The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (;

Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

:

/otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of

Native American tribes and

First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on

language divisions: the

Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

and

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

; collectively they are known as the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ ("Seven Council Fires"). The term "Sioux" is an

exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group ...

created from a

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

transcription of the

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

term "Nadouessioux", and can refer to any ethnic group within the

Great Sioux Nation

The Great Sioux Nation is the traditional political structure of the Sioux in North America. The peoples who speak the Sioux language are considered to be members of the Oceti Sakowin (''Očhéthi Šakówiŋ'', pronounced ) or Seven Council Fire ...

or to any of the nation's many language dialects.

Before the 17th century, the

Santee Dakota

The Dakota (pronounced , Dakota language: ''Dakȟóta/Dakhóta'') are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided int ...

(; "Knife" also known as the Eastern Dakota) lived around

Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

with territories in present-day northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. They gathered

wild rice

Wild rice, also called manoomin, Canada rice, Indian rice, or water oats, is any of four species of grasses that form the genus ''Zizania'', and the grain that can be harvested from them. The grain was historically gathered and eaten in both ...

, hunted woodland animals and used canoes to fish. Wars with the

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

throughout the 1700s pushed the Dakota into southern Minnesota, where the Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) and Teton (Lakota) were residing. In the 1800s, the Dakota signed treaties with the United States, ceding much of their land in Minnesota. Failure of the United States to make treaty payments on time, as well as low food supplies, led to the

Dakota War of 1862, which resulted in the Dakota being exiled from Minnesota to numerous reservations in Nebraska, North and South Dakota and Canada. After 1870, the Dakota people began to return to Minnesota, creating the present-day reservations in the state. The Yankton and Yanktonai Dakota ( and ; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), collectively also referred to by the

endonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

, resided in the

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

area before ceding their land and moving to South Dakota in 1858. Despite ceding their lands, their treaty with the U.S. government allowed them to maintain their traditional role in the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ as the caretakers of the

Pipestone Quarry, which is the cultural center of the Sioux people. They are considered to be the Western Dakota (also called middle Sioux), and have in the past been erroneously classified as

Nakota

Nakota (or Nakoda or Nakona) is the endonym used by those ''Assiniboine'' Indigenous people in the US, and by the Stoney People, in Canada.

The Assiniboine branched off from the Great Sioux Nation (aka the ''Oceti Sakowin'') long ago and moved ...

. The actual Nakota are the

Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

and

Stoney

Stoney may refer to:

Places

* Stoney, Kansas, an unincorporated community in the United States

* Stoney Creek (disambiguation)

* Stoney Pond, a man-made lake located by Bucks Corners, New York

* Stoney (lunar crater)

* Stoney (Martian crater) ...

of

Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West or the Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a Canadian region that includes the four western provinces just north of the Canada� ...

and

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

.

The

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

, also called Teton (; possibly "dwellers on the prairie"), are the westernmost Sioux, known for their

hunting and warrior culture. With the arrival of the horse in the 1700s, the Lakota would become the most powerful tribe on the Plains by the 1850s. They fought the United States Army in the

Sioux Wars

The Sioux Wars were a series of conflicts between the United States and various subgroups of the Sioux people which occurred in the later half of the 19th century. The earliest conflict came in 1854 when a fight broke out at Fort Laramie in Wy ...

including defeating the

7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Irish air " Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated in some of the largest ba ...

at the

Battle of Little Big Horn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

. The armed conflicts with the U.S. ended with the

Wounded Knee Massacre.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the Dakota and Lakota would continue to fight for their

treaty rights

In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States the term treaty rights specifically refers to rights for indigenous peoples enumerated in treaties with settler societies that arose from European colonization.

Exactly who is indigenou ...

, including the

Wounded Knee incident

The Wounded Knee Occupation, also known as Second Wounded Knee, began on February 27, 1973, when approximately 200 Oglala Lakota (sometimes referred to as Oglala Sioux) and followers of the American Indian Movement (AIM) seized and occupie ...

,

Dakota Access Pipeline protests

The Dakota Access Pipeline Protests, also called by the hashtag # NoDAPL, began in April 2016 as a grassroots opposition to the construction of Energy Transfer Partners' Dakota Access Pipeline in the northern United States and ended on Fe ...

and the 1980

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

case, ''

United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians'', in which the court ruled that tribal lands covered under the

Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also the Sioux Treaty of 1868) is an agreement between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota and Arapaho Nation, following the failure of the first Fo ...

had been taken illegally by the US government, and the tribe was owed compensation plus interest. As of 2018, this amounted to more than $1 billion; the Sioux have refused the payment, demanding instead the

return of their land. Today, the Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations, communities, and reserves in

North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, ...

,

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

,

Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

,

Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, and

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

in the United States; and

Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

, and southern

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

in Canada.

Culture

Etymology

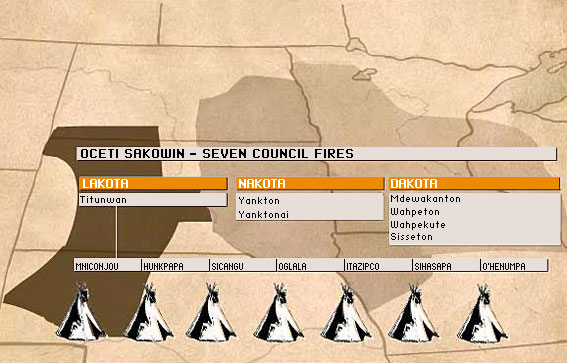

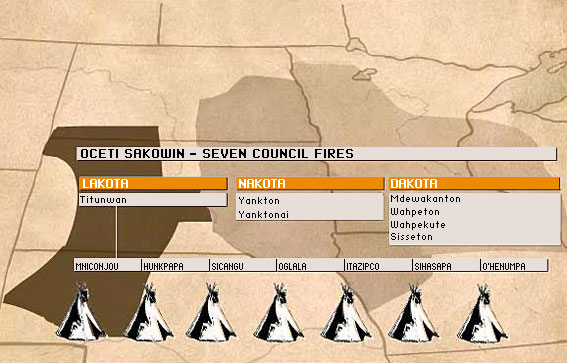

The Sioux people refer to their whole nation of people (sometimes called the Great Sioux Nation) as the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (pronounced , meaning "Seven Council Fires"). Each fire is a symbol of an oyate (people or nation). Today the seven nations that comprise the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ are the Thítȟuŋwaŋ (also known collectively as the Teton or Lakota), Bdewákaŋthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute, and Sisíthuŋwaŋ (also known collectively as the Santee or Eastern Dakota) and Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ and Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (also known collectively as the Yankton/Yanktonai or Western Dakota).

They are also referred to as the

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

or

Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

as based upon dialect differences.

In any of the dialects, Lakota or Dakota translates to mean "friend" or "ally" referring to the alliances between the bands.

The name "Sioux" was adopted in

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

by the 1760s from

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

. It is abbreviated from the French ''Nadouessioux'', first attested by

Jean Nicolet in 1640.

The name is sometimes said to be derived from "Nadowessi" (plural "Nadowessiwag"),

[NAA MS 4800 9 Three drafts of On the Comparative Phonology of Four Siouan Languages. James O. Dorsey papers, circa 1870-1956, bulk 1870-1895. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution] an

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group ...

for the Sioux meaning "little snakes" (compare ''nadowe'' "big snakes", used for the

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

). The French pluralized the Ojibwe singular "Nadowessi" by adding the French plural suffix "oux" to form "Nadowessioux," which was later shortened to "Sioux."

