Osage (tribe) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Osage Nation ( ) ( Osage: 𐓁𐒻 𐓂𐒼𐒰𐓇𐒼𐒰͘ ('), "People of the Middle Waters") is a

Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1995, pp. 96-100 Some believe that the Osage started migrating west as early as 1200 CE and are descendants of the Mississippian culture in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. They attribute their style of government to effects of the long years of war with invading Iroquois. After resettling west of the Mississippi River, the Osage were sometimes allied with the

"Osage"

''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'', retrieved 2 March 2009 Eventually the Osage and other Dhegihan-Siouan peoples reached their historic lands, likely developing and splitting into the above tribes in the course of the migration to the Great Plains. By the 17th century, many of the Osage had settled near the

The Osage called the Europeans ' (Heavy Eyebrows) because of their facial hair. As experienced warriors, the Osage allied with the French, with whom they traded, against the Illiniwek during the early 18th century. The first half of the 1720s was a time of more interaction between the Osage and French colonizers. Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont founded Fort Orleans in their territory; it was the first European colonial fort on the Missouri River. Jesuit missionaries were assigned to French forts and established missions in an attempt to convert the Osage, learning their language to ingratiate themselves. In 1724, the Osage allied with the French rather than the Spanish in their fight for control of the Mississippi region. In 1725, Bourgmont led a delegation of Osage and other tribal chiefs to

The Osage called the Europeans ' (Heavy Eyebrows) because of their facial hair. As experienced warriors, the Osage allied with the French, with whom they traded, against the Illiniwek during the early 18th century. The first half of the 1720s was a time of more interaction between the Osage and French colonizers. Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont founded Fort Orleans in their territory; it was the first European colonial fort on the Missouri River. Jesuit missionaries were assigned to French forts and established missions in an attempt to convert the Osage, learning their language to ingratiate themselves. In 1724, the Osage allied with the French rather than the Spanish in their fight for control of the Mississippi region. In 1725, Bourgmont led a delegation of Osage and other tribal chiefs to  In 1804 after the United States made the

In 1804 after the United States made the

The Choctaw chief

The Choctaw chief

''The Arkansas Historical Quarterly'', Vol. 64, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), accessed 8 April 2014 Cultural differences often led to conflicts, as the Protestants tried to impose their culture. The Catholic Church also sent missionaries. The Osage were attracted to their sense of mystery and ritual but felt the Catholics did not fully embrace the Osage sense of the spiritual incarnate in nature. During this period in Kansas, the tribe suffered from the widespread

University of Alabama Press, 1989/2004, pp. 226-227 and pp. 229-230 During a 35-year period, most of the missionaries were new recruits from Europe: Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. They taught, established more than 100 mission stations, built churches, and created the longest-running school system in Kansas.

The Osage were one of the few American Indian nations to buy their own reservation. As a result, they retained more rights to the land and sovereignty. They retained mineral rights on their lands. Dennis McAuliffe (1994), ''The Deaths of Sybil Bolton: An American History,'' Times Books; republished a

The Osage were one of the few American Indian nations to buy their own reservation. As a result, they retained more rights to the land and sovereignty. They retained mineral rights on their lands. Dennis McAuliffe (1994), ''The Deaths of Sybil Bolton: An American History,'' Times Books; republished a

(1994), ''Bloodland: A Family Story of Oil, Greed and Murder on the Osage Reservation''

Council Oak Books The reservation, of approximately , is coterminous with present-day

The Osage had learned about negotiating with the U.S. government. Through the efforts of Principal Chief James Bigheart, in 1907 they reached a deal which enabled them to retain communal mineral rights on the reservation lands. These were later found to have large quantities of crude oil, and tribal members benefited from royalty revenues from oil development and production. The government leased lands on their behalf for oil development; the companies/government sent the Osage members royalties that, by the 1920s, had dramatically increased their wealth. In 1923 alone, the Osage earned $30 million in royalties. Since the early 20th century, they are the only tribe within the state of Oklahoma to retain a federally recognized reservation.2011 "Osage Reservation"

The Osage had learned about negotiating with the U.S. government. Through the efforts of Principal Chief James Bigheart, in 1907 they reached a deal which enabled them to retain communal mineral rights on the reservation lands. These were later found to have large quantities of crude oil, and tribal members benefited from royalty revenues from oil development and production. The government leased lands on their behalf for oil development; the companies/government sent the Osage members royalties that, by the 1920s, had dramatically increased their wealth. In 1923 alone, the Osage earned $30 million in royalties. Since the early 20th century, they are the only tribe within the state of Oklahoma to retain a federally recognized reservation.2011 "Osage Reservation"

, ''Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory,'' Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission, 2011: 24. Retrieved 24 Jan 2012 In 2000 the Osage sued the federal government over its management of the trust assets, alleging that it had failed to pay tribal members appropriate royalties, and had not historically protected the land assets and appreciation. The suit was settled in 2011 for $380 million, and a commitment by the government to make numerous changes to improve the program. In 2016, the Osage nation bought

The Osage Tribal Council was created under the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. It consisted of a principal chief, an assistant principal chief, and eight members of the Osage tribal council. The mineral estate consists of more than natural gas and petroleum. Although these two resources have yielded the most profit, the Osage have also earned revenue from leases for the mining of lead, zinc, limestone, and coal deposits. Water may also be considered a profitable asset that is controlled by the Mineral Council.

The first elections for this council were held in 1908 on the first Monday in June. Officers were elected for a term of two years, which made it difficult for them to accomplish long-term goals. If for some reason the principal chief's office becomes vacant, a replacement is elected by the remaining council members. Later in the 20th century, the tribe increased the terms of office of council members to four years. In 1994 by referendum, the tribe voted for a new constitution; among its provisions was the separation of the Mineral Council, or Mineral Estate, from regular tribal government. According to the constitution, only Osage members who are also headright holders can vote for the members of the Mineral Council. It is as if they were shareholders of a corporation.

The Osage Tribal Council was created under the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. It consisted of a principal chief, an assistant principal chief, and eight members of the Osage tribal council. The mineral estate consists of more than natural gas and petroleum. Although these two resources have yielded the most profit, the Osage have also earned revenue from leases for the mining of lead, zinc, limestone, and coal deposits. Water may also be considered a profitable asset that is controlled by the Mineral Council.

The first elections for this council were held in 1908 on the first Monday in June. Officers were elected for a term of two years, which made it difficult for them to accomplish long-term goals. If for some reason the principal chief's office becomes vacant, a replacement is elected by the remaining council members. Later in the 20th century, the tribe increased the terms of office of council members to four years. In 1994 by referendum, the tribe voted for a new constitution; among its provisions was the separation of the Mineral Council, or Mineral Estate, from regular tribal government. According to the constitution, only Osage members who are also headright holders can vote for the members of the Mineral Council. It is as if they were shareholders of a corporation.

