Nomination and confirmation to the Supreme Court of the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The nomination and confirmation of justices to the Supreme Court of the United States involves several steps, the framework for which is set forth in the United States Constitution. Specifically, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2, provides that the

Once a Supreme Court vacancy opens, the president discusses the candidates with advisors, Senate leaders and members of the

Once a Supreme Court vacancy opens, the president discusses the candidates with advisors, Senate leaders and members of the

The Appointments Clause does not set qualifications for being a Supreme Court justice (e.g. age,

The Appointments Clause does not set qualifications for being a Supreme Court justice (e.g. age,  Throughout much of the nation's history, presidents also nominated individuals based upon geographical considerations. President

Throughout much of the nation's history, presidents also nominated individuals based upon geographical considerations. President

Under Senate rules, nominations still pending when the Senate adjourns at the end of a session or recesses for more than 30 days are returned to the president unless the Senate, by

Under Senate rules, nominations still pending when the Senate adjourns at the end of a session or recesses for more than 30 days are returned to the president unless the Senate, by

Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution empowers the president to fill critical federal executive and judicial branch vacancies unilaterally but temporarily when the Senate is in recess, and thus unavailable to provide advice and consent. Such

Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution empowers the president to fill critical federal executive and judicial branch vacancies unilaterally but temporarily when the Senate is in recess, and thus unavailable to provide advice and consent. Such

The widening of the partisan divide over judicial nominations corresponds with the prolongation of the confirmation process. From the establishment of the Supreme Court up to the early 1950s, the process of approving justices was usually rapid. The average time between nomination and confirmation was 13.2 days. Eight justices during that era were confirmed on the same day they were formally nominated, including

The widening of the partisan divide over judicial nominations corresponds with the prolongation of the confirmation process. From the establishment of the Supreme Court up to the early 1950s, the process of approving justices was usually rapid. The average time between nomination and confirmation was 13.2 days. Eight justices during that era were confirmed on the same day they were formally nominated, including

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by

When a chief justice vacancy occurs, the president may choose to nominate an

When a chief justice vacancy occurs, the president may choose to nominate an

Supreme Court Nominations Research Guide

Georgetown University Law Library.

Supreme Court of the United States

website

United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

website {{Nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

nominates a justice and that the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

provides Advice and consent

Advice and consent is an English phrase frequently used in enacting formulae of bills and in other legal or constitutional contexts. It describes either of two situations: where a weak executive branch of a government enacts something prev ...

before the person is formally appointed to the Court. It also empowers a president to temporarily, under certain circumstances, fill a Supreme Court vacancy by means of a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

. The Constitution does not set any qualifications for service as a justice, thus the president may nominate any individual to serve on the Court.

In modern practice, Supreme Court nominations are first referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

before being considered by the full Senate. Since the late 1960s, the committee's examination of a Supreme Court nominee almost always has consisted of three parts: a pre-hearing investigation, followed by public hearings in which both the nominee and other witnesses make statements and answer questions, and concluding with a committee decision on what recommendation to make to the full Senate (favorable, unfavorable or no recommendation). Once that recommendation is reported to the Senate, floor debate can begin ahead of a confirmation vote. A simple majority vote is needed for confirmation.

The process for replacing a Supreme Court justice attracts considerable public attention and is closely scrutinized. Typically, the whole process takes several months, but it can be, and on occasion has been, completed more quickly. Since the mid 1950s, the average time from nomination to final Senate vote has been about 55 days. Presidents generally select a nominee a few weeks after a vacancy occurs or a retirement is announced. The number of hours each nominee has spent before the Senate Judiciary Committee for public testimony has varied; the six nominees who have appeared before the committee since 2005 spent between 17 and hours testifying.

Constitutional background

TheAppointments Clause

The Appointments Clause of Article II, Section 2, Clause 2, of the United States Constitution empowers the President of the United States to nominate and, with the advice and consent (confirmation) of the United States Senate, appoint public offi ...

in Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution empowers the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

to nominate and, with the confirmation (advice and consent

Advice and consent is an English phrase frequently used in enacting formulae of bills and in other legal or constitutional contexts. It describes either of two situations: where a weak executive branch of a government enacts something prev ...

) of the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, to appoint public officials, including justices of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

. This clause, commonly known as the Appointments Clause, is one example of the system of checks and balances inherent in the Constitution. The president has the plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

to nominate and to appoint, while the Senate possesses the plenary power to reject or confirm the nominee prior to their appointment.