The

Proto-Algonquian

Proto-Algonquian (commonly abbreviated PA) is the proto-language from which the various Algonquian languages are descended. It is generally estimated to have been spoken around 2,500 to 3,000 years ago, but there is less agreement on where it was ...

form ''*na·towe·wa'', meaning "Northern Iroquoian", has reflexes in several daughter languages that refer to a small rattlesnake (

massasauga

The massasauga (''Sistrurus catenatus'') is a rattlesnake species found in midwestern North America from southern Ontario to northern Mexico and parts of the United States in between. Like all rattlesnakes, it is a pit viper and is venomous.

Th ...

, ''Sistrurus'').

An alternative explanation is derivation from an (Algonquian) exonym '' na·towe·ssiw'' (plural '' na·towe·ssiwak''), from a verb ''*-a·towe·'' meaning "to speak a foreign language".

The current Ojibwe term for the Sioux and related groups is ''Bwaanag'' (singular ''Bwaan''), meaning "roasters". Presumably, this refers to the style of cooking the Sioux used in the past.

In recent times, some of the tribes have formally or informally reclaimed traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sičháŋǧu Oyáte, and the Oglala often use the name Oglála Lakȟóta Oyáte, rather than the English Oglala Sioux Tribe or OST. The alternative English spelling of Ogallala is considered improper.

Traditional social structure

The traditional social structure of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ strongly relied on kinship ties that extend beyond human interaction and includes the natural and supernatural worlds.

("all are related") represents a spiritual belief of how human beings should ideally act and relate to other humans, the natural world, the spiritual world, and to the cosmos.

The thiyóšpaye represents the political and economic structure of traditional society.

Thiyóšpaye (community) kinship

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the different Očhéthi Šakówiŋ villages (oyáte, "tribe/nation") consisted of many thiyóšpaye ("camp circles"), which were large extended families united by kinship (thiwáhe, "immediate family").

Thiyóšpaye varied in size, were led by a leader appointed by an elder council and were nicknamed after a prominent member or memorable event associated with the band. Dakota ethnographer

Ella Cara Deloria

Ella Cara Deloria (January 31, 1889 – February 12, 1971), also called ''Aŋpétu Wašté Wiŋ'' (Beautiful Day Woman), was a Yankton Dakota (Sioux) educator, anthropologist, ethnographer, linguist, and novelist. She recorded Native American ...

noted the kinship ties were all-important, they dictated and demanded all phrases of traditional life:

During the

fur trade era, the thiyóšpaye refused to trade only for economic reasons. Instead the production and trade of goods was regulated by rules of kinship bonds.

Personal relationships were pivotal for success: in order for European-Americans to trade with the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, social bonds had to be created.

The most successful fur traders would marry into the kinship society, which also raised the status of the family of the woman through access to European goods.

Outsiders are also adopted into the kinship through the religious Huŋkalowaŋpi ceremony. Early European explorers and missionaries who lived among the Dakota were sometimes adopted into the thiyóšpaye (known as "huŋka relatives"), such as

Louis Hennepin

Father Louis Hennepin, O.F.M. baptized Antoine, (; 12 May 1626 – 5 December 1704) was a Belgian Roman Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Recollet order (French: ''Récollets'') and an explorer of the interior of North Ameri ...

who noted, "this help’d me to gain credit among these people".

During the later

reservation era, districts were often settled by clusters of families from the same thiyóšpaye.

Religion

The traditional social system extended beyond human interaction into the

supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

realms.

It is believed that

Wakȟáŋ Tháŋka ("Great Spirit/Great Mystery") created the universe and embodies everything in the universe as one.

The preeminent symbol of Sioux religion is the

Čhaŋgléska Wakȟaŋ ("sacred hoop"), which visually represents the concept that everything in the universe is intertwined.

The creation stories of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ describe how the

various spirits were formed from Wakȟáŋ Tháŋka.

Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950), was a ''wičháša wakȟáŋ'' (" medicine man, holy man") and '' heyoka'' of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and ...

describes the relationships with Wakȟáŋ Tháŋka as:

It is believed

prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deifie ...

is the act of invoking relationships with one's ancestors or spiritual world;

the Lakota word for prayer,

wočhékiye, means "to call on for aid," "to pray," and "to claim relationship with".

Their primary cultural prophet is Ptesáŋwiŋ,

White Buffalo Calf Woman

White Buffalo Calf Woman ('' Lakȟótiyapi'': ''Ptesáŋwiŋ'') or White Buffalo Maiden is a sacred woman of supernatural origin, central to the Lakota religion as the primary cultural prophet. Oral traditions relate that she brought the "Seven S ...

, who came as an intermediary between Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka and humankind to teach them how to be good relatives by introducing the Seven Sacred Rites and the

čhaŋnúŋpa (

sacred pipe).

The seven ceremonies are

Inípi (purification lodge), Haŋbléčheyapi (

crying for vision), Wiwáŋyaŋg Wačhípi (

Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individua ...

), Huŋkalowaŋpi (making of relatives), Išnáthi Awíčhalowaŋpi (female puberty ceremony), Tȟápa Waŋkáyeyapi (throwing of the ball) and Wanáǧi Yuhápi (soul keeping).

Each part of the čhaŋnúŋpa (stem, bowl, tobacco, breath, and smoke) is symbolic of the relationships of the natural world, the elements, humans and the spiritual beings that maintain the cycle of the universe.

Dreams can also be a means of establishing relationships with spirits and are of utmost importance to the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ.

One can gain supernatural powers through dreams; it is believed that dreaming of the

Wakíŋyaŋ

Wakíŋyaŋ is a Lakota word for "thunder." It also may be a portmanteau word

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of words (thunder beings) would make someone involuntarily a

Heyókȟa

The heyoka (, also spelled "haokah," "heyokha") is a kind of sacred clown in the culture of the Sioux (Lakota and Dakota people) of the Great Plains of North America. The heyoka is a contrarian, jester, and satirist, who speaks, moves and reacts ...

, a sacred clown.

Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950), was a ''wičháša wakȟáŋ'' (" medicine man, holy man") and '' heyoka'' of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and ...

, a famous Heyókȟa said: "Only those who have had visions of the thunder beings of the west can act as heyokas. They have sacred power and they share some of this with all the people, but they do it through funny actions".

Governance

Historical leadership organization

The thiyóšpaye of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ would assemble each summer to hold council, renew kinships, decide tribal matters, and participate in the

Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individua ...

.

The seven divisions would select four leaders known as Wičháša Yatápika from among the leaders of each division.

Being one of the four leaders was considered the highest honor for a leader; however, the annual gathering meant the majority of tribal administration was cared for by the usual leaders of each division. The last meeting of the Seven Council Fires was in 1850.

The historical political organization was based on individual participation and the cooperation of many to sustain the tribe's way of life. Leaders were chosen based upon noble birth and demonstrations of chiefly virtues, such as bravery, fortitude, generosity, and wisdom.

* Political leaders were members of the Načá Omníčiye society and decided matters of tribal hunts, camp movements, whether to make war or peace with their neighbors, or any other community action.

* Societies were similar to

fraternities

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity ...

; men joined to raise their position in the tribe. Societies were composed of smaller clans and varied in number among the seven divisions.

There were two types of societies: Akíčhita, for the younger men, and Načá, for elders and former leaders.