"Osage Government Reform"

Arizona Native Net

, 2006. Retrieved on 2009-10-05. From 2004 to 2006, the Osage Government Reform Commission formed and worked to develop a new government. It explored "sharply differing visions arose of the new government's goals, the nation's own history, and what it means to be Osage. The primary debates were focused on biology, culture, natural resources, and sovereignty."Jean Dennison, ''Colonial Entanglement: Constituting a Twenty-First-Century Osage Nation''

UNC Press Books, 2012, Introduction The Reform Commission held weekly meetings to develop a referendum that Osage members could vote upon in order to develop and reshape the Osage Nation government and its policies. On March 11, 2006, the people ratified the constitution in a second referendum vote. Its major provision was to provide "

The Osage Nation, News, May 2016; accessed 1 July 2017 By a 2/3 majority vote, the Osage Nation adopted the new constitutional form of government. It also ratified the definition of membership in the nation. Today, the Osage Nation has 13,307 enrolled tribal members, with 6,747 living within the state of Oklahoma. Since 2006 it has defined membership based on a person's lineal descent from a member listed on the Osage rolls at the time of the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. A minimum blood quantum is not required. But, as the Bureau of Indian Affairs restricts federal education scholarships to persons who have 25% or more blood quantum in one tribe, the Osage Nation tries to support higher education for its students who do not meet that requirement. The tribal government is headquartered in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, and has jurisdiction in Osage County, Oklahoma. The current governing body of the Osage nation contains three separate branches; an executive, a judicial and a legislative. These three branches parallel the United States government in many ways. The tribe operates a monthly newspaper, ''Osage News.'' The Osage Nation has an official website and uses a variety of communication media and technology.

* Fred Lookout (1865-1949), principal chief

* Monte Blue (1887–1963), American actor of the silent and

* Fred Lookout (1865-1949), principal chief

* Monte Blue (1887–1963), American actor of the silent and

"Osage actor stars in cable TV movie this year."

''Osage News.'' 7 March 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2013. * Jerry C. Elliott (b. 1943), one of the first Native Americans in

, ''Osage News,'' 27 August 2010 *

Osage Nation

official website

from ''Handbook of North American Indian History'', Smithsonian Institution, 1906, at Access Genealogy

Midwestern

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

Native American tribe of the Great Plains. The tribe developed in the Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

river valleys around 700 BC along with other groups of its language family. They migrated west after the 17th century, settling near the confluence of the Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

and Mississippi rivers, as a result of Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

invading the Ohio Valley in a search for new hunting grounds.

The term "Osage" is a French version of the tribe's name, which can be roughly translated as "calm water". The Osage people refer to themselves in their indigenous Dhegihan

The Dhegihan languages are a group of Siouan languages that include Kansa– Osage, Omaha–Ponca, and Quapaw. Their historical region included parts of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, the Great Plains, and southeastern North America. T ...

Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the enti ...

language as 𐓏𐒰𐓓𐒰𐓓𐒷 ('), or "Mid-waters".

By the early 19th century, the Osage had become the dominant power in the region, feared by neighboring tribes. The tribe controlled the area between the Missouri and Red

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–740 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondar ...

rivers, the Ozarks

The Ozarks, also known as the Ozark Mountains, Ozark Highlands or Ozark Plateau, is a physiographic region in the U.S. states of Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and the extreme southeastern corner of Kansas. The Ozarks cover a significant port ...

to the east and the foothills of the Wichita Mountains

The Wichita Mountains are located in the southwestern portion of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the principal relief system in the Southern Oklahoma Aulacogen, being the result of a failed continental rift. The mountains are a northwest-south ...

to the south. They depended on nomadic buffalo hunting and agriculture.

