Ophthalmology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ophthalmology ( ) is a

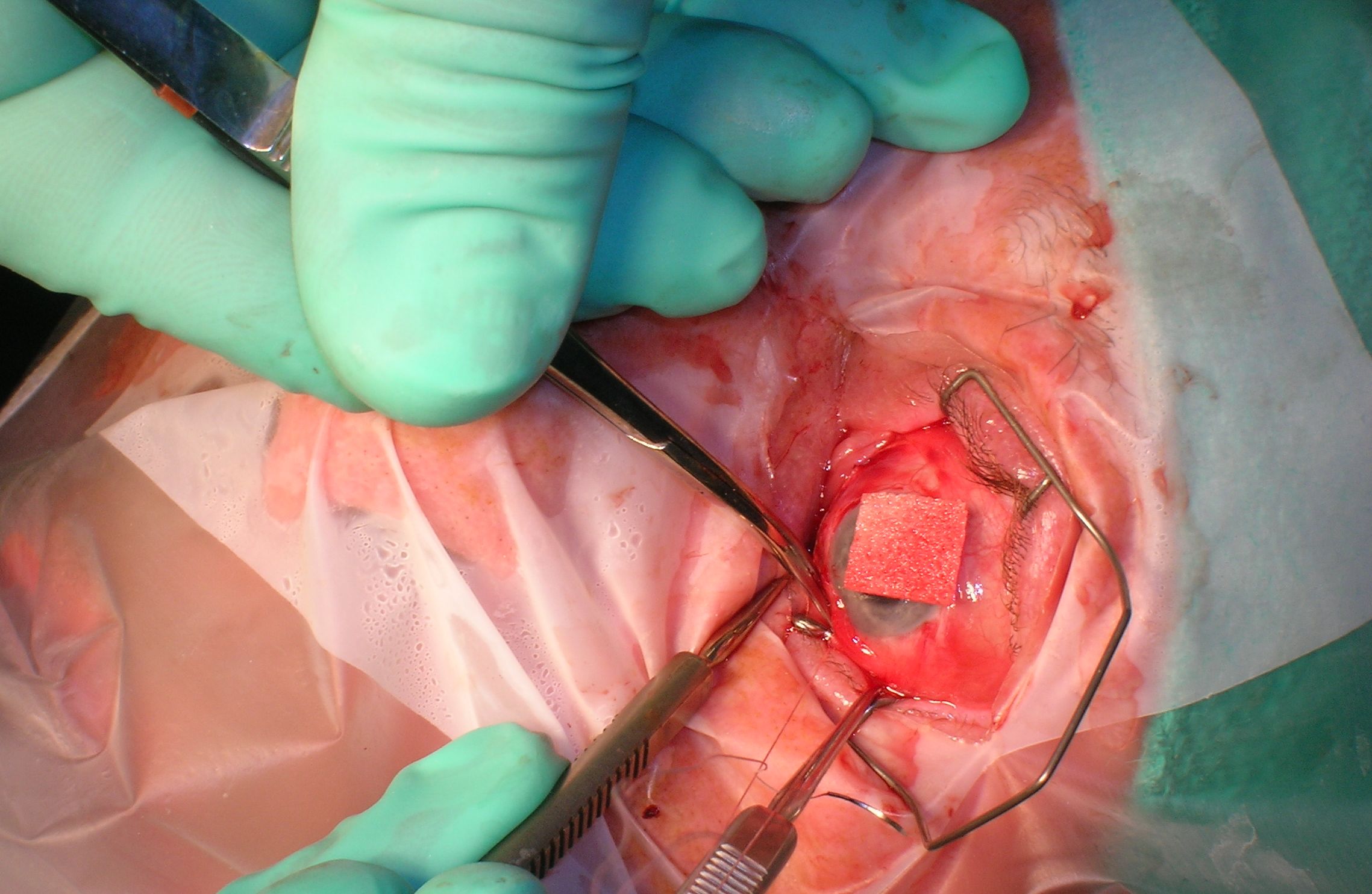

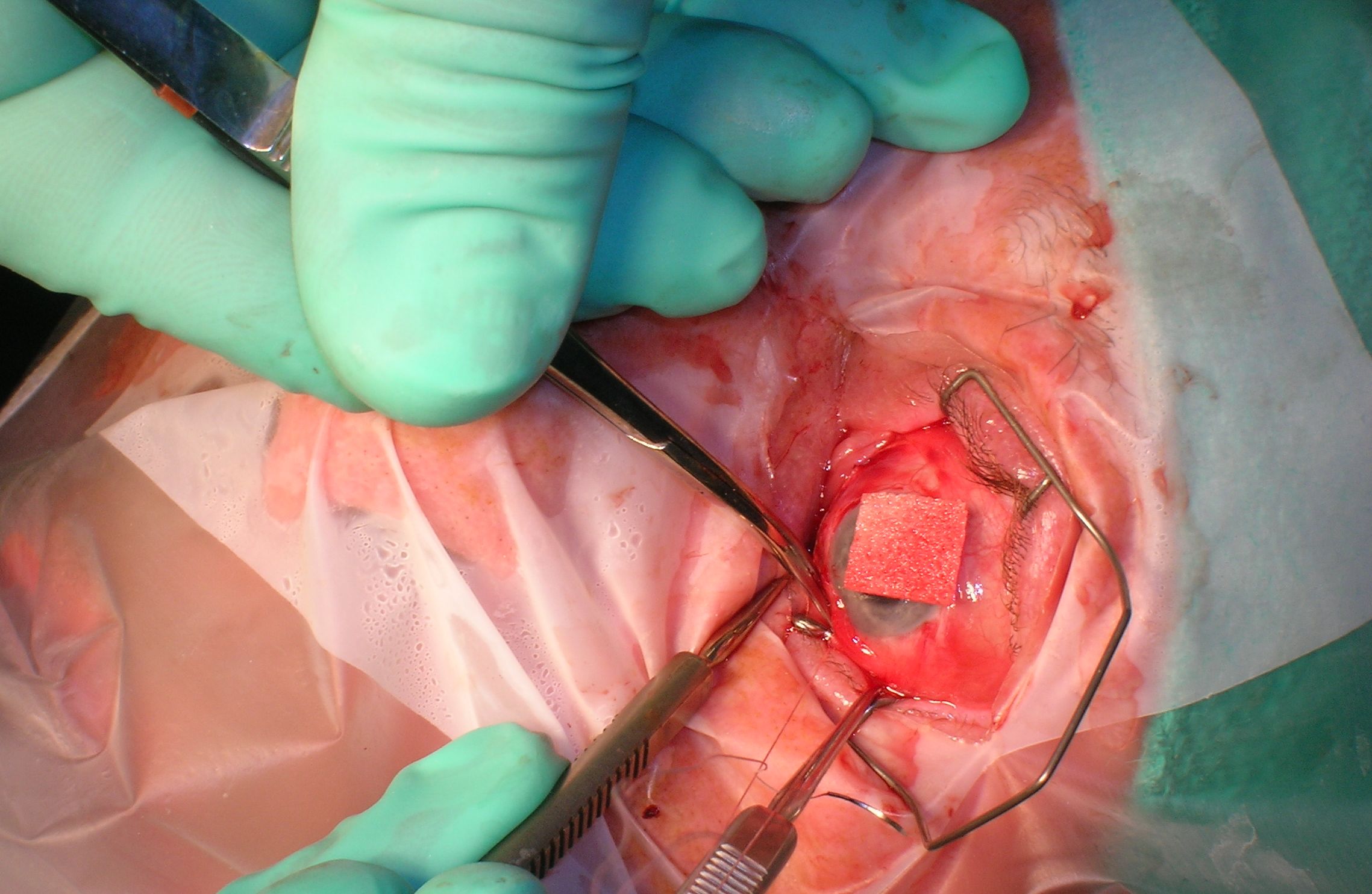

Eye surgery, also known as ocular surgery, is surgery performed on the eye or its adnexa by an ophthalmologist. The eye is a fragile organ, and requires extreme care before, during, and after a surgical procedure. An eye surgeon is responsible for selecting the appropriate surgical procedure for the patient and for taking the necessary safety precautions.

Eye surgery, also known as ocular surgery, is surgery performed on the eye or its adnexa by an ophthalmologist. The eye is a fragile organ, and requires extreme care before, during, and after a surgical procedure. An eye surgeon is responsible for selecting the appropriate surgical procedure for the patient and for taking the necessary safety precautions.

Ophthalmologists typically complete four years of undergraduate studies, four years of medical school and four years of eye-specific training (residency). Some pursue additional training, known as a fellowship - typically one to two years. Ophthalmologists are physicians who specialize in the eye and related structures. They perform medical and surgical eye care and may also write prescriptions for corrective lenses. They often manage late stage eye disease, which typically involves surgery.

Ophthalmologists must complete the requirements of continuing medical education to maintain licensure and for recertification.

Ophthalmologists typically complete four years of undergraduate studies, four years of medical school and four years of eye-specific training (residency). Some pursue additional training, known as a fellowship - typically one to two years. Ophthalmologists are physicians who specialize in the eye and related structures. They perform medical and surgical eye care and may also write prescriptions for corrective lenses. They often manage late stage eye disease, which typically involves surgery.

Ophthalmologists must complete the requirements of continuing medical education to maintain licensure and for recertification.

* Allvar Gullstrand (1862–1930) (Sweden) was a

* Allvar Gullstrand (1862–1930) (Sweden) was a

EyeWiki

Aaojournal

{{Authority control Surgical specialties

surgical

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

subspecialty within medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a medical degree

A medical degree is a professional degree admitted to those who have passed coursework in the fields of medicine and/or surgery from an accredited medical school. Obtaining a degree in medicine allows for the recipient to continue on into special ...