Alexander Hamilton wrote about the way the Constitution allocates the power of appointment in The Federalist No. 76 (1778). The president, he asserted, should have the sole power to nominate because "one man of discernment is better fitted to analyze and estimate the peculiar qualities adapted to particular offices, than a body of men of equal, or perhaps even of superior discernment." And, requiring the cooperation of the Senate would, he contended, "have a powerful, though, in general, a silent operation. It would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to preventing the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity. In addition to this, it would be an efficacious source of stability in the administration."

Nomination

Nominee selection

White House staff members typically handle the vetting and recommending of potential Supreme Court nominees. In practice, the task of conducting background research on and preparing profiles of possible candidates for the Supreme Court is among the first taken on by an incoming president's staff, vacancy or not. As there was a Supreme Court vacancy at the time of the2016 presidential campaign

This national electoral calendar for 2016 lists the national/ federal elections held in 2016 in all sovereign states and their dependent territories. By-elections are excluded, though national referendums are included.

January

*7 January: Kiri ...

, advisors to then-candidate Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

developed, and Trump made public, two lists of potential Supreme Court nominees.

Once a Supreme Court vacancy opens, the president discusses the candidates with advisors, Senate leaders and members of the

Once a Supreme Court vacancy opens, the president discusses the candidates with advisors, Senate leaders and members of the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

, as a matter of senatorial courtesy

Senatorial courtesy is a long-standing, unwritten, unofficial, and nonbinding constitutional convention in the United States describing the tendency of U.S. senators to support a Senate colleague when opposing the appointment to federal office of ...

, before selecting a nominee,. In doing so, potential problems a nominee may face during confirmation can be addressed in advance. This can also be an opportunity for senators to advise the president, though president is not obliged to take their advice on whom to nominate, neither does the Senate have the authority to set qualifications or otherwise limit who the president may select.

As the president considers who to nominate, formal investigations into the backgrounds of prospective nominees are conducted. In recent decades this process has involved both an inquiry into the public record and professional credentials of persons under consideration, and an inquiry into the private background of potential candidates. The former is usually conducted senior White House aides in consultation with the Justice Department. The latter is conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

. The goal of these inquiries is to ensure that a nominee has nothing in their background that would prove embarrassing or would otherwise put confirmation in jeopardy.

As the president prepares to announce their selection, a former senator of the president's party is selected to serve as the nominee's sherpa Sherpa may refer to:

Ethnography

* Sherpa people, an ethnic group in north eastern Nepal

* Sherpa language

Organizations and companies

* Sherpa (association), a French network of jurists dedicated to promoting corporate social responsibility

* ...

, their guide through the process. When ready, the president publicly announces the selection, with the nominee present. Shortly thereafter, the nomination then is formally submitted to the Senate. Once that has been done, it is customary for a nominee to meet with senators while also preparing for confirmation hearings.

How quickly a president selects a nominee has varied from president to president and from instance to instance. For the 14 vacancies since 1975 that required only one nomination prior to being filled, the average length of time between the date it was publicly known that a justice was leaving the court (or had died) and the date on which the president publicly identified a nominee for the vacancy was about 19 days.

Criteria

The Appointments Clause does not set qualifications for being a Supreme Court justice (e.g. age,

The Appointments Clause does not set qualifications for being a Supreme Court justice (e.g. age, citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

or admission to the bar) nor does it describe the intellectual or temperamental qualities that justices should possess. As a result, each president has had their own criteria for selecting individuals to fill Supreme Court vacancies. While specific motives vary from president to president and situation to situation, the motivations behind the choices made can be grouped into two general categories: professional qualifications criteria and politicalpublic policy criteria.

Most presidents have intentionally sought out nominees with solid legal qualifications, persons with a distinguished reputation or expertise in a particular area of the law, or who is highly regarded for their public service. As a result, many nominees have had prior experience as lower court judges, legal scholars, or private practitioners, or have served as Members of Congress, as federal administrators, or as governors. Even though neither the Constitution nor federal law requires that a Supreme Court justice be a lawyer, every person nominated to the Court to date has been.

Most presidents have nominated individuals who broadly share their political views or ideological philosophy. During the 20th century for example, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

chose people whom he believed would affirm his New Deal programs. Similarly, John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

chose people whom they anticipated would support their respective New Frontier

The term ''New Frontier'' was used by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in his acceptance speech in the 1960 United States presidential election to the Democratic National Convention at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as the ...

and Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

initiatives. Ronald Reagan chose conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

jurists, people he believed would further his goal of undoing the activism of the Warren and Burger Court

The Burger Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1969 to 1986, when Warren Burger served as Chief Justice of the United States. Burger succeeded Earl Warren as Chief Justice after the latter's retir ...

s.

