Old St. Paul's Cathedral on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the

The finished cathedral of the Middle Ages was renowned for the beauty of its interior. Canon William Benham wrote in 1902: "It had not a rival in England, perhaps one might say in Europe."

The

The finished cathedral of the Middle Ages was renowned for the beauty of its interior. Canon William Benham wrote in 1902: "It had not a rival in England, perhaps one might say in Europe."

The  Monarchs and other notables were often in attendance at the cathedral, and the court occasionally held sessions there.Benham, 36. The building was also the place of several incidents. In 1191, whilst

Monarchs and other notables were often in attendance at the cathedral, and the court occasionally held sessions there.Benham, 36. The building was also the place of several incidents. In 1191, whilst

The first historical reference to the nave, "Paul's walk", being used as a marketplace and general meeting area is recorded during the 1381–1404 tenure of Bishop Braybrooke. The bishop issued an open letter decrying the use of the building for selling "wares, as if it were a public market" and "others ... by the instigation of the Devil

The first historical reference to the nave, "Paul's walk", being used as a marketplace and general meeting area is recorded during the 1381–1404 tenure of Bishop Braybrooke. The bishop issued an open letter decrying the use of the building for selling "wares, as if it were a public market" and "others ... by the instigation of the Devil

By the 16th century the building was deteriorating. Under

By the 16th century the building was deteriorating. Under  Crowds were drawn to the northeast corner of the Churchyard,

Crowds were drawn to the northeast corner of the Churchyard,

On 4 June 1561, the spire caught fire and crashed through the nave roof. According to a newsheet published days after the fire, the cause was a lightning strike.Pollard, A. F., ed., ''Tudor Tracts'', (1903)

On 4 June 1561, the spire caught fire and crashed through the nave roof. According to a newsheet published days after the fire, the cause was a lightning strike.Pollard, A. F., ed., ''Tudor Tracts'', (1903)

pp. 401–407, from the contemporary newsheet; ''The True Report of the Burning of the Steeple and Church of St Pauls'', London (1561) In 1753, David Henry, a writer for ''

After the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II appointed Sir

After the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II appointed Sir

Temporary repairs were made to the building. While it might have been salvageable, albeit with almost complete reconstruction, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style instead, a step which had been contemplated even before the fire. Wren declared that it was impossible to restore the old building.Benham, 74–75.

The following April, the Dean

Temporary repairs were made to the building. While it might have been salvageable, albeit with almost complete reconstruction, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style instead, a step which had been contemplated even before the fire. Wren declared that it was impossible to restore the old building.Benham, 74–75.

The following April, the Dean

Official website

with history of Old St. Paul's

Virtual St Paul's Cathedral Project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Saint Pauls Cathedral, Old Buildings and structures completed in 1314 Pre-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals Churches in the City of London Demolished buildings and structures in London Former buildings and structures in the City of London Former cathedrals in London

cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

that, until the Great Fire of 1666

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

, the cathedral was perhaps the fourth church at Ludgate Hill

Ludgate Hill is a street and surrounding area, on a small hill in the City of London. The street passes through the former site of Ludgate, a city gate that was demolished – along with a gaol attached to it – in 1760.

The area include ...

.

Work on the cathedral began after a fire in 1087. Work took more than 200 years, and was delayed by another fire in 1135. The church was consecrated

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different gro ...

in 1240, enlarged in 1256 and again in the early 14th century. At its completion in the mid-14th century, the cathedral was one of the longest churches in the world, had one of the tallest spires and some of the finest stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

.

The presence of the shrine of Saint Erkenwald made the cathedral a site of pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

.Milman, 22. In addition to serving as the seat of the Diocese of London

The Diocese of London forms part of the Church of England's Province of Canterbury in England.

It lies directly north of the Thames. For centuries the diocese covered a vast tract and bordered the dioceses of Norwich and Lincoln to the nort ...

, the building developed a reputation as a social hub, with the nave aisle, "Paul's walk

Paul's walk in Elizabethan and early Stuart London was the name given to the central nave of Old St Paul's Cathedral, where people walked up and down in search of the latest news. At the time, St. Paul's was the centre of the London grapevin ...

", known as a business centre and a place to hear the gossip on the London grapevine

''Vitis'' (grapevine) is a genus of 79 accepted species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus is made up of species predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, ...