, a doctor specialising in ophthalmology must pursue additional postgraduate residency training specific to that field. This may include a one-year integrated internship that involves more general medical training in other fields such as internal medicine or general surgery. Following residency, additional specialty training (or fellowship) may be sought in a particular aspect of eye pathology.

Ophthalmologists prescribe medications to treat eye diseases, implement laser therapy, and perform surgery when needed. Ophthalmologists provide both primary and specialty eye care - medical and surgical. Most ophthalmologists participate in academic research on eye diseases at some point in their training and many include research as part of their career.

Ophthalmology has always been at the forefront of medical research with a long history of advancement and innovation in eye care.

Diseases

A brief list of some of the most common diseases treated by ophthalmologists: *Cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

* Excessive tearing (tear duct obstruction)

* Proptosis (bulged eyes)

* Thyroid eye disease

* Eye tumors

* Ptosis

* Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (also known as diabetic eye disease), is a medical condition in which damage occurs to the retina due to diabetes mellitus. It is a leading cause of blindness in developed countries.

Diabetic retinopathy affects up to 80 perc ...

* Dry eye syndrome

Dry eye syndrome (DES), also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is the condition of having dry eyes. Other associated symptoms include irritation, redness, discharge, and easily fatigued eyes. Blurred vision may also occur. Symptoms range ...

* Glaucoma

* Macular degeneration

* Retinal detachment

* Endophthalmitis

* Refractive errors

Refractive error, also known as refraction error, is a problem with focusing light accurately on the retina due to the shape of the eye and or cornea. The most common types of refractive error are near-sightedness, far-sightedness, astigmatism, ...

* Strabismus

Strabismus is a vision disorder in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. The eye that is focused on an object can alternate. The condition may be present occasionally or constantly. If present during a ...

(misalignment or deviation of eyes)

* Uveitis

Uveitis () is inflammation of the uvea, the pigmented layer of the eye between the inner retina and the outer fibrous layer composed of the sclera and cornea. The uvea consists of the middle layer of pigmented vascular structures of the eye and in ...

* Ocular trauma

* Ruptured globe injury

* Orbital fracture

Facial trauma, also called maxillofacial trauma, is any physical trauma to the face. Facial trauma can involve soft tissue injuries such as burns, lacerations and bruises, or fractures of the facial bones such as nasal fractures and fractures ...