On occasion, a justice's decisions may be contrary to what the nominating president anticipated. One such justice was David Souter

David Hackett Souter ( ; born September 17, 1939) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1990 until his retirement in 2009. Appointed by President George H. W. Bush to fill the seat ...

, who was nominated by George H. W. Bush. When nominated, he was not well known and had no paper trail whatsoever. Many pundits and politicians at the time expected Souter to be a conservative; however, after becoming a justice, his opinions generally fell on the liberal side of the political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more geometric axes that represent independent political dimensions. The expressions politi ...

.

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

established this practice, intentionally combining geography with his other considerations when making judicial and other appointments. Of his first six Supreme court appointments in 1789, two were from the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

, two from the Mid-Atlantic and two from the South. From 1789 until 1971, with the exception of the 1865–76 Reconstruction Era, there was always a southerner on the Court; similarly, from 1789 through 1932 there was always a New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

er as well. Since the mid-1970s, however, the role of geography in the selection process has been minimal.

Beginning in the mid 20th Century, concerns about diversity on the Court with regard to religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

, race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

, and gender

Gender is the range of characteristics pertaining to femininity and masculinity and differentiating between them. Depending on the context, this may include sex-based social structures (i.e. gender roles) and gender identity. Most cultures ...

have also been of particular importance to various presidents. In 1956, Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

appointed William J. Brennan Jr., a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, to the Court. Eisenhower sought a Catholic to appoint—in part because there had been no Catholic justice since 1949, and in part because Eisenhower was directly lobbied by Cardinal Francis Spellman of the Archdiocese of New York

The Archdiocese of New York ( la, Archidiœcesis Neo-Eboracensis) is an ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church ( particularly the Roman Catholic or Latin Church) located in the State of New York. It encompasses the boroug ...

to make such an appointment. Lyndon B. Johnson, as part of his strategy to implement the his civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

agenda, appointed the first African-American justice, Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

