Newgate prison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Newgate Prison was a

In the early 12th century, Henry II instituted legal reforms that gave the Crown more control over the administration of justice. As part of his Assize of Clarendon of 1166, he required the construction of prisons, where the accused would stay while royal judges debated their innocence or guilt and subsequent punishment. In 1188, Newgate was the first institution established to meet that purpose.

A few decades later in 1236, in an effort to significantly enlarge the prison, the king converted one of the Newgate turrets, which still functioned as a main gate into the city, into an extension of the prison. The addition included new dungeons and adjacent buildings, which would remain unaltered for roughly two centuries.

By the 15th century, however, Newgate was in need of repair. Following pressure from reformers who learned that the women's quarters were too small and did not contain their own latrines – obliging women to walk through the men's quarters to reach one – officials added a separate tower and chamber for female prisoners in 1406. Some Londoners bequeathed their estates to repair the prison. The building was collapsing and decaying, and many prisoners were dying from the close quarters, overcrowding, rampant disease, and bad sanitary conditions. Indeed, one year, 22 prisoners died from " gaol fever". The situation in Newgate was so dire that in 1419, city officials temporarily shut down the prison.

The

In the early 12th century, Henry II instituted legal reforms that gave the Crown more control over the administration of justice. As part of his Assize of Clarendon of 1166, he required the construction of prisons, where the accused would stay while royal judges debated their innocence or guilt and subsequent punishment. In 1188, Newgate was the first institution established to meet that purpose.

A few decades later in 1236, in an effort to significantly enlarge the prison, the king converted one of the Newgate turrets, which still functioned as a main gate into the city, into an extension of the prison. The addition included new dungeons and adjacent buildings, which would remain unaltered for roughly two centuries.

By the 15th century, however, Newgate was in need of repair. Following pressure from reformers who learned that the women's quarters were too small and did not contain their own latrines – obliging women to walk through the men's quarters to reach one – officials added a separate tower and chamber for female prisoners in 1406. Some Londoners bequeathed their estates to repair the prison. The building was collapsing and decaying, and many prisoners were dying from the close quarters, overcrowding, rampant disease, and bad sanitary conditions. Indeed, one year, 22 prisoners died from " gaol fever". The situation in Newgate was so dire that in 1419, city officials temporarily shut down the prison.

The  In 1769, construction was begun by the King's Master Mason,

In 1769, construction was begun by the King's Master Mason,

All manner of criminals stayed at Newgate. Some committed acts of petty crime and theft, breaking and entering homes or committing highway robberies, while others performed serious crimes such as rapes and murders. The number of prisoners in Newgate for specific types of crime often grew and fell, reflecting public anxieties of the time. For example, towards the tail end of Edward I's reign, there was a rise in street robberies. As such, the punishment for drawing out a dagger was 15 days in Newgate; injuring someone meant 40 days in the prison.

Upon their arrival in Newgate, prisoners were chained and led to the appropriate dungeon for their crime. Those who had been sentenced to death stayed in a cellar beneath the keeper's house, essentially an open sewer lined with chains and shackles to encourage submission. Otherwise, common debtors were sent to the "stone hall" whereas common felons were taken to the "stone hold". The dungeons were dirty and unlit, so depraved that physicians would not enter.

The conditions did not improve with time. Prisoners who could afford to purchase alcohol from the prisoner-run drinking cellar by the main entrance to Newgate remained perpetually drunk. There were lice everywhere, and jailers left the prisoners chained to the wall to languish and starve. The legend of the " Black Dog", an emaciated spirit thought to represent the brutal treatment of prisoners, only served to emphasize the harsh conditions. From 1315 to 1316, 62 deaths in Newgate were under investigation by the coroner, and prisoners were always desperate to leave the prison.

The cruel treatment from guards did nothing to help the unfortunate prisoners. According to medieval statute, the prison was to be managed by two annually elected

All manner of criminals stayed at Newgate. Some committed acts of petty crime and theft, breaking and entering homes or committing highway robberies, while others performed serious crimes such as rapes and murders. The number of prisoners in Newgate for specific types of crime often grew and fell, reflecting public anxieties of the time. For example, towards the tail end of Edward I's reign, there was a rise in street robberies. As such, the punishment for drawing out a dagger was 15 days in Newgate; injuring someone meant 40 days in the prison.