Diagnosis

Eye examination

Following are examples of examination methods performed during aneye examination

An eye examination is a series of tests performed to assess vision and ability to focus on and discern objects. It also includes other tests and examinations pertaining to the eyes. Eye examinations are primarily performed by an optometrist, ...

that enables diagnosis

* Visual acuity assessment

* Ocular tonometry to determine intraocular pressure

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is the fluid pressure inside the eye. Tonometry is the method eye care professionals use to determine this. IOP is an important aspect in the evaluation of patients at risk of glaucoma. Most tonometers are calibrated t ...

* Extraocular motility and ocular alignment assessment

* Slit lamp examination

* Dilated fundus examination

* Gonioscopy

Gonioscopy a routine ophthalmological procedure that measures the angle between the iris and the cornea (the iridocorneal angle), using a goniolens (also known as a gonioscope) together with a slit lamp or operating microscope. Its use is import ...

* Refraction

Specialized tests

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a medical technological platform used to assess ocular structures. The information is then used by physicians to assess staging of pathological processes and confirm clinical diagnoses. Subsequent OCT scans are used to assess the efficacy of managing diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma.Optical coherence tomography angiography Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) is a non-invasive imaging technique based on optical coherence tomography (OCT) developed to visualize vascular networks in the human retina, choroid, skin and various animal models. OCTA may make u ...

(OCTA) and Fluorescein angiography

Fluorescein angiography (FA), fluorescent angiography (FAG), or fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) is a technique for examining the circulation of the retina and choroid (parts of the fundus) using a fluorescent dye and a specialized camera. S ...

to visualize the vascular networks of the retina and choroid.

Electroretinography

Electroretinography measures the electrical responses of various cell types in the retina, including the photoreceptors ( rods and cones), inner retinal cells ( bipolar and amacrine cells), and the ganglion cells. Electrodes are placed on th ...

(ERG) measures the electrical responses of various cell types in the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

, including the photoreceptors ( rods and cones

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines conn ...

), inner retinal cells ( bipolar and amacrine cells), and the ganglion cells.

Electrooculography

Electrooculography (EOG) is a technique for measuring the corneo-retinal standing potential that exists between the front and the back of the human eye. The resulting signal is called the electrooculogram. Primary applications are in ophthalmol ...

(EOG) is a technique for measuring the corneo-retinal standing potential that exists between the front and the back of the human eye. The resulting signal is called the electrooculogram. Primary applications are in ophthalmological diagnosis and in recording eye movements.

Visual field testing to detect dysfunction in central and peripheral vision

Peripheral vision, or ''indirect vision'', is vision as it occurs outside the point of fixation, i.e. away from the center of gaze or, when viewed at large angles, in (or out of) the "corner of one's eye". The vast majority of the area in th ...

which may be caused by various medical conditions such as glaucoma, stroke, pituitary disease, brain tumours or other neurological deficits.

Corneal topography is a non-invasive

A medical procedure is defined as ''non-invasive'' when no break in the skin is created and there is no contact with the mucosa, or skin break, or internal body cavity beyond a natural or artificial body orifice. For example, deep palpation and p ...

medical imaging technique for mapping the anterior curvature of the cornea, the outer structure of the eye.

Ultrasonography of the eyes may be performed by an ophthalmologist.

Ophthalmic surgery

Eye surgery, also known as ocular surgery, is surgery performed on the eye or its adnexa by an ophthalmologist. The eye is a fragile organ, and requires extreme care before, during, and after a surgical procedure. An eye surgeon is responsible for selecting the appropriate surgical procedure for the patient and for taking the necessary safety precautions.

Eye surgery, also known as ocular surgery, is surgery performed on the eye or its adnexa by an ophthalmologist. The eye is a fragile organ, and requires extreme care before, during, and after a surgical procedure. An eye surgeon is responsible for selecting the appropriate surgical procedure for the patient and for taking the necessary safety precautions.

Subspecialties

Ophthalmology includes subspecialities that deal either with certain diseases or diseases of certain parts of the eye. Some of them are: * Anterior segment surgery * Cornea, ocular surface, and external disease * Glaucoma *Neuro-ophthalmology

Neuro-ophthalmology is an academically-oriented subspecialty that merges the fields of neurology and ophthalmology, often dealing with complex systemic diseases that have manifestations in the visual system. Neuro-ophthalmologists initially complet ...

* Ocular oncology

Eye neoplasms can affect all parts of the eye, and can be a benign tumor or a malignant tumor (cancer). Eye cancers can be primary (starts within the eye) or metastatic cancer (spread to the eye from another organ). The two most common cancers t ...

* Oculoplastics and orbit surgery

* Ophthalmic pathology

* Paediatric ophthalmology/strabismus

Strabismus is a vision disorder in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. The eye that is focused on an object can alternate. The condition may be present occasionally or constantly. If present during a ...

(misalignment of the eyes)

* Refractive surgery

* Medical retina, deals with treatment of retinal problems through non-surgical means

* Uveitis

Uveitis () is inflammation of the uvea, the pigmented layer of the eye between the inner retina and the outer fibrous layer composed of the sclera and cornea. The uvea consists of the middle layer of pigmented vascular structures of the eye and in ...

* Veterinary

Veterinary medicine is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, management, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, disorder, and injury in animals. Along with this, it deals with animal rearing, husbandry, breeding, research on nutri ...

specialty training programs in veterinary ophthalmology exist in some countries.

* Vitreo-retinal surgery, deals with surgical management of retinal and posterior segment diseases

Medical retina and vitreo-retinal surgery sometimes are combined and together they are called posterior segment

The posterior segment or posterior cavity is the back two-thirds of the eye that includes the anterior hyaloid membrane and all of the optical structures behind it: the vitreous humor, retina, choroid, and optic nerve.Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

roots of the word ophthalmology are ὀφθαλμός (, "eye") and -λoγία (-, "study, discourse"), i.e., "the study of eyes". The discipline applies to all animal eyes, whether human or not, since the practice and procedures are quite similar with respect to disease processes, although there are differences in the anatomy or disease prevalence.