. After the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the open-air pulpit in the churchyard, St Paul's Cross

St Paul's Cross (alternative spellings – "Powles Crosse") was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit in the grounds of Old St Paul's Cathedral, City of London. It was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England, and ma ...

, became the place for radical evangelical preaching and Protestant bookselling

Bookselling is the commercial trading of books which is the retail and distribution end of the publishing process. People who engage in bookselling are called booksellers, bookdealers, bookpeople, bookmen, or bookwomen. The founding of librar ...

.

The cathedral was already in severe structural decline by the early 17th century. Restoration work begun by Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

in the 1620s was temporarily halted during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

(1642–1651). In 1666, further restoration was in progress under Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churche ...

when the cathedral was devastated in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

. At that point, it was demolished, and the present cathedral was built on the site.

Construction

Old St Paul's Cathedral was perhaps the fourth church atLudgate Hill

Ludgate Hill is a street and surrounding area, on a small hill in the City of London. The street passes through the former site of Ludgate, a city gate that was demolished – along with a gaol attached to it – in 1760.

The area include ...

dedicated to St Paul. A devastating fire in 1087, detailed in the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'', destroyed much of the cathedral. King William I (William the Conqueror) donated the stone from the destroyed Palatine Tower on the River Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. Its headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath, each of which was dammed into a series of ponds—the Hampstead Ponds an ...

towards the construction of a Romanesque Norman cathedral, an act sometimes said to be his last before death.

Bishop Maurice oversaw preparations, although it was primarily under his successor, Richard de Beaumis, that construction work fully commenced. Beaumis was assisted by King Henry I, who gave the bishop stone and asked that all material brought up the River Fleet for the cathedral should be free from toll. To fund the cathedral, Henry I gave Beaumis rights to all fish caught within the cathedral neighbourhood and tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

s on venison taken in the County of Essex. Beaumis also gave a site for the original foundation of St Paul's School.Benham, 4–5.

After Henry I's death, a civil war known as "The Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

" broke out. Henry of Blois

Henry of Blois ( c. 1096 8 August 1171), often known as Henry of Winchester, was Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey from 1126, and Bishop of Winchester from 1129 to his death. He was a younger son of Stephen Henry, Count of Blois by Adela of Normandy, ...

, Bishop of Winchester, was appointed to administer the affairs of St Paul's. Almost immediately, he had to deal with the aftermath of a fire at London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It re ...

in 1135. It spread over much of the city, damaging the cathedral and delaying its construction. During this period, the architectural style was changed from heavy Romanesque to Early English Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

. Although the base Norman columns were left alone, lancet pointed arches were placed over them in the triforium

A triforium is an interior gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, or it may be locat ...

and some heavy columns were substituted with clustered pillars. The steeple was erected in 1221 and the cathedral was rededicated by Bishop Roger Niger

Roger Niger (died 1241) was a thirteenth-century cleric who became Bishop of London. He is also known as Saint Roger of Beeleigh.

Life

In 1192 Niger was named a canon of St Paul's Cathedral, London, and he held the prebend of Ealdland in the d ...

in 1240.Benham, 5.

New work (1255–1314)

After a succession of storms, in 1255 Bishop Fulk Basset appealed for money to repair the roof. The roof was rebuilt in wood, which ultimately ruined the building. At this time, the east end of the cathedral church was lengthened, enclosing the parish church of St Faith, which was now brought within the cathedral. The eastward addition was referred to as "The New Work". After complaints from the dispossessed parishioners of St Faith's, the east end of the west crypt was allotted to them as their parish church. The congregation were also allowed to keep a detached tower with a peal of bells east of the church which had historically been used to peal the summons to theCheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, whe ...

Folkmote. The parish later moved to the Jesus chapel during the reign of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

and was merged with St Augustine Watling Street

St Augustine, Watling Street, was an Anglican church which stood just to the east of St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London. First recorded in the 12th century, it was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666 and rebuilt to the designs ...

after the 1666 fire.Reynolds, 194.

This "New Work" was completed in 1314, although the additions had been consecrated in 1300. Excavations in 1878 by Francis Penrose

Francis Cranmer Penrose FRS (29 October 1817 – 15 February 1903) was an English architect, archaeologist, astronomer and sportsman rower. He served as Surveyor of the Fabric of St Paul's Cathedral, and as President of the Royal Institute of ...

showed the enlarged cathedral was long (excluding the porch later added by Inigo Jones) and wide ( across the transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building with ...

s and crossing).Clifton-Taylor, 275.