Upon their arrival in Newgate, prisoners were chained and led to the appropriate dungeon for their crime. Those who had been sentenced to death stayed in a cellar beneath the keeper's house, essentially an open sewer lined with chains and shackles to encourage submission. Otherwise, common debtors were sent to the "stone hall" whereas common felons were taken to the "stone hold". The dungeons were dirty and unlit, so depraved that physicians would not enter.

The conditions did not improve with time. Prisoners who could afford to purchase alcohol from the prisoner-run drinking cellar by the main entrance to Newgate remained perpetually drunk. There were lice everywhere, and jailers left the prisoners chained to the wall to languish and starve. The legend of the " Black Dog", an emaciated spirit thought to represent the brutal treatment of prisoners, only served to emphasize the harsh conditions. From 1315 to 1316, 62 deaths in Newgate were under investigation by the coroner, and prisoners were always desperate to leave the prison.

The cruel treatment from guards did nothing to help the unfortunate prisoners. According to medieval statute, the prison was to be managed by two annually elected

In 1783, the site of London's gallows was moved from Tyburn to Newgate. Public executions outside the prison – by this time, London's main prison – continued to draw large crowds. It was also possible to visit the prison by obtaining a permit from the Lord Mayor of the City of London or a

In 1783, the site of London's gallows was moved from Tyburn to Newgate. Public executions outside the prison – by this time, London's main prison – continued to draw large crowds. It was also possible to visit the prison by obtaining a permit from the Lord Mayor of the City of London or a

Newgate prison

Prison History Database: Newgate Prison

Newgate prison

The Diary of Thomas Lloyd kept in Newgate Prison, 1794–1796

{{Coord, 51, 30, 56.49, N, 0, 06, 06.91, W, region:GB_type:landmark, display=title 1188 establishments in England Buildings and structures demolished in 1777 Defunct prisons in London Former buildings and structures in the City of London Demolished buildings and structures in London Debtors' prisons Demolished prisons Buildings and structures demolished in 1904 Windmills in London

prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

London Wall

The London Wall was a defensive wall first built by the Romans around the strategically important port town of Londinium in AD 200, and is now the name of a modern street in the City of London. It has origins as an initial mound wall and ...

. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, the prison was extended and rebuilt many times, and remained in use for over 700 years, from 1188 to 1902.

For much of its history, a succession of criminal courtrooms were attached to the prison, commonly referred to as the "Old Bailey". The present Old Bailey (officially, Central Criminal Court) now occupies much of the site of the prison.

In the late 1700s, executions by hanging were moved here from the Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and sout ...

gallows. These took place on the public street in front of the prison, drawing crowds until 1868, when they were moved into the prison.

History

In the early 12th century, Henry II instituted legal reforms that gave the Crown more control over the administration of justice. As part of his Assize of Clarendon of 1166, he required the construction of prisons, where the accused would stay while royal judges debated their innocence or guilt and subsequent punishment. In 1188, Newgate was the first institution established to meet that purpose.

A few decades later in 1236, in an effort to significantly enlarge the prison, the king converted one of the Newgate turrets, which still functioned as a main gate into the city, into an extension of the prison. The addition included new dungeons and adjacent buildings, which would remain unaltered for roughly two centuries.

By the 15th century, however, Newgate was in need of repair. Following pressure from reformers who learned that the women's quarters were too small and did not contain their own latrines – obliging women to walk through the men's quarters to reach one – officials added a separate tower and chamber for female prisoners in 1406. Some Londoners bequeathed their estates to repair the prison. The building was collapsing and decaying, and many prisoners were dying from the close quarters, overcrowding, rampant disease, and bad sanitary conditions. Indeed, one year, 22 prisoners died from " gaol fever". The situation in Newgate was so dire that in 1419, city officials temporarily shut down the prison.

The

In the early 12th century, Henry II instituted legal reforms that gave the Crown more control over the administration of justice. As part of his Assize of Clarendon of 1166, he required the construction of prisons, where the accused would stay while royal judges debated their innocence or guilt and subsequent punishment. In 1188, Newgate was the first institution established to meet that purpose.

