Norman Foster Ramsey Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norman Foster Ramsey Jr. (August 27, 1915 – November 4, 2011) was an American

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two Allied aircraft large enough: the British Avro Lancaster and the US Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) wanted to use the B-29 if at all possible, even though it required substantial modification. Ramsey supervised the test drop program, which began at

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two Allied aircraft large enough: the British Avro Lancaster and the US Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) wanted to use the B-29 if at all possible, even though it required substantial modification. Ramsey supervised the test drop program, which began at

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student

"Proton–Proton Scattering at 105 MeV and 75 MeV"

"Inelastic Scattering Of Electrons By Protons"

Department of Physics at

"Determination of the Neutron Magnetic Moment"

Group photograph

taken at ''Lasers'' '93 including (right to left) Norman F. Ramsey,

Norman Ramsey, an oral history conducted in 1995 by Andrew Goldstein, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Papers relating to the Manhattan Project, 1945–1946, collected by Norman Ramsey

Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Libraries, from SIRIS * including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1989 ''Experiments with Separated Oscillatory Fields and Hydrogen Masers'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Ramsey, Norman Foster 1915 births 2011 deaths Columbia College (New York) alumni Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Columbia University faculty Harvard University faculty Nobel laureates in Physics National Medal of Science laureates American Nobel laureates IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Vannevar Bush Award recipients Manhattan Project people Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences American physicists People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki University of Michigan staff Fellows of the American Physical Society Presidents of the American Physical Society Members of the American Philosophical Society

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who was awarded the 1989 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

, for the invention of the separated oscillatory field method, which had important applications in the construction of atomic clock

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions betwe ...

s. A physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

professor at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

for most of his career, Ramsey also held several posts with such government and international agencies as NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

and the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

. Among his other accomplishments are helping to found the United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

's Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory located in Upton, Long Island, and was formally established in 1947 at the site of Camp Upton, a former U.S. Army base and Japanese internment c ...

and Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been opera ...

.

Early life

Norman Foster Ramsey Jr. was born inWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, on August 27, 1915, to Minna Bauer Ramsey, an instructor at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. T ...

, and Norman Foster Ramsey, a 1905 graduate of the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and an officer in the Ordnance Department

The United States Army Ordnance Corps, formerly the United States Army Ordnance Department, is a sustainment branch of the United States Army, headquartered at Fort Lee, Virginia. The broad mission of the Ordnance Corps is to supply Army comb ...

who rose to the rank of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, commanding the Rock Island Arsenal

The Rock Island Arsenal comprises , located on Arsenal Island, originally known as Rock Island, on the Mississippi River between the cities of Davenport, Iowa, and Rock Island, Illinois. It lies within the state of Illinois. Rock Island ...

. He was raised as an Army brat

A military brat (colloquial or military slang) is a child of serving or retired military personnel. Military brats are associated with a unique subcultureDavid C. Pollock, Ruth E. van Reken. ''Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds'', Revis ...

, frequently moving from post to post, and lived in France for a time when his father was Liaison Officer with the ''Direction d'Artillerie'' and Assistant Military Attaché. This allowed him to skip a couple of grades along the way, so that he graduated from Leavenworth High School

Leavenworth High School is a public high school located in Leavenworth, Kansas, operated by Leavenworth USD 453 school district. The school was established in 1865, making it one of the first high schools in Kansas. The school colors are blue and ...

in Leavenworth, Kansas, at the age of 15.

Ramsey's parents hoped that he would go to West Point, but at 15, he was too young to be admitted. He was awarded a scholarship to the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. T ...

, but in 1930 his father was posted to Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk Channel. The National Park ...

, New York. Ramsey therefore entered Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in 1931, and began studying engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

. He became interested in mathematics, and switched to this as his academic major

An academic major is the academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits. A student who successfully completes all courses required for the major qualifies for an undergraduate degree. The word ''major'' (also called ''conc ...

. By the time he received his BA from Columbia in 1935, he had become interested in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

. Columbia awarded him a Kellett Fellowship to Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III of England, Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world' ...

where he studied physics at Cavendish Laboratory under Lord Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

and Maurice Goldhaber

Maurice Goldhaber (April 18, 1911 – May 11, 2011) was an American physicist, who in 1957 (with Lee Grodzins and Andrew Sunyar) established that neutrinos have negative helicity.

Early life and childhood

He was born on April 18, 1911, in ...