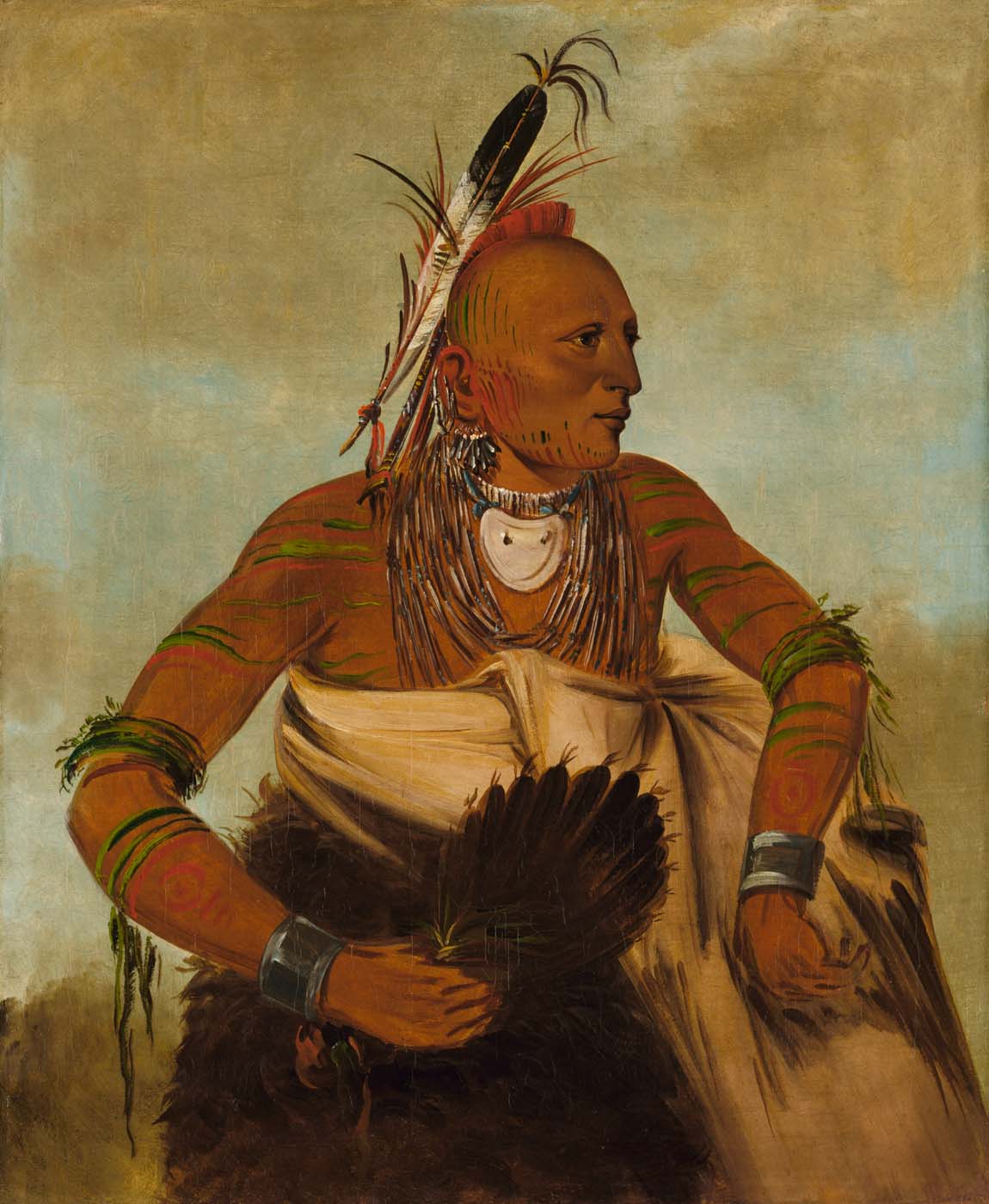

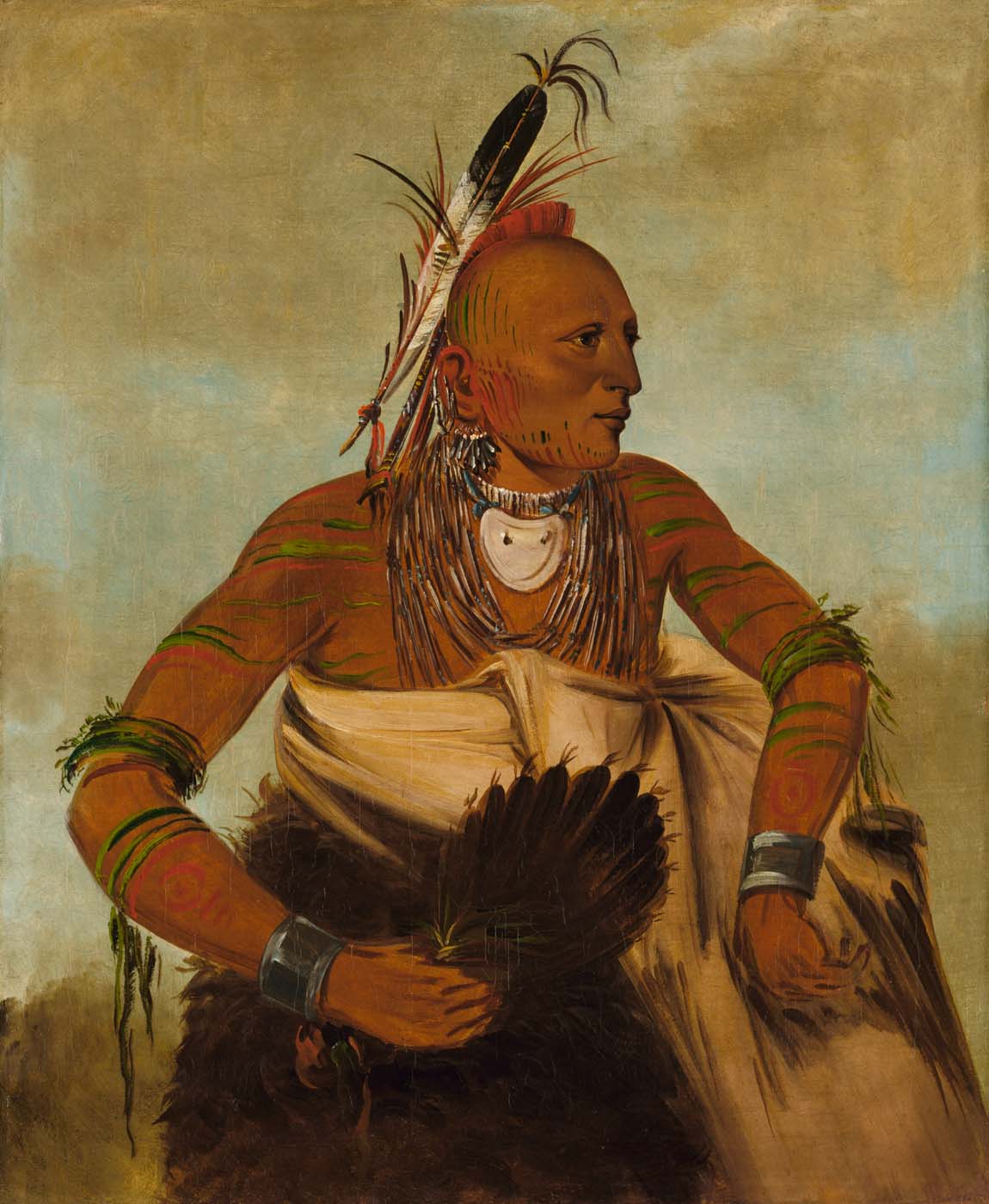

The 19th-century painter George Catlin

George Catlin (July 26, 1796 – December 23, 1872) was an American adventurer, lawyer, painter, author, and traveler, who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the Old West.

Traveling to the American West five times during the 183 ...

described the Osage as "the tallest race of men in North America, either red or white skins; there being ... many of them six and a half, and others seven feet." The missionary Isaac McCoy

Isaac McCoy (June 13, 1784 – June 21, 1846) was a Baptist missionary among the Native Americans in what is now Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, and Kansas. He was an advocate of Indian removal from the eastern United States, proposing an Indian ...

described the Osage as an "uncommonly fierce, courageous, warlike nation" and said they were the "finest looking Indians I have ever seen in the West".

In the Ohio Valley, the Osage originally lived among speakers of the same Dhegihan language stock, such as the Kansa, Ponca

The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...

, Omaha, and Quapaw

The Quapaw ( ; or Arkansas and Ugahxpa) people are a tribe of Native Americans that coalesced in what is known as the Midwest and Ohio Valley of the present-day United States. The Dhegiha Siouan-speaking tribe historically migrated from the Oh ...

. Researchers believe that the tribes likely became differentiated in languages and cultures after leaving the lower Ohio country. The Omaha and Ponca settled in what is now Nebraska; the Kansa in Kansas; and the Quapaw in Arkansas.

In the 19th century, the Osage were forced by the United States to remove from Kansas to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(present-day Oklahoma), and the majority of their descendants live in Oklahoma. In the early 20th century, oil was discovered on their land. They had retained communal mineral rights during the allotment process, and many Osage became wealthy through returns from leasing fees generated by their headright A headright refers to a legal grant of land given to settlers during the period of European colonization in the Americas. Headrights are most notable for their role in the expansion of the Thirteen Colonies; the Virginia Company gave headrights to s ...

s. However, during the 1920s and what was known as the Reign of Terror, they suffered manipulation, fraud, and numerous murders by outsiders eager to take over their wealth.

In 2011, the nation gained a settlement from the federal government after an 11-year legal struggle over long mismanagement of their oil funds. In the 21st century, the federally recognized Osage Nation has approximately 20,000 enrolled members, 6,780 of whom reside in the tribe's jurisdictional area. Members also live outside the nation's tribal land in Oklahoma and in other states around the country. The tribe is bordered by the Cherokee Nation to the east, the Muscogee Nation and the Pawnee Nation to the south, and the Kaw Nation

The Kaw Nation (or Kanza or Kansa) is a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma and parts of Kansas. It comes from the central Midwestern United States. It has also been called the "People of the South wind",

and Oklahoma proper to the west.

History

Traditional spirituality

Osage people believed they were an integral part of a broader universe. Their ceremonies and social organization represented what was observed around them that was created by Wakonda. Everything created has the spirit of Wakonda within it, from trees, plants, and the sky to animals and human beings. They believed there were two main divisions to life, consisting of the sky and earth. Life is created in the sky, and descends to the earth in material form. The sky was viewed as masculine in nature and the earth as feminine. They revered the behavior of animals such as hawks, deer and bears, which were considered to be very courageous. Other species lived long lives, such as pelicans. Because humans lacked many of the characteristics naturally found within other forms of life around them, they were expected to learn from the others and emulate characteristics desirable for survival. Survival was not a competition between humans and non-humans, but rather a struggle between human communities. Efforts for survival were the responsibility of the people and not of Wakonda, although they might ask Wakonda for help. Considering life a struggle among human groups, they viewed warfare as necessary for self-preservation. The people's survival was dependent on their ability to defend themselves. Over time, the Osage developed clan andkinship system

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

s that mirrored the cosmos as they saw it. Osage clans were typically named after elements of their world: animals, plants and weather phenomenon such as storms.