A few decades later in 1236, in an effort to significantly enlarge the prison, the king converted one of the Newgate turrets, which still functioned as a main gate into the city, into an extension of the prison. The addition included new dungeons and adjacent buildings, which would remain unaltered for roughly two centuries.

By the 15th century, however, Newgate was in need of repair. Following pressure from reformers who learned that the women's quarters were too small and did not contain their own latrines – obliging women to walk through the men's quarters to reach one – officials added a separate tower and chamber for female prisoners in 1406. Some Londoners bequeathed their estates to repair the prison. The building was collapsing and decaying, and many prisoners were dying from the close quarters, overcrowding, rampant disease, and bad sanitary conditions. Indeed, one year, 22 prisoners died from " gaol fever". The situation in Newgate was so dire that in 1419, city officials temporarily shut down the prison.

The executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

s of the will of Lord Mayor Dick Whittington were granted a licence to renovate the prison in 1422. The gate and gaol were pulled down and rebuilt. There was a new central hall for meals, a new chapel, and the creation of additional chambers and basement cells with no light or ventilation. There were three main wards: the Master's side for those could afford to pay for their own food and accommodations, the Common side for those who were too poor, and a Press Yard for special prisoners. The king often used Newgate as a holding place for heretics, traitors, and rebellious subjects brought to London for trial. The prison housed both male and female felons and debtors. Prisoners were separated into wards by sex. By the mid-15th century, Newgate could accommodate roughly 300 prisoners. Though the prisoners lived in separate quarters, they mixed freely with each other and visitors to the prison.

The prison was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, and was rebuilt in 1672 by Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

. In 1752, a windmill was built on top of the prison by Stephen Hales in an effort to provide ventilation.

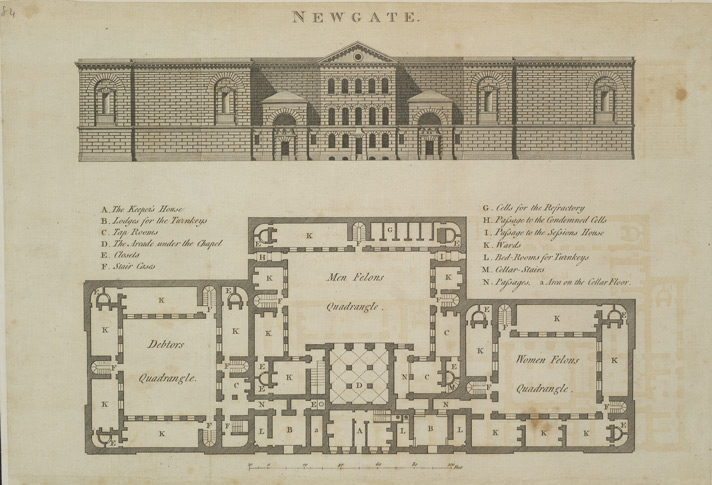

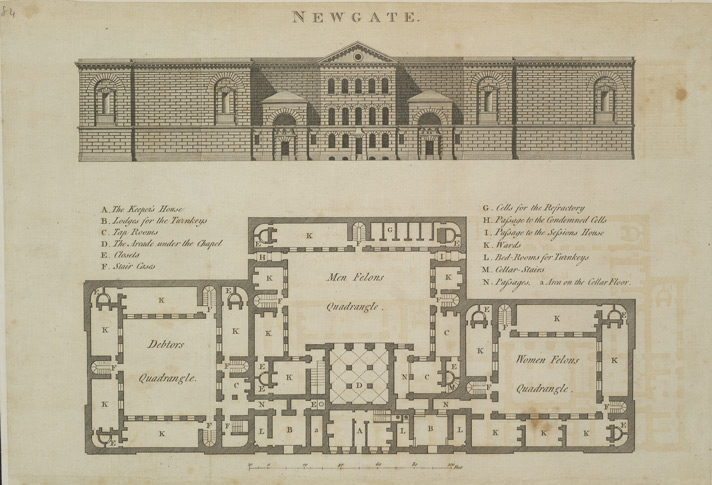

In 1769, construction was begun by the King's Master Mason,

In 1769, construction was begun by the King's Master Mason, John Deval

John Deval (1701–1774) was an 18th-century British sculptor and Master Mason, as was his namesake son (1728–1794). He was Chief Mason to the Crown and was the mason for the Tower of London and Royal Mews.