History

Ancient near east and the Greek period

In the Ebers Papyrus from ancient Egypt dating to 1550 BC, a section is devoted to eye diseases. Prior toHippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

, physicians largely based their anatomical conceptions of the eye on speculation, rather than empiricism. They recognized the sclera and transparent cornea running flushly as the outer coating of the eye, with an inner layer with pupil, and a fluid at the centre. It was believed, by Alcamaeon

Alcmaeon of Croton (; el, Ἀλκμαίων ὁ Κροτωνιάτης, ''Alkmaiōn'', ''gen''.: Ἀλκμαίωνος; fl. 5th century BC) was an early Greek medical writer and philosopher-scientist. He has been described as one of the most e ...

(fifth century BC) and others, that this fluid was the medium of vision and flowed from the eye to the brain by a tube. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

advanced such ideas with empiricism. He dissected the eyes of animals, and discovering three layers (not two), found that the fluid was of a constant consistency with the lens forming (or congealing) after death, and the surrounding layers were seen to be juxtaposed. He and his contemporaries further put forth the existence of three tubes leading from the eye, not one. One tube from each eye met within the skull.

The Greek physician Rufus of Ephesus

Rufus of Ephesus ( el, Ῥοῦφος ὁ Ἐφέσιος, fl. late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD) was a Greek physician and author who wrote treatises on dietetics, pathology, anatomy, gynaecology, and patient care. He was an admirer of Hip ...

(first century AD) recognised a more modern concept of the eye, with conjunctiva, extending as a fourth epithelial layer over the eye. Rufus was the first to recognise a two-chambered eye, with one chamber from cornea to lens (filled with water), the other from lens to retina (filled with a substance resembling egg whites).

Celsus

Celsus (; grc-x-hellen, Κέλσος, ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work, ''The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: grc-x-hellen, Λόγ� ...

the Greek philosopher of the second century AD gave a detailed description of cataract surgery by the couching method.

The Greek physician Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

(second century AD) remedied some mistaken descriptions, including about the curvature of the cornea and lens, the nature of the optic nerve, and the existence of a posterior chamber. Although this model was a roughly correct modern model of the eye, it contained errors. Still, it was not advanced upon again until after Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

. A ciliary body

The ciliary body is a part of the eye that includes the ciliary muscle, which controls the shape of the lens, and the ciliary epithelium, which produces the aqueous humor. The aqueous humor is produced in the non-pigmented portion of the ciliar ...

was then discovered and the sclera, retina, choroid, and cornea were seen to meet at the same point. The two chambers were seen to hold the same fluid, as well as the lens being attached to the choroid. Galen continued the notion of a central canal, but he dissected the optic nerve and saw that it was solid. He mistakenly counted seven optical muscles, one too many. He also knew of the tear ducts.

Ancient India

The Indian surgeon Sushruta wrote the '' Sushruta Samhita'' inSanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

in approximately the sixth century BC, which describes 76 ocular diseases (of these, 51 surgical) as well as several ophthalmological surgical instruments and techniques. His description of cataract surgery

Cataract surgery, also called lens replacement surgery, is the removal of the natural lens of the eye (also called "crystalline lens") that has developed an opacification, which is referred to as a cataract, and its replacement with an intra ...

was compatible with the method of couching. He has been described as one of the first cataract surgeons.

Medieval Islam

Medieval Islamic Arabic and Persian scientists (unlike their classical predecessors) considered it normal to combine theory and practice, including the crafting of precise instruments, and therefore, found it natural to combine the study of the eye with the practical application of that knowledge.Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, أبو زيد حنين بن إسحاق العبادي; (809–873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

, and others beginning with the medieval Arabic period, taught that the crystalline lens is in the exact center of the eye. This idea was propagated until the end of the 1500s.

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), in his Book of Optics explained that vision occurs when light lands on an object, bounces off, and is directed to one's eyes.

Ibn al-Nafis, an Arabic native of Damascus, wrote a large textbook, ''The Polished Book on Experimental Ophthalmology'', divided into two parts, ''On the Theory of Ophthalmology'' and ''Simple and Compounded Ophthalmic Drugs''.

Avicenna wrote in his Canon "rescheth", which means "retiformis", and Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libraries at Toledo. Some of ...

translated this at approximately 1150 into the new term "retina".

Modern Period

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,hand lens

A magnifying glass is a convex lens that is used to produce a magnified image of an object. The lens is usually mounted in a frame with a handle. A magnifying glass can be used to focus light, such as to concentrate the sun's radiation to crea ...

es were used by Malpighi, microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

s by Leeuwenhoek, preparations for fixing the eye for study by Ruysch, and later the freezing of the eye by Petit. This allowed for detailed study of the eye and an advanced model. Some mistakes persisted, such as: why the pupil changed size (seen to be vessels of the iris filling with blood), the existence of the posterior chamber, and the nature of the retina. Unaware of their functions, Leeuwenhoek noted the existence of photoreceptors, however, they were not properly described until Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus in 1834.

Approximately 1750, Jacques Daviel advocated a new treatment for cataract by extraction instead of the traditional method of couching. Georg Joseph Beer (1763–1821) was an Austrian ophthalmologist and leader of the First Viennese School of Medicine. He introduced a flap operation for treatment of cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

(Beer's operation), as well as having popularized the instrument used to perform the surgery (Beer's knife).

In North America, indigenous healers treated some eye diseases by rubbing or scraping the eyes or eyelids.

Ophthalmic surgery in Great Britain

The first ophthalmic surgeon in Great Britain was John Freke, appointed to the position by the governors of St. Bartholomew's Hospital in 1727. A major breakthrough came with the appointment of Baron de Wenzel (1724–90), a German who became the oculist toKing George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

of Great Britain in 1772. His skill at removing cataracts legitimized the field. The first dedicated ophthalmic hospital opened in 1805 in London; it is now called Moorfields Eye Hospital

Moorfields Eye Hospital is a specialist NHS eye hospital in Finsbury in the London Borough of Islington in London, England run by Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Together with the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, which is adjacen ...

. Clinical developments at Moorfields and the founding of the Institute of Ophthalmology (now part of the University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

) by Sir Stewart Duke-Elder

Sir William Stewart Duke-Elder (22 April 1898 – 27 March 1978), a Scottish ophthalmologist who was a dominant force in his field for more than a quarter of a century.

Life

Duke-Elder was born in the manse in Tealing near Dundee. His fat ...

established the site as the largest eye hospital in the world and a nexus for ophthalmic research.