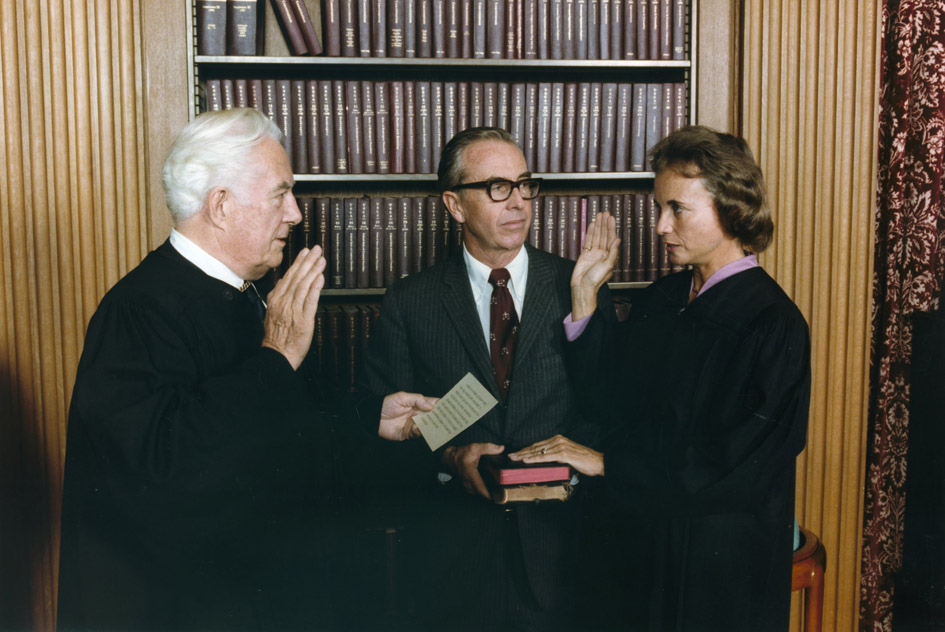

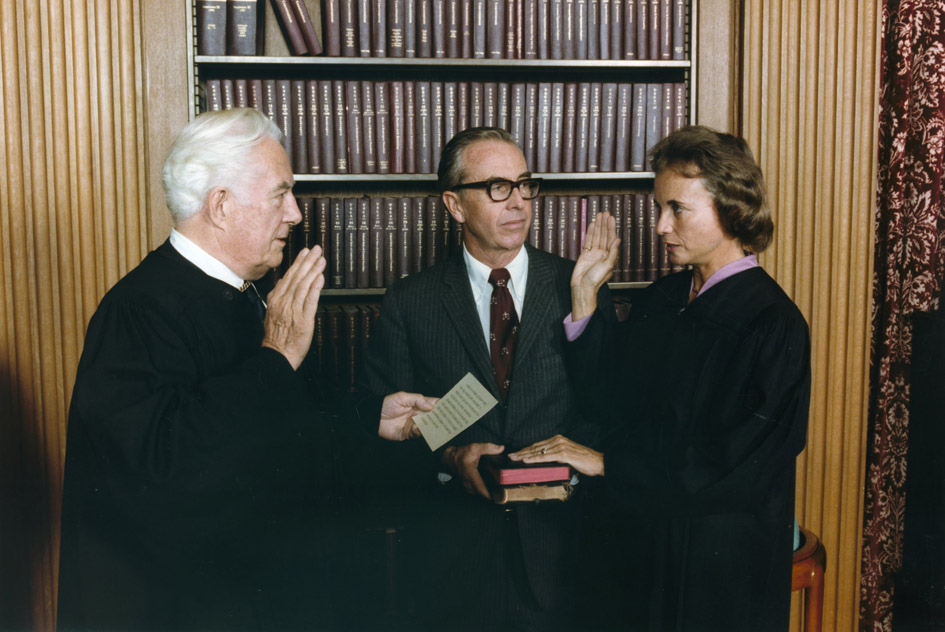

, in 1967. Ronald Reagan pledged during his 1980 presidential campaign to nominate the first woman to the Supreme Court. In 1981, he nominated Sandra Day O'Connor.

An additional consideration is age; the younger the person, the longer they could conceivably serve on the Court. Presidents have generally selected persons who are in their late 40s or 50s, old enough to have the requisite experience yet young enough to impact the makeup of the court for decades.

Confirmation

The Appointments Clause does not tell the Senate how to assess Supreme Court nominees. As a result, the Senate has developed, and modified over time, its own set of practices and criteria for examining nominees and their fitness to serve on the bench. Nominees are, generally speaking, examined on: character and competency; social and judicial philosophy; and partypolitical identification and region (of the country from).Judiciary Committee

TheSenate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

plays a key role in the confirmation process, as nearly every Supreme Court nomination since 1868 has come before it for review. Among those not referred were the nominations of: William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, for chief Justice in 1921, and James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch, ...

, for associate justice in 1941. Byrnes is the most recent Supreme Court nominee confirmed by the Senate without being reviewed first by a committee. Under the present procedures, the committee conducts hearings, examining the background of the nominee, and questioning him or her about their work experiences, views on a variety of constitutional issues and their general judicial philosophy. The committee also hears testimony from various outside witnesses, both supporting and opposing the nomination. Among them is the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

, which since 1952 has provided its analysis and a recommendation on each nominees' professional qualifications to sit on the Supreme Court.

The committee's practice of personally interviewing nominees is a relatively recent development. The first recorded instance in which formal hearings are known to have been held on a Supreme Court nominee by a Senate committee were held by the Judiciary Committee in December 1873, on the nomination of George Henry Williams to become chief justice (after the committee had reported the nomination to the Senate with a favorable recommendation). Two days of closed-door hearings were held to review documents and hear testimony from witnesses about a controversy that had arisen about the nominee. Opposition to Williams intensified, and the president withdrew the nomination in January 1874. The committee did not hold hearings on another Supreme Court nominee until February 1916, when intense opposition arose against the nomination of Louis Brandeis to become an associate justice. There were 19 days of public hearings altogether; the Senate ultimately voted to confirm Brandeis in June 1916.

The first Supreme Court nominee to appear in person before the Judiciary Committee was Harlan F. Stone, at his own request, in January 1925 (after the committee had reported the nomination to the Senate with a favorable recommendation). Some western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

senators were concerned with his links to Wall Street and expressed their opposition when Stone was nominated. Stone proposed what was then the novelty of appearing before the Judiciary Committee to answer questions; his testimony helped secure a confirmation vote with very little opposition. The second nominee to appear before the Judiciary Committee, this time at the committee's request, was Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

in 1939, who only addressed what he considered to be slanderous allegations against him. The modern practice of the committee questioning nominees on their judicial views began with John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him ...

in 1955; the nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' decision, and several southern senators threatened to block Harlan's confirmation, hence the decision to testify. Nearly all nominees since Harlan have appeared before the Judiciary Committee. Nominees during the 1950s and through the 1970s were often questioned perfunctorily; few hearings involved extended questions and comments from committee members. They were not lengthy either, as nominees typically only spent a few hours in front of the committee.