The cathedral had one of Europe's tallest church spires, the height of which is traditionally given as , surpassing all but Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln Minster, or the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln and sometimes St Mary's Cathedral, in Lincoln, England, is a Grade I listed cathedral and is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Lincoln. Construc ...

. The King's Surveyor, Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

(1632–1723), judged that an overestimate and gave .Benham, 8. In 1664, Robert Hooke used a plumb-line to calculate the height of the tower as "two hundred and four feet very near, which is about sixty feet higher than it was usually reported to be." William Benham noted that the cathedral probably "resembled in general outline that of Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, but it was a hundred feet longer, and the spire was sixty or eighty feet higher. The tower was open internally as far as the base of the spire, and was probably more beautiful both inside and out than that of any other English cathedral."

Chapter house

According to the architectural historianJohn Harvey John Harvey may refer to:

People Academics

* John Harvey (astrologer) (1564–1592), English astrologer and physician

* John Harvey (architectural historian) (1911–1997), British architectural historian, who wrote on English Gothic architecture ...

, the octagonal chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole commun ...

, built about 1332 by William de Ramsey

William de Ramsey (fl. 1323 – died 1349) was an English Gothic master mason and architect who worked on and likely designed the two earliest buildings of the Perpendicular style of Gothic architecture. William Ramsey was likely an inventor of ...

, was the earliest example of Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-c ...

. This is confirmed by Alec Clifton-Taylor

Alec Clifton-Taylor (2 August 1907 – 1 April 1985) was an English architectural historian, writer and TV broadcaster.

Biography and works

Born Alec Clifton Taylor (no hyphen), the son of Stanley Edgar Taylor, corn-merchant, and Ethel Elizab ...

, who notes that the chapter house and St Stephen's Chapel at the medieval Westminster Palace

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

predate the early Perpendicular work at Gloucester Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinity, in Gloucester, England, stands in the north of the city near the River Severn. It originated with the establishment of a minster dedicated to ...

by several years. The foundations of the chapter house were recently made visible in the redeveloped south churchyard of the new cathedral.

Interior

The finished cathedral of the Middle Ages was renowned for the beauty of its interior. Canon William Benham wrote in 1902: "It had not a rival in England, perhaps one might say in Europe."

The

The finished cathedral of the Middle Ages was renowned for the beauty of its interior. Canon William Benham wrote in 1902: "It had not a rival in England, perhaps one might say in Europe."

The nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

's length was particularly notable, with a Norman triforium

A triforium is an interior gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, or it may be locat ...

and vaulted ceiling

In architecture, a vault (French ''voûte'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

. The length earned it the nickname "Paul's walk

Paul's walk in Elizabethan and early Stuart London was the name given to the central nave of Old St Paul's Cathedral, where people walked up and down in search of the latest news. At the time, St. Paul's was the centre of the London grapevin ...

". The cathedral's stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

was reputed to be the best in the country, and the east-end rose window

Rose window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in Gothic cathedrals and churches. The windows are divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The term ''rose window' ...

was particularly exquisite. The poet Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

used the windows as a metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide (or obscure) clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared wi ...

in "The Miller's Tale

"The Miller's Tale" ( enm, The Milleres Tale) is the second of Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales'' (1380s–1390s), told by the drunken miller Robin toquite (a Middle English term meaning requite or pay back, in both good and negative wa ...

" from ''The Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's '' magnum opus ...

'', knowing that other Londoners at that time would understand the comparison:

From the cathedral's construction until its destruction, the shrine of Erkenwald was a popular pilgrimage site.Webb, 29. Under Bishop Maurice, reports of miracles attributed to the shrine increased, with the shrine attracting thousands of pilgrims. The alliterative Middle English poem '' St Erkenwald'' (sometimes attributed to the 14th-century "Pearl Poet

The "Gawain Poet" (), or less commonly the "Pearl Poet",Andrew, M. "Theories of Authorship" (1997) in Brewer (ed). ''A Companion to the Gawain-poet'', Boydell & Brewer, p.23 (''fl.'' late 14th century) is the name given to the author of '' Sir ...

") begins with a description of the construction of the cathedral, referring to the building as the "New Werke".

