livestock producers. In 2014, , most of which is in Outback Australia, was fully certified as organic farm production, making Australia the largest certified organic production area in the world.

The largest industry across the Outback, in terms of the area occupied, is pastoralism, in which cattle, sheep, and sometimes goats are grazed in mostly intact, natural ecosystems. Widespread use of bore water, obtained from underground aquifers, including the Great Artesian Basin, has enabled livestock to be grazed across vast areas in which no permanent surface water exists naturally.

Capitalising on the lack of pasture improvement and absence of fertiliser and pesticide use, many Outback pastoral properties are certified as organic livestock producers. In 2014, , most of which is in Outback Australia, was fully certified as organic farm production, making Australia the largest certified organic production area in the world.

The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) started service in 1928 and helps people who live in the outback of Australia. Previously, serious injuries or illnesses often meant death owing to the lack of proper medical facilities and trained personnel.

In many outback communities, the number of children is too small for a conventional school to operate. Children are educated at home by the School of the Air. Originally the teachers communicated with the children via radio, but now satellite telecommunication is used instead.

Some children attend boarding school, mostly only those in secondary school.

The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) started service in 1928 and helps people who live in the outback of Australia. Previously, serious injuries or illnesses often meant death owing to the lack of proper medical facilities and trained personnel.

In many outback communities, the number of children is too small for a conventional school to operate. Children are educated at home by the School of the Air. Originally the teachers communicated with the children via radio, but now satellite telecommunication is used instead.

Some children attend boarding school, mostly only those in secondary school.

The outback is criss-crossed by historic tracks. Most of the major highways have an excellent

The outback is criss-crossed by historic tracks. Most of the major highways have an excellent

From this Broken HillBeautiful Australian Outback

– slideshow by '' Life magazine''

Audio slideshow: Outback Australia – The royal flying doctor service

Carl Bridge, head of the Menzies Centre for Australian studies at KCL, outlines the history of the Royal Flying Doctor Service. ''The Royal Geography Society's Hidden Journeys project'' {{Authority control Rural geography Regions of Australia Deserts of Australia Australian outback Australian slang Culture of Australia Rural culture in Oceania Northern Australia

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. The Outback is more remote than the bush. While often envisaged as being arid, the Outback regions extend from the northern to southern Australian coastlines and encompass a number of climatic zones, including tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

and monsoonal climates in northern areas, arid areas in the "red centre" and semi-arid and temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

climates in southerly regions. The total population is estimated at 607,000 people.

Geographically, the Outback is unified by a combination of factors, most notably a low human population density, a largely intact natural environment

The natural environment or natural world encompasses all life, biotic and abiotic component, abiotic things occurring nature, naturally, meaning in this case not artificiality, artificial. The term is most often applied to Earth or some parts ...

and, in many places, low-intensity land uses, such as pastoralism (livestock grazing) in which production is reliant on the natural environment. The Outback is deeply ingrained in Australian heritage, history and folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

. In Australian art the subject of the Outback has been vogue, particularly in the 1940s. In 2009, as part of the Q150 celebrations, the Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

Outback was announced as one of the Q150 Icons of Queensland for its role as a "natural attraction".

History

Aboriginal peoples have lived in the Outback for at least 50,000 years and occupied all Outback regions, including the driest deserts, when Europeans first entered central Australia in the 1800s. Many Aboriginal Australians retain strong physical and cultural links to their traditional country and are legally recognised as the Traditional Owners of large parts of the Outback under Commonwealth Native Title legislation. Early European exploration of inland Australia was sporadic. More focus was on the more accessible and fertile coastal areas. The first party to successfully cross the Blue Mountains just outsideSydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

was led by Gregory Blaxland in 1813, 25 years after the colony was established. People, starting with John Oxley

John Joseph William Molesworth Oxley (1784 – 25 May 1828) was an English List of explorers, explorer and surveyor of Australia in the early period of British colonisation. He served as Surveyor General of New South Wales and is perhaps bes ...

in 1817, 1818 and 1821, followed by Charles Sturt from 1829 to 1830, attempted to follow the westward-flowing rivers to find an "inland sea", but these were found to all flow into the Murray River and Darling River, which turn south.

From 1858 onwards, the so-called "Afghan" cameleers and their beasts played an instrumental role in opening up the Outback and helping to build infrastructure.

Over the period 1858 to 1861, John McDouall Stuart led six expeditions north from Adelaide, South Australia into the Outback, culminating in successfully reaching the north coast of Australia and returning without the loss of any of the party's members' lives. This contrasts with the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition in 1860–61 which was much better funded, but resulted in the deaths of three of the members of the transcontinental party.