* Akíčhita (Warrior) societies existed to train warriors, hunters, and to police the community.

There were many smaller Akíčhita societies, including the Kit-Fox, Strong Heart, Elk, and so on.

* Leaders in the Načá societies, per Načá Omníčiye, were the tribal elders and leaders. They elected seven to ten men, depending on the division, each referred to as Wičháša Itȟáŋčhaŋ ("chief man"). Each Wičháša Itȟáŋčhaŋ interpreted and enforced the decisions of the Načá.

* The Wičháša Itȟáŋčhaŋ would elect two to four Shirt Wearers, who were the voice of the society. They settled quarrels among families and also foreign nations.

Shirt Wearers were often young men from families with hereditary claims of leadership. However, men with obscure parents who displayed outstanding leadership skills and had earned the respect of the community might also be elected.

Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by w ...

is an example of a common-born "Shirt Wearer".

* A Wakíčhuŋza ("Pipe Holder") ranked below the "Shirt Wearers". The Pipe Holders regulated peace ceremonies, selected camp locations, and supervised the Akíčhita societies during buffalo hunts.

Gender roles

Within the Sioux tribes, there were defined gender roles. The men in the village were tasked as the hunters, traveling outside the village.

The women within the village were in charge of making clothing and similar articles while also taking care of, and owning, the house.

However, even with these roles, both men and women held power in decision-making tasks and sexual preferences were flexible and allowed.

The term

wíŋtke would refer to men who partook in traditional feminine duties while the term witkówiŋ ("crazy woman") was used for women who rejected their roles as either mother or wife to be a prostitute.

Funeral practices

Traditional Funeral Practices

It is a common belief amongst Siouan communities that the spirit of the deceased travels to an

afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving es ...

. In traditional beliefs, this spiritual journey was believed to start once funeral proceedings were complete and spanned over a course of four days. Mourning family and friends would take part in that four-day

wake in order to accompany the spirit to its resting place.

In the past, bodies were not embalmed and put up on a

burial scaffold for one year before a ground burial. A platform to rest the body was put up on trees or, alternately, placed on four upright poles to elevate the body from the ground. The bodies would be securely wrapped in blankets and cloths, along with many of the deceased personal belongings and were always placed with their head pointed towards the south. Mourning individuals would speak to the body and offer food as if it were still alive. This practice, along with the

Ghost Dance

The Ghost Dance ( Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a ceremony incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka (renamed Jack Wil ...

helped individuals mourn and connect the spirits of the deceased with those who were alive.

[Mooney, James. ''The Ghost Dance Religion and Wounded Knee''. New York: Dover Publications; 1896] The only time a body was buried in the ground right after their death was if the individual was murdered: the deceased would be placed in the ground with their heads towards the south, while faced down along with a piece of fat in their mouth.

Contemporary Funeral Practices

According to Pat Janis, director of the

Oglala Sioux Tribe

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

’s Burial Assistance Program, funeral practices of communities today are often a mix of traditions and contemporary Christian practices. While tree burials and scaffold burials are not practiced anymore, it is also now rare to see families observe a four-day wake period. Instead, the families opt for one- or two-day wake periods which include a funeral feast for all the community. Added to the contemporary funeral practices, it is common to see prayers conducted by a medicine man along with traditional songs often sung with a drum. One member of the family is also required to be present next to the body at all times until the burial.

Gifts are placed within the casket to aid with the journey into the afterworld, which is still believed to take up to four days after death.

Music

History

Ancestral Sioux

The ancestral Sioux most likely lived in the Central Mississippi Valley region and later in Minnesota, for at least two or three thousand years.

The ancestors of the Sioux arrived in the northwoods of central Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin from the Central Mississippi River shortly before 800 AD.

Archaeologists refer to them as the Woodland Blackduck-Kathio-Clam River Continuum.

Around 1300 AD, they adopted the characteristics of a northern tribal society and became known as the Seven Council Fires.

First contact with Europeans

The Dakota are first recorded to have resided at the source of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

and the Great Lakes during the seventeenth century. They were dispersed west in 1659 due to warfare with the

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

. During the 1600s, the Lakota began their expansion westward into the Plains, taking with them the bulk of people of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ.

By 1700 the Dakota were living in

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

and

Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

. As the Sioux nation began expanding with access to horses, the Dakota were put in a weakened position to defend the eastern border: new diseases (smallpox and malaria) and increased intertribal warfare between the migration of tribes fleeing the Iroquois into their territory of present-day Wisconsin, put a strain on their ability to maintain their territory.

In the Mississippi valley, their population is believed to have declined by one-third between 1680 and 1805 due to those reasons.

French trade and intertribal warfare

Late in the 17th century, the Dakota entered into an alliance with French merchants. The French were trying to gain advantage in the struggle for the

North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the commercial trade in furs in North America. Various Indigenous peoples of the Americas traded furs with other tribes during the pre-Columbian era. Europeans started their participation in the North American fur ...

against the English, who had recently established the

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

. The

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

,

Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

and

Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

bands were among the first to trade with the French as they migrated into the Great Lakes region.

Upon their arrival, Dakota were in an economic alliance with them until the Dakota were able to trade directly for European goods with the French.

The first recorded encounter between the Sioux and the French occurred when

Radisson and

Groseilliers reached what is now Wisconsin during the winter of 1659–60. Later visiting French traders and missionaries included

Claude-Jean Allouez

Claude Jean Allouez (June 6, 1622 – August 28, 1689) was a Jesuit missionary and French explorer of North America. He established a number of missions among the indigenous people living near Lake Superior.

Biography

Allouez was born in Saint ...

,

Daniel Greysolon Duluth, and

Pierre-Charles Le Sueur

Pierre-Charles Le Sueur (c. 1657, Artois, France – 17 July 1704, Havana, Cuba) was a French fur trader and explorer in North America, recognized as the first known European to explore the Minnesota River valley.

Le Sueur came to Canada with ...

who wintered with Dakota bands in early 1700.

The Dakota began to resent the Ojibwe trading with the hereditary enemies of the Sioux, the

Cree

The Cree ( cr, néhinaw, script=Latn, , etc.; french: link=no, Cri) are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations.

In Canada, over 350,000 people are Cree o ...

and

Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

.

Tensions rose in the 1720s into a prolonged war in 1736.

The Dakota lost their traditional lands around

Leech Lake

Leech Lake is a lake located in north central Minnesota, United States. It is southeast of Bemidji, located mainly within the Leech Lake Indian Reservation, and completely within the Chippewa National Forest. It is used as a reservoir. The lake ...

and

Mille Lacs as they were forced south along the Mississippi River and St. Croix River Valley as a result of the battles.

These intertribal conflicts also made it dangerous for European fur traders: whichever side they traded with, they were viewed as enemies from the other.

For example, in 1736 a group of Sioux killed

Jean Baptiste de La Vérendrye and twenty other men on an island in

Lake of the Woods

Lake of the Woods (french: Lac des Bois, oj, Pikwedina Sagainan) is a lake occupying parts of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Manitoba and the U.S. state of Minnesota. Lake of the Woods is over long and wide, containing more than 14,5 ...

for such reasons.

However, trade with the French continued until the French gave up North America in 1763. Europeans repeatedly tried to make truce between the warring tribes in order to protect their interests.