The shrine was adorned with gold, silver and precious stones. In 1339, three London goldsmiths were employed for a whole year to rebuild the shrine to a higher standard. William Dugdale records that the shrine was pyramid

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilate ...

al in shape with an altar table placed in front for offerings.

Monarchs and other notables were often in attendance at the cathedral, and the court occasionally held sessions there.Benham, 36. The building was also the place of several incidents. In 1191, whilst

Monarchs and other notables were often in attendance at the cathedral, and the court occasionally held sessions there.Benham, 36. The building was also the place of several incidents. In 1191, whilst King Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ove ...

was in Palestine, his brother John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

summoned a council of bishops to St Paul's to denounce William de Longchamp

William de Longchamp (died 1197) was a medieval Lord Chancellor, Chief Justiciar, and Bishop of Ely in England. Born to a humble family in Normandy, he owed his advancement to royal favour. Although contemporary writers accused Longchamp's fa ...

, Bishop of Ely – to whom Richard had entrusted government affairs – for treason.

Later that year, William Fitz Osbern gave a speech against the oppression of the poor at Paul's Cross and incited a riot which saw the cathedral invaded, halted by a plea from Hubert Walter

Hubert Walter ( – 13 July 1205) was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor. As chancellor, Walter be ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury. Osbern barricaded himself in St Mary-le-Bow

The Church of St Mary-le-Bow is a Church of England parish church in the City of London. Located on Cheapside, one of the city's oldest and most important thoroughfares, the church was founded in 1080 by Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury. Rebuil ...

and was executed, after which Paul's Cross was silent for many years.

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Arthur, Prince of Wales (19/20 September 1486 – 2 April 1502), was the eldest son of King Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of York. He was Duke of Cornwall from birth, and he was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester in 1489. A ...

, son of Henry VII, married Catharine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

in St Paul's on 14 November 1501. Chroniclers are profuse in their descriptions of the decorations of the cathedral and city on that occasion. Arthur died five months later, at the age of 15, and the marriage was later proved contentious during the reign of his brother, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

.

Several kings of the Middle Ages lay in state in St Paul's before their funerals at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, including Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father ...

, Henry VI and Henry VII. In the case of Richard II, the display of his body in such a public place was to dispel rumours that he was not dead. The walls were lined with the tombs of bishops and nobility. In addition to the shrine of Erkenwald, two Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

kings were buried inside: Sebbi, King of the East Saxons, and Æthelred the Unready

Æthelred II ( ang, Æþelræd, ;Different spellings of this king’s name most commonly found in modern texts are "Ethelred" and "Æthelred" (or "Aethelred"), the latter being closer to the original Old English form . Compare the modern diale ...

.

A number of figures such as John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

and John de Beauchamp, 1st Baron Beauchamp de Warwick had particularly large monuments constructed within the cathedral, and the building later contained the tombs of the Crown minister Nicholas Bacon, Sir Philip Sidney, and John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's Cathe ...

. Donne's monument survived the 1666 fire, and is on display in the present building.

Paul's Walk

The first historical reference to the nave, "Paul's walk", being used as a marketplace and general meeting area is recorded during the 1381–1404 tenure of Bishop Braybrooke. The bishop issued an open letter decrying the use of the building for selling "wares, as if it were a public market" and "others ... by the instigation of the Devil

The first historical reference to the nave, "Paul's walk", being used as a marketplace and general meeting area is recorded during the 1381–1404 tenure of Bishop Braybrooke. The bishop issued an open letter decrying the use of the building for selling "wares, as if it were a public market" and "others ... by the instigation of the Devil sing

Singing is the act of creating musical sounds with the voice. A person who sings is called a singer, artist or vocalist (in jazz and/or popular music). Singers perform music (arias, recitatives, songs, etc.) that can be sung with or without ...

stones and arrows to bring down the birds, jackdaws and pigeons which nestle in the walls and crevices of the building. Others play at ball ... breaking the beautiful and costly painted windows to the amazement of spectators." His decree goes on to threaten perpetrators with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

.

By the 15th century, the cathedral had become the centre of the London grapevine

''Vitis'' (grapevine) is a genus of 79 accepted species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus is made up of species predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, ...

. "News mongers", as they were called, gathered there to pass on the latest news and gossip. Those who visited the cathedral to keep up with the news were known as "Paul's walkers".

According to Francis Osborne

Francis Osborne (26 September 1593 – 4 February 1659) was an English essayist, known for his '' Advice to a Son'', which became a very popular book soon after the English Restoration.