Nominations during the late civil rights and post- Watergate eras were the beginning of the style of nomination hearings where more substantive issues were discussed. This, according to Robert Katzmann, "reflects in part the increasing importance of the Supreme Court to interest groups in the making of public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public p ...

." With this transformation have come longer confirmation hearings. In 1967, for example, Thurgood Marshall spent about seven hours in front of the committee. In 1987

File:1987 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The MS Herald of Free Enterprise capsizes after leaving the Port of Zeebrugge in Belgium, killing 193; Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashes after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Airport, ...

, Robert Bork

Robert Heron Bork (March 1, 1927 – December 19, 2012) was an American jurist who served as the solicitor general of the United States from 1973 to 1977. A professor at Yale Law School by occupation, he later served as a judge on the U.S. Cour ...

was questioned for 30 hours over five days, with the hearings as a whole lasting for 12 days. An estimated 150–300 interest groups were involved in the Bork confirmation process.

The table below notes the approximate number of hours that media sources estimate Supreme Court nominees since 2005 (excluding those whose nomination was withdrawn) have spent before the Senate Judiciary Committee for public testimony.

At the close of hearings, the committee votes on whether a nomination should go to the full Senate. Historically, it sends nominations with a favorable or unfavorable report or with no recommendation. It has been the committee's typical practice to report even those nominations that were opposed by a committee majority. The most recent nominee to be reported ''unfavorably'' was Robert Bork in 1987. In 1991

File:1991 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Boris Yeltsin, elected as Russia's first president, waves the new flag of Russia after the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, orchestrated by Soviet hardliners; Mount Pinatubo erupts in the Phi ...

, the nomination of Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

was forwarded to the full Senate ''without recommendation'' after an earlier vote to give the nomination a ''favorable recommendation'' resulted in a tie.

Without an affirmative vote, a nomination cannot proceed to the floor of the Senate, that is unless the Senate votes to discharge it from the committee. This rarely needed parliamentary procedure was used to move the nomination in 2022 of Ketanji Brown Jackson

Ketanji Onyika Brown Jackson ( ; born September 14, 1970) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Jackson was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Joe Biden on February 25, 202 ...

forward, when the committee deadlocked along party lines in a vote on whether to give it a favorable recommendation.

Full Senate

Once the committee reports out the nomination, it is put before the full Senate for final consideration. A simple majority vote is required to confirm or to reject a nominee. Historically, such rejections are relatively uncommon. Of the 37 unsuccessful Supreme Court nominations since 1789, only 11 nominees have been rejected in a Senate roll-call vote. The most recent rejection of a nominee by vote of the full Senate occurred in 1987, when it defeated Robert Bork's nomination by a 42–58 vote. Senate debate on a nomination continues until ended bycloture

Cloture (, also ), closure or, informally, a guillotine, is a motion or process in parliamentary procedure aimed at bringing debate to a quick end. The cloture procedure originated in the French National Assembly, from which the name is taken. ' ...

, which allows debate to end and forces a final vote. Historically, a three-fifths majority (60%) had to vote in favor of cloture in order to move to a final vote on a Supreme Court nominee. In 1968, there was a bi-partisan

Bipartisanship, sometimes referred to as nonpartisanship, is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system (especially those of the United States and some other western countries), in which opposing political parties find co ...

effort to filibuster the nomination of incumbent

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

associate justice Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from R ...

as chief justice. After four days of debate, a cloture motion fell short of the necessary two-thirds majority to cut off debate. President Lyndon Johnson withdrew the nomination soon afterward. Fortas remained on the Court as an associate justice. More recently, in 2017

File:2017 Events Collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: The War Against ISIS at the Battle of Mosul (2016-2017); aftermath of the Manchester Arena bombing; The Solar eclipse of August 21, 2017 ("Great American Eclipse"); North Korea tests a s ...

, there was an effort to filibuster President Donald Trump's nomination of Neil Gorsuch. Unlike the Fortas filibuster, however, only Democratic senators voted against cloture. The Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

majority responded by changing the standing rules to allow for filibusters of Supreme Court nominations to be broken with simple majority rather than three-fifths. The vote threshold for cloture on nominations to lower court and executive branch positions had earlier been lowered to simple majority. That change was made in 2013, when the Democrats held the majority.