One of the larger battles between the Dakota and Ojibwe took place in 1770 fought at the Dalles of the St. Croix. According to

William Whipple Warren

William Whipple Warren (May 27, 1825 – June 1, 1853) was a historian, interpreter, and legislator in the Minnesota Territory. The son of Lyman Marcus Warren, an American fur trader and Mary Cadotte, the Ojibwe-Metis daughter of fur trader ...

, a

Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Canadian Prairies, Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United State ...

historian, the fighting began when the

Meskwaki

The Meskwaki (sometimes spelled Mesquaki), also known by the European exonyms Fox Indians or the Fox, are a Native American people. They have been closely linked to the Sauk people of the same language family. In the Meskwaki language, th ...

(Fox) engaged the Ojibwe (their hereditary enemies) around

St. Croix Falls

St. Croix Falls is a city in Polk County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 2,208 at the 2020 census. The city is located within the Town of St. Croix Falls.

U.S. Route 8, Wisconsin Highway 35, and Wisconsin Highway 87 are three o ...

.

The Sioux were the former enemies of the Meskwaki and were enlisted to make a joint attack against the Ojibwe.

The Meskwaki were first to engage with the large Ojibwe war party led by

Waubojeeg: the Meskwaki allegedly boasted to the Dakota to hold back as they would make short work of their enemies. When the Dakota joined the battle, they had the upper hand until Sandy Lake Ojibwe reinforcements arrived.

The Dakota were driven back and Warren states: "Many were driven over the rocks into the boiling floods below, there to find a watery grave. Others, in attempting to jump into their narrow wooden canoes, were capsized into the rapids".

While Dakota and Ojibwe suffered heavy losses, the Meskwaki were left with the most dead and forced to join their relatives, the

Sauk people

The Sauk or Sac are a group of Native Americans of the Eastern Woodlands culture group, who lived primarily in the region of what is now Green Bay, Wisconsin, when first encountered by the French in 1667. Their autonym is oθaakiiwaki, and th ...

.

The victory for the Ojibwe secured control of the Upper St. Croix and created an informal boundary between the Dakota and Ojibwe around the mouth of the Snake River.

As the Lakota entered the prairies, they adopted many of the customs of the neighboring

Plains tribes

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of ...

, creating new cultural patterns based on the horse and fur trade.

Meanwhile, the Dakota retained many of their Woodlands features.

By 1803, the three divisions of the Sioux (Western/Eastern Dakota and Lakota) were established in their different environments and had developed their own distinctive lifeways.

However, due to the prevalent cultural concept of thiyóšpaye (community), the three divisions maintained strong ties throughout the changing times to present day.

Treaties and reservation period beginnings

In 1805, the Dakota signed their

first treaty with the American government.

Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

negotiated for 100,000 acres of land at the confluence of the

St. Croix River about what now is

Hastings, Minnesota

Hastings is a city mostly in Dakota County, Minnesota, of which it is the county seat, with a portion in Washington County, Minnesota. It is near the confluence of the Mississippi, Vermillion, and St. Croix Rivers. Its population was 22,154 ...

and the confluence of the

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

and

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

about what now is

St Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center ...

.

The Americans wanted to establish military outposts and the Dakota wanted a new source of trading. An American military post was not established at the confluence of the St. Croix with the Mississippi, but

Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

was established in 1819 along the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers.

In return, Dakota were promised the ability to "pass and repass, hunt, or make other uses of the said districts as they have formerly done".

In an attempt to stop intertribal warfare and to better able to negotiate with tribes, the American government signed the

1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien with the Dakota, Ojibwe, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Sac and Fox, Iowa, Potawatomi, and Ottawa tribes.

In the

1830 Treaty of Prairie de Chien, the Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) ceded their lands along the Des Moines river to the American government. Living in what is now southeastern South Dakota, the leaders of the Western Dakota signed the Treaty of April 19, 1858, which created the

Yankton Sioux Reservation. Pressured by the ongoing arrival of Europeans, Yankton chief

Struck by the Ree

Struck by the Ree, also known as Strikes the Ree (c. 1804–1888) was a chief of the Native American Yankton Sioux tribe.

Birth

In 1804, a great pow-wow was held for the Lewis and Clark Expedition at Calumet Bluff/Gavins Point (near present- ...

told his people, "The white men are coming in like maggots. It is useless to resist them. They are many more than we are. We could not hope to stop them. Many of our brave warriors would be killed, our women and children left in sorrow, and still we would not stop them. We must accept it, get the best terms we can get and try to adopt their ways."

Despite ceding their lands, the treaty allowed the Western Dakota to maintain their traditional role in the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ as the caretakers of the

Pipestone Quarry, which is the cultural center of the Sioux people.

With the creation of

Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Minnesota and west ...

by the United States in 1849, the Eastern Dakota (Sisseton, Wahpeton, Mdewakanton, and Wahpekute) people were pressured to cede more of their land. The reservation period for them began in 1851 with the signing of the

Treaty of Mendota

The Treaty of Mendota was signed in Mendota, Minnesota on August 5, 1851 between the United States federal government and the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Dakota people of Minnesota.

The agreement was signed near Pilot Knob on the south bank of the M ...

and the

Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux () was signed on July 23, 1851, at Traverse des Sioux in Minnesota Territory between the United States government and the Upper Dakota Sioux bands. In this land cession treaty, the Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota ban ...

.

The Treaty of Mendota was signed near Pilot Knob on the south bank of the

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

and within sight of

Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

. The treaty stipulated that the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands were to receive US$1,410,000 in return for relocating to the

Lower Sioux Agency

The Lower Sioux Agency, or Redwood Agency, was the federal administrative center for the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation in what became Redwood County, Minnesota, United States. It was the site of the Battle of Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 186 ...

on the

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

near present-day

Morton, Minnesota

Morton is a city in Renville County, Minnesota, United States. This city is ninety-five miles southwest of Minneapolis. It is the administrative headquarters of the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation. The population was 411 at the 2010 census.

H ...

along with giving up their rights to a significant portion of southern Minnesota.

In the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of the Dakota ceded 21 million acres for $1,665,000, or about 7.5 cents an acre.

However, the American government kept more than 80% of the funds with only the interest (5% for 50 years) being paid to the Dakota.

The US set aside two reservations for the Sioux along the

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

, each about wide and long. Later the government declared these were intended to be temporary, in an effort to force the Sioux out of Minnesota.

The

Upper Sioux Agency

Upper may refer to:

* Shoe upper or ''vamp'', the part of a shoe on the top of the foot

* Stimulant, drugs which induce temporary improvements in either mental or physical function or both

* ''Upper'', the original film title for the 2013 found fo ...

for the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands was established near

Granite Falls, Minnesota

Granite Falls is a city located mostly in Yellow Medicine County, Minnesota, of which it is the county seat with a small portion in Chippewa County, Minnesota. The population was 2,737 at the 2020 census. The Andrew John Volstead House, a Na ...

, while the

Lower Sioux Agency

The Lower Sioux Agency, or Redwood Agency, was the federal administrative center for the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation in what became Redwood County, Minnesota, United States. It was the site of the Battle of Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 186 ...

for the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands was established about thirty miles downstream near what developed as

Redwood Falls, Minnesota

Redwood Falls is a city in Redwood County, located along the Redwood River near its confluence with the Minnesota River, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. The population was 5,102 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat.

History

As the immig ...

. The Upper Sioux were not satisfied with their reservation because of low food supplies, but as it included several of their old villages, they agreed to stay. The Lower Sioux were displaced from their traditional woodlands and were dissatisfied with their new territory of mostly prairie.