Central Europe

In Berlin, ophthalmologistAlbrecht von Graefe Albrecht von Graefe may refer to:

* Albrecht von Graefe (ophthalmologist) (1828-1870), Prussian opthalmologist

* Albrecht von Graefe (politician)

Albrecht von Graefe (1 January 1868 – 18 April 1933) was a German landowner and right-wing ...

introduced iridectomy as a treatment for glaucoma and improved cataract surgery, he is also considered the founding father of the German Ophthalmological Society.

Numerous ophthalmologists fled Germany after 1933 as the Nazis began to persecute those of Jewish descent. A representative leader was Joseph Igersheimer (1879–1965), best known for his discoveries with arsphenamine for the treatment of syphilis. He fled to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

in 1933. As one of eight emigrant directors in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Istanbul

, image = Istanbul_University_logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, latin_name = Universitas Istanbulensis

, motto = tr, Tarihten Geleceğe Bilim Köprüsü

, mottoeng = Science Bridge from Past to the Future

, established = 1453 1846 1933

...

, he built a modern clinic and trained students. In 1939, he went to the United States, becoming a professor at Tufts University. German ophthalmologist, Gerhard Meyer-Schwickerath

Gerhard Rudolph Edmund Meyer-Schwickerath (10 July 1920 – 20 January 1992) was German ophthalmologist university lecturer and researcher. He is known as the father of light coagulation which was the predecessor to many eye surgeries.

Early li ...

is widely credited with developing the predecessor of laser coagulation, photocoagulation.

In 1946, Igersheimer conducted the first experiments on light coagulation. In 1949, he performed the first successful treatment of a retinal detachment with a light beam (light coagulation) with a self-constructed device on the roof of the ophthalmic clinic at the University of Hamburg-Eppendorf.

Polish ophthalmology dates to the thirteenth century. The Polish Ophthalmological Society was founded in 1911. A representative leader was Adam Zamenhof (1888–1940), who introduced certain diagnostic, surgical, and nonsurgical eye-care procedures. He was executed by the German Nazis in 1940.

Zofia Falkowska (1915–93) head of the Faculty and Clinic of Ophthalmology in Warsaw from 1963 to 1976, was the first to use lasers in her practice.

Contributions by Physicists

The prominent physicists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries includedErnst Abbe

Ernst Karl Abbe HonFRMS (23 January 1840 – 14 January 1905) was a German physicist, optical scientist, entrepreneur, and social reformer. Together with Otto Schott and Carl Zeiss, he developed numerous optical instruments. He was also a c ...

(1840–1905), a co-owner of at the Zeiss Jena factories in Germany, where he developed numerous optical instruments. Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associatio ...

(1821-1894) was a polymath who made contributions to many fields of science and invented the ophthalmoscope

Ophthalmoscopy, also called funduscopy, is a test that allows a health professional to see inside the fundus of the eye and other structures using an ophthalmoscope (or funduscope). It is done as part of an eye examination and may be done as part ...

in 1851. They both made theoretical calculations on image formation in optical systems and also had studied the optics of the eye.

Professional requirements

Ophthalmologists are physicians ( MD/DO in the U.S. or MBBS in the UK and elsewhere or DO/DOMS/DNB, who typically complete an undergraduate degree, general medical school, followed by a residency in ophthalmology. Ophthalmologists typically perform optical, medical and surgical eye care.Australia and New Zealand

In Australia andNew Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, the FRACO or FRANZCO is the equivalent postgraduate specialist qualification. The structured training system takes place over five years of postgraduate training. Overseas-trained ophthalmologists are assessed using the pathway published on the RANZCO website. Those who have completed their formal training in the UK and have the CCST or CCT, usually are deemed to be comparable.

Bangladesh

InBangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

to be an ophthalmologist the basic degree is an MBBS. Then they have to obtain a postgraduate degree or diploma in an ophthalmology specialty. In Bangladesh, these are diploma in ophthalmology, diploma in community ophthalmology, fellow or member of the College of Physicians and Surgeons in ophthalmology, and Master of Science in ophthalmology.

Canada

InCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, after medical school an ophthalmology residency is undertaken. The residency typically lasts five years, which culminates in fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of Canada (FRCSC). Subspecialty training is undertaken by approximately 30% of fellows (FRCSC) in a variety of fields from anterior segment, cornea, glaucoma, vision rehabilitation Vision rehabilitation (often called vision rehab) is a term for a medical rehabilitation to improve vision or low vision. In other words, it is the process of restoring functional ability and improving quality of life and independence in an indivi ...

, uveitis

Uveitis () is inflammation of the uvea, the pigmented layer of the eye between the inner retina and the outer fibrous layer composed of the sclera and cornea. The uvea consists of the middle layer of pigmented vascular structures of the eye and in ...

, oculoplastics, medical and surgical retina, ocular oncology

Eye neoplasms can affect all parts of the eye, and can be a benign tumor or a malignant tumor (cancer). Eye cancers can be primary (starts within the eye) or metastatic cancer (spread to the eye from another organ). The two most common cancers t ...

, Ocular pathology, or neuro-ophthalmology

Neuro-ophthalmology is an academically-oriented subspecialty that merges the fields of neurology and ophthalmology, often dealing with complex systemic diseases that have manifestations in the visual system. Neuro-ophthalmologists initially complet ...

. Approximately 35 vacancies open per year for ophthalmology residency training in all of Canada. These numbers fluctuate per year, ranging from 30 to 37 spots. Of these, up to ten spots are at French-speaking universities in Quebec. At the end of the five years, the graduating ophthalmologist must pass the oral and written portions of the Royal College exam in either English or French.

India

InIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, after completing MBBS degree, postgraduate study in ophthalmology is required. The degrees are doctor of medicine, master of surgery, diploma in ophthalmic medicine and surgery, and diplomate of national board. The concurrent training and work experience are in the form of a junior residency at a medical college, eye hospital, or institution under the supervision of experienced faculty. Further work experience in the form of fellowship, registrar, or senior resident refines the skills of these eye surgeons. All members of the India Ophthalmologist Society and various state-level ophthalmologist societies hold regular conferences and actively promote continuing medical education.