A president has the prerogative to withdraw a nomination at any point during the process, typically doing so if it becomes clear that the Senate will reject the nominee. This occurred most recently with President George W. Bush's nomination of Harriet Miers in 2005 to succeed Sandra Day O'Connor, who had announced her intention to retire. The nomination was never fully embraced by the president's own (Republican) party, and Bush withdrew it before Committee hearings had begun. Bush had previously nominated John Roberts

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and jurist who has served as the 17th chief justice of the United States since 2005. Roberts has authored the majority opinion in several landmark cases, including '' Nat ...

to succeed O'Connor, but upon the death of William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

, that initial nomination was withdrawn and resubmitted as a nomination for Chief Justice, for which he was confirmed. O'Connor was ultimately succeeded by Samuel Alito.

The Judiciary Committee has the prerogative to take no action on a nomination. For example, it did not act upon President Dwight Eisenhower's first nomination of John Marshall Harlan II in November 1954, as it was made one month prior to the adjournment of the 83rd Congress. Most recently, the committee, led at the time by Republicans, did not hold hearings on Democratic President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

's 2016 nomination of Merrick Garland. Citing the upcoming 2016 presidential election

This national electoral calendar for 2016 lists the national/ federal elections held in 2016 in all sovereign states and their dependent territories. By-elections are excluded, though national referendums are included.

January

*7 January: Kiri ...

and Obama's Lame duck status, Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding t ...

Mitch McConnell declared at the time that the vacancy should be filled by the next president. The vacancy, created by the death of Antonin Scalia, arose 269 days before the election. The nomination expired in January 2017, at the end of the 114th Congress.

Similarly, the Senate has the prerogative to take no action on a nomination, or to table

Table may refer to:

* Table (furniture), a piece of furniture with a flat surface and one or more legs

* Table (landform), a flat area of land

* Table (information), a data arrangement with rows and columns

* Table (database), how the table data ...

it, effectively eliminating any prospect of the person's confirmation. Though frequently attempted over the years, a successful vote to table a nomination has been a rare occurrence. Even so, this procedure was successfully used to block several nominees of presidents John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

(1841–1845) and Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

(1850–1853). In modern time, the decision in 2016 by Senate leadership to take no action on the Garland nomination was unique, and received significant push back from scholars and in public opinion challenging whether their refusal to meaningfully consider a duly nominated and well qualified individual contravened their Appointments Clause responsibility to "advise and consent".

Under Senate rules, nominations still pending when the Senate adjourns at the end of a session or recesses for more than 30 days are returned to the president unless the Senate, by

Under Senate rules, nominations still pending when the Senate adjourns at the end of a session or recesses for more than 30 days are returned to the president unless the Senate, by unanimous consent

In parliamentary procedure, unanimous consent, also known as general consent, or in the case of the parliaments under the Westminster system, leave of the house (or leave of the senate), is a situation in which no member present objects to a prop ...

, waives the rule. If the president still desires Senate consideration of a returned nomination, he or she must submit a new nomination when the Senate returns in the new session or following its extended recess. Eisenhower re-nominated John Harlan in January 1955, when the new Congress convened. Obama's successor, Donald Trump, nominated Neil Gorsuch to fill the Scalia vacancy shortly after his inauguration.

Once the Senate has taken final action on a nomination, the secretary of the Senate attests to a resolution of confirmation or rejection and sends it to the president. After receiving a resolution of confirmation, the president may then sign and deliver a commission officially appointing the nominee to the Court. The appointee then must take two oaths before executing the duties of the office: the constitutional oath, which is used for every federal and state officeholder below the president, and the judicial oath used for all federal judges. The general practice in recent decades has been to hold the oath ceremony at either the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

or the Supreme Court Building. It is at this point that a person has taken "the necessary steps toward becoming a member of the Court."

Recess appointments

Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution empowers the president to fill critical federal executive and judicial branch vacancies unilaterally but temporarily when the Senate is in recess, and thus unavailable to provide advice and consent. Such

Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution empowers the president to fill critical federal executive and judicial branch vacancies unilaterally but temporarily when the Senate is in recess, and thus unavailable to provide advice and consent. Such recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

s, including to the Supreme Court, expire at the end of the next Senate session. To continue to serve thereafter, the appointee must be formally nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Through the late 1800s, the Senate was in recess for long periods of time, and so this clause enabled the president to keep the functions of government running in the meantime, but without completely bypassing the system of checks and balances. As the Senate now remains in session nearly year-round, this recess appointment power has lost its original necessity and usefulness.