Life

He was born in Eynsham in Oxf ...

, to enlarge the prison and add a new sessions house. Parliament granted £50,000 (~£9.3 million in 2020 terms) towards the cost, and the City of London provided land measuring by . The work followed the designs of George Dance the Younger. The new prison was constructed to an ''architecture terrible

' was an architectural style advocated by French architect Jacques-François Blondel in his nine-volume treatise ' (1771–77). Blondel promoted the style for the exterior design of prisons: the form of the building itself would proclaim its fun ...

'' design intended to discourage law-breaking. The building was laid out around a central courtyard, and was divided into two sections: a "Common" area for poor prisoners and a "State area" for those able to afford more comfortable accommodation.

Construction of the second Newgate Prison was almost finished when it was stormed by a mob during the Gordon riots in June 1780. The building was gutted by fire, and the walls were badly damaged; the cost of repairs was estimated at £30,000 (~£5.6 million in 2020 terms). Dance's new prison was finally completed in 1782.

During the early 19th century, the prison attracted the attention of the social reformer Elizabeth Fry. She was particularly concerned at the conditions in which female prisoners (and their children) were held. After she presented evidence to the House of Commons improvements were made.

The prison closed in 1902, and was demolished in 1903.

Prison life

All manner of criminals stayed at Newgate. Some committed acts of petty crime and theft, breaking and entering homes or committing highway robberies, while others performed serious crimes such as rapes and murders. The number of prisoners in Newgate for specific types of crime often grew and fell, reflecting public anxieties of the time. For example, towards the tail end of Edward I's reign, there was a rise in street robberies. As such, the punishment for drawing out a dagger was 15 days in Newgate; injuring someone meant 40 days in the prison.

Upon their arrival in Newgate, prisoners were chained and led to the appropriate dungeon for their crime. Those who had been sentenced to death stayed in a cellar beneath the keeper's house, essentially an open sewer lined with chains and shackles to encourage submission. Otherwise, common debtors were sent to the "stone hall" whereas common felons were taken to the "stone hold". The dungeons were dirty and unlit, so depraved that physicians would not enter.

The conditions did not improve with time. Prisoners who could afford to purchase alcohol from the prisoner-run drinking cellar by the main entrance to Newgate remained perpetually drunk. There were lice everywhere, and jailers left the prisoners chained to the wall to languish and starve. The legend of the " Black Dog", an emaciated spirit thought to represent the brutal treatment of prisoners, only served to emphasize the harsh conditions. From 1315 to 1316, 62 deaths in Newgate were under investigation by the coroner, and prisoners were always desperate to leave the prison.

The cruel treatment from guards did nothing to help the unfortunate prisoners. According to medieval statute, the prison was to be managed by two annually elected

All manner of criminals stayed at Newgate. Some committed acts of petty crime and theft, breaking and entering homes or committing highway robberies, while others performed serious crimes such as rapes and murders. The number of prisoners in Newgate for specific types of crime often grew and fell, reflecting public anxieties of the time. For example, towards the tail end of Edward I's reign, there was a rise in street robberies. As such, the punishment for drawing out a dagger was 15 days in Newgate; injuring someone meant 40 days in the prison.

Upon their arrival in Newgate, prisoners were chained and led to the appropriate dungeon for their crime. Those who had been sentenced to death stayed in a cellar beneath the keeper's house, essentially an open sewer lined with chains and shackles to encourage submission. Otherwise, common debtors were sent to the "stone hall" whereas common felons were taken to the "stone hold". The dungeons were dirty and unlit, so depraved that physicians would not enter.

The conditions did not improve with time. Prisoners who could afford to purchase alcohol from the prisoner-run drinking cellar by the main entrance to Newgate remained perpetually drunk. There were lice everywhere, and jailers left the prisoners chained to the wall to languish and starve. The legend of the " Black Dog", an emaciated spirit thought to represent the brutal treatment of prisoners, only served to emphasize the harsh conditions. From 1315 to 1316, 62 deaths in Newgate were under investigation by the coroner, and prisoners were always desperate to leave the prison.