This was a symbolic representation. Each clan had its own responsibilities within the tribe. Names of clans included Red Cedar (''Hon-tse-shu-tsy''), Travelers in the Mist (''Moh-sho-tsa-moie''), Deer Lungs (''Tah-lah-he'') and Elk (''O-pon''). Children born to a certain clan had a ceremonial naming in order to introduce them to the community. Without a ceremonial name, an Osage child could not participate in ceremonies, so naming was an important part of Osage identity. The people regulated marriage through the clans: clan members had to marry people from opposite clans or divisions. Clan representation was expressed in the arrangement of Osage villages. The sky people lived on the side opposite the earth people, and the lodges of the Osage spiritual leaders were situated in between the two sides.

Osage life was highly ritualized, where there were certain ceremonies would be performed utilizing bundles, ceremonial pipes which used tobacco as offerings to seek Wakonda's aid. These ceremonies were presided over by Osage medicine people and spiritual leaders. Although some of the literature cites these individuals as "priests", this term is misleading and is more Eurocentric in nature. Ceremonies, although very elaborate served basic functions such as requesting aid from Wakonda for continued tribal existence and the blessing of a long life through children.

Ceremonial songs were also a way to document the knowledge spiritual leaders gained, considering there was no written language. Songs of this nature were only taught and shared among other Osages who were sincere and had proven themselves. Many songs and ceremonies were created for all facets of life such as adoption, marriage, war, agriculture and to honor the rising of the sun in the morning.

Pre-colonization

The Osage are descendants of cultures of indigenous peoples who had been in North America for thousands of years. Studies of their traditions and language show that they were part of a group of Dhegihan-Siouan speaking people who lived in the Ohio River valley area, extending into present-dayKentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

. According to their own stories (common to other Dhegihan-Siouan tribes, such as the Ponca, Omaha, Kaw and Quapaw), they migrated west as a result of war with the Iroquois and/or to reach more game.

Scholars are divided as to whether they think the Osage and other groups left before the Beaver Wars of the Iroquois.Willard H. Rollins, ''The Osage: An Ethnohistorical Study of Hegemony on the Prairie-Plains''Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1995, pp. 96-100 Some believe that the Osage started migrating west as early as 1200 CE and are descendants of the Mississippian culture in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. They attribute their style of government to effects of the long years of war with invading Iroquois. After resettling west of the Mississippi River, the Osage were sometimes allied with the

Illiniwek

The Illinois Confederation, also referred to as the Illiniwek or Illini, were made up of 12 to 13 tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley. Eventually member tribes occupied an area reaching from Lake Michicigao (Michigan) to Iowa, Ill ...

and sometimes competed with them, as that tribe was also driven west of Illinois by warfare with the powerful Iroquois.Louis F. Burns"Osage"

''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'', retrieved 2 March 2009 Eventually the Osage and other Dhegihan-Siouan peoples reached their historic lands, likely developing and splitting into the above tribes in the course of the migration to the Great Plains. By the 17th century, many of the Osage had settled near the

Osage River

The Osage River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed May 31, 2011 tributary of the Missouri River in central Missouri in the United States. The eighth-largest river ...

in the western part of present-day Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

. They were recorded in 1690 as having adopted the horse (a valuable resource often acquired through raids on other tribes.) The desire to acquire more horses contributed to their trading with the French. They attacked and defeated indigenous Caddo tribes to establish dominance in the Plains region by 1750, with control "over half or more of Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Kansas," which they maintained for nearly 150 years. Together with the Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

, Comanche, and Apache, they dominated western Oklahoma.

The Osage held high rank among the old hunting tribes of the Great Plains. From their traditional homes in the woodlands of present-day Missouri and Arkansas, the Osage would make semi-annual buffalo hunting forays into the Great Plains to the west. They also hunted deer, rabbit, and other wild game in the central and eastern parts of their domain. The women cultivated varieties of corn, squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

, and other vegetables near their villages, which they processed for food. They also harvested and processed nuts and wild berries. In their years of transition, the Osage had cultural practices that had elements of the cultures of both Woodland Native Americans and the Great Plains peoples. The villages of the Osage were important hubs in the Great Plains trading network served by Kaw people as intermediaries.

Early French colonization

In 1673, French explorersJacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

and Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore and ...

were among the first Europeans documented to contact the Osage, traveling southward from present-day Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

in their journey along the Mississippi River. Marquette's 1673 map noted the Kanza, Osage, and Pawnee tribes thrived in much of modern-day Kansas.

The Osage called the Europeans ' (Heavy Eyebrows) because of their facial hair. As experienced warriors, the Osage allied with the French, with whom they traded, against the Illiniwek during the early 18th century. The first half of the 1720s was a time of more interaction between the Osage and French colonizers. Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont founded Fort Orleans in their territory; it was the first European colonial fort on the Missouri River. Jesuit missionaries were assigned to French forts and established missions in an attempt to convert the Osage, learning their language to ingratiate themselves. In 1724, the Osage allied with the French rather than the Spanish in their fight for control of the Mississippi region. In 1725, Bourgmont led a delegation of Osage and other tribal chiefs to

The Osage called the Europeans ' (Heavy Eyebrows) because of their facial hair. As experienced warriors, the Osage allied with the French, with whom they traded, against the Illiniwek during the early 18th century. The first half of the 1720s was a time of more interaction between the Osage and French colonizers. Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont founded Fort Orleans in their territory; it was the first European colonial fort on the Missouri River. Jesuit missionaries were assigned to French forts and established missions in an attempt to convert the Osage, learning their language to ingratiate themselves. In 1724, the Osage allied with the French rather than the Spanish in their fight for control of the Mississippi region. In 1725, Bourgmont led a delegation of Osage and other tribal chiefs to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. They were shown around France, including a visit to Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

, Château de Marly and Fontainebleau. They hunted with Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

in the royal forest and saw an opera.

During the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

(the North American front of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

), France was defeated by Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

and in 1763 ceded control over their lands east of the River Mississippi to the British Crown. The French Crown

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the firs ...

made a separate deal with Spain, which took nominal control of much of the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

west of the great river. By the late 18th century, the Osage did extensive business with the French Creole fur trader René Auguste Chouteau, who was based in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

; the city was part of territory under nominal Spanish control after the Seven Years' War but was dominated by French colonists. They were the ''de facto'' European power in St. Louis and other settlements along the Mississippi, building their wealth on the fur trade. In return for the Chouteau brothers' building a fort in the village of the Great Osage southwest of St. Louis, the Spanish regional government gave the Chouteaus a six-year monopoly on trade (1794–1802). The Chouteaus named the post Fort Carondelet

Fort Carondelet was a fort located along the Osage River in Vernon County, Missouri, constructed in 1795 as an early fur trading post in Spanish Louisiana by the Chouteau family. The fort also was used by the Spanish colonial government to maint ...

after the Spanish governor. The Osage were pleased to have a fur trading post nearby, as it gave them access to manufactured goods and increased their prestige among the tribes. Lewis and Clark reported in 1804 that the peoples were the Great Osage on the Osage River, the Little Osage upstream, and the Arkansas band on the Verdigris River

The Verdigris River is a tributary of the Arkansas River in southeastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma in the United States. It is about long.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, ...

, a tributary of the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

. The Osage then numbered some 5,500. The Osage and Quapaw suffered extensive losses from smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

in 1801–1802. Historians estimate up to 2,000 Osage died in the epidemic.