, and encountered notable physicists including Edward Appleton, Max Born, Edward Bullard

Sir Edward Crisp Bullard FRS (21 September 1907 – 3 April 1980) was a British geophysicist who is considered, along with Maurice Ewing, to have founded the discipline of marine geophysics. He developed the theory of the geodynamo, pioneere ...

, James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

, John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

, Paul Dirac

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English theoretical physicist who is regarded as one of the most significant physicists of the 20th century. He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the Univer ...

, Arthur Eddington, Ralph Fowler, Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

and J.J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be discovered.

In 1897, Thomson showed that ...

. At Cambridge, he took the tripos

At the University of Cambridge, a Tripos (, plural 'Triposes') is any of the examinations that qualify an undergraduate for a bachelor's degree or the courses taken by a student to prepare for these. For example, an undergraduate studying mathe ...

in order to study quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistr ...

, which had not been covered at Columbia, resulting in being awarded a second BA degree by Cambridge.

A term paper Ramsey wrote for Goldhaber on magnetic moment

In electromagnetism, the magnetic moment is the magnetic strength and orientation of a magnet or other object that produces a magnetic field. Examples of objects that have magnetic moments include loops of electric current (such as electromagne ...

s caused him to read recent papers on the subject by Isidor Isaac Rabi

Isidor Isaac Rabi (; born Israel Isaac Rabi, July 29, 1898 – January 11, 1988) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance, which is used in magnetic resonance ima ...

, and this stimulated an interest in molecular beams, and in doing research for a PhD under Rabi at Columbia. Soon after Ramsey arrived at Columbia, Rabi invented molecular beam resonance spectroscopy, for which he was awarded the Nobel prize in physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1944. Ramsey was part of Rabi's team that also included Jerome Kellogg, Polykarp Kusch

Polykarp Kusch (January 26, 1911 – March 20, 1993) was a German-born American physicist. In 1955, the Nobel Committee gave a divided Nobel Prize for Physics, with one half going to Kusch for his accurate determination that the magnetic momen ...

, Sidney Millman

Sidney may refer to:

People

* Sidney (surname), English surname

* Sidney (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Sidney (footballer, born 1972), full name Sidney da Silva Souza, Brazilian football defensive midfielder

* ...

and Jerrold Zacharias. Ramsey worked with them on the first experiments making use of the new technique, and shared with Rabi and Zacharias in the discovery that the deuteron

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being protium, or hydrogen-1). The nucleus of a deuterium atom, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one n ...

was a magnetic quadrupole

A quadrupole or quadrapole is one of a sequence of configurations of things like electric charge or current, or gravitational mass that can exist in ideal form, but it is usually just part of a multipole expansion of a more complex structure refl ...

. This meant that the atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron ...

was not spherical, as had been thought. He received his PhD in physics from Columbia in 1940, and became a fellow at the Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. T ...

in Washington, D.C., where he studied neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

- proton and proton-helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

scattering.

World War II

Radiation laboratory

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of

In 1940, he married Elinor Jameson of Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, and accepted a teaching position at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the Univer ...

. The two expected to spend the rest of their lives there, but World War II intervened. In September 1940 the British Tizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a British delegation that visited the United States during WWII to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development ( ...

brought a number of new technologies to the United States, including a cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field whi ...

, a high-powered device that generates microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

s using the interaction of a stream of electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

s with a magnetic field, which promised to revolutionize radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

. Alfred Lee Loomis

Alfred Lee Loomis (November 4, 1887 – August 11, 1975) was an American attorney, investment banker, philanthropist, scientist, physicist, inventor of the LORAN Long Range Navigation System and a lifelong patron of scientific research. He estab ...

of the National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

established the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

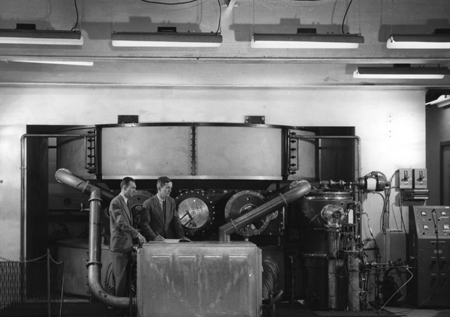

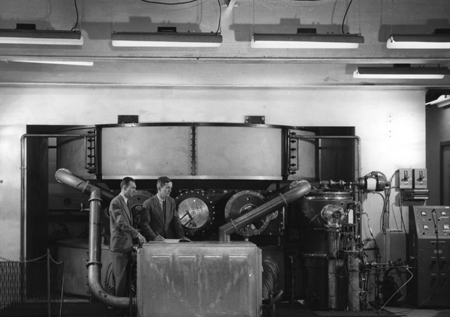

to develop this technology. Ramsey was one of the scientists recruited by Rabi for this work.