The Overland Telegraph line was constructed in the 1870s along the route identified by Stuart.

In 1865, the surveyor George Goyder, using changes in vegetation patterns, mapped a line in South Australia, north of which he considered rainfall to be too unreliable to support agriculture.

Exploration of the Outback continued in the 1950s when Len Beadell explored, surveyed and built many roads in support of the nuclear weapons tests at Emu Field and Maralinga and rocket testing on the Woomera Prohibited Area. Mineral exploration continues as new mineral deposits are identified and developed.

2002 was declared the Year of the Outback. While the early explorers used horses to cross the Outback, the first woman to make the journey riding a horse was Anna Hingley, who rode from Broome to Cairns in 2006.

Environment

Global significance

Major ecosystems

Reflecting the wide climatic and geological variation, the Outback contains a wealth of distinctive and ecologically rich ecosystems. Major land types include: * the Kimberley and Pilbara regions in northern Western Australia, * sub-tropical savanna landscape of the Top End, * ephemeral water courses of the Channel Country in western Queensland, * the ten deserts in central and western Australia, * the Inland Ranges, such as the MacDonnell Ranges, which provide topographic variation across the flat plains, * the flat Nullarbor Plain north of the Great Australian Bight, and * the Great Western Woodlands in southern Western Australia.Wildlife

The Outback is full of very important well-adapted wildlife, although much of it may not be immediately visible to the casual observer. Many animals, such as red kangaroos and dingoes, hide in bushes to rest and keep cool during the heat of the day. Birdlife is prolific, most often seen at waterholes at dawn and dusk. Huge flocks of budgerigars, cockatoos, corellas and galahs are often sighted. On bare ground or roads during the winter, various species of snakes and lizards bask in the sun, but they are rarely seen during the summer months. Feral animals such as camels thrive in central Australia, brought to Australia by pastoralists and explorers, along with the early Afghan drivers. Feral horses known as ' brumbies' are station horses that have run wild. Feral pigs, foxes, cats, goats and rabbits and other imported animals are also degrading the environment, so time and money is spent eradicating them in an attempt to help protect fragile rangelands. The Outback is home to a diverse set of animal species, such as the kangaroo, emu and dingo. The Dingo Fence was built to restrict movements of dingoes and wild dogs into agricultural areas towards the south east of the continent. The marginally fertile parts are primarily utilised as rangelands and have been traditionally used for sheep or cattle grazing, on cattle stations which are leased from the Federal Government. While small areas of the outback consist of clay soils the majority has exceedingly infertile palaeosols. Riversleigh, in Queensland, is one of Australia's most renowned fossil sites and was recorded as a World Heritage site in 1994. The area contains fossil remains of ancient mammals, birds and reptiles ofOligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

and Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

age.

Industry

Pastoralism

The largest industry across the Outback, in terms of the area occupied, is pastoralism, in which cattle, sheep, and sometimes goats are grazed in mostly intact, natural ecosystems. Widespread use of bore water, obtained from underground aquifers, including the Great Artesian Basin, has enabled livestock to be grazed across vast areas in which no permanent surface water exists naturally.

Capitalising on the lack of pasture improvement and absence of fertiliser and pesticide use, many Outback pastoral properties are certified as organic livestock producers. In 2014, , most of which is in Outback Australia, was fully certified as organic farm production, making Australia the largest certified organic production area in the world.

The largest industry across the Outback, in terms of the area occupied, is pastoralism, in which cattle, sheep, and sometimes goats are grazed in mostly intact, natural ecosystems. Widespread use of bore water, obtained from underground aquifers, including the Great Artesian Basin, has enabled livestock to be grazed across vast areas in which no permanent surface water exists naturally.

Capitalising on the lack of pasture improvement and absence of fertiliser and pesticide use, many Outback pastoral properties are certified as organic livestock producers. In 2014, , most of which is in Outback Australia, was fully certified as organic farm production, making Australia the largest certified organic production area in the world.