In 1804 after the United States made the

In 1804 after the United States made the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, the U.S. government appointed the wealthy French fur trader Jean-Pierre Chouteau, a half-brother of René Auguste Chouteau, as the Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

assigned to the Osage. In 1809, he founded the Saint Louis Missouri Fur Company with his son Auguste Pierre Chouteau

Auguste Pierre Chouteau (9 May 1786 – 25 December 1838) was a member of the Chouteau fur-trading family who established trading posts in what is now the U.S. state of Oklahoma.

Chouteau was born in St. Louis, then part of Spanish colonial ...

and other prominent men of St. Louis, most of whom were of French-Creole descent, born in North America. Having lived with the Osage for many years and learned their language, Jean-Pierre Chouteau traded with them and made his home at present-day Salina, Oklahoma

Salina ( ) is a town in Mayes County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 1,396 at the 2010 census, a slight decline from the figure of 1,422 recorded in 2000.

History

For thousands of years indigenous peoples had lived along the rivers ...

, in the western part of their territory.

Wars with other tribes

The Choctaw chief

The Choctaw chief Pushmataha

Pushmataha (c. 1764 – December 24, 1824; also spelled Pooshawattaha, Pooshamallaha, or Poosha Matthaw), the "Indian General", was one of the three regional chiefs of the major divisions of the Choctaw in the 19th century. Many historians cons ...

, based in Mississippi, made his early reputation in battles against the Osage tribe in the area of southern Arkansas and their borderlands.

In the early 19th century, some Cherokee, such as Sequoyah, voluntarily removed from the southeast to the Arkansas River valley under pressure from European-American settlement in their traditional territory. They clashed there with the Osage, who controlled this area. The Osage regarded the Cherokee as invaders. They began raiding Cherokee towns, stealing horses, carrying off captives (usually women and children), and killing others, trying to drive out the Cherokee with a campaign of violence and fear. The Cherokee were not effective in stopping the Osage raids and worked to gain support from related tribes as well as whites. The peoples confronted each other in the " Battle of Claremore Mound," in which 38 Osage warriors were killed and 104 were taken captive by the Cherokee and their allies. As a result of the battle, the United States constructed Fort Smith in present-day Arkansas. It was intended to prevent armed confrontations between the Osage and other tribes. The U.S. compelled the Osage to cede additional land to the federal government in the treaty referred to as Lovely's Purchase.

In 1833, the Osage clashed with the Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

near the Wichita Mountains in modern-day south-central Oklahoma, in an incident known as the Cutthroat Gap massacre. The Osage cut off the heads of their victims and arranged them in rows of brass cooking buckets.Boyd, Maurice (1981): ''Kiowa Voices. Ceremonial Dance, Ritual and Song''. Fort Worth. No Osage died in this attack. Later, Kiowa warriors, allied with the Comanche, raided the Osage and others. In 1836, the Osage prohibited the Kickapoo from entering their Missouri reservation, pushing them back to ceded lands in Illinois.

U.S. interaction

After the Lewis and Clark Expedition was completed in 1806, Jefferson appointed Meriwether Lewis as Indian Agent for the territory of Missouri and the region. There were continuing confrontations between the Osage and other tribes in this area. Lewis anticipated that the U.S. would have to go to war with the Osage, because of their raids on eastern Natives and European-American settlements. However, the U.S. lacked sufficient military strength to coerce Osage bands into ceasing their raids. It decided to supply other tribes with weapons and ammunition, provided they attack the Osage to the point they "cut them off completely or drive them from their country."''Osage v. the United States of America,'' Indian Claims Commission For instance, in September 1807, Lewis persuaded the Potawatomie, Sac, andFox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelve sp ...

to attack an Osage village; three Osage warriors were killed. The Osage blamed the Americans for the attack. One of the Chouteau traders intervened and persuaded the Osage to conduct a buffalo hunt rather than seek retaliation by attacking Americans.

Lewis tried to control the Osage also by separating the friendly members from the hostile. In a letter dated August 21, 1808, that President Jefferson sent to Lewis, he says that he approves of the measures Lewis has taken in regards to making allies of the friendly Osage from those deemed as hostile. Jefferson writes, "we may go further, & as the principal obstacle to the Indians acting in large bodies is the want of provisions, we might supply that want, & ammunition also if they need it." But the goal foremost pursued by the US was to push the Osage out of areas being settled by European Americans, who began to enter the Louisiana Territory after the U.S. acquired it.

The lucrative fur trade continued to stimulate the growth of St. Louis and attracted more settlers there. It became a major port on the Mississippi River. The U.S. and Osage signed their first treaty on November 10, 1808, by which the Osage made a major cession of land in present-day Missouri. Under the Osage Treaty, they ceded to the federal government.

This treaty created a buffer line between the Osage and new European-American settlers in the Missouri Territory. It also established the requirement that the U.S. president had to approve all future land sales and cessions by the Osage. The Treaty of Ft. Osage states the U.S. would "protect" the Osage tribe "from the insults and injuries of other tribes of Indians, situated near the settlements of white people....". As was common in Native American relations with the federal government, the Osage found that the U.S. did not carry through on this commitment.

Reservations and missionaries

Between the first treaty with the U.S. and 1825, the Osage ceded their traditional lands across what are now Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma in the treaties of 1818 and 1825. In exchange, they were to receive reservation lands to the West and supplies to help them adapt to farming and a more settled culture. They were first relocated to a southeastKansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

reservation called the Osage Diminished Reserve. The city of Independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

later developed there. The first Osage reservation was a 50 by strip. The United Foreign Missionary Society sent clergy to them, supported by the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, Dutch Reformed

The Dutch Reformed Church (, abbreviated NHK) was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the original denomination of the Dutch Royal Family and ...

, and Associate Reformed churches. They established the Union, Harmony, and Hopefield missions.Joseph P. Key, "Review: 'Unaffected by the Gospel: Osage Resistance to the Christian Invasion, 1673-1906: A Cultural Victory' by Willard Hughes Rollings"''The Arkansas Historical Quarterly'', Vol. 64, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), accessed 8 April 2014 Cultural differences often led to conflicts, as the Protestants tried to impose their culture. The Catholic Church also sent missionaries. The Osage were attracted to their sense of mystery and ritual but felt the Catholics did not fully embrace the Osage sense of the spiritual incarnate in nature. During this period in Kansas, the tribe suffered from the widespread

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

pandemic of 1837–1838, which caused devastating losses among Native Americans from Canada to New Mexico. All clergy except the Catholics abandoned the Osage during the crisis. Most survivors of the epidemic had received vaccinations against the disease. The Osage believed that the loyalty of Catholic priests, who stayed with them and also died in the epidemic, created a special covenant between the tribe and the Catholic Church, but they did not convert in great number. Catholic clergy accompanied the Osage when they were forced to move again to Indian Territory in what became Oklahoma.

Honoring this special relationship, as well as Catholic sisters who taught their children in schools on reservations, numerous Osage elders went to the city of St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

in 2014 to celebrate its 250th anniversary of founding by the French. They participated in a mass partially conducted in Osage at St. Francis Xavier College Church of St. Louis University on April 2, 2014, as part of planned activities."Honoring the Osage", ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch'', 28 March 2014, p. A11 One of the con-celebrants was Todd Nance, who is the first Osage to be ordained as a Catholic priest.