Initially, Ramsey was in Rabi's magnetron group. When Rabi became a division head, Ramsey became the group leader. The role of the group was to develop the magnetron to permit a reduction in wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, t ...

from to , and then to or X-Band. Microwave radar promised to be small, lighter and more efficient than older types. Ramsey's group started with the design produced by Oliphant's team in Britain, and attempted to improve it. The Radiation Laboratory produced the designs, which were prototyped by Raytheon

Raytheon Technologies Corporation is an American multinational aerospace and defense conglomerate headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. It is one of the largest aerospace and defense manufacturers in the world by revenue and market capitali ...

, and then tested by the laboratory. In June 1941, Ramsey travelled to Britain, where he met with Oliphant, and the two exchanged ideas. He brought back some British components which were incorporated into the final design. A night fighter

A night fighter (also known as all-weather fighter or all-weather interceptor for a period of time after the Second World War) is a fighter aircraft adapted for use at night or in other times of bad visibility. Night fighters began to be used i ...

aircraft, the Northrop P-61 Black Widow

The Northrop P-61 Black Widow is a twin-engine United States Army Air Forces fighter aircraft of World War II. It was the first operational U.S. warplane designed as a night fighter, and the first aircraft designed specifically as a night figh ...

, was designed around the new radar. Ramsey returned to Washington in late 1942 as an adviser on the use of the new 3 cm microwave radar sets that were now coming into service, working for Edward L. Bowles in the office of the Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

.

Manhattan Project

In 1943, Ramsey was approached byRobert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

and Robert Bacher, who asked him to join the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Ramsey agreed to do so, but the intervention of the Project director, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves Jr.

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers Officer (armed forces), officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and di ...

, was necessary in order to prise him away from the Secretary of War's office. A compromise was agreed to, whereby Ramsey remained on the payroll of the Secretary of War, and was merely seconded to the Manhattan Project. In October 1943, Group E-7 of the Ordnance Division was created at the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

with Ramsey as group leader, with the task of integrating the design and delivery of the nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s being built by the laboratory.

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two Allied aircraft large enough: the British Avro Lancaster and the US Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) wanted to use the B-29 if at all possible, even though it required substantial modification. Ramsey supervised the test drop program, which began at

The first thing he had to do was determine the characteristics of the aircraft that would be used. There were only two Allied aircraft large enough: the British Avro Lancaster and the US Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) wanted to use the B-29 if at all possible, even though it required substantial modification. Ramsey supervised the test drop program, which began at Dahlgren, Virginia

Dahlgren is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in King George County, Virginia, United States. The population was 2,946 at the time of the 2020 census, up from 2,653 at the 2010 census, and up from 997 in 2000.

History ...

, in August 1943, before moving to Muroc Dry Lake, California, in March 1944. Mock ups of Thin Man and Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

bombs were dropped and tracked by an SCR-584

The SCR-584 (short for '' Set, Complete, Radio # 584'') was an automatic-tracking microwave radar developed by the MIT Radiation Laboratory during World War II. It was one of the most advanced ground-based radars of its era, and became one of the ...

ground-based radar set of the kind that Ramsey had helped develop at the Radiation laboratory. Numerous problems were discovered with the bombs and the aircraft modifications, and corrected.

Plans for the delivery of the weapons in combat were assigned to the Weapons Committee, which was chaired by Ramsey, and answerable to Captain William S. Parsons. Ramsey drew up tables of organization and equipment for the Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 1 ...

detachment that would accompany the USAAF's 509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was a unit of the United States Army Air Forces created during World War II and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons. It conducted the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in ...

to Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the ...

. Ramsey briefed the 509th's commander, Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, on the nature of the mission when the latter assumed command of the 509th. Ramsey went to Tinian with the Project Alberta detachment as Parsons's scientific and technical deputy. He was involved in the assembly of the Fat Man bomb, and relayed Parsons's message indicating the success of the bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

to Groves in Washington, D.C.