The cruel treatment from guards did nothing to help the unfortunate prisoners. According to medieval statute, the prison was to be managed by two annually elected sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

s, who in turn would sublet the administration of the prison to private "gaolers", or "keepers", for a price. These keepers in turn were permitted to exact payment directly from the inmates, making the position one of the most profitable in London. Inevitably, often the system offered incentives for the keepers to exhibit cruelty to the prisoners, charging them for everything from entering the gaol to having their chains both put on and taken off. They often began inflicting punishment on prisoners before their sentences even began. Guards, whose incomes partially depended on extorting their wards, charged the prisoners for food, bedding, and to be released from their shackles. To earn additional money, guards blackmailed and tortured prisoners. Among the most notorious Keepers in the Middle Ages were the 14th-century gaolers Edmund Lorimer, who was infamous for charging inmates four times the legal limit for the removal of irons, and Hugh De Croydon, who was eventually convicted of blackmailing prisoners in his care.

Indeed, the list of things that prison guards were not allowed to do serve as a better indication of the conditions in Newgate than the list of things that they were allowed to do. Gaolers were not allowed to take alms intended for prisoners. They could not monopolize the sale of food, charge excessive fees for beds, or demand fees for bringing prisoners to the Old Bailey. In 1393, new regulation was added to prevent gaolers from charging for lamps or beds.

Not a half century later, in 1431, city administrators met to discuss other potential areas of reform. Proposed regulations included separating freemen and freewomen into the north and south chambers, respectively, and keeping the rest of the prisoners in underground holding cells. Good prisoners who had not been accused of serious crimes would be allowed to use the chapel and recreation rooms at no additional fees. Meanwhile, debtors whose burden did not meet a minimum threshold would not be required to wear shackles. Prison officials were barred from selling food, charcoal, and candles. The prison was supposed to have yearly inspections, but whether they actually occurred is unknown. Other reforms attempted to reduce the waiting time between jail deliveries to the Old Bailey, with the aim of reducing suffering, but these efforts had little effect.

Over the centuries, Newgate was used for a number of purposes including imprisoning people awaiting execution, although it was not always secure: burglar Jack Sheppard twice escaped from the prison before he went to the gallows at Tyburn in 1724. Prison chaplain Paul Lorrain achieved some fame in the early 18th century for his sometimes dubious publication of '' Confessions'' of the condemned.

Executions

In 1783, the site of London's gallows was moved from Tyburn to Newgate. Public executions outside the prison – by this time, London's main prison – continued to draw large crowds. It was also possible to visit the prison by obtaining a permit from the Lord Mayor of the City of London or a

In 1783, the site of London's gallows was moved from Tyburn to Newgate. Public executions outside the prison – by this time, London's main prison – continued to draw large crowds. It was also possible to visit the prison by obtaining a permit from the Lord Mayor of the City of London or a sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

. The condemned were kept in narrow, sombre cells separated from Newgate Street by a thick wall and received only a dim light from the inner courtyard. The gallows were constructed outside a door in Newgate Street for public viewing. Dense crowds of thousands of spectators could pack the streets to see these events, and in 1807 dozens died at a public execution when part of the crowd of 40,000 spectators collapsed into a human crush.

From 1868, public executions were discontinued and executions were carried out on gallows inside Newgate, initially using the same mobile gallows in the Chapel Yard, but later in a shed built near the same spot. Dead Man's Walk was a long stone-flagged passageway, partly open to the sky and roofed with iron mesh (thus also known as Birdcage Walk). The bodies of the executed criminals were then buried beneath its flagstones.

Until the 20th century, future British executioners were trained at Newgate. One of the last was John Ellis, who began training in 1901.

In total – publicly or otherwise – 1,169 people were executed at the prison. In November 1835 James Pratt and John Smith

James Pratt (1805–1835), also known as John Pratt, and John Smith (1795–1835) were two London men who, in November 1835, became the last two to be executed for sodomy in England.Cook ''et al'' (2007), p. 109. Pratt and Smith were arrested in ...

were the last two men to be executed for sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''s ...