In 1843, the Osage asked the federal government to send "Black Robes", Jesuit missionaries, to their reservation to educate their children; the Osage considered the Jesuits better able to work with their culture than the Protestant missionaries. The Jesuits also established a girls' school operated by the Sisters of Loretto

The Sisters of Loretto or the Loretto Community is a Catholic religious institute that strives "to bring the healing Spirit of God into our world." Founded in the United States in 1812 and based in the rural community of Nerinx, Kentucky, the ...

from Kentucky.Louis F. Burns, ''A History of the Osage People''University of Alabama Press, 1989/2004, pp. 226-227 and pp. 229-230 During a 35-year period, most of the missionaries were new recruits from Europe: Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. They taught, established more than 100 mission stations, built churches, and created the longest-running school system in Kansas.

Civil War and Indian wars

White squatters continued to be a frequent problem for the Osage, but they recovered from population losses, regaining a total of 5,000 members by 1850. TheKansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

resulted in numerous settlers arriving in Kansas; both abolitionists and pro-slavery groups were represented among those trying to establish residency in order to vote on whether the territory would have slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. The Osage lands became overrun with European-American settlers. In 1855, the Osage suffered another epidemic of smallpox, because a generation had grown up without getting vaccinated.Burns (1989/2004), ''History of Osage'', p. 241

Subsequent U.S. treaties and laws through the 1860s further reduced the lands of the Osage in Kansas. During the years of the Civil War, they were buffeted by both sides, as they were located between Union forts in the North, and Confederate forces and allies to the South. While the Osage tried to stay neutral, both sides raided their territory, taking horses and food stores. They struggled simply to survive through famine and the war. During the war, many Caddoan

The Caddoan languages are a family of languages native to the Great Plains spoken by tribal groups of the central United States, from present-day North Dakota south to Oklahoma. All Caddoan languages are critically endangered, as the number of ...

and Creek refugees from Indian Territory came to Osage country in Kansas, which further strained their resources. Although the Osage favored the Union by a five to one ratio, they made a treaty with the Confederacy to try to buy some peace.

Following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and victory of the Union, the Drum Creek Treaty

The Drum Creek Treaty came about from the controversy over the Sturges Treaty of 1868. The Sturges Osage Treaty was a treaty negotiated between the United States and the Osage Nation in 1868. The treaty was submitted to both the United States Ho ...

was passed by Congress on July 15, 1870, and ratified by the Osage at a meeting in Montgomery County, Kansas, on September 10, 1870. It provided that the remainder of Osage land in Kansas be sold, and the proceeds used to relocate the tribe to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

in the Cherokee Outlet

The Cherokee Outlet, or Cherokee Strip, was located in what is now the state of Oklahoma in the United States. It was a 60-mile-wide (97 km) parcel of land south of the Oklahoma-Kansas border between 96 and 100°W. The Cherokee Outlet wa ...

. By delaying agreement with removal, the Osage benefited by a change in administration. They sold their lands to the "peace" administration of President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, for which they received more money: $1.25 an acre rather than the 19 cents previously offered to them by the U.S.

In 1867, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

chose Osage scouts in his campaign against Chief Black Kettle and his band of Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

Indians in western Indian Territory. He knew the Osage for their scouting expertise, excellent terrain knowledge, and military prowess. Custer and his soldiers took Chief Black Kettle and his peaceful band by surprise in the early morning near the Washita River

The Washita River () is a river in the states of Texas and Oklahoma in the United States. The river is long and terminates at its confluence with the Red River, which is now part of Lake Texoma () on the TexasOklahoma border.

Geography

The ...

on November 27, 1868. They killed Chief Black Kettle, and the ambush resulted in additional deaths on both sides. This incident became known as the Battle of Washita River

The Battle of Washita River (also called Battle of the Washita or the Washita Massacre) occurred on November 27, 1868, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked Black Kettle's Southern Cheyenne camp on the Washita Rive ...

, or the Washita massacre, an ignominious part of the United States' Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

.

Removal to Indian territory

The Osage were one of the few American Indian nations to buy their own reservation. As a result, they retained more rights to the land and sovereignty. They retained mineral rights on their lands. Dennis McAuliffe (1994), ''The Deaths of Sybil Bolton: An American History,'' Times Books; republished a

The Osage were one of the few American Indian nations to buy their own reservation. As a result, they retained more rights to the land and sovereignty. They retained mineral rights on their lands. Dennis McAuliffe (1994), ''The Deaths of Sybil Bolton: An American History,'' Times Books; republished a(1994), ''Bloodland: A Family Story of Oil, Greed and Murder on the Osage Reservation''

Council Oak Books The reservation, of approximately , is coterminous with present-day

Osage County, Oklahoma

Osage County is the largest county by area in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Created in 1907 when Oklahoma was admitted as a state, the county is named for and is home to the federally recognized Osage Nation. The county is coextensive with the ...

, in the north-central portion of the state between Tulsa

Tulsa () is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 47th-most populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region with ...

and Ponca City

Ponca City ( iow, Chína Uhánⁿdhe) is a city in Kay County in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The city was named after the Ponca tribe. Ponca City had a population of 25,387 at the time of the 2010 census- and a population of 24,424 in the 2020 ...

.

The Osage established four towns: Pawhuska

Pawhuska ( osa, 𐓄𐓘𐓢𐓶𐓮𐓤𐓘 / hpahúska, ''meaning: "White Hair"'', iow, Paháhga) is a city in and the county seat of Osage County, Oklahoma, United States. It was named after the 19th-century Osage chief, ''Paw-Hiu-Skah'', ...

, Hominy, Fairfax, and Gray Horse

A gray horse (or grey horse) has a coat color characterized by progressive depigmentation of the colored hairs of the coat. Most gray horses have black skin and dark eyes; unlike some equine dilution genes and some other genes that lead to depig ...

. Each was dominated by one of the major bands at the time of removal. The Osage continued their relationship with the Catholic Church, which established schools operated by two orders of nuns, as well as mission churches.

It was many years before the Osage recovered from the hardships suffered during their last years in Kansas and their early years on the reservation in Indian Territory. For nearly five years during the depression of the 1870s, the Osage did not receive their full annuity in cash. Like other Native Americans, they suffered from the government's failure to provide full or satisfactory rations and goods as part of their annuities during this period. Middlemen made profits by shorting supplies to the Indians or giving them poor-quality food. Some people starved. Many adjustments had to be made to their new way of life.Warrior, Robert Allen. ''The People and the Word: Reading Native Nonfiction.'' Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2005. (80-81) Print.

During this time, Indian Office reports showed nearly a 50 percent decline in the Osage population. This resulted from the failure of the U.S. government to provide adequate medical supplies, food and clothing. The people suffered greatly during the winters. While the government failed to supply them, outlaws often smuggled whiskey to the Osage and the Pawnee.

In 1879, an Osage delegation went to Washington, D.C., and gained agreement to have all their annuities paid in cash; they hoped to avoid being continually shortchanged in supplies, or by being given supplies of inferior quality - spoiled food and inappropriate goods. They were the first Native American nation to gain full cash payment of annuities. They gradually began to build up their tribe again but suffered encroachment by white outlaws, vagabonds, and thieves.

The Osage wrote a constitution in 1881, modeling some parts of it after the United States Constitution. By the start of the 20th century, the federal government and progressives were continuing to press for Native American assimilation, believing this was the best policy for them. Congress passed the Curtis Act

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act; it resulted in the break-up of tribal governments and communal lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasa ...

and Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pres ...

, legislation requiring the dismantling of communal lands on other reservations. They allotted communal lands in 160-acre portions to individual households, declaring the remainder as "surplus" and selling it to non-natives. They also dismantled the tribal governments.