The US intended the treaties to encourage the Sioux to convert from their nomadic hunting lifestyle into more European-American settled farming, offering them compensation in the transition. By 1858, the Dakota only had a small strip of land along the Minnesota River, with no access to their traditional hunting grounds.

They had to rely on treaty payments for their survival, which were often late.

The forced change in lifestyle and the much lower than expected payments from the federal government caused economic suffering and increased social tensions within the tribes. By 1862, many Dakota were starving and tensions erupted in the

Dakota War of 1862.

Dakota War of 1862 and the Dakota diaspora

By 1862, shortly after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Dakota. One trader,

Andrew Myrick

Andrew J. Myrick (May 28, 1832 – August 18, 1862) was a trader, who with his Dakota wife (''Winyangewin''/Nancy Myrick), operated stores in southwest Minnesota at two Native American agencies serving the Dakota (referred to as Sioux at the ti ...

, went so far as to say, "If they're hungry, let them eat grass."

On August 16, 1862, the treaty payments to the eastern Dakota arrived in

St. Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center o ...

, and were brought to

Fort Ridgely

Fort Ridgely was a frontier United States Army outpost from 1851 to 1867, built 1853–1854 in Minnesota Territory. The Sioux called it Esa Tonka. It was located overlooking the Minnesota river southwest of Fairfax, Minnesota. Half of the ...

the next day. However, they arrived too late to prevent the war. On August 17, 1862, the Dakota War began when a few Santee men murdered a white farmer and most of his family. They inspired further attacks on white settlements along the

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River ( dak, Mnísota Wakpá) is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It ris ...

. On August 18, 1862,

Little Crow of the Mdewakanton band led a group that attacked the

Lower Sioux Agency

The Lower Sioux Agency, or Redwood Agency, was the federal administrative center for the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation in what became Redwood County, Minnesota, United States. It was the site of the Battle of Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 186 ...

(or Redwood Agency) and trading post located there. Later, settlers found Myrick among the dead with his mouth stuffed full of grass. Many of the upper Dakota (Sisseton and Wahpeton) wanted no part in the attacks

with the majority of the 4,000 members of the Sisseton and Wahpeton opposed to the war. Thus their bands did not participate in the early killings. Historian Mary Wingerd has stated that it is "a complete myth that all the Dakota people went to war against the United States" and that it was rather "a faction that went on the offensive".

Most of Little Crow's men surrendered shortly after the

Battle of Wood Lake

The Battle of Wood Lake occurred on September 23, 1862, and was the final battle in the Dakota War of 1862. The two-hour battle, which actually took place at nearby Lone Tree Lake, was a decisive victory for the U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry H ...

at

Camp Release

The Surrender at Camp Release was the final act in the Dakota War of 1862. After the Battle of Wood Lake, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley had considered pursuing the retreating Sioux, but he realized he did not have the resources for a vigorous pu ...

on September 26, 1862. Little Crow was forced to retreat sometime in September 1862. He stayed briefly in

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

but soon returned to the western Minnesota. He was killed on July 3, 1863, near

Hutchinson, Minnesota

Hutchinson is the largest city in McLeod County, Minnesota, United States. It lies along the South Fork of the Crow River. The population was 14,599 at the 2020 census.

History

The Hutchinson Family Singers (John, Asa, and Judson Hutchinson) ...

while gathering

raspberries

The raspberry is the edible fruit of a multitude of plant species in the genus ''Rubus'' of the rose family, most of which are in the subgenus '' Idaeobatus''. The name also applies to these plants themselves. Raspberries are perennial with ...

with his teenage son. The pair had wandered onto the land of a settler Nathan Lamson, who shot at them to collect bounties. Once it was discovered that the body was of Little Crow, his

skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

and scalp were put on display by the

Minnesota Historical Society

The Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) is a nonprofit educational and cultural institution dedicated to preserving the history of the U.S. state of Minnesota. It was founded by the territorial legislature in 1849, almost a decade before state ...

in St. Paul, Minnesota. The State held the trophies until 1971 when it returned the remains to Little Crow's grandson. For killing Little Crow the state increased the bounty to $500 when it paid Lamson.