. Michael Barrett was the last man to be hanged in public outside Newgate Prison (and the last person to be publicly executed in Great Britain) on 26 May 1868.

Notable prisoners

Other famous prisoners at Newgate include: * Thomas Bambridge, warden of Fleet Prison in the 1720s – imprisoned forextortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, ...

and murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the ...

* George Barrington, pickpocket – held at least twice in Newgate between 1783 and 1790, before transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...

to Australia

* John Bellingham, assassin of the Prime Minister Spencer Perceval 1812 – hanged in 1812

* John Bernardi

Major John Bernardi (1657 – 20 September 1736) was an English soldier, adventurer and Jacobite conspirator. Bernardi is best known for his involvement in an assassination plot against William III, and his subsequent forty-year imprisonment, w ...

, soldier and Jacobite conspirator – imprisoned without trial in Newgate for forty years

* Robert Blackbourn

Robert Blackbourn or BlackburneSources spell his surname variously as Blackbourn, Blackbourne, Blackburne or Blackburn. (died 1748) was an English Jacobite conspirator arrested for his involvement in an assassination plot of 1696.

Suspected of p ...

, Jacobite conspirator – imprisoned without trial in Newgate for fifty years

* John Bradford, religious reformer – burned at the stake at Newgate in 1555

* Giacomo Casanova, Venetian libertine – imprisoned for alleged bigamy

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. ...

* Ellis Casper, who helped to perpetrate the 1839 Gold Dust Robbery – held in Newgate before being transported to Van Diemen's Land in 1841

* Elizabeth Cellier

Elizabeth Cellier, commonly known as Mrs. Cellier or 'Popish Midwife' (c. 1668 – c. 1688), was a notable Catholic midwife in seventeenth-century England. She stood trial for treason in 1679 for her alleged part in the 'Meal-Tub Plot' against ...

, also known as the "Popish Midwife", midwife

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their lifespan; ...

– incarcerated in 1679–1680 during a high treason trial for the alleged "Meal-Tub Plot"

* William Chaloner, currency counterfeiter and con artist – imprisoned multiple times at Newgate between 1696 and his hanging 1699 for high treason

* Marcy Clay, thief and highwayrobber who dressed as a man, died by suicide before she could be hanged in April 1665

* William Cobbett, Parliamentary reformer and agrarian – imprisoned 1810–1812 for treasonous libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defi ...

* Thomas Neill Cream

Thomas Neill Cream (27 May 1850 – 15 November 1892), also known as the Lambeth Poisoner, was a Scottish-Canadian medical doctor and serial killer who poisoned his victims with strychnine. Over the course of his career, he murdered up t ...

, doctor and blackmailer – tried, convicted, and hanged in 1892 for poisoning several of his patients as the "Lambeth Poisoner"

* Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

, author of '' Robinson Crusoe'' and ''Moll Flanders

''Moll Flanders'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. It purports to be the true account of the life of the eponymous Moll, detailing her exploits from birth until old age.

By 1721, Defoe had become a recognised novelist, wi ...

'' (whose protagonist is born and imprisoned in Newgate Prison) – held at Newgate in 1703 for seditious libel

* Claude Du Vall

Claude Du Vall (or Duval) (164321 January 1670) was a French highwayman in Restoration England. He came from a family of decayed nobility, and worked in the service of exiled royalists who returned to England under King Charles II. Little els ...

, highwayman – held in Newgate from December 1669 until his execution in January 1670

* Amelia Dyer (1837–1896), known as the "Reading baby farmer" – serial killer, hanged 10 June 1896

* Daniel Eaton, author and activist – imprisoned in 1812–1813 for atheism and blasphemous libel; the subject of the defence offered by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achi ...

in his essay, '' A Letter to Lord Ellenborough''

* John Frith, Protestant priest and martyr – held at Newgate in 1533 before burning at the stake

* Mary Frith, alias "Moll Cutpurse", pickpocket and fence in the 1600s – in Newgate multiple times for multiple offenses

* Lord George Gordon, UK politician after whom the Gordon Riots are named – died of typhoid in 1793 in Newgate

* Jack Hall – a petty thief executed 1707 remembered only on account of his Gallows Confessional becoming a memorable folk song made popular with the adaptation Sam Hall by English comic minstrel, C.W. Ross.

* Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

, playwright and poet – imprisoned for killing fellow actor Gabriel Spenser in a 1598 duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and ...

; freed by pleading benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy (Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

* Jørgen Jørgensen

Jørgen Jørgensen (name of birth: Jürgensen, and changed to Jorgenson from 1817)Wilde, W H, ''Oxford Companion to Australian Literature'' 2nd ed. (29 March 1780 – 20 January 1841) was a Danish adventurer during the Age of Revolution. Duri ...

(1780–1841) – a Danish adventurer, who was on board one of the ships that established the first settlement in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

in 1801; governor of Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

for two months in 1809; a British spy – held in Newgate for theft before transport to Tasmania in 1825

* William Kidd

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd ( – 23 May 1701), was a Scottish sea captain who was commissioned as a privateer and had experience as a pirate. He was tried and executed in London in 1701 for murder a ...

, known as "Captain Kidd", pirate and privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

– hanged at Execution Dock, Wapping in 1701

* John Law

John Law may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John Law (artist) (born 1958), American artist

* John Law (comics), comic-book character created by Will Eisner

* John Law (film director), Hong Kong film director

* John Law (musician) (born 1961) ...

, economist – sentenced to death at Newgate for murder by duel in 1694

* Thomas Kingsmill (c1715–1749), leader of the notorious Hawkhurst Gang

The Hawkhurst Gang was a notorious criminal organisation involved in smuggling throughout southeast England from 1735 until 1749. One of the more infamous gangs of the early 18th century, they extended their influence from Hawkhurst, their base ...

of smugglers

* Thomas Lloyd, stenographer of the U.S. Congress – convicted of seditious libel while imprisoned for debt, and transferred to Newgate Prison for a three-year prison term (1794–1796)

* James MacLaine

"Captain" James Maclaine (occasionally "Maclean", "MacLean", or "Maclane") (1724 – 3 October 1750) was an Irish man of a respectable presbyterian family who had a brief but notorious career as a mounted highwayman in London with his accompl ...

, known as the "Gentleman Highwayman" – held at Newgate during his 1750 trial for robbery

* Sir Thomas Malory – highwayman, probable author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

'' – at Newgate 1468–1470 after conviction for conspiracy to overthrow the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

* Catherine Murphy, counterfeiter – the last woman to be officially executed by burning in Great Britain, in 1789

* Titus Oates, anti-Catholic conspirator – imprisoned at Newgate (1687–1689) for perjury during the Popish Plot

* William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

, religious scholar, and later the Quaker who founded the colony of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

– held in Newgate during his 1670 trial for preaching before a gathering in the street

* Miles Prance

Miles Prance (''fl.'' 1678) was an English Roman Catholic craftsman who was caught up in and perjured himself during the Popish Plot and the resulting anti-Catholic hysteria in London during the reign of Charles II.

Life

Prance was born on the ...

, silversmith, alleged witness to the murder of Edmund Berry Godfrey – imprisoned during 1679 trial in the Popish Plot

* Cephas Quested, smuggler and leader of The Aldington Gang. Arrested during the Battle of Brookland 11 February 1821 and hung on 4 July 1821

* John Rogers, Bible translator and religious reformer – at Newgate after conviction of heresy in 1554, and burnt at the stake in 1555

* Jack Sheppard, thief and jailbreaker – in the early 1700s, escaped from Newgate several times during imprisonment for theft

* Ikey Solomon

Isaac "Ikey" Solomon (1787? – 1850) was a British criminal who acted as a receiver of stolen property. His well-publicised crimes, escape from arrest, recapture and trial led to his transportation to the Australian penal colony of Van Diemen's ...

, successful and infamous fence of the late 18th and early 19th centuries – lodged at Newgate during 1827 trial for theft and receiving

* Robert Southwell, Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

priest and poet – held at Newgate for treason before being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn in 1595

* Owen Suffolk, con-man

A confidence trick is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using their credulity, naïveté, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibility, and greed. Researchers have def ...

and later Australian bushranger – served time for forgery in 1846 before transport

* Jane Voss

Jane Voss alias Jane Roberts (d. 1684), was an English highwayrobber and thief.Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

She was reputedly born in St Giles-in-the-Fields in London. She engaged in highway robbery with multiple male accomplices, a ...