Nepal

InNepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

, to become an ophthalmologist, three years of postgraduate study is required after completing an MBBS degree. The postgraduate degree in ophthalmology is called medical doctor in ophthalmology. Currently, this degree is provided by Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, Tilganga, Kathmandu, BPKLCO, Institute of Medicine, TU, Kathmandu, BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Kathmandu University, Dhulikhel, and National Academy of Medical Science, Kathmandu. A few Nepalese citizens also study this subject in Bangladesh, China, India, Pakistan, and other countries. All graduates have to pass the Nepal Medical Council Licensing Exam to become a registered ophthalmologists in Nepal. The concurrent residency training is in the form of a PG student (resident) at a medical college, eye hospital, or institution according to the degree providing university's rules and regulations. Nepal Ophthalmic Society holds regular conferences and actively promotes continuing medical education.

Ireland

InIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland grants membership (MRCSI (Ophth)) and fellowship (FRCSI (Ophth)) qualifications in conjunction with the Irish College of Ophthalmologists. Total postgraduate training involves an intern year, a minimum of three years of basic surgical training, and a further 4.5 years of higher surgical training. Clinical training takes place within public, Health Service Executive

The Health Service Executive (HSE) ( ga, Feidhmeannacht na Seirbhíse Sláinte) is the publicly funded healthcare system in Ireland, responsible for the provision of health and personal social services. It came into operation on 1 January 2005 ...

-funded hospitals in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

, Sligo, Limerick, Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a city in the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay, and is the sixth most populous city on ...

, Waterford, and Cork. A minimum of 8.5 years of training is required before eligibility to work in consultant posts. Some trainees take extra time to obtain MSc, MD or PhD degrees and to undertake clinical fellowships in the UK, Australia, and the United States.

Pakistan

InPakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, after MBBS, a four-year full-time residency program leads to an exit-level FCPS examination in ophthalmology, held under the auspices of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Pakistan. The tough examination is assessed by both highly qualified Pakistani and eminent international ophthalmic consultants. As a prerequisite to the final examinations, an intermediate module, an optics and refraction module, and a dissertation written on a research project carried out under supervision is also assessed.

Moreover, a two-and-a-half-year residency program leads to an MCPS while a two-year training of DOMS is also being offered. For candidates in the military, a stringent two-year graded course, with quarterly assessments, is held under Armed Forces Post Graduate Medical Institute in Rawalpindi.

The M.S. in ophthalmology is also one of the specialty programs. In addition to programs for physicians, various diplomas and degrees for allied eyecare personnel are also being offered to produce competent optometrists, orthoptists, ophthalmic nurses, ophthalmic technologists, and ophthalmic technicians in this field. These programs are being offered, notably by the College of Ophthalmology and Allied Vision Sciences, in Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is the capital of the province of Punjab where it is the largest city ...

and the Pakistan Institute of Community Ophthalmology in Peshawar. Subspecialty fellowships also are being offered in the fields of pediatric ophthalmology and vitreoretinal ophthalmology. King Edward Medical University, Al Shifa Trust Eye Hospital Rawalpindi, and Al- Ibrahim Eye Hospital Karachi also have started a degree program in this field.

Philippines

In the Philippines, Ophthalmology is considered a medical specialty that uses medicine and surgery to treat diseases of the eye. There is only one professional organization in the country that is duly recognized by the PMA and the PCS: the Philippine Academy of Ophthalmology (PAO). PAO and the state-standard Philippine Board of Ophthalmology (PBO) regulates ophthalmology residency programs and board certification. To become a general ophthalmologist in the Philippines, a candidate must have completed a doctor of medicine degree (MD) or its equivalent (e.g. MBBS), have completed an internship in Medicine, have passed the physician licensure exam, and have completed residency training at a hospital accredited by the Philippine Board of Ophthalmology (accrediting arm of PAO). Attainment of board certification in ophthalmology from the PBO is essential in acquiring privileges in most major health institutions. Graduates of residency programs can receive further training in ophthalmology subspecialties, such as neuro-ophthalmology, retina, etc. by completing a fellowship program that varies in length depending on each program's requirements.United Kingdom

In theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, three colleges grant postgraduate degrees in ophthalmology. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) and the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

grant MRCOphth/FRCOphth and MRCSEd/FRCSEd, (although membership is no longer a prerequisite for fellowship), the Royal College of Glasgow grants FRCS. Postgraduate work as a specialist registrar

A specialist registrar (SpR) is a doctor in the United Kingdom or the Republic of Ireland who is receiving advanced training in a specialist field of medicine in order to become a consultant in that specialty.

After graduation from medical school ...

and one of these degrees is required for specialization in eye disease

This is a partial list of human eye diseases and disorders.

The World Health Organization publishes a classification of known diseases and injuries, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, or ICD-10. ...

s. Such clinical work is within the NHS, with supplementary private work for some consultants.

Only 2.3 ophthalmologists exist per 100,000 population in the UK – fewer ''pro rata'' than in any nations in the European Union.

United States

Ophthalmologists typically complete four years of undergraduate studies, four years of medical school and four years of eye-specific training (residency). Some pursue additional training, known as a fellowship - typically one to two years. Ophthalmologists are physicians who specialize in the eye and related structures. They perform medical and surgical eye care and may also write prescriptions for corrective lenses. They often manage late stage eye disease, which typically involves surgery.

Ophthalmologists must complete the requirements of continuing medical education to maintain licensure and for recertification.

Ophthalmologists typically complete four years of undergraduate studies, four years of medical school and four years of eye-specific training (residency). Some pursue additional training, known as a fellowship - typically one to two years. Ophthalmologists are physicians who specialize in the eye and related structures. They perform medical and surgical eye care and may also write prescriptions for corrective lenses. They often manage late stage eye disease, which typically involves surgery.

Ophthalmologists must complete the requirements of continuing medical education to maintain licensure and for recertification.