Tourism

Tourism is a major industry across the Outback, and commonwealth and state tourism agencies explicitly target Outback Australia as a desirable destination for domestic and international travellers. There is no breakdown of tourism revenues for the "Outback" ''per se''. However, regional tourism is a major component of national tourism incomes. Tourism Australia explicitly markets nature-based and Indigenous-led experiences to tourists. In the 2015–2016 financial year, 815,000 visitors spent $988 million while on holidays in the Northern Territory alone. There are many popular tourist attractions in the Outback. Some of the well known destinations include Devils Marbles, Kakadu National Park, Kata Tjuta (The Olgas), MacDonnell Ranges and Uluru (Ayers Rock).Mining

Other than agriculture and tourism, the main economic activity in this vast and sparsely settled area is mining. Owing to the almost complete absence of mountain building and glaciation since thePermian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

(in many areas since the Cambrian) ages, the outback is extremely rich in iron, aluminium, manganese and uranium ores, and also contains major deposits of gold, nickel, copper, lead and zinc ores. Because of its size, the value of grazing and mining is considerable. Major mines and mining areas in the Outback include opals at Coober Pedy, Lightning Ridge and White Cliffs, metals at Broken Hill, Tennant Creek, Olympic Dam and the remote Challenger Mine. Oil and gas are extracted in the Cooper Basin around Moomba.

In Western Australia the Argyle diamond mine in the Kimberley was once the world's biggest producer of natural diamonds and contributed approximately one-third of the world's natural supply, but was closed down in 2020 due to financial reasons. The Pilbara region's economy is dominated by mining and petroleum industries. The Pilbara's oil and gas industry is the region's largest export industry, earning $5.0 billion in 2004/05 and accounting for over 96% of the State's production. Most of Australia's iron ore is also mined in the Pilbara and it also has one of the world's major manganese mines.

Population

Aboriginal communities in outback regions, such as the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands in northern South Australia, have not been displaced as they have been in areas of intensive agriculture and large cities, in coastal areas. The total population of the Outback in Australia declined from 700,000 in 1996 to 690,000 in 2006. The largest decline was in the Outback Northern Territory, while the Kimberley and Pilbara showed population increases during the same period. The sex ratio is 1040 males for 1000 females and 17% of the total population is indigenous.Facilities

The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) started service in 1928 and helps people who live in the outback of Australia. Previously, serious injuries or illnesses often meant death owing to the lack of proper medical facilities and trained personnel.

In many outback communities, the number of children is too small for a conventional school to operate. Children are educated at home by the School of the Air. Originally the teachers communicated with the children via radio, but now satellite telecommunication is used instead.

Some children attend boarding school, mostly only those in secondary school.

The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) started service in 1928 and helps people who live in the outback of Australia. Previously, serious injuries or illnesses often meant death owing to the lack of proper medical facilities and trained personnel.

In many outback communities, the number of children is too small for a conventional school to operate. Children are educated at home by the School of the Air. Originally the teachers communicated with the children via radio, but now satellite telecommunication is used instead.

Some children attend boarding school, mostly only those in secondary school.

Terminology

The term "outback" derives from the adverbial phrase referring to the backyard of a house, and came to be used meiotically in the late 1800s to describe the vast sparsely settled regions of Australia behind the cities and towns. The earliest known use of the term in this context in print was in 1869, when the writer clearly meant the area west of Wagga Wagga,New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

.Coupe, Sheena (ed.), Frontier Country, Vol. 1, Weldon Russell Publishing, Willoughby, 1989, Over time, the adverbial use of the phrase was replaced with the present day noun form.

It is colloquially said that "the outback" is located "beyond the Black Stump". The location of the black stump may be some hypothetical location or may vary depending on local custom and folklore. It has been suggested that the term comes from the Black Stump Wine Saloon that once stood about out of Coolah, New South Wales on the Gunnedah Road. It is claimed that the saloon, named after the nearby Black Stump Run and Black Stump Creek, was an important staging post for traffic to north-west New South Wales and it became a marker by which people gauged their journeys.

"The Never-Never" is a term referring to remoter parts of the Outback. The Outback can also be referred to as "back of beyond" or "back o' Bourke", although these terms are more frequently used when referring to something a long way from anywhere, or a long way away. The well-watered north of the continent is often called the " Top End" and the arid interior "The Red Centre", owing to its vast amounts of red soil and sparse greenery amongst its landscape.