Life

He was born, according to his epitaph, on 26 Sept. 1 ...

(1593–1659):

It was the fashion of those times ... for the principal gentry, lords, courtiers, and men of all professions not merely mechanic, to meet in Paul's Church by eleven and walk in the middle aisle till twelve, and after dinner from three to six, during which times some discoursed on business, others of news. Now in regard of the universal there happened little that did not first or last arrive here ... And those news-mongers, as they called them, did not only take the boldness to weigh the public but most intrinsic actions of the state, which some courtier or other did betray to this society.St Paul's became the place to go to hear the latest news of current affairs, war, religion, parliament and the court. In his play ''Englishmen for my Money'', William Haughton (d. 1605) described Paul's walk as a kind of "open house" filled with a "great store of company that do nothing but go up and down, and go up and down, and make a grumbling together". Infested with beggars and thieves, Paul's walk was also a place to pick up gossip, topical jokes, and even prostitutes. In his ''Microcosmographie'' (1628), a series of satirical portraits of contemporary England, John Earle (1601–1665), described it thus:

aul's walkis the land's epitome, or you may call it the lesser isle of Great Britain. It is more than this, the whole world's map, which you may here discern in its perfectest motion, justling and turning. It is a heap of stones and men, with a vast confusion of languages; and were the steeple not sanctified, nothing liker Babel. The noise in it is like that of bees, a strange humming or buzz mixed of walking tongues and feet: it is a kind of still roar or loud whisper ... It is the great exchange of all discourse, and no business whatsoever but is here stirring and a-foot ... It is the general mint of all famous lies, which are here like the legends of popery, first coined and stamped in the church.

Decline (16th century)

By the 16th century the building was deteriorating. Under

By the 16th century the building was deteriorating. Under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

, the Dissolution of the Monasteries and Chantries Acts led to the destruction of interior ornamentation and the cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against ...

s, charnels, crypt

A crypt (from Latin '' crypta'' " vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, sarcophagi, or religious relics.

Originally, crypts were typically found below the main apse of a c ...

s, chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type ...

s, shrine

A shrine ( la, scrinium "case or chest for books or papers"; Old French: ''escrin'' "box or case") is a sacred or holy space dedicated to a specific deity, ancestor, hero, martyr, saint, daemon, or similar figure of respect, wherein they ...

s, chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

and other buildings in the churchyard.Chambers, 135–136.

Many of these former religious sites in St Paul's Churchyard

St Paul's Churchyard is an area immediately around St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London. It included St Paul's Cross and Paternoster Row. It became one of the principal marketplaces in London. St Paul's Cross was an open-air pulpit from whi ...

, having been seized by the crown, were sold as shops and rental properties, especially to printers and bookseller

Bookselling is the commercial trading of books which is the retail and distribution end of the publishing process. People who engage in bookselling are called booksellers, bookdealers, bookpeople, bookmen, or bookwomen. The founding of libra ...

s, such as Thomas Adams, who were often Protestants

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. Buildings that were razed often supplied ready-dressed building material for construction projects, such as the Lord Protector's city palace, Somerset House

Somerset House is a large Neoclassical complex situated on the south side of the Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadrangle was built on the site of a Tudor palace ("O ...

. Crowds were drawn to the northeast corner of the Churchyard,

Crowds were drawn to the northeast corner of the Churchyard, St Paul's Cross

St Paul's Cross (alternative spellings – "Powles Crosse") was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit in the grounds of Old St Paul's Cathedral, City of London. It was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England, and ma ...

, where open-air preaching took place. It was there in the Cross Yard in 1549 that radical Protestant preachers incited a mob to destroy many of the cathedral's interior decorations. In 1554, in an attempt to end inappropriate practices taking place in the nave, the Lord Mayor decreed that the church should return to its original purpose as a religious building, issuing a writ stating that the selling of horses, beer and "other gross wares" was "to the great dishonour and displeasure of Almighty God, and the great grief also and offence of all good and well-disposed persons".

Spire collapse (1561)

On 4 June 1561, the spire caught fire and crashed through the nave roof. According to a newsheet published days after the fire, the cause was a lightning strike.Pollard, A. F., ed., ''Tudor Tracts'', (1903)

On 4 June 1561, the spire caught fire and crashed through the nave roof. According to a newsheet published days after the fire, the cause was a lightning strike.Pollard, A. F., ed., ''Tudor Tracts'', (1903)pp. 401–407, from the contemporary newsheet; ''The True Report of the Burning of the Steeple and Church of St Pauls'', London (1561) In 1753, David Henry, a writer for ''

The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term '' magazine'' (from the French ''magazine' ...