Notable ophthalmologists

The following is a list of physicians who have significantly contributed to the field of ophthalmology:18th–19th centuries

* Theodor Leber (1840–1917) discovered Leber's congenital amaurosis, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, Leber's miliary aneurysm, and Leber's stellate neuroretinitis * Carl Ferdinand von Arlt (1812–1887), the elder (Austrian), proved that myopia is largely due to an excessive axial length, published influential textbooks on eye disease, and ran annual eye clinics in needy areas long before the concept of volunteer eye camps became popular; his name is still attached to some disease signs, e.g., vonArlt's line

Arlt's line is a thick band of scar tissue in the conjunctiva of the eye, near the lid margin, that is associated with eye infections. Arlt's line is a characteristic finding of trachoma, an infection of the eye caused by ''Chlamydia trachomatis ...

in trachoma and his son, Ferdinand Ritter von Arlt, the younger, was also an ophthalmologist

* Jacques Daviel (1696–1762) (France) claimed to be the founder of modern cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

surgery in that he performed cataract extraction instead of needling the cataract or pushing it back into the vitreous; he is said to have carried out the technique on 206 patients in 1752–53, of which 182 were reported to be successful, however, these figures are not very credible, given the total lack of both anaesthesia and aseptic technique at that time

* Franciscus Donders (1818–1889) (Dutch) published pioneering analyses of ocular biomechanics, intraocular pressure, glaucoma, and physiological optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

and he made possible the prescribing of combinations of spherical and cylindrical lenses to treat astigmatism

Astigmatism is a type of refractive error due to rotational asymmetry in the eye's refractive power. This results in distorted or blurred vision at any distance. Other symptoms can include eyestrain, headaches, and trouble driving at n ...

* Joseph Forlenze

Joseph-Nicolas-Blaise Forlenze (born Giuseppe Nicolò Leonardo Biagio Forlenza, 3 February 1757 – 22 July 1833), was an Italian ophthalmologist and surgery, surgeon, considered one of the most important ophthalmologists between the 18th and the 1 ...

(1757–1833) (Italy), specialist in cataract surgery

Cataract surgery, also called lens replacement surgery, is the removal of the natural lens of the eye (also called "crystalline lens") that has developed an opacification, which is referred to as a cataract, and its replacement with an intra ...

, became popular during the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental E ...

, healing, among many, personalities such as the minister Jean-Étienne-Marie Portalis and the poet Ponce Denis Lebrun; he was nominated by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

"chirurgien oculiste of the lycees, the civil hospices and all the charitable institutions of the departments of the Empire", and he also was known for his free interventions, mainly in favour of poor people

* Albrecht von Graefe Albrecht von Graefe may refer to:

* Albrecht von Graefe (ophthalmologist) (1828-1870), Prussian opthalmologist

* Albrecht von Graefe (politician)

Albrecht von Graefe (1 January 1868 – 18 April 1933) was a German landowner and right-wing ...

(1828–1870) (Germany) probably the most important ophthalmologist of the nineteenth century, along with Helmholtz and Donders, one of the 'founding fathers' of ophthalmology as a specialty, he was a brilliant clinician and charismatic teacher who had an international influence on the development of ophthalmology, and was a pioneer in mapping visual field defects and diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma, and he introduced a cataract extraction technique that remained the standard for more than 100 years, and many other important surgical techniques such as iridectomy. He rationalised the use of many ophthalmically important drugs, including mydriatics and miotics; he also was the founder of one of the earliest ophthalmic societies (German Ophthalmological Society, 1857) and one of the earliest ophthalmic journals (''Graefe's Archives of Ophthalmology'')

* Allvar Gullstrand (1862–1930) (Sweden) was a

* Allvar Gullstrand (1862–1930) (Sweden) was a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

-winner in 1911 for his research on the eye as a light-refracting apparatus, he described the 'schematic eye', a mathematical model of the human eye based on his measurements known as the 'optical constants' of the eye; his measurements are still used today

* Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associatio ...

(1821–1894), a great German polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

, invented the ophthalmoscope (1851) and published important work on physiological optics, including colour vision.

* Julius Hirschberg (1843–1925) (Germany) in 1879 became the first to use an electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in ...

to remove metallic foreign bodies from the eye and in 1886 developed the Hirschberg test for measuring strabismus

Strabismus is a vision disorder in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. The eye that is focused on an object can alternate. The condition may be present occasionally or constantly. If present during a ...

* Peter Adolph Gad (1846 – 1907), Danish ophthalmologist who founded the first eye infirmary in São Paulo, Brazil

* Socrate Polara (1800–1860, Italy) founded the first dedicated ophthalmology clinic in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

in 1829, entirely as a philanthropic endeavor; later he was appointed as the first director of the ophthalmology department at the Grand Hospital of Palermo, Sicily, in 1831 after the Sicilian government became convinced of the importance of state support for the specialization

* Herman Snellen

Herman Snellen (February 19, 1834 – January 18, 1908) was a Dutch ophthalmologist who introduced the Snellen chart to study visual acuity (1862). He took over directorship of the Netherlands Hospital for Eye Patients (Nederlandsch Gasthuis vo ...

(1834–1908) (Netherlands) introduced the Snellen chart to study visual acuity

20th–21st centuries

* Vladimir Petrovich Filatov (1875–1956) (Ukraine) contributed the tube flap grafting method, corneal transplantation, and preservation of grafts from cadaver eyes and tissue therapy; he founded theFilatov Institute of Eye Diseases and Tissue Therapy

The Filatov Institute is a research institute and a large ophthalmology (eye) hospital in Odesa, Ukraine. It was founded by Vladimir Filatov, an academic ophthalmologist. Its mission is the study of eye diseases and injuries, the training of opht ...

, Odessa, one of the leading eye-care institutes in the world

* Shinobu Ishihara (1879-1963) (Japan), in 1918, invented the Ishihara Color Vision Test, a common method for determining Color blindness

Color blindness or color vision deficiency (CVD) is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. It can impair tasks such as selecting ripe fruit, choosing clothing, and reading traffic lights. Color blindness may make some aca ...