Research

At the end of the war, Ramsey returned to Columbia as a professor and research scientist. Rabi and Ramsey picked up where they had left off before the war with their molecular beam experiments. Ramsey and his first graduate student, William Nierenberg, measured various nuclearmagnetic dipole

In electromagnetism, a magnetic dipole is the limit of either a closed loop of electric current or a pair of poles as the size of the source is reduced to zero while keeping the magnetic moment constant. It is a magnetic analogue of the electric ...

and electric quadrupole moments. With Rabi, he helped establish the Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory located in Upton, Long Island, and was formally established in 1947 at the site of Camp Upton, a former U.S. Army base and Japanese internment c ...

on Long Island. In 1946, he became the first head of the Physics Department there. His time there was brief, for in 1947, he joined the physics faculty at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, where he would remain for the next 40 years, except for brief visiting professorships at Middlebury College, Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

, Mt. Holyoke College and the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

. During the 1950s, he was the first science adviser to NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, and initiated a series of fellowships, grants and summer school programs to train European scientists.

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student

Ramsey's research in the immediate post-war years looked at measuring fundamental properties of atoms and molecules by use of molecular beams. On moving to Harvard, his objective was to carry out accurate molecular beam magnetic resonance experiments, based on the techniques developed by Rabi. However, the accuracy of the measurements depended on the uniformity of the magnetic field, and Ramsey found that it was difficult to create sufficiently uniform magnetic fields. He developed the separated oscillatory field method in 1949 as a means of achieving the accuracy he wanted.

Ramsey and his PhD student Daniel Kleppner

Daniel Kleppner, born 1932, is the Lester Wolfe Professor Emeritus of Physics at MIT and co-director of the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms. His areas of science include Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics, and his research interest ...

developed the atomic hydrogen maser

A maser (, an acronym for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) is a device that produces coherent electromagnetic waves through amplification by stimulated emission. The first maser was built by Charles H. Townes, Ja ...

, looking to increase the accuracy with which the hyperfine

In atomic physics, hyperfine structure is defined by small shifts in otherwise degenerate energy levels and the resulting splittings in those energy levels of atoms, molecules, and ions, due to electromagnetic multipole interaction between the nuc ...

separations of atomic hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

, deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being protium, or hydrogen-1). The nucleus of a deuterium atom, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one ...

and tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of ...

could be measured, as well as to investigate how much the hyperfine structure was affected by external magnetic and electric fields. He also participated in developing an extremely stable clock based on a hydrogen maser. From 1967 until 2019, the second has been defined based on 9,192,631,770 hyperfine transition of a cesium-133

Caesium (55Cs) has 40 known isotopes, making it, along with barium and mercury (element), mercury, one of the elements with the most isotopes. The atomic masses of these isotopes range from 112 to 151. Only one isotope, 133Cs, is stable. The longe ...

atom; the atomic clock

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions betwe ...

which is used to set this standard is an application of Ramsey's work. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1989 "for the invention of the separated oscillatory fields method and its use in the hydrogen maser and other atomic clocks". The Prize was shared with Hans G. Dehmelt

Hans Georg Dehmelt (; 9 September 1922 – 7 March 2017) was a German and American physicist, who was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989, for co-developing the ion trap technique (Penning trap) with Wolfgang Paul, for which they shared one- ...

and Wolfgang Paul.

In collaboration with the Institut Laue–Langevin

The Institut Laue–Langevin (ILL) is an internationally financed scientific facility, situated on the Polygone Scientifique in Grenoble, France. It is one of the world centres for research using neutrons. Founded in 1967 and honouring the ph ...

, Ramsey also worked on applying similar methods to beams of neutrons, measuring the neutron magnetic moment

The nucleon magnetic moments are the intrinsic magnetic dipole moments of the proton and neutron, symbols ''μ''p and ''μ''n. Protons and neutrons, both nucleons, comprise the nucleus of atoms, and both nucleons behave as small magnets whose ...

and finding a limit to its electric dipole moment. As President of the Universities Research Association during the 1960s he was involved in the design and construction of the Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been opera ...

in Batavia, Illinois

Batavia () is a city mainly in Kane County and partly in DuPage County in the U.S. state of Illinois. Located in the Chicago metropolitan area, it was founded in 1833 and is the oldest city in Kane County. Per the 2020 census, the population w ...

. He also headed a 1982 National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

committee that concluded that, contrary to the findings of the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations, acoustic evidence did not indicate the presence of a second gunman's involvement in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Later life

Ramsey eventually became theEugene Higgins professor of physics

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

at Harvard and retired in 1986. However, he remained active in physics, spending a year as a research fellow at the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics

JILA, formerly known as the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics, is a physical science research institute in the United States. JILA is located on the University of Colorado Boulder campus. JILA was founded in 1962 as a joint institute of ...