'', revived a rumour in his ''Historical description of St. Paul's Cathedral,'' writing that a plumber had "confessed on his death bed" that he had "left a pan of coals and other fuel in the tower when he went to dinner." However, the number of contemporary eyewitnesses to the storm and a subsequent investigation appears to contradict this.

Whatever the cause, the subsequent conflagration was hot enough to melt the cathedral's bells and the lead covering the wooden spire "poured down like lava upon the roof", destroying it.Benham, 50. This event was taken by both Protestants and Catholics as a sign of God's displeasure at the other faction's actions. Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

contributed £1,000 in gold towards the cost of repairs as well as timber from the royal estate and the Bishop of London Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church dur ...

gave £1200, although the spire was never rebuilt. The repair work on the nave roof was sub-standard, and only fifty years after the rebuilding was in a dangerous condition.

Restoration work (1621–1666)

Concerned at the decaying state of the building,King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

appointed the classical architect Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

to restore the building. The poet Henry Farley records the king comparing himself to the building at the commencement of the work in 1621: "''I'' have had more sweeping, brushing and cleaning than in forty years before. My workmen looke like him they call Muldsacke after sweeping of a chimney."

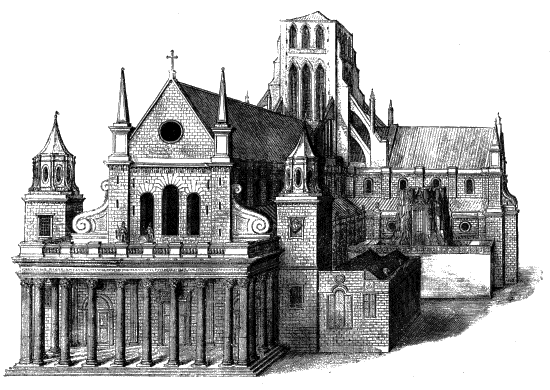

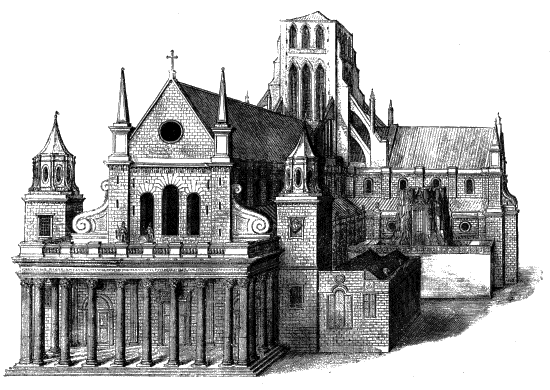

In addition to cleaning and rebuilding parts of the Gothic structure, Jones added a classical-style portico to the cathedral's west front in the 1630s, which William Benham notes was "altogether incongruous with the old building ... It was no doubt fortunate that Inigo Jones confined his work at St Paul's to some very poor additions to the transepts, and to a portico, very magnificent in its way, at the west end."

Work stopped during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, and there was much defacement and mistreatment of the building by Parliamentarian forces during which old documents and charters were dispersed and destroyed, and the nave used as a stable for cavalry horses. Much of the detailed information historians have of the cathedral is taken from William Dugdale

Sir William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) was an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject.

Life

Dugdale was born at Shustoke, near Coles ...

's 1658 ''History of St Pauls Cathedral'', written hastily during The Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, refers to the period from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659 during which England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and associated territories were joined together in the Co ...

for fear that "one of the most eminent Structures of that kinde in the Christian World" might be destroyed.

Indeed, a persistent rumour of the time suggested that Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

had considered giving the building to London's returning Jewish community to become a synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of wor ...

. Dugdale embarked on his project due to discovering hampers full of decaying 14th and 15th century documents from the cathedral's early archives. In his book's dedicatory epistle, he wrote:

... so great was your foresight of what we have since by wofull experience seen and felt, and specially in the Church, (through theDugdale's book is also the source for many of the surviving engravings of the building, created byPresbyterian Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...contagion, which then began violently to breake out) that you often and earnestly incited me to a speedy view of what Monuments I could, especially in the principall Churches of this Realme; to the end, that by Inke and paper, the Shadows of them, with their Inscriptions might be preserved for posteritie, forasmuch as the things themselves were so neer unto ruine.