; he also made major contributions to the study of Trachoma

Trachoma is an infectious disease caused by bacterium '' Chlamydia trachomatis''. The infection causes a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids. This roughening can lead to pain in the eyes, breakdown of the outer surface or cornea of ...

and Myopia

* Ignacio Barraquer (1884–1965) (Spain), in 1917, invented the first motorized vacuum instrument (erisophake) for intracapsular cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

extraction; he founded the Barraquer Clinic in 1941 and the Barraquer Institute in 1947 in Barcelona, Spain

* Ernst Fuchs (1851-1930) was an Austrian ophthalmologist known for his discovery and description of numerous ocular diseases and abnormalities including Fuchs' dystrophy and Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis

Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI) is a chronic unilateral uveitis appearing with the triad of heterochromia, predisposition to cataract and glaucoma, and keratitic precipitates on the posterior corneal surface. Patients are often asymptomati ...

* Tsutomu Sato (1902-1960) (Japan) pioneer in incisional refractive surgery, including techniques for astigmatism and the invention of radial keratotomy for myopia

* Jules Gonin (1870–1935) (Switzerland) was the "father of retinal detachment surgery"

* Sir Harold Ridley (1906–2001) (United Kingdom), in 1949, may have been the first to successfully implant an artificial intraocular lens after observing that plastic fragments in the eyes of wartime pilots were well tolerated; he fought for decades against strong reactionary opinions to have the concept accepted as feasible and useful

* Charles Schepens

Charles Louis Schepens (March 13, 1912 – March 28, 2006) was an influential Belgian (later American) ophthalmologist, regarded by many in the profession as "the father of modern retinal surgery",American Academy of Ophthalmology2003 Laureate A ...

(1912–2006) (Belgium) was the "father of modern retinal surgery" and developer of the Schepens indirect binocular ophthalmoscope whilst at Moorfields Eye Hospital; he was the founder of the Schepens Eye Research Institute, associated with Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

* Tom Pashby (1915–2005) (Canada) was Canadian Standards Association and a sport safety advocate to prevent eye injuries and spinal cord injuries, developed safer sports equipment, named to the Order of Canada, inducted into Canada's Sport Hall of Fame

* Marshall M. Parks (1918–2005) was the "father of pediatric ophthalmology"

* José Ignacio Barraquer

José Ignacio Barraquer Moner (24 January 1916 – 13 February 1998) was a Spanish ophthalmologist and inventor born in Barcelona who did most of his life's work in Bogotá, Colombia.

His original pioneering investigations on corneal transpla ...

(1916–1998) (Spain) was the "father of modern refractive surgery" and in the 1960s, he developed lamellar techniques, including keratomileusis

Keratomileusis, from Greek κέρας (kéras: horn) and σμίλευσις (smíleusis: carving),The word is derived from Greek κέρας - keras (root: kerat-) "horn, cornea" and σμίλευσις - smileusis "carving or corneal reshaping, is ...

and keratophakia, as well as the first microkeratome

A microkeratome is a precision surgical instrument with an oscillating blade designed for creating the corneal flap in LASIK or ALK surgery. The normal human cornea varies from around 500 to 600 micrometres in thickness; and in the LASIK procedur ...

and corneal microlathe

* Tadeusz Krwawicz

Tadeusz Krwawicz (15 January 1910 – 17 August 1988) was a Polish ophthalmologist. He pioneered the use of cryosurgery in ophthalmology.A . Skłodowska, J. Szaflik.Tadeusz Krwawicz - Distinguished Ophthalmologist and Polish Scientist (1910-19 ...

(1910–1988) (Poland), in 1961, developed the first cryoprobe for intracapsular cataract extraction

* Svyatoslav Fyodorov

Svyatoslav Nikolayevich Fyodorov (; August 8, 1927 – June 2, 2000) was a Russian ophthalmologist, politician, professor, full member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. He is considered to be a pioneer o ...

(1927–2000) (Russia) was the "father of ophthalmic microsurgery" and he improved and popularized radial keratotomy, invented a surgical cure for cataract, and he developed scleroplasty

* Charles Kelman

Charles David Kelman (May 23, 1930June 1, 2004) was an American ophthalmologist, surgeon, inventor, jazz musician, entertainer, and Broadway producer. Known as the father of phacoemulsification, he developed many of the medical devices, instrume ...

(1930–2004)(United States) developed the ultrasound and mechanized irrigation and aspiration system for phacoemulsification

Phacoemulsification is a modern cataract surgery method in which the eye's internal lens is emulsified with an ultrasonic handpiece and aspirated from the eye. Aspirated fluids are replaced with irrigation of balanced salt solution to maintain ...

, first allowing cataract extraction through a small incision.

* Helena Ndume

Helena Ndaipovanhu Ndume () is a Namibian ophthalmologist, notable for her charitable work among sufferers of eye-related illnesses in Namibia. To date, Ndume has ensured that some 30,000 blind Namibians have received eye surgery and are fitted w ...

(b.1960) (Namibia) is a renowned ophthalmologist notable for her charitable work among people with eye-related illnesses.

See also

* ''Book of the Ten Treatises of the Eye

Hunayn ibn Ishaq's ''Book of the Ten Treatises of the Eye'' is a 9th-century theory of vision based upon the cosmological natures of pathways from the brain to the object being perceived. This ophthalmic composition is heavily derived from Gale ...

''

* Chinese ophthalmology

* Copiale cipher

* American Academy of Ophthalmology

* European Board of Ophthalmology

The European Board of Ophthalmology (EBO) is the European professional association for ophthalmology.

Founded in London in 1992, it is a specialised agency of the European Union of Medical Specialists

The European Union of Medical Specialists (U ...

* Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology

* EyeWiki

This is a list of medical wikis, collaboratively-editable websites that focus on medical information. Many of the most popular medical wikis take the form of encyclopedias, with a separate article for each medical term. Some of these websites, such ...

* Eye disease

This is a partial list of human eye diseases and disorders.

The World Health Organization publishes a classification of known diseases and injuries, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, or ICD-10. ...

* List of systemic diseases with ocular manifestations

* Eye surgery

* Optometry

* Orthoptics

Orthoptics is a profession allied to the eye care profession. Orthoptists are the experts in diagnosing and treating defects in eye movements and problems with how the eyes work together, called binocular vision. These can be caused by issues with ...

* Eye care professional

An eye care professional (ECP) is an individual who provides a service related to the eyes or vision. It is any healthcare worker involved in eye care, from one with a small amount of post-secondary training to practitioners with a doctoral level ...

References

External links

EyeWiki

Aaojournal

{{Authority control Surgical specialties