(alias Jane Roberts), highwaywoman and thief – executed in 1684

* Mary Wade

Mary Wade (17 December 1775 – 17 December 1859) was a British woman and convict who was transported to Australia when she was 13 years old. She was the youngest convict aboard , part of the Second Fleet. Her family grew to include five gener ...

, beggar – sentenced to death at Newgate for theft but then transported, becoming the youngest female convict transported to Australia

* Edward Gibbon Wakefield, British politician, the driving force behind much of the early colonization of South Australia, and later New Zealand – served three years in Newgate for 1826 abduction

Abduction may refer to:

Media

Film and television

* "Abduction" (''The Outer Limits''), a 2001 television episode

* " Abduction" (''Death Note'') a Japanese animation television series

* " Abductions" (''Totally Spies!''), a 2002 episode of an ...

* Joseph Wall, colonial administrator – hanged 1802 for having a British soldier flogged to death

* John Walter Sr., publisher, founder of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' – imprisoned for a year (1789–1790) for libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defi ...

on the Duke of York

* Oscar Wilde, briefly held at Newgate in 1895 before transfer to Pentonville.

* Catherine Wilson

Catherine Wilson (1822 – 20 October 1862) was a British murderer who was hanged for one murder, but was generally thought at the time to have committed six others. She worked as a nurse and poisoned her victims after encouraging them to leav ...

, nurse and suspected serial killer – last woman hanged publicly in London, at Newgate in 1862

Legacy

TheCentral Criminal Court A Central Criminal Court refers to major legal court responsible for trying crimes within a given jurisdiction. Such courts include:

*The name by which the Crown Court is known when it sits in the City of London

*Central Criminal Court of England a ...

– also known as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands – now stands upon the Newgate Prison site.

The original iron gate leading to the gallows was used for decades in an alleyway in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, USA. It is currently housed in that city at Canisius College

Canisius College is a private Jesuit college in Buffalo, New York. It was founded in 1870 by Jesuits from Germany and is named after St. Peter Canisius. Canisius offers more than 100 undergraduate majors and minors, and around 34 master' ...

.

The original door from a prison cell used to house St. Oliver Plunkett in 1681 is on display at St Peter's Church St. Peter's Church, Old St. Peter's Church, or other variations may refer to:

* St. Peter's Basilica in Rome

Australia

* St Peter's, Eastern Hill, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

* St Peters Church, St Peters, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

...

in Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

, Ireland (which also displays his head).

The phrase " sblack as Newgate's knocker" is a Cockney reference to the door knocker on the front of the prison.

In literature

A record of executions conducted at the prison, together with commentary, was published as '' The Newgate Calendar''. The prison appears in a number of works byCharles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

. Novels include '' Little Dorrit'', '' Oliver Twist'', '' A Tale of Two Cities'', '' Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty'' and '' Great Expectations''. Newgate prison was also the subject of an entire essay in his work '' Sketches by Boz''.

In song

The Australian "Convict's Rum Song" mentions Newgate with a line reading: '' 'd... even dance the Newgate Hornpipe If ye'll only gimme Rum!''. The 'Newgate Hornpipe' refers to execution by hanging.''A Dictionary of Slang and Colloquial English'' by John Stephen Farmer (G. Routledge & Sons, Limited, 1921), page 305.Gallery

References

NotesFurther reading

* Babington, Anthony. "Newgate in the Eighteenth Century" '' History Today'' (Sept 1971), Vol. 21 Issue 9, pp 650–657 online. *External links

Newgate prison

Prison History Database: Newgate Prison

Newgate prison

The Diary of Thomas Lloyd kept in Newgate Prison, 1794–1796

{{Coord, 51, 30, 56.49, N, 0, 06, 06.91, W, region:GB_type:landmark, display=title 1188 establishments in England Buildings and structures demolished in 1777 Defunct prisons in London Former buildings and structures in the City of London Demolished buildings and structures in London Debtors' prisons Demolished prisons Buildings and structures demolished in 1904 Windmills in London