There have been 12 recess appointments to the Supreme Court altogether. George Washington made two: Thomas Johnson in August 1791, and John Rutledge in July 1795. Rutledge is the only recess-appointed justice not subsequently confirmed by the Senate, rejected December 1795. Later, during the 1800s, seven presidents made one recess appointment each. More recently, Dwight D. Eisenhower made three: Earl Warren in October 1953, William J. Brennan Jr. in October 1956, and Potter Stewart in October 1958. No president since has made a recess appointment to the Supreme Court. In 1960 the Senate passed a non-binding resolution stating that it was the sense of the Senate that recess appointments to the Supreme Court should not be made except under unusual circumstances.

Partisanship and the confirmation process

Though Supreme Court nominations have historically been intertwined with the political battles of the day, there is a perception that the confirmation process has become more partisan over the past several decades. The 1987 battle over Robert Bork's nomination is viewed as a pivotal event in the present day politicization of the Supreme Court nomination and confirmation process. The subsequent contentious confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas andBrett Kavanaugh

Brett Michael Kavanaugh ( ; born February 12, 1965) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018, and has served since ...

, in 1991 and 2018

File:2018 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The 2018 Winter Olympics opening ceremony in PyeongChang, South Korea; Protests erupt following the Assassination of Jamal Khashoggi; March for Our Lives protests take place across the Unit ...

respectively, along with the Senate's refusal to consider the nomination of Merrick Garland in 2016, underscored the breadth of the partisan divide. Much of the proceedings around the hearings for Ketanji Brown Jackson in 2022 focused on those prior battles and which party should be blamed for politicizing the confirmation process.

The widening of the partisan divide over judicial nominations corresponds with the prolongation of the confirmation process. From the establishment of the Supreme Court up to the early 1950s, the process of approving justices was usually rapid. The average time between nomination and confirmation was 13.2 days. Eight justices during that era were confirmed on the same day they were formally nominated, including

The widening of the partisan divide over judicial nominations corresponds with the prolongation of the confirmation process. From the establishment of the Supreme Court up to the early 1950s, the process of approving justices was usually rapid. The average time between nomination and confirmation was 13.2 days. Eight justices during that era were confirmed on the same day they were formally nominated, including Edward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White Jr. (November 3, 1844 – May 19, 1921) was an American politician and jurist from Louisiana. White was a U.S. Supreme Court justice for 27 years, first as an associate justice from 1894 to 1910, then as the ninth chief ...

as an associate justice in 1894 and again as chief justice in 1910, and on a voice vote

In parliamentary procedure, a voice vote (from the Latin ''viva voce'', meaning "live voice") or acclamation is a voting method in deliberative assemblies (such as legislatures) in which a group vote is taken on a topic or motion by responding vo ...

both times. From the mid-1950s to 2020, however, the process took much longer. Over the past 65 years, the time from nomination to confirmation has averaged 54.4 days.

The partisan divide over judicial nominations can also be seen in both the referral and the confirmation vote margins received by nominees over the past few decades. Since the 1990s, the votes by which the Judiciary Committee refers nominations to the full Senate have frequently fallen along party lines. The most recent nomination forwarded with a unanimous bipartisan recommendation was that of Stephen Breyer in 1994. More recently, the 2020 nomination of Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. ...

was forwarded with a unanimous recommendation, but only because all the committee's Democrats boycotted the proceedings. Likewise, confirmation votes are increasingly falling nearly along party lines. The last justice to be confirmed by a unanimous vote was Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

, 97–0, in 1988; the last to receive a two-thirds majority 2/3 may refer to:

* A fraction with decimal value 0.6666...

* A way to write the expression "2 ÷ 3" ("two divided by three")

* 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines of the United States Marine Corps

* February 3

* March 2

Events Pre-1600

* 537 – ...

was Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

, 68–31, in 2009. The Senate voted to confirm Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 by a razor-thin 50–48–1 (51.02% favorable) margin that broke along party lines.

Tenure and vacancies

Tenure

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

via the impeachment process. The Framers of the Constitution chose good behavior tenure to limit the power to remove justices and to ensure judicial independence. The only justice ever to be impeached was Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of t ...

in 1804, after he openly criticized President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

and his policies to a Baltimore grand jury. The House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

adopted eight articles of impeachment against Chase; however, he was acquitted by the Senate, and remained in office until his death in 1811. This failed impeachment was, according to William Rehnquist, "enormously important in securing the kind of judicial independence contemplated by" the Constitution. No subsequent effort to impeach a sitting justices has progressed beyond referral to the Judiciary Committee. William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

was the subject of hearings twice, in 1953 and again in 1970, and Abe Fortas resigned while hearings were being organized in 1969.