Transport

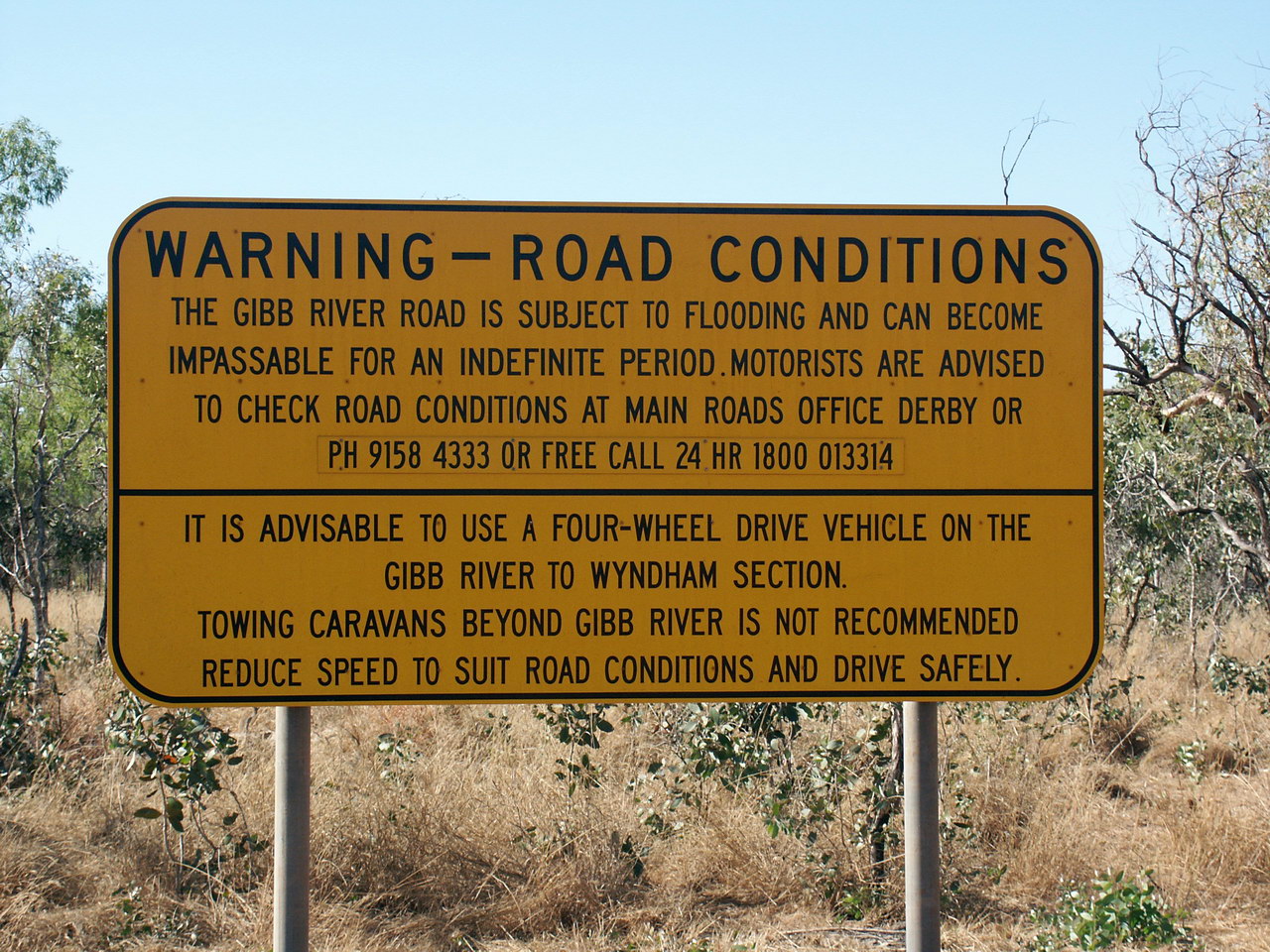

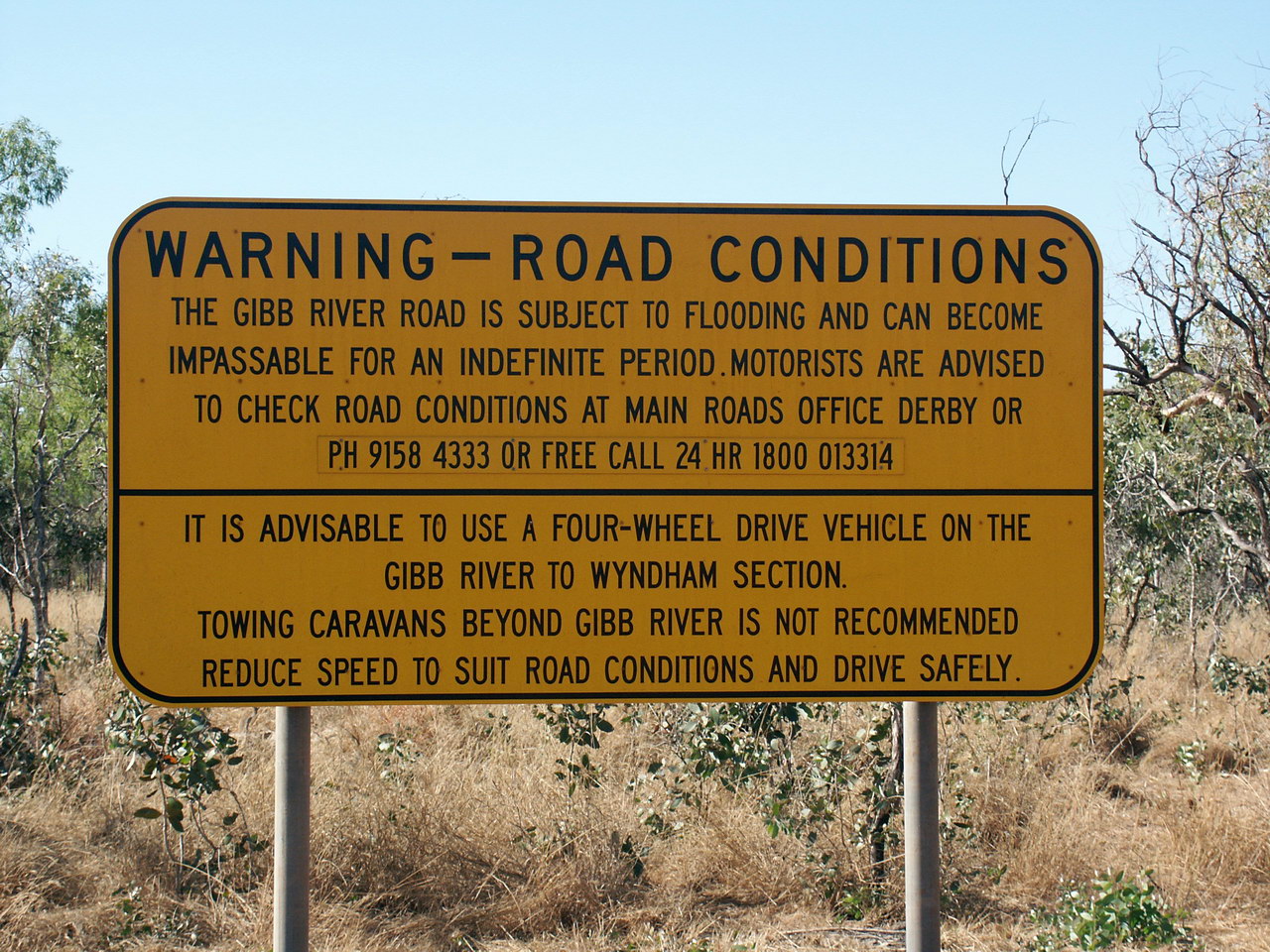

The outback is criss-crossed by historic tracks. Most of the major highways have an excellent

The outback is criss-crossed by historic tracks. Most of the major highways have an excellent bitumen

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscosity, viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American Engl ...

surface and other major roads are usually well-maintained dirt roads.

The Stuart Highway runs from north to south through the centre of the continent, roughly paralleled by the Adelaide–Darwin railway. There is a proposal to develop some of the roads running from the south-west to the north-east to create an all-weather road named the Outback Highway, crossing the continent diagonally from Laverton, Western Australia (north of Kalgoorlie, through the Northern Territory to Winton, in Queensland.

Air transport is relied on for mail delivery in some areas, owing to sparse settlement and wet-season road closures. Most outback mines have an airstrip and many have a fly-in fly-out workforce. Most outback sheep stations and cattle stations have an airstrip and quite a few have their own light plane. Medical and ambulance services are provided by the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

See also

* Australian landmarks * Bushland *Central Australia

Central Australia, also sometimes referred to as the Red Centre, is an inexactly defined region associated with the geographic centre of Australia. In its narrowest sense it describes a region that is limited to the town of Alice Springs and ...

* Channel Country

* Australian outback literature of the 20th century

* Australian desert

Notes

References

Further reading

* Dwyer, Andrew (2007). ''Outback – Recipes and Stories from the Campfire'' Miegunyah Press * Read, Ian G. (1995). ''Australia's central and western outback : the driving guide'' Crows Nest, N.S.W. Little Hills Press. Little Hills Press explorer guides * ''Year of the Outback 2002'', Western Australia Perth, W.A.External links

From this Broken Hill

– slideshow by '' Life magazine''

Audio slideshow: Outback Australia – The royal flying doctor service

Carl Bridge, head of the Menzies Centre for Australian studies at KCL, outlines the history of the Royal Flying Doctor Service. ''The Royal Geography Society's Hidden Journeys project'' {{Authority control Rural geography Regions of Australia Deserts of Australia Australian outback Australian slang Culture of Australia Rural culture in Oceania Northern Australia