(JILA) at the University of Colorado

The University of Colorado (CU) is a system of public universities in Colorado. It consists of four institutions: University of Colorado Boulder, University of Colorado Colorado Springs, University of Colorado Denver, and the University o ...

. He also continued visiting professorships at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, Williams College

Williams College is a private liberal arts college in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It was established as a men's college in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim Williams, a colonist from the Province of Massachusetts Bay who was kill ...

and the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

. In addition to the Nobel Prize in Physics, Ramsey received a number of awards, including the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award

The Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award was established in 1959 in honor of a scientist who helped elevate American physics to the status of world leader in the field.

E. O. Lawrence was the inventor of the cyclotron, an accelerator of subatomic par ...

in 1960, Davisson-Germer Prize in 1974, the IEEE Medal of Honor

The IEEE Medal of Honor is the highest recognition of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). It has been awarded since 1917, when its first recipient was Major Edwin H. Armstrong. It is given for an exceptional contributio ...

in 1984, the Rabi Prize in 1985, the Rumford Premium Prize in 1985, the Compton Medal in 1986, and the Oersted Medal

The Oersted Medal recognizes notable contributions to the teaching of physics. Established in 1936, it is awarded by the American Association of Physics Teachers. The award is named for Hans Christian Ørsted. It is the Association's most prest ...

and the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

in 1988. In 1990, Ramsey received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

. He was an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

, the United States National Academy of Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

. In 2004, he signed a letter along with 47 other Nobel laureates endorsing John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party, he ...

for President of the United States as someone who would "restore science to its appropriate place in government".

His first wife, Elinor, died in 1983, after which he married Ellie Welch of Brookline, Massachusetts. Ramsey died on November 4, 2011. He was survived by his wife Ellie, his four daughters from his first marriage, and his stepdaughter and stepson from his second marriage.

Bibliography

*Ramsey, N. F.; Birge, R. W. & U. E. Kruse"Proton–Proton Scattering at 105 MeV and 75 MeV"

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

(through predecessor agency the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

), (January 31, 1951).

*Ramsey, N. F.; Cone, A. A.; Chen, K. W.; Dunning, J. R. Jr.; Hartwig, G.; Walker, J. K. & R. Wilson"Inelastic Scattering Of Electrons By Protons"

Department of Physics at

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

(through predecessor agency the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

), (December 1966).

*Greene, G. L.; Ramsey, N. F.; Mampe, W.; Pendlebury, J. M.; Smith, K. ; Dress, W. B.; Miller, P. D. & P. Perrin"Determination of the Neutron Magnetic Moment"

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a U.S. multiprogram science and technology national laboratory sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and administered, managed, and operated by UT–Battelle as a federally funded research an ...

, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, Institut Laue–Langevin

The Institut Laue–Langevin (ILL) is an internationally financed scientific facility, situated on the Polygone Scientifique in Grenoble, France. It is one of the world centres for research using neutrons. Founded in 1967 and honouring the ph ...

, Astronomy Centre of Sussex University, United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

, (June 1981).

*Ramsey, N. F. ''Molecular Beams'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

(First edition 1956, Reprinted 1986).

Notes

References

* * * * * * *External links

Group photograph

taken at ''Lasers'' '93 including (right to left) Norman F. Ramsey,

Marlan Scully

Marlan Orvil Scully (born August 3, 1939) is an American physicist best known for his work in theoretical quantum optics. He is a professor at Texas A&M University and Princeton University. Additionally, in 2012 he developed a lab at the Baylor ...

, and F. J. Duarte.Norman Ramsey, an oral history conducted in 1995 by Andrew Goldstein, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Papers relating to the Manhattan Project, 1945–1946, collected by Norman Ramsey

Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Libraries, from SIRIS * including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1989 ''Experiments with Separated Oscillatory Fields and Hydrogen Masers'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Ramsey, Norman Foster 1915 births 2011 deaths Columbia College (New York) alumni Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Columbia University faculty Harvard University faculty Nobel laureates in Physics National Medal of Science laureates American Nobel laureates IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Vannevar Bush Award recipients Manhattan Project people Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences American physicists People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki University of Michigan staff Fellows of the American Physical Society Presidents of the American Physical Society Members of the American Philosophical Society