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n etcher

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

Wenceslaus Hollar

Wenceslaus Hollar (23 July 1607 – 25 March 1677) was a prolific and accomplished Bohemian graphic artist of the 17th century, who spent much of his life in England. He is known to German speakers as ; and to Czech speakers as . He is particu ...

. In July 2010, an original sketch for Hollar's engravings was rediscovered when it was submitted to Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

auction house.

Great Fire of London (1666)

After the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II appointed Sir

After the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II appointed Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

to the position of Surveyor to the King's Works. He was given the task of restoring the cathedral in a style matching Inigo Jones' classical additions of 1630. Wren instead recommended that the building be completely demolished; according to his first biographer, James Elmes

James Elmes (15 October 1782, London – 2 April 1862, Greenwich) was an English architect, civil engineer, and writer on the arts.

Biography

Elmes was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, and, after studying building under his father, and ar ...

, Wren “expressed his surprise at the carelessness and want of accuracy in the original builders of the structure”; Wren's son described the new design as "The Gothic rectified to a better manner of architecture".

Both the clergy and citizens of the city opposed such a move.Cassell, 605. In response, Wren proposed to restore the body of the gothic building, but replace the existing tower with a dome. He wrote in his 1666 ''Of the Surveyor's Design for repairing the old ruinous structure of St Paul's'':

It must be concluded that the Tower from Top to Bottom and the adjacent parts are such a heap of deformaties that no Judicious Architect will think it corrigible by any Expense that can be laid out upon new dressing it.Clifton-Taylor, 237.Wren, whose uncle

Matthew Wren

Matthew Wren (3 December 1585 – 24 April 1667) was an influential English clergyman, bishop and scholar.

Life

He was the eldest son of Francis Wren (born 18 January 1552 at Newbold Revell), citizen and mercer of London, only son of Cuth ...

was Bishop of Ely, admired the central lantern of Ely Cathedral

Ely Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is an Anglican cathedral in the city of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England.

The cathedral has its origins in AD 672 when St Etheldreda built an abbey church. The present ...

and proposed that his dome design could be constructed over the top of the existing gothic tower, before the old structure was removed from within. This, he reasoned, would prevent the need for extensive scaffolding and would not upset Londoners ("Unbelievers") by demolishing a familiar landmark without being able to see its "hopeful Successor rise in its stead."van Eck, 155–160.

The matter was still under discussion when the restoration work on St Paul's finally began in the 1660s but soon after being sheathed in wooden scaffolding, the building was completely gutted in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

of 1666. The fire, aided by the scaffolding, destroyed the roof and much of the stonework along with masses of stocks and personal belongings that had been placed there for safety. Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

recalls the building in flames in his diary:

John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's diary, or m ...

's account paints a similar picture of destruction:

September 3rd – I went and saw the whole south part of the City burning from Cheapeside to the Thames, and ... was now taking hold of St. Paule's Church, to which the scaffolds contributed exceedingly.

September 7th – I went this morning on foote from White-hall as far as London Bridge, thro' the late Fleete-streete, Ludgate Hill, by St. Paules ... At my returne I was infinitely concern'd to find that goodly Church St. Paules now a sad ruine, and that beautiful portico ... now rent in pieces, flakes of vast stone split asunder, and nothing now remaining intire but the inscription in the architrave, shewing by whom it was built, which had not one letter of it defac'd. It was astonishing to see what immense stones the heate had in a manner calcin'd, so that all the ornaments, columns, freezes, capitals, and projectures of massie Portland-stone flew off, even to the very roofe, where a sheet of lead covering a great space (no less than six akers by measure) was totally mealted; the ruines of the vaulted roofe falling broke into St. Faith's, which being fill'd with the magazines of bookes belonging to the Stationers, and carried thither for safety, they were all consum'd, burning for a weeke following. It is also observable that the lead over the altar at the East end was untouch'd, and among the divers monuments, the body of one Bishop remain'd intire. Thus lay in ashes that most venerable Church, one of the most antient pieces of early piety in the Christian world.

Aftermath

Temporary repairs were made to the building. While it might have been salvageable, albeit with almost complete reconstruction, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style instead, a step which had been contemplated even before the fire. Wren declared that it was impossible to restore the old building.Benham, 74–75.