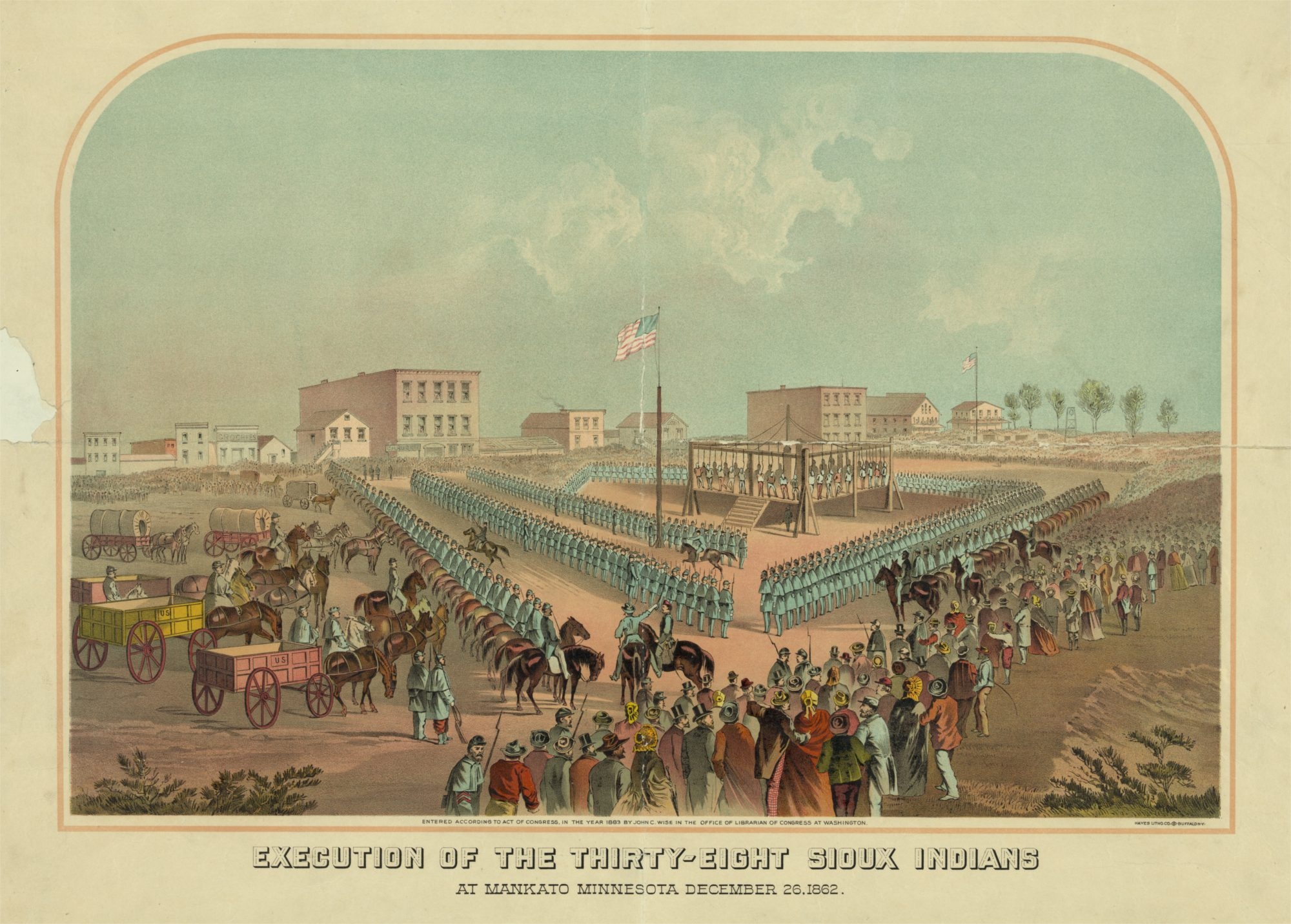

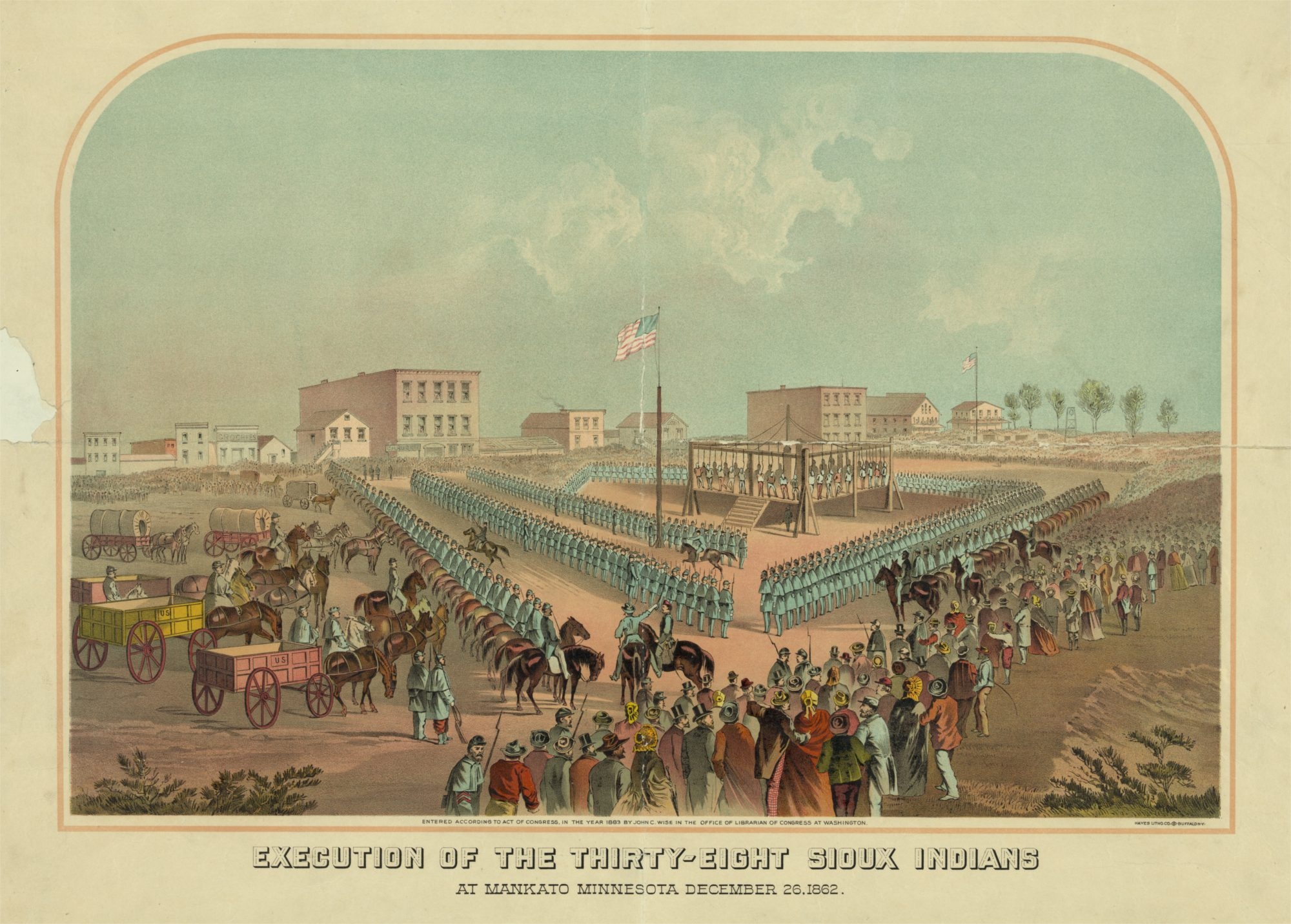

On November 5, 1862 a

military tribunal

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bod ...

found 303 mostly Mdewakanton tribesmen guilty of

rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

,

murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the ...

and

atrocities of hundreds of Minnesota settlers. They were sentenced to be hanged. The men had no attorneys or defense witnesses, and many were convicted in less than five minutes.

President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

commuted the death sentences of 284 of the warriors, while signing off on the hanging of 38 Santee men on December 26, 1862 in

Mankato, Minnesota

Mankato ( ) is a city in Blue Earth, Nicollet, and Le Sueur counties in the state of Minnesota. The population was 44,488 according to the 2020 census, making it the 21st-largest city in Minnesota, and the 5th-largest outside of the Minne ...

. It was the largest mass-execution in U.S. history, on US soil. The men remanded by order of President Lincoln were sent to a prison in

Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

, where more than half died.

Afterwards, the

US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

annulled all treaty agreements with the eastern Dakota and expelled the eastern Dakota with the Forfeiture Act of February 16, 1863, meaning all lands held by the eastern Dakota, and all annuities due to them, were forfeited to the US government.

During and after the hostilities, the majority of eastern Dakota fled Minnesota for the

Dakota territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

or

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Some settled in the

James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to

Crow Creek Reservation

The Crow Creek Indian Reservation ( dak, Khąǧí wakpá okášpe, '' lkt, Kȟaŋğí Wakpá Oyáŋke''), home to Crow Creek Sioux Tribe ( dak, Khąǧí wakpá oyáte) is located in parts of Buffalo, Hughes, and Hyde counties on the east ban ...

on the east bank of the

Missouri river.

There were as few as 50 eastern Dakota left in Minnesota by 1867.

Many had fled to the

Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska (created 1863), the

Flandreau Reservation (created 1869 from members who left the Santee Reservation), the

Lake Traverse and

Spirit Lake Reservations (both created 1867).

Those who fled to Canada throughout the 1870s now have descendants residing on nine small Dakota Reserves, five of which are located in

Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

(

Sioux Valley,

Dakota Plain,

Dakota Tipi,

Birdtail Creek, and

Canupawakpa Dakota) and the remaining four (

Standing Buffalo,

White Cap, Round Plain

ahpeton and Wood Mountain) in

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

. A few Dakota joined the Yanktonai and moved further west to join with the Lakota bands to continue their struggle against the United States military, later settling on the

Fort Peck Reservation in Montana.

Westward expansion of the Lakota

Prior to the 1650s, the Thítȟuŋwaŋ division of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ known as the Lakota was noted as being located east of the Red River,

and living on the fringes of the prairies and woods of the prairies of southern Minnesota and the eastern Dakotas by at least 1680.

According to Baptiste Good's

winter count

Winter counts (Lakota: ''waníyetu wówapi'' or ''waníyetu iyáwapi'') are pictorial calendars or histories in which tribal records and events were recorded by Native Americans in North America. The Blackfeet, Mandan, Kiowa, Lakota, and other Pla ...

, the Lakota had horses by 1700.