20th century to present

Oil discovery

In 1894 large quantities of oil were discovered to lie beneath the vast prairie owned by the tribe. Because of his recent work in developing oil production in Kansas, Henry Foster approached the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to request exclusive privileges to explore the Osage Reservation for oil and natural gas. Foster died shortly afterward, and his brother, Edwin B. Foster, assumed his interests. The BIA granted the request on March 16, 1896, with the stipulation that Foster was to pay the Osage tribe a 10% royalty on all sales of petroleum produced on the reservation. Foster found large quantities of oil, and the Osage benefited greatly monetarily. But this discovery of "black gold" eventually led to more hardships for tribal members. The Osage had learned about negotiating with the U.S. government. Through the efforts of Principal Chief James Bigheart, in 1907 they reached a deal which enabled them to retain communal mineral rights on the reservation lands. These were later found to have large quantities of crude oil, and tribal members benefited from royalty revenues from oil development and production. The government leased lands on their behalf for oil development; the companies/government sent the Osage members royalties that, by the 1920s, had dramatically increased their wealth. In 1923 alone, the Osage earned $30 million in royalties. Since the early 20th century, they are the only tribe within the state of Oklahoma to retain a federally recognized reservation.2011 "Osage Reservation"

The Osage had learned about negotiating with the U.S. government. Through the efforts of Principal Chief James Bigheart, in 1907 they reached a deal which enabled them to retain communal mineral rights on the reservation lands. These were later found to have large quantities of crude oil, and tribal members benefited from royalty revenues from oil development and production. The government leased lands on their behalf for oil development; the companies/government sent the Osage members royalties that, by the 1920s, had dramatically increased their wealth. In 1923 alone, the Osage earned $30 million in royalties. Since the early 20th century, they are the only tribe within the state of Oklahoma to retain a federally recognized reservation.2011 "Osage Reservation", ''Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory,'' Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission, 2011: 24. Retrieved 24 Jan 2012 In 2000 the Osage sued the federal government over its management of the trust assets, alleging that it had failed to pay tribal members appropriate royalties, and had not historically protected the land assets and appreciation. The suit was settled in 2011 for $380 million, and a commitment by the government to make numerous changes to improve the program. In 2016, the Osage nation bought

Ted Turner

Robert Edward "Ted" Turner III (born November 19, 1938) is an American entrepreneur, television producer, media proprietor, and philanthropist. He founded the Cable News Network (CNN), the first 24-hour cable news channel. In addition, he fo ...

's Bluestem ranch.

Osage Allotment Act

In 1889, the U.S. federal government claimed to no longer recognize the legitimacy of a governing Osage National Council, which the people had created in 1881, with a constitution that adopted some aspects of that of the United States. In 1906, as part of the Osage Allotment Act, the U.S. Congress created the Osage Tribal Council to handle affairs of the tribe. It extinguished the power of tribal governments in order to enable the admission of the Indian Territory as part of the state of Oklahoma in 1907. As the Osage owned their land, they were in a stronger position than other tribes. The Osage were unyielding in refusing to give up their lands and held up statehood for Oklahoma before signing an allotment act. They were forced to accept allotment but retained their "surplus" land after allotment to households, and apportioned it to individual members. Each of the 2,228 registered Osage members in 1906 (and one non-Osage) received 657 acres, nearly four times the amount of land (usually 160 acres) that most Native American households were allotted in other places when communal lands were distributed. In addition, the tribe retained communalmineral rights

Mineral rights are property rights to exploit an area for the minerals it harbors. Mineral rights can be separate from property ownership (see Split estate). Mineral rights can refer to sedentary minerals that do not move below the Earth's surfac ...

to what was below the surface. As development of resources took place, members of the tribe received royalties according to their headrights, paid according to the amount of land they held.

Although the Osage were encouraged to become settled farmers, their land was the poorest in the Indian Territory for agricultural purposes. They survived by subsistence farming, later enhanced by raising stock. They leased lands to ranchers for grazing and earned income from the resulting fees. In addition to breaking up communal land, the act replaced tribal government with the Osage National Council, to which members were to be elected to conduct the tribe's political, business, and social affairs. Under the act, initially each Osage male had equal voting rights to elect members of the council, and the principal and assistant principal chiefs. The rights to these lands in future generations was divided among legal heirs, as were the mineral headrights to mineral lease royalties. Under the Allotment Act, only allottees and their descendants who held headrights could vote in the elections or run for office (originally restricted to males). The members voted by their headrights, which generated inequalities among the voters.

A 1992 U.S. district court decision ruled that the Osage could vote to reinstate the Osage National Council as city members of the Osage nation, rather than being required to vote by headright. This decision was reversed in 1997 with the United States Court of Appeals ruling that ended the government restoration. In 2004, Congress passed legislation to restore sovereignty to the Osage Nation and enable them to make their own decisions about government and membership qualifications for their people.

In March 2010, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (in case citations, 10th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* District of Colorado

* District of Kansas

* Distr ...

held that the 1906 Allotment Act had disestablished the Osage reservation established in 1872. This ruling potentially affected the legal status of three of the seven Osage casinos, including the largest one in Tulsa

Tulsa () is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 47th-most populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region with ...

, as it meant the casino was not on federal trust land. Federal Indian gaming law allows tribes to operate casinos only on trust land.

The Osage Nation's largest economic enterprise, Osage Casino

The Osage Nation operates seven casinos in Oklahoma, under the name Osage Casinos. The 25th largest tribe in the United States, the people are based on their reservation encompassing Osage County, Oklahoma. It is larger than the U.S. states of De ...

s, officially opened newly constructed casinos, hotels and convenience stores in Skiatook and Ponca City in December 2013.

Natural resources and headrights

Before having a vote within the tribe on the question of allotment, the Osage demanded that the government purge their tribal rolls of people who were not legally Osage. The Indian agent had been adding names of persons who were not approved by the tribe, and the Osage submitted a list of more than 400 persons to be investigated. Because the government removed few of the fraudulent people, the Osage had to share their land and oil rights with people who did not belong. But, the Osage had negotiated keeping communal control of the mineral rights. The act stated that all persons listed on tribal rolls prior to January 1, 1906 or born before July 1907 (allottees) would be allocated a share of the reservation's subsurface natural resources, regardless ofblood quantum

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws in the United States that define Native American status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to estab ...

. The headright could be inherited by legal heirs. This communal claim to mineral resources was due to expire in 1926. After that, individual landowners would control the mineral rights to their plots. This provision heightened the pressure for those whites who were eager to gain control of Osage lands before the deadline.

Although the Osage Allotment Act protected the tribe's mineral rights for two decades, any adult "of a sound mind" could sell surface land. In the time between 1907 and 1923, Osage individuals sold or leased thousands of acres to non-Indians of formerly restricted land. At the time, many Osage did not understand the value of such contracts and often were taken advantage of by unscrupulous businessmen, con artists, and others trying to grab part of their wealth. Non-Native Americans also tried to cash in on the new Osage wealth by marrying into families with headrights.