Vacancies

The ability of a president to appoint a new justice depends on the occurrence of a vacancy on the Court. Because justices have indefinite tenure, vacancies, and thus appointments, occur unevenly. Sometimes vacancies arise in quick succession. The shortest period of time between vacancies occurred in September 1971, when Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II left within days of each other. On the other hand, sometimes several years pass between vacancies. The longest period of time between vacancies was 12 years, from 1811 to 1823 (from the death of Samuel Chase to the death of Henry Brockholst Livingston). The next longest was an 11-year span, from 1994 to 2005 (from the retirement of Harry Blackmun to the death of William Rehnquist). On average a new justice joins the Court about every two years. Variables such as age, tenure, health, potential longevity and personal finances impact retirement decisions, as do considerations about whether the incumbent president—who would appoint their successor were they to retire—shares their legal-policy preferences. Due to the randomness of vacancies, some presidents had several opportunities to make many Supreme Court appointments, while others had few or even none. George Washington made 14 nominations, 10 of which were confirmed, during his two terms in office, and Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed eight justices within a six year period during his second and third terms, while William Howard Taft made six appointments during his single term. OnlyWilliam Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, Andrew Johnson and Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

did not have a nominee confirmed. Carter is the only one of the four who served a full term in office.

It was not unusual, historically, for justices to die while still on the bench. Specifically, 38 of the 57 justices (two-thirds) appointed prior to 1900 died in office. But since that time it has been less frequent for vacancies on the Court to be created by the death of a justice – about one third. The most recent justice to die while in office was Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by Presiden ...

in 2020.

Since the mid-1950s, most justices (80%) have left office through (resigning into) retirement. Beginning in 1869, qualifying justices have been able to retire on a pension; currently any justice who is 65 and has served 15 years on the bench can retire with a full salary. In contrast, resignation prior to retirement eligibility is rare. The last non-retirement resignation from the Court was that of Abe Fortas in 1969.

When a chief justice vacancy occurs, the president may choose to nominate an

When a chief justice vacancy occurs, the president may choose to nominate an incumbent

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

associate justice for the Court's top post. If the chief justice nominee is confirmed, he or she must resign as an associate justice to assume the new position. The president then selects a new nominee to fill the now-vacant associate justice seat. Three persons have served as Associate Justice and then as Chief Justice without break between their periods of service: Edward Douglas White; Harlan F. Stone; and William Rehnquist.

Additionally, because the Constitution does not specify the size of the Court, Congress may determine the matter through law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

. If Congress were to increase the size of the Court, the president would then have an opportunity to nominate a person (or persons) to the new seat(s). Congress has increased the size of the Court on five occasions; on two other occasions it has reduced the Court's size.

There has been considerable variation in the duration of Supreme Court vacancies since the first occurred in 1791. Vacancies on the Court generally lasted for longer periods of time prior to the 20th century. In fact, vacancies prior to 1900 lasted an average of 165 days, which is more than twice the average length of vacancies since 1900. The average duration of the 10 Supreme Court vacancies since 1991—from a justice's departure date to the swearing-in of their successor—has been 70 days. Three of these vacancies lasted for less than a day each, as the successor was sworn in the same day the retiring justice officially left office. The longest vacancy during this time frame, and the longest since the Supreme Court was expanded to nine members in 1869, was the 422-day vacancy between the death of Antonin Scalia on February 13, 2016 and the swearing-in of Neil Gorsuch on April 10, 2017. Overall, it was the eighth-longest vacancy period in U.S. Supreme Court history. The longest vacancy lasted days, from the death on April 21, 1844 of Henry Baldwin until August 10, 1846, when Robert C. Grier was sworn into office to replace him.

See also

*List of nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest ranking judicial body in the United States. Established by Article III of the Constitution, the Court was organized by the 1st United States Congress through the Judiciary Act of 1789, whic ...

* List of positions filled by presidential appointment with Senate confirmation

* '' NLRB v. Noel Canning'', a 2014 U.S. Supreme Court case regarding the president's recess appointment authority

Notes

References

External links

Supreme Court Nominations Research Guide

Georgetown University Law Library.

Supreme Court of the United States

website

United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

website {{Nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court