While the Dakota continued a subsistence cycle of corn, wild rice and hunting woodland animals, the Lakota increasing became reliant on bison for meat and its by-products (housing, clothing, tools) as they expanded their territory westward with the arrival of the horse.

After their adoption of

horse culture

A horse culture is a tribal group or community whose day-to-day life revolves around the herding and breeding of horses. Beginning with the domestication of the horse on the steppes of Eurasia, the horse transformed each society that adopted it ...

, Lakota society centered on the

buffalo hunt on horseback.

By the 19th century, the typical year of the Lakota was a

communal buffalo hunt as early in spring as their horses had recovered from the rigors of the winter. In June and July, the scattered bands of the tribes gathered together into large encampments, which included ceremonies such as the

Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individua ...

. These gatherings afforded leaders to meet to make political decisions, plan movements, arbitrate disputes, and organize and launch raiding expeditions or war parties. In the fall, people would split up into smaller bands to facilitate hunting to procure meat for the long winter. Between the fall hunt and the onset of winter was a time when Lakota warriors could undertake raiding and warfare. With the coming of winter snows, the Lakota settled into winter camps, where activities of the season, ceremonies and dances as well as trying to ensure adequate winter feed for their horses.

They began to dominate the prairies east of the Missouri river by the 1720s. At the same time, the Lakota branch split into two major sects, the Saône who moved to the

Lake Traverse area on the South Dakota–North Dakota–Minnesota border, and the Oglála-Sičháŋǧu who occupied the

James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

valley. However, by about 1750 the Saône had moved to the east bank of the

Missouri River, followed 10 years later by the Oglála and Brulé (Sičháŋǧu). By 1750, they had crossed the Missouri River and encountered Lewis and Clark in 1804. Initial United States contact with the Lakota during the

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

of 1804–1806 was marked by a standoff. Lakota bands refused to allow the explorers to continue upstream, and the expedition prepared for battle, which never came. In 1776, the Lakota defeated the Cheyenne for the

Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

, who had earlier taken the region from the

Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

.

The Cheyenne then moved west to the

Powder River country

The Powder River Country is the Powder River Basin area of the Great Plains in northeastern Wyoming, United States. The area is loosely defined as that between the Bighorn Mountains and the Black Hills, in the upper drainage areas of the Powd ...

,

and the Lakota made the Black Hills their home.

As their territory expanded, so did the number of rival groups they encountered. They secured an alliance with the Northern

Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

and Northern

Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

by the 1820s as intertribal warfare on the plains increased amongst the tribes for access to the dwindling population of buffalo.

The alliance fought the

Mandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still re ...

,

Hidatsa

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a paren ...

and

Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) for control of the

Missouri River in North Dakota.

By the 1840s, their territory expanded to the Powder River country in Montana, in which they fought with the Crow. Their victories over these tribes during this time period were aided by the fact those tribes were decimated by European diseases. Most of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara were killed by smallpox and almost half the population of the Crow were killed due to smallpox, cholera and other diseases.

In 1843, the southern Lakotas attacked Pawnee Chief Blue Coat's village near the

Loup in Nebraska, killing many and burning half of the earth lodges, and 30 years later, the Lakota again inflicted a blow so severe on the Pawnee during the

Massacre Canyon battle near Republican River. By the 1850s, the Lakota would be known as the most powerful tribe on the Plains.

Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851

The

Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was signed on September 17, 1851 between United States treaty commissioners and representatives of the Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations. Also known as Horse Cree ...

was signed on September 17, 1851, between

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

treaty commissioners and representatives of the

Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

, Sioux,

Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

,

Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

,

Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

,

Mandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still re ...

,

Hidatsa

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a paren ...

, and

Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) Nations. The treaty was an agreement between nine more or less independent parties. The treaty set forth traditional territorial claims of the tribes as among themselves. The United States acknowledged that all the land covered by the treaty was Indian territory and did not claim any part of it. The boundaries agreed to in the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851 would be used to settle a number of claims cases in the 20th century. The tribes guaranteed safe passage for

settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

s on the

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kans ...

and allowed roads and forts to be built in their territories in return for promises of an annuity in the amount of fifty thousand dollars for fifty years. The treaty should also "make an effective and lasting peace" among the eight tribes, each of them often at odds with a number of the others.

[Kappler, Charles J.: Indian Affairs. Laws and Treaties. Washington, 1904. Vol. 2, p. 594. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/sio0594.htm ]

The treaty was broken almost immediately after its inception by the Lakota and Cheyenne attacking the Crow over the next two years.

In 1858, the failure of the United States to prevent the mass immigration of miners and settlers into Colorado during the

Pike's Peak Gold Rush

The Pike's Peak Gold Rush (later known as the Colorado Gold Rush) was the boom in gold prospecting and mining in the Pike's Peak Country of western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory of the United States that began in July 1858 ...

, also did not help matters. They took over Indian lands in order to mine them, "against the protests of the Indians,"

and founded towns, started farms, and improved roads. Such immigrants competed with the tribes for game and water, straining limited resources and resulting in conflicts with the emigrants. The U.S. government did not enforce the treaty to keep out the immigrants.

[Paragraph 3]

Report to the President by the Indian Peace Commission, January 7, 1878

The situation escalated with the

Grattan affair in 1854 when a detachment of U.S. soldiers illegally entered a Sioux encampment to arrest those accused of stealing a cow, and in the process sparked a battle in which Chief Conquering Bear was killed.

Though intertribal fighting had existed before the arrival of white settlers, some of the post-treaty intertribal fighting can be attributed to mass killings of bison by white settlers and government agents. The U.S. Army did not enforce treaty regulations and allowed hunters onto Native land to slaughter buffalo, providing protection and sometimes ammunition. One hundred thousand buffalo were killed each year until they were on the verge of extinction, which threatened the tribes' subsistence. These mass killings affected all tribes thus the tribes were forced onto each other's hunting grounds, where fighting broke out.

On July 20, 1867, an

act of Congress

An Act of Congress is a statute enacted by the United States Congress. Acts may apply only to individual entities (called private laws), or to the general public ( public laws). For a bill to become an act, the text must pass through both house ...

created the

Indian Peace Commission "to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes".

The Indian Peace Commission was generally seen as a failure, and violence had reignited even before it was disbanded in October 1868. Two official reports were submitted to the federal government, ultimately recommending that the U.S. cease recognizing tribes as sovereign nations, refrain from making treaties with them, employ military force against those who refused to relocate to reservations, and move the

Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

from the

Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the ma ...

to the

Department of War War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

{{u ...

. The system of treaties eventually deteriorated to the point of collapse, and a decade of war followed the commission's work. It was the last major commission of its kind.