The following April, the Dean

Temporary repairs were made to the building. While it might have been salvageable, albeit with almost complete reconstruction, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style instead, a step which had been contemplated even before the fire. Wren declared that it was impossible to restore the old building.Benham, 74–75.

The following April, the Dean William Sancroft

William Sancroft (30 January 161724 November 1693) was the 79th Archbishop of Canterbury, and was one of the Seven Bishops imprisoned in 1688 for seditious libel against King James II, over his opposition to the king's Declaration of Indul ...

wrote to him that he had been right in his judgement: "Our work at the west end," he wrote, "has fallen about our ears." Two pillars had collapsed, and the rest was so unsafe that men were afraid to go near, even to pull it down. He added, "You are so absolutely necessary to us that we can do nothing, resolve on nothing without you."

Following this declaration by the Dean, demolition of the remains of the old cathedral began in 1668. Demolition of the Old Cathedral proved unexpectedly difficult as the stonework had been bonded together by molten lead. Wren initially used the then-new technique of using gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

to bring down the surviving stone walls. Like many experimental techniques, the use of gunpowder was not easy to control; several workers were killed and nearby residents complained about noise and damage. Eventually, Wren resorted to using a battering ram

A battering ram is a siege engine that originated in ancient times and was designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or splinter their wooden gates. In its simplest form, a battering ram is just a large, heavy log carried b ...

instead. Building work on the new cathedral began in June 1675.

Wren's first proposal, the "Greek cross" design, was considered too radical by members of a committee commissioned to rebuild the church. Members of the clergy decried the design as being too dissimilar from churches that already existed in England at the time to suggest any continuity within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

.Downes, 11–34. Wren's approved "Warrant design" sought to reconcile the Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

with his "better manner of architecture", featuring a portico influenced by Inigo Jones' addition to the old cathedral. However, Wren received permission from the king to make "ornamental changes" to the submitted design, and over the course of the construction made significant alterations, including the addition of the famous dome.

The topping out

In building construction, topping out (sometimes referred to as topping off) is a builders' rite traditionally held when the last beam (or its equivalent) is placed atop a structure during its construction. Nowadays, the ceremony is often parlaye ...

of the new cathedral took place in October 1708 and the cathedral was declared officially complete by Parliament in 1710. The consensus on the finished building was mixed; James Wright (1643–1713) wrote "Without, within, below, above the eye/ Is filled with unrestrained delight." Meanwhile, others were less approving, noting its similarity to St Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a Church (building), church built in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissanc ...

in Rome: "There was an air of Popery

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

about the gilded capitals, the heavy arches ... They were unfamiliar, un-English."

Notable burials in Old St Paul's

Nicholas Stone

Nicholas Stone (1586/87 – 24 August 1647) was an English sculptor and architect. In 1619 he was appointed master-mason to James I, and in 1626 to Charles I.

During his career he was the mason responsible for not only the building of ...

's 1631 monument to John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's Cathe ...

survived the fire. It depicts the poet, standing upon an urn, dressed in a winding cloth, rising for the moment of judgement. This depiction, Donne's own idea, was sculpted from a painting for which he posed.

No further memorials or tombs survive of the many famous people buried at Old St Paul's. In 1913 the letter-cutter MacDonald Gill and Mervyn MacCartney created a new tablet with the names of lost burials which was installed in Wren's cathedral:

See also

*List of demolished buildings and structures in London

This list of demolished buildings and structures in London includes buildings, structures and urban scenes of particular architectural and historical interest, scenic buildings which are preserved in old photographs, prints and paintings, but whic ...

* Montfichet's Tower

Montfichet's Tower (also known as Montfichet's Castle and/or spelt Mountfitchet's or Mountfiquit's) was a Norman fortress on Ludgate Hill in London, between where St Paul's Cathedral and City Thameslink railway station now stand. First docume ...

, a Norman fortress on Ludgate Hill in London.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Official website

with history of Old St. Paul's

Virtual St Paul's Cathedral Project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Saint Pauls Cathedral, Old Buildings and structures completed in 1314 Pre-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals Churches in the City of London Demolished buildings and structures in London Former buildings and structures in the City of London Former cathedrals in London

Old

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

*Old, Northamptonshire, England

* Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, M ...

1314 establishments in England

1666 disestablishments in England