Osage Indian murders

Alarmed about the way the Osage were using their wealth, in 1921 the U.S. Congress passed a law requiring any Osage of half or more Indian ancestry to be appointed a guardian until proving "competency". Minors with less than half Osage ancestry were required to have guardians appointed, even if their parents were living. This system was not administered by federal courts; rather, local courts appointed guardians from among white attorneys and businessmen. By law, the guardians provided a $4,000 annual allowance to their charges, but initially the government required little record keeping of how they invested the difference. Royalties to persons holding headrights were much higher: $11,000–12,000 per year during the period 1922–1925. Guardians were permitted to collect $200–1,000 per year, and the attorney involved could collect $200 per year, which was withdrawn from each Osage's income. Some attorneys served as guardians and did so for four Osage at once, allowing them to collect $4,800 per year. The tribe auctioned off development rights of their mineral assets for millions of dollars. According to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in 1924 the total revenue of the Osage from the mineral leases was $24,670,483. After the tribe auctioned mineral leases and more land was explored, the oil business on the Osage reservation boomed. Tens of thousands of oil workers arrived, more than 30 boom towns sprang up and, nearly overnight, Osage headright holders became the "richest people in the world." When royalties peaked in 1925, annual headright earnings were $13,000. A family of four who were all on the allotment roll earned $52,800, comparable to approximately $600,000 in today's economy. The guardianship program created an incentive for corruption, and many Osage were legally deprived of their land, headrights, and/or royalties. Others were murdered, in cases the police generally failed to investigate. The coroner's office colluded by falsifying death certificates, for instance claiming suicides when people had been poisoned. The Osage Allotment Act did not entitle the Native Americans to autopsies, so many deaths went unexamined. In the early 1920s there was a rise in murders and suspicious deaths of Osage, called the "Reign of Terror." In one plot, in 1921, Ernest Burkhart, a European American, married Molly Kyle, an Osage woman with headrights. His uncle William "King of Osage Hills" Hale, a powerful business man who led the plot, and brother Bryan hired accomplices to murder Kyle family heirs. They arranged for the murders of Kyle's mother, two sisters, a brother-in-law, and a cousin, in cases involving poisoning, bombing, and shooting. With local and state officials unsuccessful at solving the murders, in 1925 the Osage requested the help of theFederal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

. It was the bureau's first murder case. By the time it started investigating, Kyle was already being poisoned. This was discovered and she survived. She had inherited the headrights of the rest of her family. The FBI achieved the prosecution and conviction of the principals in the Kyle family murders. From 1921 to 1925, however, an estimated 60 Osage were killed, and most murders were not solved. John Joseph Mathews, an Osage, explored the disruptive social consequences of the oil boom for the Osage Nation in his semi-autobiographical novel ''Sundown'' (1934). ''Killers of the Flower Moon

''Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI'' is the third non-fiction book by the American journalist David Grann. The book was released on April 18, 2017 by Doubleday. ''Time'' magazine listed ''Killers of the Fl ...

: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI'' (2017) by David Grann

David Elliot Grann (born March 10, 1967) is an American journalist, a staff writer for ''The New Yorker'' magazine, and a best-selling author.

His first book, '' The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon,'' was published by D ...

was a National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

finalist; a related major motion picture is in development.

Changes to law and management claims

As a result of the murders and increasing problems with trying to protect Osage oil wealth, in 1925 Congress passed legislation limiting inheritance of headrights only to those heirs of half or more Osage ancestry. In addition, they extended the tribal control of mineral rights for another 20 years; later legislation gave the tribe continuing communal control indefinitely. Today, headrights have been passed down primarily among descendants of the Osage who originally possessed them. But the Bureau of Indian Affairs has estimated that 25% of headrights are owned by non-Osage people, including other American Indians, non-Indians, churches, and community organizations. It continues to pay royalties on mineral revenues on a quarterly basis. Beginning in 1999, the Osage Nation sued the United States in the Court of Federal Claims (dockets 99-550 and 00-169) for mismanaging its trust funds and its mineral estate. The litigation eventually included claims reaching into the 19th century. In February 2011, the Court of Federal Claims awarded $330.7 million in damages in partial compensation for some of the mismanagement claims, covering the period from 1972 to 2000. On October 14, 2011, the United States settled the outstanding litigation for a total of $380 million. The tribe has about 16,000 members. The settlement includes commitments by the United States to cooperate with the Osage to institute new procedures to protect tribal trust funds and resource management.Mineral Council

The Osage Tribal Council was created under the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. It consisted of a principal chief, an assistant principal chief, and eight members of the Osage tribal council. The mineral estate consists of more than natural gas and petroleum. Although these two resources have yielded the most profit, the Osage have also earned revenue from leases for the mining of lead, zinc, limestone, and coal deposits. Water may also be considered a profitable asset that is controlled by the Mineral Council.

The first elections for this council were held in 1908 on the first Monday in June. Officers were elected for a term of two years, which made it difficult for them to accomplish long-term goals. If for some reason the principal chief's office becomes vacant, a replacement is elected by the remaining council members. Later in the 20th century, the tribe increased the terms of office of council members to four years. In 1994 by referendum, the tribe voted for a new constitution; among its provisions was the separation of the Mineral Council, or Mineral Estate, from regular tribal government. According to the constitution, only Osage members who are also headright holders can vote for the members of the Mineral Council. It is as if they were shareholders of a corporation.

The Osage Tribal Council was created under the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. It consisted of a principal chief, an assistant principal chief, and eight members of the Osage tribal council. The mineral estate consists of more than natural gas and petroleum. Although these two resources have yielded the most profit, the Osage have also earned revenue from leases for the mining of lead, zinc, limestone, and coal deposits. Water may also be considered a profitable asset that is controlled by the Mineral Council.

The first elections for this council were held in 1908 on the first Monday in June. Officers were elected for a term of two years, which made it difficult for them to accomplish long-term goals. If for some reason the principal chief's office becomes vacant, a replacement is elected by the remaining council members. Later in the 20th century, the tribe increased the terms of office of council members to four years. In 1994 by referendum, the tribe voted for a new constitution; among its provisions was the separation of the Mineral Council, or Mineral Estate, from regular tribal government. According to the constitution, only Osage members who are also headright holders can vote for the members of the Mineral Council. It is as if they were shareholders of a corporation.

Modern day

Government

By a new constitution of 1994, the Osage voted that original allottees and their direct descendants, regardless of blood quantum, were citizen members of the Osage Nation. This constitution was overruled through court judgments. The Osage appealed to Congress for support to create their own government and membership rules. In 2004, President George W. Bush signed Public Law 108–431, "An Act to Reaffirm the Inherent Sovereign Rights of the Osage Tribe to Determine Its Membership and Form a Government."Hokiahse Iba, Priscilla"Osage Government Reform"

Arizona Native Net

, 2006. Retrieved on 2009-10-05. From 2004 to 2006, the Osage Government Reform Commission formed and worked to develop a new government. It explored "sharply differing visions arose of the new government's goals, the nation's own history, and what it means to be Osage. The primary debates were focused on biology, culture, natural resources, and sovereignty."Jean Dennison, ''Colonial Entanglement: Constituting a Twenty-First-Century Osage Nation''

UNC Press Books, 2012, Introduction The Reform Commission held weekly meetings to develop a referendum that Osage members could vote upon in order to develop and reshape the Osage Nation government and its policies. On March 11, 2006, the people ratified the constitution in a second referendum vote. Its major provision was to provide "

one man, one vote

"One man, one vote", or "one person, one vote", expresses the principle that individuals should have equal representation in voting. This slogan is used by advocates of political equality to refer to such electoral reforms as universal suffrage, ...