From 1866–1868, the Lakota fought the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

in the

Wyoming Territory

The Territory of Wyoming was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 25, 1868, until July 10, 1890, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne was the territorial capital. The bou ...

and the

Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

...

in what is known as

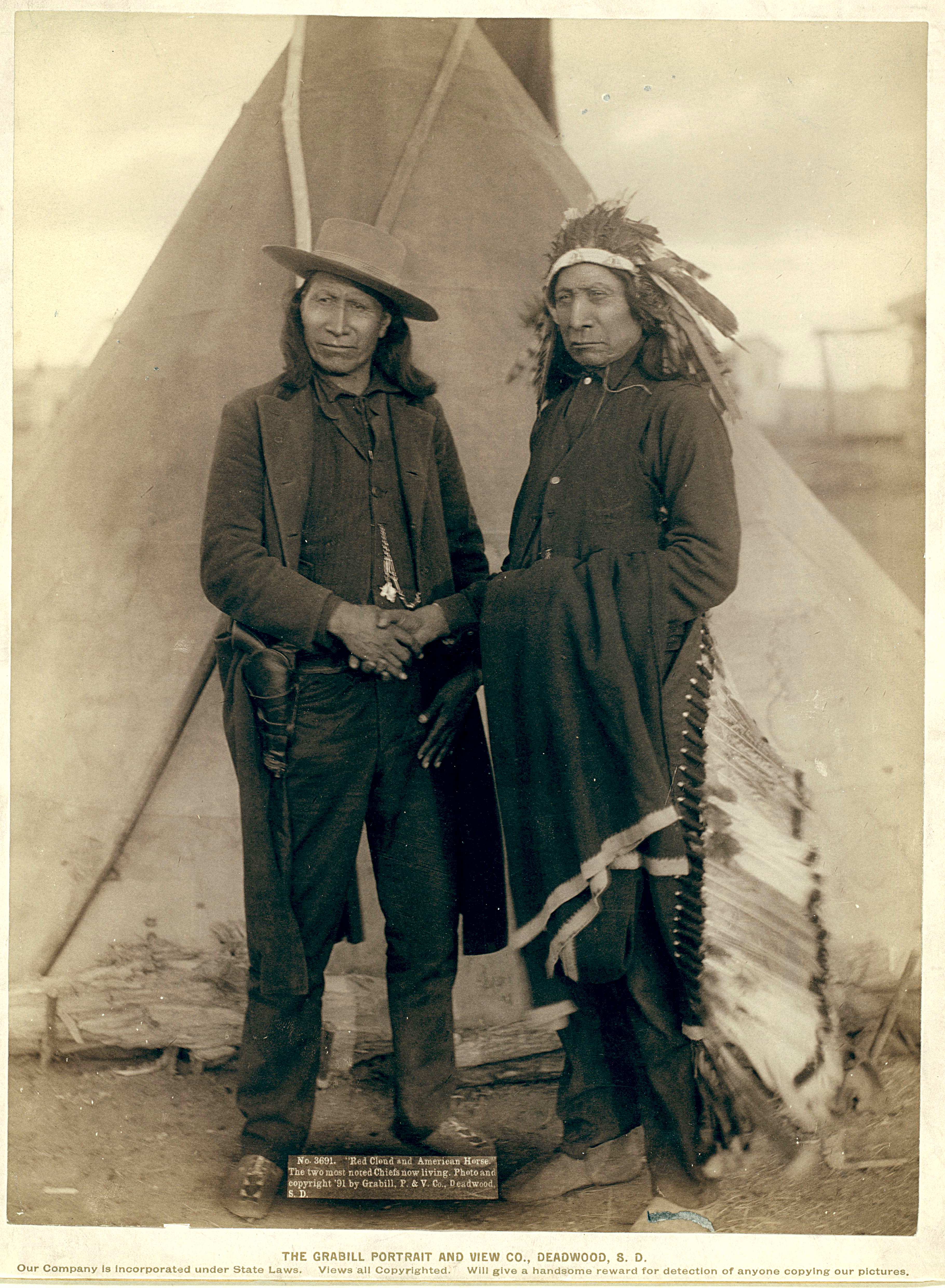

Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War or the Powder River War) was an armed conflict between an alliance of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho peoples against the United States that took place in the Wyoming and M ...

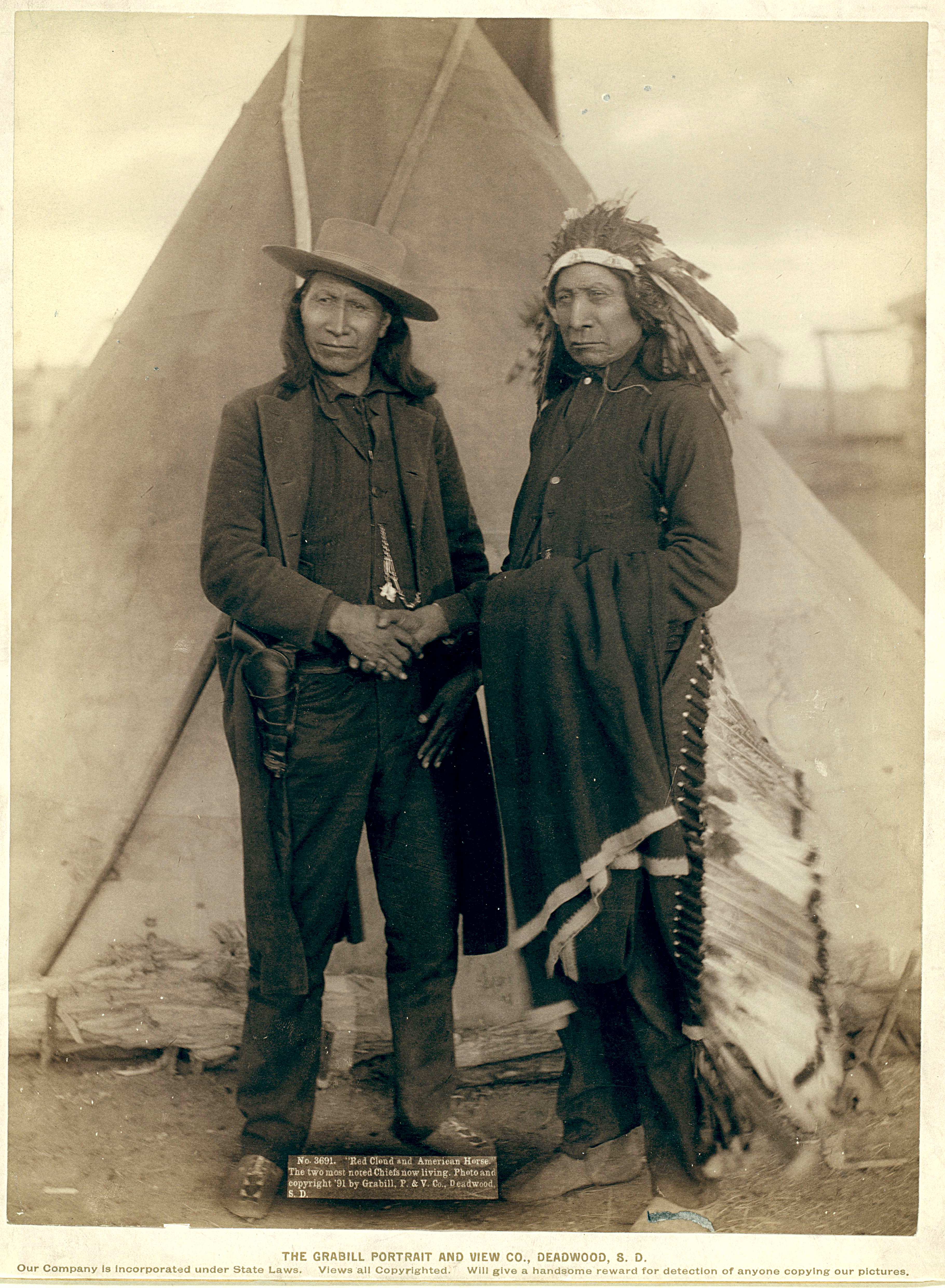

(also referred to as the Bozeman War). The war is named after

Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...